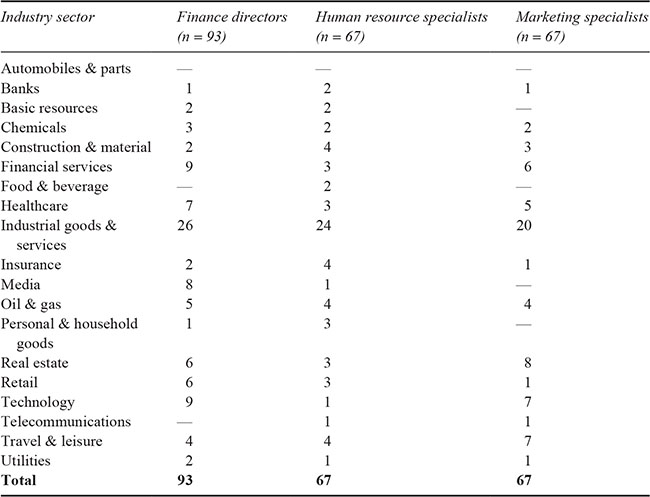

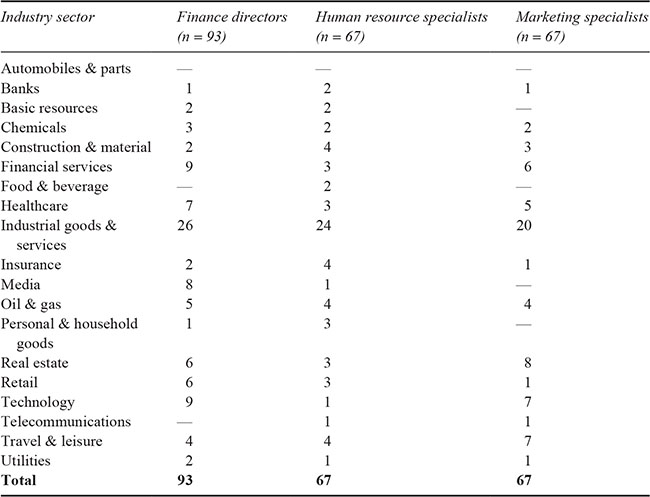

Table 18.1 Industry classification for the companies of the key functional specialists providing questionnaire survey evidence

Note: n = 67 because one marketing questionnaire was returned anonymously

p.284

INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL DISCLOSURE

What benefits, what costs, is it voluntary?

Sarah Jane Smith

Introduction

This chapter addresses the disclosure of intellectual capital (IC). It is possible to identify the three stages in the development of IC research in terms of IC disclosure. During the first stage, specific disclosures came to be identified as IC disclosures, thus raising awareness. During the second stage, generic disclosure theories were applied in the IC context. The third stage investigates the disclosure of IC in practice. Within the literature, IC disclosure has been examined from a range of philosophical perspectives: positivist, interpretivist, and critical.

IC refers to intangible resources that create corporate value (Ashton, 2005). IC is embedded within a spectrum of corporate activities, and has been generally categorized into human, structural, and relational capital (Meritum, 2002). Human capital encapsulates the knowledge, skills, experiences, and abilities of people. Structural capital includes the value embedded in organizational routines, procedures, systems, cultures, and databases. Elements of structural capital may be legally protected and become intellectual property rights, legally owned by the company under separate title. Relational capital refers to all resources linked to the external relationships of the firm, such as relationships with investors, creditors, customers, and suppliers. Relational capital also comprises the perceptions that stakeholders hold about the company. Numerous components or elements have been associated with these three categories of human, structural, and relational capital.1

Under contemporary international financial reporting regulations, many IC elements are not recognized in the financial statements, and are historically not subject to extensive mandatory narrative reporting requirements. However, the narrative reporting context is constantly changing and, beyond the regulatory environment, the opportunity to voluntarily disclose IC does exist within the narrative sections of the corporate annual report and other channels of corporate communication.

A variety of incentives are suggested in relation to the disclosure of IC information that is not captured by the traditional financial reporting framework. The incentives to voluntarily disclose information, in general, can be explained in terms of a variety of economic and managerial theories, each of which focuses on a different aspect of corporate behaviour. Establishing trustworthiness with stakeholders and providing a valuable marketing tool (Van Der Meer-Kooistra and Zijlstra, 2001) are prime concerns.

p.285

Capital market incentives, such as the opportunity to increase transparency to capital markets, reduce information risk, lead to strong benefits in the form of a lower cost of capital, increased share price, and increased liquidity (Richardson and Welker, 2001; Verrecchia, 2001; Lundholm and Van Winkle, 2006). The more social exposure a company receives, the more it needs to legitimize its existence (Patten, 1991). Through information disclosure, external perceptions of legitimacy can be altered and the costs arising from non-legitimacy avoided (Deegan, 2000). Additional economic costs in the form of loss of competitive advantage, litigation exposure, and the direct costs of collecting, processing, and disseminating information, act as disincentives (Elliott and Jacobson, 1994). The competitive disadvantage to disclosure is particularly pertinent in the IC context given that IC is a prime source of competitive edge in a global market place (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Lev, 2004). Value creation processes are potentially highly sensitive, and thus disclosing such information would be a serious burden. Importantly, therefore, the management of IC and the disclosure of IC are mutually dependent activities in the value creation process with disclosure in itself having the potential to create or destroy value (Beattie et al., 2013). In theory, voluntary disclosure of IC information will occur if the benefits exceed the costs (Heitzman, et al., 2010). However, due to bounded rationality, not all potential benefits and costs might be taken into consideration by corporations.

The purpose of this chapter is to explore the benefits, costs, restrictions, and alternative perspectives to IC disclosure. This is achieved through a synthesis of the evidence obtained from a direct survey investigation of, and follow up interviews with, UK listed companies (228 questionnaire responses and 17 interviews) across finance, marketing, and human resource specialists.2 This chapter contributes an analysis of this evidence with additional interpretative commentary, particularly in relation to recent developments in the narrative reporting arena, providing a platform from which the IC disclosure decision may be deliberated.

