Table 25.1 Knowledge management practices and epistemological paradigms (extracted from Marr et al., 2003)

p.399

KEY CONTRIBUTIONS TO THE INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL FIELD OF STUDY

Göran Roos

Introduction

Since the late 1990s, together with my colleagues, I have contributed to the field of intellectual capital (IC), and we have arrived at many insights, most of which we have published. This chapter is structured by key contribution domain and is presented in order of criticality of contribution and the associated publications are listed in the references.

The key contributions can be summarized as follows. First, the development of a proper measurement system – the conjoint value hierarchy measurement system or CVH for short – for capturing the value of real business systems including or involving IC. Second, the distinction between stocks (the balance sheet view) and flows or transformations (the profit and loss statement view). Third, the resource taxonomy grounded in economic behaviour of resources. Fourth, clarification of the distinction between intangibles and IC resources. Fifth, the IC Navigator as a strategic tool addressing the weaknesses in the resource-based view of the firm (RBV) toolbox. Sixth, recommendations for how to regulate around IC reporting and a methodological approach for the disclosure of IC. Seventh, a theoretically grounded and empirically verified relationship between epistemological paradigm held, resource and resource transformation managed, strategic logic and potential for competitive advantage. Eighth, the positioning and empirical verification of the IC lens as an important component in business model innovation. And finally, ninth, the application of the IC lens to the meso-economic level to inform policy decisions.

Measurement and evaluation

The key contributions in this area fall into two domains: the distinguishing between measurement systems (with all the associated requirements), and the performance evaluation tools.

Conjoint value hierarchy measurement system

The work undertaken with Dr Stephen Pike over a 15-year period has resulted in the CVH, which is a proper measurement system. Below is the summary of the key issues and main contributions (extracted from the key publications: Pike and Roos, 2004, 2007; Pike et al., 2005; with some modifications).

p.400

Measurement is the process of assigning numbers to things in such a way that the relationships of the numbers reflect the relationships of the attributes of the things being measured. This definition of measurement applies not just to simple and familiar measurements, such as distance and mass, but also to the measurement of complex things, such as the value of businesses that need diverse sets of attributes to describe them. The construction of a measurement system requires the application of measurement theory, a branch of applied mathematics. The fundamental idea of measurement theory is that a measurement is not the same as the object being measured but is, instead, a representation of it. This means that if conclusions are to be drawn about the object, it is necessary to consider the nature of the correspondence between the attribute and the measurement. Proper use of measurement theory greatly reduces the possibility of making meaningless statements; for example, although 30 is twice 15, a temperature of 30°C is not twice a temperature of 15°C, since there is no simple correspondence between the numerical measure and the object. The formalization of measurement theory is a surprisingly recent development. The ideas of the modern theory of measurement date only from the 19th-century work of Helmholtz (1887), which laid the basis for one-dimensional extensive relational measurement theory. The formalization of measurement theory was motivated by the need to understand what it means to measure things in the social sciences. The catalyst for the formalization of measurement theory is generally accepted to be the psychologist S. S. Stevens (1946), with later interest from scientists in the field of quantum physics, although it was not until the 1970s that measurement was fully axiomatized (Scott and Suppes, 1958; Suppes and Zines, 1963; Krantz et al., 1971; Narens, 1985; Suppes et al., 1989; Luce et al., 1990). It was shown that numerical representations of values and laws are only numerical codes of algebraic structures representing the real properties of these values and laws. Thus, hierarchical structures are primary representations of values and laws. When applying proper measurement systems for the measurement of the value of something, four important outcomes from the independence of value definition must be considered:

1 the object to be measured or valued and the context in which the object subsists must be precisely defined;

2 the definition is inclusive in its detail of all opinions and requirements from all stakeholders;

3 all participants (stakeholders) have equal dignity or importance, at least to begin with;

4 every participant is accountable for the veracity of his/her position.

When dealing with complex objects, the principles of axiology must be extended and the easiest way of doing this requires the use of multi-attribute value theory (MAVT). Note that MAVT is often considered to be similar to multi-attribute utility theory (MAUT) but with no uncertainties about the consequences of the alternatives, whereas MAUT explicitly recognizes uncertainties (Keeney and Raiffa, 1976).

MAVT allows the representation of complex entities using a hierarchical structure in which the elements of value are contained in a complete set of mutually independent attributes. Such value measurement structures can be made operational in conjoint structures by the incorporation of algorithms to represent the subjective judgements made by stakeholders. For reliable use, it requires the algorithms to be compliant with measurement theory in all places. The basic idea in conjoint measurement is to measure one attribute against another. Clearly, this must involve common scales, and one in which the scale ends have a defined meaning. In practice, making scales commensurable requires normalization onto a 0 to 1 scale and that input data are expressed on a ratio scale. If other scaling systems are used, such as interval and ordinal, Tversky et al. (1988) have shown that they are incompatible with the axioms of measurement theory and commensurable scales cannot be constructed with them.

p.401

Using the above, we developed the CVH as a proper value measurement system. The development of a CVH measurement system to measure the value of a given object follows the following process. In the first step, the object in its context is defined by the stakeholders, taking into strict account the legitimacy of the stakeholder and the implied comparison that the context will provide. A hierarchical measurements system is an ordered triple, a non-empty set 𝔸, containing all the attributes (ai) of the entity, the relationships (ri) between them, and the operations (oi) upon them. These are usually expressed as:

This means that for a set containing n elements:

The only test that can be applied to demonstrate compliance with these conditions is proof by exhaustion. The hierarchical structure constructed along these lines simply describes the object to be measured but nothing more. It shows what ‘ought’ to be measured.

The second step is to build an operational isomorph. The practical problem that is almost always encountered is that some of the attributes that ‘ought’ to be measured cannot be easily measured in practice, and thus the stronger condition of homeomorphy cannot be invoked.

Thus, our description of the entity to be measured () appears as an isomorphic measurement structure in which the attributes ai are replaced in part or in whole by proxies bi. As the measurement structure is an isomorph, ri and oi are preserved and the measurement structure is represented by another ordered triple, 𝔹, where:

It is necessary to ensure that the proxies (which can be measured reliably and reproducibly) are acceptable. Since these are not exactly the same as the defined attributes that ‘ought’ to be measured, it is necessary to test them to ensure that the conditions of completeness and distinctness have not been violated, but most of all that the aggregated meaning of 𝔹 approximates to 𝔸 in a way that is acceptable to the stakeholders. The method to test this is, again, proof by exhaustion, and the tests are as follows

Assuming true isomorphism and , that is, b 6¼ {bbk}, then and

It is easy to show and quantify the difference that sloppy mathematics makes to the results generated by a measurement system, but it is much harder to quantify the difference made by ill-chosen proxy measures. Given an acceptable isomorphic measurement system 𝔹, the measurable attributes are bi with relationships ri. All that is now needed is to consider the nature of the binary operations oi.

