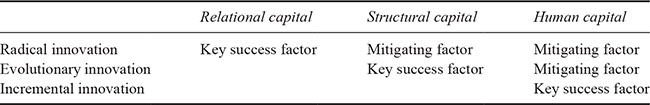

Table 12.1 Links between IC and innovation

Source: Adapted from Dumay et al., 2013, p. 626

p.185

INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL AND INNOVATION

Jim Rooney and John Dumay

Introduction

Innovation has been identified as “the principal determinant of competitiveness” (Petty and Guthrie, 2000, p. 157). However, research has also shown that it is multi-faceted and multi-dimensional (Tidd, 2001, p. 169). In particular, the innovation process is “power and value-laden” (Dumay et al., 2013, p. 609) with outcomes that are difficult to predict (Tidd, 2001). Further, the literature on innovation in strategic practice identifies gaps between perceptions of innovation and awareness of the common characteristics of successful innovation (Cooper and Kleinschmidt, 1993, p. 74). Here, researchers find that the role of subjective judgment and its behavioural implications have strong links to innovation and its management (Bisbe and Otley, 2004; Chenhall and Moers, 2015).

According to the Oslo Manual issued by the OECD/Eurostat (2005, p. 46), “Innovation is the implementation of a new or significantly improved product (good or service), process, new marketing method or a new organisational method in business practices, workplace organisation or external relations”. Thus, innovation is a broad concept encompassing all levels of product, service, and process improvement from the smallest change to the most radical invention. Quite simply, innovation is doing something different today than you did yesterday (Smith et al., 2005).

Intellectual capital (IC), in its various guises (including processes and capabilities), has also been identified in the management literature as a source of innovation (for example, Benner and Tushman, 2003, p. 242). However, past interest has been on linking IC and innovation from an ostensive perspective (Mouritsen, 2006), along with continued efforts to justify these links empirically (Martín de Castro and López Sáez, 2008; Delgado-Verde et al., 2011).

It is worth noting that the tendency in such research has been to focus on the positive aspects of innovation (Dumay et al., 2013, p. 612). For example, in the economics literature, “innovation has been included in the capital accumulation concept” (Galindo and Mendez-Picazo, 2013, p. 502). Despite this research, the relationship between IC and innovation is considered, in many aspects, to be “unresolved” (Delgado-Verde et al., 2016, p. 35).

In this chapter, the focus is on research that explores the behavioural influences on innovation practice and their association with IC, especially through narratives, which are associated with communication of IC inside and outside organizations (Dumay, 2008; Dumay and Roslender, 2013). We examine performative interactions between IC and innovation practice, including how IC contributes towards innovation based on a continuum including radical, evolutionary, and incremental innovation. As identified by Dumay et al. (2013, p. 627), “different types of IC influence different forms of innovation”. Understanding the implications and influences of these types of IC has theoretical as well as practitioner benefits.

p.186

An overview of the link between IC and innovation

In the academic literature, the recursive contribution of innovation to business competitiveness has been widely investigated (Teece et al., 1997). Following Schumpeter, several authors have considered innovation as a critical source of competitive advantage in the context of an ever-evolving business and technological environment (Tushman and O’Reilly, 1996, p. 36; Christensen and Raynor, 1997, p. 31). Therefore, understanding how firms achieve and sustain competitive advantage in this environment is fundamental (Tsai and Yang, 2013). As Teece et al. (1997, p. 509) argue, this “is especially relevant in a Schumpeterian world of innovation-based competition”. Given the relationship between IC and value creation through innovation (Hermans and Kauranen, 2005, p. 183), this understanding is also an IC story.

Unfortunately, not all innovations are successful, with many failing to live up to the promised outcomes. Even firms acknowledged for past innovation (for example, Apple) have had their fair share of unsuccessful products, such as the Newton PDAs, PiPPiN game consoles, and Macintosh TVs (see Gardiner, 2008). Further, such companies can easily lose their way if they do not keep up with changes in their product markets. Witness the profit demise of Nokia, which until the introduction of the iPhone was the leading manufacturer of mobile phones at a considerable profit. However, Nokia’s profits soured, losing €487 million in the second quarter of 2011 as it felt the sting of competition from the iPhone and Android-based smartphones (Nokia Press Release, 2011–04–21).1 The rest is history, and now, Nokia is no more.