IC disclosure prior research

Prior studies have extensively investigated the extent and nature of IC disclosure in corporate annual reports. The majority of such studies use content analysis to capture indirectly the extent to which different IC components are disclosed to infer their relative importance. Prior studies have focused either on a single country setting (for example, Guthrie and Petty, 2000; Brennan, 2001; April et al., 2003; Bontis, 2003; Bozzolan et al., 2003; Goh and Lin, 2004; Abdolmohammadi, 2005; Abeysekera and Guthrie, 2005; Unerman, et al., 2007; Li et al., 2008; Campbell and Rahman, 2010) or across countries (for example, Vandemaele et al., 2005; Vergauwen and Van Alem, 2005; Bozzolan, et al., 2006; Guthrie et al., 2007). Findings suggest that relational capital is generally the most extensively reported IC category (Abeysekera, 2006). In their pioneering study, Guthrie and Petty (2000) investigated IC disclosure in the annual reports of 20 Australian companies. They found 40 per cent and 30 per cent of IC disclosures relate to relational capital and human capital respectively, although overall disclosure was evaluated as ‘low’. Employing the same framework, similar studies were conducted in Ireland (Brennan, 2001) and Italy (Bozzolan et al., 2003). Bozzolan et al. (2003) found relational capital to comprise just under half of IC disclosures, with particular attention given to customers, distribution channels, business collaboration, and brands. Human capital made up a smaller proportion, 21 per cent, of total disclosure. Guthrie and Petty (2000) related the low IC disclosure levels found to the lack of reporting frameworks and the lack of initiative in measuring and externally reporting. The potential loss of competitive advantage to disclosure has also been suggested as an explanation (Bozzolan et al., 2003).

p.286

Subsequent studies have developed and extended the range of components of IC investigated, for example Abeysekera and Guthrie (2005). UK studies of this type are relatively few. Unerman et al. (2007) and Striukova et al. (2008) use content analysis to investigate IC disclosure across a range of corporate media for 15 UK companies operating in four different industry sectors. Relational capital was found to account for 61 per cent of such disclosures with information relating to customers making up 20 per cent of total disclosure and being disclosed by all companies. Human capital accounted for 22 per cent, including information on work-related knowledge and employee information. For a sample of 100 UK listed companies, Li et al. (2008) found, based on word count, relational capital to account for 38 per cent and human capital 28 per cent of total IC disclosures. The most frequently disclosed components were found to be customers, relationships with suppliers and stakeholders, market presence, customer relationships, and market leadership, with over 90 per cent of sampled firms having disclosures of such items. The significance of relational capital was further emphasized in a longitudinal study by Campbell and Rahman (2010), who reviewed the annual reports of the major UK retailer Marks and Spencer over the period 1978 to 2008. The proportion of relational capital was found to vary between 45 per cent and 70 per cent of total IC disclosure, making it the most disclosed category of IC throughout the 31-year period. Since 2001, rapid growth in relational capital disclosure has been observed, with information on brands, distribution channels, customers, and corporate image building being the most frequently disclosed.

The importance and disclosure of IC has also been explored directly using case studies and semi-structured interviews on limited occasions (for example, Van Der Meer-Kooistra and Zijlstra, 2001; Chaminade and Roberts, 2003; Roslender and Fincham, 2004; Unerman et al., 2007). Roslender and Fincham (2004) conducted a series of interviews with senior managers in six UK knowledge-based companies. Whilst they note a growing importance attached to the long-term value creation aspirations of organizations, they find that understanding, measurement, and reporting of IC was generally under-developed. Further, external reporting was not considered, irrespective of any recognition of the contribution to sustained value creation. Unerman et al. (2007) conducted 15 in-depth interviews with UK finance directors. Despite some evidence to suggest a balance between informing capital markets and ensuring competitive advantage is not compromised, they concluded that the costs to external disclosure were not a significant obstacle. Abeysekera (2008) conducted 11 case study interviews when investigating human capital disclosure in the annual reports of firms in Sri Lanka, and concluded it is made to reduce tension between the firm and their stakeholders in the interest of further capital accumulation. The questionnaire survey method has seldom been used in the IC context. However, Gunther and Beyer (2003) obtained insights from 54 German listed companies where limited IC disclosure was associated with reluctance to damage competitive position. In summary, from prior research relational capital could be perceived as the most important IC category to value creation given the extent of observed disclosure. The IC disclosure decision-making process also appears to have the foundations for a cost-benefit trade-off, the benefits from putting value creation information into the hands of various stakeholders versus the cost of loss of competitive position.

Research methods: who provides the evidence for this chapter?

IC questionnaire survey evidence referred to in this chapter comes from 93 finance directors, 55 from companies listed on the London Stock Exchange main market and 38 from large companies listed on the Alternative Investment Market (AIM) market. The industry profile of these companies is shown in Table 18.1. The industrial goods and services industry is most represented. Whilst certain small industries, namely automobiles and parts, food and beverage, and telecommunications are not represented, overall industry profile is closely aligned with the population of domestic UK main market companies and the sample of AIM companies surveyed. The average annual sales and number of employees for these 93 companies was £561m and 3,108 respectively. Human and relational capital disclosure was further explored with 67 human resource specialists (87 per cent of whom indicated they held the positions of director or manager of human resources) and 68 marketing specialists (64 per cent of whom indicated they held positions of director, head or manager of marketing/business development). Both human resource and marketing specialists held their positions in main market companies. With the exception of automobiles and parts, all of the industry classifications are represented in the human resource specialists’ companies (Table 18.1). There are no marketing specialists from companies representing automobiles and parts, basic resources, food and beverage, media, and personal and household goods. Nevertheless, industry profiles are not significantly different from that of the population. Human resource specialists come from companies with average annual sales of £2,931m and average number of employees of 4,337. The marketing specialists come from companies with average annual sales of £1,552m and average number of employees of 7,561. Five interviews were conducted with finance directors from main market companies included in either the FTSE 100 or FTSE 250, and six interviews were with companies listed on the AIM market. Two interviews were conducted with human resource specialists and four interviews with marketing specialists, all from main market companies. All interviewees appeared hold senior relevant corporate positions.

p.287

Table 18.1 Industry classification for the companies of the key functional specialists providing questionnaire survey evidence

Note: n = 67 because one marketing questionnaire was returned anonymously

p.288

What elements of IC are most important to value creation?

