Figure 27.1 Stakeholder foci change over time

p.435

MAKING INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL MATTER TO THE INVESTMENT COMMUNITY

Morten Lund and Christian Nielsen

Introduction

Critics of intellectual capital (IC) argue that information of this sort is irrelevant to the investment community. This could be because the IC information is brought to the market in formats that are not timely (Dumay, 2016), or because the stakeholders in the investment community do not understand IC information (Holland and Johanson, 2003). On the other hand, studies have shown that the investment community in certain instances, such as Initial Public Offerings, actually does apply IC information (Bukh et al., 2005; Nielsen et al., 2006), but that during recurring valuations this information is contained elsewhere in the market for information than in official documents such as analyst reports (Nielsen, 2008). One avenue for improving the relevance of IC information is to create a stronger link to the future value creation scenarios of the given company through the concept of business models, which will illustrate the explicit interconnectedness of the value creating activities of the company. In another chapter in this companion, Dane-Nielsen and Nielsen (2017) argue that IC constitutes the only true value drivers of any business model.

Since the late 1990s, standard-setting bodies and academics have been discussing how to improve the informativeness of IC reporting and narrative reporting (e.g. in the form of management commentary, and lately this is reflected in the debate around Integrated Reporting). Over this period, which types of users such reporting is to be aimed at, and in turn, the perceptions of its possible content, have been the focus of a range of studies. Since the turn of the millennium, such new types of reporting have been addressing the needs of a much broader set of stakeholders than has financial reporting traditionally.

Lately, integrated reporting (<IR>) has become a dominant discourse in the business reporting debate, and has attracted significant attention within the academic research literature (De Villiers et al., 2014), the global accountancy profession, and practitioner communities (Dumay et al., 2016). <IR> places the concept of business models at the heart of organizing information and key performance indicators, and highlights investors as the main stakeholders (Roslender and Nielsen, 2017). This is consistent with the normative view of an organization’s purpose, namely to generate profits, but is in conflict with the social and environmental discourse, despite its notable presence in the <IR> framework (Dumay, 2016).

p.436

The social and environmental discourse, like that of IC, is much more aligned with March and Olsen’s (1989) logic of the appropriateness perspective, where corporate actions are concerned with communicating core values, mission statements, the business concept, political ideology, and social responsibility (Söderbaum, 2002, p. 191). Historically, the consequence of this is that the specific needs of professional users, such as private and institutional investors and financial analysts, have been downplayed somewhat in the business reporting debate. Some would go so far as to say that the investment community is rarely heard in these respects (PWC, 2007, p. 3). However, in 2009, the IASB released its IFRS Practice Statement on Management Commentary (IASB, 2009), specifically emphasizing existing and potential capital providers as the primary users of financial reporting and thereby also management commentary (IASB, 2009, p. 8). This emphasis is echoed by Bray (2010), who states that the social and environmental reporting movement is taking steps in the direction of attaining relevance towards the capital markets and that early adopters of such disclosures potentially could help build impetus for later regulation. The <IR> framework is a first serious attempt at providing a distinct business reporting focus to the investment community.

Since the Jenkins Report (AICPA, 1994), there has been extensive discussions about which information companies ought to disclose and whether financial reporting as we know it today conveys sufficient relevant information to the capital markets. Research relating to the agenda of management commentary has focused on which types of information companies are disclosing voluntarily in their annual reports (Beattie and Pratt, 2002; Vanstraelen et al., 2003) or via their corporate websites (Fisher et al., 2004), and which firm characteristics are influential on the extent of voluntary disclosure (Cooke, 1989; Adrem, 1999).

However, information flows from companies to the financial markets and other stakeholder groups are much more complex than those conveyed through historical financial statements (Dumay, 2016). Among the information channels that companies apply as disclosure channels are press and stock market releases, corporate newsletters, profiles and brochures, corporate websites, conference calls, the press, face-to-face meetings with stakeholders and investors, and social media. This leads to several challenges for companies as well as external stakeholders. First, from the company perspective, it is a question of ensuring connectivity between the various media and that the message is aligned across these. Second, from the stakeholder perspective, it is a question of always being up to date on what is happening in the company, which may entail following a number of different information channels.

