Table 2.1 Themes in IC research

Source: Adapted from Mouritsen (2006, p. 824)

p.21

THE CRITICAL PATH OF INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL

John Dumay, James Guthrie, and Jim Rooney

Introduction

This chapter examines the path that critical intellectual capital (IC) research has followed from its early days before and just after the new millennium, to where it stands in contemporary times. Understanding the path critical IC research is taking is essential because IC researchers need to know where others have travelled before embarking or reflecting on their own journey. Contemporary IC research has four stages. The first stage is raising awareness. The second stage is theory building and frameworks (Petty and Guthrie, 2000). The third stage is investigating IC in practice from a critical and performative perspective (Guthrie et al., 2012, p. 69). A fourth stage is an ecosystem approach as outlined by Dumay and Garanina, 2013. These stages are the foundation of the critical path of IC.

IC is an interesting concept, but along with its espoused benefits, the concepts behind IC need to be questioned so that IC research and practice can progress (Dumay, 2012). This chapter shows how critical IC research continues to develop. First, it considers IC as a general concept, asking the question: what is intellectual capital? Defining IC is important because, like any common term, we need to know the context in which it is used. As Pike et al. (2006, p. 233) outline, a major obstacle when talking about IC is that there is no single agreed definition, and thus the first section explores three different, and useful, IC definitions.

Second, the chapter outlines the early critical paths found in the work of Sveiby (2007) and two special issues of the Journal of Intellectual Capital (JIC) by Chatzkel (2004) and O‘Donnell et al. (2006a). Sveiby (2007), was especially critical of measuring intangibles and using them for management control and public relations purposes. Sveiby’s criticisum is echoed in Chatzkel’s (2004) argument that IC was at a crossroads of relevance and IC research needed to be critical to help make IC work, as it was in danger of fading away into insignificance.

Third, the chapter outlines the critical and performative practice turn in IC research. The original turning point is arguably an article by Jan Mouritsen (2006), which introduces a different way of thinking about IC based on the work of Latour (1986), using the dichotomy of ostensive versus performative IC. Later, a special issue of the journal Critical Perspectives on Accounting critically examined IC measurement (Mouritsen and Roslender, 2009). Understanding the purpose of measuring IC is important because otherwise it might be used counterproductively. As Gowthorpe (2009, p. 830) aptly outlines “it is more likely the case that IC metrics will be interpreted in some quarters as offering new and exciting ways to bully people”. From a different perspective, Dumay (2009a, p. 206) examines how IC is measured in contrast to the ‘accountingization’ of IC, leading to a more productive way of understanding IC.

p.22

Additionally, this section outlines how the outcomes of critical management studies, being insight, critique and transformative redefinition, are a useful way of examining IC from a critical perspective. Based on the work of Alvesson and Deetz (2000), Dumay (2008a) justifies a critical analysis of IC in action because IC development parallels critical theory, that is, it is in response to changing social conditions in “science, industrialization and communication/information technologies” (Alvesson and Deetz, 2000, p. 14). Similarly, IC came into prominence because of structural economic changes as knowledge, communication, and the importance of intangibles changed the way organizations operate (Meritum Project, 2002).

The chapter then examines what Guthrie et al. (2012) brand third stage IC research. Inspired by Mouritsen’s (2006) ostensive versus performative IC theorization, Guthrie et al. (2012, p. 69) outline how IC “research is emerging based on a critical and performative analysis of IC practices in action”. The Guthrie et al. (2012) article is important because its conclusion, which opens the opportunity for more research examining IC practices, has largely come to fruition. For example, a special issue of the JIC examining the IC third stage followed shortly after their article was published (Dumay, 2013), as did many other articles based on third stage IC research, making Guthrie et al. (2012) the most highly cited IC article since 2012.

A fourth section emanates from another important outcome of the IC third stage special issue, that is Dumay and Garanina’s (2013) critical examination of the emergent third stage research. Their conclusion (p. 21) outlines the prospect of a fourth stage of IC research, which:

[s]hifts the focus of IC within a firm to a longitudinal focus of how IC is utilized to navigate the knowledge created by countries, cities and communities and advocates how knowledge can be widely developed thus switching from a managerial to an eco-system focus.

The fourth stage has its roots in critical social and environmental accounting (Gray, 2006), and despite being not a theoretically new concept, has inspired an alternate form of IC research.

To conclude, the dominance of the managerial approach to IC is discussed, along with an examination of the possibilty that the wealth creation, rather than value creation, mantra is having a resurgence (International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), 2013; Lev and Gu, 2016) and that after losing its momentum a decade ago (Dumay, 2016), IC reporting may be once more attracting attention. However, this resurgence may be short lived if the focus is only on investors and managers – it is no longer responsible for companies to put profits before people and the environment. Therefore, more research is needed to understand how IC helps develop value beyond organizational boundaries.

Going beyond organizational boundaries also requires IC researchers to broaden their approach to IC because it is currently too narrow and disjointed. Currently, the term ‘intellectual capital’ is not in regular use in business and the term ‘intangible assets’ is more common (Cuozzo et al., 2017). Additionally, current IC research mainly ignores the US and focuses on European academic journals, demonstrating the narrowness of IC as a research field. Broadening IC research will raise awarness and expand the potential of IC research.

p.23

What is IC?

Defining IC is important because, like any common term, we need to know the context in which we use it. As Pike et al. (2006, p. 233) outline, a major obstacle when talking about IC is that there is no single agreed definition. However, in this book (Guthrie et al., 2017), most authors would refer to at least three common elements being human, structural, and relational capital, which has its origins in the Skandia Navigator model proposed by Leif Edvinsson in the early 1990s (Skandia, 1994). While the three IC elements help us classify different types of IC, it is by no means a definition.

Usually, when defining a term like ‘intellectual capital’, is it best to break it into separate components and then join the definitions together. As a noun, intellectual means a person having a high degree of intellect, while as an adjective, it relates to the intellect of a person or within an object. As for capital, when used as an adjective it relates to the principal assets used in business to create wealth. Thus, when putting these terms together, IC is the sum of the principal intellectual assets within a business used to create wealth. Hence, it is not surprising that people use the term IC synonymously with the terms intangible assets, intellectual assets, and intangibles (Eccles and Krzus, 2010).

The above definition is closely related to one of the original IC definitions by Thomas Stewart, a Forbes Magazine journalist in the 1990s, who wrote one of the first seminal books about IC (Stewart, 1997, p. x): “the sum of everything everybody in a company knows that gives it a competitive edge . . . Intellectual Capital is intellectual material, knowledge, experience, intellectual property, information . . . that can be put to use to create wealth”.

However, Dumay (2016) replaces the word ‘wealth’ with the word ‘value’ for two reasons. First, most IC researchers, practitioners, and authors refer to ‘value creation’, rather than ‘wealth creation’ (Mouritsen et al., 2001a). Second, in today’s society, organizations can no longer just focus on creating wealth because they must also concentrate on creating useful products and services, while at the same time contributing to society and not destroying the environment. These are what Dumay (2016) refers to as utility, and social and environmental value in conjunction with economic value.