The relative importance of the three categories of IC – human, relational, and structural capital, and their respective components – to value creation is considered in this section. The overall importance of IC to finance directors is emphasized by the finding that over 57 per cent of them believe IC contributes to 50 per cent or more of shareholder value. Human capital was ranked as providing the highest contribution of all three IC categories with no significant difference between structural and relational capital. Various components of these three categories were found to contribute to value creation to some extent. However, four components (customer relationships, employee skills and education, competitive edge in terms of quality of product/service, and company reputation) were considered the most valuable by a clear margin. According to the finance director of a FTSE 250 company in industrial goods and services: “The only assets we have in our business are our people . . . our main route to market is a combination of our people and their ability to convince clients” (Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 50). It is apparent though that the IC concept is not always considered in terms of the individual components that create value. A number of companies appeared to focus on how the components come together under a strategy for creating company value. This supports what Habersam and Piper (2003) term “connectivity capital”, a linking pin between human, structural, and relational capital. Mouritsen et al. (2001) highlight the importance of converting human capital into structural capital in the value creation process. This was evident from finance director responses: “All our products are based on years of research and developed knowledge and for practically everything we sell, we depend on patenting and protecting that knowledge” (Group Financial Reporter, FTSE 100 Healthcare company; Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 51). Irrespective, the human contribution to company value appears paramount, given that 75 per cent of finance directors viewed a low level of employee turnover as providing a moderate to very strong contribution “You can have all kind of intellectual property protections you want but basically the knowledge is in the people and therefore our ability to retain those people is really key” (Group Finance Director, FTSE 100 industrial goods and services company; Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 51).

Within the human capital category, employee skills and education were viewed as making the most important contribution by human resource specialists. This was followed by employee commitment, positive employee attitudes, positive employee behaviour, and employee motivation. Not surprisingly, human resource specialists attach even more importance to employee skills and education than finance directors: “Human capital actually starts with the people that we have, the calibre of skills, competencies and experiences that they either bring with them or that they evolve and create by the type of work they do with us” (Group HR Director of a FTSE Small Cap company operating in the industrial goods and services sector; Beattie and Smith, 2010, p. 270).

Within the relational capital category, all of the components investigated contribute to generating value to some extent according to marketing specialists. The top four components (customer relationships, company reputation, competitive edge in terms of quality of product/service, and data/knowledge of customers) were thought to be more important than anything else. Communication with which to build relationships and knowledge of customers appeared to be at the forefront of value creation for the marketing specialists:

p.289

Knowledge of customers is critical to understanding how our customers sell their products to their customers and how they market them. So the more you understand about how customers use our technology as part of their overall marketing message, the better we can actually promote our next technologies to them.

(VP of Marketing, FTSE Small Cap company operating in the Technology sector; Beattie et al., 2013, p. 34)

Relationships and communication with customers also appears to have additional benefits in acquiring knowledge essential to the development of a competitive edge: “Customers are incredibly willing to offer information about competitors’ products. So most of it comes from informal feedback from a customer” (Director of Business Development, main-market company operating in the technology sector; Beattie et al., 2013). Marketing specialists attach more importance to the contribution of individual relational capital components compared to finance directors, especially in terms of data/knowledge of customers and marketing strategies. Such differences in views are not surprising, and are likely to reflect the customer-orientated perspective of marketing specialists compared to the shareholder-orientated perspective of finance directors.

Benefits and costs of IC disclosure

This section considers both the benefits and costs of IC disclosure and the existence of a benefit versus cost trade-off.

Benefits of IC disclosure

According to the UK finance directors surveyed, the capital market benefits of IC disclosure dominate. Disclosing IC information to correct an undervalued share price was considered more important than anything else. According to the group financial report of a FTSE 100 healthcare firm:

The attitude of our senior management is to maintain clear communication with our investors so that there are no surprises … they want our share price to correctly value the business … it’s a very different culture from some aggressive corporates of the past where communication has been about enhancing share price beyond what it should be.

(Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 55)

Increasing the predictability of future prospects was next in terms of importance, with increasing price/earnings ratio and reducing information risk both being at least fairly important. The importance of capital market benefits documented here are not, however, unique to the IC context since previous research in the US has found voluntary disclosure in general is made in order to reduce information risk and boost stock price (Graham et al., 2005). UK finance directors have previously been found to voluntarily disclose for the benefit of obtaining a reputation for openness (Armitage and Marston, 2007). However, in the IC context in general, disclosure to promote a reputation for transparent and accurate reporting was considered below capital market considerations in terms of importance by finance directors. In the words of the group financial controller of a FTSE 250 firm operating in industrial goods and services, “We do pride ourselves on being, within reason, as transparent as possible to the market, and we hope that stands us in good stead, in terms of the value that the market attributes to us” (Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 55).

p.290

Certain companies were driven by the reputational benefits of IC disclosure in terms of responding to perceived unethical corporate behaviour. Communicating IC information to customers and other stakeholders was important where the nature of business encouraged it. As the group finance director of one FTSE 100 industrial goods and services company put it:

We get attacked by various pressure groups outside the organization saying [the nature of our business] is unethical. We have put it [ethics] higher up on the corporate agenda. We engage now you know, and we listen and … we change. In the early 90’s the test was if it’s legal that’s alright. The test isn’t that anymore, the test is how would it read on the front page of the Daily Mail, and would I be happy explaining this to my mum? The test for all businesses is much different from where the law sits … so you end up having to try and inform all those opinion formers.

(Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 56)

According to human resource specialists, attracting and retaining high calibre employees are the most important two benefits gained from disclosing human capital information. The disclosure of existing employee reputation is valuable to future recruitment. In this manner, value is created “through enhanced reputation and disclosure influences the external perception of reputation” (Toms, 2002, p. 258). As the assistant head of employee engagement at a FTSE 100 firm operating in the banking sector put it:

It’s very important that [the company] has as strong an external perception and reputation as we can have … we have done some work in the area of employer branding … the more people know about the good employee practices we do, the more they are hopefully likely to work for us.

