Figure 6.1 The Wisconsin General Test Apparatus. The experimenter can retract the tray, re-arrange the objects, place food under some of them, and then present the tray again to the monkey (Harlow, 1949).

The principles elaborated in the preceding chapters permit us to describe and analyze a large fraction of the learned behavior of people and other animals. But were we to terminate our account of behavior with the phenomena of operant conditioning, classical conditioning, stimulus control, and aversive contingencies, we would still be forced to admit that the bulk of complex human behavior had either been left untouched or at best dealt with rather indirectly. The activities that might be classified as complex human behaviors are, of course, extremely diverse, and in this chapter we will examine concept acquisition and modeling, and then turn to verbal behavior itself which seems so intimately associated with many forms of complex human behavior.

For each category of complex human behavior, we will set out to define it carefully in behavioral terms, and examine the extent to which we can relate it to the principles of behavior outlined in earlier chapters. In so doing, we will be using the comparative perspective that is prevalent throughout this book. That is, we will be seeking to identify those behavioral processes that contribute to complex human behavior that are shared with other species. Because behavioral science is a biological science our initial strategy should always be to seek to establish these commonalties. We will also extend this strategy to verbal behavior, which has often been seen by philosophers, linguists, and psychologists of other orientations, as not being susceptible to this approach.

To "acquire a concept" or "form a concept" sounds like an abstract mental process, with no obvious behavioral connotations. Consideration of what it means to "have a concept", however, suggests that concept acquisition is closely related to the behavioral process of discrimination.

If a child has the concept of "school", he or she will apply this name to educational establishments, but not to other large public buildings, as he or she may have done when younger. We may say that the response "school" is under the discriminative control of a particular stimulus class. This class might be defined as those buildings having features common to schools and not found in other buildings, or it might be a class established through the process of stimulus equivalence class formation described in Chapter 4. In either case, an experimental investigation would be necessary to find out which features are important in the control of this child's behavior. It is an important general point that each person's stimulus classes, or concepts, are their own. That is, two people might both use the phrase "new car", for example, but it may mean something slightly different to each of them. This difference will have come about through the different experiences of the two individuals.

We begin with a consideration of a simple animal discrimination learning paradigm, which shares certain important properties with human concept acquisition. This will enable us to identify the term concept with certain precise features of behavior.

One class of discriminations involves two situations and two responses (this is slightly more complicated than the examples used in Chapter 4), and has been studied using the Wisconsin General Test Apparatus (WGTA), shown in Figure 6.1. Seated in front of the WGTA, a monkey or other primate, may be presented with several objects on a movable tray, one object concealing a peanut in a well beneath it. Suppose two objects to be in use, a solid wooden cross and a solid wooden U-shaped object. The peanut is always to be found under the cross figure, whether the latter appears on the left or on the right. The two possible contingencies may be diagrammed as

S+u: RL → S+ and Su+: RR → S+

where S+u means that the cross is on the left, Su+ means that the objects are reversed, RL means that the monkey lifts the object on the left, and RR means that the monkey lifts the object on the right. Any "incorrect" responses have no consequences except the removal of the tray, while "correct" responses (those specified above) produce the peanut (S+). A learning trial consists of presentation of one of the two possible contingencies. Either a correct or an incorrect response terminates the trial, and the next trial follows after a short intertrial interval.

Over a number of such trials, a discrimination will develop favoring reaching for the "cross". Since this process is a gradual one, tens to hundreds of trials, depending on species and individual differences, may be necessary to reach an asymptotic value of near or at 100 per cent "correct" responses.

Figure 6.1 The Wisconsin General Test Apparatus. The experimenter can retract the tray, re-arrange the objects, place food under some of them, and then present the tray again to the monkey (Harlow, 1949).

Each single set of these contingencies is called a discrimination problem. Suppose, once the discrimination process has reached its asymptote, or steady maximum value, we present a new set of contingencies, differing from the old contingencies only in the objects used as the two stimuli, for example, a solid wooden sphere and an inverted wooden cone. This time, the discrimination process will be slightly more rapid. We can then continue to present new problems, one after the other, using different objects, and the discrimination processes will become appreciably more rapid: perhaps less than a half-dozen trials are necessary for errorless performance by the time 100 discriminations have been learned. Eventually, after several hundred problems, the monkey is able to solve any new problem of this sort immediately. If, by chance, it chooses the correct object on Trial 1, it thereafter continues to choose the correct object. If, by chance, it chooses the wrong object on Trial 1, it reverses its response pattern immediately and chooses the correct object from Trial 2 on. In both cases, the monkey's performance is nearly always perfect by Trial 2. In effect, presentation of a long series of similar problems has eradicated the gradual discrimination process. We are left with an animal that solves new discriminations immediately.

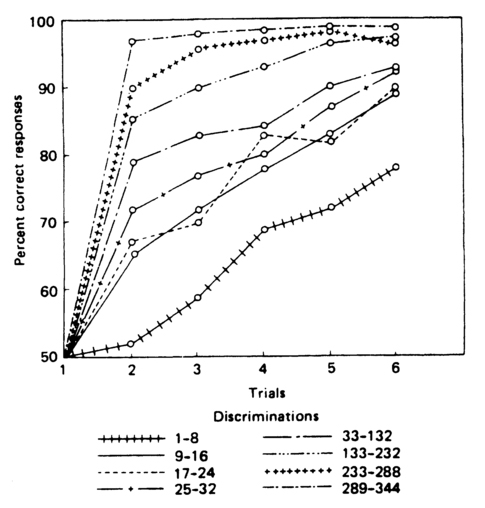

Figure 6.2 shows results of this learning set (L-set) procedure obtained from a typical experiment with rhesus monkeys. Each curve is the average of a number of discrimination processes resulting from different discrimination problems, shown for Trials 1 to 6 only. "Discrimination process 1 to 8" is gradual, and it is clear that its maximum value would occur well beyond the 6 acquisition trials shown. The average process for problems 9 to 16 is less gradual; the curve is steeper and will reach its asymptote more quickly. Subsequent processes are still steeper, until, after 232 problems, there is no "process" as such. There is only the result: on Trial 2, the monkey is nearly always correct. Performance on Trial 2 can be used to track the development of this skill, known as a learning set (L-set).

