The rise of the Port of New York depended on a large surplus labor force living along the shore. When men heard the cry “along shore men,” they scrambled to the docks, hoping for one day’s wages unloading or loading cargo. A day-labor system persisted on the waterfront, and a surplus of labor meant that the longshoremen had to compete with one another to be chosen for work at the shape-up. A ship’s officer or, later, a dock boss or a criminal racketeer assembled the men at the entrance to the dock and then chose the number of men needed. The others drifted away to wait for another ship. With no guaranteed work or income, the waterfront drew the least-skilled laborers, often immigrants. A Russell Sage Foundation study of longshoremen, published in 1914, identified the shape-up and the uncertainty of steady employment as the source of the hardships the dockworkers confronted each day: “In the hiring we come at once face to face with the most conspicuous characteristic as well as the most far-reaching evil of the work—its irregularity. . . . Longshoremen have no way of knowing exactly when a ship will dock. Their only surety of being on hand for the hiring is to hang about, sometimes for hours until the ship arrives. . . . Nor is there any guarantee that the work will be permanent when obtained. . . . The stability of income necessary to maintain any settled standard of living whatever, does not exist.”1 The flood of immigrants coming to New York for over two centuries ensured a glut of labor in the port, available to be exploited. Desperate men who were willing to endure the uncertainty of the shape-up could always be found.

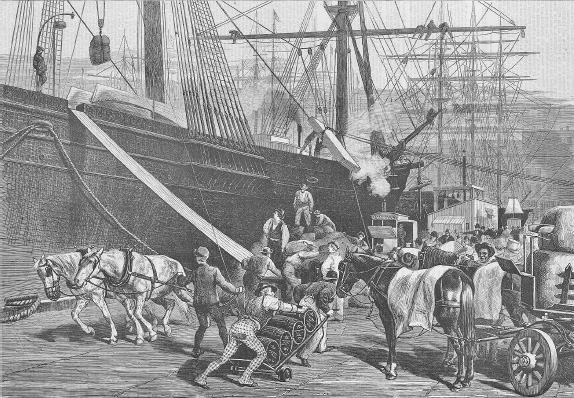

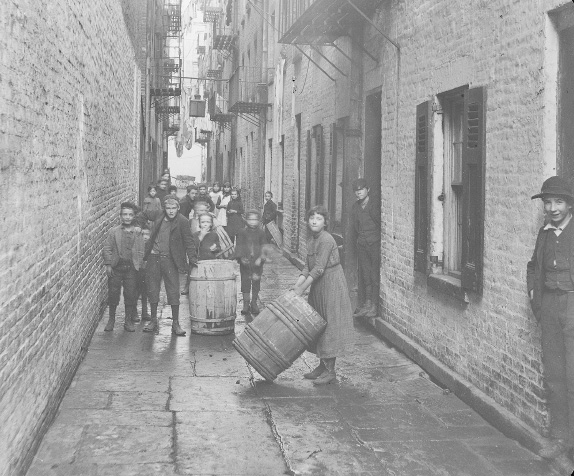

The longshoremen hired at the shape-up faced a hard day of dangerous labor. Climbing down into the holds, the men muscled the cargo into a sling, where it was lifted and deposited on the pier. More hands loaded wagons, called drays, that were waiting on the piers to move the freight to a warehouse, a factory, or another pier (fig. 5.1). The cargo destined for the railroads on the other side of the Hudson River was lifted from the holds and then placed onto flat-bottomed barges, or lighters, tied to the outboard side of the ship. A chaotic swarm of laborers filled the piers by day—and often into the night—and the harbor teemed with tugboats, lighters, and ferries moving the vast amounts of freight around the port. For ships departing from New York, the process was reversed. Drays delivered the outgoing freight, which was lifted aboard ship and then down into the hold, where the longshoremen stowed the cargo for the voyage.

Figure 5.1. Longshoremen, drays, and cargo made for a crowded pier on the East River. Sailing ships unloaded freight onto the piers, and horse-drawn carts (drays) hauled it off the piers. Longshoremen working the docks were picked in a shape-up. Source: Harper’s Weekly Magazine, July 14, 1877

The next day, longshoremen and pier workers moved on to find work on another ship. If nothing materialized, they drifted to the waterfront bars, to keep an ear open for news of a ship’s arrival. The Russell Sage study did not overlook the sterotype of the longshoremen: addicted to drink and habituated to life in the waterfront saloons. But the study did point out that when men were not hired for the day, they needed to wait nearby. The bars on South and West Streets provided shelter, warmth, comradery, and, of course, alcohol: “At his best, the longshoreman is a fair sample of humanity—honest, generous, interesting, and individual. . . . At his worst, he is all his critics accuse him of being. But blame for the drinking, to which he must plead guilty, falls largely on the conditions of his work.”2

Tens of thousands of workers made their livelihoods on the waterfront. This labor force included not only those men who worked the docks and drove the drays, but also the watermen who manned the tugboats, lighters, and ferries that traveled around the harbor. An army of men built and maintained the piers, dredged the slips, and worked in the hundreds of warehouses on the nearby streets.

