Key points

- Managing Type 2 is as much a matter of managing the mind as medication and diet.

- Most people don’t have major psychological disturbances at diagnosis, but over the following years depression and distress may become more frequent.

- Depression and Type 2 are closely linked.

- The best treatments are psychological and careful management of diabetes itself. Antidepressants don’t usually help unless there are other complications present.

- The cumulative burden of managing diabetes over many years can lead to distress, and finally to burnout.

- Sympathetic and careful medical management is probably the best way of tackling diabetes distress and burnout.

Diabetes and mental health

The highly complex relationship between the mind and Type 2 diabetes has been explored over many years, but most of the research articles are concerned with depression in diabetes. Depression is common in all types of diabetes, and at all ages, and as we’ll see, although it’s important, it is only one of several psychological problems encountered in diabetes. One of the reasons depression has been so much of a focus is that the severity of depression can be reliably measured using carefully standardised questionnaires and interview techniques. Not very long ago, as part of their contract, GPs in the UK were required to ask all people with diabetes to complete such a questionnaire, though I don’t think anything much of practical value resulted from the exercise.

Surprisingly little is known about the range of psychological disorders that don’t quite add up to depression, but which can be just as disruptive to the lives of people with Type 2. For example, ‘diabetes distress’, of which more shortly, is likely to cause more difficulty than full-blown depression. At the other end of the spectrum of severity, some organisations have gone so far as to consider the response to the diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes as similar to the response to a fatal diagnosis. You may know of the series of stages described by the famous psychologist, Elisabeth Kubler-Ross (denial, anger, bargaining, depression and acceptance) back in the late 1960s.

I think this is going much too far – Type 2 diabetes is hardly a fatal diagnosis after all – but Kubler-Ross’s scheme covers many of the factors experienced by newly diagnosed people. In addition, there may also be a sense of guilt, and if I developed Type 2 diabetes I suspect that would be my most powerful initial feeling: I had got my comeuppance after years of ‘bad’ habits. Diabetes is a disorder associated with weight (though, as we have seen, most people with diabetes are no more overweight than their peers without diabetes). This then ties in with eating patterns that may be seen as abnormal, though actually they’re probably no different from those of non-diabetic people either. But in my discussions with Type 2s, guilt is very common, and shows itself in all kinds of ways. For example: guilt that in some way the person has a self-inflicted condition; guilt that he/she isn’t doing what he/she has been told to bring it under control (especially diet and weight loss) and guilt about the consequences of a major long-term condition on his/her family.

Psychological symptoms at the time of diagnosis

Some of the elements in Kubler-Ross’s sequence are relevant when Type 2 is first diagnosed. Denial, for example, is probably present in many people with diabetes. Even if there are symptoms at the onset, they are usually due to high glucose levels (thirst, getting up in the night to go to the loo, blurred vision etc. – see Chapter 2) and don’t usually last long. Do I really have diabetes or is it just a period of funny symptoms that have now gone away of their own accord? If there has been any weight loss it may give rise to mixed feelings: perhaps that diet we’d promised ourselves is finally working, or a little more exercise is at last having some effect rather than it being a result of poorly controlled diabetes with high blood glucose levels.

Middle-aged people who lose a lot of weight quickly and for no apparent reason may well worry that there is cancer lurking, and once that has been excluded, then there may be some – temporary – sense of relief. I think everyone has a different mix of feelings at this stage of diabetes, and that’s because by the time we’re in our 40s or 50s, we all have very different lives, different work and family circumstances, and a variable medical history behind us. To return to feelings of guilt, professionals need to recognise that these feelings are often present, though not often articulated, and that this is definitely not the time to compound any guilt (actually no time is right for that). Sadly, this still occurs, though as our understanding of the complexity of Type 2 diabetes has developed over the past 30–40 years, we fortunately see this unhelpful blame-guilt cycle much less than before.

These varied responses aren’t always captured in the academic studies. Naturally, there is generally much less psychological upset when Type 2 is diagnosed than Type 1, which usually comes out of the blue in childhood, and requires massive and immediate life-changes to adapt quickly to permanent insulin treatment. But as we discussed in Chapter 2, a small number of people are first diagnosed with diabetes when they have an illness – for example, heart attack or stroke – that requires an emergency admission to hospital. I don’t think these patients have ever been studied to gauge the extent of their psychological disturbance.