This mixed outcome highlights a problem in understanding the different factors that enable innovation due to the gap between managers’ perceptions of innovation and awareness of criteria for successful innovation (Cooper and Kleinschmidt, 1993, p. 74). Compounding this problem is the difficulty in establishing a relationship between measures of innovation and firm performance (Tidd, 2001, p. 169), a problem in common with management accounting research (Pitkanen and Lukka, 2011, p. 125). Similar to IC, making a link between innovation and a firm is difficult because the innovation process is unpredictable, making the measurement of its inputs and outputs challenging.

Some authors go as far as claiming that successful innovations are a result of luck (Barney, 1986). Borrowing from the resource-based-view of the firm, Dierickx and Cool (1989, p. 1508) take this one step further and outline the “jackpot” model of R&D in relation to radical innovation as “firms sink R&D flows in projects with highly uncertain outcomes, and only a few firms actually ‘hit the jackpot’ by bringing out highly successful products”. Therefore, the literature does not advocate one best way to strategize, manage, or measure innovation. Rather, the strategic approach to innovation is contingent on a range of factors such as the business environment, organizational performance, organizational structure, and the design and type of innovation (Tidd, 2001, pp. 173–4).

Early practitioner implementations of IC practice identified innovation as being central to justifying investment in measuring, managing, and reporting IC. For example, innovation capital is featured in the original Skandia Navigator and is defined as the “Renewal strength in a company, expressed as protected commercial rights, intellectual property, and other intangible assets and values” (Skandia, 1996, p. 22). The link between IC and innovation gained more prominence after Skandia entitled its subsequent report Power of Innovation and declared “Innovation is now understood as the driving force behind increases in wealth” (Skandia, 1996, p. 3).

p.187

At the turn of the millennium, the link between IC and innovation through practice was embraced by governments and policy-makers interested in promoting innovation within national economies as a source of growth and economic prosperity. As outlined in the Meritum Project (2002, p. 59):

[t]he disclosure of a greater amount of reliable information on the firm’s intangible investments may help overcome the problems currently affecting the validity of the results of innovation studies. For it will facilitate the design and implementation of public policies aimed at increasing economic growth and social welfare by promoting innovation.

Over time, policy-making progressed to lauding the power of IC to promote innovation through the refinement of internal company processes. The policy link is exemplified in the Danish IC guidelines, developed with the support of the Danish Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (Mouritsen et al., 2003, p. 11):

Processes relate to the knowledge content embedded in the company’s stable procedures and routines. These can be the company’s innovation processes and quality procedures, management and control processes and mechanisms for handling information.

There have been several other IC initiatives linking the development of IC to innovation. A prime example is the European Commission (EC) sponsored RICARDIS report, whereby the authors advocate that:

Intellectual Capital is a key element in an organization’s future earning potential. Theoretical and empirical studies show that it is the unique combination of the different elements of Intellectual Capital and tangible investments that determines an enterprise’s competitive advantage. R&D and innovation can be regarded as one element of Intellectual Capital. However, research intensive enterprises invest not only in R&D and innovation, but also in other forms of Intellectual Capital. Empirical studies provide evidence for the tight link and contingency between investments in R&D, Innovation, Human Resources and Relational Capital.