Figure 6.2 Changes in rate of acquisition of acquisition of discrimination processes. The curves are average scores of eight monkeys (after Harlow, 1949). Details are given in the text.

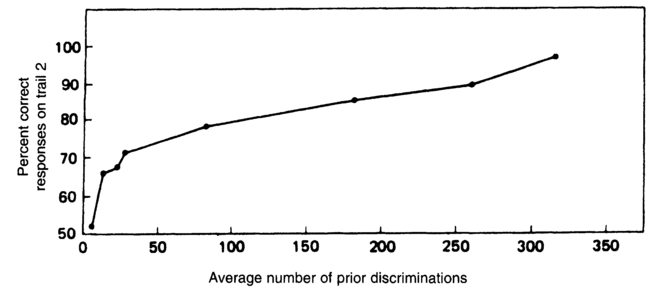

Figure 6.3 shows the performance level on Trial 2 as a function of the number of problems previously presented. The figure is, then, a convenient description of the L-set acquisition process, and an important feature of the process shown is its gradual and continuous character: the ability to solve a discrimination problem in one trial is itself acquired by a gradual process.

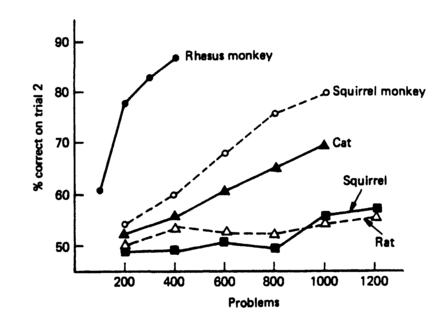

L-set performance varies with the species tested. Children tested in L-set procedures typically surpass chimpanzees and monkeys in overall performance, but they, too, exhibit a continuous L-set acquisition process. Primates lower on the phylogenetic scale than rhesus monkeys, such as squirrel monkeys and marmosets, show a more gradual L-set acquisition process than Figure 6.3 depicts. Even after 1,000 or more problems, the asymptote of their L-set process is significantly lower than perfect L-set performance. Other animals, like rats and cats, show some steepening in successive discrimination processes, but they never reach sophisticated L-set results within the limits of the experiments that have been performed. A summary from five species is shown in Figure 6.4.

These data suggest that "true" L-sets are a privileged ability of primates. Such a conclusion would have to be treated with great caution, in view of the many methodological difficulties in establishing comparable problems for different species, but has in any case turned out to be wrong. Herman and Arbeit (1973) have shown that a bottle-nosed dolphin is capable of performing from 86 to 100 per cent correct on Trial 2 of each problem of an auditory L-set task. The experimental study of learning continues both to erode the number of behaviors attributable only to humans and to "upgrade" many species not previously suspected of "higher" learning abilities.

Figure 6.3 Development of a learning set. Data are derived from Figure 6.2, based on performance on Trial 2.

Figure 6.4 Performance of five species on a series of visual discrimination problems (from Mackintosh, 1974; after Warren, 1965).

We have avoided using the term "concept" in the preceding discussions, but it seems natural to wonder whether an organism possessing an L-set for the larger of two objects, or for the green one of two objects might reasonably be said to exhibit the concept "larger of two", or "green one of two". Perhaps the "concept" acquired in the example with the WGTA is "the object of the two presented which had the peanut under it on the previous trial". Such behavioral control in humans is often the basis upon which we assign the word "concept". For instance, we agree that a child has the concept of ownership when he or she can discriminate his or her own possessions from those of anyone else. We say that a child has the concept of a noun phrase when he or she can pick out the noun phrases from unfamiliar sentences. Similarly, we credit the child with the concept of equality of number when he or she can identify equal quantities in unfamiliar settings, as when he or she can match the number of beads in one jar to the number of apples on a table. However, we require a more rigorous definition of a "concept" if we wish to examine in detail the relation between L-sets and concepts.

Put more formally, an organism is said to exhibit a concept when it can identify any member of a set of related situations. Additionally, the organism can acquire that ability via an explicit reinforcement history, or instructions relying on a previous reinforcement history, in the presence of a subset of the situations.

This definition enables us to link the L-set paradigm to concept formation. The L-set procedure is a systematic way of ordering a reinforcement history that leads to conceptual behavior. Though the monkeys do not speak, the behavior they acquire from L-set procedures seems analogous to what humans in concept-formation experiments do, using verbal responses. The word "concept" denotes the behavioral fact that a given response is under the control of a class of related SD's. An interesting corollary of this definition is that it does not separate a concept from a discrimination, which is the behavioral fact that an SD has come to control an operant response. Our word usage in a particular case will be determined merely by the broadness of the class of controlling SD's. If the class of SD's seems relatively narrow, we call the behavior a discrimination, if it seems relatively wide or broad, we are more likely to call the behavior a concept. We may also use the term concept where it is clear that the stimulus class that controls the behavior has been established through a process of stimulus equivalence class formation and contains elements that are physically unrelated. We will further discuss this category in the next section.

In the previous sections, we have claimed that when the behavior of organisms comes under the discriminative control of the members of a broad class of SD's, these organisms are demonstrating conceptual behavior. In the concepts discussed, the controlling SD classes may be described as a set of stimuli bound together by a common relationship of spatial arrangement or structure. In other concepts, such as "bigger than", "comes from", "to the right of", "is a member of", "leads to", and "threeness", the common relationships binding all the elements of the class are not spatial structure, but other types of relationships that are named by the verbal responses they produce. Thus, "bigger than" is a verbal response that names the relationship shared by the members of the controlling SD class.

