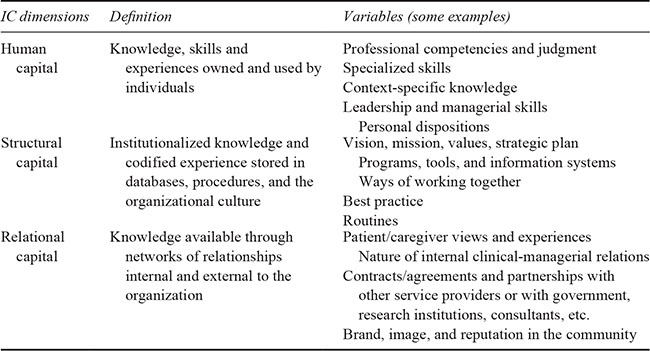

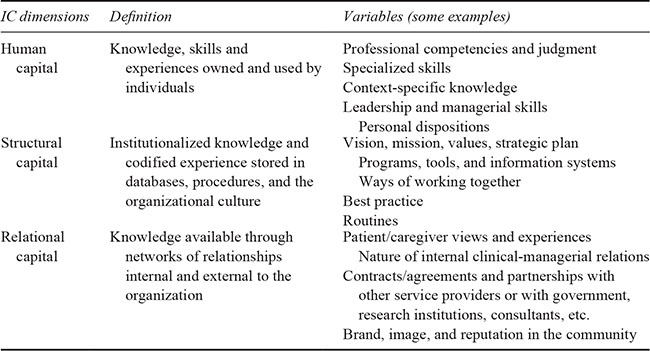

Table 7.1 IC in the healthcare organizations (Source: Evans et al., 2015, p. 4)

p.99

INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL IN THE CONTEXT OF HEALTHCARE ORGANIZATIONS

Emidia Vagnoni

Introduction

Healthcare organizations differ from other organizations because of their fundamental mission to guarantee health protection to citizens, and therefore their management process is driven by different criteria. Mark (2006, p. 851) argues:

[t]he scope of healthcare provision ranges from traditional healers in the developing world to medical consultants practising in the most sophisticated western hospitals. What they have in common is participation in an activity that requires trust between the parties concerned, to deliver a change in the patients’ well-being.

Historically, healthcare organizations have been shaped by the way in which healthcare has been provided (Porter, 2003), For example, the purpose of hospitals has changed over time from quarantine to clinical intervention. However, the approach to provision of healthcare is dependent on the country context (Mark, 2006, p. 852). During the late 1980s and early 1990s, many Western countries changed the relationship between state provision and the private sector (Hood, 1991), consistent with the philosophy of new public management (Ferlie, 1999; Barzelay, 2002). These reforms were aimed at increasing efficiency and introducing managed care and managed competition criteria (Toth, 2010). They were frequently implemented in a range of country contexts with a ‘one size fits all’ approach. The reforms introduced the new role of clinical director and new accounting technologies, both to measure results and monitor the healthcare organizations’ ability to challenge efficiency objectives (Llewellyn, 2001). Sheaff et al. (2003) highlights that measurement focuses only on what goes in and what comes out without looking at the process inside.

Health services’ delivery is the result of a complex process; a number of knowledge exchanges occurs among the actors of the process, and many individuals participate in sharing values, routines, protocols, and so on. The accounting literature has often depicted healthcare organizations from a financial perspective, highlighting the role of accounting technologies for management control. As both the healthcare organization as a whole and its sub-units have been examined (Vagnoni and Oppi, 2015), clinical directors have been assessed on their ability to contain costs, and financial issues have sometimes become the main drivers of healthcare organizations’ strategic management. However, many countries have recognized that the future of universal healthcare systems depends on the ability to respond to changing needs appropriately and in a way that is supported by the public. The ability of the healthcare organization to cope with innovation, knowledge management, and communication is crucial in a rapidly changing environment (Coulter and Jenkinson, 2005). Thus, intellectual capital (IC) is a comprehensive framework for valuing the particular characteristics of the healthcare environment. Specific to healthcare organizations is that the value creation process depends on a combination of both tangible and intangible assets, with the latter playing a dominant role. This means that managing IC helps the organization to create value and be responsive to health needs.

p.100

While there are many studies that examine IC and management, in terms of healthcare organizations IC is still a ‘black box’. Costs and financial results are identified, but how IC interacts to share knowledge and create innovation and value, is not known or monitored. Despite efforts to mobilize knowledge and innovation to legitimize healthcare organizations’ strategic role in society, the accounting literature has devoted surprisingly limited attention to these IC dimensions. This chapter aims to fill this gap.

