Table 21.1 Reasons for analysing and measuring IC

p.332

LEVERS AND BARRIERS TO THE IMPLEMENTATION OF INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL REPORTS

Maria Serena Chiucchi, Marco Giuliani, and Stefano Marasca

Introduction

Intellectual capital (IC) has been debated for decades. The first of three stages of IC research was focused on raising awareness of IC, and on new methods for measuring it. The second stage was aimed at building theory while the third stage has aimed to investigate IC from a critical and performative perspective, by challenging taken-for-granted assumptions (Dumay, 2013; Guthrie, et al., 2012). By analysing the evolution of the IC discourse, we can see that both scholars and practitioners have proposed a plethora of IC concepts (Chaminade and Roberts, 2003; Meritum Project, 2002; Mouritsen, et al., 2001; Stewart, 1997) and reporting frameworks (Andriessen, 2004; Sveiby, 2010) none of which can be considered as generally accepted, implying that individual organizations have defined their own specific IC reporting agenda according to their particular purposes (Abeysekera, 2008, p. 39; Sveiby, 2010).

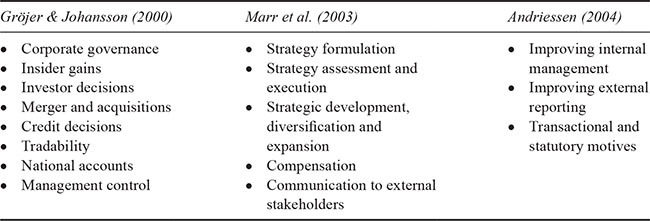

There are two different perspectives on IC (Brännström et al., 2009; Brännström and Giuliani, 2009; Roslender and Fincham, 2001, 2004). The first is focused on IC management and the second on IC disclosure. In the first, the underlying idea is that measuring and reporting IC enables the firm to manage its resources and activities and to deliver sustainable competitive advantage. In the second, the disclosure of IC can lead to more efficient capital markets and company valuations. These two perspectives are the foundation for different approaches to reporting IC (Andriessen, 2004; Gröjer and Johansson, 2000; Marr, et al., 2003). Table 21.1 summarizes the main reasons for analysing and measuring IC as suggested by the extant literature. These reasons can coexist and change over time according to internal or external contexts (Giuliani, 2009, 2015a).

p.333

Table 21.1 Reasons for analysing and measuring IC

Despite the various benefits attributed ex ante, the implementation of IC reporting frameworks is not widespread in practice (Dumay, 2009, 2012; Lönnqvist et al., 2009; Chiucchi, 2013a). More specifically, early adopters, such as Skandia, have abandoned IC reporting and a recent study of companies that participated in the Danish project has shown that few of them continued to report IC after the end of the project (Schaper, 2016). This makes urgent a reflection on how measuring IC can help to realize the benefits attributed to it and an examination of what are the levers and barriers that can influence the successful implementation of an IC report and its long-term fate (Catasús et al., 2007; Catasús and Gröjer, 2006; Chiucchi, 2013b; Chiucchi and Montemari, 2016; Dumay, 2012; Giuliani et al., 2016; Lönnqvist et al., 2009).

Several studies have highlighted some of the levers and barriers to the adoption of IC reports. The barriers include:

• the existence of grand theories, such as that which represents IC as the difference between market and book value and that which maintains that IC disclosure leads to efficiency in capital markets, which can be misleading (Dumay, 2012);

• the complexity of the data collection and calculation processes (Catasús and Gröjer, 2006; Demartini and Paoloni, 2013);

• the fact that IC indicators may be perceived as ‘provocative’, as they give visibility to local practices (Vaivio, 2004), or ‘rapidly obsolete’, because of the changes in the competitive environment and/or users’ needs (Chiucchi, 2013b; Dumay and Rooney, 2011), or as ‘fragile’, due to their lack of completeness and isomorphism (Chiucchi and Montemari, 2016);

• specific qualities of IC measurements (not self-evident, ambiguity, not fully comparable, etc.) (De Santis and Giuliani, 2013; Giuliani, 2014; Giuliani et al., 2016; Mårtensson, 2009);

• the fact that IC scores may not confirm the users’ perceptions or expectations (Chiucchi and Montemari, 2016);

• the ‘lock in’ or ‘accountingization’ phenomenon (Chiucchi and Dumay, 2015; Dumay, 2009; Habersam et al., 2013) that occurs when IC measurement dominates IC management and consequently the production of numbers is not followed by their use.

Recently, Schaper (2016, p. 66–68) investigated why companies that implemented the Danish Intellectual Capital Statements (Mouritsen et al., 2003) have abandoned this practice. The author highlights the following principal factors: no purpose or value perceived; organizational change; other priorities; difficulties in implementation; IC statements managed merely as a project; low interest from management; abandonment by key employees; and no completion of the first project.

p.334

Studies have shown that levers to the implementation and diffusion of IC reporting frameworks can be attributed to:

• the ambiguity of the IC concept, which makes it more likely that managers will make sense of IC and engage with it by applying it to corporate concerns so that IC can be enacted and used as a solution to issues (Cuganesan et al., 2007; Dumay, 2008; Dumay and Rooney, 2016);

• the involvement of managers in designing IC frameworks so that they engage with IC (Chiucchi, 2013b; Chiucchi and Dumay, 2015);

• the creation of tailor made solutions and the rejection of the one-size-fits all approach (Dumay, 2009);

• the ‘dramatization’ of IC indicators (Catasús and Gröjer, 2006);

• the visualization of the value creation and destruction processes (Cuganesan, 2005; Cuganesan and Dumay, 2009; Giuliani, 2013, 2015b);

• the linkages between numbers and specific organizational challenges (Dumay and Guthrie, 2007).