While relational concepts are very common, behavior is also frequently observed to come under the control of broad classes of stimuli whose members seem to lack common relationships. An obvious physical stimulus relationship, for instance, is absent in the SD's for "food". A carrot, a pea, a leaf of spinach, and a glass of milk appear as extremely diverse objects. From its visual characteristics alone, a pea is more like a marble than it is like a leaf; a carrot is more like a stick than it is like a glass of milk. Evidently, dissimilarity in the members of a broad SD class is no deterrent to their ability to control a similar response. Such stimulus classes are known as disjunctive concepts. The members of the SD class "food" are either carrots, or peas, or spinach, or milk, ... . The response is under the control of a broad class of SD's, and therefore, meets one of the important criteria of conceptual behavior; nevertheless, the lack of a single common relationship, a thread linking all the members of the class, prevents the generalization to new members that is typical of other concepts. These disjunctive concepts are very important. That is, there are many stimulus classes where all the elements control the same response but where the members of the class are very physically diverse, such as the concepts "my friends", or "famous writers".

The key point is that an individual who has such a concept has learnt to treat the elements as equivalent. We have already described this process in Chapter 4 as stimulus equivalence class formation. Verbally-competent humans appear to be different from other animals in that they can develop large classes of functionally-equivalent stimuli, even though those stimuli, the elements of the class, are physically dissimilar from each other. Once a new member is added to the class it is treated the same as the others. Thus, if a person acquires a new friend, he or she may then invite them to a party along with other friends. Similarly, if a person learns that Thackeray is a famous writer he or she may then buy Thackeray's books when they appear in the store without further encouragement. In each case, the new member of the stimulus class is being treated as if it is the same as other class elements that have been encountered previously and reinforced under certain circumstances.

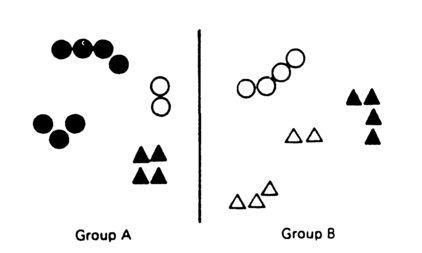

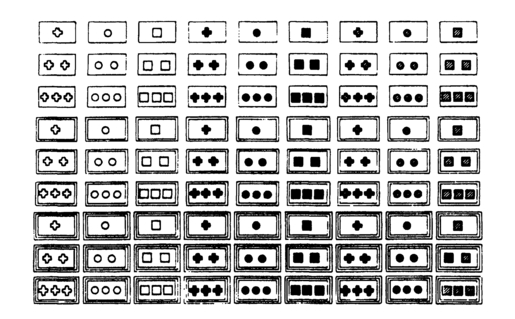

Formally, in an m-out-of-n polymorphous rule, there are n relevant conditions of which m must be satisfied. An example is given in Figure 6.5 from a study by Dennis, Hampton, and Lea (1973) who used a card-sorting task to examine polymorphous concepts. The rule here is: "A member of Class A possesses at least two of the properties symmetric, black, and circular (all other stimuli are members of Class B)." While the card-sorting task is highly artificial, it is arguable that most of our "real world" or natural concepts are of this type. For example, a person will have many features common to people in general, but no one feature is necessary.

Figure 6.5 Patterns of geometric symbols grouped according to a two-out-of-three polymorphous rule (Dennis, Hampton, & Lea, 1973).

In the first experiment of Dennis et al. (1973), college students were asked to sort packs of cards showing either rows of shapes (as in Figure 6.5), typewritten letters, or random shapes into two piles (A and B). After each response, the experimenter told them whether their allocation of a card to a pile was "right" or "wrong". On different trials, the participants were required to sort the cards by a conjunctive rule (for example, "A's are black AND composed of circles"), or disjunctive rule (for example, "A's are black OR composed of triangles"), or a polymorphous rule such as the one previously described. They sorted a pack of 48 cards and the response measured was the number of cards sorted before the last error, where an error is putting a card in the wrong pile. Dennis et al. (1973) found that the median number of cards sorted was 9, 28, and 40 for the conjunctive, disjunctive, and polymorphous rules, respectively. This shows that the polymorphous concept was the most difficult to acquire, then the disjunctive, then the conjunctive.

In a second experiment, each participant was given four examples in each category (A and B) and asked to state the rule. Again, each participant was tested with cards divided according to a conjunctive, disjunctive, and polymorphous rule. They were given a maximum of 10 minutes to solve the problems. The median solution times were 34 seconds, 2 minutes 35 seconds, and 10 minutes, respectively. This means that typically the participants failed to state the polymorphous rule within 10 minutes, although the disjunctive rule was produced fairly quickly and the conjunctive rule very quickly. Comparison between their first and second experiments suggests that polymorphous conceptual behavior in response to reinforcement contingencies is acquired only slightly more slowly than conjunctive and disjunctive conceptual behavior, but polymorphous rules take a great deal longer to acquire than the other types. This points out that contingency-shaped behavior does not depend on prior acquisition of the corresponding verbal behavior, or rules.

This view is supported by experiments with pigeons. Using food reinforcement for key pecking, pigeons have been trained to successfully discriminate between color slides with and without people in them, although the people were at all sorts of positions, angles, distances, and so forth (Herrnstein & Loveland, 1964). "Person" is clearly a polymorphous concept as previously defined. Furthermore, Lea and Harrison (1978) trained pigeons in a similar procedure to discriminate on the basis of a 2-out-of-3 polymorphous concept, similar to the ones used by Dennis et al. (1973). If pigeons can acquire polymorphous concepts, but humans have great difficulty in stating polymorphous rules, we can only conclude that acquisition of the verbal rule is not a necessary condition for solving this sort of problem. Further research has provided extensive evidence of pigeons' ability to discriminate both natural concepts, such as people, fish, trees, etc., and artificial concepts, such as Lea and Harrison's polymorphous concepts (for example, Bhatt, Wasserman, Reynolds, & Krauss, 1988).

