Figure 15.1 Integrated framework for competitive advantage, strategy, and IC management

p.236

SUSTAINED COMPETITIVE ADVANTAGE AND STRATEGIC INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL MANAGEMENT

Evidence from Japanese high performance small to medium sized enterprises

Jun Yao and Chitoshi Koga

Introduction

Intellectual capital (IC) management is not new to Japanese companies. Japan has a long-term commitment to the resource-based view, with Itami’s (1987) Mobilizing Invisible Assets one of the earliest and most significant contributions to IC research (Sullivan, 2000). Later, Nonaka and Takeuchi’s (1995) The Knowledge-Creating Company promoted interest in Japanese style knowledge management (KM). However, the IC and KM literature, including these well-known works, mostly focus on large companies. Previous studies have identified that small to medium sized enterprises (SMEs) manage IC in a different way from large companies (Hutchinson and Quintas, 2008; Demartini and Del Baldo, 2015; Marzo and Scarpino, 2016). SMEs have also attracted less research interest, despite being economically important – in Japan 99.7 per cent of companies are SMEs.

However, in recent years, Japan has been involved in initiatives to promote a new model of growth, which places high-value-added intangible assets or IC at its core. In 2005, the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry of Japan (METI) published the first guidelines for IC management reporting. In the following years, IC policies were developed and in some regions (Kansai Area) or prefectures (Kyoto Prefecture), local governments promoted IC management, reporting, and financing especially for SMEs.

Japanese IC management differs from that in western countries (Uchida and Roos, 2008), while the IC reporting models recommended by the Japanese government are borrowed from western countries. Japanese organizations often find preparing IC reports based on western models difficult and Japanese financial institutions, despite acknowledging IC as critical to value creation, find it difficult to evaluate IC. There is a lack of understanding of IC management and its relationship to firm performance among managers, investors, and other stakeholders. It is against this background that this chapter attempts to analyse the third stage of IC research – how organizations implement IC in practice from a critical and performative perspective (Guthrie et al., 2012; Dumay and Garanina, 2013) – and how IC management is implemented in practice in Japanese SMEs. We analyse five case companies over ten years to explore how IC contributes to sustained competitive advantage.

p.237

Ricceri (2008) called for the integration of strategitization into IC management. Strategy is thought to affect developing IC, which affects how an SME performs (Cohen et al., 2014), thus, “discussing strategy helps with understanding how IC practices contribute to competitive advantage” (Dumay and Guthrie, 2012). Also, the new reporting initiative, Integrated Reporting, suggests disclosing strategy to help information users understand sustainable value creation (IIRC, 2013). Therefore, we focus our analysis on the strategy and compare ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ to find out whether these companies strategically manage IC and how they formulate strategies and convert IC into competitive advantage and improved performance.

Theoretical framework and key concepts

Although the resource-based view regards the organization as a bundle of resources, not all businesses with superior capabilities and resources can obtain improved market position and performance. For example, some famous companies like Sharp, despite owning numerous technology and patents, faced a crisis in recent years. How IC contributes to sustained competitive advantage remains in the ‘black box’. To analyse and compare the case companies, we utilize a framework constructed based on a review of the strategy literature. The key terms used in the framework, such as competitive advantage, capabilities, and resources including IC and strategy (both competitive strategy and KM strategy), will be defined and explained.

Framework used for analysis

There is no widely accepted definition of competitive advantage in the practice and management literature. Some research focuses on the relative advantage of the market position, and high performance is thought to be gained by providing customers with products of higher quality, better design, faster service, or at a lower cost (Porter, 1985). Some research focuses on the sources of competitive advantage, which is defined as relative superiority in terms of capabilities and resources. For example, Coyne (1986) considers the sources of competitive advantage to be: positional, for example, customer loyalty as a result of past action; regulatory or legal entities such as patents and contracts; functional, which is created from the competence of employees and others in the value chain; and cultural, which comprises, for example, organizational habits, attitudes, beliefs, and value. Others focus on more specific KM factors, connecting KM to innovation, which in turn leads to competitive advantage (Egbu et al., 2005; Lee et al., 2016).

Day and Wensley (1988) argue that none of the above views provides a whole picture; rather, combined they define both the state of competitive advantage and the process of how it is gained. Therefore, he proposed an integrative framework connecting capabilities, resources, position, and performance for diagnosing competitive advantage. In this study, we adopt an integrated framework as shown in Figure 15.1 based on Day and Wensley (1988), but expand it to enable more detailed analysis of IC management. The key components of the framework such as positional and performance superiority (results of IC management), superior capabilities and resources (source of competitive advantage), and strategy (what leads IC to competitive advantage) are explained in the following section (Day and Wensley, 1988; Barney, 1991; Rangone, 1999; Takahashi, 2012; Lee et al., 2013).

p.238

Figure 15.1 Integrated framework for competitive advantage, strategy, and IC management