Levers and barriers can also relate to the actors involved in the process of production and use of IC measurements and to their engagement (Dumay and Rooney, 2011). In particular, two types of actors seem to be particularly important, as they determine the design, implementation, and development trajectories of IC projects and, consequently, can act as levers or as barriers (Chaminade and Roberts, 2003; Chiucchi, 2013a, 2013b). These are the project sponsor and the project leader. The project sponsor can be defined as the person who promotes the relevance of IC within the organization, supports the development of the project, and gives legitimation to the IC project. The project leader is the person that develops the IC project in practice, that is, the person actually involved in the design and implementation of the IC reports.

The aim of this chapter is to analyse the levers and barriers to the implementation of IC reports from a longitudinal perspective, thus contributing to the third stage of IC research.

Research method

In order to gather insights into levers and barriers to the implementation of IC reports, we conducted a field study, which is “a research design that embraces a relatively small number of companies, as opposed to a wide-ranging survey or intensive case enquiries in two or three companies” (Roslender and Hart, 2003, p. 262). This method is considered suitable to explore “complex phenomena in a confined domain” (Lillis and Mundy, 2005, p. 131).

We focused on Italian firms because “Italy has become the new, hot bed of IC research, especially aimed at working side by side with managers inside organizations in developing IC practices” (Dumay, 2013, p. 6). Furthermore, different from other countries, such as for instance Denmark (Schaper, 2016), where national projects on measuring and reporting IC have been launched, there have been no national or large-scale projects in Italy and companies began to measure IC on their own initiative, in different points in time, with different aims, and adopting different frameworks.

p.335

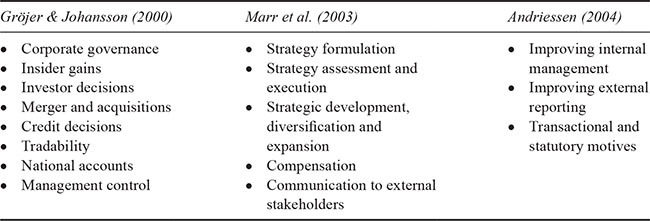

Table 21.2 Interview’s main themes

Our sample is composed of companies that prepared at least one IC report for disclosure and/or managerial aims. Therefore we included in our research only companies that reported IC according to the system of intangible resources categorized as human, organizational, and relational capital (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Sveiby, 1997). This means that we excluded companies that report only specific IC resources, such as human capital or relational capital, for instance.

Considering the ad hoc implementation of IC reporting practices, the name and number of companies that have ever produced an IC report in Italy is unknown. Therefore, in order to identify them, we adopted a step-by-step process. First, a review of national and international publications within the IC field was carried out using SCOPUS, Google books, and Google libri (Italian version of Google books). Second, we searched Google to collect data about companies not mentioned in publications but which have declared that they report or have reported IC. Third, in order to integrate the results of steps one and two, several people familiar with the Italian IC field were interviewed to ensure the list produced after steps one and two was complete and, if not, identify missing firms. The result was a list of 34 companies being identified, representing the majority of Italian firms producing IC reports. Of these, 16 companies agreed to be involved in this research project (hereafter named with letters from ‘A’ to ‘P’).

Semi-structured interviews with preparers were conducted (Kreiner and Mouritsen, 2005; Qu and Dumay, 2011) to determine levers and barriers and also to compare different practical experiences of IC reporting. Semi-structured interviews are well suited for the exploration of the perceptions and opinions of respondents regarding complex and sometimes sensitive issues. In addition, they also allow the interviewer to probe for more information and elicit clarification of answers. A list of questions was submitted to the interviewees beforehand, but we also allowed open discussion to emerge. The interview was piloted in two companies around the themes listed in Table 21.2.

The 16 analysed companies differed in size and mainly belonged to the private sector (69 per cent), with public sector (19 per cent) and non-profit sector (12 per cent) companies also represented in the sample.1

We interviewed those people in the organization who had guided the IC reporting project; in all, we interviewed 18 people. In seven cases, the interviewees were also the projects’ promoters (those who were first interested in IC, promoted, and supported the IC report).

Interviews were conducted during the spring and summer of 2014, lasting from one to two hours each, were all tape-recorded, and then transcribed for analysis. In order to overcome bias, the analysis was carried out through triangulation (Patton, 1990; Yin, 2003); thus, it was designed in such a way that one of the researchers was responsible for data collection, while the others examined the interview material and notes. Post-interview communication with the respondents helped the authors to ensure the accuracy of collected data.

Results

Reasons for introducing an IC report

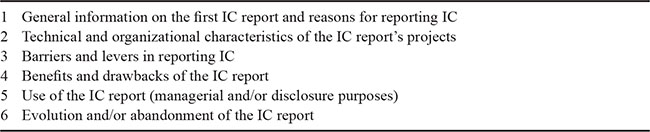

The majority of the companies in our sample declared to have undertaken IC reporting projects both for managerial and disclosure reasons (69 per cent) or exclusively for managerial reasons (31 per cent). None prepared an IC report only for disclosure aims. Among the analysed companies, 13 have continued measuring and reporting IC for some years whereas 3 stopped after the first experience. ‘Meteors’ are therefore of marginal relevance in our sample. The average duration of the experience is 6.38 years with a maximum of 16 to a minimum of 1 year (see Table 21.3).

p.336

Table 21.3 Data overview

All interviewees declared they reported IC for several reasons. Some of the interviewees pointed out that when their projects started there was uncertainty about what an IC report was and which aims an IC report could expect to realize.

