Figure 20.1 The model to assess and monitor environmental and social initiatives

p.316

A MANAGEMENT CONTROL SYSTEM FOR ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL INITIATIVES

An intellectual capital approach

Paola Demartini and Cristiana Bernardi

Introduction

Over recent decades, commitment to corporate sustainability has been gaining prominence worldwide. In response to recent corporate scandals there has been increasing pressure on enterprises to integrate into organizational management the three pillars of sustainability: economic, environmental, and social. As a consequence, many companies have strengthened their commitment to provide external stakeholders, such as fund providers, customers, suppliers, employees, local communities, and government, with supplementary non-financial statements, along with traditional accounting reporting (e.g. Gray and Milne, 2002; Kolk, 2004, 2008; Guthrie et al., 2008; Dumay et al., 2016). The main aim of such voluntary disclosure is to shed light on firms’ value creation/destruction and distribution processes (Gray, 2006).

In addition, these sustainability reports can be regarded as a means of communication to those investors who determine their portfolios’ asset allocation on the basis of a company’s commitment to the concept of sustainability. Environmental and social initiatives (also called socially responsible investments) provide investors with further insight into corporate sustainability performance. Within this context indices linked to financial markets that systematically assess the environmental, social, and economic performance of corporations have been developed (e.g. Lòpez et al., 2007; Searcy and Elkhawas, 2012). Among these, of particular prominence are the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices and the FTSE4Good Index (Cerin and Dobers, 2001; Knoepfel, 2001; Chatterji and Levine, 2006).

In our chapter, attention is focused on a company operating in the global aerospace and defence industry, the top management of which had planned to increase its committment to corporate sustainability. The analysed entity, entirely owned by a listed multinational Italian company, is an international leader in electronic and information technology and designs and develops large systems for homeland protection, systems and radars for air defence, battlefield management, naval defence, air and airport traffic management, and coastal/maritime surveillance. Expertise and knowledge are crucial to the firm’s success, as the work is highly specialized. Moreover, companies in the industry are obliged to adhere to strict regulations involving national security, export restrictions, and licensing for military goods, accounting rules, and safety requirements. Detailed information about the company, which is not necessary for the discussion of our findings, is not provided. Authorization for access to the company and its data was obtained with the proviso of guaranteeing anonymity of the company and its personnel.

p.317

In 2010 the holding company of the high-tech group, the shares of which are listed on the Milan Stock Exchange and on the New York Stock Exchange, was selected as an index component of the Dow Jones Sustainability Indices (DJSI), and has maintained its membership for seven years in a row. As a consequence, top management decided to issue a master plan so as to implement specific sustainability initiatives while looking for a financial rationale to justify this decision. Each initiative was subject to measurement, evaluation, and reporting through the intellectual capital (IC) lens. Therefore, our research aims to answer the following question: how can environmental and social initiatives be identified, assessed, and monitored to improve corporate performance?

In order to answer the research question, we propose a management control system that provides a link between sustainability-oriented projects and corporate intangible assets (hereafter referred to as IC) in order to create value for sustainable development. In particular, we argue that the adoption of a management control system might have a positive impact not only on firms’ financial performance, but also on the assessment process companies are subject to for inclusion in sustainability indices. From a methodological point of view, the investigation is the result of a research project carried out together with the top management of the analysed company. Therefore, it takes an action research perspective.

Literature review and research framework

In order to establish the framework underpinning the proposed model for a mangement control system, the following three streams of research are considered. First, managing IC for organizational value creation. Second, developing sustainability management control systems. Third, managing socially responsible investments and sustainability indices.

Managing IC for organizational value creation

The construct of IC – defined by Stewart (1997) as knowledge, information, intellectual property, and experience, which can be exploited in order to generate wealth – offers a means to visualize, assess, and measure the knowledge accumulated within the firm, also referred to as ‘intangible resources’ or ‘intangible assets’. In line with Dumay (2016), we maintain that IC should also encompass environmental and social knowledge, as well as the information and IC to be managed for the purposes of meeting social requirements, improving business competitiveness, and enhancing corporate performance.

In the current globalized competitive arena, IC is a source of competitive advantage as it improves innovation, competitive differentiation, and organizational learning (e.g. Petty and Guthrie, 2000, p. 155; Guthrie, 2001; Marr et al., 2004a, 2004b; Mouritsen and Larsen, 2005; Subramaniam and Youndt, 2005; Ricceri, 2008; Schiuma et al., 2008; Montemari and Nielsen, 2013; Dumay and Roslender, 2013; Zakery et al., 2017). IC is categorized into three sub-components: human capital, structural capital, and relational capital (Saint-Onge, 1996; Roos et al., 1997; Stewart, 1997; Sveiby, 1997; Bontis, 1998). Human capital is defined as the knowledge acquired from people’s experiences, capabilities, skills, creativity, and innovativeness (Sveiby, 1997). It has been argued that it comprises the knowledge that employees take with them when they leave the firm; however, even if not owned or even controlled by the firm, it is considered as the most significant element of IC, since it is the driving force of the other two components. By contrast, structural capital is referred to as “what is left in the organization when people go home in the evening” (Roos and Roos, 1997, p. 415), the storehouses of knowledge that are embedded in systems, databases, and programs (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997). Lastly, relational capital reflects the idea that firms are not isolated systems, rather they depend, to a great extent, on the continuous interplay with the external environment. Therefore, relational capital consists of all the knowledge embedded in relationships with external parties such as customers, suppliers, partners, and other external stakeholders (Roos et al., 1997). Brand, image, and corporate reputation, for example, fall into this category.

p.318

Researchers and consultants have studied the advantages of IC management on companies’ organizational value creation (Guthrie et al., 2001; Dumay, 2016, pp. 169–171; Dumay et al., 2017). However, the effectiveness of IC management on organizational performance, both financial and non-financial, is difficult to achieve and assess (Dumay, 2012). Thus, our investigation aims to contribute to the debate concerning the impact of IC management on organizational business performance.