The focus on economic value has also led to another IC definition based on the difference between the market and book values of a company. The advantage of this definition is that it provides a simple means of putting a monetary value on IC. However, it does not break down IC into its components and is subject to change on a regular basis, and thus is an unreliable measure (Dumay, 2012).

Additionally, Pike et al. (2006, p. 233) offer a third IC definition being “a holistic management methodology”. Here, IC is part of a management philosophy that places IC within the boundary of the entire company. Pike et al. (2006) base their definition on the resource-based-view (RBV) of the firm, which recognizes the interaction of a combination of resources as being core to the development of competitive advantage and economic value (Barney, 1991). However, the RBV creates as many questions as it does answers because there is causal ambiguity relating to the difficulty in identifying the correct resources to accumulate and the inability to control them (e.g. human resources) (Dierickx and Cool, 1989, p. 1509). Therefore, a holistic management approach, which is uncritical of IC, may not offer a complete definition of IC because the philosophy does not expand beyond the boundaries of the firm.

IC and its early critical path

As evidenced above, IC has different definitions because people have different philosophical ideas about IC and its purpose. In the early days of IC, the writings of Stewart (1991), Edvinsson and Malone (1997), and Roos et al. (1997) helped to “render invisible visible by creating a discourse that all could engage in” (Petty and Guthrie, 2000, p. 156). This ‘first stage’ of IC research was firmly established by the turn of the millennium and the second stage emerged to establish IC’s legitimacy and to promote its further development (Petty and Guthrie, 2000). However, rendering the invisible visible in the second stage proved to be problematic because people also then wanted to ascribe a dollar value to IC. But how can you measure something that does not exist?

p.24

Sveiby’s criticisms

One of the first people to become critical of measuring IC or intangibles was Karl-Erik Sveiby, who set up a webpage in 2004 warning of the potential problems associated with measuring IC and continued to update the webpage for several years (Sveiby, 2010). Sveiby had three critical messages based upon what he called the “fundamental dilemma” of measuring intangibles “because it is not possible to measure social phenomena with anything close to scientific accuracy”. First, he warned against the use of IC measures for management control purposes – as most employees react negatively to being measured, people would attempt to game the new system for their benefit. Similarly, Gowthorpe (2009) outlines that measuring IC may end up being just another interesting way to bully people rather than a way to understand and create value.

Additionally, using imprecise intangible measures could lead to producing unintended results. Kerr (1995, p. 7) argues that the behaviour rewarded is often the undesired behaviour, while the desired behaviour is not. Sveiby (2010) uses the example of Royal Dutch Shell, the managers of which in the late 1990s were rewarded for increasing the oil reserves under the company’s control – unsurprisingly the reserves increased. However, in 2004, Shell was embarrassed to disclose that the managers were systemically overstating the reserves and had to adjust down previously disclosed reserves by 23 per cent. Shell fired the managers, but Sveiby (2010) lays the blame not just on the managers but also on the reward system (see also, Kerr, 1995).

Second, Sveiby (2010) warns against using IC reporting as a public relations exercise. For example, Swedish insurance company Skandia was famous for publishing the world’s first external IC statement and was not shy about publicising its value creation story in subsequent IC supplements (Skandia, 1994, 1995, 1996, 1998). However, can a company always rely on its IC? As Sveiby (2010) observes, “those who bought Skandia shares based on their IC supplements back then were looking at losses amounting to 90% in 2002” as sales and profits fell sharply (Dumay, 2012). However, when Dumay (2016, pp. 170–171) interviewed Skandia’s former chief IC architect, Leif Edvinsson, in 2012, a discussion ensued about the reasons for Skandia’s demise, where Edvinsson disclosed:

So there was a lot of financial muscle and market muscle and a lot of old customer value in it, and millions of customer relationships, which you could leverage if you renewed the organisation rather than doing the opposite saying “OK let’s start to harvest!” They didn’t actually say that but behaved that way. So they looked at the balance sheet and saw that “Wow, we can sell off!” … then they stripped the organisation of its velocity.

Thus, while Skandia made use of public relations to develop its business in the 1990s, it was switching to harvesting cash from the business and the subsequent lack of focus on IC led to its eventual demise. The executive managers did such a good job of harvesting cash that it eventually led to criminal fraud investigations1 and the then CEO, Lars-Eric Petersson, was convicted of fraud and sentenced to two years jail for giving 156 million kronor ($21.4 million) in bonuses to company executives without board approval.2

p.25

Third, Sveiby (2010) advocates that IC should be used solely to help companies and their people learn. He argues that measuring intangibles and IC helps companies become more efficient by uncovering costs and giving them the opportunity to explore other value creation activities. However, Sveiby (2010) does admit that there is a fine line between management control and learning and advocates producing bottom-up, self-directed, open, and comparable metrics that are used to reward groups, rather than individual employees.

Critical accounting scholarship

While Sveiby was criticizing IC from a measurement perspective, a substantive critique of IC was also emerging from articles published by critical scholars in the Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal (AAAJ) in 2001 as well as the JIC in two special issues in 2004 by Marr and Chatzkel (2004) and 2006 by O’Donnell et al. (2006a). Each of these special issues is discussed next.

Sunrise in the knowledge economy: managing, measuring, and reporting IC

The first critical special issue was published in AAAJ in 2001 (Vol. 14 Issue 1). In the opening to the special issue, Guthrie et al. (2001, p. 365) outline “that critical and social accounting academics have a vital role to play in making visible a number of important social issues that stem from understanding better the value of IC within both organisations and the wider social fabric”.

The prominent critical article in the special issue is by Roslender and Fincham (2001, p. 383), who examine the debate about IC accounting for reporting and managerial purposes versus IC providing its own accounts, “rather than remaining imprisoned within accounts devised by others”. Their criticism of accounting includes discussion of whether the purpose of financial accounting is to provide a historical view of accounting transactions, rather than using financial accounting to explain how market values are derived (Roslender and Fincham, 2001, pp. 387–390). In its place Roslender and Fincham (2001, p. 393) argue that we should be more concerned with how IC “might account for itself” through IC reporting.

While Roslender and Fincham (2001) examine reporting as a solution, other authors also investigate the then newfound interest in IC reporting as it was emerging from the perspective of early adopter Skandia (Mouritsen et al., 2001b), from Ireland (Brennan, 2001), and reporting in general (Van Der Meer-Kooistra and Zijlstra, 2001). While these authors critically examine IC reporting, most do not sway from recommending that IC reporting should complement financial accounting and help to develop “the building blocks of an IC reporting model” (Van Der Meer-Kooistra and Zijlstra, 2001, p. 456).