Third, information flows from companies have become much more accessible to both private and professional stakeholders in the last decade through the rise of the internet and ubiquitous access to it through wi-fi connections and smartphones. At the same time, the complexity and amount of information have risen to unprecedented levels, making it more and more difficult for the ‘ordinary’ investor to calculate the consequences of such information and thereby also the actions of the companies in which they wish to invest.

Fourth, another challenge is approaches of communicating strategy and the business model (Bray, 2010). <IR> specifically uses the terminology of business models as an organizing element in its framework. However, this is done in a value chain-like fashion, as noted by Tweedie et al. (forthcoming). Contemporary companies are competitive due to their extremely complex structures and their ingenious ways of retracting value from networks of resources. Contemporary companies are not organized in the silos described in basic textbooks of organization (i.e. in simple value chains). However, when one reads the narrative sections of the same companies’ financial reports, this could well be the impression one gets. The narrative sections of the financial annual report are therefore typically not aligned with the actual value creation setup of the company (Mintzberg and Van Der Heyden, 1999) and this might help to explain why professional users of financial reporting need to have additional information channels.

p.437

Therefore, we argue that management commentary needs to a much greater extent to illustrate the explicit interconnectedness between the value creating activities of the company. In other words, the narrative sections need to be aligned with the logic of the business model, thereby describing the specific structures and strategies of value creation, which are not always in the form of a value chain.

It has been suggested that a potential step in this direction could be to introduce the notion of industry specific value creating interrelations. In relation to this, the World Intellectual Capital Initiative (WICI, 2010, 2016) has been working on creating a set of industry-based KPI sets for its business reporting framework. Such industry taxonomies may be a good starting point as they can induce companies to start thinking in terms of what are their key value creating processes, activities, and partnerships. However, Nielsen et al. (2017a) argue that companies in the same industry can be immensely different (i.e. have different business models, and organizational and legal structures), and therefore it does not make sense to develop standards for either length or content of the management commentary. Therefore, such industry taxonomies might only be expected to be a part of the initialization of these developments where using the structure of business models is a fruitful avenue to pursue.

Conforming to users’ needs, but which users?

Since the late 1990s, a myriad of reports and guidelines have addressed the value of IC reporting, business reporting, and management commentary narratives. Critics have questioned the ability of the more traditional reporting vehicles, such as annual reporting (Lev, 2001), but also voluntary and standalone IC reports (Dumay, 2016) and the contemporary <IR> (Dumay et al., 2016) in presenting meaningful disclosures regarding IC and value creation. This section explores how business reporting may conform to users’ needs by asking the critical question: Who are the users of business reporting?

It is important to consider who are the target stakeholders of a report. For example, Bray (2010) states that the most important user of business reporting is the investor. Similarly, Beattie and Pratt (2002) argue that the type of disclosures contained in the narrative sections of the financial report are important to investors and to analysts as these users base their earnings and cash flow expectations on both financial and non-financial information. This is because earnings and cash flow expectations are considered cornerstones in company valuation and non-financial information contributes to the accuracy of the valuation (Lang and Lundholm, 1993; Christensen and Demski, 2003). More informative disclosures and more explanation will thus reduce the information asymmetry between the company and the capital markets, thereby diminishing uncertainty regarding the company’s future prospects (Botosan, 1997) and lead to more accurate forecasts on which investors can base their investment decisions (Lang and Lundholm, 1996).