(Beattie and Smith, 2010, p. 278)

The majority of finance directors did not rate creating trustworthiness with other stakeholders such as employees and customers as a significant benefit to IC disclosure. However, such benefits vary according to the type of IC information disclosed, being of more importance in relation to human and relational capitals, but not structural capital. According to the marketing specialists, the disclosure of customer relational capital information is most beneficial when creating trustworthiness with customers. It is also important in both retaining and attracting new customers. Trustworthiness with potential customers can be achieved by disclosing information about current customers. According to the director of business development for a main market company operating in the technology sector:

[t]he most powerful way to sell to a customer is a reference. You’ll typically always be asked for references within an industry. The most credible thing you can do with a customer is say we’ve done the same thing for somebody else in the same industry.

(Beattie et al., 2013, p. 41)

Through disclosure companies can, therefore, borrow their customer’s reputation to add value to their own (Helm and Salminen, 2010).

p.291

Costs of IC disclosure

A significant cost of IC disclosure is loss of competitive advantage in terms of divulging company secrets or otherwise harming competitive position, according to finance directors:

I’ll describe it [processes, our life cycle, management process] in the generality to investors but the forms we use and how we go about this is proprietary so we keep it … The sector is prone to industrial espionage by nations, not necessarily by individuals but by nations.

(Group finance director, FTSE 100 firm in industrial goods and services; Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 60)

We find ourselves in the fortunate position where we are probably sort of number one or number two in most of the markets we operate in … so we set the precedent for the development of the market … so we don’t want to give too much of what we are trying to achieve to our competitors.

(Group financial controller, FTSE 250 firm in industrial goods and services; Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 60)

The importance attached to the cost of loss of competitive advantage reinforces the findings of prior studies in both the UK (Armitage and Marston, 2007; Unerman et al., 2007) and elsewhere (Van Der Meer-Kooistra and Zijlstra, 2001; Gunther and Beyer, 2003; Graham et al., 2005).

The potential costs associated with creating unrealistic expectations and a disclosure precedent that is potentially difficult to maintain are also considered important. This is consistent with previous findings where Unerman et al. (2007) found that UK finance directors were concerned that investors and analysts would develop overly optimistic/pessimistic expectations from IC disclosures. The cost of information provision in terms of information collection and auditor opinion was also generally viewed as important.

Although the majority of finance directors surveyed viewed IC disclosure to be fairly to very important in terms of marketing their company products, being overtly seen to market via IC disclosure created a cost to be avoided in certain sectors. As the financial controller of a financial services company on the AIM market observed:

We’re not allowed to market … we cannot market … we need to be careful on our annual report about marketing … the FSA could clamp down on us and say you are marketing to the general public … talking up [your] products too much.

(Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 56)

The group financial reporter in a FTSE 100 company operating in healthcare had similar concerns: “The promotion and marketing of medicines is something that’s very regulated . . . legal obligations in terms of selling and marketing and promotion of our products . . . makes it different” (Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 57). These quotes serve to illustrate why it is important to avoid attracting unwanted scrutiny from regulators and other stakeholders when disclosing IC information.

Human resource specialists indicated that loss of competitive position was the most important cost to disclosing human capital information. As the group HR director of a FTSE Small Cap industrial and services firm acknowledged: “We report in our annual report and accounts carefully, because if you have got good people then other people want them” (Beattie and Smith, 2010, p. 276). The assistant head of employee engagement of a FTSE 100 Bank echoed such concerns:

p.292

We have a strong reputation externally and we place a very high value on our human capital team and our human capital strategy, that’s a competitive advantage for us. So we would be cautious to some degree in the level of information, the level of detail we would share with our competitors externally.

(Beattie and Smith, 2010, p. 276)

Marketing specialists were also most concerned with the costs associated with loss of competitive position when disclosing customer relational capital information. “With our competitors . . . we don’t actually want to tip them off . . . we don’t necessarily want to beat the drum and allow our competitors to go in to win them [new customers] over instead of working with us” (VP of Marketing, FTSE Small Cap company operating in the technology sector; Beattie et al., 2013, p. 43).

You do get some organizations that will put up an entire list of the entire customer base. I’ll never do that. All I do is go to my competitors and I copy those people and I go target them, because I now know they use those products.

(Director of Business Development, main market company operating in the Technology sector; Beattie et al., 2013, p. 43)

A further cost of disclosing customer relational capital exists in terms of eroding trustworthiness and relationships with existing customers who wish associated relationships to remain private. This was a major concern raised by the VP of Marketing of a FTSE Small Cap technology company:

We’ll only disclose stuff that is consistent with how they [the customers] are going to market and that is very, very important. In principal [sic], the more relationships we can talk about the better. However, it’s rather more complex because a lot of the time leading brands [our customers] do not want to disclose … the moment they start saying “well we got this technology from here and that technology from there”, that is diluting the strength of their brand.

(Beattie et al., 2013, p. 41)

Benefit versus cost trade-off?

Beattie and Smith (2012), through a statistical analysis of the finance director responses to a long list of benefits and costs associated with IC disclosure identified in previous academic literature, conclude that a limited set of benefits and costs are traded-off. In contrast to previous research (Van Der Meer-Kooistra and Zijlstra, 2001), the evidence does not suggest strongly that the costs of providing IC information outweigh the benefits.

Finance directors recognize that the benefits from disclosing IC information to investors in the capital market must be weighed against putting that same information in the hands of competitors. Sixty-two percent agreed or strongly agreed that “informing capital markets in relation to IC is balanced with the need to ensure that competitive advantage is not compromised” (Beattie and Smith, 2012, p.12). As the finance director and company secretary of a chemical company listed on the AIM market articulated:

p.293

I think it needs to be recognized in financial reporting that there is a fundamental conflict between confidentiality and competitively sensitive information, and providing information to investors … investors want to know what that is [competitive advantage] because that helps them to value the business, but competitors want to know … in order that they can knock it down and get around it somehow.

(Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 60)

The existence of a trade-off between the benefits of informing capital markets and the cost of loss of competitive advantage is also consistent with previous findings (for example, Unerman et al., 2007).

