Figure 26.1 Conceptualizations of value

p.418

VALUE CREATION IN BUSINESS MODELS IS BASED IN INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL

And only intellectual capital!

Henrik Dane-Nielsen and Christian Nielsen

Introduction

This chapter offers a novel perspective on how intellectual capital (IC) can be applied to the notion of business models. Our understanding of business models is that IC is present in different forms at all levels of the organization as described by Nielsen and Dane-Nielsen (2010), and is the only real value driver of any type of business model. A business model is thereby a description of how IC is used in the organization to create value. Nielsen (2011, p. 26) asserts that:

A business model driven by intellectual capital may in some ways differ from business models driven primarily by other factors, such as financial capital or natural resources. When intellectual capital drives the business model of a company then competitive advantage may be particularly high, margins high and corporate flexibility good.

Knowledge and IC are important for the creation of value in the knowledge-based organization. However, in this chapter we argue that any type of technological development through the ages has had IC at its core, right from the invention of the plough, gunpowder, and steam engines to computers. In fact, any type of business or service is driven by the knowledge of how to do things. This is essentially because economic activities are driven by IC, and thereby we disagree with the arguments posed by Nielsen (2011) above.

One of the reasons for this is that business models are concerned with delivering a value proposition to users and/or customers, but the value proposition and the resources that support it never stand alone because they need to be supported by other activities. The problem with contemporary frameworks for visualizing companies’ business models is that they often take the form of generic organization diagrams illustrating the process of transforming inputs to outputs in a chain-like fashion. A good example of this is found in the Integrated Reporting framework (IIRC, 2013) as well as in more management-oriented models such as the Business Model Canvas (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010). The core of the business model description should be focused on the connections between the different activities being performed in the company, in a reporting context often found as separated elements in the companies’ reports. Companies often report a lot of non-financial information (e.g. customer relations, distribution channels, employee competencies, knowledge sharing, innovation, and risks) but this information may seem unimportant if the company fails to show how the various elements of the value creation collaborate and change.

p.419

This is where the IC perspective becomes imperative. Current perceptions of relationships and linkages often reflect only tangible transactions (i.e. the flow of products, services, or money). However, in analysing the value transactions inside organizations (intra-organizational) and between an organization and its partners (inter-organizational), there is a tendency to forget the often-parallel intangible transactions and interrelations that are taking place (Montemari and Nielsen, 2013). Our hypothesis is therefore that no organization, regardless of the type of business model being leveraged, can function without the appropriate IC to make use of machinery, increase financial capital, conduct processes, management actions, and so on. An organization’s value drivers are always its IC.

Business models and configuring value

The concept of the business model offers a novel perspective from which to understand how companies become profitable, efficient, competitive, and sustainable: the latter being interpreted as the ability to survive in the long term. Much current focus in the field of business models concerns definitions, delimitations, and constructing frameworks for analysing business models (Wirtz et al., 2016a) or innovating them (Wirtz et al., 2016b; Foss and Saebi, 2017). Despite lacking unified theoretical groundings, at least according to Zott et al. (2011), many of these frameworks, ontologies, or models have proven to be successful in business and entrepreneurship practices. The most notable example of this is the Business Model Canvas published in Osterwalder and Pigneur’s 2010 book, Business Model Generation, which has sold over 1,200,000 copies to date and been translated into over 30 languages. In its wake, several other tools and frameworks have been developed that perform additional and complementary analyses to that of the Business Model Canvas, for example, the Value Proposition Canvas (Osterwalder et al., 2014) and the Kickass Company concept (Brøndum et al., 2015; Nielsen et al., 2016).

For a given company, it is important to be aware of the business model being applied for two reasons. First, the business model is the platform for executing corporate strategy. Therefore, if the business model is poorly configured or implemented, then the company will have difficulties in carrying through the strategy and ultimately then also meeting its non-financial and financial targets. Second, the business model affects the managerial processes of the organization because it directs the focus of how the firm does business. If the business model of a given firm relies on close ties with customers and the continuous involvement of strategic partners, then the managerial focus is expected to differ drastically from a situation where all customer interaction is web-based and all functions are in-house. In a similar manner, Mintzberg and Van Der Heyden (1999) argue that different forms of organization, or value configurations, carry different managerial foci, because the basis of value creation is different.

Positioning the business model

Baden-Fuller and Morgan (2010) argue that business models are distinct ways of doing business that can be distinguished from alternative modes of doing business and furthermore can be classified by the nature of how they are configured. Baden-Fuller and Morgan (2010) argue that a business model may be described as a model of how the firm does business. Sometimes the naming of the specific business model is done through the example of a well-known company. Five good examples of this are the business models of eBay, Dell, Ryanair, Gillette, and Skype. However, as Baden-Fuller and Morgan (2010, p. 157) note, behind most specific business model examples, the role models, there are scale models that “offer representations or short-hand descriptions of things that are in the world, while role models offer ideal cases to be admired”. For the above examples, these would be the e-auction business model configuration (eBay), the disintermediation business model configuration (Dell), the no-frills business model configuration (Ryanair), the razors and blades business model configuration (Gillette), and the freemium business model configuration (Skype). A commonly applied business model definition that captures these notions of configuring a business is Osterwalder and Pigneur’s (2010, p. 14): “A business model describes the rationale of how an organization creates, delivers, and captures value”. Later in this chapter we apply these five cases to illustrate that IC is the key value driver of the value creation of a business model.