At the beginning we had no ideas about this type of projects… (A)

Various interviewees said they had decided to report IC to improve disclosure. Sometimes, interviewees talked in general terms about “communicating company value” (C, N) or about “improving transparency” (B, L). In some cases, the reasons given were more specific and referred to filling the gaps in the typical financial statement with information that could better illustrate company strategy, activities, and characteristics (A, E, J, K, L), and permitted a more complete and realistic picture of the company.

[b]efore transparency became mandatory or a “big issue”, we used to publish on our website our Corporate Social Responsibility report where our stakeholders could understand what we do, our activities, the benefits we generate for them, etc. In 2007 we decided to include in our report also these aspects related to human, relational and organizational capital. (B)

Surely the IC report has information that are [sic] not reported in typical financial statements and that give a better picture of our “non-financial activities”, that is the results achieved and the activities carried out that do not have a financial accounting impact. Thus, this kind of reporting fits much better with an organization like ours … it offers a more appropriate perspective for non-traditional companies like us. (A)

p.337

I have two main reasons. The first reason is the improvement of the information flow towards our stakeholders, establishing a kind of a dialogue, a way of sharing relevant information … The second reason is that by publishing this panel of indicators … by representing our culture and by disclosing our commitment to our stakeholders and the society, it would be difficult to ignore them in case of a change of the management or of the ownership. In this way, we wanted to define our long-term perspective. (E)

We tried to understand what we could do to give to our stakeholders a more complete picture of what we actually do. So, we started thinking how to do it … We noticed that several information [sic] of the IC report were [sic] complementary to the financial ones and they allowed us to show to our stakeholders how and why we spend our money, what we have done for them, etc. They allow [us] to disclose a more reliable and realistic picture of our business. (J)

In some cases, IC reports were produced to improve communication aimed at specific stakeholders. Here the idea was to give emphasis to the role of the company in the value chain of customers or suppliers (G), to show the “real company value” to financial institutions (N), or to produce information that could be useful in mergers and acquisitions and which went beyond financial numbers (L).

We have tried to make the prospective partner understand who we are and what we expect from him … and that we are a delicate organism and there are some elements that have to be considered when merging together: our employees, the way we manage them, the way knowledge is disseminated, the way we are used to doing our job. All in all, the IC statement should help our ‘Chieftain’ make the colonizers understand that we are not exactly cavemen. (L)

In other cases, there was also the will to show that the company was innovative (K, L).

[w]e had, to some extent, satisfaction by showing that we were interested in these issues and that were doing things that only some big firms were doing. (K)

In other cases, the IC report was produced to enrich existing voluntary disclosure, made through Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) reports (Bilancio Sociale), with information on intangibles and to give emphasis to some labour issues. (G)

As far as managerial aims are concerned, projects were aimed at promoting a better understanding of the company and of its performance by:

• filling the gaps of financial information (C, D, K, N);

• showing the company’s ability to implement strategy and accomplish projects (E);

• providing information on key success factors; and

• depicting how the company used resources and competences to build relationships with suppliers and to develop processes and technologies (P).

In some cases, the aims were also related to the project leader’s aim to legitimize his or her actions and decisions. This was done by providing evidence to the rest of the company or to the board of directors/owner that company value was higher than book value (H) or showing the activities done over the years by a specific department (L).

I need to give a sort of authority to the new Department I am heading, which I think stems from a great intuition from an organizational point of view: put together all the non-financial activities, all the support activities. It is crucial to show that this new Department has its usefulness, that it uses scientific tools and that it promotes coordinated actions within the company. This project is useful also to me (emphasis added) (L).

p.338

In other instances, the aims for reporting IC were related to human resources and include gaining a more in-depth understanding of the personnel, to producing information to support decisions related to them. The IC report was produced to understand people and their competencies (D, I) and the risks associated with their management (E), and to acquire knowledge on workplace relationships to support and guide personnel policies (L). At the same time, the IC report was also aimed at stimulating certain behaviours and actions related to personnel. Companies pointed out that by reporting IC they aimed to improve organizational consciousness and integration among people (B, G, J) and alignment to company values (J). IC reporting was considered useful also to satisfy top management’s desire to undertake stimulating and innovative projects (I, M).

Finally, other reasons reported related to specific objectives such as supporting change management processes (A) or improving effectiveness and efficiency (O).

The frameworks adopted to report IC

As there has not been any large-scale IC reporting projects in Italy and, consequently, companies have decided to implement them on an ad hoc basis, in different time-points and under the guidance of different consultants or researchers, the frameworks used to report IC differed from respondent to respondent.

In 13 cases, IC reports were standalone documents while in the other 3 cases they were part of CSR reports where there was a specific section referring to IC. In one case, after a few years, the IC report ceased to be a standalone document and was integrated with the company’s quality report.

When IC reports were standalone documents, they were predominantly inspired by famous and widely used frameworks, mainly the Intangible Asset Monitor (Sveiby, 1997) and the Meritum guidelines (Meritum Project, 2002).