The healthcare organization context

Both the managerial and medical literatures have pointed out the complexity of healthcare organizations (e.g. Mintzberg, 1983; Perrow, 1986; Institute of Medicine, 2001). Healthcare organizations are required to combine a wide range of production factors to deliver health services differentiated according to individual health needs. Furthermore, healthcare organizations’ outcomes are the result of a continuous innovation process. The specific focus of an innovation (a new drug, computer system, clinical intervention, professional role, and so on) cannot be isolated from its social, technical, and spatial contexts and, therefore, innovations often involve highly organized and systematically regulated changes in the structure and delivery of services (May, 2013).

Plsek (2003) highlighted some ‘properties’ relevant to understanding the drivers of innovation in complex systems: interaction among agents; rules and mental models; structures, processes, and patterns; and constant adaptation. Furthermore, Plsek and Wilson (2001) emphasized the role of knowledge, capabilities, and skills to manage effectively healthcare organizations. They argued those:

[w]ho seek to change an organization should harness the natural creativity and organizing ability of its staff and stakeholders through such principles as generative relationships, minimum specification, the positive use of attractors for change, and a constructive approach to variation in areas of practice where there is only moderate certainty and agreement (p. 746).

University hospitals play a key role in the health systems since they are affected by the logics of both healthcare and innovation (Miller and French, 2016). The university hospital model refers to an integrated organization in which academic, clinical, and research functions are performed. The activity of university hospitals involves patient care, teaching, and educational programmes for students, and research directed to the development of new diagnostic or therapeutic techniques. Therefore, the mission of university hospitals is the provision of a high-quality care, especially in the treatment of rare diseases and complex patients, the production of specialized services, the use of advanced technology, and conducting scientific research. University hospitals are focused on innovation, redesigning and improving models of care to respond to changing demand and integrating clinical activity with research and education. They include new skills developed through research into patient care, while students are taught how to practise.

p.101

While it is recognized in the literature that the university hospitals play a key role in the health care system (French and Miller, 2012) in terms of innovation and knowledge creation, their level of efficiency has been questioned (Lehrer and Burgess, 1995; Grosskopf et al., 2004), with Huttin and De Pouvourville (2001) finding that they are more costly than their non-teaching counterparts.

However, beyond efficiency and cost, there are important elements in university hospitals that relate to their IC resources. One of these is experience, described by Lerro and Schiuma (2013) as one of the critical success factors of the organization, as it is the ability to act promptly and safely in a specific field (Joe et al., 2013). Experience incorporates aspects of education, training, or competences and refers to the sphere of human capital, that is, those skills internal to the workforce and not obtainable from outside.

Another element, an important driver of competitive advantage, is the dissemination and sharing of knowledge within the organization, through the codification of skills and information, and their transmission to others in the form of explicit knowledge. This kind of knowledge is strongly linked to structural capital, as it allows the organization to enjoy internal capabilities that are shared and disseminated among professionals.

Finally, another element is the diffusion of knowledge within the organization both through networking among colleagues and with external professionals, which promotes what Gabbay and Le May (2004) defined as “mindlines”. Mindlines is part of relational capital in which professionals tend to avoid formal sources of knowledge but seek out tacit knowledge created by interactions with colleagues.

Although university hospitals may be considered a privileged setting in which to investigate IC, all healthcare organizations rely on knowledge to create value. Thus, knowledge, skills, and abilities are the drivers of innovation, and the main IC resources used by healthcare organization to create value.

The role of knowledge

In service organizations, knowledge is considered one of the most important IC resources and the management of knowledge aims at maximizing the organization’s knowledge-related effectiveness (Zhou and Fink, 2003). Successful management can give rise to a better allocation of work and activities, to more innovation, and to an environment that is receptive to change, particularly in competitive markets (Bishop et al., 2008). Health organizations can particularly benefit from knowledge management in terms of cost reduction, job flexibility, and reaction to patients’ needs, which can lead to better patient care (Zigan et al., 2010).