No reliable data on the total employment generated by maritime commerce in New York’s port during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries exists. The Russell Sage study estimated that 35,000 men worked as longshoremen in 1914, and that number can be multiplied by a factor of ten to estimate the total maritime employment for that year.3 Moreover, the estimates do not include the sailors who manned the thousands of ships—operating across the oceans and along the coasts and inland waterways—that had New York as their home port.

The waterfront neighborhoods were as essential to the growth of the port as its physical infrastructure: wharves, piers, and waterfront streets created by the water-lot grants. Longshoremen and dockworkers needed housing as close to the waterfront as possible while waiting for the next shape-up. Since they could never be sure of steady employment or income, they crowded South and West Streets each day. The tenements on the adjacent streets provided shelter for their families, no matter how wretched the conditions there were otherwise. A tribal way of life flourished, and the neighborhoods took on the aura of a rural village back in Ireland or, later, Sicily or wherever the home country of the next wave of immigrants had been.

Immigration fueled the rise of New York City to become America’s entrepôt to the world, the leading industrial city in the country, a global center of finance, and the largest city in the United States. Immigration also provided the itinerant workforce needed for the port’s maritime commerce. On Manhattan Island, the population grew from 33,131 in the first federal census in 1790 to 1,850,093 in 1900. New York remained the fastest-growing place in the United States, and, without immigration, the population could never have increased so rapidly. At the turn of the twentieth century, a number of the city’s neighborhoods had some of the highest population densities on Earth.

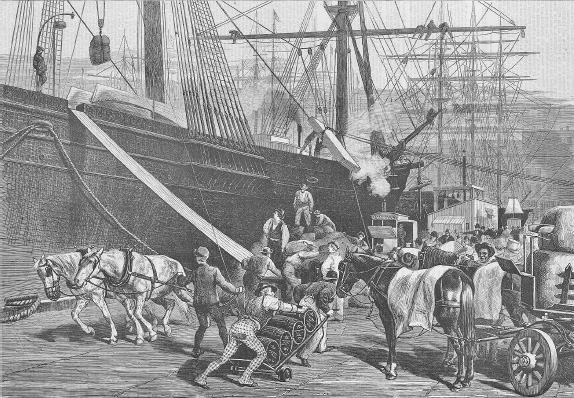

The pathway for millions of immigrants coming to America led across the Atlantic Ocean—on sailing ships and, later, steamships—to the Manhattan waterfront. Thousands and then millions came to the United States for religious and political freedom and for economic opportunity, despite the difficulties of the voyage and the struggle to gain a foothold in America. By the middle of the nineteenth century, immigrants from Ireland and Germany composed over one-third of the city’s population (table 5.1).4

The Irish, even from the beginning of their exodus to America and New York, found work on the waterfront. During the famine years, the most destitute settled in housing on the streets that were steps away from the piers along the East River, creating a distinctive Irish waterfront. The Russell Sage study reported that “as late as 1880, 95 percent of the longshoremen of New York . . . were Irish and Irish-Americans.”5 “Irish” referred to immigrants born in Ireland, and “Irish-Americans” to the first or second generation born in New York that had parents who came from Ireland.

Table 5.1.

New York City (Manhattan) foreign-born population from Ireland and Germany

Sources: New York [State] Secretary’s Office, Census of the State of New-York, for 1845 (Albany: Carroll & Cook, 1846); for 1850–1890, US Bureau of the Census, A Century of Population Growth from the First Census of the United States to the Twelfth, 1790–1900 (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1909).

By comparison, few German immigrants worked the waterfront. The Germans who came at the same time as the Irish were not impoverished, had much higher levels of education, and often worked at a skilled trade.6 The Germans found steady employment and did not have to face the shape-up to compete with others each and every day, as the Irish did. In addition, a number of German immigrants brought savings with them, which they used to open small retail, construction, and manufacturing businesses. The Germans who settled in the tenements in the Lower East Side in the 1850s stayed for a comparatively brief time period. As soon as they could afford to, they left the Lower East Side for Yorkville, on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, moving Kleindeutschland (Little Germany) far from the slums along the East River.

A spatial analysis of the 1880 census data,7 the first federal census to include household addresses, illustrates the ethnic makeup of four waterfront neighborhoods settled by the Irish: two along the East River (Wards 4 and 7) and two on the Hudson River (Greenwich Village and Chelsea). German immigrants clustered in Wards 11 and 17 on the Lower East Side, below East 14th Street, around Tompkins Square, which formed the center of Little Germany (map 5.1).