Key components of the framework

Positional and performance superiority

Competitive advantage is often demonstrated as superiority in market position. In an existing market, the company’s relative superior position may be represented either as the cost edge or the differentiation in product function, branding, reputation, or business model, or a new market based on current technology. It may also refer to an expanding market based on revolutionary technology (Takahashi, 2012). SMEs’ strategic position may affect the composition of IC either developed or acquired (Aragón-Sánchez and Sánchez-Marín, 2005; St-Pierre and Audet, 2011). There are many ways to measure performance. Superior performance may refer to high growth rate, profit, or market share. In the case of SMEs, long-term survival can also be regarded as superior performance because, according to the Teikoku Databank, the average life span of an SME is 30 years. Many SMEs, instead of focusing on growth, see longevity as their primary goal.

Superior capability and resources

Competitive advantage derives from deeply rooted capabilities (Prahalad and Hamel, 1990). There are three basic capabilities. Innovation capability is the ability to develop new products and process and achieve superior technology. Production and service capability is the ability to produce and deliver differentiated products and service to the customer regarding quality, flexibility, time, and cost. Market management capability is the ability to market and sell products and services efficiently and effectively (Rangone, 1999). An organization needs to hold appropriate complementary resources and manage them effectively to obtain and enhance these capabilities. Research based on the resource-based view regards a company’s resources as the source of competitive advantage (Teece et al., 1997). Resources may be both tangible and intangible, with the latter often described as IC in the management literature. IC includes human capital, structural capital, and relational capital (Swart, 2006). To be identified as the source of competitive advantage, IC items should have the following characteristics: (1) valuable to differentiate the company to its competitors (in extreme cases, to prevent competitors entering the market); (2) rare compared to the competition; (3) inimitable, that is, difficult for competitors to imitate or imitable but at a high cost, which causes inefficiency; (4) unsubstitutable by other resources (Barney, 1991; Collis and Montgomery, 1995; Rangone, 1999).

p.239

Strategy: competitive strategy and KM strategy

Strategy is the key concept in competitive advantage. IC management and KM must be integrated at an early stage to monitor progress and “keep the body of knowledge alive and vibrant to secure the enterprise’s well-being and long-term viability” (Wiig, 1997, p. 405). To understand how IC is strategically managed to obtain a competitive edge, it is significant to look at two different strategies: competitive strategy and KM strategy.

The concept of competitive strategy has been the subject of extensive research since the 1960s. In the past 50 years, it has been extended, examined, and redefined in many ways. There are two contrasting theories of strategy: prescriptive and descriptive theory. The prescriptive theory defines strategy as the process of determining the organization’s long-term goals and objectives, of adopting a course of action, and allocating sufficient resources (Chandler, 1962). Alternatively, it is defined as a fundamental pattern of present and planned objectives, resource deployments, and interactions of an organization with markets, competitors, and other environmental forces (Kerin et al., 1990). In the SME literature, the definition of strategy includes five components. They are “planned activities being carried out to achieve stated objectives, resources and capabilities being deployed to a strategic decision, markets being entered, explored and learned from, competitors being engaged and benchmarked, and environments providing signals filtered through personal and entrepreneurial networks” (Burke and Jarratt, 2004, p. 129). In contrast, descriptive theory, based on practice, shows that strategy does not need to be deliberately planned, react to the external environment, or benchmark competitors.

Mintzberg et al. (2008) summarized descriptive and prescriptive strategy theory, arguing that strategy should require a number of definitions, and five in particular: a strategy is a plan that means a direction, a guide, or course of action into the future; a strategy is a pattern that refers to the consistency in behaviour over time; a strategy is a position showing the location of particular products in particular markets; a strategy is a perspective that directs the fundamental way of doing things; moreover, a strategy is a ploy – a particular manoeuvre intended to outwit an opponent or competitor. While the first and the second are two different processes of strategic formulation, the third and fourth represent different strategic content.

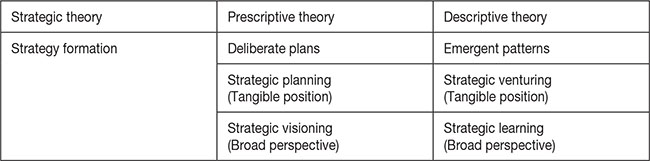

Figure 15.2, proposed by Mintzberg et al. (2008), combines plan and pattern with position and perspective to analyse strategy formation. According to Mintzberg et al. (2008), the definition of strategy as a plan represents a view that strategy is made for the future with previously determined objectives. Along with this line of definition, the strategy is intended and deliberately planned. In contrast, the definition of strategy as a pattern that evolves in the past implies that strategy emerges over time as intentions collide with and accommodate a changing reality. Strategy formed in this way is called emergent strategy, and is formulated in the learning process.

p.240

Figure 15.2 Types of strategy theory and strategy formulation

Source: Adapted from Mintzberg, 2008, p. 16

Compared with competitive strategy, KM strategy has a more focused content. The KM literature focuses on the identification, acquisition, sharing, conversion, and utilization of knowledge. KM strategy includes the following dimensions (Hansen et al., 1999; Choi and Lee, 2002; Bierly and Daly, 2007; Greiner et al., 2007; Choi et al., 2008):

1 KM objective. KM may aim to improve efficiency or improve innovation.

2 Knowledge source. KM strategy can be classified as internal or external oriented depending on the source of knowledge.

3 Knowledge sharing and transfer. KM strategy can be divided into codification and personalization with the former focusing on the reuse of knowledge so that knowledge is usually codified by application of technology, while the latter features face to face communication where knowledge is tacit.