p.420

Notions of value

The notion of value is important, because value creation is at the heart of understanding business models and this concept seems to introduce a new level of analysis, different from, but related to, strategy, organization, and management. Akin to tribalism, there are many opposing views on what the term ‘value’ signifies. In accounting, the debate between cash-based and accruals-based accounting exists and in strategy there is the debate between Porter’s (1985) market-based view and Barney’s (1991) resource-based view. Another problem is that ‘value’ is used as a catch-all term focused on value for the consumer and wealth for the organization, which might be problematic. Typically, value is treated as an outcome of business activity (Conner, 1991) and, furthermore, Sirmon et al. (2007) argue that there is minimal theory explaining ‘how’ managers/firms transform resources to create value. Hence value is not only poorly defined but also poorly theorized.

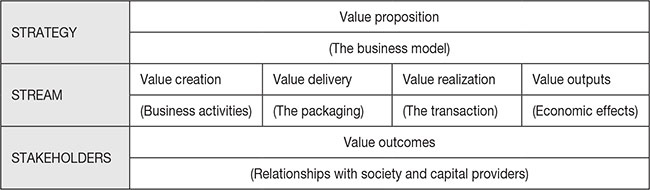

Figure 26.1 Conceptualizations of value

A way of resolving this confusion is to distinguish between ‘use value’ and ‘exchange value’. Use value is the benefit received from resources and capabilities and exchange value is the money that changes hands when resources, products, or services are traded (Bowman and Ambrosini, 2000). Figure 26.1 conceptualizes the relationships between concepts of value according to whether they are related to strategy, activities, or the stakeholders affected by the organization. Central to the business model literature is the term ‘value proposition’, which expresses the characteristics of the offering that the customer favours; hence it has close resemblance to the term ‘use value’ applied in resource-based theory. The value proposition is an expression of uniqueness and differentiation of a product or service.

p.421

Another important value concept in the field of business models is that of ‘value creation’. From a business model perspective, value creation expresses the business activities being performed and is closely related to ‘value-added’ (i.e. what extra value does the product/service have when it appears from the production process). An alternative way of understanding value creation is as cash flows, which are the ultimate liquidity (cash-based) effects of activities performed. Cash flows may differ despite identical activities due to the company’s position and strength in the value chain. However, it can be argued that higher cash flows are a proxy of the strength and resilience of the business model. Beyond value creation comes the actual physical interaction between the company and its customers in the form of the delivery of value. Here the packaging of the product is the subject of analysis. This relates not only to the delivery channel but also to the combination of product, service, knowledge, and financing included in the delivery.

The notion of ‘value realization’ refers to the effects of physical and monetary transactions between the company and its customers. Through transactions, the company’s activities are transformed into cash and from this converted into profits or losses depending on the company’s ability to manage its activities and finances. From the business model perspective, value realization is merely an element of the mode of competition. As such, value realization leads to value outputs, which are the effects on the total value of the company, in terms of the balance sheet and market value. There is an important distinction between shareholder value and value to the customer. The IIRC (2013) introduced the idea of ‘value outcomes’ to represent a broader notion of corporate effects, for example on the total set of stakeholders and also the way the company affects users, customers, partners, and networks and vice versa. From this categorization of value, we can distinguish between different types of value drivers and thereby also gain a better understanding of different types of value drivers in relation to the business model.

The value drivers of business models

An important question to ask is: how do companies create value? In this chapter, we argue that in both for-profit and not-for-profit organizations it is only IC, for example in the form of knowledge of how to use resources, that drives value creation. The resources themselves create nothing. The notion of value drivers has been applied in a series of related fields to that of IC (e.g. Marr et al., 2004; Cuganesan, 2005; Carlucci and Schiuma, 2007), such as R&D (Pike et al., 2005), and customer relationship management (Richards and Jones, 2008). A business model is a description of an organization’s value drivers as a whole.

Here, a value driver refers to any factor that enhances the total value created by an organization (Montemari and Nielsen, 2013), which is, in turn, the value that can be delivered to the actors involved in the business model (Amit and Zott, 2001). Value has different characteristics and can be split into several sub-dimensions (Amit and Zott, 2001; Ulaga, 2003; Cuganesan, 2005). One way of categorizing different perceptions of value and linking this to value drivers is provided by Nielsen et al. (2017). Their study identifies 251 different value drivers and categorizes them according to Taran et al.’s (2016) five-dimensional framework: value proposition, value segment, value configuration, value network, and value capture.