Sustainability management control systems

The development of environmental and social accounting has contributed to sustainability management and reporting (Bebbington and Gray, 2001; Gray, 2010). Many academics and practitioners have developed performance measurement systems, including the Performance Pyramid (Lynch and Cross, 1991), Balanced Scorecard (Kaplan and Norton, 1992), Performance Prism (Neely et al., 2002) and Sustainability Balanced Scorecard (Figge et al., 2002; Dias-Sardinha and Reijnders, 2005; Schaltegger and Wagner, 2006; Hubbard, 2009).

Management control is essential in promoting corporate sustainability (Schaltegger and Wagner, 2006; Gond et al., 2012) and academics are increasingly calling for empirical research on the role of management control systems in relation to environmental and social activities undertaken by organizations (e.g. Ferreira et al., 2010; Henri and Journeault, 2010; Schaltegger, 2011; Gond et al., 2012). Accordingly, Perez et al. (2007) claim that sustainability-oriented activities must be integrated into the firm’s strategic processes in order to translate environmental and social performance into long-term shareholder value. Nevertheless, to date few empirical studies have investigated how management control systems have been deployed in practice to promote corporate sustainability (e.g. Perego and Hartmann, 2009; Henri and Journeault, 2010; Riccaboni and Leone, 2010; Arjaliès and Mundy, 2013).

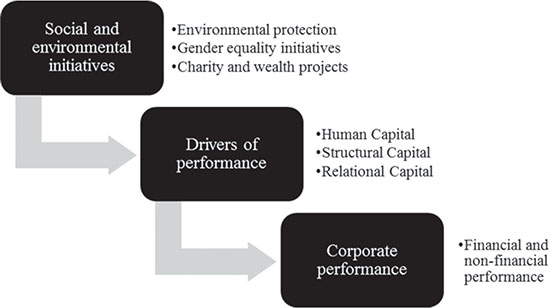

The purpose of this chapter is the proposal of a management control system that attempts to embed an IC perspective to identify, measure, and manage environmental and social initiatives (e.g. environmental protection, gender equality initiatives, charity, and wealth projects). An assumption underlying our investigation is that embedding environmental and social aspects into corporate strategy supports firms in the process of IC accumulation, such as skills and competencies, knowledge and innovation, legitimacy, trust, and reputation (Perrini et al., 2011). More specifically, we posit that IC plays a crucial role in mediating the relationship between the management of sustainability-oriented activities and corporate financial performance (Surroca et al., 2010; Demartini et al., 2014, 2015; Lin et al., 2015; Ferrero et al., 2016).

The literature review carried out by Guthrie et al. (2012, p. 75) reveals that management accounting has been the most popular focus of IC accounting research since the mid 2000s, covering a wide range of management-related subjects. In their conclusions, the authors call for “more critical field studies which will provide empirical studies of IC in action and help develop broader theoretical research” (p. 79). The need for a bottom-up performative approach to IC has also been advocated by Dumay and Garanina (2013) and Dumay (2013). It has indeed been contended that the adoption of such a perspective would benefit researchers and practitioners alike, since it would enable them to gain greater insights into how IC works within a specific organization (Mouritsen, 2006). Hence, our research aims to contribute to the ongoing debate on IC practices in action.

p.319

Managing socially responsible investments and sustainability indices

The phenomenon of socially responsible investment reflects the increasing concerns of investors towards environmental, social, ethical, and corporate governance issues. The growing awareness that ‘sustainable’ investments might produce better financial performance has indeed prompted numerous companies to publish voluntarily sustainability reports with the aim of guiding, at least in part, investment decisions (e.g. Magness, 2010; Berthelot et al., 2012). Quoting Boiral (2013, p. 1036), “Sustainability Reporting has become an increasingly common practice in companies’ attempts to respond to expectations, pressures and criticisms from stakeholders who want to be better informed about the environmental and social impacts of business activities”.

With the aim of providing guidance for investors seeking further insight into sustainability performance, many sustainability indices have been designed to measure the performance of those firms that set industry-wide best practices with regard to sustainability. Sustainability indices provide meaningful signals of social legitimacy in the attempt “to verify that a firm’s goals and actions align with societal values such as environmental sustainability, labour and human rights, anti-corruption practices, and community engagement” (Hawn et al., 2011, p. 3). It has indeed been argued that they serve as informational intermediaries between companies and their stakeholders (such as analysts, brokers, and financial institutions) by evaluating the disclosed sustainability related information (Robinson et al., 2011). From the investor’s point of view, such indices allow the identification of the world’s sustainability leaders for different industries, thus enabling regional and global benchmarking.