Research method

Some researchers criticized the top-down approach to guiding IC reporting, calling for more research on what works (and does not) in specific organizational contexts from a bottom-up perspective (Mouritsen, 2006; Dumay, 2012). In this study, we selected five companies from a large sample to analyse the contribution of their IC management to competitive advantage from 2005 to 2016. First, 3,000 enterprises, revenues of which increased over the period 2005 to 2007 were selected from 78,000 SMEs. Those with fewer than ten employees were then excluded. A survey was conducted via a questionnaire sent to the selected sample companies to explore the following three questions.

1 What kind of IC do you consider a source of competitive advantage?

2 How do IC elements interact to create corporate value?

3 How do companies manage and assess intellectual assets?

p.241

Table 15.1 Profiles of the case companies

Based on the questionnaires received, we approached 21 companies with active IC management or specific KM. Among them, eight companies accepted our interview request. The first interviews were undertaken in 2008.1 We followed these up regularly and additional interviews were conducted in 2016. Information about these companies was collected from various sources including interviews, the company webpage, word of mouth, and databases. Three companies were excluded because of inaccessibility, leaving a sample of five companies (see Table 15.1).

All the case companies had high growth in sales and profit from 2005 to 2007. Company A is a ‘development-based’ engineering company with image processing technologies as its core technology. Despite the effects of the global financial crisis, it had high growth until 2015, with its capital tripling and number of employees doubling.

Company B was founded in 1992 by its current three executives, formerly technicians at a synthetic leather manufacturer. The successful development of new technologies based on plastic film sheet moulding pushed rapid growth from 2005 to 2007, with sales growth of 191 per cent, and an earnings growth rate of 145 per cent. Although this rate of growth could not be maintained in later years, the company’s growth was continuous with the number of employees increasing from 18 in 2007 to 30 in 2016.

Company C specializes in the processing of glass products for semiconductors. It is a wholly-owned subsidiary of a major semiconductor and printing manufacturer. In the fiscal year 2005, the company emerged as the global leader in quartz glass tanks. However, after 2008, the company’s growth stalled and sales, profits, and total assets decreased from 2010 to 2015, with a small recovery in 2016. It has 85 employees as at 2016, a 25 per cent decrease from 2008.

Company D is a wholesaler of raw materials for steel established in 1909 as a privately-owned enterprise. The growth rates of net profits from 2005 to 2007 were 169 per cent, 181 per cent, and 131 per cent respectively. The company has continued to show steady growth in profit in recent years.

Company E was founded in 1999. It is involved in the planning, development, and wholesale of limited area character-related goods for popular tourist destinations. The company grew rapidly from 2005 to 2008 with sales increasing tenfold due to the successful development and marketing of a popular character product. It aimed to list on the Tokyo Stock Exchange in 2009, but since 2008 the company has been contracting and in 2016, was one-third of its peak size.

p.242

Findings of the case analysis

Snapshot of competitive advantage and intellectual capital 2008

The case companies were divided into three groups based on their specific capabilities: (1) technology-based production capability; (2) information capability; and (3) marketing capability. Table 15.2 summarizes what the case companies indicated were the drivers of competitive advantage and the strategy they adopted to obtain advantage in position and performance.

Type 1: Technology-based production capability

The first group of companies shares similarities in that they are in a niche market with specific demands for products, they are in competition with very large companies in this market, and they were founded based on the experience and know-how of the founders and staff in the same industry. The three companies each adopted different strategies to survive and win in such a market.

Table 15.2 Competitive advantage and IC management of case companies as of 2008

p.243

Company A differentiates itself from rivals by providing high value-added products at a higher price than those of its rivals. Its innovative product is developed based on an idea of the CEO, and its high-end product strategy was formulated when the company was established. However, this strategy could not be successfully implemented without the efforts of the key world-class technicians who have five years or more practical experience in image processing, and with accumulated knowledge and experience in image processing algorithms, optical technologies, and electricity and machinery in the same industry, and who jointly established the company. A stock option system was introduced to motivate technicians and developers. Company A’s success stems from its win-win relationship with its rival, the top company in the market. By entering a licence agreement with this company, which has a library of application tools, Company A can make the best use of the rival company’s technology and convert it to its advantage.

