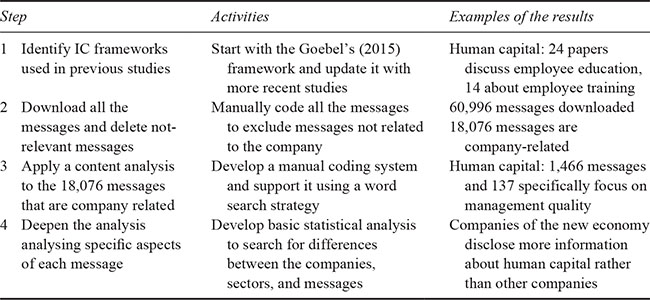

Table 13.1 Methodology followed

p.196

INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL DISCLOSURE IN DIGITAL COMMUNICATION

Maurizio Massaro and John Dumay

Introduction

This chapter contributes to the field of intellectual capital (IC) disclosure by analysing how IC is disclosed in digital communication channels. According to Lipiäinen et al. (2014, p. 276) “literature classifies new digital communications channels in various ways. Recently, the terms ‘social media’ and ‘new media’ have been used to describe a changing communications landscape”. In digital communication, investors who are traditionally considered consumers of information provided by companies now become actors that actively contribute the production and diffusion of such information (Dumay and Guthrie, 2017). Digital communication channels are complex and redefine “the concept of media as a medium that disseminates information” (Zhang, 2016, p. 3). In IC research, most studies examine companies’ traditional approaches to IC disclosure (ICD), and less attention is on new digital communication channels. As Dumay and Cai (2014, p. 276) state “there is a general acceptance of the annual report as the main source of data for analysing ICD, and we note how there is a very little critique of this fact”. Therefore, digital communication channels represent new media where investors discuss IC and represent new venues for ICD.

To explore ICD in digital communication, this study focuses specifically on Internet Stock Message Boards (IMBs) that represent a digital communication channel where investors can discuss specifically listed companies. The study analyses 60,996 messages posted by investors about the top 10 companies by market capitalization listed on the New York Stock Exchange in the period 1 October 2014 to 30 September 2015. Three specific research questions are investigated to understand the key IC elements discussed in IMBs. This study is novel since it focuses on ICD assuming an investor perspective and investigates if and how much investors discuss IC.

Literature review and research questions

The development of the Internet generated a democratization process of information (Jones, 2006) not only for private persons but also for business contexts. Valuable knowledge originally restricted to small privileged groups of people such as bankers and professional investors is now available for a larger part of the business population (Lund and Nielsen, 2017) at a reasonable price or even for free (Ojala, 2006, p. 42). According to Sabherwal et al. (2011, pp. 1209–10): “In addition to trading via online discount brokers, traders often seek information online from paid sources such as ValueLine and Zacks and free sources”. Zhang (2016, p. 9) argues that digital communication channels such as blogs and social media are a good venue for investors to learn about other people’s opinions about securities and markets. The opinions expressed by investors about the future development of the market price is usually called ‘sentiment’, and according to Kim and Kim (2014, p. 708), it has predictive power for stock returns, volatility, and trading volume. Therefore, technology opens new digital communication opportunities for disclosing, discussing, and learning other investors’ opinions about the future stock market price.

p.197

Several digital communication channels such as social media allow users to express their opinion about other messages using tools such as likes and dislikes. Therefore, digital communication channels not only allow investors to express their opinions about specific companies but they also allow investors to comment on other opinions showing agreement or disagreement. As suggested by Berger and Milkman (2012, p. 192) emotional aspects of a message (such as likes and emoticons) may affect whether users share specific messages. Indeed, “People may share emotionally charged content to make sense of their experiences, reduce dissonance, or deepen social connections” (Berger and Milkman, 2012, p. 192). Therefore, the use of specific tools such as like and dislike may affect information sharing processes.

Digital communication channels move the approach from a traditional top-down information scheme to a model that allows companies and investors “to be more interactive, to connect with more people, to be consistent and flexible and to benefit from the opportunity of speed” (Liu and Kop, 2015, p. 128). Traditional approaches consider information to be company owned and require companies to manage and disclose it. For example, Curado et al. (2011, p. 1080) propose a six-step model that enables “firms to more accurately describe their intangible assets”. However, in digital communication, every participant can introduce new information based on direct observation or personal beliefs. Additionally, investors can create discussions using digital communication tools such as blogs and social media to deepen and better understand specific topics. This form of dialogue is thus used by people “to construct versions of the world which are variant, functional and consequential” (Crane, 2012, p. 449). Therefore, digital communication channels provide new and faster ways for companies to disclose information and creates new communities where different actors engage in a discussion that contributes to creating and disseminating information.

Traditional ICD research focuses on company owned information communicated to the market mainly through annual reports (Dumay and Cai, 2014, p. 265). Several studies developed a critique of this approach. For example, Abeysekera (2006, p. 66) observes that few studies acknowledge that annual reports might not reflect the objective reality of the firm. Additionally, Lardo et al. (2017, p. 65) recognize that “annual reports are backward-looking, and contain limited information about the prospects of a company, as would be expected in an IC report”. According to Dumay and Guthrie (2017, p. 30), “How IC information and its communication emanate from sources other than the traditional media associated with a corporation’s IC disclosure and reporting is of growing interest”. Therefore, digital communication channels offer a new perspective to analyse ICD.