The studies of conceptual behavior discussed in this chapter illustrate both the continuity between psychological processes in humans and other species, and also the differences. While many species need, and can be shown through experiments to have, the capacity to make subtle discriminations and to identify natural concepts, human beings show greater facility and have the additional capacity to form stimulus equivalence classes. This in turn is related to our use of verbal behavior, which will be further discussed later in this chapter.

A standard combination lock presents a problem, which can only be solved by trial and error. Thus a lock with 50 numbers, which opens when the correct sequence of three numbers is dialed, will require an average of 503/2 or 62,500 sequences to be tried before it will open. Supposing each sequence took 6 seconds to complete, this would take about four days and thus makes such a lock an effective form of protection. The statement "try every possible combination" is a rule guaranteeing its eventual (but not rapid) solution. In other situations we may use search strategies, or "rules of thumb", designed to save time in reaching a solution. If an individual can solve problems of a particular type, he or she is said to know the rules for their solution.

"Knowing the rules" is clearly related to "having the concept". Correctly identifying dogs, is like being able to state a rule specifying what will count as a dog. However, there are important differences. First, accurate use of concepts does not imply that the user will be able to produce a verbal rule. Second, once a rule has been stated, it may exert control over behavior directly. This is an interesting phenomenon, because from a behavior analysis perspective "stating a verbal rule" is itself a type of behavior, albeit verbal behavior. We are here noting a very important and complex aspect of human psychology: our accounts of some psychological processes involve behavior-behavior relationships, as well as the environment-behavior relationships which have been frequently encountered in this volume. Rule-governed behavior, discussed further in Section 6.8, is the general name for those occasions where verbal behavior, in the form of a rule, is acquired either through verbal instruction or through direct experience of some reinforcement contingencies, and then determines other behavior.

If a three-number sequence is required to open a combination lock, and the sequence is always such that the third number is twice the second number, which is the same as the first, then once this rule is acquired, it will be used. The rule provides for very efficient problem solution (and thus reinforcement of the appropriate behavior). However, as we saw in the previous section, learning the rule is not the same as responding to the reinforcement contingencies. There are many types of human behavior that are influenced by reinforcement contingencies without the individual knowing rules or even thinking them relevant. The baseball pitcher pitches with great accuracy without being able to articulate the rules governing his or her own movements or the flight of the ball in the air.

With human participants, it is possible to carry out concept formation experiments, and concurrently ask them to verbalize the rule that defines the concept. They are asked to specify which features of a stimulus determine its allocation to a particular category. These procedures are called concept identification. Bruner, Goodnow, and Austin (1956) presented human participants in experiments with the 81 cards shown in Figure 6.6. These cards varied in four ways: (1) the number of figures (1, 2, or 3), (2) the color of the figures (red, green, or black), (3) the shape of the figures (cross, circle, or square), and (4) the number of borders (1, 2, or 3). The participants were first shown a given card (for example, the one with three red circles and two borders, which can be written as "3R-o-2b") and told that this was a positive instance of a concept that they were to identify. The participants were then advised that they could choose additional cards from the 80 remaining to obtain more information. After each choice, they were advised whether the particular card they chose was or was not an instance of the concept When the task consisted of identifying conjunctive concepts (red circles, two green figures and so on), the majority of participants adopted a strategy which consisted of choosing cards that varied in one, and only one, dimension from the known initial positive card. In this way, each selection eliminated one or more concepts. Bruner, Goodnow, and Austin were able to show that a number of variables, such as whether the concept was conjunctive or disjunctive, the manner in which the 81 cards were displayed, and the number of examples the participants were permitted to choose, affected the type of systematic strategy employed. In such a situation, the participant is prompted to devise rules which are in turn highly effective strategies for arriving at correct responses.

Figure 6.6 A set of cards used to study concept identification. The forms vary in number, shape, color, and number of borders (Bruner, Goodnow, & Austin, 1956).

The experimental analysis of behavior has been mostly concerned with the factors that govern the performance of a behavior, and less concerned about how that behavior is acquired. For this reason, operants selected for study have usually been simple acts which can be completed in a very short space of time (lever pressing, key pecking, button pressing, and so on). Similarly, although it is acknowledged that classical conditioning can simultaneously produce diverse effects on behavior, investigators have normally looked in detail at a single, relatively simple, aspect of behavior (salivation, eyeblinks, heart-rate, and so forth). Thus, neither operant nor classical-conditioning techniques are oriented to the analysis of the acquisition of complex behavioral sequences. However, it is a compelling fact that humans readily acquire such sequences, and often do so very rapidly. Moreover, in applied behavior analysis, acquisition of behavior sequences is often the primary objective. In Chapter 9, we will discuss a range of techniques for enhancing such acquisition. These involve combinations of techniques that have already been introduced, along with modeling, which will be introduced here.

Many everyday examples of acquisition of complex behavior sequences seem to depend on observation. For example, the new factory worker may be shown how the machine works by the supervisor, and then he or she can operate it himself or herself immediately with reasonable efficiency. His or her subsequent improvement towards being a skilled operator depends on feedback (reinforcement) from the machine and from co-workers, but the rapid initial acquisition is hard to explain by operant principles. We might crudely conceptualise it thus:

While this might suffice to explain why "copying supervisor's behavior" is performed, it does not provide a mechanism for its acquisition. How does the worker manage to execute a long and complex behavior sequence that he or she has not produced previously or been reinforced for?

The only operant principle that might provide an explanation is chaining, which will be one of the techniques discussed in detail in Chapter 9. Behavior chains are sequences that are reinforced when completed. They can be long and complex, but they are established through a relatively lengthy piecing-together process of shaping — also discussed at length in Chapter 9 — and this involves explicit reinforcement. In our present example, however, there is only a single demonstration (trial) and no explicit reinforcement for either worker or supervisor.