Other critical articles investigate the accounting treatment of goodwill and intangible assets (Stolowy and Jeny-Cazavan, 2001), the value of IC in the police force (Collier, 2001), and IC from a financial institution and corporate governance perspective (Holland, 2001). As evidenced by these and the previously discusssed articles, the special issue offers an early insight into IC just after it became a hot topic, and helped to stimulate further critical IC research by opening up research questions based on the realm of IC, the spread of IC measurement, organizational fit, the role of information and communications technology, and the costs and benefits of IC. The latter costs and benefits proved an instrumental question as they are at the heart of the debate about IC theory (Dumay, 2012), and are a major topic in the first JIC critical IC special issue edited by Chatzkel (2004).

p.26

IC at a crossroads: becoming critical of IC

The first JIC special issue, “IC at the crossroads: Theory and research” examines research after the importance of IC had already been established (Petty and Guthrie’s (2000) first stage). The special issue examines IC measurement (Andriessen, 2004; Grasenick and Low, 2004; Pike and Roos, 2004), theory (Mouritsen, 2004; O’Donnell, 2004) and research methods (Guthrie et al., 2004; Marr et al., 2004), and its application to e-commerce (Bakhru, 2004). Thus, these papers began to critically examine how IC is measured, theorized, researched, and applied, rather than just providing normative arguments about why IC is important.

The last article in the special issue by Jay Chatzkel (2004) outlines how IC was at a crossroads of relevance because IC was transitioning to its next stage. Chatzkel (2004) also argues that IC needed to transform into a working discipline, rather than a theoretical one, that was useful to organizations for achieving strategic outcomes. Furthermore, Chatzkel (2004, p. 337) outlines how IC needed to move forward as a discipline, otherwise “the notion of intellectual capital and all it stands for will be seen as merely one more set of very interesting ideas that is continuingly elusive to grasp and use”. Thus, IC was a stage where it needed to break free from being a management fad or fashion, and become an established management tool (Serenko and Bontis, 2013, p. 477).

Becoming critical on IC

The Chatzkel (2004) article then helped inspire the second special issue by O’Donnell et al. (2006a) entitled “Becoming critical on intellectual capital”. As O’Donnell et al. (2006a, p. 5) outline, “IC is at a ‘crossroads’; one of these roads takes a critical stance and the purpose of both the CMS stream and this special issue is to initiate some exploratory discourse on IC from this perspective”. The special issue emanates from papers presented during the IC Stream at the 4th International Critical Management Studies Conference at Cambridge University, UK, in July 2005. Most importantly, this JIC special issue sought understanding of how “IC could make a difference for the better” (O’Donnell et al., 2006a).

To frame the special issue, O’Donnell et al. (2006a, p. 6) introduces a critical management studies perspective, which “addresses a wide range of issues that extend from diversity to globalization, from labour process to philosophy, from technology to sexuality and gender”. The special issue is a collection of articles from differing perspectives critiquing IC based on philosophy (Chaharbaghi and Cripps, 2006; Spender, 2006), innovation (Voepel et al., 2006), research (Abeysekera, 2006), language (Andriessen, 2006; Jørgensen, 2006), and labour (O’Donnell et al., 2006b). To conclude the special issue, O’Donnell et al. (2006a, p. 6) ascertains that the articles “present a provocative range of perspectives that need to be taken into account as we move across through our threshold and onto the next stage of intellectual capital”.

On reviewing the articles presented, it is evident that they do present a provocative perspective on IC. For example, the Chaharbaghi and Cripps (2006) article, “Intellectual capital: Direction, not blind faith” challenges the very foundations of the first stage of IC. They argue that IC is not reducible to a number that indicates increases or decreases in an organization’s IC. Rather, IC is fluid and indicators represent the direction “imagination, creativity and learning” is taking (Chaharbaghi and Cripps, 2006, p. 29). In support, Victor Newman, whose commentary at the end of the article outlines how two ideas presented in Thomas Stewart’s seminal book Intellectual Capital (Stewart, 1997) – that IC can be managed similarly to physical assets and investing in knowledge helps create monetary wealth – are unproven assumptions (Chaharbaghi and Cripps, 2006, p. 42). In support, Dumay (2012) later argues that these assumptions are akin to unsubstantiated IC grand theories, which are barriers to implementing IC practices, rather than enablers of IC practice. Thus, the O’Donnell et al. (2006a) special issue came at a time where the foundations of IC were on shaky ground and outlined that a more critical path to IC was needed for it to progress beyond being just an interesting idea based on unproven assumptions.

p.27

The critical and performative practice turn

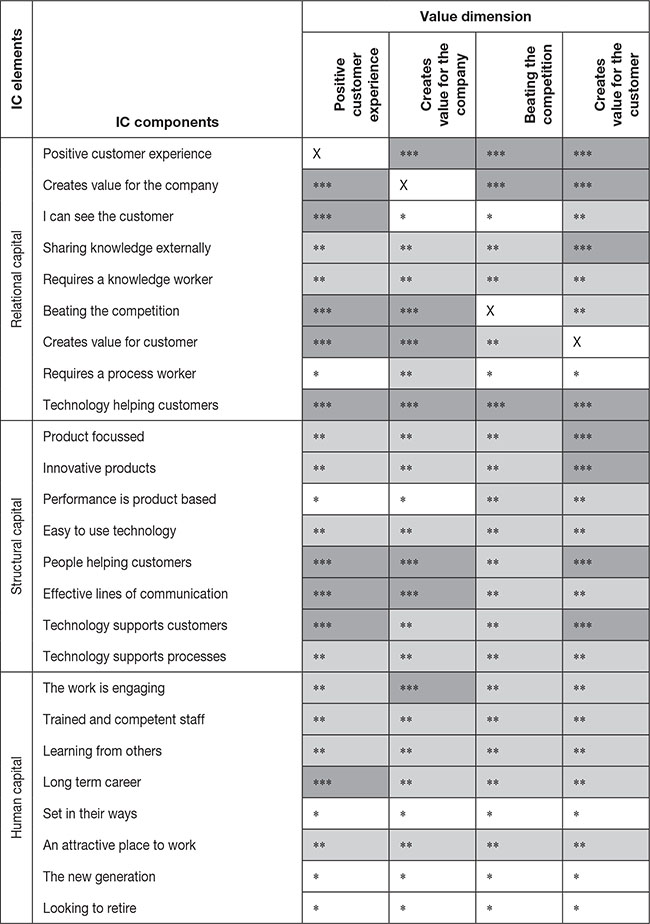

The next stage of IC thinking is now commonly known as the third stage, testing IC’s ideology and assumptions (Guthrie et al., 2012) and taking what Guthrie and Dumay (2015, p. 260) call the “practice turn”. The original turning point is arguably an article by Mouritsen (2006), which introduces a different way of thinking about IC based on the work of Latour (1986), using the dichotomy of ostensive versus performative IC, or as Mouritsen labels it, IC1 and IC2 (Table 2.1). Put simply, ostensive relates to the IC ‘big picture’, attempting to make a predictable link to creating value. In contrast, performative is how IC works in organizations and society where knowledge transforms and is valuable because it accomplishes something.

The distinction between IC helping create value or being valued is an important philosophical difference. It questions whether managing IC makes an organization worth more, as Stewart and Losee (1994) and Skandia (1995) claimed in the 1990s. Thus, the third stage focused on whether IC could make a difference, rather than just make companies and their shareholders wealthier.

p.28

Critical IC

The view that measuring and accounting for IC, and that IC should be included on the balance sheet and thus needed managing to benefit financial capital, was well entrenched by 2005 (Fincham et al., 2005). Thus, the time was ripe for a more critical examination of IC because the class that gives intellect “to intellectual capital – labour – finds itself subordinate to capital” (Fincham et al., 2005, p. 351). This view led to another special issue on IC, this time in the journal Critical Perspectives on Accounting (CPA) in 2009 (Mouritsen and Roslender, 2009).