According to Brailer (1999, p. 6), the management of knowledge-related elements in health services is linked to “any systematic process designed to acquire, conserve, organize, retrieve, display and distribute what is known”. Reasons to deploy knowledge management in hospitals are the competitive differentiation with other organizations and the opportunity to improve quality of care, critical paths of care, collaborative care plans, evidence-based practice, and intra-organizational networks (Zigan et al., 2010).

p.102

According to Magnier-Watanabe and Senoo (2008), the acquisition of knowledge involves all processes that support gaining new knowledge from either inside or outside the organization: in university hospitals, new knowledge may come from colleagues through informal and personal contacts, from books, journals, conferences, or from investment in training programmes. University hospitals are characterized by the constant generation of new knowledge through research activities and through the frequent rotation of medical staff in training.

Furthermore, as argued by Zigan et al. (2010), the codification of knowledge is relevant because it concerns identifying, capturing, indexing, and making explicit knowledge that is ready for use by professionals, and the distribution and the presentation of knowledge is important because it refers to the transfer and sharing of knowledge through formal and informal mechanisms, such as meetings, relationships, or dialogue between organizational members. Hospitals can share knowledge through formal educational programmes, such as seminars, or they can transfer knowledge through the development of good working relationships among staff. Sharing knowledge reduces training costs and builds better working relationships.

Knowledge is an organizational asset that is important to share. Typical features of knowledge contribute to influence its relocation (Joe et al., 2013). In university hospitals, knowledge sharing behaviours are connected to the degree to which physicians share their knowledge and experience with others. Because their knowledge is indispensable to the care of patients in hospitals, physicians are considered a knowledge-intensive professional group. Sharing physicians’ knowledge within hospitals is critical in a competitive environment, and to increasing the quality and efficiency of care in health organizations (Ryu et al., 2003).

In research organizations such as university hospitals, knowledge can be categorized as implicit or explicit knowledge (Nonaka, 1994). Evidence-based healthcare imports explicit knowledge from research activities and incorporates it into practice, but it may underestimate the importance of implicit clinical knowledge. A study by Gabbay and Le May (2004) underlined the reluctance of physicians in the adoption of rigid formal sources of knowledge and their tendency to network with other professionals in order to develop “mindlines”.

In organizations, only a few individuals can be classified as experts, so the organization benefits from the diffusion of knowledge to other employees through sharing. Joe et al. (2013) define expertise as the capability to act with excellence in a specific subject, involving intellectual and cognitive efforts for a long period. Experts are therefore a potent source of value creation within organizations as they have a deep knowledge of a subject, a variety of experiences, and have been rigorously tested and trained over the course of a long career. An expert demonstrates high levels of efficiency, accuracy, and ability and holds subject specific knowledge on, for example, methods and procedures, including knowledge of how to deal with problems and new situations. Traits of knowledge contribute to transfer; for example, explicit knowledge is more easily transferred than tacit knowledge (Joe et al., 2013).

One of the main impacts from the departure of an expert may be the loss of credibility of the organization, as stakeholders may fear a reduction in the organization’s performance. Another impact is the inability to replace the professional, especially if highly specialized, with the consequent loss of customers or users (Joe et al., 2013).

Rondeau et al. (2009) investigated the negative effects of turnover among nursing staff. High turnover leads to higher workloads, negatively affects the morale of remaining staff, and reduces the productivity of those who have to train the new arrivals. Excessive turnover may also lead to workgroup conflict, decreased consensus and cohesion, and reduced job satisfaction due to changed communication patterns and social order. Turnover may lead to further turnover as otherwise satisfied employees consider leaving because of the increased stress of work, and excessive turnover may signal to remaining employees that there are better opportunities elsewhere. Kohn (2004) found that healthcare organizations need to enhance a good working atmosphere in order to attract excellent staff. They can achieve this, for example, by increasing autonomy and support staff and through investments in information and communication technology.

p.103

Although healthcare organizations can be considered late adopters of the knowledge management concept, some are starting to implement and evaluate knowledge management strategies (Kothari et al., 2011). Some management practices in healthcare focus on the use of information and communication technologies including electronic libraries, repositories containing research articles, and clinical or best practice guidelines to assist organizations in managing knowledge. However, this ICT-based evolution does not support knowledge development and sharing, and knowledge-based initiatives in healthcare organizations “tend to focus on one solution instead of a comprehensive strategy” (Kothari et al., 2011).