If an observer acquires a new response pattern or behavior sequence by observation of another individual, this is an instance of modeling. There are three types of modeling influence. The first, and most striking, is the one we have described. This can be called the response acquisition effect of modeling. Observation of a model (another person) may also lead to the inhibition or facilitation of already learned behavior. For example, observing someone else making jokes about a taboo subject and gaining approval may lead to the observer telling similar jokes. We will call this the response modulation effect. The third modeling effect occurs when the behavior of others functions as a discriminative stimulus for the same type of behavior by the observer. If the person walking along the street in front of you suddenly stops and gazes up into the sky, it is very likely that you will do the same when you reach that point in the street. This is the response facilitation effect. It differs from the response modulation effect in that the consequences of the model's behavior are important in response modulation, but not in response facilitation. If your companion makes a joke about religion which is followed by an embarrassed silence, this will tend to inhibit similar behavior on your part. Response facilitation, on the other hand, can occur without the observer seeing the consequences of the model's behavior. The response facilitation effect differs from the response acquisition effect because response facilitation does not involve any "new" behavior. Rather, the observer produces behavior already in his or her repertoire. In both cases, however the model's behavior functions as a discriminative stimulus for the same behavior by the observer.

The response facilitation effect is well known to ethologists (scientists concerned with the observation of animal behavior in natural settings). The coordinated behavior of flocks or herds of animals is controlled in this fashion. Psychologists, on the other hand, have been primarily concerned with the response acquisition and response modulation effects. These differ in that the former is an effect on learning (the acquisition of behavior or change in the behavioral repertoire), while the latter is an effect on performance (the probability of the behavior occurring in a particular situation).

Bandura and associates carried out a classic series of studies showing the powerful effects on children of short periods of observing adults or children modeling specific behaviors. In a typical study (Bandura, 1965), children (aged 42 to 71 months) watched film of an adult who produced several novel, physical and verbal aggressive behaviors. The film lasted 5 minutes and involved an adult approaching an adult-sized plastic doll and ordering it out of the way. Then the model (the adult) laid the doll on its side, sat on it, and punched it on the nose. This was followed by hitting it on the head with a mallet and then kicking it round the room. Finally, the model threw rubber balls at the doll. Each act of physical aggression was accompanied by a particular verbal aggressive response. Following this performance, the children observing the film saw one of three closing scenes. Either another adult appeared with candies and soft drinks and congratulated the model, giving the model food and drink (model-rewarded group), or the second adult came in and reprimanded the model, while spanking the model with a rolled-up magazine (model-punished group). For a third group of children, the film ended before the second adult arrived (no-consequences group). Immediately after watching the film, each child was taken to a room containing a similar large doll, a mallet, balls, and a number of other toys not seen in the film. The child spent 10 minutes in this room, where they could be observed through a one-way mirror. The experimenter then entered, carrying soft drinks and pictures. These were offered to the child as rewards if he or she could imitate what the model had done in the film. Each modeled behavior that the child produced was reinforced with a drink or a picture.

The results from both parts of the experiment are shown separately for boys and girls in Figure 6.7. There were 11 participants in each of the six groups. The most notable feature of the data is the generally high level of modeling behavior. After watching a short film, a number of conditions produced mean levels of between 3 and 4 different modeled behaviors out of a possible maximum of 8 (4 physical acts and 4 verbal behaviors). Apart from this, the sex of the children, the consequences for the model, and the consequences for the children all influenced behavior. Figure 6.7 shows that in the first observation period, when no reinforcement was provided, the boys reproduced more of the model's aggressive acts than the girls. In the second period, however, when modeling was reinforced, all groups considerably increased modeling behavior and the differences between the sexes were largely eliminated. These two phases demonstrate: (1) that some modeling occurs without reinforcement for the participants (this is the response acquisition effect); (2) some modeled responses are acquired that may not be performed unless explicitly reinforced; and (3) the sex difference in aggressive behavior diminishes when aggression is reinforced. In the first observation period, the amount of modeled behavior was also influenced by the observed consequences of the behavior for the model. If the model had been seen to be punished for the aggressive behavior, the children showed less aggression. The effect was particularly dramatic for the girls in the model-punished group. They modeled an average of less than 0.5 aggressive acts in the first period, but increased this to more than 3.0 when subsequently reinforced for aggressive acts. This exemplifies a powerful response modulation effect: performance of aggressive behavior was jointly influenced by the observed consequences for the model and the available consequences for the participant.

Figure 6.7 Average number of aggressive acts modeled by children as a function of consequences for the model, sex of child, and whether the child was reinforced for modeling (Bandura, 1965).

In Bandura's (1965) study, observation of the adult model for a short period of time was a sufficient condition for the children to imitate some of the model's behavior without reinforcement or explicit instructions. This is a remarkable finding and suggests that modeling may be responsible for the acquisition of many social and complex behaviors. After all, we spend a great deal of time observing the behavior of others. However, we obviously do not acquire all the behavior we observe, and some models must be more likely to be imitated than others. It turns out that models with demonstrated high competence, who are experts or celebrities, are more likely to be imitated. The age, sex, social power, and ethnic status of the model also influence its effectiveness (Bandura, 1969)

Bandura (1969) describes modeling as "no-trial learning" because response acquisition can occur without the observer being reinforced. As modeling effects cannot be described as classical conditioning either, Bandura concludes that there is a modeling process that can be distinguished from both operant and classical conditioning processes. However, it is possible that modeling is maintained by conditioned reinforcement. We all have a history of being reinforced for behavioral similarity, or matching the behavior of a model. During language acquisition by a young child, for example, parents often spend long periods of time coaxing the child to repeat a particular word or phrase. When the child finally produces the appropriate utterance, this behavioral similarity is immediately reinforced.