Within the realm of sustainability indices, the most widely recognized are the DJSI Family and the FTSE4Good. Established in 1999 and maintained collaboratively by RobecoSAM and S&P Dow Jones Indices, the DJSI family tracks the performance of the world’s largest companies leading the field in terms of corporate sustainability, defined by RobecoSAM (2013) as “a company’s capacity to prosper in a hypercompetitive and changing global business environment”. Since its inception, RobecoSAM has been conducting the annual Corporate Sustainability Assessment, which consists of an analysis of the sustainability performance of more than 2,500 companies covering the major indices. The assessment, based on information provided by the companies through the online questionnaire, is built on a range of financially relevant sustainability criteria covering the economic, environmental, and social dimensions. Nevertheless, as pointed out by Fowler and Hope (2007) and more recently by Searcy (2012), little is currently known about what impact sustainability indices have, in practice, on management control systems and what steps corporations have taken to be or remain included in the DJSI.

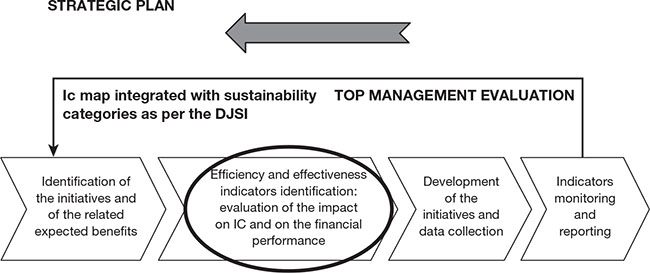

As a second assumption, we deem that a sustainability-oriented management control system could have a significatively positive impact on the assessment process companies are subject to for inclusion in the DJSI. Drawing on the above considerations, the joint team, made of professionals and academics, designed a management control system focusing particularly on i) the process by which environmental and social initiatives increase IC, and ii) how this might have a positive impact on corporate performance. In Figure 20.1, we sketch the model that will be analysed later in this chapter.

p.320

Figure 20.1 The model to assess and monitor environmental and social initiatives

Research method

The selection of a company belonging to the aerospace and defence sector is consistent with our research aim, since the field comprises high-tech global firms whose products and services result from investments in financial, human, structural, and relational capital. In particular, we focus on the case of a large company headquartered in Italy. Specifically, the analysed entity, entirely owned by a listed multinational Italian company, designs and develops large systems for homeland protection systems and radars for air defence, battlefield management, naval defence, air and airport traffic management, and coastal and maritime surveillance.

In recent years, the company’s top management has shown an interest in enhancing the company’s IC potential. To this end, an organizational unit was established entirely devoted to promoting product innovation, increasing patents and trademarks, strengthening personnel competencies, and enabling academic relationships. Moreover, the company’s top management expressed willingness to adopt an IC measurement approach through collaborations with researchers, and this allowed us to be involved in a business project that aimed to identify, measure, and manage the firm’s intangible resources. As a consequence, the investigation was conducted as action research (Dumay, 2010; Dumay and Baard, 2017). Given the strategic sector within which the company operates, detailed information about the company profile – not relevant in order to discuss our findings – will not be provided.

According to Reason and Bradbury (2006, p. 1), action research is a process that “seeks to bring together action and reflection, theory and practice”. Consistent with the interpretative approach, this is a case study whereby the researchers cooperate with the host organization, promoting solutions to actual problems and contributing to theory at the same time (Jönsson and Lukka, 2005; Dumay, 2010). In its traditional sense, action research “involves a collaborative change management or problem solving relationship between researcher and client aimed at both solving a problem and generating new knowledge” (Coghlan and Brannick, 2010, p. 44). Action research adopts a scientific approach to studying the resolution of social or organizational issues together with those who experience these issues directly. One of its main objectives is to increase understanding on the part of the researcher or the client personnel, or even both. Therefore, the researcher is intended to act in concert with the host organization: s/he observes the whole process and the related outcomes, and analyses the findings in light of the relevant literature.

p.321

Action research as a methodology not only reflects on the observations of the researcher, but also on the impact the interventions have on the organization. The main benefit for the researcher is the ability to develop insights into the implementation of new management innovations within organizations. For practitioners, the benefit is to gain the assistance and knowledge of academics as a resource in the implementation process (Dumay, 2010). Therefore, action research contributes to both research and practice.

There is not an agreed set of methodological protocols, or rules, shared by all researchers; however, action research usually begins with the establishment of initial contact between the researcher(s) and the representatives of the organization (Entry Stage). Diagnosis is a pivotal stage in action research, as the researcher(s) may introduce organizational members to conceptual schemes and/or theories that enable them to reinterpret how they perceive their situation. The ultimate goal of this phase is to develop a conscious understanding among organizational members and to co-determine and plan possible interventions. The intervention stage follows, during which both practitioners and researchers try to implement management innovation within the organization.