While for all companies the experience of reporting IC started with the production of an IC report, it did not necessarily end in the same form. Among the companies that stopped producing an IC report, four continued measuring specific dimensions of IC using only some parts of the initial IC report that became part of corporate and/or departmental control systems.

The practice of reporting IC as a part of the CSR report deserves some further discussion. In the Italian context, sustainability and social and environmental reports have a long history and several initiatives on CSR have taken place, both at private and public level (Borga et al., 2009; Hinna, 2002). More specifically, the Italian “Gruppo di Studio per il Bilancio Sociale” (Italian Group for Studies on Social Reporting) has published guidelines for preparing social reports, the so-called ‘GBS model’, in 2001, with the latest version released in 2013 (GBS, 2013). In 2003, the Italian Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs launched the CSR-SC Project, presented as “the Italian contribution towards the promotional campaign of CSR throughout Europe” (Baldarelli, 2007, p. 8), aimed at spreading CSR culture among companies and public institutions and guaranteeing citizens that CSR communication is not misleading. Within this project a Social Statement is promoted that firms can adopt on a voluntary basis and which aims to guide the reporting of CSR performance (Baldarelli, 2007).

p.339

Although IC reports and CSR reports have been developed as independent models of reporting, research suggests some similarities. Cordazzo (2005) analysed 83 environmental and social reports of Italian companies and found similarities between these reports and IC reports. The author concluded that environmental and social reports could support the development of IC reporting in Italy and also that “the IC report could be a useful tool for generalizing these two sets of accounts by interpreting (and visualizing) the ‘society’ and the ‘environment’ as part of the new value-drivers of a company” (p. 459). Del Bello (2006) analysed a local government sustainability report, suggesting two possible integration processes between this document and the IC report: a weak integration process, leading to a set of common indicators, and a strong integration process, which could generate a new form of single reporting. Similarly, Pedrini (2007), by observing that IC and CSR reports have several convergence points (e.g. methodology, issues covered, such as human resources), proposed the reports be integrated into a ‘Global or Holistic Report’, which would show how CSR strategy has been developed, how it influences intangible resources, and the company’s commitment to orient CSR strategy to maximize the firm’s value. More recently, Cinquini et al. (2012) investigated the content, frequency, and quality of IC disclosure and the changes that took place over two years (2005 and 2006) in 37 sustainability reports published by Italian listed companies. The authors, by showing that sustainability reports present a range of information on IC, confirmed the findings of studies that have demonstrated that sustainability reports could be useful for providing some information on IC. Schaper et al. (2017), by examining the Danish context, identified a trend towards more integrated forms of reporting, motivated in part by the need to reduce reporting overload. To conclude, all these studies, while recognizing that IC reports and CSR reports have different objectives and stakeholders, highlight that a convergence between the two is possible and even desirable.

Levers to the implementation of IC reports

In the interviews, we explicitly formulated questions regarding the perceived conditions that can favour the implementation of IC reports, that is, IC reporting levers. From the interviews it emerged that levers can be related both to technical (e.g. frameworks, indicators, etc.) and organizational (e.g. actors involved, personnel involvement, commitment, etc.) aspects of IC projects.

In term of technical aspects, the main levers can be identified as follows:

• the existence of a quality system, of a well-developed management accounting system, and of existing databases as well as of a business intelligence system;

• the possibility to concentrate and directly control the production of indicators in one department;

• the managers’ familiarity with using non-financial indicators;

• the strong connection between the IC report initiative and company strategy.

Size is considered a lever, as smaller companies are better able to communicate with staff and therefore can more easily explain the meaning of the project, obtain data, and secure staff involvement.

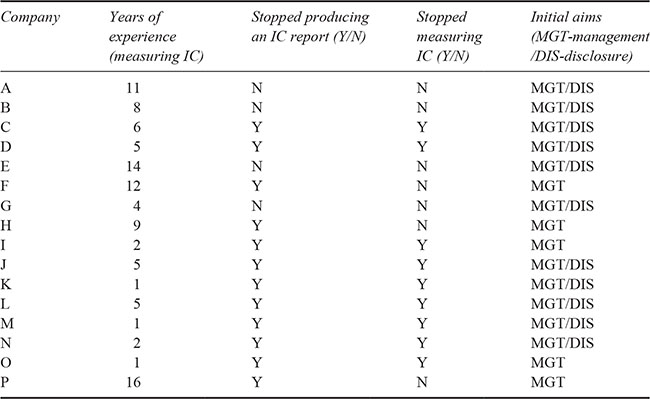

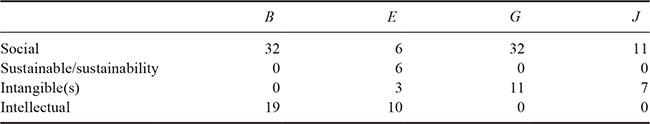

Four of the analysed companies reported IC as a separate section of their CSR report and one as a part of its quality report. These companies are among those still reporting IC, suggesting that combining the IC report and other voluntary reports seems to be successful. Nevertheless, in those cases in which the IC report is a separate section of the CSR report, the experience of measuring IC seems to merge with that of CSR reporting. Even if we asked questions specifically referring to the IC project and the IC report, interviewees frequently answered referring to the social report and to social/sustainability accounting. In support of this, we counted the times the interviewees used the words ‘social’, ‘sustainable/sustainability’, ‘intangible(s)’, and ‘intellectual capital’ (see Table 21.4).

p.340

Table 21.4 Use of terms during interviews

All but one company used the words ‘social’ and ‘sustainable/sustainability’ more so than ‘intangibles’ and or ‘intellectual capital’; in company E, their use is almost equal.