What emerges from this special issue is a continuing concern about the ethics of IC as a management technology. As Mouritsen and Roslender (2009, p. 802) outline, the concern raises two questions: ‘does the measurement of knowledge (resources) produce effects; and is the concern to inscribe the person in the intellectual capital statement an act of appropriation which raises ethical concerns?’ The papers in this CPA special issue challenge the accounting foundations of IC by examining calculation (Mårtensson, 2009), numbering (McPhail, 2009), reporting (Nielsen and Madsen, 2009), quantification (Gowthorpe, 2009), and measuring people (Roslender and Stevenson, 2009).

To conclude the special issue, Mouritsen and Roslender (2009, p. 803) outline how researchers and managers still struggle with accounting for IC to the point that scholars are “unquestioning” of IC, and muse that IC accounting has become part of the mainstream. Mouritsen and Roslender (2009, p. 803) argue that the papers in the special issue demonstrate how it is beneficial to take a more critical perspective towards IC to ensure it is useful for the betterment of society, and not just to take advantage of people for the sake of creating monetary wealth.

IC measurement: a critical approach

While Mouritsen and Roslender were developing their CPA special issue, a then Australian PhD student, John Dumay, was writing his thesis (Dumay, 2008a) based on IC in action and partly inspired by Mouritsen’s (2006) ostensive versus performative IC agenda. In the thesis, Dumay included four published articles, which examine “How is IC?” rather than “What is IC?” (Dumay and Tull, 2007; Dumay, 2008b, 2009a, 2009b). Of the four articles in the thesis, arguably an important paper is “Intellectual capital measurement: A critical approach” (Dumay, 2009a), which is the most cited of the articles.3

Dumay (2009a) is important because it introduces complexity theory into IC research to help reduce the causal ambiguity problem (Dierickx and Cool, 1989) surrounding IC’s ability to accomplish something. In considering how IC can be measured, Dumay (2009a) applies complexity theory because it deals with understanding systems exhibiting non-linear relationships between the elements of the system and is characterized by the observation that small changes to one or two parameters have significant, emerging, and unexpected effects on the system as a whole (Snowden and Boone, 2007). In his research Dumay (2009a) views organizations as complex systems. and by applying complexity theory-based research methods he develops different insights into IC, which may not be discovered using the then contemporary IC measurement and research frameworks. As Dumay (2009a) highlights, using both numbers and narratives shows how researchers can make sense of the complex interactions between IC resources contributing to value creation and thus reduce the causal ambiguity of intangible resources (Dierickx and Cool, 1989, pp. 1508–1509).

p.29

Figure 2.1 Value dimensions and inter-actions with IC components

Source: Adapted from Dumay (2009a, p. 202)

p.30

To do so, Dumay (2009a) presents visual maps of IC interactions showing how different elements of IC interact to create value. In Figure 2.1, the dark squares indicate a strong relationship between an IC element (rows) and a value dimension (columns). In this case, he shows how structural and relational capital is needed more than human capital to create value, which goes against the common belief that human capital is the most important. Identifying what IC elements create value in specific cases allows for more effective IC management because the analysis diminishes the ambiguity surrounding value creation.

While the Dumay (2009a) article is important because it addresses the causal ambiguity problem, he also uses a critical management framework to analyse IC research based on the work of Alvesson and Deetz (2000).

Critical management studies as an analytical framework

A notable analytical feature in the Dumay (2009a) articles is inspired by the writing of Alvesson and Deetz (2000) in their book Doing Critical Management Research. The analysis is not original to the above article and first appeared in the conclusion section of Dumay (2008b) and later in his thesis of the same year (Dumay, 2008a). Dumay (2008a) justifies a critical analysis of IC in action because IC development parallels critical theory. Alvesson and Deetz (2000, p. 14) outline how critical theory is a response to changing social conditions in “science, industrialization and communication/information technologies”. Similarly, IC came into prominence because of structural economic changes as knowledge, communication, and the importance of intangibles changed the way organizations now operate (Meritum Project, 2002). However, while most IC researchers promote the positive impacts of IC, the changes can also have negative impacts (e.g. Caddy, 2000; Leitner and O’Donnell, 2007).

Utilizing critique to examine IC transcends finding fault with IC by developing insights that identify and challenge the manner in which IC theory translates into practice. Examining contemporary theoretical IC frameworks is important because early academic research concentrated on establishing definitions, measures, and a proliferation of IC frameworks (e.g. Chatzkel, 2004; Sveiby, 2007; Guthrie et al., 2012). Additionally, at that time, IC suffered from a lack of practice as evidenced by the relatively few organizations that systematically disclose their IC (e.g. Brennan, 2001; April et al., 2003; Bontis, 2003; Ordóñez de Pablos, 2003; Guthrie et al., 2006; Unerman et al., 2007), which arguably continues to date (Dumay, 2016). Thus, a framework is needed to analyse what IC is (insight), to critique its application, and to offer new ways forward (transformative redefinition).

According to Alvesson and Deetz (2000, p. 17), the task of ‘insight’ is to demonstrate “our commitment to the hermeneutic, interpretive and ethnographic goals of local understandings closely connected to and appreciative of the lives of real people in real situations”. So, insight from a critical IC perspective involves trying to understand the impact of IC practices on both the people and their organizations. Thus, the question is not ‘What is intellectual capital?’ but ‘How is intellectual capital?’ (O’Donnell et al., 2006a, p. 7).

The objective of critique “is to counteract the dominance of taken-for-granted goals, ideas, ideologies, and discourses which put their imprints on management and organization phenomena” (Alvesson and Deetz, 2000, p. 18). Arguably, a critique of IC is important because of the development of contemporary IC terminology and ideas from traditional management thinking. The most prominent relates to the term ‘intellectual capital’, which leads to a misunderstanding of the nature of IC. For example, the word capital implies that knowledge is a form of material wealth to be managed like physical assets and that investing in these assets leads to the creation and possession of knowledge, resulting in more wealth, both of which are empirically unproven (Newman as quoted in Chaharbaghi and Cripps, 2006, p. 42). Thus, it is necessary to critique existing IC theories to understand whether they apply or are barriers to implementing in practice (Dumay, 2012).

p.31

The last task of this critical perspective “is the development of critical, managerially relevant knowledge and practical understandings that enable change and provide skills for new ways of operating” (Alvesson and Deetz, 2000, p. 19). This task is important for managing an organization’s IC because of the inherent contradictions in IC’s espoused benefits and the reality of organizational practices (Dumay, 2012). For example, as Mouritsen (2006, pp. 835–836) points out, organizations are more likely to invest in human capital when they are ‘in the black’ and to reduce the number of employees when they are ‘in the red’. Reducing employees in lean times contradicts the espoused benefits of human capital, which advocates the need to invest in employees because investing in human capital is beneficial for long-term wealth generation. These and other contradictions will continue to evolve from ongoing IC research and are opportunities to develop IC research into future management practices (see Alvesson and Deetz, 2000, p. 20).