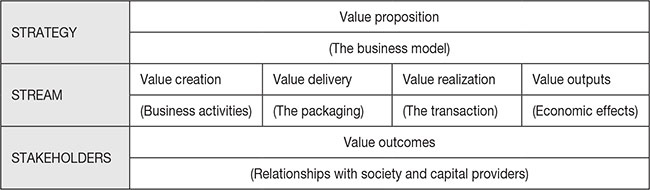

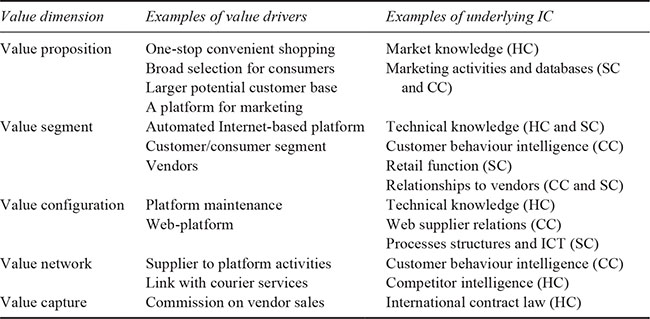

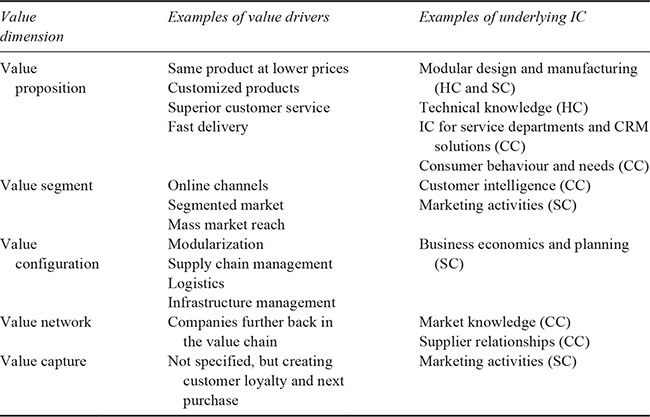

Table 26.1 illustrates how IC can be related to the different types of value drivers of business models according to Taran et al.’s (2016) five-dimensional framework. According to Nielsen et al. (2017), business models are representations of internal value drivers, the IC in the organization, and external value drivers, including relations to external partners. These are often interlinked, for example, the handling of external relationships, which is an important internal activity for many companies. IC can be in the form of relevant knowledge held by individuals employed in the organization or knowledge acquired from outside the organization for a specific functional purpose. For example, the value dimension ‘value proposition’ in Table 26.1, where ‘accessibility’ is a value driver. Behind the value driver ‘accessibility’ is knowledge about the customer’s preferred mechanisms of buying and receiving the company’s products, as well as logistics planning, but in addition to this, externally acquired knowledge relating to setting up the distribution platform. In many cases, companies have strategic partners running their distribution networks, and hence IC relating coordination with distribution partners also becomes relevant.

p.422

Table 26.1 Value dimensions, value drivers, and intellectual capital

IC and value creation measures

p.423

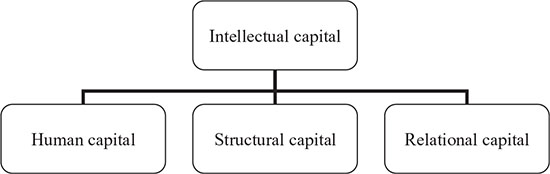

The typical break-down of IC follows Edvinsson and Malone’s (1997) IC-tree that divides IC into human capital, structural capital, and relational capital. Together with Edvinsson’s (1997) Skandia Navigator, this proposed disaggregation of IC can be perceived as a standard method of categorizing IC (Stewart, 1997; Sveiby, 1997; Meritum, 2002). Human capital is viewed as everything the company cannot own, and structural capital is defined as “everything left at the office when the employees go home . . . Unlike human capital, structural capital can be owned and thereby traded” (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997, p. 11). Ultimately the creation of value comes from activities being performed by the company. All activities in an organization and all activities outside the organization involving inputs and outputs to and from the organization can be characterized as being economic activities, and all of these activities are controlled by structural IC in one form or another. Last, is the category of relational capital, which concerns the value embedded in supplier relations, customer relations, and strategic partnerships. Figure 26.2 illustrates the three subclasses of IC most commonly applied.

Figure 26.2 The three generic classes of intellectual capital (adapted from Edvinsson and Malone, 1997)

Nielsen and Dane-Nielsen (2010) critique this type of disaggregation, arguing that the summing up between subclasses in an accounting-like fashion completely ignores the fact that IC has different characteristics according to the levels of organization at which they are present. In similar fashion, Mouritsen and Larsen (2005) argue that it is the entanglement of the depicted subclasses of IC that creates value and not the subclasses by themselves. The mechanism by which IC is enacted is through the organization of activities, in a business model, in which the knowledge of the individual is utilized. This leads to the proposition that the value drivers in an organization are always IC, and nothing else, because all economic activities are controlled by people who, ideally, have the necessary knowledge in order to manage or perform the activities.

IC properties at different levels of the organization

We use the notion of ‘emergentism’ (Emmeche et al., 1999) in the description of IC at the different levels of organization. Emergentism conceptualizes IC as represented throughout the organization by ‘emergent entities’ as ‘emergent properties’ (Nielsen and Dane-Nielsen, 2010) at different levels in the organization. Here, emergent entities are the carriers of the properties that create value and the properties of IC differ across levels of organization (Nielsen and Dane-Nielsen, 2010), both when a property has relations to a higher or a lower level of organization. In moving between different levels of the organization, completely different sets of properties emerge; in turn also affecting the units these are measured in (Wilson, 2015).

