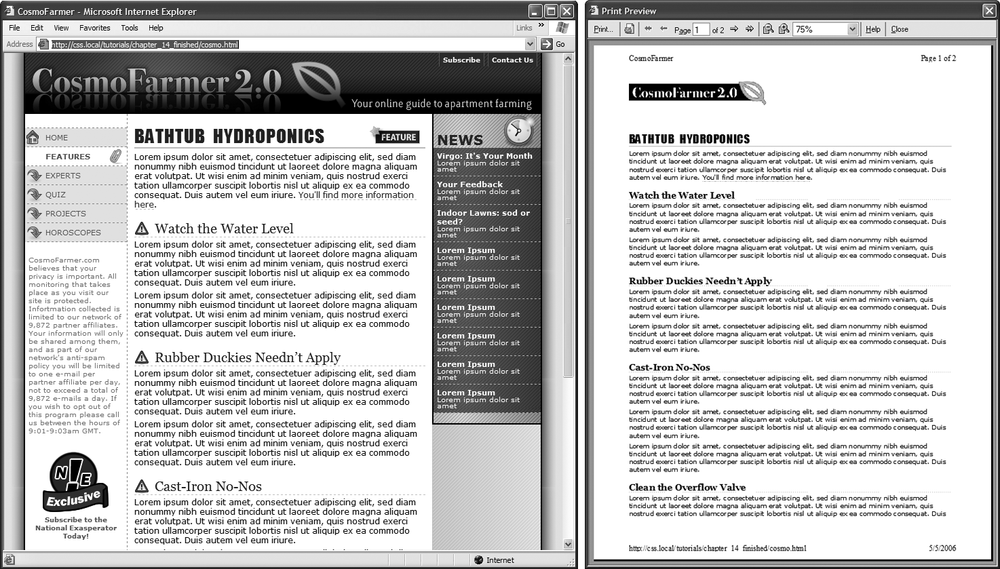

First, see how pages on your site print before embarking on a print-specific redesign. Often, all the information on a web page prints without problems, so you may not have to add a printer style sheet to your site. But in some cases, especially when using heavy doses of CSS, pages look awful printed. For example, since web browsers don't print background images unless instructed to, you might end up with large blank spaces where those background images were. But even if a page looks the same in print as it does on the screen, you have many ways to improve the quality of the printed version by adding custom printer-only styles (see Figure 14-2).

Figure 14-2. When printing a web page, you really don't need navigation links or information that's not related to the topic at hand. With a printer style sheet, you can eliminate sidebars, navigation bars, and other content designed for web browsing (left). The result is a simply formatted document—perfect for printing (right).

Tip

A quick way to see how a page will print without wasting a lot of paper and toner is to use your browser's Print Preview command. On Windows this is usually available from a web browser's File → Print Preview menu. On Macs, you usually first choose File → Print, and then click Preview in the window that appears. Using Print Preview you can check to see whether a page is too wide to fit on one page and see where page breaks occur.

As mentioned earlier, it's often useful to create a style sheet without specifying a media type (or by using media="all"). When you're ready to define some print-specific rules, you can just create a separate style sheet to override any styles that don't look good in print.

Say you've got an <h1> tag that's styled to appear blue onscreen, and you've also chosen rules controlling letter spacing, font weight, and text alignment. If the only thing you want to change for your printed pages is to use black rather than blue, then you don't need to create a new style with a whole new set of properties. Just create a main style sheet that applies in both cases and a print style sheet that overrides the blue color for the <h1> tag.

One problem with this approach is that you need to make sure the printer styles actually do override the main style sheet. To do this successfully, you have to carefully manage the cascade. As discussed in Chapter 5, styles can interact in complex ways: Several styles may apply to the same element, and those styles' CSS properties can merge and override each other. There's a surefire way to make sure one property trumps all others—the !important declaration.