Introducing third stage IC research

An important turning point in IC research is the Guthrie et al. (2012) article reviewing a decade of IC accounting research, introducing the third stage of IC research. The analysis in this article uses Mouritsen’s (2006) ostensive versus performative IC theorization to outline how “research is emerging based on a critical and performative analysis of IC practices in action” (Guthrie et al., 2012, p. 69). Their conclusion, based on finding that much of the past research into IC was commentary and normative policy rather than empirical papers, opens the opportunity for more research examining IC practices. As Guthrie et al. (2012, p. 79) emphasize:

We must challenge the status quo, employ innovative methodologies, experiment with the novel and take risks. We encourage you to watch the ICA space in the next decade for more critical field studies which will provide empirical studies of IC in action and help develop broader theoretical research.

Since the Guthrie et al. (2012) article was published, it has inspired many IC researchers to follow the critical and performative path. Thus the article is the most influential IC article published since 2012. For example, the article is heavily cited4 and was a winner of a prestigious Emerald Citations of Excellence Award5 in 2015. While the call for performative research became prominent after the paper’s publication, there is still a strong interest in ostensive IC research that examines IC’s causal effect on organizational performance (e.g. Joshi et al., 2013). However, evidence of how important the critical perspective is to IC researchers is the large number of articles and growing number of citations that critical IC research is now receiving (e.g. Dumay, 2012; Dumay and Garanina, 2013; Edvinsson, 2013; Iazzolino and Laise, 2013). Additionally, the IC third stage was the topic of another special issue of the JIC (Vol. 14 Issue 1), in the following year (Dumay, 2013).

This JIC special issue called for case studies and/or reflections of how organizations have implemented IC in practice and what they learned from it and encouraged articles from academics and practitioners who have got their ‘hands dirty’ by working in or with organizations that have mobilized IC in practice. In response, the JIC special issue published articles critically examining innovation (Yu and Humphreys, 2013), IC in action (Giuliani, 2013), SMEs (Henry, 2013), sustainability (Wasiluk, 2013), and education (Oliver, 2013), but most importantly, included two articles that use an interventionist approach to IC research (Chiucchi, 2013; Demartini and Paoloni, 2013). The latter two articles are important because they demonstrate how academic researchers can develop critical insights into IC practice by working alongside managers to solve real-life problems, rather than just observe practices. Using interventionist research also helps bridge the gap between academia and practice because it allows for the testing of IC theory, and makes a practical and academic contribution (Jönsson and Lukka, 2007; Dumay, 2010; Dumay and Baard, 2017). In essence, these articles demonstrate how academics got their ‘hands dirty’ working with organizations implementing IC practices.

p.32

This JIC special issue also contains two commentary articles by Dumay (2013) and Edvinsson (2013), which openly question the future of IC. Most notably, Edvinsson (2013, p. 163) reflects on 21 years of IC research and laments, “We need to go beyond IC reporting. We are on the edge of something, but what?” In answering “What?”, Edvinsson (2013) advocates expanding the boundaries of IC to include nations and society in general and to think of IC as more of a “strategic ecosystem for sustainable value creation”. In the same special issue, the conclusion to Dumay and Garanina’s (2013, p. 21) literature review of third stage research identifies the fourth stage of IC research, which:

[s]hifts the focus of IC within a firm to a longitudinal focus of how IC is utilized to navigate the knowledge created by countries, cities and communities and advocates how knowledge can be widely developed thus switching from a managerial to an eco-system focus.6

Thus, one way forward for IC is to remove the boundaries that lock IC into an inward looking managerial and organizational focus (see also, Gowthorpe, 2009). Therefore, another critical approach based on the impact of IC on the wider ecosystem has evolved and is discussed next.

Fourth stage IC research: an ecosystem approach

While the idea of an IC research fourth stage first appears in Dumay and Garanina (2013, p. 21), its roots are in social and environmental accounting inspired by Gray’s (2006) article “Social, environmental and sustainability reporting and organisational value creation?: Whose value? Whose creation?” In the article, referred to by Gray (2006, p. 793) as an ‘essay’, he challenges the role of social, environmental, and sustainability accounting and reporting, asking whether it should contribute to shareholder value and critiques the term value from a financial accounting perspective. Gray (2006, pp. 804–805) refers to three different approaches: managerialist, triple-bottom-line, and an ecological and ecojustice approach. Looking at the IC third stage, arguably it equates to a managerialist perspective because it is company-based and voluntary whereby IC is selectively managed, and it is assumed there is no conflict between economic value creation and the society in which the organization operates. As such the managerialist approach looks inward at the chosen practices of the organization and only considers how the society and environment impact the organization, rather than how the organization impacts society and the environment.

Arguably, the fourth stage ecosystem approach is not new to IC research and has its theoretical foundations in the work of Ahmed Bounfour. According to Chatzkel (2004, p. 339), it is Bonfour who in the late 1990s identified the transaction perspective as “the dominant perspective of capitalism” with efficiency being “the main driver for appraising individual and corporate actions”. In contrast, Bonfour argued that we need to provide a community perspective beyond organizational boundaries (see also, Gowthorpe, 2009).SS

p.33

How the fourth stage develops will be interesting because researchers are already using it to inspire their research and publish articles using the ecosystem approach. For example, Dameri and Ricciardi (2015) use the approach to study “Smart city intellectual capital”. Similarly, Secundo et al. (2016) use the IC fourth stage approach in developing an integrated IC framework for managing universities. Their article blends the IC fourth stage with a collective intelligence approach towards understanding how universities can achieve their third mission, which represents how universities “have moved from focusing exclusively on their traditional twin missions of teaching and research, towards a more active role for economic and cultural growth” (p. 298). Thus, fourth stage research is looking beyond the organization as to how IC benefits the wider ecosystem of society and the environment.

Is critical IC research running out of steam?

To conclude this chapter, it is worth reflecting on whether IC research is running out of steam. The evidence from a critical perspective is that IC research is healthy and making continuous insights into its use as a different way of looking at organizations and society beyond financial value (wealth) creation. The fourth stage, with its roots in critical social and environmental accounting, is the next, and potentially promising, area of critical IC research.

Additionally, there is a continuing discourse questioning the managerial approach to IC in an attempt to distance IC from a narrow to a broader focus. For example, Dumay (2016) has all but declared the death of IC reporting, which was at the heart of early academic and practitioner attempts to make IC relevant to organizations and their stakeholders, that is, aimed at shareholders and potential investors. However, the mantra that IC and intangibles are most important from an investor perspective lives on in continuing attempts to develop first and second stage research and practice agendas based on reporting (IIRC, 2013; Lev and Gu, 2016), showing how many researchers continue to be concerned with wealth creation, and not value creation (Dumay, 2016).

From an IC perspective, there is a potential resurgence in IC reporting because of the inclusion of IC, along with social and human capital, as part of the six capitals framework in the integrated reporting (<IR>) guidelines (IIRC, 2013). However, the <IR> guidelines have been suffering the same problem as IC in that there is a lower than expected take-up of <IR> than its supporters would like (Dumay, 2016), which has prompted a preliminary review of <IR> to understand the quality of <IR> adoption to date by examining issues such as interpreting the framework, costs, benefits, enablers and barriers to adoption, and the effectiveness of existing guidance and other tools.7 Such a review may be helpful in further advancing how IC is integrated into corporate business models, and there is a role for critical IC researchers to play in developing inputs into the <IR> debate.