All activities relevant for the organization are performed in ‘functions’ with relations to other activities organized by the specific organizational structure, with emergent levels (Seibt, 2009). The propensity to form an emergent structure is, metaphorically speaking, the DNA of the organization. Within the notion of ‘mereology’, which is concerned with the study of parts and wholes, we find the notion of ‘emergentism’ (Stephan, 1999; Seibt, 2009), which originates from sociology (Sawyer, 2010) and biology (Kim, 1999; Potochnik, 2010), where scholars describe how natural phenomena and social communities result from a dominating hierarchical structure in nature (Rueger and McGivern, 2010).

It is important to emphasize that new emergent phenomena result in new entities (Emmeche et al., 1999), which are carriers of new emergent properties on a different form. For example, knowledge of the individual employees in different functional departments can work together to form structural capital in the form of processes and technologies containing data about products, customers, or markets. This notion of IC having different properties at different levels of the organization (Nielsen and Dane-Nielsen, 2010) is equivalent to the relationship between the role of organ systems in an organism, as described within the field of medicine (Potochnik, 2010). Hence, emergentism brings order to a field of random disorder (Rueger and McGivern, 2010), because disconnected components are ordered in a hierarchical system with functional levels.

p.424

We identify four levels of organization in order to discuss the value of IC. The first level is the individual level, where individual knowledge is expressed. In the second level, namely the group level, also known as functional departments, individuals are employed to perform tasks and here knowledge is a part of the functions and activities performed. The third level is the organizational level, which consists of a number of functional departments. The output from the organization is products or services. IC at the organizational level is embedded in the products and services. The fourth level is the market level and there are two markets. There is the market for products and services and then there is the market for companies, for example, the share market (the share value of the organization includes the value of IC within the company).

Activities create value for the organization, and activities at all different levels in the organization are driven by the knowledge of how to do things. It is not the stock of raw materials that creates value. It is not the machinery that creates value in the organization. It is the knowledge of how to use the machinery and sophisticated equipment and how to make use of the raw materials that is creating value. The stock of raw materials has no value in the warehouse as long as it just sits there. Only when used in the production of items, raw materials, or components, does the stock of materials become a means of value creation. The same goes for buildings, financing, machinery, equipment, and prepared marketing materials, and so on. These capitals are worth nothing without the knowledge of how to utilize them. IC used in activities is the driving force behind value creation, and knowledge of the organization’s products and service is necessary for this value creation.

Customers do not create organizational value per se. Rather, it is the knowledge of the customers, their wishes and requirements, and the knowledge of how to sell, which ultimately create value. Long-term contracts with customers also carry value. However, behind the contracts lies knowledge of the market, knowledge of laws and regulations, and so on. Thus, IC creates value when applied in activities in the organization itself and in the transactions with other organizations. In this sense, value drivers can be seen as effects of the application of IC in concrete activities. These activities can take place at different levels of the organization in accordance with the specific relevant functional departments and they will result in emergent effects.

Next step performance measures

Mouritsen et al. (2003b) propose a model to analyse the interrelations of IC across two dimensions. The first is the type of IC and the second is whether the IC concerns resources, activities, or effects. Together with an understanding of the organization’s strategy and the key management challenges facing the executive management, this model makes it possible to mobilize a series of questions to identify key IC indicators. Evaluating the effects of IC can therefore be done in a series of steps.

p.425

The first step is evaluating the identified indicators in a scorecard-like fashion in relation to a set of expected targets for each indicator. In a second step, the indicators can be evaluated in the analysis model (Mouritsen et al. 2003b) presented in Figure 26.3, by asking which indicators affect each other. Third, the analysis can be completed by asking whether some of the 12 boxes have missing indicators. Finally, with the indicators at hand, management should ask themselves how they fit into the story of what the company does and how it is unique. In this manner, management is gradually moving closer to understanding the effects of IC on the value creation of the organization. In order to assess if the composition, structure, and use of the company resources are appropriate, it is necessary to consider the development of the indicators over time, and finally the company may pursue relative and absolute measures for benchmarking across time and across competitors.

Unlike an accounting system, the analysis model is not an input/output model. There is no perception that any causal links between actions exist to develop employees and the effect in that area (e.g. increased employee satisfaction). The effect of such an action may appear as a customer effect. The employee becomes more qualified and capable of serving the customers better. The task of the analysis is thus to explain these ‘many-to-many relations’ in the model. The classification itself does not explain the relations, just as increased expenses for R&D alone do not lead to increased turnover in the financial accounting system.

It is essential to support a company’s business model story with performance measures. While it may be acceptable for some companies merely to state that one’s business model is based on mobilizing customer feedback in the innovation process, excellence would be achieved by explaining how this will be done, and even more demanding is proving the effort by indicating how many resources the company devotes to this effort, how active the company is in this matter, and whether it stays as focused on the matter as initially announced, and whether the effort has had any effect, for example, on customer satisfaction, innovation output, and so on. According to Bray (2010, p. 6):

[r]elevant KPIs measure progress towards the desired strategic outcomes and the performance of the business model. They comprise a balance of financial and non-financial measures across the whole business model. Accordingly, business reporting integrates strategic, financial and non-financial information, is future-performance focused, delivered in real time, and is fit for purpose.