Digital communication channels allow for the investigation of investor opinions, measuring topics discussed by investors, measuring their ability to attract attention regarding likes and dislikes, and comparing them with topics analysed and traditionally communicated in annual reports. Scholars use IC research frameworks with checklists of IC related items for analysing the ICD of companies, and some of these frameworks have been reused over time, with some adjustments to adapt them to specific contexts (Goebel, 2015, p. 683). According to Guthrie et al. (2012, p. 76) reusing existing frameworks is a sign that IC research is “maturing and becoming entrenched as a discipline”. The development of digital communication channels allows researchers to compare frameworks developed by scholars using a company oriented perspective to the topics discussed by investors.

p.198

Several recent studies critique the traditional approach to ICD, for example Schaper et al. (2017) and Dumay (2016, p. 168), the latter stating specifically that “IC reporting appears to have died for listed companies. From promising beginnings at Skandia in 1994, I can no longer find any evidence of listed companies reporting their IC”. Similarly, Abeysekera (2006, p. 66) states “most listed firms use the annual report as a document to publicise the firm rather than as merely a way of complying with accounting standards and corporate law”. However, digital communication channels have generated relevant changes in the way companies and investors interact (Pisano et al., 2017, p. 102) providing new opportunities of ICD that need to be addressed. Moving from this premise we draw our general research question:

RQ: What are the key IC elements discussed in digital communication channels?

To answer the general research question, we want to focus on three main aspects of ICD in digital communication channels:

RQ 1. How much is IC discussed in digital communication channels?

RQ 2. What is the difference between traditional ICD frameworks and investors’ discussions?

RQ 3. In which way is ICD used by investors to justify their sentiment?

Methodology

Research context

To analyse ICD in digital communication channels, we focus on IMBs that represent online communities where investors discuss specific companies listed on stock exchanges. IMBs are normally distinguished in topic-generic and topic-specific message boards (also known as stock trading boards and trading boards, respectively) (Zhang, 2016, pp. 27–32). In topic-generic message boards, messages are shown in chronological order and focus on all companies (Zhang, 2016, pp. 27–32). Examples are TheLion,1 HotCopper,2 and Trade2Win.3 By contrast, topic-specific message boards mainly focus on target companies, and therefore discussions are organized by the company itself. Examples are Yahoo! Finance Message Board4 and Raging Bull.5 Focusing on the different message boards, Sabherwal et al. (2011, p. 1210) report that TheLion attracts more than 250 million monthly page views. Similarly, focusing on Yahoo Message Board, Das and Chen (2007, p. 1375) report the high growth in the number of messages on this platform. Therefore, this chapter uses Yahoo Message Board and TheLion as important IMBs to study.6

Within the IMBs sources, this chapter analyses the ten most capitalized companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange: Apple, Microsoft, Walmart, IBM, JP Morgan, Oracle, Alphabet, Pfizer, Citigroup, and BP. For each company, we develop and use a web-scrapping script to download messages posted in a one-year period from 1 October 2014 to 30 September 2015, resulting in 60,996 messages. The downloaded messages are first included in an Excel spreadsheet and then imported into the software NVivo for coding. For each company the following details are obtained: title, text, author, date of posting, number of likes and dislikes, and sentiment provided (e.g. sell, buy, hold).

p.199

Data analysis

To answer the research questions, this chapter employs a mixed method approach first based on a content analysis to determine if the messages contain any IC information (Krippendorff, 2013), and then we develop quantitative analysis on the messages coded. To conduct the analysis, we follow four main steps.

First, we define the framework representing the analytical construct to develop the content analysis. According to Krippendorff (2013, p. 40), “analytical constructs operationalize what the content analysis knows about the context, specifically, the network of correlations that are assumed to explain how available texts are connected to the possible answers to the analyst’s questions”. To analyse existing frameworks, this study focuses on papers published in previous peer-reviewed journals. This analysis builds on the framework presented by Goebel (2015, p. 686). We updated the original framework adding recent studies not considered at the time of the original framework. According to Goebel (2015, p. 681) “widely used IC items capture the majority of IC reporting”. Therefore, this study relies on previous studies on ICD to measure the key IC topics discussed by the literature.

Second, we performed an extensive coding of all the messages. According to Krippendorff (2013, p. 127) “coding is the term content analysts use when this process is carried out according to independent observer rules”. Due to the high number of messages, we trained a group of young researchers to code the messages. A manual coding selection was developed on the total of 60,996 messages downloaded to delete irrelevant or only market focus messages. As a result, we selected 18,076 messages representing 30 per cent of the whole sample.

Third, we focused on the 18,076 relevant messages applying the ICD framework developed at step one. To assure reliability of results, one author independently performed a computer-aided coding based on a “word search” and results were compared to the manual coding to calculate the Krippendorff’s Alpha. According to Krippendorff (2013, p. 325) researchers can “rely only on variables with reliability above a = 0.800; consider variables with reliabilities between 0.667 and a = 0.800 only for drawing tentative conclusions”. The results of this analysis show a Krippendorff’s Alpha over 0.8 in all instances, and therefore we claim reliability of the results.