When specifically disclosing human capital information, the benefits in terms of acquiring new human capital are weighed against the cost of losing existing human capital to competitors. The benefits of disclosing customer relational capital information are recognized in the form of attracting new customers, building trust with those customers, and enhancing corporate reputation. However, the trade-off is the associated cost of delivering the sensitive information of customer identity straight into the hands of competitors. The director of business development for a main market technology company summarized this as follows: “You want to have as much information in the hands of your customers as possible and you want to have as little information in the hands of your competition as possible” (Beattie et al., 2013, p. 43). However, customer relational capital disclosure not only costs in terms of competitors, it costs in terms of damaged relationships with existing customers in situations when there is a desire to keep associations private.

To what extent is IC disclosure voluntary?

This section considers the extent to which IC disclosure is voluntary. An analysis of both financial reporting and narrative reporting requirements is provided. External restrictions outside of financial and narrative reporting requirements are also highlighted.

Financial reporting requirements

According to Roslender and Fincham (2001), it is unlikely that traditional financial reporting will be capable of accommodating IC. In the UK, international accounting standards are mandatory for listed companies when producing consolidated group accounts. New UK regulation in the form of Financial Reporting Standard 102 is an option for individually listed companies. For IC assets to be included in the statement of financial position (balance sheet), the IC assets would have to meet certain recognition criteria, namely that it is probable that expected future economic benefits attributable to the asset will flow to the entity and the cost or value of the asset can be measured reliably. Additionally, to be recognized, intangible assets (defined as ‘an identifiable non-monetary asset without physical substance’) must meet an identifiability criterion. This also has two aspects. First, the asset must be separable from the entity and second arise from a contractual or legal right (International Accounting Standard 38, IASB, 2004; Financial Reporting Standard 102, FRC, 2015). Consequently, IC is generally excluded from the traditional financial reporting framework because major components do not meet several of these criteria (Roos et al., 1998). On average, finance directors disagreed that IC reporting could be improved if the capitalization rules for intangible assets were made less restrictive. As the financial controller of a financial services AIM company protested: “Not on the balance sheet, because it’s just going to be too subjective and everyone’s going to have a different answer”.

p.294

Narrative reporting requirements

Given the exclusion of IC from the financial statements, a narrative disclosure approach has become accepted as an appropriate route to take (DATI, 2000, 2002). The financial statements are embedded within the annual corporate report which, despite the availability of various alternative communication channels, remains a key reporting document (Beattie, 1999).

It has been increasingly asserted, especially in the aftermath of the 2008 banking crisis, that financial statements should be complemented with narrative information that provides context for the financial information. This narrative information should inform stakeholders of the company’s business model in terms of what creates corporate value, including key risks, resources, and relationships, and also includes key performance indicators already used by management to manage the business. This term ‘business model’ increasingly features in the business reporting debate. According to Teece (2010), a business model conveys how a company converts resources into economic value. It captures all forms of a company’s capital, including physical, financial, and intellectual, so both the IC concept and the business model concept are mutually concerned with value creation. Therefore, IC disclosure is made, at least to some degree, through business model description and disclosure. Beattie and Smith (2013) describe the business model as the higher-level concept in value creation, driving IC disclosure in terms of what IC components are most crucial. This emphasis on narrative reporting, including business model reporting, has become increasingly global as more countries adopt International Financial Reporting Standards (FASB, 2009; ICAEW, 2009; EFRAG, 2010; BIS, 2011; IIRC, 2013). Indeed, the business model is central to the ever-evolving integrated reporting debate where the future of corporate reporting is said to depend on the ability to communicate how all forms of capital (financial, manufactured, intellectual, human, social, and natural) come together to create value.

In 2010, the IASB issued a Practice Statement on “management commentary”, which recommends that IC resources should be disclosed, significant relationships should be identified and discussed, with appropriate performance measures also disclosed (IASB, 2010). However, mandatory compliance is not currently required and, in the absence of any detailed rules or guidance, the nature and degree of any IC information voluntarily disclosed has the potential to exhibit significant variation across companies. A European Commission (EC) directive on the disclosure of non-financial information introduced in 2014 has future implications for around 6,000 large companies listed on EU markets.3 The directive requires the disclosure of relevant social, environmental, and board diversity information in annual reports from financial year 2017 onwards, capturing a degree of IC components. Guidelines are expected to be published by the EC in spring 2017. However, the guidelines are to be ‘non-binding’.

In the UK, the Corporate Governance Code, which is mandatory for listed companies under London Stock Exchange rules, requires company directors to “include in the annual report an explanation of the basis on which the company generates or preserves value over the longer term (the business model) and the strategy for delivering the objectives of the company” (UK Corporate Governance Code, FRC, September 2014, p. 16). This has been the case since 2010 and, on this basis, IC disclosure could be interpreted as mandatory. However, the mandatory business review required prior to 2013 included no specific requirements in relation to business models and IC. The UK Narrative Reporting Statement (ASB, 2006), which continued to influence corporate reporting in the UK, also encouraged discussion of resources such as IC. Subsequently, the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills (BIS) issued a consultation document in 2011 subsequently proposing that the reporting statement be revised to replace the business review and directors’ report with a high-level strategic report and annual directors’ statement. In August 2013, the government amended company law and UK listed companies must include a description of strategy and their business model in this new strategic report (The Companies Act 2006 (Strategic Report and Director’s Report) Regulations 2013, s. 414C,). BIS requested that the UK Financial Reporting Council prepare non-mandatory guidance supporting the new legal requirements for the strategic report. This guidance was subsequently published in 2014. As the EC requirements are similar to those of the strategic report, UK companies may also use this guidance to accommodate the EC directive.4 Although preparing a strategic report is mandatory, the FRC itself acknowledges that these regulations “represent a relatively modest change to pre-existing legal requirements” (FRC, 2014, p. 3). With both the UK strategic report and the EC directive, where the requirement for mandatory disclosure is accompanied by non-mandatory guidance on how to do so, the distinction between mandatory and voluntary is blurred.