The simplest of aggregation algorithms is weighted addition, with aggregated value V of n attributes defined as:

p.402

The simplicity of the weighted addition algorithm is often problematic, as it does not have the ability to show complex combination behaviours. This is especially important when the loss of performance of one combining attribute should lead to a complete loss of value in the combined higher-level attribute and this cannot be compensated for by a contribution from the other combining attribute. Marichal (1998) gives an excellent account of aggregation functions and their properties.

When a measurement system is used, the results are dependent to a large degree on the nature of the combination algorithm, which must be selected with care and conform to certain conditions of propositional logic. Failure to do this often introduces catastrophically large and variable errors into calculations. The key propositions that an algorithm must satisfy are those of commutativity and associativity, and they can be proved by algebraic means:

(𝒇 ○ 𝒈) ○ 𝒉 = 𝒇 ○ (𝒈 ○ 𝒉) = 𝒇 ○ 𝒈 ○ 𝒉 (associativity)

𝒇 ○ 𝒈 = 𝒈 ○ 𝒇 (commutativity)

where ○ is the generalized binary operation of the aggregation function.

The penultimate step in constructing a measurement system is to customize copies of it so that it represents the behaviours of the individual stakeholders. This step ensures compliance with axiological requirements, in that the individual’s views are maintained without interference or the averaging of those results from consensus processes. In practice, this means asking for opinions on the relative importance of the attributes, the natures of the attribute combinations, and the limits of performance.

In complex value measurement systems like the CVH, native performance scales are collapsed onto a non-dimensional value scale, which is normalized, between 0 and 1. The task is to define what 0 and 1 mean. It is usual to set 0 as that performance level that just becomes useful – in other words, ‘the threshold of uselessness’. The meaning of 1 has two common alternatives: either that it means the ‘best in class’ or that it is some internally set strategic target. The choice between them is decided by the user of the CVH, but it is important that the basis be known.

The final step in producing a measurement system concerns the performance data to be used to operate the measurement system. All performance measures have two parts, the amount and the scale, but it is important to realize that there are many types of scale. If reliable results are to be obtained, then it is important that data are collected on an appropriate scale. For the purposes of proper measurement, only ratio or absolute scales are acceptable.

Bearing in mind the multiplicity of units that may arise and the fact that a measurement system requires a meaningful 0 to 1 scale, all data inputs must be commensurable, which, in practice, means normalizable. Some other conditions are also required of performance data to ensure that the measurement system functions properly. These are that:

(X ≥ Y) if and only if (X + Z) ≥ (Y + Z) (monotonicity)

(X + Y) > X (positivity)

p.403

There exists a natural number n such that:

(nX ≥ Y) where (1X = X) and (n + 1)X = (nX + X) (Archimedean condition)

This is an example of a third part use of CVH in a situation where a proper measurement system is required (see, for example, Millar et al., 2010).

Taxonomy, stocks and flows, and the IC Navigator

Given that IC as a lens can be seen as an extension of the resource-based theory of the firm, some key contributions come from aligning the IC lens with the resource-based view (RVB) of the firm as well as extending the IC lens to address weaknesses identified in the RBV of the firm.

The RBV of the firm originates implicitly with Barnard (1938), Selznick (1957), Chandler (1962), Sloan (1963), Rumelt (1974), Chandler (1977), and notably Penrose (1959), with articulation and further developments by Rumelt (1984), Wernerfelt (1984), Barney (1986), Dierickx and Cool (1989), and Barney (1991). Although, as identified by Seoudi (2009), the RBV is actually one of three distinct “strategic views” of the firm (the others being the dynamic capability view (exemplified by the writings of Nelson and Winter, 1982; Teece et al., 1997) and the competence-based view (exemplified by Hamel and Heene, 1994; Sanchez and Heene, 1997)), for our purposes they can all be addressed in the same way since in the end, they all result in the same issues that require addressing.

Examples of the first is the initial contribution based on a set of firm cases that identified the importance of distinguishing between stocks and flows of IC (which complements and enhances the discussion in Dierickx and Cool, 1989) which was published in the heavily cited Roos and Roos (1997).

An example of the second is the issue that follows from Rumelt’s (1984, p. 557) statement that “a firm’s competitive position is defined by a bundle of unique resources and relationships and that the task of general management is to adjust and renew these resources and relationships as time, competition, and change erode their value”. This requires management to have access to a tool that would allow it to evaluate the effectiveness by which it deploys the different resources in its resource bundle. It also requires a taxonomy for resources since the resources that a firm may have at its disposal have different characteristics. They may be non-appropriable (Meade, 1952; Bator, 1958; Arrow, 1974; Dierickx and Cool, 1989), firm-specific or co-specialized (Williamson, 1979, 1985; Teece, 1986; Dierickx and Cool, 1989), exhibit time compression diseconomies (Scherer, 1967; Mansfield, 1968; Reinganum, 1982), asset mass efficiencies or economies in the accumulation of resources or increasing returns (Wilson and Hlavacek, 1984; Dierickx and Cool, 1989; Cool et al., 2016), interconnectedness of asset stocks (Dierickx and Cool, 1989; Garud and Nayyar, 1994), asset erosion (Dierickx and Cool, 1989), causal ambiguity (Lippman and Rumelt, 1982; Dierickx and Cool, 1989), learning-curve economies (Sanchez and Heene, 2004), capture of the value of positive externalities (Sanchez, 1999, 2002), and/or committed and motivated resources (Sanchez, 2008).

This raises the question of how to characterize and group resources based on attributes. The IC literature has synthesized the insights relating to resources from both the strategic and the economic literature and based on this produced a resource distinction tree (Roos et al., 2005). The contribution made here was a joint effort that commenced as joint work with Leif Edvinsson whilst at Skandia in the form of contributions to the supplements to Skandia’s Annual Report for the years 1996 and 1997 including IC Index simulations (Skandia, 1996a, 1996b, 1997), and was further developed in the two consecutive books, Roos et al. (1997, 2005), where the 2005 book is a substantial refinement of the taxonomy and framework put forward in the first book. The result is a framework that allows all resources to be grouped under one of five headings based on their characteristics: monetary, physical, relational, organizational, and human. Under each of these headings it is possible to find both tangible and intangible resources, and a clear understanding of this distinction was developed and published in Ballow et al. (2004).

p.404

Following Rumelt’s 1984 statement, Barney (1986) points out that once relevant resources have been acquired they can be combined and recombined in a variety of ways to implement different strategies. From this follows that the way these resources are combined will determine the success by which the strategy is implemented. In other words, a firm’s competitive position fundamentally relates to the uniqueness of a bundle of resources (Dierickx and Cool, 1989). The way the firm chooses to combine and deploy resources may be more or less effective, and high effectiveness requires an understanding of the cause and effect relations between deployment decisions and economic returns (Lippman and Rumelt, 1982). This view is echoed in Martín-de-Castro et al. (2006) who state (grounded in Grant, 1991; Amit and Schoemaker, 1993; Prahalad and Hamel, 1990; Teece et al., 1997) that capabilities arise from the coordination of different resources and hence are dynamic and more complex than resources.