In addition, Vanstraelen et al. (2003) find that higher levels of non-financial disclosures are associated with lower dispersion and higher accuracy of financial analysts’ earnings forecasts. These arguments therefore illustrate that providing voluntary information (e.g. through IC reports) is a way of satisfying users’ needs (McEwen and Hunton, 1999). The question then prevails whether the reporting vehicles of today, like IC reports and <IR> can fulfil these needs. Holman (2002) states that comprehensive business reporting should convey a broader representation of the company and its value creation logic than that communicated through financial reporting as it is practised today.

p.438

However, this notion of considering and researching the usefulness of annual reporting from a user perspective is not new. Lee and Tweedie’s studies (1977, 1981) examined first the private investors’ and second the institutional investors’ perceptions of the usefulness of the corporate report. Arnold and Moizer (1984) and Pike et al. (1993) subsequently studied user requirements from the analyst’s perspective. Bartlett and Chandler (1997) conducted a follow-up study of Lee and Tweedie’s 1977 study, concluding that little had changed in those 20 years despite the efforts of the accounting profession and the business community to improve communication between management and shareholders.

Figure 27.1 is an illustration of the fact that the stakeholder focus in business reporting has not followed that of the surrounding business environment. For many years there was a much broader perception of relevant stakeholders in the business reporting literature than applied in practice. Starting out, the Jenkins Report (AICPA, 1994) had a rather narrow conception of relevant stakeholders, stating that the target users of business reporting were investors and financial analysts. Around the turn of the millennium, a much broader perception of relevant stakeholders was communicated in the literature. This was mirrored in the then flourishing IC reporting practices (Nielsen et al., 2017b), but also in the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI, 2002) and the work by the World Business Council for Sustainable Development (Heemskerk et al., 2003). However, recent developments have seen a contention of the broader stakeholder focus in the literature (IASB, 2009; Bray, 2010; IIRC, 2013a).

In the same timeframe, the stakeholder focus in businesses’ actual business reporting practices have continually broadened, but without the late contraction as seen in the literature. The early 1990s saw the emergence of several management models, such as the Balanced Scorecard and Business Excellence, these having broader foci on customers and employees and not just investors. Around the turn of the millennium, with the advent of the concepts of the knowledge society and the new economy, this stakeholder perspective had broadened somewhat, and this has been driven further by the social and environmental accounting practices and focus on corporate governance in the wake of the financial crisis.

Figure 27.1 Stakeholder foci change over time

Although there is a great deal of agreement concerning the need for developments in corporate reporting practices, there is some ambivalence as to how this should be carried out. While some contributions argue that standard setters should be responsible for developing comprehensive models for business reporting (AICPA, 1994), others reason that changes must come from the business community (Bray, 2002, p. 3). The problem is that non-financial information is inherently idiosyncratic to particular industries (Upton, 2001) and also to individual firms because it varies with the applied business models (Nielsen et al., 2017a). Therefore, it is not necessarily new accounting standards that are needed, rather standards for form, presentation, and disclosure of underlying assumptions, as suggested by DiPiazza and Eccles (2002).

p.439

The reasons advocated for improving companies’ business reporting efforts relate to both external and internal objectives. Externally, relevance to the capital market is perceived as a main driver of business reporting, as the underlying premise that improving disclosure makes the capital allocation process more efficient and reduces the average cost of capital. FASB (2001) provides a number of concrete examples with helpful ideas to companies on how to describe and explain their investment potential to investors. Also, it is argued that a new generation of analytical tools is needed to enable company boards, shareholders, and investors to judge management performance and differentiate good, bad, and delinquent corporate stewardship (Eustace, 2001, p. 7). Moreover, Blair and Wallman (2001, p. 45) accentuate that more reliable and useful information to financial markets must be obtained by improving internal measurement, which creates a better understanding of the company’s key value drivers.

Therefore, internal and external objectives become closely interrelated. Blair and Wallman (2001, p. 58) argue that:

[t]he lack of good information about the most important value drivers in individual firms, and in the economy as a whole, makes it more difficult for managers within firms and individual investors in the capital markets to make sensible resource allocation decisions.

Also of internal relevance is the ability to communicate strategy, vision, and corporate objectives to employees throughout the firm. According to Bray (2002), enabling management and employees to understand the reporting and communication strategy of the company can be achieved by synchronizing the company’s performance reporting with management’s decision-making models.