However, there is also a role for critical IC researchers to play in moving beyond the wealth creation myth because once again, another framework has emerged advocating how accounting is broken and offering a new way forward. The latest intangibles and thus IC reporting proposal comes from the US, where Lev and Gu (2016) propose a new report called the Strategic Resources & Consequences Report based on the resource-based theory of the firm. The report looks strikingly similar to IC reports and includes both numeric and narrative information (Mouritsen et al., 2001a). However, the report is specifically targeted at investors and managers, and Lev and Gu (2016), rather than including social and environmental concerns, are somewhat dismissive of these essential elements of fourth stage IC. For example, Lev and Gu (2016, pp. 1722–1723) outline “Even major environmental disasters, like the Exxon Valdez spill (March 1989), were, in retrospect, just a hiccup in the relentless growth path of the company”. Unfortunately, there is a continuing discourse that considers intangibles as solely relevant for wealth creation and not for the benefit of society and the environment, or more disturbingly, despite society and the environment. Thus, there is a need for critical IC researchers to investigate the claims made by Lev and Gu (2016), and even take a stand against such biased rhetoric that puts profits before people.

p.34

While the above presents evidence that critical IC research is not running out of steam, the evidence also helps build an argument that IC research is becoming too narrow and disjointed. Notably, the Lev and Gu (2016) book is squarely targeted at a North American audience and this highlights the narrowness of research and thinking about intangible assets from an accounting perspective. However, from a European perspective, Cuozzo et al.’s (2017) recent review of IC disclosure studies reveals that the majority of IC disclosure research does not include the US, and the journals publishing IC disclosure studies are exclusively European journals.

IC research is also disjointed, because the term IC has different meanings in different contexts, especially in the US, where it is more synonymous with intellectual property (structural capital), rather than the combination of human, structural, and relational capital (Cuozzo et al., 2017). Eccles and Krzus (2010, p. 84) note “intangible assets generally has no accepted meaning and is used interchangeably with the terms intellectual assets, IC, and intangibles. We will treat them as one, using the term intangible assets for the sake of simplicity”. This quote reinforces that IC is ambiguous in different contexts.

As Cuozzo et al. (2017) outline, the term intangible assets is more common than IC in business parlance, while a narrow group of academics appear to be stuck on the term intellectual capital. The path forward for critical IC researchers is one that not only questions IC but also questions its foundations. Critical IC researchers need to recognize that IC means something different in different social, economic, and political contexts and there is a need to reflect on what and where we are researching. Doing so will help recharge the energy in the critical IC research agenda.

Fifth stage IC research: research without boundaries?

IC research is now almost 30 years old. However, it needs constant recharging if it is to remain relevant. In particular, by sticking to the narrow term intellectual capital based on a European conceptualization of IC, it will no doubt produce narrow research constrained to a narrow audience (Cuozzo et al., 2017). As outlined above, the research most people reading this book will be familiar with refers to IC as human, structural, and relational capital. Unfortunately, while the definition helps to categorize IC and help people understand what IC is, it also constrains our thinking. A good example is the concept of value creation, which traditionally is based on a shareholder or customer (utility) perspective (Bourguignon, 2005). As exemplified in fourth stage IC research, the value concept is extended to include social and environmental value (see, Dumay, 2016, pp. 169–171). However, extending IC to include two additional values also constrains thinking. In the fifth stage of IC research, IC researchers need to remove these boundaries, and the question they ask needs changing from ‘what is IC worth to investors, customers, society and the environment?’ to ‘is managing IC a worthwhile endeavour?’ Asking the latter question removes the boundaries from IC research to include all manner of worth and recognizes that IC is a substantial part of what impacts everyone on a day-to-day basis.

One of the main challenges faced is that because of different views on IC value, different forms of IC value have different worths to different people and we, as IC researchers, have yet to reconcile this point (see, Boltanski and Thévenot, 2006). As identified earlier, the recent book by Lev and Gu (2016) clearly shows that worth to many people is primarily focused on building a strong capital market and that identifying the intangible assets that create value is the only shareholder interest. They base their argument on the belief that if managers disclose more information about the key intangibles that create economic value, a major driver of economic growth, benefits ‘trickle down’ to all of society (Lev and Gu, 2016). The argument is similar to the theory espoused by Aghion and Bolton (1997, p. 151) whereby “it is widely believed that the accumulation of wealth by the rich is good for the poor since some of the increased wealth of the rich trickles down to the poor”. However, many IC researchers do not believe in the trickle-down theory and cannot reconcile that wealth creation is a paramount worth, especially when it relegates some members of society to poverty, and places weath creation ahead of social and environmental concerns. But without creating economic value, society cannot function either. So where is the balance? Or is there a balance?

p.35

In part, the current critical perspective on IC research may be partly to blame because it critiques the current thinking and has not done enough to expand IC boundaries. For example, Dumay (2009a) critiques the ‘accountingization’ of IC, rather than looking at the benefits of the approach that might provide valuable insights into how IC can be better measured economically, which in turn can help create economic value. While the European concept of IC research does not substantially focus on economic value, it appears that in North America they have taken the opposite approach and this helps explain why US researchers concentrate on investigating the accounting term intangible assets rather than IC (Eccles and Krzus, 2010, p. 84). In a society where wealth creation is considered paramount, this approach is consistent with the concept of worth.

Our observation is that these terms are generally used synonymously, yet the term intangible assets is much broader than those assets that create economic value and includes everything that is not tangible that is put to use to create value. However, we must also not forget that all forms of value creation always rely on tangible assets. For example, one of the key strengths of the <IR> approach is including financial, physical, and natural capital into its value creation model (IIRC, 2013), something that many IC researchers are only just coming to internalize. Therefore, it is time to take the boundaries off IC research and work towards reconciling the worth of IC to different people in different contexts and respecting that there will always be differences and that one view should not always prevail.

Notes

1 Chairman quits amid Skandia probe. The Evening Standard, 1 December 2003, p. 32.

2 Court sentences Skandia ex-CEO to jail for fraud. The Wall Street Journal Asia, 26 May 2006, p. 6.

3 As at 18 December 2016, the article had received 190 citations according to Google Scholar https://scholar.google.com.au/citations?user=zKFxle4AAAAJ&hl=en.

4 As at 26 December 2016, the article had 226 Google Scholar citations, see https://scholar.google.com.au/citations?view_op=view_citation&hl=en&user=zKFxle4AAAAJ&citation_for_view=zKFxle4AAAAJ:MXK_kJrjxJIC.