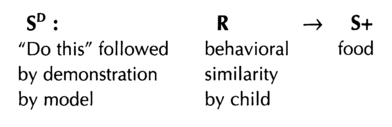

As behavioral similarity is often paired with reinforcement in this way, it could become a conditioned reinforcer. If behavioral similarity does have conditioned reinforcing properties, this might explain how modeling behavior can occur in experimental and clinical studies, even though it is not apparently reinforced. The paradigm would be:

where the last term, S+, is a conditioned reinforcer. Behavioral similarity would only acquire and retain conditioned reinforcing properties if it was explicitly reinforced in a variety of situations. Nonreinforced modeling in the test situation can then be described as generalized imitation, because modeling behavior is generalizing from reinforced to nonreinforced situations. Gladstone and Cooley (1975) were able to demonstrate conditioned reinforcing effects of behavioral similarity. Children were given the opportunity to model a behavior sequence (that is, act as models) and then operate a bell, a horn, or a clicker. If the appropriate one of these responses was made, the experimenter (acting as the observer) immediately imitated the behavior the child had modeled. If behavioral similarity has reinforcing properties, the child-model should select the response that resulted in imitation by the experimenter-observer, and this did indeed happen. This study demonstrates reinforcing effects of behavioral similarity, and raises the possibility that these effects are involved in all modeling situations.

Even if conditioned reinforcement contributed to modeling effects, however, we still have to explain how behavioral similarity is achieved by the observer. As we pointed out earlier, the sudden production of integrated behavior sequences is one of the most striking features of response acquisition through modeling, and this cannot be accounted for by operant reinforcement principles alone. Operant conditioning principles, as outlined so far, are concerned mainly with processes of selection, because a reinforcement contingency operates to increase or decrease the frequency of an existing category of behavior relative to other categories of behavior. However, as we have noted from time to time, we need also to investigate those processes of behavioral variation that provide the "raw material" on which contingencies operate. In Chapters 2 and 3 we discussed extinction and shaping which are examples of these, and this aspect of modeling may be another source of behavioral variation.

Given that operant reinforcement and modeling can both modify the behavioral repertoire, the joint operation of both should be a highly effective method of altering behavior, and so it has proved. It is particularly suitable for conditions of behavioral deficit. A behavioral deficit means that an individual simply lacks a class of behavior common in other individuals. We will present much information on the use of modeling with reinforcement to resolve human behavioral problems in Chapter 9; the discussion here is to address theoretical issues.

Behavioral deficits have a peculiar influence on the relationship between the individual's behavior and the contingencies of reinforcement provided by the society in which he or she lives. Normally, the incidence of a class of behavior, for example, talking, is continuously modified by the social environment. Someone who never speaks, however, fails to make contact with these contingencies. Their situation is quite different from that of a low-frequency talker, whose talking may have been suppressed by verbal punishment, or may subsequently increase as a result of reinforcement. The non-talker will be neither reinforced nor punished.

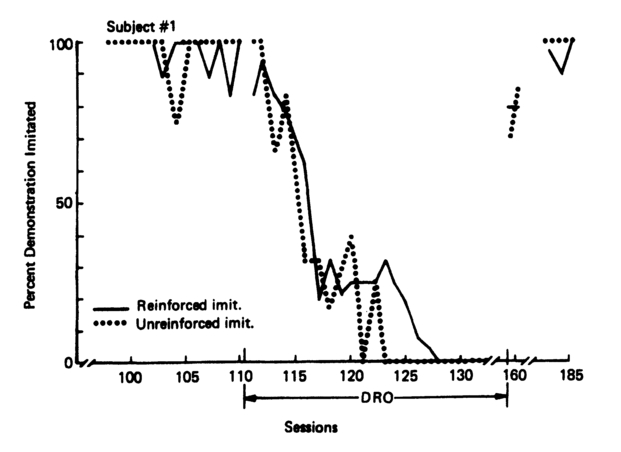

Behavioral deficits, then, represent a severe type of behavior problem. Baer, Peterson, and Sherman (1967) attempted to alleviate this problem in three children with learning difficulties (aged 9 to 12 years) with very large deficits that included failure to imitate any behavior. The children were taught a series of discriminated operants of this form:

As no imitative behavior occurred initially, shaping was used. This involved assisting the participant, physically, to make the appropriate sequence of actions, and then delivering food reinforcement. Sessions were always conducted at meal times, and the amount of assistance was gradually reduced.

After initial training, imitation of some of the model's demonstrated responses were never reinforced and these responses thus formed an SΔ class. Following SD – SΔ training, all imitation was extinguished, and reinforcement was now delivered if no imitation occurred for a specified period after the model's demonstration. (This is a DRO schedule, the differential reinforcement of other behavior than the previously reinforced response.) The results for a representative participant are shown in Figure 6.8. Reinforcement maintained a high level of SD responding, but also a high level of SΔ responding. When the DRO schedule was introduced, both rates declined gradually to zero. Responding to SD and SΔ recovered when reinforcement for SD was reintroduced.

Figure 6.8 Reinforced imitative and nonreinforced imitative responding by a single child during a sequence of different reinforcement conditions (Baer, Peterson, & Sherman, 1967). Details are given in text.

Baer, Peterson, and Sherman's procedure had powerful effects: responding to SD was maintained at a high level by reinforcement and suppressed by the DRO contingency. Modeling was undoubtedly critical, as well, because reinforcement alone could not account for the high levels of responding shown by these participants. Remember that prior to the experiment, they had a very limited behavioral repertoire. The procedure also generated a high level of SD responding, and extended SD – SΔ training failed to suppress responding to SΔ.

The SΔ responding represents a "failure to discriminate" in operant terminology, which might have resulted from the discrimination being difficult because both SD and SΔ classes were demonstrated by the same model, Bandura and Barab (1973) replicated this result with a single model, but found that SΔ responding was suppressed if there was one model for SD and a different model for SΔ. The fact of "discrimination failure" when a single model is used is important, because it is a further demonstration of the response acquisition effect; under appropriate conditions observers will imitate the behavior of a model, even when there is no explicit reinforcement for imitation.