Stress, work and diabetes

Perhaps the most common question at diabetes onset is: ‘Was it stress that brought it on?’ We know that in Type 1 diabetes, medical stress – for example, a major illness or hospitalisation – is more common in the year preceding the onset of diabetes than in people who don’t develop diabetes. Perhaps more interesting, major family disturbances – for example, parental separation or divorce in the previous year – also increase the risk of developing Type 1 diabetes. Type 2 is completely different. All the same, we know that some forms of stress, especially long-term stress at work, increase the risk of developing Type 2. (It also increases the risk of depression, which, as we’ll see, is strongly linked to Type 2.) The key factor here may be cortisol, the major hormone released from the adrenal glands near the kidneys during psychological and physical stress. Cortisol is well known to increase insulin resistance and predispose people to developing the metabolic syndrome (see Chapter 3). We can therefore see a close biological link between stress, cortisol and the development of Type 2, and there was great interest in developing drugs that could reduce the effects of cortisol. In early trials they significantly reduced blood glucose in people with Type 2. Interestingly, adrenaline, the ‘fight or flight’ hormone we all know is linked to stress, probably plays no part in the development of Type 2.

Key point: Long-term work stress is associated with an increased risk of developing Type 2 diabetes.

This is all very interesting, but is it of any practical value to pre-diabetic individuals or those with Type 2? There are no official studies of the effect of continuing stress at work on Type 2, but there are plenty of reasons why stressed workers might have poor blood glucose control (and for that matter, poor blood pressure control). You will see no great surprises in the list below, but have a think about factors that may operate for you and whether you can reduce them in your work life.

- Erratic meals, especially high-carbohydrate lunches wolfed down while gazing at a computer screen.

- Missing medication, especially a lunchtime dose of fast-acting insulin.

- Shift work is associated with increased risks of a range of conditions, including Type 2 diabetes, weight gain, coronary heart disease and stroke.

- Disturbed sleep patterns, associated with poor blood pressure control.

- Electronic stress – deluges of emails, in particular – is also likely to compromise blood pressure control.

- No time for work-associated activity; gym sessions postponed (see Chapter 8).

Key point: Analyse carefully what stresses you are exposed to in your workplace, and consider possible ways of reducing them.