The clinical literature has shown the importance of knowledge, with studies discussing the relevance of capturing, sharing, and using knowledge within the daily work of health professionals (Chen, 2012; Lee et al., 2014). The health policy literature has also shown growing interest in knowledge management and knowledge mobilization in the health context, as argued by Ferlie et al. (2012). In their work, based on a literature review, the authors highlight the shift in terms of knowledge mobilization models. However, the public management and accounting literatures have not focused on healthcare organizations to date.

Why consider IC for managing healthcare organizations?

Nowadays organizations manage knowledge and IC because they acknowledge that value is added through the development of expertise, knowledge, and intangible assets (Lerro and Schiuma, 2013). The relevance of IC to creating value and enhancing performance, and its interaction with the accounting dimension of the organization, is highlighted by Guthrie and Petty (2000).

Mouritsen et al. (2001a) argue that IC focuses on organizing knowledge resources in order to make knowledge manageable; it is about actions and activities linked to knowledge, which are not easy to represent. According to this view, managing knowledge means being able to represent what is personal, questioning the idea of knowledge as an individual phenomenon. The established IC framework in which IC is categorized as human, structural, and relational, is supported by this view.

Human capital can be defined as the combination of individuals’ inherent qualities, education, experience, and attitudes (Hudson, 1993), and it includes knowledge, abilities, motivation, experience, and personal skills. Human capital is the principal source of innovation and strategic renewal (Bontis, 1998). In healthcare organizations, human capital refers to university education, training, professional experiences, but also to responsibility, to communicative abilities, to social competence, and ‘personal touch’ (Habersam and Piber, 2003).

Structural capital is defined as “the knowledge that stays within the firm at the end of the working day” (Meritum, 2002, p. 3). It is knowledge related to internal processes and structures, routines, procedures, systems, culture, technology, and databases.

Relational capital concerns all the resources external to the organization, such as consumers, users, research partners, funders, and other stakeholders. For an organization, it is “the value of its franchise, its ongoing relationships with the people or organizations to which it sells” (Stewart, 1997, p. 108).

p.104

Looking at these three dimensions separately does not provide a useful understanding of IC. It is important to note that IC does not consist of a stock of information, files, or paper, and it is not just what individuals know or how they work (Grantham et al., 1997). It is not even in the sum of these capitals: human, structural, and relational capital can be useful for organizations only if they are linked through ‘connectivity’. To this end, Habersam and Piber (2003) introduced connectivity as a fourth dimension of the IC framework, because it allows intensive-knowledge organizations, such as hospitals, to understand its IC as a whole, emphasizing the implications that the three dimensions have for each other. This is consistent with Bontis (1998), who considers IC as organizational learning flows, in which important knowledge cannot be transferred through education and training.

Guthrie et al. (2012) have underlined the importance of IC for management control and strategy areas. However, the focus on IC in regard to hospitals and healthcare organizations has been somewhat marginal, resulting in a lack of specific reporting models (Veltri et al., 2011). Within the public sector, hospitals differ because of their special characteristics, as outlined earlier. Creating knowledge is a key issue with regard to hospitals, and even more so for university hospitals (French and Miller, 2012). In that context, the process of value creation involves the use of technological, human, and organizational resources to create knowledge. Research organizations and university hospitals primarily invest in IC determinants, combining them to provide knowledge-based outputs, such as innovative services, consultancies, publications, or clinical pathways.

Nowadays, these organizations are challenging the managerial approach when thinking about effective and efficient allocation of resources, which are knowledge-based, particularly in light of growing competition for funds and with the implementation of new instruments for measuring and managing knowledge (Leitner and Warden, 2004). In addition to budget constraints and perceived inefficiency, the culture of university hospitals also makes a management-integrated system more challenging because of the isolation of decision making. Schwartz and Pogge (2000) point out that in order to survive, university hospitals have to be better integrated, giving up their autonomy and working more effectively. In particular, it is essential to expand cultural change to stakeholders, stimulating innovation, supporting the development of a learning organization, and involving physicians and professionals in a patient-centred system.

Through a strong integration policy and a focus on the management of IC, intensive-knowledge healthcare organizations, such as university hospitals, may be able to mobilize their unique assets to develop long-term advantage. Robinson (1998) highlighted three actions: first, attract and train a new generation of physician leaders who can reconcile the conflicting expectations of doctors, customers, regulators, partners, and other stakeholders; second, through aggregation of physicians, organizations can improve innovation and sharing of best clinical practice; three, sharing best practice supports and develops quality and efficiency.