The 1880 census data for the waterfront neighborhoods and Little Germany illustrates the process of chain migration: newly arriving immigrants moved to neighborhoods where their countrymen already lived. Formal and informal systems of communication encouraged the newly arrived to find lodging where they would be welcomed. Clustering near relatives who had already settled on a block created dense ethnic neighborhoods.8 Hundreds of thousands of immigrants arrived each year, filling the worst of the city’s housing. The poorest of the poor had no choice but to live in atrocious conditions, and landlords had no incentive whatsoever to make improvements. If one family moved out, another trudged up the streets from the piers and moved in.

The Irish, both those born in Ireland and their first-generation children born in the United States, made up over a third (34.2%) of Manhattan’s population.9 In Wards 4 and 7, on the East River, the Irish totaled over 50 percent of the residents. In Ward 17, on the Lower East Side, the ethnic pattern was reversed: the Germans formed the majority of the population, with few Irish residents. On a smaller spatial scale, on the blocks adjacent to Tompkins Square in Ward 17, the ethnic segregation becomes even more striking. Manhattan, with only 18 percent of its population being native born, constituted a world apart from the rest of America, where the native-born made up 86.7 percent of the US population of 50 million in 1880. New York, during the century of immigration, became a populous multiethnic enclave, a process that continued up to the turn of the twentieth century, when ethnic tensions arose and nativism triumphed, leading to drastic immigration restrictions in 1924.

Map 5.1. Irish and German immigrant neighborhoods in 1880. The Irish were in wards 4 and 7 (on the East River), as well as in West Greenwich Village and Chelsea (on the Hudson River). The Germans were in Kleindeutschland, or Little Germany (wards 11 and 17). Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: building footprint map, New York City Planning Department.

Burroughs and Wallace state that by the middle of the nineteenth century, the Irish “took over the docks” along the East River. Each day, between 5,000 and 6,000 longshoremen filled the piers along the East River for the shape-up: “The work was hard, poorly paid and erratic. While waiting for ships to arrive or weather to clear, men hung around the local saloons, took alternative jobs as teamsters, boatmen or brick makers, and relied on the earnings of their wives and children.”10 In the Irish waterfront neighborhoods, economic stability remained elusive.

Many of the famine Irish settled along the waterfront on the East River, in Ward 4. After a voyage lasting two months or longer, the immigrants simply walked off the ship onto the piers lining South Street and carried their meager belongings a block or two up Roosevelt, James, or Oliver Streets to a tenement or a cheap boarding house.

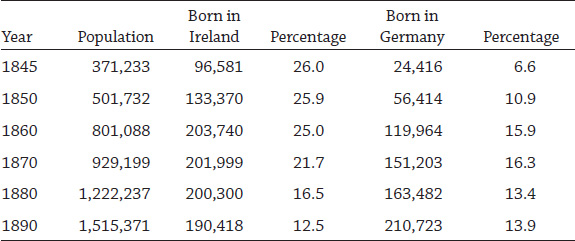

The area along the East River around Roosevelt Street, Cherry Street, Pecks Slip, and Franklin Square formed part of Ward 4, where the 1850 US census reported a total population of 23,123.11 Chatham Square formed the northern boundary and Ward 4 included all streets down to the waterfront. An 1881 map of the area shows the construction of the approaches to the Brooklyn Bridge on Franklin Square (map 5.2). From there, Cherry Street runs east and crosses Roosevelt, James, and Oliver Streets. Men from Ward 4 worked the docks and at the Fulton Fish Market, which supplied the city with fresh seafood.

The 1880 census subdivided Ward 4 into eleven enumeration districts (EDs), and the area along Cherry Street formed ED 33. In that ED, the population totaled 1,788 residents, but only fifty-one individuals (2.9%) were native, meaning they and both of their parents were born in the United States. By comparison, over 74 percent of the population in the ED was Irish, either born in Ireland or first-generation (born in the United States). In Manhattan, the German immigrants nearly equaled the Irish in numbers, but only eighty-nine Germans lived in ED 33. Intense ethnic segregation characterized Ward 4 and other Irish waterfront neighborhoods, as it did in Kleindeutschland, farther to the north in the Lower East Side.

Map 5.2. Ward 4, Enumeration District 44, on the East River. The numbers on the map indicate the foundation for the Brooklyn Bridge (1); Gotham Court (2), at 34 and 36–38 Cherry Street; and Oliver Street (3), the childhood home of Al Smith, a governor of New York and Democratic candidate for president of the United States in 1928. Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: historic street map, New York Public Library, Map Warper.