In contrast to Company A, Company B has no specific idea or objective for product development. Instead, its specific product and unique film sheet processing technology were developed as a result of customers’ specific requests. This customer-oriented development strategy is a typical emergent strategy.

If a customer says they want to do something, then we try, without any special consideration of the cost. You could say we enjoy this. We try plenty of things, one of which will tie into some interesting technological development.

(CEO of Company B)

The standard processing techniques only allow for high performance film sheets to be produced at a thickness of 0.4mm and are traditionally used in stationery manufacturing and packaging manufacturing. However, the company was able to produce an ultra-thin, highly transparent film sheet that is one-tenth the thickness of 0.04mm. This processing technology was revolutionary and is used in new areas like LCDs and plasma screen displays. To protect its technology, Company B has applied for a patent. In the interview, the company executives summarized the critical resources contributing to Company B’s success as key technicians, unique technology, and intellectual property, as well as the close relationship with customers and business partners.

Company C’s differentiation lies in its high-quality product guaranteed by the craftsmanship of skilled workers, quality management system, and division of labour. The company has earned a worldwide reputation in quartz glass processing technology, driven by the presence of skilled workers at the company who contributed to its founding and who are regarded as critical IC. On-the-job training helps apprentices to learn the craftsmanship required, which takes seven to ten years to master, hence the technology is difficult to imitate. The subsequent development of the company has been based not only on the craftsmanship of these individual workers but also on the company’s efforts to significantly improve efficiency, reducing errors and costs by transitioning its production system to a system of division of labour and adopting ISO.

Type 2: Information capability

Company D has positioned itself as an ‘information trading company’ despite its core business being distributing and wholesaling steel raw material. This creates customer value through swift action based on its high power of information acquisition. The competitive advantage that Company D has derived from this strategy is its ability to respond rapidly to customers’ demands and requests. While large companies seek huge-volume transactions with a small number of business partners with the aim of efficient management, Company D carries out small-volume decentralized transactions with many trading partners. At a glance, this appears to be an inefficient approach that increases costs. However, Company D is seeking “inefficient efficiency” rather than short-term profit, underpinned by long-term relationships of trust, consistent with traditional Japanese business practices. This has boosted Company D’s ability to gather information, increasing the efficiency of business, thereby enabling economy of speed. The IC that contributes to Company D’s growth includes its unique management philosophy, strong leadership by the CEO, organization culture and structure, processes that support rapid information gathering and matching, and long-term relationships with various business partners.

p.244

Type 3: Marketing capability

Company E’s dramatic growth in financial performance from 2005 to 2008 was achieved by successfully planning and selling character goods designed especially for the region’s souvenir market. The character is unique and popular among both men and women, old and young. The character-themed goods are designed with their styles showing regional characteristics and sold to retailers specializing in tourist merchandise. After a successful trial in Okinawa, this marketing model was copied and successfully applied to other regions. The CEO summarized the IC that supported the company’s competitive advantage as the exceptional ability of management coupled with the experience and capabilities of the person in charge of planning, the prioritization of relationships with regional retailers, the close cooperative supply system, and the small scale of production, which reduces problems associated with base-stock inventory.

Sustained superiority, strategy and IC management: winners versus losers

The prior literature has provided few case studies considering whether and how IC contributes to high performance (for example, Marzo and Scarpino, 2016), in particular, empirical studies that demonstrate whether and how IC can help sustain competitive advantage over time. Hence we followed up the companies in 2016 to see if their performance had been sustained over time. Not all the companies in our sample had sustained high performance and we have separated the companies on the basis of winners – those that sustained competitive advantage – and losers – those that did not. We re-examined the IC elements regarded as critical success factors to see whether they remained relevant, and analysed and compared the companies’ competitive strategy and KM strategy to explore the factors that lead to sustained organizational success (Table 15.3).

Winner group

p.245

Table 15.3 Competitive strategy and KM strategy

Common to the winner group companies is that the IC items identified in 2008 as the source of competitive advantage still work well. We found that winner companies successfully combined competitive strategy with KM strategy; this may have been intended or unintended. For example, the competitive advantage of both Company A and Company B is their innovative technology. To maintain their position, Company A focused on one type of product and continuously renewed the technology to make the product easier to use while maintaining precision and versatility. In contrast, Company B had no deliberate plan but continued its customer demand-based development strategy, which also helped the company to grow.

On the other hand, these companies’ KM strategy is more open, actively utilizing external expertise, experience, and knowledge, which helps to overcome the inherent shortages in resources. To continuously develop the high value-added product, Company A collaborates with large companies to utilize their technology and convert them into a new product. Like Company A, Company D attached great importance to external intelligence. The significance of the network was emphasized by the CEO and openly disclosed on the company’s webpage. A network club was created to provide a ‘ba’ – a shared context in which knowledge is shared, created, and utilized so that people from outside the company can share experience, and ideas and business opportunities can be jointly explored. In knowledge creation, generation and regeneration of ba are key, as ba provides the energy, quality, and place to perform individual conversions and to move along the knowledge spiral (Nonaka et al., 2000). By doing so, Company D established a strategy combining internal- and external-oriented KM. In contrast, Company B has a more internal-oriented KM strategy, in which development was conducted based on the explicit or implicit needs of customers, but was realized based on the expertise and know-how of technicians. This may be why Company B, though considered successful, only grew slowly.