Critics of management narratives, business reporting, and voluntary disclosures (Lev, 2001; Gu and Li, 2007) argue that the reliability of the information is questionable and that even if reliability was to be obtained through regulation or consistency of disclosures, there would still be the problems of the subjectivity of management and the shelf-life of the narratives. Creating confidence in non-financial information can be achieved through consistent practices (PWC, 2007), thereby generating user experience in understanding such performance measures, rather than creating prescriptive standards for these types of information. An underlying notion within the business reporting debate is that mandatory requirements are not satisfactory in order to meet users’ needs and that the future of corporate reporting includes aspects currently perceived as voluntary (DiPiazza and Eccles, 2002). Eccles et al. (2001) argue that the implications of this will be moving companies’ practices from a performance measurement agenda to a performance reporting agenda. In summary, if non-financial information is important for the management of the company, then it is also relevant for the investment community because it provides context for the financial numbers.

Creating comparable non-financial information is argued to be a means of increasing the reliability of key performance indicators (Nielsen et al., 2006), like those that are presented in management commentary sections of annual reports (Blair and Wallman, 2001) or <IR>. Comparability can be thought of in two ways. First, it can relate to the ability to track non-financial information from period to period (FASB, 2001; Upton, 2001). Second, it can relate to the ability of benchmarking such information across companies (Bray, 2002). The industry-based KPI-taxonomies of WICI (2010) are an attempt at creating such benchmarking possibilities. However, a recent contribution by Nielsen et al. (2017a) revokes this, arguing that comparability should be sought towards similar business models and not merely in accordance with the industry.

p.440

Sandberg (2002, p. 3) argues that this is because recent changes in the competitive landscape have given rise to a variety of new value creation models within industries where previously the “name of the industry served as shortcut for the prevailing business model’s approach to market structure”. Examples of this are the recent disruptions of the taxi industry by Uber, the hotel industry being disrupted by Airbnb, and Netflix disrupting the business model of Blockbuster. As Hamel (2000) states, competition now increasingly stands between competing business concepts. Therefore, context needs to be capable of providing enough information for users to understand exactly how it is a given company has chosen to compete in its industry.

Business reporting themes

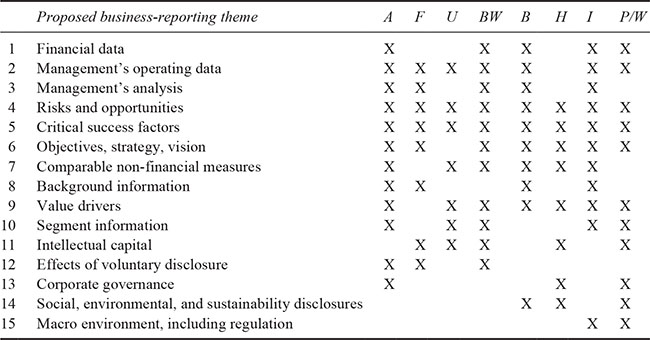

The previous section highlighted shifts in the conception of relevant stakeholders, but also that information relevant to management is also relevant to the investor community. This section establishes the types of information recommended by standard-setting bodies and other institutions since the late 1990s that companies disclose in order to meet demands for ‘full information’ from the investment community and other stakeholders. For the purpose of this discussion, eight different business reporting frameworks have been selected for review. The reports considered are: Improving Business Reporting: A Customer Focus – Meeting the Information Needs of Investors and Creditors, also referred to as the Jenkin’s Report (AICPA, 1994), coded A; Improving Business Reporting: Insights into Enhancing Voluntary Disclosures (FASB, 2001), coded F; Business and Financial Reporting: Challenges from the New Economy (Upton, 2001), coded U; Unseen Wealth (Blair and Wallman, 2001), coded BW; New Directions in Business: Performance Reporting, Communication and Assurance (Bray, 2002), coded B; Sustainable Development Reporting: Striking the Balance (Heemskerk et al., 2003), coded H; Management Commentary Exposure Draft (IASB, 2009), coded I; and The Corporate Reporting Framework (originally published in Eccles et al., 2001, now used by WICI and PwC), coded P/W.