5 See www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/authors/literati/citations/awards.htm?id=2015, accessed 26 December 2016. The selection process made by Emerald Journal’s editorial experts is based initially on the citations being given to papers published in a previous year (in this case 2012). However, the judging panel also takes into account the content of the papers themselves in terms of novelty, inter-disciplinary interest, and relevancy in today’s world. While high academic and research standards are a prerequisite, these selections are ultimately peer-reviewed, but they are also a reflection of the high quality of work published in 2012.

p.36

6 Dumay, J. and Garanina, T. (2013), “Intellectual capital research: A critical examination of the third stage”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14 No. 1, pp. 10–25 is also a 2016 winner of a prestigious Emerald Citations of Excellence Award. See www.emeraldgrouppublishing.com/authors/literati/citations/awards.htm?id=2016, accessed 27 December 2016.

7 See www.linkedin.com/groups/7019864/7019864-6217239579909455876, accessed 28 December 2016.

References

Abeysekera, I. (2006), “The project of intellectual capital disclosure: Researching the research”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 61–77.

Aghion, P. and Bolton, P. (1997), “A theory of trickle-down growth and development”, The Review of Economic Studies, Vol. 64, No. 2, pp. 151–172.

Alvesson, M. and Deetz, S. (2000), Doing Critical Management Research, Sage, London.

Andriessen, D. (2004), “IC valuation and measurement: Classifying the state of the art”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 230–242.

Andriessen, D. (2006), “On the metaphorical nature of intellectual capital: A textual analysis”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 93–110.

April, K. A., Bosma, P. and Deglon, D. A. (2003), “IC measurement and reporting: Establishing a practice in SA mining”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 165–180.

Bakhru, A. (2004), “Managerial knowledge to organisational capability: New e-commerce businesses”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 326–336.

Barney, J. B. (1991), “Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage”, Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 99–120.

Boltanski, L. and Thévenot, L. (2006), On Justification: Economies of Worth, Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Bontis, N. (2003), “Intellectual capital disclosures in Canadian corporations”, Journal of Human Resource Costing and Accounting, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 9–20.

Bourguignon, A. (2005), “Management accounting and value creation: The profit and loss of reification”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 353–389.

Brennan, N. (2001), “Reporting intellectual capital in annual reports: Evidence from Ireland”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 423–436.

Caddy, I. (2000), “Intellectual capital: Recognizing both assets and liabilities”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 129–146.

Chaharbaghi, K. and Cripps, S. (2006), “Intellectual capital: Direction, not blind faith”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 29–42.

Chatzkel, J. (2004), “Moving through the crossroads”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 337–339.

Chiucchi, M. S. (2013), “Intellectual capital accounting in action: Enhancing learning through interventionist research”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 48–68.

Collier, P. M. (2001), “Valuing intellectual capacity in the police”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 437–455.

Cuozzo, B., Dumay, J., Palmaccio, M. and Lombardi, R. (2017), “Intellectual capital disclosure: A structured literature review”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 2–8.

Dameri, R. P. and Ricciardi, F. (2015), “Smart city intellectual capital:An emerging view of territorial systems innovation management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 860–887.

Demartini, P. and Paoloni, P. (2013), “Implementing an intellectual capital framework in practice”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 69–83.

Dierickx, I. and Cool, K. (1989), “Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage”, Management Science, Vol. 35, No. 12, pp. 1504–1511.

Dumay, J. (2008a), “Intellectual capital in action: Australian Studies”, University of Sydney, Sydney.

Dumay, J. (2008b), “Narrative disclosure of intellectual capital: A structurational analysis”, Management Research News, Vol. 31, No. 7, pp. 518–537.

Dumay, J. (2009a), “Intellectual capital measurement: A critical approach”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 190–210.

p.37

Dumay, J. (2009b), “Reflective discourse about intellectual capital: Research and practice”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 489–503.

Dumay, J. (2010), “A critical reflective discourse of an interventionist research project”, Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 46–70.

Dumay, J. (2012), “Grand theories as barriers to using IC concepts”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 4–15.

Dumay, J. (2013), “The third stage of IC: Towards a new IC future and beyond”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 5–9.

Dumay, J. (2016), “A critical reflection on the future of intellectual capital: From reporting to disclosure”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 168–184.

Dumay, J. and Baard, V. (2017), “An introduction to interventionist research in accounting”, in Hoque, Z., Parker, L. D., Covaleski, M. and Haynes, K. (Eds), The Routledge Companion to Qualitative Accounting Research Methods, Routledge, Taylor and Francis, Oxfordshire, UK.

Dumay, J. and Garanina, T. (2013), “Intellectual capital research: A critical examination of the third stage”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 10–25.

Dumay, J. and Tull, J. (2007), “Intellectual capital disclosure and price sensitive Australian stock exchange announcements”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 236–255.

Eccles, R. and Krzus, M. (2010), One Report: Integrated Reporting for a Sustainable Strategy, Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Edvinsson, L. (2013), “IC 21: Reflections from 21 years of IC practice and theory”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 163–172.

Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M. S. (1997), Intellectual Capital: Realising Your Company’s True Value by Finding its Hidden Brainpower, Harper Business, New York.

Fincham, R., Mouritsen, J. and Roslender, R. (2005), “Special issue on intellectual capital: Call for papers”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 351–352.

Giuliani, M. (2013), “Not all sunshine and roses: Discovering intellectual liabilities ‘in action’”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 127–144.

Gowthorpe, C. (2009), “Wider still and wider? A critical discussion of intellectual capital recognition, measurement and control in a boundary theoretical context”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 20, No. 7, pp. 823–834.

Grasenick, K. and Low, J. (2004), “Shaken, not stirred: Defining and connecting indicators for the measurement and valuation of intangibles”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 268–281.

Gray, R. (2006), “Social, environmental and sustainability reporting and organisational value creation? Whose value? Whose creation?”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 793–819.

Guthrie, J. and Dumay, J. (2015), “New frontiers in the use of intellectual capital in the public sector”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 258–266.

Guthrie, J., Dumay, J., Ricceri, F., and Nielsen, C. (Eds), (2017), The Routledge Companion to Intellectual Capital, Routledge, London.

Guthrie, J., Petty, R. and Johanson, U. (2001), “Sunrise in the knowledge economy: Managing, measuring and reporting intellectual capital”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 365–384.

Guthrie, J., Petty, R. and Ricceri, F. (2006), “The voluntary reporting of intellectual capital: Comparing evidence from Hong Kong and Australia”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 254–271.

Guthrie, J., Petty, R., Yongvanich, K. and Ricceri, F. (2004), “Using content analysis as a research method to inquire into intellectual capital reporting”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 282–293.

Guthrie, J., Ricceri, F. and Dumay, J. (2012), “Reflections and projections: A decade of intellectual capital accounting research”, The British Accounting Review, Vol. 44 No. 2, pp. 68–92.

Henry, L. (2013), “Intellectual capital in a recession: Evidence from UK SMEs”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 84–101.

Holland, J. (2001), “Financial institutions, intangibles and corporate governance”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 497–529.

Iazzolino, G. and Laise, D. (2013), “Value Added Intellectual Coefficient (VAIC): A methodological and critical review”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 547–63.

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) (2013), The International <IR> Framework, International Integrated Reporting Council London.

p.38

Jönsson, S. and Lukka, K. (2007), “There and back again: Doing interventionist research in management accounting”, in Chapman, C. S., Hopwood, A. G. and Shields, M. S. (Eds), Handbook of Management Accounting Research, Elsevier, Oxford, pp. 373–397.