Company D’s competitive advantage was maintained over the long term because it relies on management philosophy, work processes, and organizational structure, characteristics considered as KM infrastructure for knowledge management and impossible for other companies to copy. Company D’s philosophy is that instead of benchmarking competitors to formulate strategy, it focuses on its own corporate value, what kind of company it wants to be, and how to do business in the long term. Its work processes encourage information exchange between employees so that new business opportunities can be taken, and problems identified and solved in a timely fashion. Employees write a daily report, which is then summarized and disclosed so that silos between different districts are broken down and knowledge acquired, accumulated, and utilized company-wide. The organization’s structure is also designed to be very flat to allow information sharing and business opportunity identification.

p.246

Loser group

The loser group shares similar characteristics in that the IC items identified by their managers as value drivers have lost value in the later years. For example, Company C did not lose its technology advantage in the current market. While it is still the world leader in quartz processing, with a high level of efficiency achieved through mass production and good customer relations, its focus on efficiency meant that it did not respond to changing markets, and relied too heavily on orders from the parent company, which is facing a contracting market, especially after the financial crisis. Meanwhile, Company C’s KM appears to be very internal-oriented, lacking channels to external knowledge resources. While it has been exploring new markets where its technologies can be employed, it needs to integrate its current knowledge with new knowledge from the different industries in order to realize new opportunities.

Similarly, Company E has downsized as its performance has decreased while its IC remains static. The company’s success was based on one excellent idea and no hot commodity can have longevity without value being constantly added. Company E did not use any value-added activities to strengthen the brand of the character goods it designed and its business model could not prevent other companies from entering the market and copying their methods. More importantly, Company E had no strategy to improve the capability of planning and design. The employee who was regarded as the source of competitive advantage in this instance becomes a disadvantage to the company.

Discussion

What kinds of IC deliver sustained competitive advantage for SMEs?

In the IC literature, dozens of IC components have been proposed as the source of competitive advantage. For example, Gallego and Rodrıguez (2005) investigated 39 Spanish companies using a questionnaire to analyse 25 items of IC. They found that IC such as customer relationships, employee experience, information technologies, brand image, procedures, and systems are most relevant, and the number of indicators used by companies is about 20. Steenkamp and Kashyap (2010) surveyed 30 New Zealand SMEs using 23 items of IC components. They had similar results, finding that most of the IC items are important, including customer satisfaction, customer loyalty, corporate reputation, product reputation, and employee know-how. However, as revealed by our study, some of these will not necessarily lead to future success.

Barney (1991) identified resources that are valuable, rare, inimitable, and unsubsitutable as key to competitive advantage. However, can these kinds of resources deliver sustainable competitive advantage that persists despite variable economic and market conditions? To answer the question, Peteraf (1993) offered the following requirements as necessary for transforming resources with the above characteristic into sustainable competitive advantage: resource heterogeneity, which means resource bundles vary from firm to firm; ex ante limits to competition-barriers that deter or prevent other firms from attempting to develop the same resource bundle; ex post limits to competition – barriers that make it difficult for competitors to imitate what the pioneer is doing effectively; and resource immobility. When it comes to SMEs, in the long run, the most important measure is to prevent imitation to defend existing advantage or renew resources advantage through innovation.

p.247

From our analysis, inimitability not only means it is impossible to imitate a resource technically but also legally, efficiently, and culturally. For SMEs, legal protection of patents and trademarks is one of the most effective ways to protect themselves from larger rivals. For example, Company B learned the importance of patents from a painful lesson in the past in which a larger company copied its technology. Organizations can also prevent imitation by focusing on a specific area through which they obtain the technology advantage that makes imitation more costly, as did Company A. While large enterprises have the capacity to develop the same technology, buying the product may be more cost efficient. Organizational culture is also a barrier to imitation, as can be seen in the case of Company D. Its CEO is not concerned that employees will give away the secret of their success because “it is hard to describe, even if they can describe they cannot copy it”. The employee who leaves cannot help a competitor replicate what is unique about the organization.

How does KM facilitate sustained competitive advantage?