Similar to for-profit and other public sector organizations, the value generated by healthcare providers cannot be fully expressed by traditional financial measures, but requires innovative measurement models able to present qualitative elements, including numbers, narratives, and visualizations. In hospitals, the IC reporting activity has to take into account their system of values and operating context, which requires a considerable effort by management (Habersam and Piber, 2003). As a knowledge-based organization, hospitals’ management can benefit from IC tools, which help to visualize the IC dimensions of the organizations. Any kind of measures and narratives related to IC determinants could be considered basic tools for depicting the IC of healthcare organizations.

p.105

Literature on IC in healthcare organizations

Habersam and Piber (2003) have pioneered the study of IC with regard to healthcare organizations, exploring the relevance and awareness of IC in the hospital setting through two qualitative case studies. While the IC accounting literature has mainly focused on for-profit organizations, discussing the contribution of IC to firms’ performance and developing models to visualize and report IC dimensions and variables, Habersam and Piber investigated the IC framework in public healthcare organizations. Analysing the characteristics and the practices of the two case studies against different cultural backgrounds – Italy and Austria – the authors complement the widespread taxonomy of IC consisting of human, structural, and relational capital by introducing connectivity capital as a linking device. Identifying the dynamic character of interactions between IC components, they proposed a new comprehensive and dynamic framework of IC. This takes into account that IC is characterized by process-driven collective and individual capabilities in interaction. As a consequence, Habersam and Piber argue for a co-existence of financial metrics and non-metric rationalities in order to achieve transparency of IC.

Peng et al. (2007) analysed how hospitals view the importance of IC and performance in the healthcare sector. Based on a pilot study, the authors identify the elements and relative importance of IC and performance measurement in Taiwanese hospitals. The IC framework was operationalized in 54 variables, 7 of which referred to human capital, 32 to organizational capital, and 15 to relational capital. The authors expect this study to be a starting point for exploring healthcare IC and performance, by identifying relevant variables and measures of IC.

The clinical literature has often focused knowledge and IC, mainly from the perspective of a single professional group. For example, Covell (2008) developed the middle-range theory of nursing IC, conceptualizing the level of nursing knowledge available within healthcare organizations. Covell’s work contributes to capturing the interrelationships between unit level variables within the work environment; nurses’ knowledge, skills, and experience; knowledge structures; and patient and organizational outcomes. The author emphasizes the role of structural, human, and relational capital within the work environment, through a focus on social capital (Cohen and Prusak 2001; Prusak, 2001), human capital investment, and human capital depletion (Bontis and Fitz-enz, 2002), which influence the development of human capital. The propositions of IC theory identify the factors within the work environment that influence the development of nursing stocks of knowledge, and the relationship of this knowledge to patient and organizational outcomes. Covell (2008) suggests a model that is based on both nursing staffing and employer support to nurses’ continuing professional development as the variables associated with nursing human capital; the latter affecting patients’ outcomes and organizational outcomes, while nursing structural capital affects only patients’ outcomes. The middle-range theory of nursing IC has strategic implications for healthcare organizations’ management: it can be useful to governments and professional organizations in policy development, and it can support administrators to determine the cost–benefit of allocated resources to continuous professional development of nurses. While the cost of professional development may be high, its influence on patient and organizational outcomes may contribute to cost savings and improved performance for the organization.

Evans et al. (2015) presented a review of the IC literature in healthcare published between 1990 and 2014, in which they identified the following key terms: intellectual capital/assets, knowledge capital/assets/resources, and intangible assets/resources. As a result of the analysis, an outline of IC in healthcare is presented (see Table 7.1). The authors conclude that the framework of IC offers a means by which to study value creation in healthcare organizations, to systematically manage these IC resources together, and to enhance mutually their interactions with performance.

p.106

Table 7.1 IC in the healthcare organizations (Source: Evans et al., 2015, p. 4)

Evans et al. (2015) focus on the use of IC for managerial purposes, recommending both scholars and practitioners break down what it means to “manage IC” (p. 12). They recognize the important role of managing and measuring IC both within and across healthcare organizations, as the organizations in this context face innovation to improve quality of care, cost containment, and integrated services. They call for more effective methods to enhance IC management.