(European Commission, 2006, p. 10)

A more contemporary example can be found in another EC sponsored project, InCAS (Intellectual Capital Statement: Made in Europe). In line with the RICARDIS argument, the authors advocate the link between IC, innovation, and competitive advantage (Humphreys et al., 2010, p. 4):

As a result of constant changes caused by globalization, emerging technologies and shorter product life-cycles, knowledge and innovation have already become the main competitive advantages of many companies … Intellectual Capital (IC) forms the basis for high quality products and services as well as for organizational innovations. So far, conventional management instruments and balance sheets do not cover the systematic management of IC.

p.188

As can be seen in the evolution of these IC statement guidelines, policy-makers were seeking to convince themselves and others of the need to develop IC by promoting the ‘grand theory’ that IC is necessary for innovation (Llewellyn, 2003; Dumay, 2012). However, it seems that policy-makers have yet to achieve this end. Despite continuing exhortations for organizations to develop IC to promote innovation that will lead to competitive advantage and the arguments to disclose innovation in IC reports, it seems that the propensity of organizations to publish IC statements is at a low ebb, and has even been declared dead (Dumay, 2016). Thus, the public disclosure of innovation and IC is now lower than when the guidelines were developed. So how can organizations implement and control innovation through an IC lens?

Linking innovation and IC through narrative

Borrowing from the strong tradition of IC narratives (Dumay, 2008; Dumay and Roslender, 2013), we argue that to implement and control innovation through an IC lens innovation narratives can be used as a coordination device as “they have the power to explain innovation processes so that they are comprehensible and appear legitimate” (Bartel and Garud, 2009, p. 107). Innovation narratives act as a sense-making device designed to create a common understanding of what the organization is trying to achieve. They act to persuade people involved in innovative processes “to take cognizance of the . . . consequences of their decisions” (Llewellyn, 1999, p. 239). Thus, managers who can deploy innovation narratives effectively can potentially control the process of innovation.

Here the role of narrative in the process of controlling for innovation is also related to how innovation is measured because narratives are crucial in conveying the meaning of numbers (Dumay and Rooney, 2016). As Llewellyn (1999, p. 220) observes, “people reason, learn and persuade in two distinct modes – through stories (narration) and by numbers (calculation)” and “in everyday life narration is privileged over calculation”. Narrative predominates in sense-making because people have what is known as “narrative capacity and can judge probability and fidelity” of arguments made in a narrative (Weick and Browning, 1986, p. 249). The problem with relying solely on the calculation of numbers is that most people who participate in innovative processes are not accountants or ‘experts’ at measuring. As a result, Weick and Browning (1986, p. 249) contend:

In a rational paradigm that undergirds argumentation (calculations), only experts can debate experts, which means that non-experts are spectators. In the narrative paradigm, when the topic is nontechnical, experts are storytellers just like everyone else, which means that non-experts can be more active participants.

The participation of interested people who are not IC or measurement experts is essential to innovation processes because, as Bartel and Garud (2009, p. 107) espouse, “innovation requires the coordinated efforts of many actors to facilitate” generating ideas, solving problems, and linking past experiences to future ambitions. Similar findings emanate from later research on collaborative networks (Kolleck and Bormann, 2014) and knowledge sharing between professional communities (Kimble et al., 2010). In response, Bartel and Garud (2009, p. 108) identify two specific types of innovation narrative, provisional and structured. The narratives promote the coordinated action of actors during the innovation process, symbolize the boundaries of acceptable behaviour, are a mechanism for sharing information about past innovations, and inspire new ideas.

Provisional innovation narratives are used to enable real-time problem solving to help coordinate the efforts of different actors. These narratives are emergent in nature and unlike fully formed stories replete with a plot, protagonist, and outcomes. Provisional narratives are based on innovations in progress and are speculative about the outcome of the innovation at hand. These narratives help to coordinate the efforts of those involved in the innovation process by framing the problem definition to find solutions. Thus, unlike fully formed stories, they are fleeting, ever-evolving, and are more than likely to be communicated in the day-to-day conversation of the actors involved rather than being recorded. Being conversations, they can enrol the interest of listeners and alter their conception of how the innovation relates to the rest of the organization (Bartel and Garud, 2009, pp. 112–13). Related research on the use of ethnographic methodologies in studying innovation processes (Hoholm and Araujo, 2011, p. 938) posit that “This real-time tracking of processes enabled the systematic development of analytical frame-works and theorizing, taking controversy and uncertainty of how to relate the innovation to other networks and processes as a starting point”.