With regard to organizational aspects, the interview data suggests that three types of actors emerge as relevant: project leaders, project sponsors, and external partners (consultants and university researchers). These have a fundamental role in undertaking these projects, in determining their aims, in carrying out the projects, and in continuing and/or in abandoning them. For instance, in those cases in which the project leader was the CFO/controller the IC report was used for management aims, and even if some of the companies stopped producing an IC report, specific parts of it were then included in departmental or corporate management accounting systems. Therefore, specific dimensions of IC continued to be analysed in different forms and with different tools. In this sense, the competences of the project leader influenced the development trajectories of the IC projects.

In general, the sponsorship of the board of directors and/or of the entrepreneur has been identified as a key lever by all interviewees and it appears that all projects could benefit from this sponsorship. Similarly, specific managers’ sponsorship, for example, the heads of human resources and/or marketing departments, has been identified as a lever.

External partners appear to be particularly relevant: almost all companies (15) undertook the IC reporting project under the guidance of consultants and/or university researchers. However, in one company, the president had the initiative to undertake the project and guided it because he had already participated in the preparation of an IC report in the company in which he was previously working. External partners played different roles; as ‘coach’ they guided and cooperated actively in measuring and reporting IC during the first years. In those cases in which companies became autonomous in producing IC reports, external partners continued to be consulted from time to time to discuss the evolution of the IC reports. The relevance of the consultants in some cases went far beyond this and they not only cooperated and/or guided the project but were referred to as the “real promoters” of the projects. Some interviewees admitted that before the project began they did not even know what IC was. Therefore, they trusted the consultants and the idea of IC; two respondents referred to one of the consultants as a “guru”.

Barriers to the implementation of IC reports

We also specifically asked about perceived barriers to reporting IC. In terms of technical aspects, interviewees stressed the following:

p.341

• producing an IC report is a time-consuming activity as it requires a specific and complex data collection and data analysis process;

• the need to devote personnel to the project (and the expenses connected to this);

• the need for high commitment and cooperation by those who collect and process information;

• the need to obtain the cooperation of other departments for the production of indicators;

• the difficulties in understanding the IC frameworks, in selecting the ‘right’ IC indicators, in understanding and ‘trusting’ the IC indicators, and in linking the IC performance with financial performance.

Some of these technical barriers relate to organizational aspects: in several cases, the design and implementation phases seem to be predominantly circumscribed to the project leader, to his/her department, and to the consulting companies. Company managers were rarely involved as permanent members of the project teams (only in 4 of 16 cases) and their participation ranged from providing the necessary information to designing the system, to producing the data needed for calculating indicators. Sometimes, they did not participate at all. It is worth noting that managers’ involvement in the design and implementation processes was not identified by most interviewees as either a lever (if low) or as a barrier (if high).

The role played by the sponsor, leader, and external partners can also be perceived as a double-edged sword. In fact, if it is true that these actors can contribute to the success of the IC project, it is also true that a change in the role of one of these key actors likely meant a (negative) change in the fate of the IC reports. If this key figure quit the company or changed his/her priorities, the IC report was abandoned. In one case, the interviewee considered the failure of the consulting company as the reason for abandoning the IC report. Respondents offered different reasons for the abandonment of IC reports, including: restructuring processes; the financial crisis and the related need to cut costs; and the inability of IC reports to fulfil their initial aims.

The specialization of the consultant determined the fate of the IC project. When the consultant was a quality systems consultant, even if the IC report initially was a standalone document, over time it became a section of the quality report. When the consultant had already guided the production of a social report, the IC report was or became a section of the social report. Likewise, when the IC report was proposed by a strategy consultant, the IC project had a strong managerial aim and the IC report usually was used to support managerial actions. Finally, when the consultant changed, the IC project failed.

Discussion and conclusions

By presenting a field study of companies that have adopted IC reports, levers and barriers to IC reporting were identified from an empirical perspective. Our study confirms and supports many of the levers and barriers that have been highlighted in the prior literature. The complexity of the data collection and calculation processes, the ‘provocative’ and ‘fragile’ nature of IC indicators, the lack of correspondence between IC measures’ scores and users’ perceptions and expectations, the absence of linkages between IC indicators and financial performance (thus, the limited knowledge of value creation processes) have all been identified as barriers. Elements that make the collection and calculation processes straightforward have been specifically identified as levers: databases, quality and management accounting systems, and software such as business intelligence. Related to this is also the role of the project leader in controlling the collection and calculation processes.

p.342

However, the intensity of each of these levers and barriers can vary in space and time. In other words, the intensity is not perceived as the same in all companies and it can change over time depending on the technical and organizational specificities of each company (e.g. culture, size, accounting system, etc.).