Jørgensen, K. M. (2006), “Conceptualising intellectual capital as language game and power”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 78–92.

Joshi, M., Cahill, D., Sidhu, J. and Kansal, M. (2013), “Intellectual capital and financial performance: An evaluation of the Australian financial sector”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 264–285.

Kerr, S. (1995), “On the folly of rewarding A, while hoping for B”, Academy of Management Executive, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 7–14.

Latour, B. (1986), “The powers of association”, in Law, J. (Ed), Power, Action and Belief: A New Sociology of Knowledge?, Routledge & Kegan Paul, London, pp. 264–280.

Leitner, K.-H. and O’Donnell, D. (2007), “Conceptualizing IC management in R&D organizations: Future scenarios from the complexity theory perspective”, in Chaminade, C. and Catasús, B. (Eds), Intellectual Capital Revisited –Paradoxes in the Knowledge Organization, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham, UK & Northampton MA, USA, pp. 80–101.

Lev, B. and Gu, F. (2016), The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors and Managers, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Marr, B. and Chatzkel, J. (2004), “Intellectual capital at the crossroads: Managing, measuring, and reporting of IC”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 224–229.

Marr, B., Schiuma, G. and Neely, A. (2004), “The dynamics of value creation: Mapping your intellectual performance drivers”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 312–325.

Mårtensson, M. (2009), “Recounting counting and accounting: From political arithmetic to measuring intangibles and back”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 20, No. 7, pp. 835–846.

McPhail, K. (2009), “Where is the ethical knowledge in the knowledge economy? Power and potential in the emergence of ethical knowledge as a component of intellectual capital”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 20, No. 7, pp. 804–22.

Meritum Project (2002), Guidelines for Managing and Reporting on Intangibles (Intellectual Capital Report), European Commission, Madrid.

Mouritsen, J. (2004), “Measuring and intervening: How do we theorise intellectual capital management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 257–267.

Mouritsen, J. (2006), “Problematising intellectual capital research: Ostensive versus performative IC”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 820–841.

Mouritsen, J. and Roslender, R. (2009), “Critical intellectual capital”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 20, No. 7, pp. 801–803.

Mouritsen, J., Larsen, H. T. and Bukh, P. N. (2001a), “Intellectual capital and the ‘capable firm’: Narrating, visualising and numbering for managing knowledge”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 26, No. 7, pp. 735–762.

Mouritsen, J., Larsen, H. T. and Bukh, P. N. (2001b), “Valuing the future: Intellectual capital supplements at Skandia”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 399–422.

Nielsen, C. and Madsen, M. T. (2009), “Discourses of transparency in the intellectual capital reporting debate: Moving from generic reporting models to management defined information”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 20, No. 7, pp. 847–854.

O’Donnell, D. (2004), “Theory and method on intellectual capital creation: Addressing communicative action through relative methodics”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 294–311.

O’Donnell, D., Henriksen, L. B. and Voelpel, S. C. (2006a), “Guest editorial: Becoming critical on intellectual capital”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 5–11.

O’Donnell, D., Tracey, M., Henriksen, L. B., Bontis, N., Cleary, P., Kennedy, T. and O’Regan, P. (2006b), “On the ‘essential condition’ of intellectual capital: Labour!”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 111–128.

Oliver, G. R. (2013), “A micro intellectual capital knowledge flow model: A critical account of IC inside the classroom”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 145–162.

Ordóñez de Pablos, P. (2003), “Intellectual capital reporting in Spain: A comparative view”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 61–81.

Petty, R. and Guthrie, J. (2000), “Intellectual capital literature review: Measurement, reporting and management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 155–176.

p.39

Pike, S. and Roos, G. (2004), “Mathematics and modern business management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 243–256.

Pike, S., Boldt-Christmas, L. and Roos, G. (2006), “Intellectual capital: Origin and evolution”, International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 233–248.

Roos, J., Roos, G., Dragonetti, N. C. and Edvinsson, L. (1997), Intellectual Capital: Navigating in the New Business Landscape, Macmillan, Basingstoke, UK.

Roslender, R. and Fincham, R. (2001), “Thinking critically about intellectual capital accounting”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 383–399.

Roslender, R. and Stevenson, J. (2009), “Accounting for people: A real step forward or more a case of wishing and hoping?”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 20, No. 7, pp. 855–869.

Secundo, G., Dumay, J., Schiuma, G. and Passiante, G. (2016), “Managing intellectual capital through a collective intelligence approach: An integrated framework for universities”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 298–319.

Serenko, A. and Bontis, N. (2013), “Investigating the current state and impact of the intellectual capital academic discipline”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, pp. 476–500.

Skandia (1994), Visualising Intellectual Capital at Skandia: Supplement to Skandia’s 1994 Annual Report, Skandia Insurance Company Ltd, Stockholm.

Skandia (1995), Intellectual Capital: Value-Creating Processes: Supplement to Skandia’s 1995 Annual Report, Skandia Insurance Company Ltd, Stockholm.

Skandia (1996), Power of Innovation: Intellectual Capital Supplement to Skandia’s 1996 Interim Report, Skandia Insurance Company Ltd, Stockholm.

Skandia (1998), Human Capital in Transformation: Intellectual Capital Prototype Report, Skandia 1998, Skandia Insurance Company Ltd, Stockholm.

Snowden, D. J. and Boone, M. E. (2007), “A leader’s framework for decision making”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 85, No. 11, pp. 68–76.

Spender, J. C. (2006), “Method, philosophy and empirics in KM and IC”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 12–28.

Stewart, T. A. (1991), “Brainpower”, Fortune, Vol. 123, No. 11, pp. 44–50.

Stewart, T. A. (1997), Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organisations, Doubleday-Currency, London.

Stewart, T. A. and Losee, S. (1994), “Your company’s most valuable asset: Intellectual capital”, Fortune, Vol. 130, No. 7, pp. 68–73.

Stolowy, H. and Jeny-Cazavan, A. (2001), “International accounting disharmony: The case of intangibles”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 477–497.

Sveiby, K. E. (2007), “Methods for measuring intangible assets”, available at: www.sveiby.com/portals/0/articles/IntangibleMethods.htm (accessed 15 May 2007).

Sveiby, K. E. (2010), “Methods for measuring intangible assets”, available at: www.sveiby.com/portals/0/articles/IntangibleMethods.htm (accessed 22 August 2010).

Unerman, J., Guthrie, J. and Striukova, L. (2007), UK Reporting of Intellectual Capital, ICAEW, University of London.

Van der Meer-Kooistra, J. and Zijlstra, S. M. (2001), “Reporting on intellectual capital”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 456–476.

Voepel, S., Leibold, M., Eckhoff, R. and Davenport, T. (2006), “The tyranny of the Balanced Scorecard in the innovation economy”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 43–60.

Wasiluk, K. L. (2013), “Beyond eco-efficiency: Understanding CS through the IC practice lens”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 102–126.

Yu, A. and Humphreys, P. (2013), “From measuring to learning? Probing the evolutionary path of IC research and practice”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 26–47.