p.189

In contrast, structured innovation narratives coordinate the past, present, and future of innovation processes to allow the organization to learn from its experiences. These narratives preserve “actors and their activities, material artefacts and how they are transformed during the innovation process” (Bartel and Garud, 2009, p. 113). From an academic perspective these narratives are related to the case study papers found in academic journals that tell the story of how specific innovation challenges were tackled and overcome from a historical context (see Blundel, 2006). Structured narratives also help to highlight the complexity of innovation processes and capture the tensions between emerging ideas and current operations to highlight how innovative processes are non-linear and do not guarantee success (Bartel and Garud, 2009, pp. 113–14). Structured innovation narratives also provide a rich source of research data and have been used to build models of innovation in particular contexts (see Ellonen and Karhu, 2006). It is these structured innovation narratives that would be found in IC reports, especially the original reports developed by Skandia (1996). However, as discussed previously, these reports are no longer commonly found externally, so there also needs to be a further way of understanding how innovation works inside an organization from an IC perspective beyond the grand theory linking IC and innovation.

The differing roles of IC across the innovation continuum

Researchers continue to seek evidence to prove the grand theory linking IC to innovation. The problem with any grand theory is that it represents “meta-narratives formulated at a high level of generality and reflect[s] ideas that have been arrived at by thinking through the issues and relationships in an abstract way – rather than being derived from empirical research” (Llewellyn, 2003, p. 676).

In response, many studies attempt to demonstrate that developing IC and innovation is beneficial and this is almost never questioned (Sveiby et al., 2012). For example, Delgado-Verde et al. (2011, p. 5) claim that “Organizational knowledge assets are key organizational factors responsible for firm innovation, as well as effective management”. In their article, they declare “The main contribution of the empirical findings of this research is precisely providing evidence that supports that organizational [structural] capital is one of the main sources for firm innovation” Delgado-Verde et al. (2011, p. 14). Research, as exemplified by Delgado-Verde et al. (2011), is needed to develop more “differentiation theories” (Llewellyn, 2003, p. 672) of IC practice, whereby researchers establish the “meaning and significance” of innovation “through setting up contrasts and categories” to link specific IC elements to innovation.

An example of how specific IC categories link to innovation is provided by Dumay et al. (2013), who investigated impediments to innovation practice using an IC lens. In their research, Dumay et al. (2013) challenge the notion that all aspects of IC are equally important in developing innovation and that innovation is multi-faceted and not all innovations are successful. To conduct their research, Dumay et al. (2013) gathered structured innovation narratives in semi-structured interviews with 27 Australian executive managers. The interviews elicited structured innovation narratives about successful and unsuccessful innovations to identify both enablers and impediments to innovation.

p.190

One important aspect of the Dumay et al. (2013) research is that they place different types of innovation on a continuum, rather than just consider innovation to be radical or incremental. They explain the continuum as follows (Dumay et al., 2013, pp. 614–5).

• Radical innovation relates to the classical notion of Schumpeterian innovation (Schumpeter, 1934), in that managers recognize that what is developed represents a discontinuity/disruption of what was before (Dosi, 1982, p. 147). Radical innovation is associated with breakthrough ideas (Gundling, 2000; O’Connor and Rice, 2001) and with the development of new business or product lines based on new ideas or technologies or substantial cost reductions that transform the economics of a business (Leifer et al., 2000).

• Evolutionary innovation is typically an expansion of, or significant change to, current products and services, vertical integration, expansion of core competencies or exploring a significantly new market (see Pascale, 1984; Kay and Goldspink, 2013). In contrast to radical innovations, evolutionary innovation does not “re-write the rules of the competitive game, creating a new value proposition” and is more than “continuous movement in the cost/performance frontier” (Tidd et al., 2005).

• Incremental innovation represents an improvement to current business models not involving significant change. It often involves fixing problems with current operations rather than creating new operations. There is a high level of certainty about the internal and external business environments. Incremental innovation is a gradual change and improvement, and product and processes are modified starting from what there was before (McGuigan and Henderson, 2005, p. 199).