An overview of the types of information recommended by these frameworks is provided in Table 27.1. A wide spectrum of information, ranging from the more traditional financial and operating data, to management’s analysis of data, to more forward-oriented information such as critical success factors, strategy, and IC are covered in these frameworks. Together, these types of information might be said to constitute the content of what a so-called flag-ship performance report should contain (Bray, 2010).

The model for business reporting proposed by Jenkins (AICPA, 1994, p. 44) initially identified ten components to be included in a corporate report and thereby also constitute the backbone of management commentary. Table 27.1 illustrates that there is broad agreement among the reports reviewed regarding the inclusion of elements such as management’s operating data, management’s analysis of financial and operating data, information on risks and opportunities, critical success factors, value drivers, objectives, strategy, and vision.

p.441

Table 27.1 Business reporting recommendation themes

A much-applied critique of the ‘usefulness’ of narrative reporting has been the question of objectivity and timeliness of management commentary (Dumay and Guthrie, 2017). This becomes especially problematic in relation to the macro environment and the competitive landscape, where the situation can change even between the writing and publishing of the narrative report. The investment community states in relation to this problem that the application of other information channels is a necessity for their decision making (Nielsen, 2005b; Bukh and Nielsen, 2010). Professional users apply a wide array of information sources and channels in addition to the annual report in order to enhance their contextual understanding (Holland, 2004). Such types of information may include competitors’ data, market research reports, trade magazines, and face-to-face management briefings.

Other areas emphasized by these eight reports include segment information such as the break-up of information by line of business and type of expenditure (FASB, 2001), and generally the use of key performance indicators along multiple dimensions (Bray, 2002). Likewise, the significance of intangibles for value creation, as argued by Lev (2001), invokes that additional data about IC, including human resources, customer relationships, and innovation, is recommended in a majority of the reports. This category of information depicts the processes and infrastructure put in place to achieve organizational objectives (Bray, 2002, p. 13) and is thus important for understanding business models (Dane-Nielsen and Nielsen, 2017).

IC has been a major discourse within business reporting since the late 1990s (Beattie and Smith, 2013), but this particular theme seems to recently have been encapsulated by the <IR> discourse as an input-capital (Nielsen et al., 2016). Early on in the debate, Bukh (2003) suggested the business model as a potential organizer of voluntary information such as that of IC, a message that Beattie and Smith (2013) later reinforced. The recent <IR> framework does, in fact, make use of the term business model as a central frame of reference; however, the IIRC’s understanding of business models seems to be distanced from the mainstream, implying a focus on value propositions and customer value creation and delivery (Nielsen and Roslender, 2015). In the next section, we examine how companies can apply the ideas of the business model as a platform for strategy and thereby also as a platform for structuring the narrative sections of business reporting.

p.442

Business models as platforms for structuring narratives

The previous section highlighted which types of voluntary information were considered relevant for users of business reporting. Users were primarily understood as the representatives of the investment community. Despite the distinct investor focus of the eight reports reviewed in the previous section it is, however, worth noting that three of the reports studied argue for the mobilization of multiple stakeholders as recipients of information (Eccles et al., 2001; Bray 2002; Heemskerk et al. 2003) and the importance of linking social and environmental measures to business objectives (Heemskerk et al. 2003). <IR> (IIRC, 2013a) takes an investor focus on business reporting, but argues for the importance of reporting about the effects of the corporation towards a broad stakeholder base. Hence it takes a perspective focused on reporting about stakeholders, rather than reporting for stakeholders.

Dumay et al. (2017) argue that there is a reporting resurgence in IC. However, this resurgence, they suggest, may be short lived if it only focuses on investors and managers, as it is no longer considered responsible for companies to prioritize profits before people and the environment. Therefore, there needs to be more research to understand how IC helps develop value beyond organizational boundaries, and this can be supported from a business model perspective. This is because business models naturally lend themselves to describing firms and firm boundaries by distinguishing between (i) internal value creation mechanisms of the firm, (ii) focal firm value creation that includes the immediate stakeholders such as suppliers and partners, and (iii) the broader societal effects of firm activities. Nielsen (2005a) provides the following definition of a business model:

A business model describes the coherence in the strategic choices which makes possible the handling of the processes and relations which create value on both the operational, tactical and strategic levels in the organization. The business model is therefore the platform which connects resources, processes and the supply of a service which results in the fact that the company is profitable in the long term.