Preventing imitation may work in an existing market; however, maintaining the resource-based advantage can be achieved through renewing resources and capabilities through KM. However, this can only be achieved when some conditions are met. First, as some researchers indicate, an organization managing knowledge well has the potential to obtain competitive advantage and create significant value, but only if it is linked to its overall strategy and strategic decisions (Egbu et al., 2005; Lai and Lin, 2012; Lee et al., 2013). Company A is an example of this. Second, KM with an objective of innovation rather than efficiency is essential, especially in a changing market. For example, Company B, despite having the most advanced technology, lost its advantage because it focused on quality and efficiency instead of development of revolutionary technology or innovative ways to use the technology when facing a shrinking market. Third, instead of relying on the knowledge inside the organization, the utilization of external technologies and expertise is critical because SMEs often have a bottleneck of resources. Company D overcame this because it did not see employees as success factors and therefore higher turnover did not lead to a competitive disadvantage. Company D worked in a holistic way to act as a knowledge creation facilitator.

The findings of our study are consistent with previous studies (for example, Wong and Aspinwall, 2005) which find that KM is conducted in an informal way in SMEs without the use of the language and concepts of KM, specific staff, and formal KM structures. Regardless of whether KM is informally or formally conducted, if properly integrated with overall strategy, with a more open source and directed towards creation of new capabilities, it should ultimately lead to long-term competitive advantage.

How to incorporate strategization into IC management

Mintzberg et al. (2008) summarized ten schools of strategy theories in their popular book Strategy Safari. Strategic IC management cannot be described using a simplified model considering the existence of a variety of strategy theories and practices; however, IC theory is easier to incorporate into some schools of strategy than others. The idea of IC combines the resource-based theory and dynamic capabilities approach. The former implies that the capabilities of the firm are rooted in the evolution process of the organization while the latter regards them as developed through strategic learning. These two views, though different, are related with their focus on sustaining and developing internal capabilities, that is, the inside-out view, rather than the outside-in view (Mintzberg et al., 2008). Therefore, resource-based theory is often criticized because it is difficult to incorporate into the position school of strategy, while fitting well with the culture school of strategy.

p.248

Moreover, prescriptive strategy theory cannot explain practice entirely. Ricceri (2008) called for the incorporation of strategization within the management of IC. Both proper strategy formulation and execution are needed to link IC to performance. This separation of formulation and implementation is central to the design school of strategy and convenient for a business school case study. However, in practice, strategy formation is a long, subtle, and difficult process of learning. If managers:

[d]etach thinking from acting, remain in their headquarters instead of getting into factories and meeting customers where the real information may have to be dug out, then it may be a cause of some of the serious problems faced by some of the today’s organizations.

(Mintzberg et al., 2008, p. 41)

Third, strategy at its essence is integrative. Though some schools of strategy are more popular than others, all of them are just a part of a big `animal’. The problem with the resource-based is that it explains too easily what already exists, rather than tackling the tougher question of what can come into being – just as our study found that some IC developed as a past strategy will not necessarily lead to future success. A combination of other perspectives to form a holistic view of strategic IC management may help to predict the future. Our study reveals that those in the winner group like Company A and Company D adopted an integrated rather than specific approach to formulating strategy. The integrated approach strengthens the causal link between IC, positions, and final company performance. This holistic view of strategic IC management is consistent with the way information users evaluated IC. For example, in 2008, a committee organized by the Organization for Small & Medium Enterprises and Regional Innovation in Japan investigated perceptions of IC reporting among 439 Japanese banks (Yosano and Koga, 2008). The result shows that the lenders have difficulties in judging internal resources, as well as corporate strategy, as isolated information. Rather, they use integrated information that is tightly correlated with both internal resources and strategy, and incorporate other data regarding the company’s relationship with other businesses and society.

Does the Japanese style of IC management exist in SMEs?

Uchida and Roos (2008) compared large companies using the western style of intellectual resources management and the Japanese style. The former was labelled as strategy rationality style, while the latter was described as resource rationality style. The western IC management with strategic rationality relied on external environment analysis and utilized intellectual resources according to strategic goals, featuring deliberate strategy and an indirect management of intellectual assets. In contrast, the Japanese style of IC management or resource rationality based its activities on the company’s internal resources. Resource rationality is formulated in the process of utilizing IC and is a direct management of intellectual assets (Yao and Bjurström, 2014). Therefore, sometimes Japanese companies are criticized for their lack of strategic views from the western perspective of strategy (deliberate strategy), which is based more on the analysis of external competition and environment. The strategic formulation of Japanese companies is more internally oriented and resource-based (emergent strategy). Our study is consistent with this, finding that of the five companies, four showed an emergent pattern of strategy formation and attached great importance to learning from the process.

p.249

The other characteristic of Japanese SMEs is that IC management is conducted based on a broad perspective instead of position analysis. Instead of relative value, some of the Japanese companies have a propensity for pursuing absolute value, which is regarded as the essence of innovation (Nonaka and Katsumi, 2004). These kinds of Japanese companies try to differentiate themselves from others with unique intellectual resources that only exist within themselves. This perspective-based strategy formulation can be seen in all five case companies.