Based on this, Barney (1986, p. 1238) poses the question: “How can firms become consistently better informed about the value of strategies they are implementing than any other firms?” The answer provided by Barney is that in principle there are two different approaches. The first approach being to analyse the external environment in which the firm operates, but it is unlikely that this will generate the insights needed for the firm to achieve supra-normal returns since both the tools and the information required as well as the skill needed to put the tools into use for this type of analysis are available in the public domain and hence most firms pursuing this route will arrive at approximately the same conclusions. Thus Barney (1986, p. 1238) concludes, “Analysing a firm’s competitive environment cannot, on average, be expected to generate the expectational advantages that can lead to expected above normal returns in strategic factor markets”. The second approach is to analyse the resources that the firm has at its disposal. This information does not exist in the public domain, which would, given the access to tools and the skill to use such tools, provide the basis for supra-normal returns. At the time of Barney’s (1986) writing, neither the tools nor the skills to use them existed but this problem articulation formed the impetus for the development of the IC Navigator as the tool to satisfy this need.

The IC Navigator work has taken around two decades to come to fruition in the form of a workable, well-grounded, and practical approach that allows management to identify the effectiveness by which it deploys its resource portfolio as well as raising questions, the answers to which will provide for the improvement of this effectiveness. This work aimed to do what Sanchez (2008) later articulates as the failure of the RBV to provide an adequate conceptual basis for identifying which entities can be considered resources that are “strategically valuable” to a firm in its current competitive context or which entities will be resources that will become strategically valuable in future competitive contexts. To address this failure, the RBV would have to offer conceptually clear, consistent, and delimited characterizations of the functional or behavioural properties of resources that would enable the unambiguous identification of resources, the distinguishing of different kinds of resources, and the drawing of logical inferences about the different ways in which different kinds of resources contribute to strategic value creation. The RBV provides no consistent, generally applicable conceptual basis for systematically identifying and evaluating resources in ways that would distinguish firm attributes that are “strategically valuable” resources from those firm attributes that are not. Hence, RBV researchers attempting to test the RBV’s core proposition empirically have had no recourse but to revert to such arguments based on ad hoc and ex post characterizations of resources that directly result in resources identified ex post as being strategically valuable (by invoking some ad hoc environmental model or SWOT framework) were by that very fact the ex ante strategically valuable resources responsible for a firm’s or firms’ future success. This poses a tautological problem that limits the empirical value of the RBV framework. To address this failure, the RBV must develop a rigorous definition of resources that provides a consistent and coherent conceptual basis for distinguishing the different ways in which different kinds of firm attributes can contribute to creating strategic value and thus qualify as resources.

p.405

Further, the RBV fails to propose a credible chain of causality explaining how firms can actually use resources to create strategic value. Given this fundamental omission, the RBV fails to offer an adequate conceptual basis for systematically deriving hypotheses about how different kinds of resources and organizational processes for using resources may result in effective or ineffective realization of the strategic value of a firm’s resources. The practical consequence of this fundamental omission is that the RBV has no theoretical basis for providing consistent counsel to managers about how they might improve their skills in defining and implementing organizational processes for using their firm’s resources. To address this failure, the RBV must develop a clear understanding of how resource deployments create value and how changes in this resource deployment structure will impact the value creation.

Early iterations of the IC Navigator can already be seen in Roos et al. (1997) with consecutive insights, applications, and progression shown in Dragonetti and Roos (1998a, 1998b, 1998c), Roos and Lövingsson (1999), Roos and Jacobsen (1999), Rylander et al. (2000), Peppard and Rylander (2001a, 2001b), Gupta and Roos (2001), Roos et al. (2001, 2005), Chatzkel (2002), Fernström and Roos (2004), Fernström et al. (2004), Pike et al. (2005), Peng et al. (2007), Uchida and Roos (2008), Roos and Pike (2008), Chung et al. (2010), Pike and Roos (2011), Roos (2011c, 2014a), Burton et al. (2013), and De Zubielqui et al. (2015). The most complete description can be found in Roos (2014a). The IC Navigator is now a well-grounded, proven (applied in more than 1,000 firms), practical, and useful strategic tool that addresses all the weaknesses identified by Sanchez (2008) and also later by El Shafeey and Trott (2014).

Reporting and disclosure of IC

Reporting and disclosure of intangibles have been a feature of the IC landscape since its inception. Initial contributions to this field were made together with Leif Edvinsson for the supplements to Skandia’s Annual Report for the years 1996 and 1997 including IC Index simulations, and was further developed in the book Roos et al. (1997) and the paper Rylander et al. (2000).

In Gupta et al. (2003), the first step towards a broader understanding of the corporate governance issues was taken by discussing corporate governance from the viewpoints of agency theory, stewardship theory, stakeholder theory, organizational theory, resource dependence theory, resource-based theory, and the IC perspective. Gupta et al. (2003) outline the complexities and propose a first version of a governance model in descriptive terms that can be linked to financial performance; establishes the value drivers of corporate control that are dynamically linked to financial performance measures such as share price; will provide a prescription of the performance measures (and expectations related thereto) that will necessarily be included in any corporate governance systems; provides the strategic management intervention points that are fundamental to managing the system (the short list of what should be managed where in the system); and identifies the trade-offs that inevitably need to be, and are, made.

p.406

This discussion was further refined in Burgman and Roos (2005) by identifying 12 influences that promote the need for operational and IC disclosure and reporting. To this discussion is then added the three necessary conditions for an IC reporting framework: a business enterprise classification scheme; the legal test for negligence and the requirement to report on operations; and a standard set of measures that fulfil the criteria for good information as relates to financial reporting and disclosure (validity; reliability; credibility of issuer; completeness; consistency; comprehensiveness; coverage or scope; objectivity relating to the bias or opinion expressed when the issuer interprets or analyses facts; accuracy, that is, the factually irrefutability, error rate, restatement rate, etc.; timeliness, that is, the modernity of the information; utility or usefulness; accessibility, that is, ease of use).