According to Nielsen’s (2005a) definition, the business model bears closest resemblance to understanding the focal firm’s value creation that includes the immediate stakeholders. The business model is concerned with delivering the value proposition of the company, but it is not the value proposition alone that makes a business model. It is, in itself, supported by a number of parameters and mechanisms relating to how the value proposition of the company is implemented. Conceptualizing the business model is therefore concerned with identifying the platform that connects resources and processes to value delivery. Analysing the business model, on the other hand, is concerned with gaining an understanding of precisely which levers of control are apt to deliver the value proposition of the company, while communicating the business model is concerned with identifying the most important performance measures, both absolute and relative measures, and relating them to the overall value creation story.

p.443

In line with Baden-Fuller and Morgan’s (2010) terminology of business models as role models of ways to do business, and Lund and Nielsen’s (2014) examples of business models as narratives capable of visualizing a set of complex future business options, Beattie and Smith (2013, p. 253) state that the business model concept offers a powerful overarching concept within which to refocus the IC debate, because business model narratives hold promise for linking value creation and value delivery with the value realization (capture) trajectory of the financial reporting profession (Nielsen and Roslender, 2015). However, if firms only disclose key performance indicators without disclosing the business model that explains the interconnectedness of the indicators (Bukh, 2003) and why precisely this bundle of indicators is relevant for understanding the firms’ value creation (Nielsen et al., 2017a), then chances are external users of the information are going to have a hard time making sense, let alone make judgements.

According to Montemari and Chiucci (2017), there exists little current research-based insight into how such an analysis and interpretation might be conducted. However, Nielsen et al. (2017a) and Dane-Nielsen and Nielsen (2017) illustrate that it is possible to analyse IC from a business model perspective and from this perspective to identify performance measures based on the specific business model configuration employed by a given company (Taran et al., 2016).

Although <IR> (IIRC, 2013b) places the business model at the centre of its framework, the IIRC’s particular interpretation of business models leaves out some very central notions of contemporary understandings, including the critical notion of the value proposition (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010), and this is problematic if it is to connect to how companies work with business model design and business model innovation internally. For Nielsen and Roslender (2015), a business model provides a framework for visualizing the relationship that exists between the three components of a generic value creation focus: 1) value creation; 2) value delivery; and 3) value capture. This should then also be visualized in management commentary.

Figure 27.2 IIRC’s business model

p.444

Figure 27.3 A business model canvas of Skype (adapted from Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010)

The point of departure for some suggestions in relation to voluntary reporting and management commentary is to illustrate the flows of value creation by linking it to performance measures (Nielsen et al., 2009), thus in turn connecting performance measures with management commentary. Mouritsen and Larsen (2005) label this a process of “entangling” the indicators, arguing that individual pieces of information and measurements by themselves can be difficult to relate to any conception of value creation. The problem with trying to visualize the company’s business model is that it often ends up becoming a generic organization diagram illustrating the process of transforming inputs to outputs in a chain-like fashion like that depicted by the IIRC itself in Figure 27.2. As such, potential readers must be left wondering what is the core of the organization, because key differentiating aspects of the business model are drowned in attempts to illustrate the whole business. This is why the communicative aspects of focusing the information are so important (Nielsen and Madsen 2009).

Instead, the illustration of the business model should be focused on the connections between the different elements into which we traditionally divide the management review. This is illustrated in Figure 27.3, which shows the value drivers of Skype’s business model in a Business Model Canvas and the key connections between these. Skype applies a Freemium1 business model where approximately 90 per cent of the customers use a free service, while the remaining 10 per cent pay for a premium service. It is the critical mass provided by the free customer segment that creates the willingness of the premium customers to pay. The software platform that connects people globally is a crucial element of the business, and the key differentiator between Skype and traditional phone companies is that Skype does not carry the costs of land or GSM network installations. This is the company’s cost advantage.