Two specific aspects need to be detailed further: the role of ambiguity and of grand theories. Regarding ambiguity, consistent with Giuliani (2009), we show that the reasons for deciding to measure and report IC vary. Interviewees referred to them in general terms (e.g. improve communication towards stakeholders, improve company performance) and, sometimes, also in very specific terms (e.g. emphasize labour issues such as the ability to offer job opportunities). The term ‘ambiguity’ recurred frequently during the interviews in relation to how the IC reports and the initial aims of the IC project were perceived. This seems to be reinforced by the fact that some interviewees said that consultants were the “real sponsors” and that they (project leaders and company personnel) did not know at the beginning of the project what IC and an IC report was. IC ambiguity is fundamental to the implementation of IC reporting practices, since it is more likely that managers will make sense of IC and engage with it by applying it to corporate concerns or to the project leader’s or sponsor’s concerns (e.g. give authority to a certain department, emphasize specific labour issues, etc.) (Cuganesan et al., 2007; Dumay, 2008; Dumay and Rooney, 2016). Our data shows how this ambiguity can act as a double-edged sword since some projects were undertaken without understanding what companies could expect from the projects and without general aims. Ambiguity, therefore, can act as a lever or as a barrier depending on how the sensemaking and sensegiving processes (Giuliani, 2016) are carried out by the project leader and by the organization.

In terms of grand theories (Dumay, 2012) to justify the implementation of these reports, the evidence suggests that theories appear to support the initial stage of the process and allow for the natural initial distrust related to a new project and/or to new accounts to be overcome (Catasús, 2008; Gray, et al., 1997). At the same time, when the IC report has been implemented, if the expectation created by grand theories, such as performance or the market value improvement, is not fulfilled, grand theories can become one of the reasons for abandoning the IC reporting project. Therefore, grand theories can act as levers or as barriers depending on the organizational context and experience.

While Giuliani (2009, 2015a) shows that IC reporting methods and tools can change in space and over time, we demonstrate that from a technical perspective, levers and barriers can change in space and over time and due to the technical specifics and dynamics of IC reporting methods and tools. Our study suggests that some aspects, such as ambiguity of aims or indicators and the existence of grand theories, can act both as levers and as barriers depending on aspects of the organization and of the development, over time, of the IC reporting project.

Our study also highlights that in Italy, the IC report experience seems to have been linked to that of CSR reporting. While the prior literature has investigated the content, frequency, and quality of IC disclosure in CSR reports (Cinquini et al., 2012; Oliveira et al., 2010; Pedrini, 2007), here we analyse the relationship between these two reports. Our empirics show that the existence of a CSR report can be a lever both to start and to continue IC reporting. At the same time, our data also show that there is a risk that IC reports are subsumed by CSR reports. Our interviewees frequently confused IC reports and information with CSR reports; while this is not necessarily a barrier to the diffusion of IC reporting practices, it becomes a barrier if IC practices are undertaken to reach objectives that differ from those of the CRS reports. The predominantly disclosure nature of CSR reports can be misleading and represent a barrier when IC reporting practices are undertaken to manage IC.

In relation to organizational levers and barriers, consistent with Chiucchi (2013a, 2013b), our study confirms the roles of project leaders and project sponsors as key in undertaking these projects, in determining their aims, in carrying out the projects, and in continuing and/or in abandoning them. Nevertheless, our study adds to this by showing the relevance of the external partners (consultants and in a few cases university researchers) that seem to be in several cases the deus ex machina of the projects. They have a key role in the sense-making and sense-giving processes (Giuliani, 2016) and their specialization influences the way IC is perceived within the company and the fate of the IC report. External partners transferred to companies their own meaning of IC and the IC report and of what organizations could expect from it. This means that the capabilities of the external partners to give sense to the IC report and to allow the organization to make sense of it is relevant in determining the success or failure of IC projects. At the same time, there is the risk of an excessive ‘personalization’, that is a dependence of the project on the external partner (barrier).

p.343

In our interviews, technical barriers are more stressed by interviewees than organizational barriers. The low participation of managers in the design and implementation phase was not generally (but not ever) perceived as a problem. Frequently, the limited participation of managers was perceived as a problem related to the difficulty of collecting and processing data and rarely as a problem related to the use of IC frameworks and measures. Therefore, the initiatives undertaken to solve these problems were usually (even if not always) aimed at solving technical aspects, with the risk of the organizational aspects being overlooked. In this sense, our study confirms that the ‘accountingization’ phenomenon, which occurs when practitioners (and researchers) focus their attention on fitting a company IC into a measurement framework, instead of focusing on its practices Dumay (2009, pp. 205–6), is a relevant barrier to the use of IC concepts and to the realization of their potential.

Finally, the longitudinal perspective of our analysis allows speculation as to the persistence and status of levers and barriers over time. Barriers can be overcome by adopting specific actions, for example, better communication. Barriers can also be superficially overcome but at the cost of depth, for example, the complexity of data calculation and processing was ‘solved’ by reducing indicators. However, barriers can be ‘latent’ and reappear if, for example, key actors consider them a priority.

These findings have both theoretical and practical significance. This study enriches the IC literature based on a performative approach. The results show what happens after IC concepts, methods, and tools are introduced within an organization. The study contributes to the literature on IC “in practice” (Dumay, 2012, p. 12; Guthrie et al., 2012, p. 79) as the analysis is developed in vivo and not in vitro. Finally, this study offers a longitudinal perspective with reference to organizational and technical levers and barriers.

There are two main potential limitations to the study. First, the results can be affected by the typical limitations of the design adopted for the study, that is, generalization is not possible, and the results may be subject to both interviewee and interviewer bias and interpretation. Nevertheless, considering the exploratory nature of the study, generalization on some aspects is possible. Further, while it was not possible to interview all the companies adopting IC reporting, we believe that we provided enough data to make useful observations.