There has been much debate as to the role of reinforcement and modeling in language acquisition by children; it has even been claimed that these strategies of "training by parents", which all parents engage in at a high level, are not very relevant to children's acquisition of these crucial verbal behavioral skills (Chomsky, 1959). However, Hailiday and Leslie (1986) provided extensive evidence from a longitudinal study of mother-child interaction that there are strong, but complex, relationships between modeling of verbal behavior by mothers and the development of verbal competence in children. For example, from early on (perhaps when the child is 18 months old), the child imitates labels (names given to objects by the mother), and the mother may then selectively imitate the child's utterance by expanding it into a sentence. After weeks or months where this pattern of interaction is typical, the child develops the capacity to produce complete descriptive statements (we will see in the next section that these are called tacts). As throughout this developmental sequence the mother will be engaging in many other behaviors designed to interact with the child (praising, smiling, maintaining eye contact etc.), there is every reason to believe that modeling and reinforcement are key processes in this, as in other, aspects of the child's development.

Chomsky's (1959) scepticism about a behavioral analysis approach to language was expressed in a review of B.F. Skinner's (1957) book, Verbal behavior. In that volume, Skinner set out a general approach that was so radical that it took several decades before the scientific community was able to take it seriously, and only recently has research from this perspective begun to gain momentum.

We will only mention some of Skinner's key concepts here. The one that linguists and others have found most surprising is that he provides a functional, and not a structural, account of language. Talking is the most obvious and important type of verbal behavior and it should be seen as the emission of various types of operants which have different functions. For example, a person might emit a mand (this term is derived from "demand") which is reinforced by the removal of a cold draught from a door. That is its function, its form might be to say "Shut the door!", or "It is draughty in here", or even to gesture at the person standing nearest the door that they should close it. Skinner saw this as strictly analogous to the various response topographies that might occur when a rat presses a lever: a paw, the nose or even the tail might be used, but these members of the operant response class all have the common effect on the environment of depressing the lever. Another type of verbal operant is the tact (a descriptive act) where a person might say "What a beautiful day", or "It has turned out nice again", or the person may simply smile with pleasure as they emerge from a building into the sunshine. Sources of reinforcement for this type are not specified by the operant itself, as they are with mands, but usually involve eliciting social approval or conversation from other people.

Dialogue or conversation is crucial to Skinner's general conception of verbal behavior, which he actually defined as behavior reinforced by the behavior of other people. Key concepts here are the speaker and the listener, who are both part of a verbal community. In a normal conversation, two people repeatedly swap the roles of speaker and listener, or "take turns" and a hypothetical example is given in Figure 6.9. As conversation progresses, an utterance (an element of verbal behavior) by one person may act as the discriminative stimulus for the next utterance by the other person, which may in turn act both as a reinforcer for the previous utterance and a discriminative stimulus for the next utterance by the first person. This analysis is complex, but it is entirely consistent with the treatment of other behavioral processes within behavioral analysis in that the function of a feature of behavior or of the environment is not fixed, but depends on the context in which it occurs.

Verbal behavior takes place within a verbal community. Being members of a verbal community simply means being part of a group of people who routinely talk to each and reinforce each others' verbal behavior. Most of us are extremely sensitive to how our verbal behavior is reacted to by the verbal community: our enjoyment of many social occasions, for example, is critically dependent on the occurrence of "good" conversation. The social practice of shunning, or "being sent to Coventry", where at school or work no-one speaks or replies to the victim, is rightly seen as a severe and cruel punishment.

What is the relationship between verbal behavior and language? Baum (1994) suggests that while verbal behavior is actual human activity (and thus an appropriate subject matter for psychology), language is an abstraction: "The English language, as set of words and grammatical rules for combining them, is a rough description of verbal behavior. It summarizes the way a lot of people talk. It is rough because people often use poor English. Neither the explanations in a dictionary nor the rules in a book of grammar exactly coincide with the utterances of English speakers." (p. 111).

Throughout, we have said that processes of both variation and selection are essential for a complete account of behavior. In the case of verbal behavior, we have outlined some of the important selection processes, but

Figure 6.9 The behavior analytic account of dialog is like a tennis match with each person taking turns as speaker and listener. In this example, Fred and Barney are discussing a tennis match. Responses (verbal utterances) are in boxes, and each response acts as a stimulus for the other person. These are labeled as discriminative stimuli (SD's), but they also have reinforcing properties. Note that the first SD for Fred is a visual one. Barney's second response will act as further SD for Fred who is about to say something else.

we have not said very much about "where verbal behavior comes from" (although modeling is clearly an important source), and it is this question, together with the fact that it appears to be a uniquely human activity, that has often preoccupied the attention of psychologists.

Recent work on stimulus equivalence class formation, outlined in Chapter 4, has led Hayes and Hayes (1992) to suggest that this process underpins our verbal skills. Their argument is best understood as applied to verbal labelling, which itself can be seen as a basic aspect of verbal behavior. A key event in their view is bidirectional training. This occurs when a child is encouraged to say a name for an object, and is also reinforced for selecting the object when hearing the name. A simple example will be when the child is reinforced on some occasions for saying "dog" when the family pet appears, and on other occasions for pointing to the same animal when asked "Where is the dog?". This training, which is a conspicuous feature of child rearing, may result in the dog and the spoken word "dog" becoming members of the same stimulus equivalence class. As we saw in Chapter 4, this means that, in a particular context, they are treated as being the same even though they may be physically dissimilar. With our hypothetical child who has undergone bidirectional training, someone may subsequently shout "Dog!" and elicit the same behavior as if a real dog was leaping towards the child. If the child then learns some French, a shout of "Chien!" when heard in Paris may also produce exactly the same behavior.