Table 13.1 Methodology followed

p.200

Fourth, we use the results of the content analysis to develop descriptive statistics. More precisely, findings of the ICD framework discussed within the literature are compared to the content analysis of the relevant messages. The main differences are discussed, searching for differences between items discussed by investors and items analysed by the literature.

Fifth, results are deepened focusing on some specific aspects such as differences between companies belonging to different sectors and the ability of the ICD messages to attract likes. Table 13.1 summarizes the steps of the analysis.

Findings

This section presents the main results of the analysis. The first subsection presents results of the content analysis with the aim of answering RQ1: How much is IC discussed in digital communication channels? The second subsection deepens the analysis focusing specific items for each IC component with the aim of answering RQ 2: What is the difference between traditional ICD frameworks and investors’ discussions? The third subsection presents some further insights with the aim of answering RQ 3: In which way is ICD used by investors to justify their sentiment?

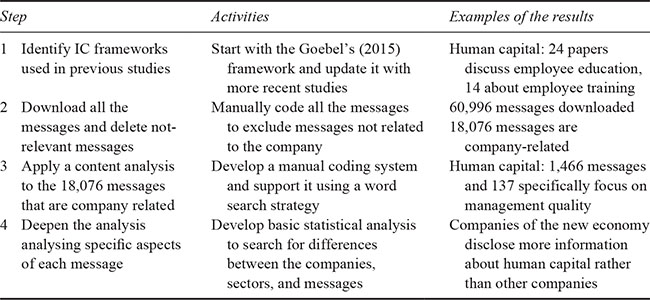

RQ 1: IC discussions in IMBs

This subsection provides descriptive statistics about the ICD. The results depicted in Table 13.2 show that IMBs are widely used by investors who posted 60,996 messages, but only 18,076 messages focus on the company. The majority of the messages are general discussions on the stock price, the stock market, or out of topic. Focusing only on company-based messages, Table 13.2 shows that 14 per cent of the messages contain ICDs with 2,581 messages. Interestingly, 1,466 (57 per cent) messages contain discussions on relational capital. Flöstrand (2006, p. 457) finds similar results in the analysis of 250 financial analyst reports of randomly selected S&P 500 companies. Therefore, relational capital is widely discussed in IMBs and widely disclosed in analyst reports.

Our sample companies arise from more innovative sectors usually connected with the new economy rather than more traditional sectors. According to Lohr (2001, p. 1) the term new economy, is “a symbolic shorthand for the power of technology to transform the economy, investment strategy, business thinking, even modern culture”. Businessdictionary.com refers to the new economy as being strongly connected with ICT7 and usually labelled high-tech companies. Following this definition, in our sample, Apple, IBM, Oracle, Microsoft, and Google are considered high-tech companies.

Findings show that 37 per cent of the messages of high-tech companies (respectively: 38 per cent for Apple, 33 per cent for Microsoft, 44 per cent for Oracle, and 31 per cent for Google) discuss structural capital, while the total average is only 27 per cent. Thus, investors discuss more structural capital when high-tech companies are analysed. Similarly, Dumay and Tull (2007, p. 250) find that structural capital information has a different impact on stock prices when compared to other disclosures. Therefore, high-tech companies that produce higher ICD on structural capital can potentially have a relevant impact on stock prices.

p.201

Table 13.2 Descriptive statistics for ICD in IMBs

Note. The sum of human capital, relational capital and structural capital can be different from the sum of IC since one message coded as IC could have one or more IC determinants.

To test the validity of these results, we performed a logistic regression with the dependent variable being the ICD based only on structural capital, and the independent variable being the fact that the company belongs to the new economy group. Results confirm that in IMBs, messages of high-tech companies have a higher probability of containing structural capital information compared to low-tech companies with a p-value of less than 0.001. These results build on Abdolmohammadi (2005, p. 412) who states that:

[t]he new economy sector discloses more about its intellectual property and information systems categories than the old economy sector … [and this] may indicate that the companies in the new economy either possess more of these IC categories or are more willing to disclose them.

The higher level of discussions based on structural capital suggests that investors perceive this element as more important for these companies.

Additionally, Table 13.2 shows that innovative firms based on the new economy show a lower level of ICD based on human capital. To test the validity of these results, we performed a logistic regression with ICD based on human capital as the dependent variable and the fact that the company belongs to the new economy group as the independent variable. Results confirm with a p-value of less than 0.001 that companies of the new economy disclose less information about human capital compared to other companies These results contradict Bellora and Guenther’s (2013, p. 265) findings where “Human capital is the category with most INC [Innovation Capital Disclosure]”. As suggested by Alex Mandl, interviewed by Carey (2000, p. 146), “the plain fact is that acquiring is much faster than building. And speed – speed to market, speed to positioning, speed to becoming a viable company – is essential in the new economy”. According to Geis (2015, p. 42), Google and Apple and other players such as Facebook, Yahoo!, and Microsoft will join in an acquisition fray and engage in many responsive merger and acquisition operations. Therefore, these results suggest that investors could be less interested in human capital, and more in companies with a strong merger and acquisition strategy such as Google, Apple, and Microsoft.