From an accounting perspective, the question of how to capture value creation and value transactions when value creation to a large extent goes on in a network of organizations and not inside an organization, as traditionally perceived, is problematic. Also, from a management perspective, the question of how to produce decision-relevant information is seriously challenged by business model innovations and the advance of new types of business ecosystems, for example, based on crowd funding, social communities, virtual collaboration networks, and a competitive landscape based on business model ‘innovation-ability’.

p.426

Empirical examples of business models and IC

In this section, we introduce five examples that illustrate how IC becomes the value driver of different types of business models. We use Table 26.1 as a frame to illustrate how each business model has varying value drivers across the five dimensions introduced by Taran et al. (2016). Furthermore, precisely which IC lies behind those value drivers. In the articulation of the underlying IC behind the value drivers of each of the five dimensions, we note the sub-class of IC according to Edvinsson and Malone’s classification scheme (1997).

Example 1: eBay

Table 26.2 Analysis of the e-Mall business model configuration

eBay applies a business model configuration called ‘The Mall’, or ‘e-Mall’ configuration. It was initially coined by Timmers (1998) as a collection of shops or e-shops, usually enhanced by a common umbrella. The e-Mall is similar to a physical mall in that it consists of a collection of several shops – in this case web-shops. A closely related example to this way of doing business is the merchant model (Rappa, 2001), one-stop low-price shopping (Linder and Cantrell, 2000), and the shop in shop (Gassmann et al., 2014). Revenues are generated from membership fees to the platform, transaction fees, and advertising. The typical value proposition of this business model configuration is that the web-shops benefit from professional hosting facilities and thereby are able to lower their costs and the complexity of being on the Internet. Furthermore, suppliers and buyers enjoy the benefits of efficiency/time-savings, no need for physical transport until the deal has been established, and global sourcing.

p.427

Table 26.2 illustrates that this business model configuration requires IC across a broad array of the sub-dimensions. The success of eBay is in part driven by its ability to create critical mass and global presence. Therefore, the human capital relating to international contract law and the value proposition of convenience offered through the customer capital perspective might be the prime IC of this business model configuration.

Example 2: Dell

The business model configuration used by Dell is called disintermediation. It cuts out the middlemen by delivering the offering directly to the customer through its own retail outlets, sales force or Internet-based sales rather than through intermediary channels, such as distributors, wholesalers, retailers, agents, or brokers. Related ways of doing business are the direct manufacturing model (Rappa, 2001), direct to consumer model (Weill and Vitale, 2001), and direct selling (Gassmann et al., 2014). Dell has been successful by delivering directly to the customer a product or a service that had traditionally gone through an intermediary. By modularizing their product Dell allowed customers to choose varying configurations of the computers they ordered, thus creating a feeling of custom-made despite the prices generally beating the market. This was possible because of the cost savings from avoiding traditional intermediaries and because customers were prepared to buy at the website and wait for delivery instead of taking the computer home straight from the shop.

Table 26.3 illustrates that the success of this business model configuration revolves around minimizing the challenges created by the lack of physical store. Therefore, the IC behind the customer service, CRM, and the logistics becomes of vital importance. While the ability to minimize the challenges is based on customer capital, logistics and modular manufacturing are related mainly to structural capital.

Table 26.3 Analysis of the disintermediation business model configuration

p.428

Example 3: Ryanair

A typical low-cost airline, the Irish aviation company Ryanair applies the no-frills business model configuration (Gassmann et al., 2014; Taran et al., 2016). In this way of doing business, organizations offer a low-price, low service/product version of a traditionally high-end offering, in this case commercial aviation, consistent with Christensen and Overdorf’s (2000) characterization of disruption (see also Markides, 2006). Similar labels for this way of doing business have been termed ‘low touch’ (Johnson, 2010), ‘add-on’ (Gassmann et al., 2014), ‘low-price reliable commodity’ (Linder and Cantrell, 2002), and ‘standardization’ (Johnson, 2010). The key value driver, low prices for low service is the value proposition put forth by Ryanair. Hence, customers buy the basic offering cheap, and pay for add-ons in the product/service offering, for example, choice of seats, priority boarding, and baggage. A more in-depth account of Ryanair’s business model and partnering with hotels, car rental services, airport transportation, and bargaining power towards the, typically smaller, airports is offered by Casadesus-Masanell and Ricart (2010). In reality we might question who Ryanair’s most important customers are: the consumers or the airports? Ryanair achieves low costs at the smaller airports because it brings in high customer volumes and uses this as a bargaining tool.

Table 26.4 Analysis of the no-frills business model configuration

p.429

Table 26.5 Analysis of the bait and hook business model configuration

Table 26.4 illustrates the IC of the no-frills business model applied by Ryanair. For Ryanair, efficiency is important, therefore structural capital related to operating procedures becomes the prime IC behind the value drivers. However, in addition to this, the human capital related to negotiating with airports and other types of strategic partners, which ensures the conversion of critical mass in terms of customer numbers to lower costs, is imperative to the survival of this particular company.