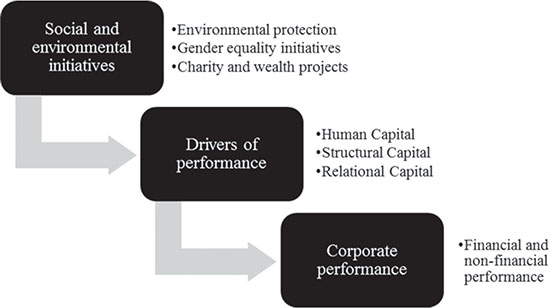

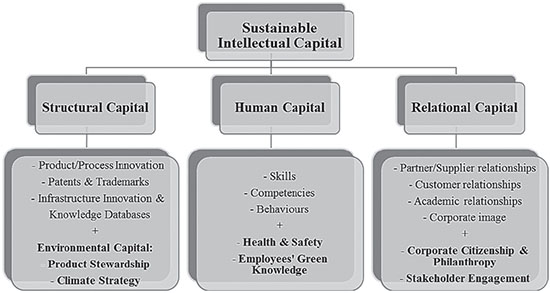

The research project lasted for five years (from 2010 to 2014). The project team was made up of three professionals belonging to the organizational unit devoted to the enhancement of IC (project controllers or ‘go-to’ persons) and three academics. Among the latter were the supervisors of this project, who were its sponsors and ‘gatekeepers’ (Dumay, 2010, p. 54). The supervisors helped facilitate access to the company. The ‘go-to’ persons helped the researchers become ‘insiders’, thus facilitating their taking part in the everyday processes and activities and working to “develop participatory interactions more akin to the interventionist process required for the conduct of interventionist research”, consistent with Dumay (2010, p. 55). Table 20.1 summarizes the steps undertaken by the joint team to develop the project, the information collected, and the main outcomes.

The researchers were involved in decisions and actions aimed at achieving objectives with the managers. The researchers’ involvement is consistent with an interventionist approach, in which participant observation is the main ‘research weapon’ used (Chiucchi and Dumay, 2015). Nevertheless, data was also collected through interviews and the review of internal documents (Jönsson and Lukka, 2005; Dumay, 2010). Between January 2010 and December 2013, the researchers attended 48 meetings running on average for 4 hours each. Additionally, the researchers recorded and transcribed semi-structured interviews along with field notes.

The research began with the identification of the problems perceived within the organization, before recognizing the ‘the client/stakeholder’ figure, and the agreement on who, how, where, and when they would take part in the research. The first issue was the identification of the main user of IC information, which in the analysed case study was identified as the company’s top management. Although the disclosure of IC information to external stakeholders is a further important aim, it was not taken into consideration since the research mainly focused on the managerial decision-making process (if only because the company is a subsidiary that does not produce separate financial statements for public consumption).

p.322

Table 20.1 Activities and main outcomes

p.323

The primary role of researchers was to introduce the IC conceptual scheme and related theories to organizational members (thus enabling them to reinterpret how they understood their company). The main role of practitioners was the assessment of their usefulness in practice. The ultimate goal of the joint research group was proposing to the company’s top management a model for the measurement and management of the firm’s intangible assets within a sustainability framework. Both the researchers and the controllers shared the responsibility of delivering the project’s output. Such a model, deriving from the joint effort of the research team, could therefore be integrated into managerial practices in support of the decision-making process.

Analysis and findings

In this section we present the model for the measurement and management of the company’s IC that the company’s top management decided to implement in order to control the specific sustainable management initiatives planned for 2014.

Managing IC within a sustainability framework

In this case study, the researchers’ involvement occurred in two distinct periods. From 2010 to 2012 the researchers were involved in designing and developing an IC measurement system leading to the publication of an internal IC report to manage intangible resources that had to be reinforced or acquired in response to the management’s suggestions and that support the strategic objectives of the company (see Demartini and Paoloni, 2013).

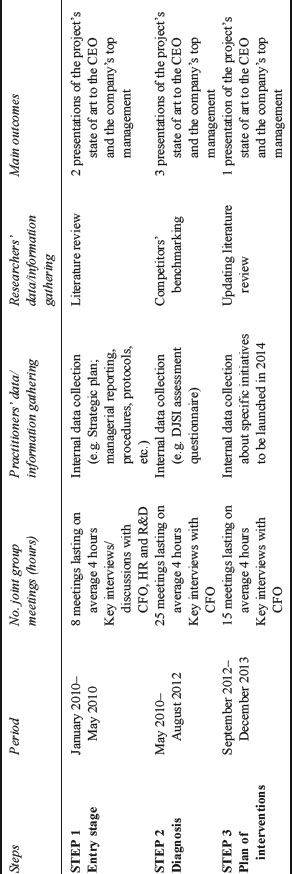

From late 2012 to the end of 2013, the functionality of the model outlined for measuring, reporting, and managing IC was broadened in order to take into account sustainability. In fact, following the changes in the parent company’s top management team and the inclusion of the holding company in the DJSI, sustainability became a primary strategic objective of the group. Thus, in 2013, management issued a master plan to implement specific sustainability initiatives while looking for a financial rationale to justify this decision. Each initiative was subject to measurement, evaluation, and reporting through the IC lens. Each project launched by the company that had a relevant impact on IC underwent calculation, evaluation, and reporting. The traditional vision of IC was used in the three areas represented by structural, human, and relational capital (see Figure 20.2). On the one hand, the application of the model represents a managerial innovation for the company’s single unit, whereas on the other, it offers a powerful reporting tool for the firm as a whole. It is worth noting that while the management control system design was completed in 2013, its deployment in practice was carried out in 2014.