Alfred Smith, the famous Tammany politician, governor of New York, and the first Catholic to run for president of the United States in 1928, was born in 1871 on Oliver Street, in Ward 4. His mother’s parents immigrated to New York from Ireland, and his father’s parents came from Italy and Germany. Smith described his childhood as growing up in the “shadow of the Brooklyn Bridge.”12 An early biography of Al Smith described Ward 4 in lurid detail: “This book is the story of a boy who grew up in a region where Tammany Hall was supreme. The Fourth Ward and the parish of St. James in which he lived were surrounded by poverty and vice in terrible forms. . . . He is the first of our national heroes to be born amidst din and squalor. . . . Life on the East Side of New York when Alfred Smith was born was an even fiercer struggle for existence than it is today [1927].”13 While successive waves of immigrants would come to Ward 4 from across Europe, “before any of these large tides of immigration, there arrived the Irish.”14

Residential buildings in the neighborhood, originally constructed for a single family, were quickly subdivided into tiny apartments, like the one Al Smith’s family lived in on Oliver Street. Landlords often built a second shoddy structure in the rear yard, to cram in more immigrants. The wretched housing available to the Irish included some of the most shameful in the city and led to reform efforts involving well-to-do New Yorkers appalled by the Tammany corruption and the complete failure of the city government to respond. In the 1850s, Peter Cooper and a group of wealthy activists formed the Citizens’ Association of New York. The association’s first major initiative focused on public health and demanded that the New York Legislature establish a health department independent of Tammany Hall. In Albany, the political allies of the association in the legislature introduced a bill in 1859 to form a health department, but that failed, given the fierce opposition from the Tammany machine. The Civil War intervened, but the draft riots in 1863 strengthened the reformers’ conviction of the need for “social hygiene” in the immigrant tenement districts, such as Ward 4. The alternative promised continued chaos and social unrest. Finally, in 1866, the legislature passed a bill establishing the independent Metropolitan Board of Health for New York City and the adjacent counties. The law required that at least three of the commissioners were to be physicians, not Tammany political hacks.

While waiting for the state legislature in Albany to act, in 1864 the Citizens’ Association funded a major study of the social and health conditions in the city’s neighborhoods, including Ward 4. The association’s Council of Hygiene and Public Health completed a study of the “sanitary condition of the city.”15 The Council divided the city into twenty-nine sanitary districts. In each district a research team, headed by a doctor, conducted an exhaustive door-to-door survey of the tenements and the people living in them. The investigators gathered health data and inspected 15,511 tenements, which were home to 486,000 residents, over half of the city’s total population of 813,669 in 1860. In Ward 4, the study identified 486 tenements, with 17,957 residents, or three-quarters of the ward’s total population of 21,944 enumerated in the 1860 US census.

Ezra E. Pulling, MD, authored the report for the Fourth Sanitary District, which included the entirety of Ward 4. This sanitary report documented in grim detail the appalling conditions in the immigrant neighborhoods. Pulling listed the streets in the district that had no sewers and then added that those streets with sewers “empty into the East River.” He noted that most of the human waste in a city of over 800,000 emptied into the East or Hudson Rivers, and, if not, “liquid refuse [human waste] is emptied on the sidewalk or into the street, in some instances into sinks [underground vaults] in the domiciles communicating with a common pipe which discharges its contents into an open gutter to run perhaps a hundred feet, giving forth the most noisome exhalation, and uniting its fetid streams with numerous others from similar sources.”16

In an era before the acceptance of the germ theory of disease, Pulling and the other physicians believed the cause of disease to be miasma, or “bad air.” Specifically, this fetid air emanated from privies, open latrines, and sewers and was combined with the lack of ventilation in the crowded tenements. The reports for the other twenty-eight sanitary districts all focused on bad air in the tenements, privies, and the city’s rudimentary sewer system. All of the reports claimed that this miasma caused the appalling health of the city’s poorest residents, who were forced to live in the tenements.

Of the 1,507 buildings in Ward 4, 682 were businesses, 8 were churches or schools, 47 were stables, and 770 were primarily residential buildings. The investigators not only counted but also categorized the residential buildings, classifying 740 of them as “tenement[s] and crowded houses.” Among these, 472 were single-family homes that had been converted to tenements, and 242 were built as tenements. Of the 770 residential buildings, 96.1 percent were identified as overcrowded tenements, and 108 of them included a second tenement building in the rear lot.17

The Pulling report describes a typical tenement house, using a dwelling on Jane Street as an example: a brick building, five stories tall, with a hall 4.5 feet wide; stairs 2.5 feet wide, in perpetual darkness; and four two-room apartments on each floor. One room measured 14 × 12 feet and the second 9 × 12 feet, with a coal stove and no window. The bedroom contained two beds and bedding on the floor. It was “a dormitory of half a dozen persons. A sickening and stifling odor, most offensive to the unaccustomed sense pervades this apartment and poisons the atmosphere inhaled by the residents.”18

Charles Dickens visited New York in 1842 and toured Five Points, the infamous Irish slum north of Ward 4, where Chinatown is today. He continued his journey south into Ward 4 and visited one of the most notorious tenements in Manhattan: Gotham Court, on Cherry Street (map 5.2, #2). For almost fifty years, thousands of Irish immigrants and their children resided in Gotham Court. The men living there found work on the piers lining the East River.