IC accounting theory has challenged the ability of IC to improve the effectiveness of managerial processes, decision making, and strategic management. Based on an empirical study using an action research approach in a university hospital setting, Vagnoni and Oppi (2015) develop and apply an IC framework to enhance the visualization of strategic IC. Furthermore, the authors investigate the ability of IC to root changes in a real setting, both from an information system perspective and from a strategic management process. The paper strengthens the case for the use of an interventionist research approach that would give more insight into organizational practice, proving the ability of IC theory to contribute to hospital management. Finally, the authors provide guidelines for both academics and practitioners applying IC management to a hospital setting.

Pirozzi and Ferulano (2016) addressed the need to integrate healthcare organizations’ performance measurement systems with IC measures. Considering the gap between performance measurement approaches and the need to focus on both financial performance and clinical performance, the authors propose a model that provides a holistic representation of performance in healthcare organizations integrating different approaches stemming from intangible variables. Although the model could be used by administrators to manage and strategically control healthcare organizations more effectively, a discussion of the implications in practice is missing.

Most of the literature on IC in healthcare organizations aims at proposing new models, identifying IC variables, or proving the relevance of IC in the sector. Thus, authors have mainly analysed the literature to operationalize IC-related constructs or focused on case studies. Consequently, it can be argued that much of the literature related to IC in healthcare stems from the first and second stages of IC accounting studies (Guthrie et al., 2012). What is missing is studies from the third stage of IC, focusing on IC managerial implications (Dumay and Garanina, 2013).

p.107

Conclusion

Considering the characteristics of healthcare organizations and of health service delivery, IC resources are drivers of performance, yet in this context much strategic decision making and management is focused on financial dimensions. The need to contain health expenditures as defined means that IC measures that can determine the value of the health service – both from the patient experience and from a social perspective – are overlooked. The accounting literature has examined the importance of measuring, visualizing, and reporting IC to improve performance in both private and public sector organizations (Borins, 2001; Mouritsen et al., 2001b; Guthrie et al., 2012). As healthcare organizations are complex, IC has a particular role to play in strategic management. Identifying IC variables, their relationships, and how to mobilize them, has the potential to contribute to achieving financial goals as well as clinical outcomes, and staff administration. It is also this complexity that makes the study of healthcare organizations more challenging and may be one reason why there are a limited number of accounting studies of the role of IC in that context; medical journals have more widely studied the IC framework and its operationalization in different dimensions, as well as criticizing the lack of methods and approaches to effectively use IC for management and strategy. Clinicians have emphasized the role of knowledge and IC for healthcare management, while directors of healthcare organizations are under pressure in relation to budget constraints. In this context, IC accounting scholars can play a key role in bridging the gap and contributing to management and accounting practice change in the healthcare organizations. Thus, studies related to the use of IC frameworks for managerial purposes at all levels of the organization can contribute to changes in practice and to closing the gap between administrative and healthcare roles, creating greater trust among healthcare professionals in accounting technologies.

References

Barzelay, M. (2002), “Origins of the new public management: An international view from administration/political science”, in McLaughlin, K., Osborne, S. P. and Ferlie, E. (Eds), New Public Management: Current Trends and Future Prospects, Routledge, London, pp. 15–33.

Bishop, J., Boughlaghem, D., Glass, J., and Matsumoto, I. (2008), “Ensuring the effectiveness of a knowledge management initiative”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 16–29.

Bontis, N. (1998), “Intellectual capital: An exploratory study that develops measures and models”, Management Decision, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 63–76.

Bontis, N. and Fitz-enz, J. (2002), “Intellectual capital ROI: A causal map of human capital antecedents and consequents”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 223–247.

Borins, S. (2001), “Encouraging innovation in the public sector”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 310–319.

Brailer, D. (1999), “Management of knowledge in the modern health care delivery system”, Journal on Quality Improvement, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 6–19.

Chen, C. W. (2012), “Modelling and initiating knowledge management program using FQFD: A case study involving a healthcare institute”, Quality & Quantity, Vol. 46, No. 3, pp. 889–915.

Cohen, D. and Prusak, L. (2001), In Good Company: How Social Capital Makes Organizations Work, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Coulter, A. and Jenkinson, C. (2005), “European patients’ views on the responsiveness of health systems and healthcare providers”, The European Journal of Public Health, Vol. 15, No. 4, pp. 355–360.