In Burgman and Roos (2006a, 2006b, 2007) and Burgman et al. (2007), the previous discussions are concluded by presenting a set of recommendations for companies that realize the value of reporting on IC and are about to embark on the journey of finding a suitable model for doing this. These recommendations include, first, finding a suitable model for disclosing IC information, which is a challenging task since it is about changing both internal and external stakeholders’ way of thinking and view of the company. It is also about turning something that is today complex and dynamic in nature into something simple and practical. Therefore, it is of utmost importance that IC is demystified and laid bare in order to gain support within and outside of the company on its identification, quantification, and management. Second, finding a suitable model to use in its demystification, the organization first must assess and define its own management needs and how to go about addressing them. This is about predicting changes and their consequences, making sure that the management team fully supports the idea, and making sure that the model is aligned with the strategy of the company. Moreover, the company should take its own and others’ experiences and insights into account and establish the factors critical to achieving as well as barriers to success. It is not recommended to launch into establishing a measurement system without having a sound understanding of the grounding principles of measurement. Sound and clear mental models are needed to be able to develop effective management systems. Third, the implementation is best done step by step. That way, feedback from internal and external stakeholders can be integrated along the way. In deciding which approach to take and which content to choose, the strategy of the company must be considered and used as a basis for the decision. Finally, the key performance indicators are defined and existing data is mapped. This is the stage where stakeholders get to comment on a draft reporting model. A methodology for arriving at what is to be reported is also proposed:

1 Identify drivers of enterprise value:

a establish value drivers and impacted financial accounts from standard balance sheet, profit and loss, cash flow statements and notes to the accounts;

b identify any ‘missing’ value drivers (generally investments in IC being expensed) and nominate these for management accounting balance sheet inclusion;

c capitalize ‘investments’ in IC resources and establish amortization schedules.

2 Identify primary value creating business processes:

a establish the company’s value creating mega-business processes and sub-processes;

b identify the key value determining resources and activities (transformations) within each mega process;

c identify the key resource state (stock) and activity (transformation) performance metrics that give a comprehensive insight into how the company manages for value.

p.407

3 Functional resource utilization:

a identify the key functional resources being consumed in the administration of the value creation mega processes and sub-processes;

b establish the functional allocation of resources to the various mega- and sub-processes (e.g. from sales and marketing, accounting and finance, procurement, etc.);

c establish the revenue and cost implications of the functional allocation;

d establish the mark-to-market value of all the management accounting balance sheet resources (including all relevant IC resources).

4 Reporting and disclosure:

a establish the content and timing of operational and IC reporting and disclosure based on

i the value of such information to users

ii the legal concept of neglect.

Finally, accepting that no international rules exist for the reporting of IC, Burgman and Roos (2006a, 2006b, 2007) and Burgman et al. (2007) state that when the time for regulating comes, the following conditions should hold for IC reporting if rules and regulations are devised. First, operational reporting should be required as a complement to financial reporting in each and all reporting environments for publicly listed enterprises, the content and extent of which should be left to the company to decide. Second, the content of IC reporting should be established within the context of principles-based reporting and to draw its legal force from the test of neglect (of duty to information users). Third, IC reporting should be an embedded part of operational reporting and not proposed as a voluntary adjunct to either financial reporting or operational reporting. Fourth, there should be a regulatory sanctioned ‘home’ for operational reporting within the context of the reporting and disclosure legislative requirements within each legislative jurisdiction – whether at the country or supra-country (e.g. European Community) level. Examples of existing ‘homes’ that are being used to some extent for this purpose are the Management Discussion and Analysis (MDandA) in the US and Canada, and Management Commentary ‘proposal’ being discussed by the IASB. Fifth, the content of IC reporting should then be determined by reference to the enterprise’s relevant business model/s – value chain, value shop, or value network – and an understanding of the specific drivers of enterprise value – resource states and resource creating and depleting activities, and capabilities – that are causally linked to value and its creation. Business model articulation may occur at the industry GICS (6-digit) or sub-industry GICS (8-digit) levels, with business models being identified according to the degree of homogeneity of business conduct among competitive peers. Sixth, independently, standards for resource measurement and activity performance measurement should be developed by standard setters (like the IASB) or professional bodies (like the Association of Certified Chartered Accountants) since there will need to be a consistent set of expectations in relation to the comprehensiveness and quality of data preparation as well as its interpretability. Seventh, finally, the mapping of capitalized IC resources for management purposes back to the financial accounts should be standardized. The credibility of IC recognition will only occur when managerially accounted for on an historical cost basis. This does not mean that we propose that IC should be reported on in the financial accounts, rather that when IC is reported on in the relevant disclosure section of an annual report and a value is to be attributed to an IC item, then it would be on the net historical cost of the investment made in it. What will be important to information users will be the identification of the IC resource as being causally connected to enterprise value in the eyes of management. What that contributes to overall enterprise value is up to the investors to decide. No attempt should be made by the company to mark-to-market except in the limited circumstances of self-generating and regenerating asset equivalents such as may exist with human capital.

p.408

Epistemology, knowledge management, strategic logics, IC, and competitive advantage

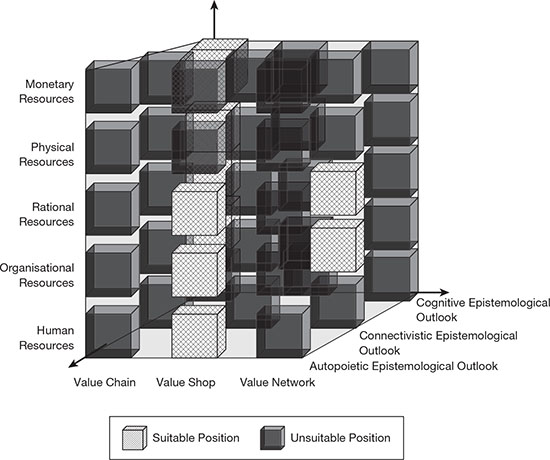

Epistemology as a concept within IC was first introduced in Pike and Roos (2002) and in Gupta et al. (2002) based on an epistemology classification tool developed. This tool was further deployed to create the analysed data for the paper by Marr et al. (2003). This paper allowed the identification of suitability of different knowledge management practices for different epistemological paradigms (see Table 25.1). The epistemological paradigms were extracted from Von Krogh and Roos (1995) and operationalized by Pike and Roos (2002). The three paradigms used are cognitivist, connectivist, and autopoietic. Cognitivists consider the identification, collection, and central dissemination of information as the main knowledge development activity. Organizations are considered as open organizations that develop increasingly accurate pictures of their pre-defined worlds through the assimilation of new information. Knowledge is developed according to universal rules; hence the context of the incoming information is important. Connectivists have many similarities to the cognitivist viewpoint but a difference being that there are no universal rules. As rules are team-based and vary locally, organizations are seen as groups of self-organized networks dependent on communication. The connectivists believe that knowledge resides in the connections and hence focus on the self-organized dispersed information flow. Autopoietics consider the context of information inputs as unimportant and it is seen as data only. The organization is a system that is simultaneously open (to data) and closed (to information and knowledge). Information and knowledge cannot be transmitted easily since they require internal interpretation within the system according to the individual’s rules. Thus, autopoietics develop individual knowledge, and respect that process in others.