Conclusion

IC is more important as a source of competitive advantage in SMEs than large companies because SMEs have fewer tangible resources, and should compete through IC (Jardon and Martos, 2012, p. 463). However, the lack of understanding of IC management in SMEs and the application of prescription strategy theory to explain the link between IC and firm performance has caused practice difficulties, with investors and creditors finding it difficult to evaluate IC and use it to predict future performance, and managers losing interest in IC reporting. In this situation, the so-called third stage of IC research that examines what works in practice is needed. This chapter attempts to explore how IC contributes to sustained competitive advantage through strategic management in Japanese SMEs.

Our research reveals that not all IC can deliver competitive advantage in the long run. SMEs’ technology and business know-how can be copied by rivals, especially large companies. The winner group in our study focus on technology, legal protection, efficiency, and culture to sustain a competitive advantage. Only by combining with overall competitive strategy could KM facilitate long-term competitive advantage. High performance companies tend to adopt a KM strategy that aims at innovation instead of efficiency, and more positively utilize the external resources of capability, expertise, know-how, and technology. There are different ways to incorporate strategy into IC management and, when compared to the loser group, the winners adopted a more integrated approach to formulating strategy. The Japanese style of IC management is more internally oriented with the strategy formulation process featuring an emergent pattern rather than a deliberate plan.

Our research has practice and policy implications. As the case companies we chose for analysis were all high growth companies in the first three years, understanding the reason for the difference in performance in the later years may help managers to take measures to prevent imitation and mobility of their capability and resources, and to review and modify their KM and strategy formation so that competitive advantage can be sustained for a longer period. Meanwhile, our results will also help investors and others who need to evaluate IC management to predict the future performance of SMEs. Furthermore, the government may provide more support for SMEs to develop, protect, and improve IC by taking into account the features of the Japanese style of management.

Instead of applying one strategy definition and theory, we analyse strategy formation based on Mintzberg et al.’s (2008) idea that strategy may include many definitions and approaches, all of which together provide a whole picture of a big animal. We revealed that strategic IC management in practice takes various forms that leads to different performance in the long term. This implies that the strategy theory researchers choose to study in relation to IC management should be carefully examined to avoid fragmentation and prejudice. To uncover the secret inside the black box, more sophisticated research design and bold exploration are needed.

p.250

Note

1 We appreciate the Small and Medium Enterprise Agency for assisting us in the case study, which is a part of the OECD high-growth project 2008. We are also thankful to T. Yosano of Kobe University for assisting in the interviews.

References

Aragón-Sánchez, A. and Sánchez-Marín, G. (2005), “Strategic orientation, management characteristics, and performance: A study of Spanish SMEs”, Journal of Small Business Management, Vol. 43, No. 3, pp. 287–308.

Barney, J. (1991), “Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage”, Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 99–120.

Bierly, P. E. and Daly, P. S. (2007), “Knowledge strategies, competitive environment and organizational performance in small manufacturing firms”, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, Vol. 31, No. 4, pp. 493–516.

Burke, G. I. and Jarratt, D. G. (2004), “The influence of information and advice on competitive strategy”, Qualitative Market Research, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 126–138.

Chandler, A. (1962), Strategy and Structure: Chapters in the History of American Enterprise, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Choi, B. and Lee, H. (2002), “Knowledge management strategy and its link to knowledge creation process”, Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 23, pp. 173–187.

Choi, B., Poon, S. K., and Davis, J. G. (2008), “Effects of knowledge management strategy on organizational performance: A complementarity theory-based approach”, Omega, Vol. 36, pp. 235–251.

Cohen, S., Naoum, V. C., and Vlismas, O. (2014), “Intellectual capital, strategy and financial crisis from a SMEs perspective”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 294–315.

Collis, D. J., and Montgomery, C. (1995), “Competing on resources: Strategies in the 1990s”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 73, pp. 119–128.

Coyne, K. P. (1986), “Sustainable competitive advantage: What it is, what it isn’t”, Business Horizons, Vol. 29, No. 1, pp. 54–61.

Day, G. S. and Wensley, R. (1988), “Assessing advantage: A framework for diagnosing competitive superiority”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 1–20.

Demartini, P. and Del Baldo, M. (2015). “Knowledge and social capital: Drivers for sustainable local growth”, Chinese Business Review, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 106–117.

Dumay, J. (2012), “Grand theories as barriers to using IC concepts”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 13, No. 10, pp. 4–15.

Dumay, J. and Garanina, T. (2013), “Intellectual capital research: A critical examination of the third stage”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 10–25.

Dumay, J. and Guthrie, J. (2012), “IC and strategy as practice”, International Journal of Knowledge and Systems Science, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 28–37.

Egbu, C. O., Hari, S., and Renukappa, S. H. (2005), “Knowledge management for sustainable competitiveness in small and medium surveying practices”, Structural Survey, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 7–21.

Gallego, I. and Rodrıguez, L. (2005), “The situation of intangible assets in Spanish firms: An empirical analysis”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 105–126.