Depression and Type 2

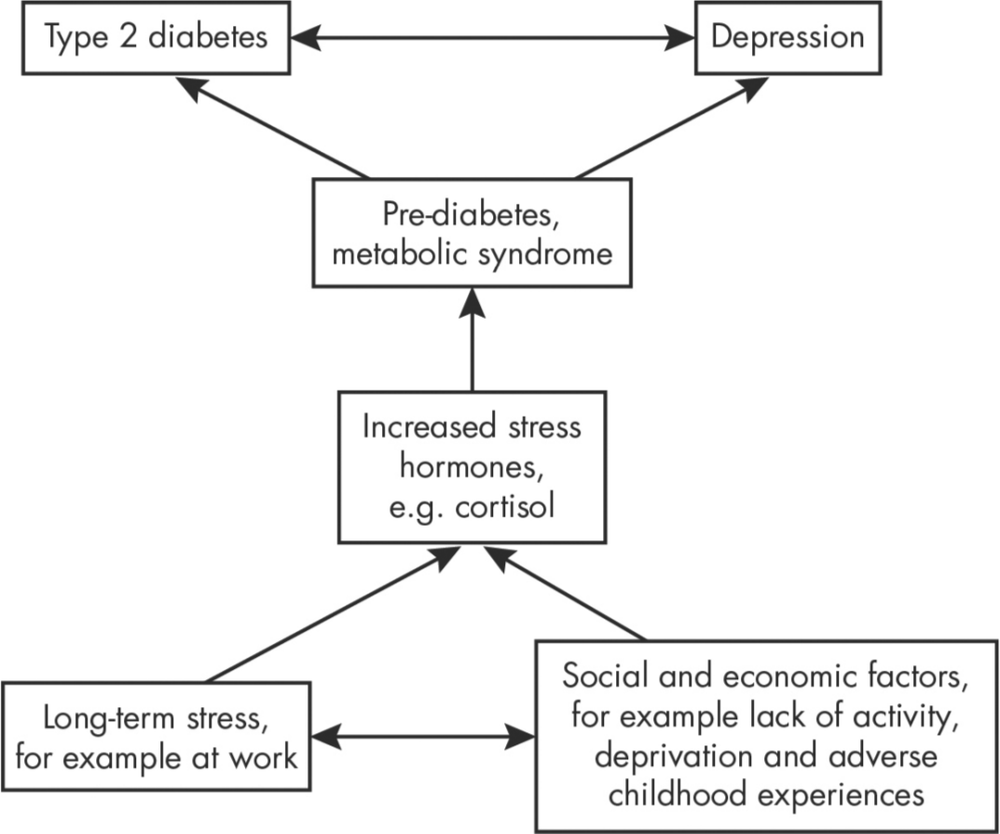

Since so much work has been done on Type 2 and depression, let’s summarise some of the current understanding. You might think the link is relatively simple. Type 2 is a long-term condition that requires continual self-management, is associated with a range of complications, and usually needs treatment with medication that can have side-effects. So, Type 2 diabetes can lead to depression. But it’s more complicated than that. While Type 2 is indeed associated with an increased risk of developing depressive symptoms, the converse is also true: people with depression have a higher risk of developing Type 2 diabetes. The reasons for depression leading to an increased risk of Type 2 aren’t known, but stress and stress hormones, especially cortisol, may predispose to depression. It’s an intriguing idea, and more research will no doubt emerge. Other hormones may be involved, including testosterone in men (and presumably abnormalities of sex hormones in females). If we take a broader view of these tentative ideas, we can see again a series of links that help us understand Type 2 diabetes as a whole-body problem, rather than as a limited condition just involving high blood glucose levels.

An even more linked-up explanation is that both Type 2 diabetes and depression share similar roots in psychosocial factors. For example, reduced activity levels, social deprivation and adverse conditions during childhood may contribute to both conditions (see Figure 13.1).

Figure 13.1: Some of the links between Type 2 diabetes, stresses during life and depression.

When depression occurs in Type 2, it is strongly associated with high blood pressure and medication for high blood pressure, being overweight, cigarette smoking, reduced physical ability to do exercise, and – most consistent of all – a greater likelihood of missing medical appointments. This last factor may well perpetuate the tendency to depression, as it is less likely to be diagnosed, intercepted and treated if people don’t attend appointments. But even where medical care is very good, consultations in both hospital clinics and general practice tend to be preoccupied with blood glucose control and helping people to improve it, and a possible major underlying problem, serious depression, may not come to light.

Key point: Type 2 diabetes can lead to depression, but more intriguingly depression itself increases the risk of developing Type 2.

Treatments for depression in people with Type 2

Because diabetes and depression occur so commonly together there have been several studies to try and find effective treatments. Ideal therapy would, of course, improve symptoms of depression, but could they also improve physical function? There is some evidence for this from the Look AHEAD study (see Chapter 5 and References on page 214), where people in the intensive lifestyle group had better muscle function and were also less likely to develop depression. Frequent and intensive collaborative medical care focused on physical aspects of poorly controlled diabetes improved blood glucose, cholesterol and blood pressure and – surprisingly – also improved depression scores. In other words it looks as if intensive medical input improves both physical and psychological health in Type 2.

Key point: Intensive medical treatment improves measures of diabetes, including blood glucose and blood pressure, and also psychological functioning, in Type 2 people with depression.

Psychological treatments

Psychological treatments have not been as thoroughly studied as medical treatment, but all types of therapy – for example, cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), mindfulness-based therapy, internet-based guided self-help – improve depression severity, but do not seem to improve the physical aspects of diabetes, including blood glucose control.

Antidepressants

Antidepressant medications might seem the obvious treatment, but they haven’t been thoroughly investigated in long-term conditions like diabetes, and, as we’ve seen, psychological treatments and interventions focused on the diabetes itself are at least as effective. However, one trial found that if people choose antidepressant treatment and if symptoms improve in the first three months, then medication seems to be beneficial if it’s continued. People who have both medical complications of diabetes and depression also respond well to medically orientated treatment and antidepressants. As in all areas of diabetes, the key is to select treatments that are most likely to help individuals with particular problems. Regardless of the treatment, the organisation of care – for example, how often you go for psychological treatment, and the type and dose of drug – must be properly planned and implemented and based on clinical trial protocols. A bit of extra medical input or one psychological appointment is unlikely to be of much use.