This study calls for more IC research to be carried out by adopting a performative approach in order to understand in greater depth the technical and organizational dimensions of IC, what they are influenced by, and how they determine the success or failure of an IC project. Moreover, it can be interesting to investigate how companies can face and overcome barriers or use levers in practice. Analysing the Italian context can also open up future research avenues by comparing the research findings to similar studies conducted in other country contexts in order to understand if and how the IC reporting genesis can influence its evolution.

p.344

Note

1 For privacy reasons, we are not allowed to disclose more information than is reported in this chapter (e.g. sector, dimension, etc.) in order to protect the anonymity of the companies.

References

Abeysekera, I. (2008), “Intellectual capital practices of firms and the commodification of labour”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 21, No. 1, pp. 36–48.

Andriessen, D. (2004), Making Sense of Intellectual Capital: Designing a Method for the Valuation of Intangibles, Elsevier Butterworth–Heinemann, Burlington, MA.

Baldarelli, M. G. (2007), “New prospectives in inter-company relations, social responsibility (CSR) and social, ethical and environmental accounting in Italy by way of the government CSR-SC project: Theory and praxis”, Economia Aziendale Online, Vol. 1, pp. 1–26.

Borga, F., Citterio, A., Noci, G., and Pizzurno, E. (2009), “Sustainability report in small enterprises: Case studies in Italian furniture companies”, Business Strategy and the Environment, Vol. 18, No. 3, pp. 162–176.

Brännström, D. and Giuliani, M. (2009), “Accounting for intellectual capital: A comparative analysis”, VINE: The Journal of Information and Knowledge Management Systems, Vol. 39, No. 1, pp. 68–79.

Brännström, D., Catasús, B., Gröjer, J.-E., and Giuliani, M. (2009), “Construction of intellectual capital: The case of purchase analysis”, Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 61–76.

Catasús, B. (2008), “In search of accounting absence”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 19, No. 7, pp. 1004–1019.

Catasús, B. and Gröjer, J.-E. (2006), “Indicators: On visualizing, classifying and dramatizing”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 187–203.

Catasús, B., Errson, S., Gröjer, J.-E., and Wallentin, F. Y. (2007), “What gets measured gets... On indicating, mobilizing and acting”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 20, No. 4, pp. 505–521.

Chaminade, C. and Roberts, H. (2003), “What it means is what it does: A comparative analysis of implementing intellectual capital in Norway and Spain”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 733–751.

Chiucchi, M. S. (2013a), “Intellectual capital accounting in action: Enhancing learning through interventionist research”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 48–68.

Chiucchi, M. S. (2013b), “Measuring and reporting intellectual capital: Lessons learnt from some interventionist research projects”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 395–413.

Chiucchi, M. S. and Dumay, J. (2015), “Unlocking intellectual capital”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 16, No. 2, pp. 305–330.

Chiucchi, M. S. and Montemari, M. (2016), “Investigating the ‘fate’ of intellectual capital indicators: A case study”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 238–254.

Cinquini, L., Passetti, E., Tenucci, A., and Frey, M. (2012), “Analyzing intellectual capital information in sustainability reports: Some empirical evidence”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 13, No. 4, pp. 531–561.

Cordazzo, M. (2005), “IC statement vs environmental and social reports: An empirical analysis of their convergences in the Italian context”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 441–464.

Cuganesan, S. (2005), “Intellectual capital-in-action and value creation. A case study of knowledge transformation in an innovation process”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 357–373.

Cuganesan, S. and Dumay, J. (2009), “Reflecting on the production of intellectual capital visualisations”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 22, No. 8, pp. 1161–1186.

Cuganesan, S., Guthrie, J., and Boedker, C. (2007), How Mutable Discourse Shapes Material Practice: An Accounting of Intellectual Capital, Macquarie Graduate School of Management, Sydney.

Del Bello, A. (2006), “Intangibles and sustainability in local government reports: An analysis into an uneasy relationship”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 4, pp. 440–456.

Demartini, P. and Paoloni, P. (2013), “Implementing an intellectual capital framework in practice”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 69–83.

p.345

De Santis, F. and Giuliani, M. (2013), “A look on the other side: Investigating intellectual liabilities”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 2, pp. 212–226.

Dumay, J. (2008), “Narrative disclosure of intellectual capital: A structurational analysis”, Management Research News, Vol. 31, No. 7, pp. 518–537.

Dumay, J. (2009), “Intellectual capital measurement: A critical approach”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 190–210.

Dumay, J. (2012), “Grand theories as barriers to using IC concepts”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 4–15.

Dumay, J. (2013), “The third stage of IC: Towards a new IC future and beyond”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 5–9.

Dumay, J. and Guthrie, J. (2007), “Disturbance and implementation of IC practice: A public sector organisation perspective”, Journal of Human Resource Costing and Accounting, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 104–121.

Dumay, J. and Rooney, J. (2011), “‘Measuring for managing?’ An IC practice case study”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 12, No. 3, pp. 344–355.

Dumay, J. and Rooney, J. (2016), “Numbers versus narrative: An examination of a controversy”, Financial Accountability & Management, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 202–231.

Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M. S. (1997), Intellectual Capital, Harper Business, New York.

GBS (2013), Gruppo di studio per il bilancio sociale: Il bilancio sociale. Standard. Principi di redazione del bilancio sociale, Giuffrè, Milan, Italy.