p.202

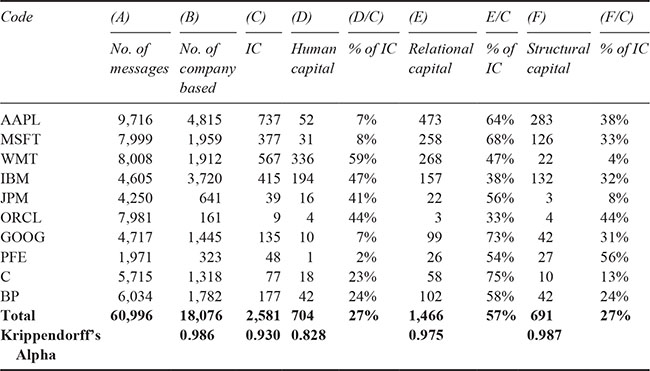

RQ 2: IC items discussed in IMBs

Focusing on the IC elements results show that there is a discrepancy between the most analysed IC items depicted in Table 13.2 and the most discussed IC items in IMBs. Figure 13.1 depicts the main findings and shows the most important items comparing how much an item is used in previous studies and how much the item is discussed within IMBs. The main differences are connected with human capital. While items such as training, employee retention, and skills are heavily used by scholars in previous studies, they are barely discussed in IMBs. More precisely, comparing the two groups, items that are commonly used in at least ten studies of the total of 37 studies analysed, count for less than 10 per cent of all the items discussed in human capital ICD, 51 per cent of all the items discussed in relational capital ICD, and 31 per cent of all the items discussed in structural capital ICD. Therefore, results show that shared items that see scholars in agreement about their importance regarding ICD, account for a minimal part of the whole discussion about ICD.

Figure 13.1 Comparison between the relevance of IC Items found in the analysis and in previous ICD studies

Items recognized only by some scholars and that do not show agreement among scholars about their relevance to IC still account for a large part of ICD. Some of the most under-considered items are management quality, market share, and new products. These results confirm the findings of Sakakibara et al. (2010) and Abhayawansa and Guthrie (2014), who focus on analyst’s needs and find that several types of IC information had not been examined previously in capital markets research. Additionally, ICD not focused on investors’ needs can be detrimental to market functioning. Indeed, according to Nielsen et al. (2015, p. 83), “the efficient functioning of capital markets is dependent upon the flow of information between companies and investors, either directly or indirectly through financial intermediaries”.

p.203

The above results build on Goebel’s (2015, p. 693) findings where “companies seem to focus on the same widely used IC items as IC researchers because corporate IC reporting mainly refers to these items for each IC category”. However, most of the items used for developing previous research are for analysing annual reports. As Dumay (2016) states “it is highly unlikely that any information contained in the annual report would be price-sensitive because annual reports detail periodic rather than current information”. IMBs are “closely watched by investors who seek inputs to enhance their trading profits” (Sabherwal et al., 2011, p. 1210). Therefore, investors widely discuss new products or figures about market share because it is more price-sensitive information in comparison to information about employee training or retention. These results confirm Holland’s (2003, p. 42) observation “that qualities of key executives, and changes in top management, have affected stock prices” and call for a re-discussion of top IC items in ICD.

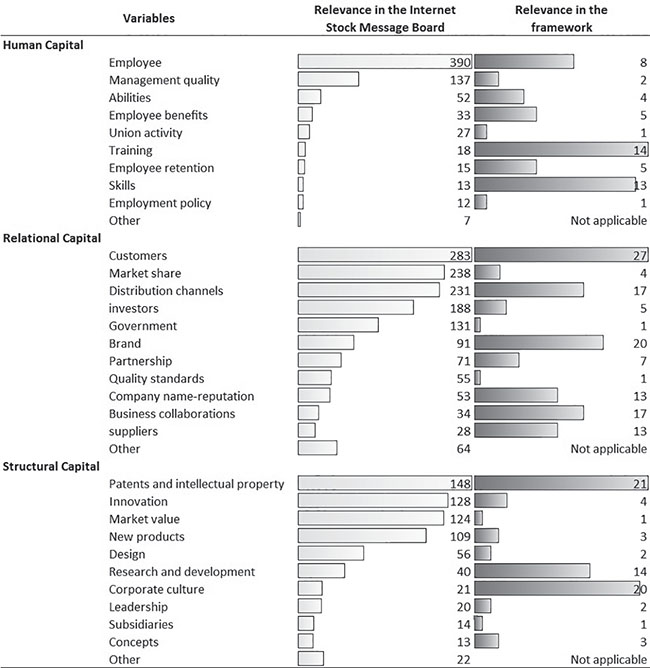

RQ 3: IC disclosure and sentiment provided

Focusing on the role of ICD in justifying the sentiment provided (e.g. buy, hold, sell), the results show that 9,071 messages provide a sentiment that represents 18 per cent of all messages. Additionally, results show that there is a statistical significance difference between messages that provide sentiment and messages that do not provide it. IC focused messages show that 22 per cent of the messages provide investor’s sentiment (e.g. buy, hold, sell) while only 15 per cent of the messages that do not contain IC information provide investor’s sentiment. To test differences, we perform a statistical test developed using a logistic regression with the dependent variable a dummy variable (1 if the messages provide sentiment and 0 if it does not) and the independent variable the fact that the message contains IC (1 if the messages contain ICD and 0 if it does not). Findings show that with a p-value less than 0.001, messages that contain IC have a probability higher than 63 per cent of providing sentiment. Therefore, investors refer to IC to justify their opinion about the future development of company’s stock market prices. IC determinants are therefore more important than other elements not related to IC to justify investor opinions about the future development of company’s share price.