These insights were further refined as relates to the knowledge aspects of IC resources in Roos (2005a, 2005b). This work substantiated the claim that the epistemological outlook of people in organizations has a substantial impact on the effectiveness of the firm’s value creation and needs to be aligned with both the type of IC resources that form the basis for the firm’s competitive advantage and the type of strategic logics that dominate in the firm. The findings are that the higher the alignment is between the pairs of strategic logics (using the terminology of Stabell and Fjeldstad, 1998) and epistemological paradigms (Value Chain ↔ Cognitivist; Value Network ↔ Connectivist; Value Shop ↔ Autopoietic) the more effective the value creation of the firm. A further insight is that with the epistemological paradigms held by the individuals involved in executing and managing resource transformations with the taxonomy of these transformations a clearer picture emerges of how to maximize effectiveness using people holding appropriate epistemological paradigms to achieve this maximization (Table 25.2).

Figure 25.1 shows the insight as it relates to suitable combinations of epistemological paradigm held, strategic logic, resource managed, that can form the basis for a competitive advantage.

p.409

Table 25.1 Knowledge management practices and epistemological paradigms (extracted from Marr et al., 2003)

p.410

Table 25.2 Resources, resource transformations, and epistemologies (extracted from Roos, 2005a)

The role of IC in business model innovation

As the concept of business models became widely popularized and adapted, with a major contribution by Osterwalder (2004), it became clear that the relationships between the IC lens and the business model lens needed to be clarified. The focus that was chosen was that of business model innovation. In a series of publications this problem was addressed from both a theoretical and an empirical point of view (Roos and Pike, 2008; Peng et al., 2011; Roos, 2011a, 2011b, 2012a, 2013, 2014b, 2016; Roos and Fusco, 2014; Roos and O’Connor, 2014; Dissanayake et al., 2015; O’Connor and Roos, 2016). Based on this research it was found that the existing business model dimensions as provided by the literature are not aligned with a modern manufacturing operating environment. Instead the 21 relevant business model dimensions for this environment were identified and are shown in Table 25.3 in the order in which they will be addressed in a business model innovation process. The top three in terms of criticality for creating the new business model, as identified empirically, are marked in bold italics.

Roos (2014b) also contains a thorough literature review of the dimensions of a business model as articulated by 80 publications during the period 1993–2010 (excluding those publications that use already published dimensions).

p.411

Figure 25.1 Key contribution to the relationship between epistemological paradigm held, resource and resource transformation managed, strategic logic, and potential for competitive advantage (Roos, 2005a)

Table 25.3 Empirically and theoretically derived and verified business model dimensions for manufacturing firms (Roos, 2014b)

p.412

As can be seen from Table 25.3, it is clear that not only does the IC lens fill a void in the business model innovation dimensions but it is empirically considered to be one of the three most important dimensions.

The use of the IC lens on the meso-economic scale

The interest in looking at the contribution that the IC lens can make on the meso-economic level was first shown in Roos and Gupta (2005), Peng et al. (2012), and the sector review by Roos (2012b). This laid the groundwork for several applications of the IC lens to sectors and clusters, normally as a complement to technology roadmapping. Examples of these applications can be found in Ahlqvist et al. (2013), Dufva et al. (2013), Kraatz et al. (2014), Roos et al. (2014), Roos (2014c), Roos and O’Connor (2015), and O’Connor et al. (2015).

It is clear that this is a very useful complement that substantially enriches the basis for policy decisions relating to the meso-economic level and the use of an IC lens. At present, we are applying the IC lens as a complement to economic complexity theory and the first publication is Reynolds et al. (2017).

Conclusion

Since the late 1990s, my colleagues and I have made some key contributions to the field of IC. In the author’s personal view, the greatest contributions can be found in the development of the IC Navigator to address the missing tool for the RBV of the firm and also as a complement in business model innovation and in the management of IC in general.

This is followed by the contribution to the ability to apply measurement to the field of IC (as well as other more complex objects with difficult or multi-dimensional attributes of value that must be captured) in the form of the CVH.

Neither of these contributions nor the contributions to the field of reporting and disclosure would have been possible without the contributions to the taxonomy of the field, and addressing confusions as to what stocks and flows of resources exist as well as addressing the confusion around the distinction between intangibles and IC.

p.413

It is clear from the work that is presently ongoing on the meso-economic scale that the IC lens is useful and able to contribute to insights around value creation on multiple scales.

References

Ahlqvist, T., Dufva, M., Kettle, J., Vanderhoek, N., Valovirta, V., Loikkanen, T., Roos, G., Hytönen, E., Niemelä, K., and Kivimaa, A. (2013), “Strategic roadmapping, industry renewal, and cluster creation: The case Green Triangle”, Paper presented at 6th ISPI Innovation Symposium – Innovation in the Asian Century, 8–11 December, Melbourne, Australia.

Amit, R. and Schoemaker, P. J. (1993), “Strategic assets and organizational rent”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 33–46.

Arrow, K. E. (1974), The Limits of Organization, W. W. Norton and Company, New York

Ballow, J. J., Thomas, R. J., and Roos, G. (2004), “Future value: The $7 trillion challenge”, Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 71–76

Barnard, C. (1938), The Functions of the Executive, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Barney, J. B. (1986), “Strategic factor markets: Expectations, luck, and business strategy”, Management Science, Vol. 32, No. 10, pp. 1231–1241.

Barney, J. B. (1991), “Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage”, Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 99–120.

Bator, F. M. (1958), “The anatomy of market failure”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, pp. 351–379.

Burgman, R. and Roos, G. (2005), “Empirical and structural evidence for the increasing importance of intellectual capital reporting: Implications for European companies”, paper presented at 1st EIASM Workshop on Visualising, Measuring, and Managing Intangibles and Intellectual Capital, 18–20 October, Ferrara, Italy.

Burgman, R. and Roos, G. (2006a), “Operational and intellectual capital reporting: A top-down risk-based approach to identifying, quantifying and reporting on enterprise value drivers”, paper presented at 2nd EIASM Workshop on Visualising, Measuring, and Managing Intangibles and Intellectual Capital, 25–27 October, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Burgman, R. and Roos, G. (2006b), “The information needs of internal and external stakeholders and how to respond: Reporting on operations and intellectual capital”, paper presented at 2nd EIASM Workshop on Visualising, Measuring, and Managing Intangibles and Intellectual Capital, 25–27 October, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Burgman, R. and Roos, G. (2007), “The importance of intellectual capital reporting: Evidence and implications”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 8, No. 1, pp. 7–51.