It is not yet clear whether stimulus equivalence underpins verbal labelling or vice versa, but it is revealing that humans do appear to be normally able to do both, while extensive research has provided only unconvincing evidence of either phenomenon in other species. Ever since the late-nineteenth century origins of modern psychology, clear evidence for differences in learning capacity between species has been sought but not found. However, this recent work does appear to suggest a clear discontinuity between humans and other species, even chimpanzees (Dugdale & Lowe, 1990; see Leslie, 1993, for a discussion of some related issues).

In Section 6.5, we provided a definition of rule-governed behavior as follows: it is the general name for those occasions where verbal behavior, in the form of a rule, is acquired either through verbal instruction or through direct experience of some reinforcement contingencies, and then determines other behavior. We later noted that while "having a concept" and "following a verbal rule" are related they are not the same thing, because animals that do not appear to have verbal abilities, such as pigeons, can show some evidence of conceptual behavior, and humans can solve complex problems even on occasions when they prove unable to verbalize the correct rule.

These complexities can be clarified by distinguishing between following the rule, and stating the rule. Skinner (1969) defined a rule as a verbal discriminative stimulus that points to a contingency, and for any contingency it is possible to state a verbal rule but, as we have seen with various types of examples, observation that behavior consistent with the verbal rule is occurring does not prove that it is rule-governed; it may be contingency-shaped. With verbally-competent humans, these two types of influence on behavior interact in complex ways. A vehicle driver, for example, cannot provide verbal statements about the adjustments he or she makes to the controls of the car in response to changes in the road surface, but he or she will be able to describe what they decided to do once they realized that they had taken the wrong turning.

A further feature of human behavior is that verbal rules, or instructions, exert powerful effects on behavior that may preclude the operation of contingencies that would otherwise be effective. The presentation of a verbal rule may restrict behavioral variation that would otherwise occur and result in certain behavior being reinforced. Many older people in urban areas, for example, have been given messages such as "You will be attacked if you go out at night", or "Your home will be robbed". Under these influences, but without suffering any crime themselves, they may then lead very restricted lives with much time spent barricaded into their homes. Their behavior may or may not be appropriate, depending on the local level of crime, but it has not been shaped directly by the contingencies.

A general feature of human behavior is that it is more influenced by short-term rather than long-term consequences or contingencies. Many everyday phenomena fit in with this "rule of thumb": we eat sweets (followed by short-term positive consequences) and fail to clean our teeth adequately (avoiding short-term negative consequences) and thus incur the long-term negative consequences of tooth decay and aversive dental treatment, we stay up late having a good time at the party and are unable to complete our work requirements the following day, and so on. Our tendency to follow rules, rather than allowing contingencies to shape our behavior can be seen as a further instance. Rule following is generally itself followed by immediate positive social consequences, while the contingency pointed by the rule may be very far off. An example of the two contingencies, the "real" contingency and the contingency involving following the corresponding rule, is shown in Figure 6.10. Although it may not always be possible to identify reinforcing consequences for a particular instance of rule following, we also engage in a great many social practices that offer generalized support for rule-following behavior. These range from children's games that reward rule following per se, to using negative labels (such as "psychopath") for adults who fail to obey rules.

Figure 6.10 An example of rule following. The response receives short-term social reinforcement, and also results in long-term benefit for the child.

This chapter examines a number of types of complex behavior, using the same strategy of relating human behavior to that of other species, and seeking to use the minimum number of behavioral processes, that characterizes the previous five chapters.

Concept formation is a form of discrimination learning, and studies with a number of species of the development of learning sets provide an illustration of species similarities and differences in complex behavior. If "having a concept" describes the situation where a given response is under the control of a class of discriminative stimuli, then it is clear that stimulus equivalence classes are also examples of concepts. Use of stimulus equivalence classes by verbally-competent humans is an extremely powerful strategy for modifying the behavioral repertoire, because the acquisition of a new function for one member of the class transfers to all the other, physically dissimilar, class members.

Experimental studies have shown that both humans and other species (including pigeons) can establish complex polymorphous concepts, where a positive exemplar has m out of n characteristics. These studies are important because polymorphous concepts are formally very similar to natural concepts (such as trees, or houses), and the studies show that verbal rule-following is not necessary — even in humans — to acquire these concepts.

With human participants, it is possible to carry out concept formation experiments and ask them to verbalize the concepts as they go through the experiment. Rule-formation and rule-following is a highly effective problem solving strategy for humans, and these studies illustrate the tactics adopted.

Modeling is an important behavioral process not discussed in previous chapters, but crucial to the account of acquisition of behavior sequences that will be given in later chapters. It provides a rapid mechanism for acquisition of complex behavior. Experimental studies have shown that robust effects can be obtained on children's behavior, particularly when aggressive behavior is learnt by observing an adult model. It is possible that such modeled behavior is maintained by conditioned reinforcement, but the modeling procedure seems in any case to be an important source of "new" behavior.

A common feature of people with developmental delay or learning difficulties is that they do not imitate behavior readily. However, positive reinforcement of showing behavioral similarity leads to enhanced modeling in such individuals. It is also possible to show that reinforcement of modeling occurs frequently in everyday mother-child interactions.

Recently, researchers in behavior analysis have developed Skinner's (1957) suggestion as to how a functional account of language, or verbal behavior, might proceed. This approach is radically different from the structural approach characteristic of linguistics, but it is readily linked to the functional account of behavior in general that is provided by behavior analysis. One example of this is that the very common human behavior of rule following (such as is specified by the rule "stop at the red light", for example) is maintained by frequent social reinforcement which occurs in close proximity to the rule following behavior, while the contingency described by the rule (such as the possibility of a road crash when vehicles do not stop) often operates only over long periods of time with occasional reinforcement. The rule-following behavior is thus much more useful than direct interaction with the environment.

It is striking that while the conditioning processes reviewed in earlier chapters seem applicable to many species, including humans, both the use of language and ability to form stimulus equivalence classes seem almost exclusively human attributes. It may be that this is where a degree of "discontinuity" between humans and other species is located.