Figure 5.2. Gotham Court, at 34 and 36–38 Cherry Street, was three blocks from the East River. This crowded, stinking slum was one of the many tenements that were home to the Irish longshoremen who worked the docks. Source: Museum of the City of New York

In 1850, Silas Wood, a wealthy landowner in Ward 4, constructed a massive tenement complex, known as Gotham Court, on Cherry Street, between Roosevelt Street and Franklin Square. Wood built two buildings—numbers 34 and 36–38 Cherry Street (fig. 5.2). Each stood six stories high, 250 feet in length by approximately 35 feet wide. Apartments on each floor measured 10 × 14 feet, divided into two rooms.19 Two alleys, East and West Gotham Place, ran along the side of the buildings, allowing access to the stairwells. Privies and sinks were located in the cellars, which required the residents to climb up and down stairs. Grates in the alleys provided some ventilation for the reeking privies.

Pulling’s report found seventy-one families living in Gotham Court, with a total of 504 residents, an average of seven persons for each cramped two-room apartment. The filthy apartments stank, due to “no small portions of their own excretions, as it is painfully evident to everyone who has . . . an acute sense of smell.”20 Among the families who lived in the Court in the previous two years, there had been 138 births, including twelve babies that were stillborn. Only seventy-seven infants survived to the age of 2, a mortality rate of over 44 percent. To a modern sensibility, the number of infant deaths in Gotham Court would be a health crisis. For the mothers and fathers who watched their babies die, their grief must have been unbounded. Only the poorest Irish immigrants lived in the Court, as evidenced by the forty-nine vacant apartments. They must have recognized the danger to their children’s health, and those with means left, even if they moved to another tenement a block away. Pulling’s report also included detailed descriptions of horrific conditions in other Ward 4 tenements. He argued that while Gotham Court had a reputation as one of the worst, “on the whole . . . Gotham Court presents about the average specimen of tenant-housing in the lower part of the city. . . . There are some which are more roomy, have better ventilation and are kept cleaner; but there are many which are in far worse condition.”21

Obtaining decent food proved to be especially challenging. The small grocery stores, including one in Gotham Court that faced Cherry Street, sold ghastly food, which was often tainted and “unfit for human consumption.” In addition to the spoiled food, the stores sold the then-legal narcotics that many used to dull their senses. The grocers, who often also owned tenements in the neighborhood, mercilessly overcharged their customers. With so little income, the residents often bought on credit and found themselves in debt for both rent and food, held in “a state of abject dependence and vassalage little short of absolute slavery.”22

In Ward 4, 134 small groceries sold food, with one shop for every twenty-seven families. The number of “drinking places” totaled 446, with one for every eight families. In addition to numerous saloons on every block, there were twenty-eight brothels and six “sailor’s dance-houses.” Herman Melville’s autobiographical novel Redburn includes vivid descriptions of the bars and brothels along the East River waterfront in Ward 4.

Pulling ends his sanitary report with a surge of moral outrage at the horrid conditions his investigations uncovered. He foreshadows Jacob Riis and other reformers who demanded that the city’s government respond to save the lives of people condemned to live in Gotham Court, Ward 4, and the other immigrant neighborhoods. Pulling called for the removal of one-half of all the tenements and demanded that if private interests would not build decent housing, it “should become a subject of municipal and legislative action.”23 It would be half a century before a government, at any level, even imagined an obligation to ensure decent housing for the poorest of citizens and, in the case of New York City, the millions of immigrants who would follow the Irish and Germans.24

An 1879 article about Gotham Court in Harper’s Weekly Magazine included direct quotes in the native brogue of the Irish residents describing the difficulties they faced. One resident, who paid $4 a month in rent, lamented about her desperate situation:

Nearly every room on the lower floor was found to be like those just described—small, dark, and dirty—and every tenant had her grievances which she poured forth at the first opportunity. “Bad luck t’ them,” said one. “I fill intil the cellar lasht week—how cud I help it, Sir—and hurt meself bad, so I did.” She was a sad-faced creature. . . . She was obliged to live there, she said, because she was desperately poor. “Not a cint comin’ in but tin cints [ten cents] a noight from two girls as lodges wi me, and whatever ’ll I do now? Wan o’ them’s jisht come in from work wi her fut shprained. She’s lyin’ on the bed in there.”25

The article in Harper’s depicts Danny Burke, at 4 years old the youngest newsboy in New York City, who sells the Evening Telegram paper on the corner for 2 cents. The writer meets Danny in a stairwell and asks a woman, who praised the boy’s hard work, if Danny was her son. “No, Sir,” she answered, “he belongs to the woman up shtairs, but I’ve wan insoide that ’ll match him. Luk at that, Sir,” and she pointed to a little one sleeping in the cradle. A man standing in the hallway told the reporter that the woman “had twelve o’ them, Sir.” The reporter asked the woman, “Are they all living?” She thought for a while and then related sadly, “No, Sir, risen [seven] o’ than are dead.” Seven of her twelve children had died in infancy while living in Gotham Court.