Overall, the findings of Dumay et al. (2013) are consistent with the grand theory linking IC to successful innovation because all forms of successful innovation require human, structural, and customer capital. However, if different IC elements are not recognized for what they contribute to specific innovation types, then this could lead to innovation failures. Thus, the Dumay et al. (2013) findings also contrast with the grand theory, by finding that a mix of IC components leads to a nuanced understanding of the IC-innovation relationship as shown in Table 12.1.

Based on the findings of Dumay et al. (2013), we briefly examine the categories of innovation highlighted earlier in this chapter and their links to IC as presented in Table 12.1.

p.191

Radical innovation

Although all three IC types are useful in encouraging radical innovation, relational capital appears to be the most significant regarding an effective relationship between IC and innovation practice. Here two factors emerge from the findings of Dumay et al. (2013). First, selection of the ‘right’ partner is perhaps the most important success factor in order to ensure cooperation and support for a common vision. Indeed this appears to be substantially more important than commonly discussed factors such as entrepreneur personality and organizational culture (Colombo et al., 2015). There are, however, differences between the related factors dependent on the life cycle stage of the individual firm (Ripolles and Blesa, 2016). Second, a focus on ‘unseen’ customer needs is critical to radical innovation. In the business literature, this factor has been identified as important for both start-up (Lumkin and Dess, 2001; Paradkar et al., 2015) and mature firms (Tripsas, 2008). The importance of this factor cannot be considered in isolation, as Dumay et al. (2013, p. 622) identify “the process of uncovering the unseen needs is developed as a portfolio of ideas with the help of partners who contribute capabilities, capacity or social capital, [and] uncertainty is gradually and systematically reduced over time”.

From a strucutural capital perspective, it is also a mitagating factor because developing rigid processes is not seen as a key success factor for developing successful innovations. In fact Dumay et al. (2013, p. 622) find that the need to balance rational considerations of likely success before committing to an individual innovation is detrimental to, rather than enabling of, innovation. Here, the innovation process followed is more akin to Dierickx and Cool’s (1989, p. 1508) ‘jackpot’ model of innovation, which advocates that “Firms sink R&D flows in projects with highly uncertain outcomes, and only few firms actually ‘hit the jackpot’ by bringing out highly successful products”. Therefore, while organizations are not entirely laissez faire about innovation, many successful innovations were not developed using overly rigid innovation processes, as bureaucracy could actually hamper rather than promote innovation.

Interestingly, human capital is identified as a mitigating factor for successful radical innovation rather than being critical to it. Dumay et al. (2013, p. 621) find that there is a relative absence of personality and organizational culture as factors in successful radical innovation, which is in contrast to the belief that human capital drives innovation. While it is true that some people can drive innovation at this level, for example Steve Jobs at Apple, human capital seems to play a secondary role to developing relationships with external actors who help to influence the success or failure of an innovation. Additionally, relying on just one or two people to drive innovation can have devastating results should that one person leave or run out of ideas. As Dumay et al. (2013, p. 621) conclude, what the “results highlight is that the role of individual personalities in radical innovation is more subtle than the leadership literature would suggest, but that does not mean it is unnecessary”.

Evolutionary innovation

Given a focus on ‘top-down impetus’ for evolutionary innovation (Dumay et al., 2013, p. 622), the exercise of internal power relationships becomes more critical to this category of innovation (for example, see Ratten, 2015, p. 318). However, in common with other IC/innovation relationships outlined earlier, the interaction is multi-level and contextual (for example, see Lees and Sexton, 2014). As highlighted by Dumay et al. (2013, p. 627), IC in the form of human capital is important in evolutionary innovation, particularly in the form of leadership “personality and internal communication within the innovating firm”. However, as with radical innovation, it can be a mitigating factor because unless the person driving the innovation can inspire the team to follow, then success is not guaranteed.

p.192

With evolutionary innovation, forms of structural capital, such as technology, provide essential support to existing human capital. Additionally, Dumay et al. (2013, p. 627) find that there needs to be an organizational environment for innovation that is not just cultural, but also requires clearly outlined organizational structures that include requisite management controls essential for enabling innovations to develop.