Figure 20.2 Implementing sustainability categories as per the DJSI in the company’s IC map

p.324

Managing environmental and social initiatives

The research group elaborated a process for the identification of an efficient management tool to implement the new model into the management control of specific initiatives. The benefits of these initiatives (i.e. the projects launched by the company to foster sustainability performance, but not only these) should not be only measured by current financial indicators, because their output impacts intangible resources that are ‘mediating variables’ for expected financial benefits in the longer term.

The process follows an annual cycle starting from strategic planning, and then develops into subsequent stages, as shown in Figure 20.3. The circular process means the results return to the firm’s management through a feedback report that can be used in order to make changes where and if necessary.

Specifically, the activities are:

• identification of the main initiatives that have a significant impact on IC, including sustainability aspects and analysis of their related expected benefits;

• IC measurement, which implies the identification of the relevant resources that will be reinforced and/or acquired through the development of specific activities;

• implementation of the initiatives and data gathering; and

• reporting, that is, a document containing the results of the measurement and assessment activity of the projects to be sent to the firm’s top management at the end of the year.

This is a process approach which goes beyond the company’s functions since it works transversally within the firm. Such a mechanism will be successful only if there is general awareness and understanding of the central role intangible resources (including sustainability aspects) play within a highly competitive and technological sector.

Figure 20.3 The delineated process

p.325

The pilot project the research group was responsible for concerns the implementation of the outlined model for a series of specific initiatives that the company planned for 2014 in line with sustainable management, namely: Life Cycle Assessment (Eco Design), Eco Recycling, Age Diversity Management, Green Communication, Green Procurement, and Charity and Welfare.

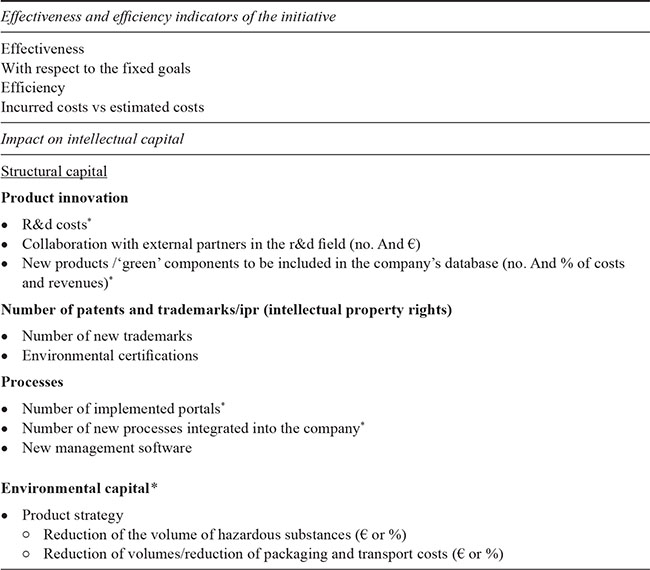

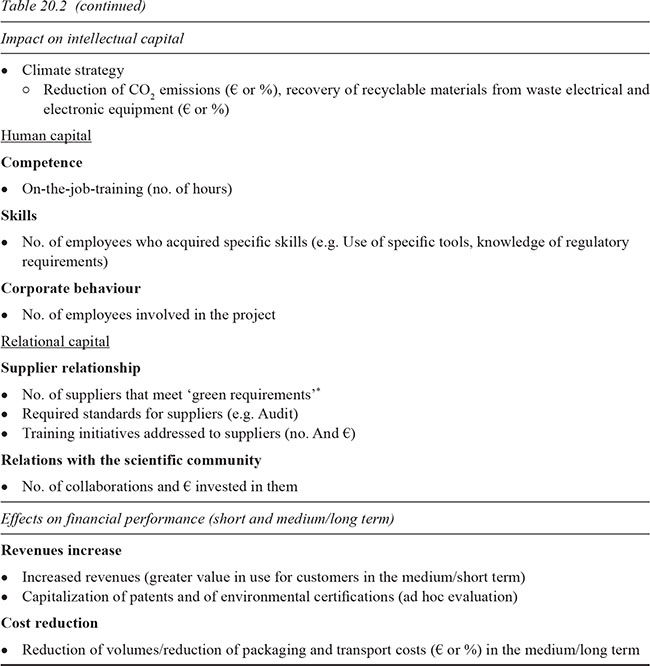

The IC measurement model implies the identification and use of a tailor-made measurement system. In order to monitor each single initiative, a set of performance indicators is available:

• effectiveness indicators (to monitor if the organization has reached the planned goals);

• efficiency indicators (to monitor the related costs);

• indicators to measure the impact the initiative has on the company’s IC; and

• indicators to measure financial performance.

Indicators are defined by personnel in charge of specific initiatives with the support of experts on intangible management control, whose task is to gather data for management reporting.

To give an example, we concentrate only on the first of the aforementioned initiatives, that is, Life Cycle Assessment (Eco Design) – LCA. The aim of LCA is to carry out a feasibility study (concerning methods, timing, and costs) on the implementation of an environmental impact assessment with respect to the company’s whole life production process. Possible indicators – useful for the Life Cycle Assessment (Eco Design) project – are listed in Table 20.2.