Covell, C. L. (2008), “The middle-range theory of nursing intellectual capital”, Journal of Advanced Nursing, Vol. 63, No. 1, pp. 94–103.

Dumay, J. and Garanina, T. (2013), “Intellectual capital research: A critical examination of the third stage”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 10–25.

Evans, J. M., Brown, A., and Baker, G. R. (2015), “Intellectual capital in the healthcare sector: A systematic review and critique of the literature.” BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 556.

p.108

Ferlie, E. (1999), The Rise of the New Public Management: Inaugural Professorial Lecture Imperial College Management School, Imperial College, London.

Ferlie, E., Crilly, T., Jashapara, A., and Peckham, A. (2012), “Knowledge mobilisation in healthcare: A critical review of health sector and generic management literature”, Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 74, No. 8, pp. 1297–1304.

French, M. and Miller, F. A. (2012), “Leveraging the ‘living laboratory’: On the emergence of the entrepreneurial hospital”, Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 75, No. 4, pp. 717–724.

Gabbay, J. and Le May, A. (2004), “Evidence-based guidelines or collectively constructed mindlines? Ethnographic study of knowledge management in primary care”, British Medical Journal, Vol. 329, pp. 1013–1017.

Grantham, C. E., Nichols, L. D., and Schonberner, M. (1997), “A framework for the management of intellectual capital in the health care industry”, Journal of Health Care Finance, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 1–19.

Grosskopf, S., Margaritis, D., and Valdmanis, V. (2004), “Competitive effects on teaching hospitals”, European Journal of Operational Research, Vol. 154, No. 2, pp. 515–525.

Guthrie, J. and Petty, R. (2000), “Intellectual capital Australian annual reporting practices”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 241–251.

Guthrie, J., Ricceri, F., and Dumay, J. (2012), “Reflections and projections: A decade of intellectual capital accounting research”, British Accounting Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 68–92.

Habersam, M. and Piber, M. (2003), “Exploring intellectual capital in hospitals: Two qualitative case studies in Italy and Austria”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 753–779.

Hood, C. (1991), “A public management for all seasons”, Public Administration, Vol. 69, pp. 3–19.

Hudson, W. (1993), Intellectual Capital: How to Build it, Enhance it, Use it, John Wiley & Sons, New York.

Huttin, C. and de Pouvourville, G. (2001), “The impact of teaching and research on hospital costs”, The European Journal of Health, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 47–53.

Institute of Medicine (2001), Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health Care System for the 21st Century, National Academy Press, Washington, DC.

Joe, C., Yoong, P., and Patel, K. (2013), “Knowledge loss when older experts leave knowledge-intensive organisations”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 17, No. 6, pp. 913–927.

Kohn, L. T. (ed), (2004), The Academic Health Center as a Modeller: The Patient Care Role, The National Academies Press, Washington, DC.

Kothari, A., Hovanec, N., Hastie, R., and Sibbald, S. (2011), “Lessons from the business sector for successful knowledge management in health care: A systematic review”, BMC Health Services Research, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 173.

Lee, E. J., Kim, H. S., and Kim, H. Y. (2014), “Relationships between core factors of knowledge management in hospital nursing organisations and outcomes of nursing performance”, Journal of Clinical Nursing, Vol. 23, Nos 23–24, pp. 3513–3524.

Lehrer, L. A. and Burgess, J. F. (1995), “Teaching and hospital production: The use of regression estimates”, Health Economics, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 113–125.

Leitner, K. H. and Warden, C. (2004), “Managing and reporting knowledge-based resources and processes in research organisations: Specifics, lessons learned and perspectives”, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 33–51.

Lerro, A. and Schiuma, G. (2013), “Intellectual capital assessment practices: Overview and managerial implications”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 352–359.

Llewellyn, S. (2001), “Two-way windows’: Clinicians as medical managers”, Organization Studies, Vol. 22, No. 4, pp. 593–623.

Magnier-Watanabe, R. and Senoo, D. (2008), “Organizational characteristics as prescriptive factors of knowledge management initiatives”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 21–36.

Mark, A. L. (2006), “Notes from a small island: Researching organisational behaviour in healthcare from a UK perspective”, Journal of Organizational Behavior, Vol. 27, No. 7, pp. 851–867.