Greiner, M. E., Bo’hmann, T., and Krcmar, H. (2007), “A strategy for knowledge management”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 11, No. 6, pp. 3–15.

Guthrie, J., Ricceri, F., and Dumay, J. (2012), “Reflections and projections: A decade of intellectual capital accounting research”, The British Accounting Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 68–92.

Hansen, M., Nohria, N., and Tierney, T. (1999), “What’s your strategy for managing knowledge?” Harvard Business Review, Vol. 77, No. 2, pp. 106–116.

Hutchinson, V. and Quintas, P. (2008), “Do SMEs do knowledge management? Or simply manage what they know?” International Small Business Journal, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 131–154.

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) (2013), The International <IR> Framework, International Integrated Reporting Council, London.

Itami H. (1987), Mobilizing Invisible Assets, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Jardon, C. M., and Martos, M. S. (2012), “Intellectual capital as competitive advantage in emerging clusters in Latin America”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 462–481.

p.251

Kerin, R. A., Mahajan, V., and Varadarajan, P. R. (1990), Contemporary Perspectives on Strategic Market Planning, Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA.

Lai, Y. L. and Lin, F. J. (2012), “The effects of knowledge management and technology innovation on new product development performance an empirical study of Taiwanese machine tools industry”, Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences, Vol. 40, pp. 157–164.

Lee, V. H., Foo, A. T. L., Leong, L. Y., and Ooi, K. B. (2016), “Can competitive advantage be achieved through knowledge management? A case study on SMEs”, Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 65, pp. 136–151.

Lee, V. H., Leong, L. Y., Hew, T. S., and Ooi, K. B. (2013), “Knowledge management: A key determinant in advancing technological innovation?” Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 17, No. 6, pp. 848–872.

Marzo, G. and Scarpino, E. (2016), “Exploring intellectual capital management in SMEs: An in-depth Italian case study”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 27–51.

Mintzberg, H., Ahlstrand, B., and Lampel, J. B. (2008), Strategy Safari: The Complete Guide Through the Wilds of Strategic Management, Pearson Education, Toronto, ON.

Mouritsen, J. (2006), “Problematising intellectual capital research: Ostensive versus performative IC”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 820–840.

Nonaka, I. and Katsumi, A. (2004), The Essence of Innovation (in Japanese), Nikkei BP.

Nonaka, I. and Takeuchi, H. (1995), The Knowledge-Creating Company: How Japanese Companies Create the Dynamics of Innovation, Oxford University Press, New York.

Nonaka, I., Toyama, R., and Konno, N. (2000), “SECI, ba and leadership: A unified model of dynamic knowledge creation”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 5–34.

Peteraf, M. A. (1993), “The cornerstones of competitive advantage: A resource-based view”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 79–191.

Porter, M. E. (1985), Competitive Advantage, The Free Press, New York.

Prahalad, C. K. and Hamel, G. (1990), ‘The core competence of the corporation”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 68, No. 3, pp. 79–91.

Rangone, A. (1999), “A resource-based approach to strategy analysis in small-medium sized enterprises”, Small Business Economics, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 233–248.

Ricceri, F. (2008), Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Management: Strategic Management of Knowledge Resources. Routledge Advances in Management and Business Studies: Routledge, London.

Steenkamp, N. and Kashyap, V. (2010), “Importance and contribution of intangible assets: SME managers’ perceptions”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 368–390.

St-Pierre, J. and Audet, J. (2011), “Intangible assets and performance: Analysis of manufacturing SMEs”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 202–223.

Sullivan, P. H. (2000), Value-driven Intellectual Capital: How to Convert Intangible Corporate Assets into Market Value, John Wiley & Sons Inc., New York.

Swart, J. (2006), “Intellectual capital: Disentangling an enigmatic concept”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 136–159.

Takahashi, T. (2012), Strategy for the Age of Knowledge-Organization, Diamond Books, India.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., and Shuen, A. (1997). “Dynamic capabilities and strategic management”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18, No. 7, pp. 509–533.

Uchida, Y. and Roos, G. (2008), Intellectual Capital Management for Japanese Firms (in Japanese). Chuokeizai-sha, Inc.

Wiig, M. K. (1997), “Integrating intellectual capital and knowledge management”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 399–405.

Wong, K. Y. and Aspinwall, E. (2005), “An empirical study of the important factors for knowledge management adoption in the SME sector”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 64–82.

Yao, J. and Bjurström, E. (2014), “Trends and challenges of future IC reporting experiences from Japan”, in P. Ordoñes de Pablo and L. Edvinsson (Eds), Intellectual Capital in Organizations, Non-Financial Reports and Accounts, Routledge, New York, pp. 277–296.

Yosano, T. and Koga, C. (2008), “Influence of intellectual capital information on credit risk rating process criterion and credit conditions: Survey analysis of Japanese financial institutions”, Proceedings of 4th Workshop on Visualizing, Measuring and Managing Intangibles and Intellectual Capital, 22–24 October.