Burgman, R., Roos, G., Boldt-Christmas, L., and Pike, S. (2007), “Information needs of internal and external stakeholders and how to respond: Reporting on operations and intellectual capital”, International Journal of Accounting, Auditing and Performance Evaluation, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 529–546.

Burton, K., O’Connor, A., and Roos, G. (2013), “An empirical analysis of the IC Navigator approach in practice: A case study of five manufacturing firms”, Knowledge Management Research and Practice, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 162–174.

Chandler Jr., A. D. (1962), Strategy and Structure, The MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Chandler Jr., A. D. (1977), The Visible Hand, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Chatzkel, J. (2002), “A conversation with Göran Roos”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 3, No. 2, pp. 96–117

Chung, S. Y., Peng, T. J. A., Roos, G., and Pike, S. (2010), “Intellectual capital resource transformation and inertia in inter-firm partnership”, paper presented at the SMS Special Conference: Intersections of Strategy Processes and Strategy Practices, Track: Networks and Alliances for Competitive Advantage, 17–20 March, Kittilä, Finland.

Cool, K., Dierickx, I., and Almeida, L. (2016), “Asset mass efficiencies”, The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Strategic Management, pp. 1–8.

De Zubielqui, G. C., O’Connor, A., and Seet, P. S. (2015), “Intellectual capital system perspective: A case study of government intervention in digital media industries” in Roos, G. and O’Connor, A. (Eds), Integrating Innovation: South Australian Entrepreneurship Systems and Strategies, University of Adelaide Press, Adelaide, Australia, pp. 277–302.

p.414

Dierickx, I. and Cool, K. (1989), “Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage”, Management Science, Vol. 35, No. 12, pp. 1504–1511.

Dissanayake, M., O’Connor, A, and Roos, G. (2015), “How does a government business support program influence business growth? The case of a business model innovation program in Australia”, 2015 Australian Centre for Entrepreneurship Research Exchange (ACERE) Conference, 3–6 February, Adelaide, Australia.

Dragonetti, N. C. and Roos, G. (1998a), “Assessing the performance of government programmes: An intellectual capital perspective”, paper presented at the 18th Strategic Management Society Conference, 1–4 November, Orlando, Florida.

Dragonetti, N. C. and Roos, G. (1998b), “La evaluación de Ausindustry y el business network programme: Una perpectiva desde el capital intelectual”, Boletín de estudios económicos, Vol. 53, No. 164, pp. 265–280.

Dragonetti, N. C. and Roos, G. (1998c), “Efficacy and effectiveness of government-sponsored programmes: An intellectual capital perspective” paper presented at the 2nd World Congress on Intellectual Capital, 21–26 January, Hamilton, ON.

Dufva, M., Ahlqvist, T., Kettle, J., Vanderhoek, N., Valovirta, V., Loikkanen, T., and Roos, G. (2013), “Future pathways for radical transformation of an industry sector”, paper presented at the 6th ISPIM Innovation Symposiu Innovation in the Asian Century, 8–11 December, Melbourne, Australia.

El Shafeey, T. and Trott, P. (2014), “Resource-based competition: Three schools of thought and thirteen criticisms”, European Business Review, Vol. 26, No. 2, pp. 122–148.

Fernström, L. and Roos, G. (2004). “Differences in value creating logics and their managerial consequences: The case of authors, publishers and printers”, International Journal of the Book, Vol. 1, 493–506.

Fernström, L., Pike, S., and Roos, G. (2004), “Understanding the truly value creating resources: The case of a pharmaceutical company”, International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 105–120.

Garud, R. and Nayyar, P. R. (1994), “Transformative capacity: Continual structuring by intertemporal technology transfer”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 15, No. 5, pp. 365–385.

Grant, R. M. (1991), “The resource-based theory of competitive advantage: Implications for strategy formulation”, California Management Review, Vol. 33, No. 3, pp. 114–135.

Gupta, O. and Roos, G. (2001), “Mergers and acquisitions through an intellectual capital perspective”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 297–309.

Gupta, O., Pike, S., and Roos, G. (2002), “Evaluating intellectual capital and measuring knowledge management effectiveness”, in Performance Measurement and Management: Research and Action, Papers from the Third International Conference on Performance Measurement and Management, PMA Centre for Business Performance, Cranfield, UK.

Gupta, O., Pike, S., Roos, G., and Burgman, R. (2003, January), “Intellectual capital and improved corporate governance”, paper presented at the 6th World Congress on the Management of Intellectual Capital and Innovation, 15–17 January, Hamilton, ON.

Hamel, G. and Heene, A. (Eds), (1994), Competence-Based Competition, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

Helmholtz, H. (1887), “Zahlen und Messen erkenntnistheoretisch betrachtet”, in Philosophische Aufsatze, Fues’s Verlag, Leipzig, pp. 17–52. (Trans. Bryan, C. L. (1930). Counting and Measuring, Van Nostrand, New York).

Keeney, R. and Raiffa, H. (1976). Decisions with Multiple Objectives: Preferences and Value Tradeoffs, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

Kraatz, J. A., Hampson, K. D., Parker, R. L., and Roos, G. (2014), “What next? Future directions for R&D investment”, in Hampson, K. D., Kraatz, J. A., and Sanchez, A. X. (Eds) R&D Investment and Impact in the Global Construction Industry, Routledge, Abingdon, UK, pp. 284–309.

Krantz, D., Luce, R. D., Suppes, P., and Tversky, A. (1971), Foundations of Measurement, Vol. I, Additive and Polynomial Representations, Academic Press, London.

Lippman, S. A. and Rumelt, R. P. (1982), “Uncertain imitability: An analysis of interfirm differences in efficiency under competition”, The Bell Journal of Economics, pp. 418–438.

Luce, D., Krantz, D., Suppes, P., and Tversky, A. (1990), Foundations of Measurement, Vol. III, Representation, Axiomatization and Invariance, Academic Press, London.

p.415

Mansfield, E. (1968), The Economics of Technological Change, W.W. Norton and Company Inc., New York.

Marichal, J. L. (1998), Aggregation Operations for Multicriteria Decision Aid, PhD thesis, University of Liège, Belgium.

Marr, B., Gupta, O., Pike, S., and Roos, G. (2003), “Intellectual capital and knowledge management effectiveness”, Management Decision, Vol. 41, No. 8, pp. 771–781.

Martín-de-Castro, G., Emilio Navas-López, J., López-Sáez, P., and Alama-Salazar, E. (2006), “Organizational capital as competitive advantage of the firm”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 3, pp. 324–337.