Giuliani, M. (2009), “Intellectual capital under the temporal lens”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 10, No. 2, pp. 246–259.

Giuliani, M. (2013), “Not all sunshine and roses: Investigating intellectual liabilities ‘in action’”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 127–144.

Giuliani, M. (2014), “Accounting for intellectual capital: Investigating reliability”, International Journal of Finance and Accounting, Vol. 3, No. 6, pp. 341–348.

Giuliani, M. (2015a), “Intellectual capital dynamics: Seeing them ‘in practice’ through a temporal lens”, Vine, Vol. 45, No. 1, pp. 46–66.

Giuliani, M. (2015b), “Rome wasn’t built in a day… Reflecting on time, intellectual capital and intellectual liabilities”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 2–19.

Giuliani, M. (2016), “Sensemaking, sensegiving and sensebreaking: The case of intellectual capital measurements”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 218–237.

Giuliani, M., Chiucchi, M. S., and Marasca, S. (2016), “A history of intellectual capital measurements: From production to consumption”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 3, pp. 590–606.

Gray, R., Dey, C., Owen, D., Evans, R., and Zadek, S. (1997), “Struggling with the praxis of social accounting: Stakeholders, accountability, audits and procedures”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 10, No. 3, pp. 325–364.

Gröjer, J. E. and Johansson, U. (2000), Accounting for Intangibles at the Accounting Court, available at: www.fek.su.se (accessed 22 December 2007).

Guthrie, J., Ricceri, F., and Dumay, J. (2012), “Reflections and projections: A decade of intellectual capital accounting research”, The British Accounting Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 68–82.

Habersam, M., Piber, M., and Skoog, M. (2013), “Knowledge balance sheets in Austrian universities: The implementation, use, and re-shaping of measurement and management practices”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp. 319–337.

Hinna, L. (2002), Il bilancio sociale, Il sole 24 ore, Milan, Italy.

Kreiner, K. and Mouritsen, J. (2005), “The analytical interview: Relevance beyond reflexivity”, in Tengblad, S., Solli, R., and Czarniawska, B. (Eds), The Art of Science, Liber & Copenhagen Business School Press, Kristianstad, Denmark, SW, pp. 153–176.

Lillis, A. M. and Mundy, J. (2005), “Cross-sectional field studies in management accounting research:Closing the gaps between surveys and case studies”, Journal of Management Accounting Research, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 119–141.

Lönnqvist, A., Kianto, A., and Sillanpää, V. (2009), “Using intellectual capital management for facilitating organizational change”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 559–572.

Marr, B., Gray, D., and Neely, A. (2003), “Why do firms measure their intellectual capital?”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 441–464.

Mårtensson, M. (2009), “Recounting counting and accounting: From political arithmetic to measuring intangibles and back”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 20, No. 7, pp. 835–846.

p.346

Meritum Project (2002), Guidelines for Managing and Reporting on Intangibles (Intellectual Capital Report), European Commission, Madrid.

Mouritsen, J., Bukh, P. N., Flagstad, K., Thorbjørnsen, S., Johansen, M. R., Kotnis, S., Larsen, H. T., Nielsen, C., Kjærgaard, I., Krag, L., Jeppesen, G., Haisler, J., and Stakemann, B. (2003), Intellectual Capital Statements: The New Guideline, Danish Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (DMSTI), Copenhagen.

Mouritsen, J., Larsen, H. T., and Bukh, P. N. D. (2001), “Intellectual capital and the ‘capable firm’: Narrating, visualising and numbering for managing knowledge”, Accounting Organizations and Society, Vol. 26, Nos 7–8, pp. 735–762.

Oliveira, L., Lima Rodrigues, L., and Craig, R. (2010), “Intellectual capital reporting in sustainability reports”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 575–594.

Patton, M. Q. (1990), Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods, Sage, Newbury Park, CA.

Pedrini, M. (2007), “Human capital convergences in intellectual capital and sustainability reports”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 346–366.

Qu, S. Q. and Dumay, J. (2011), “The qualitative research interview”, Qualitative Research in Accounting & Management, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 238–264.

Roslender, R. and Fincham, R. (2001), “Thinking critically about intellectual capital accounting”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 383–398.

Roslender, R. and Fincham, R. (2004), “Intellectual capital accounting in the UK: A field study perspective”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 178–209.

Roslender, R. and Hart, S. J. (2003), “In search of strategic management accounting: Theoretical and field study perspectives”, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 255–279.

Schaper, S. (2016), “Contemplating the usefulness of intellectual capital reporting: Reasons behind the demise of IC disclosures in Denmark”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 52–82.

Schaper, S., Nielsen, C., and Roslender, R. (2017), “Moving from irrelevant intellectual capital (IC) reporting to value-relevant IC disclosures: Key learning points from the Danish experience”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 81–101.

Stewart, T. A. (1997), Intellectual Capital, Bantam Doubleday Dell Publishing Group, New York.

Sveiby, K. E. (1997), The New Organisational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Knowledge-Based Assets, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, CA.

Sveiby, K. E. (2010), “Methods for measuring intangible assets”, available at: www.sveiby.com/portals/0/articles/IntangibleMethods.htm (accessed 22 August 2010).

Vaivio, J. (2004), “Mobilizing local knowledge with ‘provocative’ non-financial measures”, European Accounting Review, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 39–71.

Yin, R. K. (2003), Case Study Research: Design and Methods, Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.