When you add !important after the value in a CSS declaration, that particular property overrides any conflicts with other styles. Add this rule to a print style sheet to ensure that all <h1> tags print black:

h1 {

color: #000 !important ;

}This h1 style overrides even more specific styles, including #main h1, h1.title, or #wrapper #main h1 from the main style sheet.

You may not necessarily want to have text look the same onscreen as it does in print. A good place to start when creating a printer style sheet is by modifying the font-size and color properties. Using pixel sizes for text doesn't mean much to a printer. Should it print 12-pixel type as 12 dots? If you've got a 600 DPI printer, that text will be illegibly small. And while bright green text may look good onscreen, it may come out a difficult-to-read pale gray when printed.

Pixels and ems (Using Pixels) make sense for onscreen text, but the measurement of choice for printing is points. Points are how Word and other word-processing programs measure font sizes, and they're what printers expect. In practice, most web browsers translate pixel and ems to something more printer friendly anyway. The base onscreen font size for most browsers—16-pixels—prints out as 12 points. But there's no consistent way to predict how every browser will resize text, so for maximum printing control, set the font size specifically to points in your print style sheets.

To make all paragraphs print in 12-point type (a common size for printing), use the following rule:

p {

font-size: 12pt;

}Likewise, screen colors don't often translate well when printed on a black-and-white laser printer. Crisp black text on white paper is much easier to read, for instance, than light gray letters. What's more, as you'll see in the next section, white text on a black background—though very legible onscreen—often doesn't print well. To make text most readable on paper, it's a good idea to make all text print black. To make all paragraph text black, add this style to your print style sheet:

p {

color: #000;

}As mentioned on the previous page, if your print style sheet competes with styles from another attached style sheet, then use !important to make sure your printer styles win:

p {

font-size: 12pt !important;

color: #000 !important;

}To make sure all text on a page prints black, use the universal selector (Constructing Group Selectors) and !important to create a single style that formats every tag with black text:

* { color: #000 !important }Of course, this advice applies only if your site is printed out in black and white. If you think most visitors to your site use color printers, then you may want to leave all the text color in or change the colors to be even more vibrant when printed.

Adding background images and colors to navigation buttons, sidebars, and other page elements adds contrast and visual appeal to your web pages. But you can't be sure if the background will come through when those pages are printed. Because colored backgrounds eat up printer ink and toner, most web browsers don't normally print them, and most web surfers don't turn on backgrounds for printing even if their browser has this feature.

In addition, even if the background does print, it may compete with any text that overlaps it. This is especially true if the text contrasts strongly with a colorful background on a monitor but blends into the background when printed on a black-and-white printer.

Note

White text on a black background used to pose the biggest problem—your visitor would end up with a blank white page. Fortunately, most current web browsers have the smarts to change white text to black (or gray) when printing without backgrounds.

The easiest way to take care of backgrounds is to simply remove them in your print style sheet. Say you reverse out a headline so that the text is white and the background is a dark color. If the style that creates that effect is named .headHighlight, then duplicate the style name in your print-only style sheet, like this:

.headHighlight {

color: #000;

background: #FFF;

}This style sets the background to white—the color of the paper. In addition, to get crisp printed text, this style sets the font color to black.

If you don't want to get rid of the background, you can leave it in and hope that visitors set their browsers to print them. If you leave background elements in your print style sheet and text appears on top of them, then make sure the text is legible with the backgrounds on and off.

Another thing to consider when using background images: Do you need the image to print out? Say you place a company's logo as a background image of a <div> tag used for the banner of a page. Because the logo is in the background, it may not print. Your company or client may not be happy when every page printed from their site lacks a logo. In this case, you've got a few options. You can insert the logo as a regular <img> tag instead of a background image. This technique works, but what if the logo looks great on a full-color monitor but no good at all when printed on a black-and-white printer? Another technique is to leave the logo in as a background image and add another, more printer-friendly logo using the <img> tag. You then hide that <img> tag onscreen but show the printer-friendly logo when printed. Here's how:

Add the <img> tag to your HTML in the spot where you want it to appear when printed:

<img src="logo.png" height="100" width="100" id="logo" />

Then, in the main style sheet (the one that applies when the page is displayed on screen), add a style that hides that image:

#logo { display: none; }In the print style sheet, add one last style to display the image:

#logo { display: inline; }

Now that logo won't appear on screen, but will when printed.