p.295

Finance directors in the study described here viewed the narrative sections of the annual report as being highly appropriate for IC disclosure. Approximately 53 per cent viewed the annual report as an effective form for communicating human and structural capital, with 46 per cent considering it effective for communicating relational capital. Investor and analyst presentations and one-to-one meetings were thought to be even more effective for communicating all IC forms. Approximately 73 per cent of human resource specialists indicated the annual report was effective, and it was viewed by them as the most effective form for human capital disclosure. Although 66 per cent of marketing specialists viewed the annual report as effective in terms of marketing/customer relations information disclosure, its limitations were widely acknowledged: “Well it’s not the case of it [the annual report] isn’t effective, but it only reaches certain people” (VP of marketing for a FTSE Small Cap technology company; Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 127). “I absolutely view it [the corporate annual report] as a marketing document. But I understand the audience who it’s talking to is very limited to those who want to invest in your company, rather than take products out with you” (Head of marketing and UK retail marketing for a FTSE 250 financial services company; Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 127). Marketing specialists viewed company web pages as more effective than the annual report, with press releases a close contender. “Press releases are bread and butter for us and particularly when you look at how the web feeds have developed now. The press release will get quickly dropped into any number of e-newsletters and e-zines” (VP of marketing for a FTSE Small Cap technology company; Beattie and Thomson, 2010, p. 128).

For finance directors, the preferred nature of disclosure regulation governing the annual report was via a best practice statement, rather than mandatory requirements and via principles-based guidance, rather than detailed guidance/standardization. The finance director of an AIM chemical company explained why:

You can have fifteen companies making soap powder, and the soap powder may be almost identical to one another in terms of how clean they make your socks; but what will make fifteen companies different, and what will make some of them profitable and some of them unprofitable? It will be, how well do they treat their employees, do they have good employees, and do they value their good employees? If employees come up with good ideas do they implement them? If they have good formulations for new types of soap powder, are they effective in getting them into the market as new products, within innovative claims that then win market share? All these things are what creates value and each one of them will be unique, and that’s going to make it very difficult to quantify or to reflect in an annual report in any other way than through some sort of principal narrative disclosure.

p.296

The FRC has subsequently conducted a study on the impact of the Strategic Report (FRC, 2015). They conclude that business model reporting is still evolving, variation exists across companies, and although some companies provide good examples of disclosures explaining how corporate value is generated, there is a need for better explanation on what makes companies different. Such calls are without doubt aimed at “providing the information necessary for shareholders to assess the entity’s performance, business model and strategy” (FRC, 2014, p. 8). However, the evidence discussed previously in this chapter has already underlined that the benefits of IC disclosure to investors are balanced with the cost of loss of competitive advantage. On that basis, it is hardly surprising that the FRC finds companies reluctant to highlight what that competitive advantage is in their strategic reports. It has indicated that in the absence of mandatory rules, IC disclosure remains predominantly voluntary. Further, introducing mandatory rules could be viewed in terms of a ‘double-edged sword’. Investor stakeholders may indeed benefit from additional IC disclosure but at what ultimate cost to their pockets when loss of proprietary information diminishes value creation and potential competitors jump on the corporate band wagon? Consequently, it is well documented in the disclosure literature that one of the principal reasons why mandatory rules are resisted is the concern regarding the commercial sensitivity of disclosures.

External restrictions outside financial and narrative reporting regulations

When considering the costs of IC disclosure earlier in this chapter, it was highlighted that industry regulations restricted the voluntary disclose of certain IC information. Examples in point were the financial services industries and healthcare where companies were restricted in terms of product promoting. The healthcare sector also seems somewhat restricted in terms of disclosing who it provides products to. This was emphasized by the group development director of a FTSE Small Cap company:

We work with [a particular government department], we provide services to the [government department], the [government department] as a brand is hugely valuable to us but it’s hugely valuable to the [government department] and they will therefore in contracts often limit, or try to limit, what we are allowed to say and how we are allowed to use the [government department’s] brand in our own materials.

(Beattie et al., 2013, p. 41)

In certain contexts, national legislation prevents the disclosure of, for example, customer relationships. The group finance director of a FTSE 100 company operating in the industrial goods and services sector provides an illustration: “We operate on the Official Secrets Act and the various classifications that come back with that with various work. So we know what we can disclose and we know what we can’t” (Beattie et al., 2013, p. 44). Further, finance directors indicated that they are increasingly finding themselves in situations where legal restrictions imposed by individual customers prevent customer relationships being disclosed:

p.297

Most of our North American customers will now contractually explicitly forbid us to ever use their name or the fact that they’d done business with us in any communication without prior consent. Constraints placed on us by customers as to how/where/when we are allowed to use information about our relationship with them. Typically, this is part of the contract agreement and has changed from unusual to normal over the past few years.

(Director of Business Development, main market technology company; Beattie et al., 2013, p. 44)

However, the existence of non-disclosure agreements is not necessarily an absolute barrier. As the VP of marketing for a FTSE Small Cap technology company indicated: “You can’t hang everything back to a contract. The reality is these things are never black and white and you’ve just got to understand and toe the line” (Beattie et al., 2013, p. 44). These various external restrictions and regulations placed on the IC disclosure decision, arising from customer-specific non-disclosure agreements and generic legislation, make mandatory disclosure rules impossible, as two inconsistent sets of legal imperatives would result.

Concluding remarks

Prior indirect content analysis research, based on the extent of its observed disclosure, suggests that relational capital is the most valuable IC category. In the study reported here, using questionnaire survey responses from UK finance directors, human capital was ranked as providing the highest contribution to value creation overall. Further, employee skills and education was in the top four components with three relational capital components (customer relationships, competitive edge in terms of product/service quality, and company reputation). The overall importance of human capital is consistent with the position taken by the DTI (2003) in the Accounting for People Task Force. However, it sits in stark contrast to the findings from content analysis studies, where disclosure is focused on relational capital.

This chapter focuses on benefits, costs, and restrictions and finds that they are unequally associated with disclosure across the spectrum of IC information. This explains why IC components observed to be disclosed are not necessarily those which are the most important in the value creation process. There is strong evidence to confirm the existence of a trade-off between benefits of informing capital investors versus the cost of loss of competitive advantage. However, the corporate disclosure decision is not entirely within the remit of the external financial reporting function, since other functional specialists such as marketing and human resources also play a central role in the corporate communication process. The benefits of attracting new human capital are traded against the cost of losing existing human capital to competitors. Disclosing customer relationship information attracts new customers and enhances trust and reputation, but these benefits must be traded-off against delivering sensitive customer information to competitors and damaging trust and relationships with existing customers.