Meade, J. E. (1952), “External economies and diseconomies in a competitive situation”, The Economic Journal, Vol. 62, No. 245, pp. 54–67.

Millar, L. A., McCallum, J., and Burston, L. M. (2010), “Use of the conjoint value hierarchy approach to measure the value of the national continence management strategy”, Australian and New Zealand Continence Journal, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 81–88.

Narens, L. (1985), Abstract Measurement Theory, MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

Nelson, R. R. and Winter, S. G. (1982), An Evolutionary Theory of Economic Change, Belknap Press, London.

O’Connor, A. and Roos, G. (2016), “Visualising intellectual capital transformations for strategic design of entrepreneurial business models”, in Griffith, S., Carruthers, K., and Biemel, M. (Eds), Visual Tools for Developing Student Capacity for Cross-Disciplinary Collaboration, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, Transformative Pedagogies in the Visual Domain Series, Common Ground Publishing. Champaign, IL.

O’Connor, A., Du, K., and Roos, G. (2015), “The intellectual capital needs of a transitioning economy: A case study exploration of Australian sectoral changes”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 466–489.

Osterwalder, A. (2004), The Business Model Ontology: A Proposition in a Design Science Approach, PhD Thesis, University of Lausanne, Switzerland.

Peng, T. J. A., Pike, S., and Roos, G. (2007), “Intellectual capital and performance indicators: Taiwanese healthcare sector”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 538–556.

Peng, T. J. A., Pike, S., Yang, J. C. H., and Roos, G. (2012), “Is cooperation with competitors a good idea? An example in practice”, British Journal of Management, Vol. 23, No. 4, pp. 532–560.

Peng, T. J. A., Yang, J. C. H., Pike, S., and Roos, G. (2011), “Intellectual capitals, business models and performance measurements in forming strategic network”, International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, Vol. 8, No. 3, pp. 328–347.

Penrose, E. T. (1959), The Theory of the Growth of the Firm, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

Peppard, J. and Rylander, A. (2001a), “Using an intellectual capital perspective to design and implement a growth strategy: The case of APiON”, European Management Journal, Vol. 19, No. 5, pp. 510–525.

Peppard, J. and Rylander, A. (2001b), “Leveraging intellectual capital at APiON”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 2, No. 3, pp. 225–235.

Pike, S. and Roos, G. (2002), “Measuring the impact of knowledge management in companies”, paper presented at the 5th World Congress on Intellectual Capital, Hamilton, 16–18 January, Ontario, Canada.

Pike, S. and Roos, G. (2004), “Mathematics and modern business management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 243–256.

Pike, S. and Roos, G. (2007), “The validity of measurement frameworks: Measurement theory”, in Neely, A. (Ed.), Business Performance Measurement: Unifying Theory and Integrating Practice, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK, pp. 218–236.

Pike, S. and Roos, G. (2011), “Measuring and valuing knowledge-based intangible assets: Real business uses”, in Alonso, B. V., Castellanos, A. R., and Arregui-Ayastuy, G. (Eds), Identifying, Measuring, and Valuing Knowledge-based Intangible Assets: New Perspectives, IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp. 268–293.

Pike, S., Fernström, L., and Roos, G. (2005), “Intellectual capital: Management approach in ICS Ltd.”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 6, No. 4, pp. 489–509.

Prahalad, C. and Hamel, G. (1990), “The core competence of the corporation”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 90, pp. 79–91.

Reinganum, J. F. (1982), “A dynamic game of R&D: Patent protection and competitive behaviour”, Econometrica: Journal of the Econometric Society, pp. 671–688.

Reynolds, C., Agrawal, M., Lee, I., Zhan, C., Li, J., Taylor, P., Mares, T., Abedin, F., Morison, J., Angelakis, N., and Roos, G. (2017), “A sub-national economic complexity analysis of Australia’s states and territories”, Regional Studies. Vol. 51, pp. 1–12.

p.416

Roos, G. (2005a), “An epistemology perspective on intellectual capital”, in Marr, B. (Ed.), Perspectives on Intellectual Capital: Multidisciplinary Insights into Management, Measurement and Reporting, Routledge, Abingdon, UK, pp. 196–209.

Roos, G. (2005b), “Epistemological cultures and knowledge transfer within and between organisations”, in Bukh, P. N., Christensen, K., and Mouritsen, J. (Eds), Knowledge Management and Intellectual Capital: Establishing a Field of Practice, Palgrave Macmillan, London, pp. 149–172.

Roos, G. (2011a), “How to get paid twice for everything you do: Integrated innovation management”, Ericsson Business Review, Vol. 2, pp. 55–57.

Roos, G. (2011b), “How to get paid twice for everything you do: Value appropriating innovations”, Ericsson Business Review, Vol. 3, pp. 56–61.

Roos, G. (2011c), “Интегрированное управление инновациями – путь к удвоению отдачи от любой деятельности [Integrated management of innovation is the way to double the impact of any activity]”, Стратегический менеджмент [Strategic Management], Vol. 4, pp. 270–290.

Roos, G. (2012a), “How to get paid twice for everything you do: Innovation management”, Ericsson Business Review, Vol. 1, pp. 45–51.

Roos, G. (2012b), Manufacturing into the Future, Adelaide Thinkers in Residence, Government of South Australia, Adelaide.

Roos, G. (2013), “The role of intellectual capital in business model innovation: An empirical study”, in Ordoñez de Pablos, P., Tennyson, R. D., and Zhao, J. (Eds), Intellectual Capital Strategy Management for Knowledge-Based Organizations, IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp. 76–121.

Roos, G. (2014a), “The Intellectual Capital Navigator as a strategic tool”, in Ordóñez de Pablos, P. (Ed.) International Business Strategy and Entrepreneurship: An Information Technology Perspective, IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp. 1–22.

Roos, G. (2014b), “Business model innovation to create and capture resource value in future circular material chains”, Resources, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 248–274.

Roos, G. (2014c), “Regional economic renewal through structured intellectual capital development”, paper presented at the 11th International Conference on Intellectual Capital, Knowledge Management and Organisational Learning, 6–7 November, Sydney, Australia.

Roos, G. (2016), “Design-based innovation for manufacturing firm success in high-cost operating environments”, She Ji The Journal of Design, Economics and Innovation, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 5–28.

Roos, G. and Fusco, M. (2014), “Strategic implications of additive manufacturing (AM) on traditional industry business models”, paper presented at the Additive Manufacturing with Powder Metallurgy Conference, 18–20 May, Orlando, Florida.

Roos, G. and Gupta, O. (2005), “Strategy and intellectual capital management for dynamic industries”, paper presented at World Congress, 19–21 January, Hamilton, ON.