Table 20.2 Indicators for life cycle assessment (eco design) initiative

p.326

* Key performance indicators relevant for the Dow Jones Sustainability Index (DJSI) questionnaire

Discussion and conclusions

The assessment process to which companies are subject for inclusion in sustainability indices is built on a wide array of financially relevant sustainability criteria concurrently covering the economic, environmental, and social dimensions. Within this context, intangible resources and capabilities are broadly recognized as the most influential sources of value creation and competitive advantage. Therefore, it seems reasonable to posit that the evaluation of firms’ IC represents a promising starting point for the incorporation of environmental and social aspects into the general management system.

p.327

We argue that intangibles can be regarded as the mediating variables between sustainability management and corporate financial performance. Accordingly, a management control system that enhances sustainability performance by measuring and managing the firm’s IC – such as skills and competencies, knowledge and innovation, values, legitimacy, trust and reputation – has been depicted. More specifically, we posit that accounting for environmentally and socially responsible activities through the effect of mediating contingent variables (i.e. firm-specific intangibles) allows managers to be aware of what drivers of performance can lead to both revenue and cost-related outcomes.

The top management’s willingness to integrate IC and corporate social responsibility perspectives into the company’s management system and communication process arose following changes that occurred in the management team and the inclusion of the company in the DJSI. This was the first step, which motivated sustainability performance measurement; consequently, the development and implementation of sustainability initiatives required the support of appropriate mechanisms such as management accounting and control. Indeed, these events have contributed to the topic of sustainability becoming a primary strategic objective. To this end, the company’s CEO has demonstrated his interest in building an organizational unit entirely devoted to promoting sustainability. Commitment to sustainability is communicated both externally (through formal claims) and internally (by progressively including sustainability principles into organizational culture).

Thanks to our methodological approach – action research – we have an inside perspective on the process that involved the managers of the analysed company in planning environmentally and socially responsible activities for 2014. Our investigation aims to demonstrate that measurement is not the main goal of managerial accounting, but is rather a means to manage and create value (Catasús et al., 2007). As Mouritsen and Larsen (2005) point out, there is an additional management control agenda where information is an input to management activities. This means, to be able to understand the relationships existing between measurement and operational activities on the one hand, and strategies and context on the other. We find that it is extremely important for managers to be aware of the mechanism that allows environmental and social initiatives to increase specific intangibles (operational-side), and which intangibles need strengthening in order to increase the competitive advantage of a firm (strategy-side) within a particular context. Yet, we deem that the extent of such a change and the level of a real strategic renewal depends on an organization’s commitment to sustainability and the role ascribed to, and actual use of, management control systems (Gond et al., 2012).

To date, the main critical factor arising from the intervention plan is the accurate identification of the actors involved in the reporting process. The process mentioned earlier provides a comprehensive view of IC practices within the company; nevertheless, in order to make it work, the cooperation of all owners of the information is required. Retrieving data involves identifying such individuals, which is not always easy in a big business reality; it also implies interacting with the various parties to obtain all contributions. What is also important is the way in which managerial reporting is related to the reward system. This is not straightforward, since the management control system is still at an experimental stage and not yet widely accepted in the business management system.

To overcome these obstacles that might impede the implementation of IC management procedures within the firm, we suggest pilot projects are a good starting point so that emerging problems and opportunities can be dealt with as they arise by personnel involved in day-to-day activities. The chance that a new reporting system is effective relies also on its ‘value in use’ as perceived by the ‘owners’ of the information. Therefore, the study represents a preliminary approach to understanding whether and to what extent a management control system might foster sustainability performance, thus enabling companies to meet the stringent criteria required for inclusion in the DJSI.

p.328

Since sustainability management is as yet in its infancy, its integration poses significant organizational challenges. The management control system proposed in this chapter, which to our knowledge has not been addressed in any previous publication, offers a framework for systematically incorporating sustainability thinking into corporate practice.

References

Arjaliès, D. L. and Mundy, J. (2013), “The use of management control systems to manage CSR strategy: A levers of control perspective”, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 284–300.

Bebbington, J. and Gray, R. H. (2001), “An account of sustainability: Failure, success and a reconceptualization”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 12, No. 5, pp. 557–587.

Berthelot, S., Coulmont, M., and V. Serret (2012), “Do investors value sustainability reports? A Canadian study”, Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 355–363.

Boiral, O. (2013), “Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 26, No. 7, pp. 1036–1071.

Bontis, N. (1998), “Intellectual capital: An exploratory study that develops measures and models”, Management Decision, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 63–76.

Catasús, B., Ersson, S., Gröjer, J., and Yang Wallentin, F. (2007), “What gets measured gets… on indicating, mobilizing and acting”, Accounting, Auditing and Accountability Journal, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp. 505–521.

Cerin, P. and Dobers, P. (2001), “What does the performance of the Dow Jones Sustainability Group Index tell us?”, Eco-Management and Auditing, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 123–133.

Chatterji, A. and Levine, D. (2006), “Breaking down the wall of codes: Evaluating nonfinancial performance measurement”, California Management Review, Vol. 48, No. 2, pp. 29–51.

Chiucchi, M.S. and Dumay, J. (2015), “Unlocking intellectual capital”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 305–330.

Coghlan, D. and Brannick, T. (2010), Doing Action Research in Your Own Organisation, Sage, London.

Demartini, P. and Paoloni, P. (2013), “Implementing an intellectual capital framework in practice”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No.1, pp. 69–83.

Demartini, P., Paoloni, M., and Paoloni, P. (2015), “Sustainability and intangibles: Evidence of integrated thinking”, Journal of International Business and Economics, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 107–122.