The extent to which IC disclosure is voluntary depends on the existence of specific mandatory narrative reporting requirements. The IASB’s management commentary is not mandatory and, in the UK, although there is a mandatory requirement for a strategic report, the accompanying guidance is non-mandatory. The same can be said in relation to the EC directive on the disclosure of non-financial information. The existence of mandatory reporting requirements is, therefore, blurred and IC reporting in corporate annual reports is perceived as predominantly voluntary. However, IC disclosure cannot be said to be voluntary, if private disclosure agreements or other legal restrictions/regulations, outside the narrative reporting arena are in place to safeguard highly sensitive information from the public domain. Further, in this modern communication era, Dumay and Guthrie (2017) highlight that both risks and opportunities arise outside the reporting entity via “involuntary disclosures produced by stakeholders and stakeseekers” (p. 40).

p.298

In short, IC disclosure decisions are increasingly complex given the spectrum of different benefits, costs, trade-offs, restrictions, risks, and opportunities in place. This chapter has served to emphasize that IC disclosure in itself has the power to enhance corporate value through the benefits it brings. However, IC disclosure needs to be carefully managed given the associated costs that potentially destroy value. IC disclosure appears to involve successfully negotiating a fine line indeed; a fine line that separates value creation and value destruction in this brave new narrative reporting world. At the heart of this new narrative reporting world sits IC through its contribution to the business model central to the integrated reporting debate, and through new narrative disclosure regulation such as the EC directive and the UK strategic report. Future research presents the opportunity to understand how the most important IC components identified in this chapter contribute to the overall business model itself. The opportunity also arises to explore the extent to which it is possible to manage the disclosure benefits and costs identified, particularly in terms of disclosing competitive advantage in a manner that is both understood and satisfies investors, whilst inhibiting replication by competitors. The latter appears to be a pivotal issue going forward in the regulation of business model disclosures. Investigating the management of ‘involuntary’ disclosures in the value creation process has also been advocated as a fruitful new future IC research direction (Dumay and Guthrie, 2017).

Notes

1 See Appendix 1 of Beattie and Thomson (2010) for a list of 128 such components.

2 This evidence is currently fragmented across several publications (Beattie and Smith, 2010, 2012; Beattie and Thomson, 2010; Beattie et al., 2013) which individually address separate aspects. This chapter brings a holistic analysis of this evidence with new interpretative commentary, particularly in relation to recent developments in the narrative reporting arena. Previously unpublished interview material extends the illustration of key points being made.

3 Companies with more than 500 employees.

References

Abdolmohammadi, M. J. (2005), “Intellectual capital disclosure and market capitalization”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 397–416.

Abeysekera, I. (2006), “The project of intellectual capital disclosure: Researching the research”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 61–77.

Abeysekera, I. (2008), “Motivations behind human capital disclosure in annual reports”, Accounting Forum, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 16–29.

Abeysekera, I. and Guthrie, J. (2005), “An empirical investigation of annual reporting trends of intellectual capital in Sri Lanka”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 151–163.

p.299

Accounting Standards Board (ASB) (2006), “Reporting Statement 1: Operating and Financial Review”, available at: www.frc.org.uk/images/uploaded/documents/Reporting%20Statements%20OFR%20web.pdf (accessed 15 January 2012).

April, K. A., Bosma, P., and Deglon, D. A. (2003), “IC measurement and reporting: Establishing practice in SA mining”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 165–180.

Armitage, S. and Marston, C. (2007), Corporate Disclosure and the Cost of Capital: The Views of Finance Directors, ICAEW Centre for Business Performance, London.

Ashton, R. H. (2005), “Intellectual capital and value creation: A review”, Journal of Accounting Literature, Vol. 24, pp. 53–134.

Beattie, V. (1999), Business Reporting: The Inevitable Change? Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, Edinburgh, UK.

Beattie, V. and Smith, S. J. (2010), “Human capital, value creation and disclosure”, Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 262–285.

Beattie, V. and Smith, S. J. (2012), “Evaluating disclosure theory using the views of UK finance directors in the intellectual capital context”, Accounting and Business Research, Vol. 42, No. 5, pp. 1–24.

Beattie, V. and Smith, S. J. (2013), “Value creation and business models: Refocusing the intellectual capital debate”, British Accounting Review, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 243–254.

Beattie, V. and Thomson, S. (2010), Intellectual Capital Reporting: Academic Utopia or Corporate Reality in a Brave New World?, Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, Edinburgh, UK.

Beattie, V., Roslender, R., and Smith, S. J. (2013), “Balancing on a tightrope: Customer relational capital, value creation and disclosure, Financial Reporting, Vol. 3–4, pp. 17–50.

BIS (2011), The Future of Narrative Reporting: A Consultation, Available at: http://bis.gov.uk/Consultations/future-of-narrative-reporting-further-consultation (accessed 6 January 2012).

Bontis, N. (2003), “Intellectual capital disclosure in Canadian corporations”, Journal of Human Resource Costing and Accounting, Vol. 7, No. 1–2, pp. 9–20.

Bozzolan, S., Favotto, F., and Ricceri, F. (2003), “Italian annual intellectual capital disclosure”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 543–558.

Bozzolan, S., O’Regan, P., and Ricceri, F. (2006), “Intellectual capital disclosure (ICD): A comparison of Italy and the UK”, Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 92–113.

Brennan, N. (2001), “Reporting intellectual capital in annual reports: Evidence from Ireland”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 423–436.

Campbell, D. and Abdul Rahman, M. R. (2010), “A longitudinal examination of intellectual capital reporting in Marks & Spencer annual reports, 1978–2008”, British Accounting Review, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 56–70.

Chaminade, C. and Roberts, H. (2003), “What it means is what it does: A comparative analysis of implementing intellectual capital in Norway and Spain”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 733–751.

Danish Agency for Trade and Industry (DATI) (2000), A Guideline for Intellectual Capital Statements: A Key to Knowledge Management, DATI, Copenhagen.

Danish Agency for Trade and Industry (DATI) (2002), Intellectual Capital Statements in Practice: Inspiration and Good Advice, DATI, Copenhagen.