Incremental innovation

In relation to this final category of innovation, the focus is on product and process enhancement, which requires a greater need for “human capital in the form of organisational culture” (Dumay et al., 2013, p. 627). In incremental innovation, the problem and viable solution are already clearly identified and require human resources to implement the solution, as a manager from the Dumay et al. (2013, p. 627) study outlines:

So what we realized was for us to be good collectively, we had to change the individual view of success from a context of “me” to “we”. Once we did that and we created an understanding that it’s the bigger picture.

Unlike radical innovation, which does not occur in all organizations, incremental innovation is found in the day-to-day operations of organizations as they strive to improve processes. It is only through the constant interactions of employees and managers working on improving organizational processes and products that incremental innovations take place, and a strong organizational culture is needed to support such change.

Conclusions and implications for theory and practice

In this chapter, we have examined innovation practice and its association with IC, especially through narratives, rather than numbers. These associations were examined across a continuum including radical, evolutionary, and incremental innovation. Our exploration is based on the literature linking IC and innovation practice associated with the use or implementation of these concepts. In contrast to the prior literature, however, we have explored empirical findings beyond the grand theory linking IC and innovation. From the discussions in this chapter, we demonstrate and conclude that the relationships between IC and innovation are substantively more nuanced than the IC-innovation grand theory suggests. We conclude that different types of IC are more effective for different categories of innovation, and can also be mitigating factors in developing innovations, going some way to explaining the mixed empirical results of prior IC-innovation studies.

These findings have a number of implications for IC and innovation practice, research, and policy-making. First, for practitioners, there is an imperative to resist the temptation to apply quantitative frameworks based on grand IC theories without critical review of the nuanced relationship between IC type and innovation categories. Given that innovation is, to a considerable extent, driven by strategy, there is a need for clarity on the desired strategic outcomes. Second, for researchers there is a need to consider the influences on innovation failure as well as success. As for practitioners, this requires a more critical and nuanced understanding of the various relationships between IC type and the continuum of innovation categories not usually examined in grand theories of IC. Finally, for policy-makers, there is a need to critically analyse past preferences for ‘one size fits all’ innovation policies. All forms of innovation have a role in achieving national and global economic goals.

p.193

Note

1 Nokia Press Release (2011-04-21), http://press.nokia.com/2011/07/21/nokia-q2-2011-net-sales-eur-9-3-billion-non-ifrs-eps-eur-0-06-reported-eps-eur-0-10/. (accessed 27 December 2011).

References

Barney, J. B. (1986), “Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy”, Management Science, Vol. 32, No. 10, pp. 1231–1241.

Bartel, C. A. and Garud, R. (2009), “The role of narratives in sustaining organizational innovation”, Organization Science, Vol. 20, No. 1, pp. 107–117.

Benner, M. J. and Tushman, M. L. (2003), “Exploitation, exploration, and process management: The productivity dilemma revisited”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 28, No. 2, pp. 238–256.

Bisbe, J. and Otley, D. (2004), “The effects of the interactive use of management control systems on product innovation”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 29, pp. 709–737.

Blundel, R. (2006), “‘Little ships’: The co-evolution of technological capabilities and industrial dynamics in competing innovation networks”, Industry & Innovation, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 313–334.

Chenhall, R. H. and Moers, F. (2015), “The role of innovation in the evolution of management accounting and its integration into management control”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 47, pp. 1–13.

Christensen, C. and Raynor, M. (1997), The Innovator’s Solution. Creating and Sustaining Successful Growth, Harvard Business Review Press, Cambridge, MA.

Colombo, M. G., Franzoni, C., and Veugelers, R. (2015), “Going radical: Producing and transferring disruptive innovation”, The Journal of Technology Transfer, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 663–669.

Cooper, R. G. and Kleinschmidt, E. J. (1993), “Screening new products for potential winners”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 26, No. 6, pp. 74–81.

Delgado-Verde, M., Castro, G. M.-D., and Amores-Salvadó, J. (2016), “Intellectual capital and radical innovation: Exploring the quadratic effects in technology-based manufacturing firms”, Technovation, Vol. 54, pp. 35–47.