Example 4: Gillette

Gillette is renowned for its use of the ‘bait and hook’ business model configuration (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010). In this configuration companies seek to provide customers with an attractive, inexpensive, or free initial offer that encourages continuing future purchases of related products or services. This is also a much-used tactic in the printer business, for example the HP inkjet. This business model configuration is also known as razors and blades (Linder and Cantrell, 2000; Johnson, 2010; Gassmann et al., 2014) or lock-in (Gassmann et al., 2014). The key of this configuration is the close link between the inexpensive or free initial offer and the follow-up items on which the company earns a high margin as well as related product/service accessories. The key value driver is the achievement of lock-in and thereby also continued revenue streams.

Table 26.5 illustrates that this particular way of doing business relies heavily on customer capital and structural capital. The key to success for Gillette is the global presence of consistent and high-quality products, and the ability to protect the brand and the intellectual property. Procter & Gamble, which owns the Gillette series, is able to accomplish this because of its sheer size. Global presence, coupled with the lock-in mechanism of the business model, ensures that customers can turn their purchase of shaving equipment into a habit, regardless of where they are in the world.

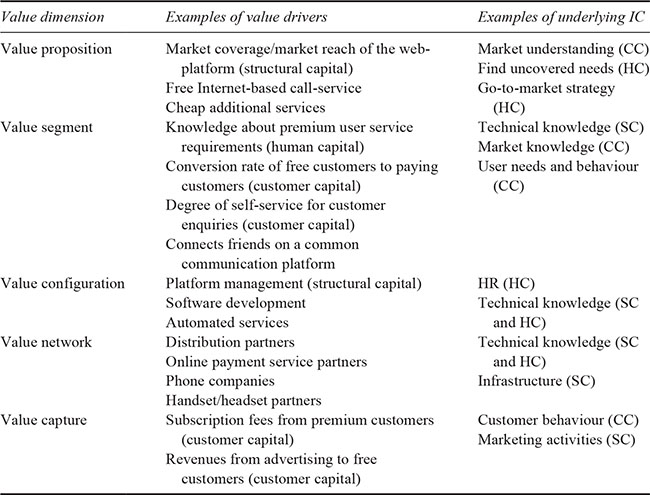

Example 5: Skype

Skype applies a freemium business model configuration. The term freemium was first coined by Anderson (2009) and is in essence a business model that utilizes two types of customer segments. One segment is interested in a basic service for free, while the second, premium segment, is willing to pay for a more advanced product partly because the freemium segment provides critical mass to the business model. This way of doing business has similarities with the inside-out and no-frills business model configurations. The inside-out business model configuration (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010) is used by companies that sell their own developed R&D (i.e. intellectual properties or technologies that are under-used inside the company).

p.430

Table 26.6 Analysis of the freemium business model configuration

Table 26.6 shows that the structural capital of Skype is important to the functioning of the platform service and that the human capital that came up with the idea was central. However, it also illustrates that the notion of the double-sided platform of free and premium customer segments in the form of customer capital is vital for the success of Skype. This is because the most important aspect of the success is the ability to create the critical mass that allows the freemium model to flourish. It was clearly the human capital that formulated the go-to-market strategy that turned Skype into the company it is today. The market traction created by the founders ensured that Skype became synonymous with making phone calls over the Internet, best exemplified by the expression: “Let’s Skype!”

Discussion and conclusions

This chapter argues that IC is the platform of any business model and its value creation, and that without IC there is no value creation. The examples applied above illustrate the relationship between each of these distinct business model configurations, their respective value drivers, and the IC elements that drive them.

These examples from five distinct business model configurations also illustrate that the value drivers of business models are IC entities at different levels of the organization. Individuals have relevant knowledge and work with other staff members in functional departments. An organization is made up of a number of interacting functional groups and departments, which together form the whole organization. Organizations, suppliers, and buyers act in a market and the price and volume of products are ultimately determined by so-called market forces. All of these are the results of an emergent process. Through the organization, right from the individual employee to the market level novel properties emerge at each level with new dimensions of IC. Hence, this chapter provides case study evidence to support the arguments of Nielsen and Dane-Nielsen (2010). Interaction and communication between individuals creates the output of the work done in the functional departments. Further, cooperation between the necessary functional departments and groups will create the final output of the organization that is valued by customers because it does a job for which they are willing to pay (Osterwalder et al., 2014). However, the final monetary value of the output from an organization is determined by the market in which the organization is operating.

p.431

This ‘emergentist’ perspective is a research perspective that can be applied to many fields of research. For example, the notion of emergentism is used as a research perspective within biology and medicine (Kim, 1999) and also within philosophy (Potochnik, 2010). Emergentism is a discipline within mereology, the study of parts and wholes (Seibt, 2009). Emergent phenomena within the social space have been studied within sociology since the 1920s (Sawyer, 2010). This perspective argues that people, for example employees, act collectively to create new phenomena as collective knowledge and collective action that individuals do not hold by themselves. This is the foundation for claiming that IC at higher levels in a hierarchical structure, for example an organization, is different from the knowledge held by individual staff members in the organization. In doing so, this chapter offers a theoretically grounded lens for analysing and understanding business models by combining the perspectives of IC and emergentism from Nielsen and Dane-Nielsen (2010).