Demartini, P., Paoloni, M., Paoloni, P., and Bernardi, C. (2014), “Managerial integrated reporting: Evidence from practice”, Management Control, No. 3, pp. 37–58.

Dias-Sardinha, I. and Reijnders, L. (2005), “Evaluating environmental and social performance of large portuguese companies: A balanced scorecard approach”, Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 73–91.

Dumay, J. (2010), “A critical reflective discourse of an interventionist research project”, Qualitative Research in Accounting and Management, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 46–70.

Dumay, J. (2012), “Grand theories as barriers to using IC concepts”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 4–15.

Dumay, J. (2013), “The third stage of IC: Towards a new IC future and beyond”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 5–9.

Dumay, J. (2016), “A critical reflection on the future of intellectual capital: From reporting to disclosure”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 1, 168–184.

Dumay, J. and Baard, V. (2017), “An introduction to interventionist research in accounting”, in Hoque, Z., Parker, L. D., Covaleski M., and Haynes, K. (Eds), The Routledge Companion to Qualitative Accounting Research Methods, Routledge, Oxford, UK.

Dumay, J. and Garanina, T. (2013), “Intellectual capital research: A critical examination of the third stage”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 10–25.

Dumay, J. and Roslender, R. (2013), “Utilising narrative to improve the relevance of intellectual capital”, Journal of Accounting and Organizational Change, Vol. 9, No. 3, pp. 248–279.

p.329

Dumay, J., Bernardi, C., Guthrie, J., and Demartini, P. (2016), “Integrated reporting: A structured literature review”, Accounting Forum, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 166–185.

Dumay, J., Guthrie, J., and Rooney, J. (2017), “The critical path of intellectual capital”, in Guthrie, J., Dumay, J., Ricceri, F., and Nielsen, C., (Eds), The Routledge Companion to Intellectual Capital, Routledge, London, pp. 21–39.

Edvinsson, L. and M. Malone (1997), Intellectual Capital: Realizing your Company’s True Value by Finding its Hidden Brainpower, Harper Business, New York.

Ferreira, A., Moulang, C., and Hendro, B. (2010), “Environmental management accounting and innovation: An exploratory analysis”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 23, No. 7, pp. 920–948.

Ferrero, I., Fernández, M. Á., and Muñoz, M. J. (2016), “The effect of environmental, social and governance consistency on economic results”, Sustainability, Vol. 8, p. 1005–1021.

Figge, F., Hahn, T., Schaltegger, S., and Wagner, M. (2002), “The sustainability balanced scorecard. linking sustainability management to business strategy”, Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 11, No. 5, pp. 269–284.

Fowler, S. and Hope, C. (2007), “A critical review of sustainable business indices and their impact”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 76, No. 3, pp. 243–252.

Gond, J. P., Grubnic, S., Herzig, C., and Moon, J. (2012), “Configuring management control systems: Theorizing the integration of strategy and sustainability”, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 205–223.

Gray, R. H. (2006), “Social, environmental and sustainability reporting and organisational value creation? Whose value? Whose creation?” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 793–819.

Gray, R. H. (2010), “Is accounting for sustainability actually accounting for sustainability... and how would we know? An exploration of narratives of organisations and the planet”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 47–62.

Gray, R. H. and Milne, M. (2002), “Sustainability reporting: Who”s kidding whom?” Chartered Accountants Journal of New Zealand, Vol. 81, No. 6, pp. 66–70.

Guthrie, J. (2001), “The management, measurement and the reporting of intellectual capital”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 27–41.

Guthrie, J., Cuganesan, S., and Ward, L. (2008), “Industry specific environmental and social reporting: The Australian Food and Beverage Industry”, Accounting Forum, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 1–15.

Guthrie, J., Petty, R., and Johanson, U. (2001), “Sunrise in the knowledge economy: Managing, measuring and reporting intellectual capital”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 365–384.

Guthrie, J., Ricceri, F., and Dumay, J. (2012), “Reflections and projections: A decade of intellectual capital accounting research”, The British Accounting Review, Vol. 44, No.2, pp. 68–82.

Hawn, O., Chatterji, A., and Mitchell, W. (2011), “Two coins in one purse? How market legitimacy affects the financial impact of changes in social legitimacy: Addition and deletion by the Dow Jones Sustainability Index”, Working Paper, Duke University, NC.

Henri, J. F. and Journeault, M. (2010), “Eco-control: The influence of management control systems on environmental and organizational performance”, Accounting, Organizations and Society, Vol. 35, No. 1, pp. 63–80.

Hubbard, G. (2009), “Measuring organizational performance: Beyond the triple bottom line”, Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 177–191.

Jönsson, S. and Lukka, K. (2005), Doing Interventionist Research in Management Accounting, Gothenburg Research Institute, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Kaplan, R. and Norton, D. (1992), “The balanced scorecard: Measures that drive performance”, Harvard Business Review, Jan-Feb, pp. 71–79.

Knoepfel, I. (2001), “Dow Jones Sustainability Group Index: A global benchmark for corporate sustainability”, Corporate Environmental Strategy, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 6–15.

Kolk, A. (2004), “A decade of sustainability reporting: Developments and significance”, International Journal of Environment and Sustainable Development, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 51–64.