Deegan, C. (2000), Financial Accounting Theory, McGraw-Hill, Sydney, Australia.

Department for Trade and Industry (DTI) (2003), Accounting for People, Task Force Report, Department for Trade and Industry, London.

Dumay, J. and Guthrie, J. (2017), “Involuntary disclosure of intellectual capital: Is it relevant?” Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 29–44.

Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M. (1997), Intellectual Capital: The Proven Way to Establish your Company’s Real Value by Measuring It Hidden Brain Power, Piatkus, London.

EFRAG (2010), The Role of the Business Model in Financial Reporting, European Financial Reporting Advisory Group, Brussels.

Elliott, R. K. and Jacobson, P. D. (1994), “Costs and benefits of business information disclosure”, Accounting Horizons, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 80–96.

FASB (2009), Disclosure Framework, Financial Accounting Standards Board, Norwalk, CT.

FRC (2014), Guidance on the Strategic Report, available at www.frc.org.uk/Our-Work/Publications/Accounting-and-Reporting-Policy/Guidance-on-the-Strategic-Report.pdf (accessed 4 July 2016).

p.300

FRC (2015), Clear Concise Developments in Narrative Reporting, available at: www.frc.org.uk/Our-Work/Publications/Accounting-and-Reporting-Policy/Clear-Concise-Developments-in-Narrative-Reporti.aspx (accessed 4 July 2016).

Goh, P. C. and Lin, K. P. (2004), “Disclosing intellectual capital in company annual reports Evidence from Malaysia”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 3, pp. 500–510.

Graham, J. R., Harvey, C. R., and Rajgopal, S. (2005), “The economic implications of corporate financial reporting”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 40, No. 1–3, pp. 3–73.

Gunther, T. and Beyer, D. (2003), Hurdles for the Voluntary Disclosure of Information on Intangibles: Empirical Results for New Economy Industries, Dresden Papers of Business Administration, No. 71/03, Germany.

Guthrie, J. and Petty, R. (2000), “Intellectual capital: Australian annual reporting practices”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 1, No. 3, pp. 241–251.

Guthrie, J., Petty, R., and Ricceri, F. (2007), External Intellectual Capital Reporting: Evidence from Australia and Hong Kong, Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, Edinburgh, UK.

Habersam, M. and Piper, M. (2003), “Exploring intellectual capital in hospitals: Two qualitative case studies in Italy and Austria”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 753–779.

Heitzman, S., Wasley, C., and Zimmerman, J. (2010), “The joint effects of materiality thresholds and voluntary disclosure incentives on firm’s disclosure decisions”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 49, No. 1–2, pp. 109–132.

Helm S. and Salminen R. T. (2010), “Basking in reflected glory: Using customer reference relationships to build reputation in industrial markets”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 39, No. 5, pp. 737–743.

IASB (2004), Intangible Assets, International Accounting Standard No. 38, IASB, London.

IASB (2010), Management Commentary, Practice Statement, available at: www.ifrs.org/Current+Projects/IASB+Projects/Management+Commentary/IFRS+Practice+Statement/IFRS+Practice+Statement.htm (accessed 6 January 2012).

ICAEW (2009), Developments in New Reporting Models, Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, London.

International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC) (2013), The International <IR> Framework, International Integrated Reporting Council, London.

Lev, B. (2004), “Sharpening the intangibles edge”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 82, No. 6, pp. 109–116.

Li, J., Pike, R., and Haniffa, R. (2008), “Intellectual capital disclosure and corporate governance structure in UK forms”, Accounting and Business Research, Vol. 38, No. 2, pp. 127–159.

Lundholm, R. and Van Winkle, M. (2006), “Motives for disclosure and non-disclosure: A framework and review of the evidence”, Accounting and Business Research, International Accounting Policy Forum, Vol. 36, pp. 43–48.

Meritum, (2002), “Guidelines for managing and reporting on intangibles”, Meritum, Fundación Aritel Móvil, Madrid.

Mouritsen, J., Larsen, H. T., and Bukh, P. N. D. (2001), “Intellectual capital and the ‘capable firm’: Narrating, visualising and numbering for managing knowledge”, Accounting, Organizations & Society, Vol. 26, No. 7–8, pp. 735–762.

Patten, D. M. (1991), “Exposure, legitimacy and social disclosure”, Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 297–308.

Richardson, A. J. and Welker, M. (2001), “Social disclosure, financial disclosure and the cost of equity capital”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 26, No. 7–8, pp. 597–616.

Roos, G., Roos, J., Edvinsson, L., and Dragonetti, D. C. (1998), Intellectual Capital Navigating in the New Business Landscape. New York University Press, New York.

Roslender, R. and Fincham, R. (2001), “Thinking critically about intellectual capital accounting”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 383–399.

Roslender, R. and Fincham, R. (2004), “Intellectual capital accounting in the UK: A field study perspective”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 178–209.

Striukova, L., Unerman, J., and Guthrie, J. (2008), “Corporate reporting of intellectual capital: Evidence from UK companies”, British Accounting Review, Vol. 40, No. 4, pp. 297–313.

Teece, D. J. (2010), “Business models, business strategy and innovation”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, No. 2–3, pp. 172–194.

p.301

Toms, J. S. (2002), “Firm resources, quality signals and the determinants of corporate environmental reputation: Some UK evidence”, British Accounting Review, Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 257–282.

Unerman, J., Guthrie, J., and Striukova, L. (2007), UK Reporting of Intellectual Capital, ICAEW Centre for Business Performance, London.

Van der Meer-Kooistra, J. and Zijlstra, S. M. (2001), “Reporting on intellectual capital”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 456–476.

Vandemaele, S. N., Vergauwen, P. G. M. C., and Smits, A. J. (2005), “Intellectual capital disclosure in the Netherlands, Sweden and the UK: A longitudinal and comparative study”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 417–426.

Vergauwen, P. G. M. C. and Van Alem, F. J. C. (2005), “Annual report IC disclosures in The Netherlands, France and Germany”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 89–104.

Verrecchia, R. E. (2001), “Essays on disclosure”, Journal of Accounting and Economics, Vol. 31, No. 1–3, pp. 97–180.