Also our analyses uncover several relevant action points for future studies that should be undertaken in order to further our understanding of IC in action, as well as of business models. This raises the question of the relationship between business models and different levels of the organization. Certainly, in our examples, we see that these business model configurations combine IC on several levels of the organization. But is this always the case? And can we talk of business models as organizational models or business models on an industry level? Furthermore, we find relevant connections between the prevailing understanding of business models based on certain value propositions to customers and the market level of our emergentist perspective. Here there is a fruitful avenue to follow in combining business models and market perspectives, for example, by viewing suppliers and buyers as non-managed organizations and markets as informal institutions.

A practical contribution of this chapter, besides the inspiration for managers of how to relate IC to the value drivers of specific business model configurations (Nielsen et al., 2017), is that business models as managerial concepts might serve different purposes. Once the management team of a company has determined which is the business model configuration with which they are competing, this information can be used for multiple purposes. One such purpose is a managerial agenda. It entails managing, leading, and controlling the organization and establishing relationships with key strategic partners. Another purpose is communication. Here a wide array of potential stakeholders comes into play, including investors, employees, municipalities, customers, and strategic partners, and the notions of business models have proven themselves successful for aligning the views among such stakeholder groups on how the company works. Finally, there is also the business development purpose, also denoted as business model innovation. This perspective has received much attention from entrepreneurs in recent years, but has also entered into the established business sector and the academic curriculum.

p.432

The responsibility for managing, communicating, and innovating firms and their business models ultimately lies with the management team and the board of directors, while the use of the resulting analyses should be applicable to the whole organization. The application of business models may have implications on multiple time-horizons. In the short term, the notions of business models can help to evaluate the efficiency with which a company engages with customers. In the medium term, business models help companies to decipher whether customers are willing to pay for delivered value and how well the company utilizes strategic partners. On a more long-term basis, business models can help companies understand how to improve their overall concept for making money. Finally, it is evident that business models can serve a number of different managerial agendas. As seen above, business models might be concerned with managing, controlling, and making the organization efficient. However, business models might also serve purposes of managerial sensemaking in an innovation perspective (Michea, 2016), or open up new entrepreneurial possibilities (Lund and Nielsen, 2014).

References

Amit, R. and Zott, C. (2001), “Value creation in e-business”, Strategic Management Journal, Vol. 22, Nos 6–7, pp. 493–520.

Anderson, C. (2009), Free: The Future of a Radical Price, Random House, New York.

Baden-Fuller, C. and Morgan, M. (2010), “Business models as models”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, Nos 2–3, pp. 156–171.

Barney, J. B. (1991), “Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage”, Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 99–121.

Bowman, C. and Ambrosini, V. (2000), “Value creation versus value capture: Towards a coherent definition of value in strategy”, British Journal of Management, Vol. 11, No. 1, pp. 1–16.

Bray, M. (2010), The Journey to Better Business Reporting: Moving beyond Financial Reporting to Improve Investment Decision Making, KPMG, Sydney, Australia.

Brøndum, K., Nielsen, C., Tange, K., Laursen, F., and Oehlenschläger, J. (2015), “Kickass companies: Leveraging business models with great leadership”, Journal of Business Models, Vol. 3, No. 1, pp. 22–28.

Carlucci, D. and Schiuma, G. (2007), “Knowledge assets value creation map: Assessing knowledge assets value drivers using AHP”, Expert Systems with Applications, Vol. 7, pp. 814–822.

Casadesus-Masanell, R. and Ricart, J. E. (2010), “From strategy to business models and onto tactics”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, No. 2, pp. 195–215.

Christensen, C. M. and Overdorf, M. (2000), “Meeting the challenge of disruptive change”, Harvard Business Review, Vol. 78, No. 2, pp. 66–77.

Conner, K. R. (1991), “A historical comparison of resource-based theory and five schools of thought within industrial organization economics: Do we have a new theory of the firm?” Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 121–155.

Cuganesan, S. (2005), “Intellectual capital-in-action and value creation: A case study of knowledge transformation in an innovation process”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 6, No. 3, pp. 357–373.

Edvinsson, L. (1997), “Developing intellectual capital at Skandia”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 366–373.

Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M. S. (1997), Intellectual Capital, Piatkus, London.

Emmeche, C., Køppe S., and Stjernfelt F. (1999), “Explaining emergence”, Journal for General Philosophy of Science, Vol. 28, pp. 83–119.

Foss, N. J. and Saebi, T. (2017), “Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go?” Journal of Management, Vol. 43, No. 1, pp. 200–227.

p.433

Gassmann, H., Frankenberger, K., and Csik, M. (2014), The Business Model Navigator, Pearson Education Limited, Harlow, UK.

IIRC (2013), The International <IR> Framework, International Integrated Reporting Council, London, available at: www.theiirc.org.

Johnson, M. W. (2010), Seizing the White Space: Business Model Innovation for Growth and Renewal, Harvard Business Press, Brighton, MA.

Kim, J. (1999), “Making sense of emergence”, Philosophical Studies, Vol. 95, pp. 3–36.

Linder, J. and Cantrell, S. (2000), Changing Business Models: Surfing the Landscape, Accenture Institute for Strategic Change, Cambridge, MA.

Linder, J. and Cantrell, S. (2002), “What makes a good business model anyway? Can yours stand the test of change?”, Outlook, available at: www.accenture.com.

Lund, M. and Nielsen, C. (2014), “The evolution of network-based business models illustrated through the case study of an entrepreneurship project”, The Journal of Business Models, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 105–121.