Tip

If you want to be absolutely sure that a background image prints, there's another tricky CSS workaround for overcoming a browser's reluctance to print background images. You can find it here: http://web-graphics.com/mtarchive/001703.php

Web pages are often loaded with informational and navigational aids like navigation bars, sidebars full of helpful links, search boxes, and so on. These elements are great for surfing the Web, but don't do much good on a piece of paper. Your web pages may also contain ads, movies, and other doodads that people don't like to waste expensive ink and toner on. You can do your visitors a favor by stripping these onscreen frills out of the content they really want to print.

As you learned in of the third part of this book, one way to lay out a page is to wrap <div> tags around different layout elements—banner, main navigation, content, copyright notice, and so on. By styling each <div> using floats or absolute positioning, you can place various page elements right where you want them. You can use that same structure to create a print-only style sheet that hides unwanted elements using the display property.

By setting the display value to none, you can make a web browser remove a styled element from a page. So to prevent a sidebar from printing, simply redefine that style in a print style sheet and set its display property to none:

#sidebar {

display: none;

}For most pages, you want the print style sheet to display only the most basic informational elements—like the logo, the main content, and a copyright notice—and hide everything else. You can easily hide multiple elements with a group selector, like so:

#banner, #mainNav, #sidebar, #ads, #newsLinks {

display: none;

}Remember, these styles go into your print style sheet, not the main style sheet. Otherwise, you'd never see the navigation, banner, or other important areas of your page onscreen. However, at times you might want to hide something from your main style sheet and reveal it only when printed.

Say you place your site's logo as a background image inside the banner area of a page. You may want to do this to have text or links appear on top of an empty area of the logo graphic. You (or your boss or client) certainly want the logo to appear on any printed pages, but since not all browsers print background images, you can't be sure the logo will appear when printed. One solution is to insert an <img> tag containing a modified, printer-friendly version of the logo graphic; add an ID to the image; create an ID style in the main style sheet with the display property set to none; and then set the display property for the same ID style in the print style sheet to block. Voilà! The logo appears only when printed.

Version 2.1 of the Cascading Style Sheet standard includes many CSS properties aimed at better formatting a printed web page: from setting the orientation of the page to defining margins and paper size. (You can see the full list at www.w3.org/TR/CSS21/page.html.) Unfortunately, today's web browsers recognize very few of these print styles.

Two widely recognized properties are page-break-before and page-break-after. Page-break before tells a browser to insert a page break before a given style. Say you want certain headings to always appear at the top of a page, like titles for different sections of a long document (see Figure 14-3). You can add page-break-before: always to the style used to format those headings. Likewise, to make an element appear as the last item on a printed page add page-break-after: always to that element's style.

The page-break-before property is also useful for large graphics, since some browsers let images print across two pages, making it a little tough to see the whole image at once. If you have one page with three paragraphs of text followed by the image, then the browser prints part of the image on one page and the other part on a second page. You don't want your visitors to need cellophane tape to piece your image back together, so use the page-break-before property to make the image print on a new page, where it all fits.

Here's a quick way to take advantage of these properties. Create two class styles named something like .break_after and .break_before, like so:

.break_before { page-break-before: always; }

.break_after { page-break-after: always; }You can then selectively apply these styles to the elements that should print at the top—or bottom—of a page. If you want a particular heading to print at the top of a page, then use a style like this: <h1 class="break_before">. Even if the element already has a class applied to it, you can add an additional class like this: <h1 class="sectionTitle break_before">. (You'll learn about this useful technique in the next chapter on Use Multiple Classes to Save Time.)