The 1880 census found seventy-two families living in Gotham Court—almost the same number as in Pulling’s sanitary report a decade earlier—but counted far fewer residents: 299 versus 504. The average family size in 1880 was 5.5, versus 7 a decade earlier.26 Yet even with fewer residents and smaller families, Gotham Court still remained crowded, where a family of four or five shared two small rooms. Among these seventy-two families, fifteen women headed households, all of them widows. Elizabeth Daly, age 42, and Mary Mulcahey, age 52, both Irish immigrants, lived next door to each other. Elizabeth’s three children—Ellen, age 29; Mary, age 26; and Peter, age 21—all worked to provide the family with income. Both girls, who were unmarried, worked in a paper-box factory, and Peter found low-paid employment as a day laborer. Mary Mulcahey had a 10-year-old daughter who attended school, most likely St. James Catholic School around the corner, Al Smith’s grammar school. No employment was listed for Mary.

Three blocks down the hill from Cherry Street, the piers on South Street teemed with maritime commerce. Longshoremen from the neighborhood gathered there early each morning, in all seasons, for the shape-up. Among the fifty-seven men with families living in Gotham Court, fourteen worked as longshoremen, almost 25 percent. All of the longshoremen except John Sullivan, born in New York in 1830, were Irish immigrants. Both of Sullivan’s parents had emigrated from Ireland before the potato famine. The Irish longshoremen who had families and were living in Gotham Court included James Casey, age 38, with four children: ages 6, 4, 2, and a new baby born in 1880. The census listed another longshoreman resident, James O’Connell, age 54, as not able to read or write. He and his wife Margaret had five children. The three oldest—Johanna, age 23; Patrick, age 20; and Daniel, age 17—all worked. Margaret remained home with their daughter Margaret, age 13, and son John, age 11. Only John attended school. The longshoremen’s wives remained at home, but in all the families, the older children had to work down on the docks to provide additional income to pay expenses, including the rent at Gotham Court.

Given the dangerous nature of the longshoremen’s work, injuries were common. Daniel Murphy, who broke his jaw working the piers, reported no income for five months. His neighbor, John Costello, was out of work for four months. Daniel and his wife Mary had one child—Mary, age 20—who worked in a paper-box factory nearby and provided the only reported income the family had for part of the year. Few residents of Gotham Court had good jobs that paid a decent income. If they did, they would have left Cherry Street for more-decent housing.

Jacob Riis, in The Battle with the Slum, refers to Gotham Court as “the tenement that has challenged public attention more than any other in the whole city and tested the power of sanitary law and rule for forty years.”27 The owners refused to make any improvements to protect the health of the residents. The health inspector for the district reported that “nearly ten percent of the population [of Gotham Court] is sent to the public hospitals each year.”28 While advocating for change, Riis, in his powerful How the Other Half Lives, also offers the worst stereotypes to describe the poor Irish residents there: “A Chinaman whom I questioned as he hurried past the iron gate of the alley, put the matter in a different light, ‘Lem Ilish velly bad,’ referring to the Irish immigrants and their children who lived in the Court.”29 Despite the damning sanitary reports, the Harper’s story in 1879, and Riis’s How the Other Half Lives, Gotham Court would not be demolished until 1895. The Irish continued to fill the apartments in Ward 4 for decades, including the notorious slum on Cherry Street.

Writing in 1902, Jacob Riis reminds readers of just how horrific life had been in this rookery:

Look at Gotham Court, described in the health reports of the sixties as a “packing-box tenement” of the hopeless back-to-back type, which meant that there was no ventilation and could be none. The stenches from the “horribly foul cellars” with their “infernal system of sewerage” must needs poison the tenants all the way up to the fifth story. I knew the Court well, knew the gang that made its headquarters with the rats in the cellar, terrorizing the helpless tenants; knew the well-worn rut of the dead-wagon and the ambulance to the gate, for the tenants died there like flies in all seasons, and a tenth of its population was always in the hospital.30

Riis condemned the moral failure of the landlords who owned the horrific tenements and who fought every reform effort: “Think of the living babies in such hell-holes; and make a note of it, you in the young cities who can still head off the slum where we have to wrestle with it for our sins. Put a brand upon the murderer who would smother babies in the dark holes and bedrooms. He is nothing else.”31 Emphasizing the dignity of every human being, no matter how poor, in moral and religious language, Riis’s words would find an echo in calls for change on the waterfront in the twentieth century. The longshoremen who still lived in the dank tenements deserved the right to better working conditions on the piers, where the shape-up, the loan sharks, and the mobsters made a mockery of man’s basic human right to dignity.

The city’s maritime world had its beginning along the East River, but the unceasing demand for pier space stimulated the development of the Hudson River waterfront. The sizes of ships coming from Liverpool, Europe, and elsewhere around the world had increased dramatically. Much longer piers could be built along the Hudson, and transatlantic shipping, for both cargoes and passengers, moved to the West Side of Manhattan. When the Department of Docks took over, the original piers on the Hudson River were already obsolete. The department removed the old piers and constructed much longer piers, in order to accommodate the new generation of ships. The development of the new piers, warehouses, and factories on the adjacent blocks drew more shipping—and the railroads—to the Hudson River side of the island. The railroads and the transatlantic steamship companies signed long-term leases with the Department of Docks, to ensure access to the waterfront.