May, C. (2013), “Agency and implementation: Understanding the embedding of healthcare innovations in practice”, Social Science & Medicine, Vol. 78, pp. 26–33.

Meritum (2002), “Guidelines for managing and reporting on intangibles”, in Cañibano, L., Sánchez, P., Garcia-Ayuso, M., and Chaminade, C. (Eds), Meritum, Fundación Airtel Móvil, Madrid.

Miller, F. A. and French, M. (2016), “Organizing the entrepreneurial hospital: Hybridizing the logics of healthcare and innovation”, Research Policy, Vo. 45, No. 8, pp. 1534–1544.

Mintzberg, H. (1983), Power In and Around Organizations, Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ.

p.109

Mouritsen, J., Johansen, M. R., Larsen, H. T., and Bukh, P. N. (2001a), “Reading an intellectual capital statement: Describing and prescribing knowledge management strategies”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 2, No. 4, pp. 359–383.

Mouritsen, J., Larsen, H. T., and Bukh, P. N. (2001b), “Intellectual capital and the ‘capable firm’: Narrating, visualising and numbering for managing knowledge”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vo. 26, No. 7, pp. 735–762.

Nonaka, I. (1994), “A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation”, Organization Science, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 14–37.

Peng, T. J. A., Pike, S., and Roos, G. (2007), “Intellectual capital and performance indicators: Taiwanese healthcare sector”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 538–556.

Perrow, C. (1986), “Economic theories of organization”, Theory and Society, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 11–45.

Pirozzi, M. G. and Ferulano, G. P. (2016), “Intellectual capital and performance measurement in healthcare organizations: An integrated new model”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 320–350.

Plsek, P. E. (2003), “Complexity and the adoption of innovation in health care”, in Proceedings of Accelerating Quality Improvement in Health Care: Strategies to Speed the Diffusion of Evidence-Based Innovations, National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation, Washington, DC, 27–28 January 2003.

Plsek, P. E. and Wilson, T. (2001), “Complexity, leadership, and management in healthcare organisations”, British Medical Journal, Vol. 323, No. 7315, pp. 746–749.

Porter, R. (2003), Blood and Guts: A Short History of Medicine, Allen Lane, London

Prusak, L. (2001), “Where did knowledge management come from?”, IBM Systems Journal, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 1002–1007.

Robinson, J. C. (1998), “Financial capital and intellectual capital in physician practice management”, Health Affairs, Vol. 17, No. 4, pp. 53–74.

Rondeau, V., Jacqmin-Gadda, H., Commenges, D., Helmer, C., and Dartigues, J. F. (2009), “Aluminum and silica in drinking water and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease or cognitive decline: Findings from 15-year follow-up of the PAQUID cohort”, American Journal of Epidemiology, Vol. 169, No. 4, pp. 489–496.

Ryu, S., Ho, S.H., and Han, I. (2003), “Knowledge sharing behavior of physicians in hospitals. Expert systems with applications”, Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 113–122.

Schwartz, R.W. and Pogge, C. (2000), “Physician leadership is essential to the survival of teaching hospitals”, The American Journal of Surgery, Vol. 179, pp. 462–468.

Sheaff, R., Schofield, J., Mannion, R., Dowling, B., Marshall, M., and McNally, R. (2003), Organisational Factors and Performance: A Review of the Literature, NCCSDO, London.

Stewart, T. A. (1997), Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations, Nicholas Brealey Publishing, London.

Toth, F. (2010), “Healthcare policies over the last 20 years: Reforms and counter-reforms”, Health Policy, Vol. 95, No. 1, pp. 82–89.

Vagnoni, E. and Oppi, C. (2015), “Investigating factors of intellectual capital to enhance achievement of strategic goals in a university hospital setting”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 331–363.

Veltri, S., Bronzetti, G., and Sicoli, G. (2011), “Il Report del Capitale Intellettuale in Sanità: Specificità, Lezioni Apprese, Prospettive di Ricerca”, Mecosan, Vol. 20, No. 78, pp. 101–112.

Zhou, A. Z. and Fink, D. (2003), “The intellectual capital web: A systematic linking of intellectual capital and knowledge management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 4, No. 1, pp. 34–48.

Zigan, K., Macfarlane, F., and Desombre, T. (2010), “Knowledge management in secondary care: A case study”, Knowledge Process Management, Vol. 17, pp. 118–127.