Diabetes distress

A distress response to diabetes is not a psychiatric disorder, such as depression, but is very common, perhaps occurring in nearly 50% of Type 2s. Broadly, it’s the stress response (note, stress again) to living with a complex and long-term condition. Its main components won’t come as a surprise:

- the demands of self-care leading to anger and frustration

- concern about an uncertain future with diabetes, and the possibility of complications

- concern about the quality of care

- perceived lack of support from family and friends.

There have been many studies on distress and its management, but in practice even those with quite severe depression may not be able to access optimum treatment, so informal management of distress falls to family, colleagues and the healthcare team. We saw that careful and attentive medical care improves depressive symptoms and standard indicators of diabetes (HbA1c, blood pressure and cholesterol). Distress is often focused around practical considerations (for example, large amounts of medication, injections, excessive requirements for blood glucose testing). Doctors are often not sensitive enough to the adverse impact of people’s day-to-day concerns about diabetes, nor the burden of longer-term concerns.

Diabetes burnout

Diabetes burnout is a widely used term, and very valuable. It conveys a vivid and immediate picture of someone with diabetes eventually exhausted by the stresses of maintaining ‘good’ glucose control, while also having to deal with family, the workplace (where the term ‘burnout’ originated). and the countless other day-to-day problems that compete for limited mental space. Online diabetes communities are full of discussions about this evidently common problem, but out of millions of medical articles I could only find a couple that referred to it. This itself is a significant observation: here’s something that everyone is talking about electronically, yet it doesn’t seem to be recognised by the medical world. We urgently need a proper definition, but until then let’s think of a burnt-out person with diabetes as someone who has lived with it for a number of years, taking an ever-increasing amount of medication, perhaps who has accumulated a few complications requiring additional medical care and more frequent clinic appointments, and whose family and friends are themselves stressed with the burden of living with someone who has a long-term condition.

There are many different scenarios of burnout. I’ve often seen it in Type 1 and 2 people who are trying to maintain unrealistic and unhelpful ‘normal’ blood glucose levels; they end up doing countless finger-prick blood glucose levels and eventually, of course, become depressed and stressed by the effort and – worse – usually don’t manage to achieve the unachievable. This spills over into relationship problems with friends and family, and risks further spread of conflict and anxiety. The fault here sometimes lies with healthcare professionals, who impose arbitrary blood glucose limits and then don’t always support their patients to achieve them. In Type 2 I see a different variety, ‘diet burnout’. Again this often results from arbitrary and unnecessary food restrictions, often of the ‘you mustn’t eat cake’ variety. These impositions often date from many years ago, but they are alive and kicking today and perhaps even more dogmatic: think how many times you’ve seen internet ads for ‘10 foods you must [or must not] eat in order to reduce your belly fat’ or similar.

One approach to burnout is to minimise practical burdens.

- Can we realistically reduce medication and excessive self-monitoring? (This was explored in Chapter 7, and discussed in relation to older people in Chapter 12.)

- Closely related: request a detailed medication review with your diabetes team or specialist pharmacist with the aim of rationalising and simplifying your drug treatment if possible. Why were they prescribed in the first place (it’s often surprising that nobody – doctor or Type 2 – can remember why), and are they needed now? (See Chapter 7.)

These are the ‘medical’ approaches. Others may be needed. If you are also depressed as a result of burnout, then that needs managing as well (though, as we’ve seen, one of the best ways of managing depression in Type 2 is to refine the condition’s medical treatment). Many people will go online for information and advice, and perhaps join a forum. It’s not known how effective they are, but advice is usually sound. The small amount of irresponsible content is usually weeded out when groups of people with a shared problem are communicating with each other. Because people with Type 2 can experience a range of potentially very serious problems, some have a tendency to catastrophise – that is, imagine that they will run into a never-ending series of disabling complications. We know that any major consequences of Type 2 are not that common, and becoming less so with time, so establishing a relationship with a healthcare professional who has a realistic understanding of diabetes in the long term can be genuinely reassuring to many people.

Summary

Psychological problems are very common in Type 2 diabetes. Stress, especially at work, is a recurrent theme, and it probably increases the risk of developing Type 2. Depression also increases the risk of developing diabetes, which is less intuitive than Type 2 increasing the risk of depression. Psychological therapies are probably more effective than antidepressant medication. Again not intuitively, diabetes and depression both improve after intensive medical supervision. Diabetes distress is very common and is related in part to the practical demands of this complicated condition (for example, the medication burden).