Delgado-Verde, M., Castro, G. M.-D., and Navas-López, J. E. (2011), “Organizational knowledge assets and innovation capability: Evidence from Spanish manufacturing firms”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 12, No. 1, pp. 5–19.

Dierickx, I. and Cool, K. (1989), “Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage”, Management Science, Vol. 35, No. 12, pp. 1504–1511.

Dosi, G. (1982), “Technological paradigms and technological trajectories”, Research Policy, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 147–162.

Dumay, J. (2008), “Narrative disclosure of intellectual capital: A structurational analysis”, Management Research News, Vol. 31, No. 7, pp. 518–537.

Dumay, J. (2012), “Grand theories as barriers to using IC concepts”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 4–15.

Dumay, J. (2016), “A critical reflection on the future of intellectual capital: From reporting to disclosure”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 168–184.

Dumay, J. and Rooney, J. (2016), “Numbers versus narrative: An examination of a controversy”, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 202–231.

Dumay, J. and Roslender, R. (2013), “Utilising narrative to improve the relevance of intellectual capital”, Journal of Accounting & Organizational Change, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 248–279.

Dumay, J., Rooney, J., and Marini, L. (2013), “An intellectual capital based differentiation theory of innovation practice”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 608–633.

Ellonen, H.-K. and Karhu, P. (2006), “Always the little brother? Digital-product innovation in the media sector”, International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 83–105.

p.194

European Commission (EC) (2006), RICARDIS: Reporting Intellectual Capital to Augment Research, Development and Innovation in SMEs, European Commission, Directorate-General for Research, Brussels.

Galindo, M-A. and Mendez-Picazo, M-T. (2013), “Innovation, entrepreneurship and economic growth”, Management Decision Vol. 51, No. 3, pp. 501–514.

Gardiner, B. (2008), “Learning from failure: Apple’s most notorious flops”, WIRED, Available at: www.wired.com/gadgets/mac/multimedia/2008/01/gallery_apple_flops, (accessed 27 December 2011).

Gundling, E. (2000), The 3M Way to Innovation, Kodansha International, New York.

Hermans, R. and Kauranen, I. (2005), “Value creation potential of intellectual capital in biotechnology: Empirical evidence from Finland”, R&D Management, Vol. 35, No.2, pp. 171–185.

Hoholm, T. and Araujo, L. (2011), “Studying innovation processes in real-time: The promises and challenges of ethnography”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 40, No. 6, pp. 933–939.

Humphreys, P., Liasides, C., Garcia, L., Roser, T., Viedma Marti, J., and Martins, B. (2010), InCaS: Intellectual Capital Statement Made in Europe, InCAS Consortium, Brussels.

Kay, R. and Goldspink, C. (2013), What Public Sector Leaders Mean When They Say They Want to Innovate, Incept Labs, Sydney.

Kimble, C., Grenier, C., and Goglio-Primard, K. (2010), “Innovation and knowledge sharing across professional boundaries: Political interplay between boundary objects and brokers”, International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 30, pp. 437–444.

Kolleck, N. and Bormann, I. (2014), “Analyzing trust in innovation networks: Combining quantitative and qualitative techniques of social network analysis”, Zeitschrift für Erziehungswissenschaft, Vol. 17, No. 5, pp. 9–27.

Lees T. and Sexton, M. (2014), “An evolutional innovation perspective on the selection of low and zero-carbon technologies in new housing”, Building Research & Information, Vol. 42, No. 3, pp. 276–287.

Leifer, R., McDermott, C., O’Connor, G., Peters, L., Rice, M., and Veryzer, R. (2000), Radical Innovation: How Mature Companies Can Outsmart Upstarts, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Llewellyn, S. (1999), “Narratives in accounting and management research”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 220–237.

Llewellyn, S. (2003), “What counts as ‘theory’ in qualitative management and accounting research? Introducing five levels of theorizing”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 662–708.