In addition, findings show that ICD is used to justify sell or buy sentiment rather than hold. Even though there is not a statistically significant difference among sell and buy, “strong sell” and “strong buy” together account for more than 84 per cent of the total ICD messages with sentiment. These results confirm Kim and Kim’s (2014, p. 712) findings that “retail investors tend to reveal extreme sentiments such as Strong Buy and Strong Sell rather than moderate sentiments such as Buy and Sell”.

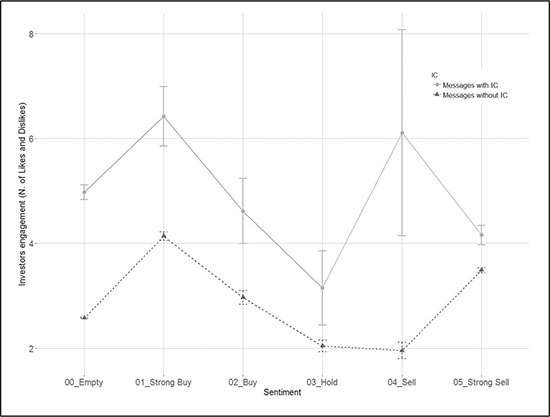

Finally, in IMBs investors can comment on other investors’ messages and express their agreement or disagreement expressing likes and dislikes. Likes and dislikes show how much investors are involved in specific discussions. Results show that investors react more to strong sentiment (e.g. strong buy or strong sell) with higher levels of likes and dislikes. Additionally, our analysis shows that messages that contain ICD are more able to attract discussions with a higher level of likes or dislikes expressed by other investors independently by the sentiment expressed (buy, hold, or sell). Therefore, the results show that investors are more engaged in messages that contain ICD considering both positive sentiments (buy and strong buy), negative sentiments (sell and strong sell), or neutral sentiment (empty or hold). Figure 13.2 depicts the main findings.

p.204

Figure 13.2 ICD and message engagement

Discussion

This chapter contributes to the field of IC by analysing the role of stock message boards for disclosing IC as a new form of digital communication. Following this premise, this research allows the building of some implications for ICD research.

Implication 1. Digital communication channels provide new venues to disclose IC

According to Bismuth and Tojo (2008, p. 242), “providing the market with sufficient and appropriate information about intellectual assets improves decision-making by investors and helps discipline management and boards with positive economic consequences”. The study investigates an alternative form of disclosure in IMBs, not traditionally analysed in the IC literature.

Analysing alternate forms of disclosure is important because, as Dumay (2016, p. 168) outlines, there is no “evidence of listed companies reporting their IC”. Furthermore, the most traditional document used in ICD research is the annual report, and this document is not designed to include ICD and is arguably used in ICD research because few, if any, IC reports exist (Dumay and Cai, 2014). Additionally, IC reports and/or disclosures that emanate from the company are often biased, focusing on good news, and thus cannot be trusted as a reliable source of ICD. Therefore, we need to uncover company unbiased sources of ICD to understand how IC information affects investor decision-making processes because annual reports are not the sole source of information for investors. IMBs offer the potential to give us company unbiased information because the posts are not created by the companies, but rather by investor participants of the IMBs

p.205

The most significant aspect of the messages posted in IMBs is that they are an example of what Dumay and Guthrie (2017) call ‘involuntary disclosure’, whereby the messages are created by external stakeholders who disclose information about a company. Therefore, unlike traditional ICD research, which examines company-created and voluntary ICD, we can now analyse the response to company ICD through these messages. Examining messages from market participants is important because ICD research has always espoused the benefits of ICD, but few studies have ever analysed the response to IC reporting and disclosure (Abhayawansa and Abeysekera, 2009; Abhayawansa, 2011; Abhayawansa and Guthrie, 2012).

Implication 2. IC disclosure should focus on investor IC needs rather than perpetuating existing frameworks

The results of this study show that IC is an important topic discussed in IMBs. Interestingly, specific topics discussed by investors do not match frameworks previously published in ICD research. While some elements strongly discussed in previous studies, such as employee skills, are barely discussed by investors, other elements, such as management quality, are heavily commented on. Therefore, the results of this study show the need to update current frameworks on ICD, since some topics are less discussed within the literature but are heavily considered by investors.

According to Guthrie et al. (2012, p. 76), reusing existing frameworks is a sign that IC research is maturing as a research field. However, when frameworks do not focus on investors’ information needs, there is a divide between IC research that produces research knowledge and stakeholders that use that knowledge. Therefore, several studies claim the existence of an academic–practitioner divide (Wofford and Troilo, 2013, p. 41), with academics sometimes closed in their ivory towers (Cuozzo et al., 2017, p. 9) ignoring innovation provided by digital communication channels. The results of this study provide evidence that there are new ways for companies and investors to discuss IC and that IC researchers should question existing frameworks rather than perpetuate existing models.