The history of Greenwich Village and Chelsea goes back to colonial times, when the area offered a bucolic retreat for wealthy residents seeking to escape the crowded, unsanitary conditions in the city, which then was a mile to the south at the tip of Manhattan Island. With the shift in shipping to the Hudson River, the Irish longshoremen followed, and both Greenwich Village and sections of Chelsea became Irish enclaves (see map 5.1). James Fisher’s account of the Irish waterfront chronicles the transfer of port activity first to the Greenwich Village waterfront and then north to Chelsea: “The focus [of the Department of Dock’s rebuilding of the piers] soon shifted almost entirely to the Lower West Side. . . . In 1897 the department supervised construction of municipally owned piers—upwards of seven hundred feet long—on riverfront terrain between Charles and Gansevoort Streets. The West Side’s Irish waterfront coalesced around the imposing new structures before expanding northward up the Hudson shoreline [to Chelsea].”32 Just as in Ward 4, residential buildings on the streets leading down to the Hudson waterfront, originally built for one family, became tenements. Both the Village and Chelsea had more native-born residents than the city as a whole, and more ethnic diversity than either of the Irish neighborhoods along the East River.33

The Greenwich Village waterfront included the blocks west of Hudson Street, extending to the river between Houston and West 14th Streets (map 5.3). In response to the number of Irish Catholics moving to Greenwich Village, the Archdiocese of New York established St. Veronica’s parish in 1887. An old stable on Washington Street served as the church during construction. The first mass was celebrated in 1903 in the new church at 153 Christopher Street (map 5.3, #3). St. Veronica’s played an important role on the Irish waterfront.

In the Village, the neighborhood became more Irish on the blocks closest to West Street and the waterfront. The first blocks inland from the Hudson River—West Street to Washington or Greenwich Streets—had a much higher concentration of Irish than blocks farther east (map 5.4). In addition, ED 218, between Washington and Greenwich Streets, just south of Leroy Street, had the highest percentage of Irish in the Village, 60.8 percent. Living close to the Hudson provided the Irish longshoremen and dockworkers with quick access to the Christopher Street piers. Stuart Waldman’s study of the Greenwich Village waterfront confirms that as soon as the Department of Docks completed the new Hudson River piers, hundreds of new tenements were built on the adjoining streets, to which the Irish moved.34

The 1865 report for Sanitary District 5B included the blocks from Houston to Christopher Streets along the Hudson River. Some of the tenements, once single-family homes, “are now crowded [with] from four to six families, averaging five persons each.”35 North of Christopher Street, Sanitary District 11 included the blocks up to West 14th Street. The streets near Gansevoort were described as “always filthy.” The deficiencies of the sewerage system, especially the sewer under Gansevoort Street, which did not empty into the Hudson River, allowed human waste to flow into an open trench. The residents living on the blocks around the open trench—Gansevoort, West, Washington, and Horatio Streets—suffered “no less than 29 cases of dysentery and diarrhea, 5 of which had terminated fatally” in one three-week period.36

Map 5.3. Greenwich Village, from Charles to Clarkson Streets. The numbers on the map indicate Charles Place (1), known as “Pig Alley”; the Empire Brewery (2); St. Veronica’s Catholic Church (3); warehouses (4); waterfront bars (5); and Hudson River piers (6). Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: historic street map, New York Public Library, Map Warper.

Once established in Greenwich Village, the Irish dominated its waterfront for the next forty years, even as immigration patterns to the city changed dramatically. In the latter half of the nineteenth century, the number of immigrants from Ireland and Germany declined, while the numbers arriving from eastern and southern Europe increased. The Germans in the Lower East Side moved out to Yorkville, to be replaced by millions of eastern European Jews fleeing persecution and poverty in the Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires. In southern Italy and Sicily, life became increasing precarious, with few economic opportunities. America beckoned as the Promised Land. Young men from Italy traveled alone in the 1890s to find work in New York, and then either brought their families over or returned home. Despite the influx of these new immigrants, the Irish held on to their waterfront jobs and remained in the Village waterfront.

Map 5.4. The Greenwich Village waterfront, showing the 1880 census enumeration districts. The numbers indicate the percentage of Irish in each outlined area, which includes those born in Ireland plus first-generation Irish (born in the United States, but whose parents were born in Ireland). Source: Created by Kurt Schlichting. Source GIS layer: building footprint map, New York City Planning Department. Other sources: 1880 enumeration district map, Milstein Division, New York Public Library; “NAPP 1880 US Census, 100% Enumeration” [with individual-level data aggregated to the 1880 enumeration districts], Steven Ruggles, Katie Genadek, Ronald Goeken, Josiah Grover, and Matthew Sobek, Integrated Public Use Microdata Series: Version 6.0 [database] (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota, 2015), North Atlantic Population Project, https://www.nappdata.org/napp/.