Lumkin, G.T and Dess, G.G (2001), “Linking two dimensions of entrepreneurial orientation to firm performance: The moderating role of environment and industry life cycle”, Journal of Business Venturing, Vol. 16, pp. 429–451.

Martín de Castro, G. and López Sáez, P. (2008), “Intellectual capital in high-tech firms: The case of Spain”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 9, No. 1, pp. 25–36.

McGuigan, M. and Henderson, J. (2005), “Organizational strategic innovation: How is government policy helping?”, International Journal of Innovation and Technology Management, Vol. 2, No. 2, pp. 197–215.

Meritum Project (2002), Guidelines for Managing and Reporting on Intangibles (Intellectual Capital Report), European Commission, Madrid.

Mouritsen, J. (2006), “Problematising intellectual capital research: Ostensive versus performative IC”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 820–841.

Mouritsen, J., Bukh, P. N., Flagstad, K., Thorbjørnsen, S., Johansen, M. R., Kotnis, S., Larsen, H. T., Nielsen, C., Kjærgaard, I., Krag, L., Jeppesen, G., Haisler, J., and Stakemann, B. (2003), Intellectual Capital Statements: The New Guideline, Danish Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (DMSTI), Copenhagen.

O’Connor, G. C. and Rice, M. P. (2001), “Opportunity recognition and breakthrough innovation in large established firms”, California Management Review, Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 95–116.

Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) and Statistical Office of the European Communities (Eurostat) (2005), Oslo Manual: Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Innovation Data, Paris.

Paradkar, A., Knight, J., and Hansen, P. (2015), “Innovation in start-ups: Ideas filling the void or ideas devoid of resources and capabilities?” Technovation, Vols 41–42, pp. 1–10.

Pascale, R. T. (1984), “Perspectives on strategy: The real story behind Honda’s success”, California Management Review, Vol. 26, No. 3, pp. 47–72.

p.195

Petty, R. and Guthrie, J. (2000), “Intellectual capital literature review: Measurement, reporting and management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 155–176.

Pitkanen, H. and Lukka, L. (2011), “Three dimensions of formal and informal feedback in management accounting”, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 22, pp. 125–137.

Ratten, V. (2015), “Healthcare organisations innovation management systems: Implications for hospitals, primary care providers and community health practitioners”, International Journal of Social Entrepreneurship and Innovation, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 313–322.

Ripolles, M. and Blesa, A. (2016), “Development of interfirm network management activities: The impact of industry, firm age and size”, Journal of Management & Organization, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 186–204.

Schumpeter, J. A. (1934), The Theory of Economic Development, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Skandia (1996), Power of Innovation: Intellectual Capital Supplement to Skandia’s 1996 Interim Report, Skandia Insurance Company Ltd., Sveavägen 44, SE-103 50 Stockholm.

Smith, J. A., Morris, J., and Ezzamel, M. (2005), “Organisational change, outsourcing and the impact on management accounting”, The British Accounting Review, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 415–441.

Sveiby, K.-E., Gripenberg, P., and Segercrantz, B. (Eds) (2012), Challenging the Innovation Paradigm, Routledge, New York & London.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., and Shuen, A. (1997), “Dynamic capabilities and strategic management”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18, No. 7, pp. 509–533.

Tidd, J. (2001), “Innovation management in context: Environment, organization and performance”, International Journal of Management Reviews, Vol. 3, No. 3, pp. 169–183.

Tidd, J., Bessant, J., and Pavitt, K. (2005), Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester, UK.

Tripsas, M. (2008), “Customer preference discontinuities: A trigger for radical technological change”, Managerial and Decision Economics, Vol. 29, Nos 2–3, pp. 79–97.

Tsai, K. H. and Yang, S. Y. (2013), “Firm innovativeness and business performance: The joint moderating effects of market turbulence and competition”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 42, No. 8, pp. 1279–1294.

Tushman, M. and O’Reilly (1996), “Ambidextrous organizations: Managing evolutionary and revolutionary change”, California Management Review, Vol. 38, No. 4, pp. 36–37.

Weick, K. E. and Browning, L. D. (1986), “Argument and narration in organizational communication”, Journal of Management, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 243–259.