Implication 3. IC disclosure should focus on different company characteristics since one suit does not fit all

Our findings show that within companies that belong to different industries, ICD is differently discussed by investors. Indeed, human capital is less discussed in very dynamic sectors such as in the new economy-based companies. The need to acquire and adapt makes other IC elements, such as relational capital, more relevant to investors. Therefore, ICD frameworks cannot be drawn without considering the specific sector in which the company operates.

According to Ardley (2008, p. 533), “Scholars desire to reduce real world activity to overarching explanations has led to the simplification of theory”. Understanding “how IC works” (Dumay and Garanina, 2013, p. 20) requires developing focused analysis avoiding the risk of developing “grand theories” (Dumay, 2012), suggestive for scholars but hardly useful for practitioners. As a result of this divide according to Van De Ven and Johnson (2006, p. 802), “academic research has become less useful for solving practical problems and [therefore] the gulf between theory and practice in the professions is widening”. Results of this study show that ICD cannot be drawn without considering the specific industrial sector where the companies analysed work. Therefore, for researchers to adapt their ICD research strategy, as well as managers, they need to adapt their ICD models to address the specific needs of investors.

p.206

Implication 4. IC disclosures as not only roses and sunshine

Results show that ICD discussed by investors has an important impact on the sentiment provided. Interestingly, IC information is used by investors to disclose sentiment to buy, hold, or even sell. These results build on Santis and Giuliani’s findings that investing in IC has both negative and positive effects and therefore ICD is not all sunshine and roses. The results show that investors are worried not only about the wealth creation myth but also with the idea of wealth destruction and intellectual risks or obligations (Santis and Giuliani, 2013, p. 213).

According to Dumay (2013, p. 7), “managers must monitor and manage intellectual liabilities to control the possible negative effects generated by IC”. Results show that investors carefully discuss these topics and use ICD to justify critical positions such as sell or strong sell. Interestingly, as suggested by Dumay and Cai (2014, p. 276), managers tend to overlook negative effects and therefore understanding intellectual liabilities in traditional communication channels is difficult. Digital communication channels such as IMBs offer new opportunities to investigate these intellectual liabilities.

Conclusion

In concluding this chapter, we recall some of the reasons that motivated it. This chapter starts with the observation that digital communication channels provide new venues for ICD. The paper focuses on IMBs analysing 60,996 messages posted on two message boards in one year for the 10 most capitalized companies on the New York Stock Exchange. The high number of messages confirms that investors use new media to acquire, discuss, and share information about companies. Interestingly, discussions concentrate on different IC elements according to the sector of the company. More precisely, our results show that high-tech companies are more focused on relational capital and less on human capital. Additionally, the findings show that topics discussed by investors do not match previous frameworks used in ICD research. Indeed, some topics highly discussed by scholars are almost ignored by investors (e.g. employee training) and others almost ignored by scholars are heavily discussed by investors (e.g. management quality). Finally, the results show that messages that contain ICD more likely disclose investor’s sentiment (e.g. hold, buy, or sell), showing that IC matters to investors and is often used to justify their opinion about a company’s future.

The study has several implications for practitioners. First, IMBs represent an interesting discussion arena. Managers can understand market concerns about a company’s IC by analysing investors’ discussions. By understanding what users talk about in IMBs, managers can see if and how the information about their company’s IC is received by investors. Additionally, executives can analyse the main doubts expressed by investors and therefore analyse the effectiveness of their communication. In other words, through IMB analysis, managers can understand the long- and short-term impact of ICD. Managers should consider that ICD is evolving and social media offers new ways to communicate. This moves communication from a traditional one-way top-down communication (where managers communicate things to the market) to a more complex process. Technology provides new ways to analyse text, and text mining projects can help managers in understanding investors’ doubts and beliefs. Automated tools for theme extraction and semantic analysis could be added or used. These tools can help managers in making sense of investors’ perceptions of IC. In this context, ICD is moving from a one-way communication approach to an interactive approach, where the doubts of the market are analysed by managers, and ICD and company communications are consequently adjusted.

p.207

Second, IMBs, like many new digital communication tools, allow users to express their engagement, posting comments to messages, and likes or dislikes. This interaction provides the opportunity to influence other investors’ perceptions. Indeed, according to Roelens et al. (2016, p. 25), there is a “growing acceptance of the fact that people are highly influenced by information received from others”. Communication in social media assumes new ways and can be affected by specific users called a “social media influencer” (Freberg et al., 2011, p. 90). Managers should analyse the behaviours of these social media influencers who with their opinions can influence other behaviours.

Third, the ability for social media to influence investors has also gained the attention of regulators. For example, in the US, the Securities Exchange Commission (SEC) is monitoring social networks and has charged several brokers for posting fake information on IMBs to manipulate stock prices (SEC, 2009). However, digital communication tools provide new ways to also influence others without posting fake information. Besides the social media influencers, Zhang (2016, pp. 42–55) identifies a subgroup of investors that use IMBs called ‘trolls’ who repeatedly and deliberately break the etiquette by posting inflammatory, extraneous, and off-topic messages. Those users can lead discussions and contribute to shaping investors’ opinions even without posting fake information. Based on our findings, we argue that regulators should extend their monitoring activity on IMBs, not only focusing on the communication of false information to prevent potential frauds (e.g. pump and dump schemes)8 but also consider the role of social media influencers and trolls.