Kolk, A. (2008), “Sustainability, accountability and corporate governance: Exploring multinationals’ reporting practices”, Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 1–15.

p.330

Lin, C. S., Chang, R. Y., and Dang, V. T. (2015), “An integrated model to explain how corporate social responsibility affects corporate financial performance”, Sustainability, Vol. 7, No. 7, pp. 8292–8311.

Lòpez, M. V., Garcia, A., and Rodriguez, L. (2007), “Sustainable development and corporate performance: A study based on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 75, No. 3, pp. 285–300.

Lynch, R. L. and Cross, K. F. (1991), Measure Up: The Essential Guide to Measuring Business Performance. Mandarin, London.

Magness, V. (2010), “Environmental disclosure in the mining industry: A signaling paradox?” in Freedman, M. and Jaggi, B. (Eds), Sustainability, Environmental Performance and Disclosures, Advances in Environmental Accounting and Management, Vol. 4, pp. 55–81, Emerald Group Publishing Limited (UK).

Marr, B., Gray, D., and Schiuma, G. (2004b), “Measuring intellectual capital: What, why, and how”, in Bourne, M. (Ed.), Handbook of Performance Measurement, Gee Publishing, London.

Marr, B., Schiuma, G., and Neely, A. (2004a), “The dynamics of value creation: Mapping your intellectual performance drivers”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 312–325.

Montemari, M., and Nielsen, C. (2013), “The role of causal maps in intellectual capital measurement and management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 522–546.

Mouritsen, J. (2006), “Problematising intellectual capital research: Ostensive versus performative IC”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 19, No. 6, pp. 820–841.

Mouritsen, J. and Larsen, H. T. (2005), “The 2nd wave of knowledge management: The management control of knowledge resources through intellectual capital information”, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 371–394.

Neely, A., Adams, C., and Kennerley, M. (2002), The Performance Prism: The Scorecard for Measuring and Managing Business Success, Prentice Hall, London.

Perego, P. and Hartmann, F. (2009), “Aligning performance measurement systems with strategy: The case of environmental strategy”, Abacus, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 397–428.

Perez, E. A., Correa Ruiz, C., and Carrasco Fenech, F. (2007), “Environmental management systems as an embedding mechanism: A research note”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 403–422.

Perrini, F., Russo, A., Tencati, A., and Vurro, C. (2011), “Deconstructing the relationship between corporate social and financial performance”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 102, Issue 1 Supplement, pp. 59–76.

Petty, R. and Guthrie, J. (2000), “Intellectual capital literature review: Measurement, reporting and management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 155–176.

Reason, P. and Bradbury, H. (2006), Handbook of Action Research: The Concise Paperback Edition, Sage, London.

Riccaboni, A. and Leone, E. L. (2010), “Implementing strategies through management control systems: The case of sustainability”, International Journal of Productivity and Performance Management, Vol. 59, No. 2, pp. 130–144.

Ricceri, F. (2008), Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Management: Strategic Management of Knowledge Resources. Routledge, London.

RobecoSAM, (2013), Measuring intangibles: RobecoSAM’s corporate sustainability assessment methodology, available at: www.sustainability-indices.com (accessed May 2014).

Robinson, M., Kleffner, A., and Bertels, S. (2011), “Signaling sustainability leadership: Empirical evidence of the value of DJSI membership”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 101, No. 3, pp. 493–505.

Roos, G. and Roos, J. (1997), “Measuring your company”s intellectual performance”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 413–426.

Roos, J., Roos, G., Dragonetti, N., and Edvinsson, L. (1997), Intellectual Capital: Navigating in the New Business Landscape. Macmillan, London.

Saint-Onge, H. (1996), “Tacit knowledge the key to the strategic alignment of intellectual capital”, Planning Review, Vol. 24, No. 2, pp. 10–16.

Schaltegger, S. (2011), “Sustainability as a driver for corporate economic success: Consequences for the development of sustainability management control”, Society and Economy, Vol. 33, No. 1, pp. 15–28.

Schaltegger, S. and Wagner, M. (2006), “Integrative management of sustainability performance, measurement and reporting”, International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 1–19.

p.331

Schiuma, G., Lerro, A., and Sanitate, D. (2008), “Intellectual capital dimensions of Ducati”s turnaround: Exploring knowledge assets grounding a change management program”, International Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 161–193.

Searcy, C. (2012), “Corporate sustsainability performance measurement systems: A review and research agenda”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 107, No. 3, pp. 239–253.

Searcy, C. and Elkhawas, D. (2012), “Corporate sustainability ratings: An investigation into how corporations use the Dow Jones Sustainability Index”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 35, pp. 79–92.

Stewart, T. (1997), Intellectual Capital. The New Wealth of Organisations, Doubleday, New York.

Subramaniam, M. and Youndt. M. A. (2005), “The influence of intellectual capital on the types of innovative capabilities”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 48, No.3, pp. 450–463.

Surroca, J., Tribó, J. A., and Waddock, S. (2010), “Corporate responsibility and financial performance: The role of intangible resources”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 31, No. 5, pp. 463–490.

Sveiby, K. E. (1997), The New Organisational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Knowledge-Based Assets, Berrett-Koehler, San Franciso, CA.

Zakery, A., Afrazeh, A., and Dumay, J. (2017), “Analysing and improving the strategic alignment of firms’ resource dynamics”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol.18, No. 1, pp. 217–240.