Markides, C. (2006), “Disruptive innovation: In need of better theory”, Journal of Product Innovation Management, Vol. 23, No. 1, pp. 19–25.

Marr, B., Schiuma, G., and Neely, A. (2004), “The dynamics of value creation: Mapping your intellectual performance drivers”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 312–325.

Meritum (2002), Measuring Intangibles to Understand and Improve Innovation Management, European Commission, Brussels.

Michea, A. (2016), Enacting Business Models, PhD dissertation, Copenhagen Business School.

Mintzberg, H. and Van der Heyden, L. (1999), “Organigraphs: Drawing how companies really work”, Harvard Business Review, September-October, pp. 87–94.

Montemari, M. and Nielsen, C. (2013), “The role of causal maps in intellectual capital measurement and management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 4, pp. 522–546.

Mouritsen, J. and Larsen, H. T. (2005), “The 2nd wave of knowledge management: The management control of knowledge resources through intellectual capital information”, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 16, No. 3, pp. 371–394.

Mouritsen, J., Bukh, P. N., Johansen, M. R., Larsen, H. T., Nielsen, C., Haisler, J., and Stakemann, B. (2003b), Analysing Intellectual Capital Statements, Danish Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation, Copenhagen, available at: www.vtu.dk/icaccounts.

Nielsen, C. (2011), “When intellectual capital drives the business model, then”, in Lloyd, A. and Reddy, M. (Eds), Human Capital Handbook, Hubcap-Digital, Hockliffe, UK, pp. 26–31.

Nielsen, C. and Dane-Nielsen, H. (2010), ”The emergent properties of intellectual capital: A conceptual offering”, Journal of Human Resource Costing & Accounting, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 6–27.

Nielsen, C., Lund, M., and Thomsen, P. (2017), “Killing the balanced scorecard to improve internal disclosure”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 45–62.

Nielsen, C., Roslender, R., and Schaper, S. (2016), “Continuities in the use of the intellectual capital statement approach: Elements of an institutional theory analysis”, Accounting Forum, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 16–28.

Osterwalder, A. and Pigneur, Y. (2010), Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Osterwalder, A., Pigneur, Y., Bernarda, G., and Smith, A. (2014), Value Proposition Design: How to Create Products and Services Customers Want, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken, NJ.

Pike, S., Roos, G., and Marr, B. (2005), “Strategic management of intangible assets and value drivers in R&D organizations”, R&D Management, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 111–124.

Porter, M. E. (1985), Competitive Advantage, The Free Press, New York.

Potochnik, A. (2010), “Levels of explanation reconceived”, Philosophy of Science, Vol. 77, No. 1, pp. 59–72.

Rappa, M. (2001), Managing the Digital Enterprise: Business Models on the Web, North Carolina State University, available at: http://digitalenterprise.org/models/models.html (accessed September 2015).

Richards, K. A. and Jones, E. (2008), “Customer relationship management: Finding value drivers”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 120–130.

Rueger, A. and McGivern, P. (2010), “Hierarchies and levels of reality”, Synthese, Vol. 176, pp. 379–397.

p.434

Sawyer, R. K. (2010), “Emergence in sociology: Contemporary philosophy of mind and some implications for sociological theory”, American Journal of Sociology, Vol. 107, No. 3, pp. 551–585.

Seibt, J. (2009), “Forms of emergent interaction in general process theory”, Synthese, February, pp. 166–479.

Sirmon, D., Hitt, M., and Ireland, R. D. (2007), “Managing firm resources in dynamic environments to create value: Looking inside the black box”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 32, No. 1, pp. 273–292.

Stephan, A. (1999), “Varieties of emergentism”, Evolution and Cognition, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 49–59.

Stewart, T. A. (1997), Intellectual Capital, Nicolas Brealey Publishing, London.

Sveiby K. E. (1997), The New Organizational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Knowledge-Based Assets, Berrett-Koehler, San Francisco, CA.

Taran, Y., Nielsen, C., Thomsen, P., Montemari, M., and Paolone, F. (2016), “Business model configurations: A five-V framework to map out potential innovation routes”, European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 492–527.

Timmers, P. (1998), “Business models for electronic markets”, Journal on Electronic Markets, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 3–8.

Ulaga, W. (2003), “Capturing value creation in business relationships: A customer perspective”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 32, No. 8, pp. 677–693.

Weill, P. and Vitale, M. R. (2001), Place to Space, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Wilson, J. (2015), “Metaphysical emergence: Weak and strong”, in Bigaj, T. and Wüthrich, C. (Eds), Metaphysics in Contemporary Physics, Brill, Leiden, Netherlands.

Wirtz, B. W., Göttel, V., and Daiser, P. (2016b), “Business model innovation: Development, concept and future research directions”, Journal of Business Models, Vol. 4, No. 2, pp. 1–28.

Wirtz, B. W., Pistoia, A., Ullrich, S., and Göttel, V. (2016a), “Business models: Origin, development and future research perspectives”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 49, No. 1, pp. 36–54.

Zott, C., Amit, R., and Massa, L. (2011), “The business model: Recent developments and future research”, Journal of Management, Vol. 37, No. 4, pp. 1019–1042.