Fourth, the results can be used by IMB managers. Considering the high number of messages posted, investors need to find a way to filter relevant messages ignoring the noise produced by off-topic or not-company-based messages. At present, search tools of most of the IMBs are very basic. Therefore, developing new methods for filtering messages (e.g. by sentiment provided, by the number of likes or dislikes) could help investors to search for specific messages.

This research opens new research opportunities. First, this study focuses only on variables that affect ICD. New research lines could focus on the impact that IMBs have on the market, such as the relationship between ICD and market volatility or stock market prices. Second, new perspectives could be derived from event studies (e.g. Dumay and Tull, 2007). For example, new research lines could analyse how IMBs react to specific price-sensitive information delivered to the market. Third, the role of users could be deepened to include interviews to understand their motivation to post information and their actual ability to influence market prices. Fourth, IMBs are only one of the new social media tools available in the market. For example, micro-blogging using Twitter is another example of a social media tool that can be considered to expand upon, and compare with, the findings of this study.

To conclude this chapter, it is important to point out that this study has its limitations. First, considering the high number of messages, this study focuses only on ten companies for one year. Several extraordinary political and catastrophic events happened during the period of analysis (e.g. the Greek debt crisis, the immigrant crisis, and other mass media events), as well as company related events (e.g. the launch of new products for one company), which could have influenced the results of the analysis. Additionally, subjectivity in applying manual content analysis should be considered. To confirm these results, this study should be repeated in the future. Additionally, this study focuses on companies listed on the New York Stock Exchange with a high capitalization, a dimension that could affect the results, and thus we could also extend this study to smaller companies, and companies listed in different countries.

p.208

Notes

1 See www.thelion.com/ (accessed 19 April 2016).

2 See http://hotcopper.com.au/postview (accessed 19 April 2016).

3 See www.trade2win.com/boards/ (accessed 19 April 2016).

4 See, for example, http://finance.yahoo.com/mb/YHOO/ (accessed 19 April 2016).

5 See http://ragingbull.com/ (accessed 19 April 2016).

6 Since the beginning of this study in 2015, TheLion has introduced new features to the platform. TheLion now collects messages from all other IMBs, becoming a Board of Boards (Zhang, 2016). At the time of the last access on 24 April 2016 the old functions were still available under the menu Forum on the platform. Results discussed in this chapter refer to the old version of the platform.

7 See: www.businessdictionary.com/definition/new-economy.html (accessed 22 August 2016).

8 A pump and dump scheme works by pumping the market with false information to dump it when the maximum price is reached (Zhang, 2016).

References

Abdolmohammadi, M. J. (2005), “Intellectual capital disclosure and market capitalization”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 397–416.

Abeysekera, I. (2006), “The project of intellectual capital disclosure: Researching the research”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 61–75.

Abhayawansa, S. (2011), “A methodology for investigating intellectual capital information in analyst reports”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 446–476.

Abhayawansa, S. and Abeysekera, I. (2009), “Intellectual capital disclosure from sell-side analyst perspective”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 294–306.

Abhayawansa, S. and Guthrie, J. (2012), “Intellectual capital information and stock recommendations: Impression management?”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 13, No. 3, pp. 398–415.

Abhayawansa, S. and Guthrie, J. (2014), “Importance of intellectual capital information: A study of Australian analyst reports”, Australian Accounting Review, Vol. 24, No. 1, pp. 66–83.

Ardley, B. (2008), “A case of mistaken identity: Theory, practice and the marketing textbook”, European Business Review, Vol. 20, No. 6, pp. 533–546.

Bellora, L. and Guenther, T. W. (2013), “Drivers of innovation capital disclosure in intellectual capital statements: Evidence from Europe”, The British Accounting Review, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 255-270.

Berger, J. and Milkman, K. L. (2012), “What makes online content viral?”, Journal of Marketing Research, Vol. 49, No. 2, pp. 192–205.

Bismuth, A. and Tojo, Y. (2008), “Creating value from intellectual assets”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 9, No. 2, pp. 228–245.

Carey, D. (2000), “Lessons from master acquirers: A CEO roundtable on making mergers succeed”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 78, No. 3, pp. 145–154.

Crane, L. (2012), “Trust me, I’m an expert: Identity construction and knowledge sharing”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 448–460.

Cuozzo, B., Dumay, J., Palmaccio, M., and Lombardi, R. (2017), “Intellectual capital disclosure: A structured literature review”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 9–28.

Curado, C., Henriques, L., and Bontis, N. (2011), “Intellectual capital disclosure payback”, Management Decision, Vol. 49, No. 7, pp. 1080–1098.

Das, S. R. and Chen, M. Y. (2007), “Yahoo! for Amazon: Sentiment extraction from small talk on the web”, Management Science, Vol. 53, No. 9, pp. 1375–1388.

p.209

Dumay, J. (2012), “Grand theories as barriers to using IC concepts”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 4–15.