Roos, G. and Jacobsen, K. (1999), “Management in a complex stakeholder organisation”, Monash Mt Eliza Business Review, Vol. 2, pp. 82–93.

Roos, G. and Lövingsson, F. (1999), “El Proceso CI en el Nuevo Mondo de las Telecomunicacione”, in Güell, A. M. (Ed.) Homo faber, homo sapiens – La gestión del capital intelectual, Ediciones del Bronce, Barcelona, pp. 141–169.

Roos, G. and O’Connor, A. (2014), “The contribution of intellectual capital to servitization of manufacturing firms: An empirical study”, paper presented at the 11th International Conference on Intellectual Capital, Knowledge Management and Organisational Learning, 6–7 November, Sydney, Australia.

Roos, G. and O’Connor, A. (2015), “Government policy implications of intellectual capital: An Australian manufacturing case study”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 16, No. 2. pp. 364–389.

Roos, G. and Pike, S. (2008), “An intellectual capital view of business model innovation”, in Bounfour, A. (Ed.). (2008), Organizational Capital: Modelling, Measuring and Contextualising, Taylor and Francis, UK, pp. 40–62.

Roos, G. and Roos, J. (1997), “Measuring your company’s intellectual performance”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 413–426.

Roos, G., Ahlqvist, T., Dufva, M., Kettle, J., Vanderhoek, N., Hytönen, E., Niemelä, K., Kivimaa, A., Valovirta, V., and Loikkanen, T. (2014), “Regional economic renewal through structured knowledge development within an agglomeration economic framework: The case of the cellulose fibre value chain in the Mt. Gambier region of South Australia”, paper presented at the 9th International Forum on Knowledge Asset Dynamics (IFKAD 2014), 11–13 June. Matera, Italy.

p.417

Roos, G., Bainbridge, A., and Jacobsen, K. (2001), “Intellectual capital analysis as a strategic tool”, Strategy and Leadership, Vol. 29, No. 4, pp. 21–26.

Roos, G., Pike, S., and Fernström, L. (2005), Managing Intellectual Capital in Practice, Butterworth-Heinemann, New York.

Roos, J., Roos, G., Edvinsson, L., and Dragonetti, N. (1997), Intellectual Capital: Navigating in the New Business Landscape, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Rumelt, R. P. (1974), Strategy Structure and Economic Performance, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA.

Rumelt, R. P. (1984), “Towards a strategic theory of the firm”, in Lamb, B. (Ed.), Competitive Strategic Management, Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, pp. 556–570.

Rylander, A., Jacobsen, K., and Roos, G. (2000), “Towards improved information disclosure on intellectual capital”, International Journal of Technology Management, Vol. 20, No. 5, pp. 715–741.

Sanchez, R. (1999), “Modular architectures in the marketing process”, Journal of Marketing, Vol. 63, pp. 92–111.

Sanchez, R. (2002), “Industry standards, modular architectures, and common components: Strategic incentives for technological cooperation”, in Contractor, F. and Lorange, P. (Eds) Cooperative Strategies and Alliances, Elsevier Science, Oxford, UK, pp. 659–687.

Sanchez, R. (2008), “A scientific critique of the resource-base view (RBV) in strategy theory, with competence-based remedies for the RBV’s conceptual deficiencies and logic problems”, Research in Competence-based Management, Vol. 4, pp. 3–78.

Sanchez, R. and Heene, A. (1997), “Reinventing strategic management: New theory and practice for competence-based competition”, European Management Journal, Vol. 15, No. 3, pp. 303–317.

Sanchez, R. and Heene, A. (2004), The New Strategic Management: Organization, Competition, and Competence, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York and Chichester, UK.

Scherer, F. M. (1967), “Research and development resource allocation under rivalry”, The Quarterly Journal of Economics, pp. 359–394.

Scott, D. and Suppes, P. (1958), “Foundation aspects of theories of measurement”, Journal of Symbolic Logic, Vol. 23, pp. 113–128.

Selznick, P. (1957), Leadership in Administration, Harper and Row, New York.

Seoudi, I. (2009), The Resource-capability-competence Perspective in Strategic Management: A Reappraisal of the Epistemological and Theoretical Foundations, PhD Thesis, Department of Economics, School of Graduate Studies. Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland, OH.

Skandia (1996a), Customer Value. Intellectual Capital Supplement to Skandia’s 1996 Annual Report, Skandia, Stockholm.

Skandia (1996b), Skandia and the Intellectual Capital Development, CD-ROM, Skandia, Stockholm.

Skandia (1997), Intelligent Enterprising. Intellectual Capital Supplement to Skandia’s 6-Month Interim Report, Skandia, Stockholm.

Sloan Jr., A. E. (1963), My years with General Motors, Doubleday, Garden City, NY.

Stabell, C. B. and Fjeldstad, Ø. D. (1998), “Configuring value for competitive advantage: On chains, shops and networks”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 19, pp. 413–437.

Stevens, S. S. (1946), “On the theory of scales of measurement”, Science, Vol. 103, pp. 677–680.

Suppes, P. and Zines, J. (1963), “Basic measurement theory”, in Luce, R., Bush, R., and Galanter, E. (Eds), Handbook of Mathematical Psychology Vol. 1, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, pp. 1–76.

Suppes, P., Krantz, D., Luce, D., and Tversky, A. (1989), Foundations of Measurement, Vol. II, Geometrical, Threshold and Probabilistic Representations, Academic Press, London.

Teece, D. J. (1986), “Firm boundaries, technological innovation, and strategic management”, The Economics of Strategic Planning, pp. 187–199.

Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., and Shuen, A. (1997), “Dynamic capabilities and strategic management”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 18, pp. 509–533.

Tversky, A., Slovic, P., and Sattath, S. (1988), “Contingent weighting in judgment and choice”, Psychological Review, Vol. 95, pp. 371–384.

Uchida, Y. and Roos, G. (内田 and ルース, ヨ) (2008), 日本企業の知的資本マネジメント [Intellectual Capital Management for Japanese Firms], Chuokeizai-Sha Publishing, Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo, Japan.

Von Krogh, G. and Roos, J. (1995), Organizational Epistemology, St. Martin’s Press, New York.

Wernerfelt, B. (1984), “A resource-based view of the firm”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 171–180.

Williamson, O. E. (1979), “Transaction-cost economics: The governance of contractual relations”, The Journal of Law and Economics, Vol. 22, No. 2, pp. 233–261.

Williamson, O. E. (1985), The Economic Institutions of Capitalism, Free Press, New York.

Wilson, T. L. and Hlavacek, J. D. (1984), “Don’t let good ideas sit on the shelf”, Research Management, Vol. 27, No. 3, pp. 27–34.