Over time, as the ethnic makeup of Manhattan changed, Greenwich Village did not. Between 1880 and 1920, over 35 percent of the population was born in Ireland or had parents who were.37 For Manhattan as a whole, the percentage of Irish declined, from over 30 percent of the population in 1880 to 12 percent by 1920. Yet the tribal world on the Irish waterfront persisted.

Chelsea is generally considered to be the area that runs north of West 14th Street to West 26th Street, although the neighborhood’s boundaries have always been a matter of debate. Clement C. Moore’s property along the Hudson River above Greenwich Village long remained an undeveloped part of Manhattan (see map 2.4). With the dramatic increase in the size of ships coming to the port, when the Department of Docks took over the waterfront in 1870, they realized that the Chelsea section provided the most practical location for the massive piers needed to accommodate the large White Star Line and Cunard Line ocean liners. Their foresight was confirmed when, decades later, the opening of the Chelsea piers in 1902 signified a new era in transatlantic travel.

Even long before these piers were constructed, increased maritime activity on the waterfront drew the Irish to the Chelsea neighborhood. They also found work in the iron and brass factories, such as the Williams Ornamental Brass and Iron Works on West 26th Street and the Colwell Iron Works, around the corner on 11th Avenue, between 27th and 28th Streets, which were part of the city’s thriving industrial economy.38 The Consolidated Gas Company, which employed many immigrants, occupied four blocks: from 16th to 20th Streets, between 10th and 11th Avenues. An 1891 Bromley map depicts the early development of the shorefront before the construction of the Chelsea piers, when 13th Avenue would disappear, to be replaced by West Street (see map 7.3).

In the rush to construct tenements in Chelsea as the waterfront expanded and factories and train yards filled the adjoining blocks, landlords and developers crammed as much housing as possible on each block. The 1865 sanitary report labeled this the “massing of tenements.” On each lot, a tenement occupied the street front, and a second building filled most of the rear of the lot, with the privies in between. A typical city lot in Chelsea measured 30 × 100 feet. On a single block, developers built twenty houses, “each twenty feet wide, and as high as it pleases the owner to rear them . . . on a space less than 20,000 square feet; and allowing each front house to contain eight, and each rear house four families (a modest estimate), we have each family [living in] about 164 square feet of ground.”39 East of 9th Avenue, on 26th Street, where the Irish lived, the report included a drawing of the massed tenements, labeled “Bird’s-Eye View of a New Fever-Nest on the Avenues.”40

The social geography of Chelsea mirrors that of Greenwich Village, with the Irish concentrated on specific blocks: 9th and 10th Avenues between 14th and 17th Streets, and along West Street and the Hudson River from 25th to 29th Streets. In these EDs, the Irish constituted over 70 percent of the residents. At the time of the 1865 sanitary report, rank tenements filled parts of Chelsea, particularity along the Hudson around West 26th Street, in ED 341. The survey counted a total of 1,154 residential buildings and tenements. In the more affluent sections of Chelsea, where the Irish did not live, new residential buildings included “all the modern improvements, such as the introduction of [manufactured] gas, Croton-water, baths, furnaces, water-closets and proper sewer connections.”41 “Croton-water” referred to New York City’s new, massive public water system that drew fresh water from a series of reservoirs in Westchester County, north of the city. Water-closets included a flush toilet. By comparison, the sanitary conditions in the tenements in the Irish sections, even those that were recently constructed, remained “defective,” with no connections to the sewers. In one building on West 22nd Street, forty-two people shared privies in the damp and dark cellar, with no ventilation, which was described as “worse than a Stygian pit.”42

In a developing neighborhood like Chelsea, the social makeup could change significantly from block to block, and some of the streets included luxurious single-family homes for the wealthy and the family’s three or four live-in servants. Clement Moore leased his land from 9th to 10th Avenues, between 22nd and 23rd Streets, to William Torey, who built eighty four-story brownstone townhouses in 1845, each leased as a private residence. The General Theological Seminary occupied the block two streets to the south. Before the Great Depression a developer, Henry Mandel, took over the leases from the Moore descendants, tore down the townhouses, and constructed the high-rise London Terrace building, with over 1,700 apartments, which attracted well-to-do business executives and their families.43

Despite upscale developments like London Terrace, sections of the Chelsea waterfront remained an Irish enclave into the post–World War II era. The International Longshoreman’s Association, the notorious union that represented the waterfront laborers, located its first headquarters on West 14th Street. In the years to come, the pastor of Guardian Angel Church on 10th Avenue and the Jesuit pro-labor priests who taught at Xavier High School on West 16th Street would wage an epic battle for what Fisher called “the soul” of the Irish waterfront.44