Dumay, J. (2013), “The third stage of IC: Towards a new IC future and beyond”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 5–9.

Dumay, J. (2016), “A critical reflection on the future of intellectual capital: From reporting to disclosure”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 168–184.

Dumay, J. and Cai, L. (2014), “A review and critique of content analysis as a methodology for inquiring into IC disclosure”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 264–290.

Dumay, J. and Garanina, T. (2013), “Intellectual capital research: A critical examination of the third stage”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 10–25.

Dumay, J. and Guthrie, J. (2017), “Involuntary disclosure of intellectual capital: Is it relevant?”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 29–44.

Dumay, J. and Tull, J. A. (2007), “Intellectual capital disclosure and price-sensitive Australian Stock Exchange announcements”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 236–255.

Flöstrand, P. (2006), “The sell side: Observations on intellectual capital indicators”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 457–473.

Freberg, K., Graham, K., McGaughey, K., and Freberg, L. A. (2011), “Who are the social media influencers? A study of public perceptions of personality”, Public Relations Review, Vol. 37, No. 1, pp. 90–92.

Geis, G. T. (2015), Semi-Organic Growth: Tactics and Strategies Behind Google’s Success, Wiley, London.

Goebel, V. (2015), “Is the literature on content analysis of intellectual capital reporting heading towards a dead end?”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 681–699.

Guthrie, J., Ricceri, F., and Dumay, J. (2012), “Reflections and projections: A decade of intellectual capital accounting research”, The British Accounting Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 68–82.

Holland, J. (2003), “Intellectual capital and the capital market. Organisation and competence”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 39–48.

Jones, L. A. (2006), “Have internet message boards changed market behavior?”, Info, Vol. 8, No. 5, pp. 67–76.

Kim, S.-H. and Kim, D. (2014), “Investor sentiment from internet message postings and the predictability of stock returns”, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, Vol. 107, pp. 708–729.

Krippendorff, K. (2013), Content Analysis. An Introduction to Its Methodology, Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA.

Lardo, A., Dumay, J., Trequattrini, R., and Russo, G. (2017), “Social media networks as drivers for intellectual capital disclosure. Evidence from professional football clubs”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 63–80.

Lipiäinen, H. S. M., Karjaluoto, H. E., and Nevalainen, M. (2014), “Digital channels in the internal communication of a multinational corporation”, Corporate Communications: An International Journal, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 275–286.

Liu, R. and Kop, A. E. (2015), “The usege of social media in new product development process”, in Hajli, N. (Ed.), Handbook of Research on Integrating Social Media into Strategic Marketing, IGI Global, New York, pp. 120–135.

Lohr, S. (2001, 8 October), “The new meaning of new economy”, New York Times, pp. 1–5.

Lund, M. and Nielsen, C. (2017), “Making intellectual capital matter to the investment community”, in Guthrie, J., Dumay, J., Ricceri, F., and Nielsen, C. (Eds), The Routledge Companion to Intellectual Capital, Routledge, London, pp. 435–449.

Nielsen, C., Rimmel, G., and Yosano, T. (2015), “Outperforming markets: IC and the long-term performance of Japanese IPOs”, Accounting Forum, Vol. 39, No. 2, pp. 83–96.

Ojala, M. (2006), “Finance portals and their impact on information professionals”, The Dollar Sign, pp. 42–44.

Pisano, S., Lepore, L., and Lamboglia, R. (2017), “Corporate disclosure of human capital via LinkedIn and ownership structure: An empirical analysis of European companies”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 102–127.

Roelens, I., Baecke, P., and Benoit, D. F. (2016), “Identifying influencers in a social network: The value of real referral data”, Decision Support Systems, Elsevier B.V., Vol. 91, pp. 25–36.

Sabherwal, S., Sarkar, S. K., and Zhang, Y. (2011), “Do internet stock message boards influence trading? Evidence from heavily discussed stocks with no fundamental news”, Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, Vol. 38, No. 9–10, pp. 1209–1237.

p.210

Sakakibara, S., Hansson, B., Yosano, T., and Kozumi, H. (2010), “Analysts’ perceptions of intellectual capital information”, Australian Accounting Review, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 274–285.

Santis, F. De and Giuliani, M. (2013), “A look on the other side: Investigating intellectual liabilities”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 212–226.

Schaper, S., Nielsen, C. and Roslender, R. (2017), “Moving from irrelevant intellectual capital (IC) reporting to value-relevant IC disclosures: Key learning points from the Danish experience”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18 No. 1, pp. 81–101.

SEC (2009), “SEC charges New York broker for manipulating stock prices through fake press releases and internet postings”, Press Release.

Van De Ven, A. H. and Johnson, P. E. (2006), “Knowledge for theory and practice”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 802–821.

Wofford, L. and Troilo, M. (2013), “The academic-professional divide: Generating useful research and moving it to practice”, Journal of Property Investment & Finance, Vol. 31, No. 1, pp. 41–52.

Zhang, Y. (2016), Stock Message Boards. A Quantitative Approach to Measuring Investor Sentiment, Palgrave Macmillan, New York.