Companies typically report excessive amounts of information about customer relations, employee competences, knowledge sharing, product innovation, market developments, and risks, but this information set may be useless if the company at the same time fails to illustrate how these various elements of value creation interrelate; not to mention which changes in the company and its environment are most crucial to watch. It is crucial for the readers’ understanding of the business model that the company presents a coherent picture of the company’s value creation, for example by providing an insight into the interrelations that induce value creation in the company. Bearing in mind that providing unlimited datasets to users too may be problematic as it will lead to an information overload. In a study of IC reporting practices, Nielsen and Madsen (2009) discuss how such business reporting practices have moved from generic reporting practices stressing the disclosure of as much information to stakeholders as possible, towards a new discourse, which emphasizes reporting what is seen from the perspective of management, namely the ‘right’ information, and only that.

p.445

A company’s business model should be supported by non-financial performance measures. It is one thing to state that the business model of a company relies heavily on mobilizing customer feedback in the innovation process, and quite another to explain how this will be achieved. It is even more demanding for the company to prove this effort by indicating: 1) how many resources the company devotes to it; 2) how active the company is in trying to achieve it, and whether it stays as focused as initially announced; and 3) whether the effort has had any effect, for example, on customer satisfaction, innovation output, and so on. According to Bray (2010, p. 6):

[r]elevant KPIs measure progress towards the desired strategic outcomes and the performance of the business model. They comprise a balance of financial and non-financial measures across the whole business model. Accordingly, business reporting integrates strategic, financial and non-financial information, is future-performance focused, delivered in real time, and is fit for purpose.

One of the keys to making management commentary matter to the investment community is therefore to emphasize the interconnectedness between parts of the narrative sections according to the logic of the business model. The adoption of <IR> has not yet stimulated new innovations in disclosures and disclosure mechanisms, which might be due to the fact that the disclosure guidance seems to be poor (Nielsen, 2006; Dumay et al., 2017; Nielsen et al., 2017b) and that the IIRC seems dismissive of the current rapid transformation in technologies and forces of mass communication (Dumay and Guthrie, 2017).

A final word of caution relates to how to compare business model information. The investment community loves to compare and to benchmark. However, they will need to change their mindset, because in today’s business environment, the industry is not a proxy for a certain type of business model (Lev and Gu, 2016). If firms within the same industry operate on the basis of different business models, then different sets of competencies and knowledge resources will be key parts of value creation. Instead, in order to create meaningful comparisons, these must be conducted between identical business models (Nielsen et al., 2017a). Montemari and Chiucci (2017) point out that the advantage of the business model is that it clarifies which IC elements are of the greatest importance and also what role they play in the company’s value creation process. Thereby, the business model may prove itself an organizing element for companies wishing to compare and benchmark their IC information.

Conclusions

A business model description goes beyond an identification of the company’s immediate cash flows to describe the company’s value creating activities, the way it delivers and connects to customers, and the way it captures value from those transactions. In capital market language, one would say it is a statement on how the company will survive beyond the end of the budget period.

p.446

This chapter discussed the usefulness of IC in relation to the investment community and other stakeholders using voluntary corporate information. While many early contributions in the fields of management commentary and business reporting aspired towards creating higher volumes of information from companies, some of the later contributions are more concerned with focusing on the information set. Some information is better than none, but we all know that there is a limit to the amount of information users can screen and apply, even for expert users like institutional investors and analysts (Plumlee, 2003). Passing a certain threshold will move the general understanding of the company away from transparency rather than towards it (Nielsen and Madsen, 2009). It will therefore have to be contended whether a “flag-ship business report”, as Bray (2010) describes, should entail real-time insight on financial and non-financial performance measures to the capital market that potentially could feed into analyst models.

A solution that would make IC reporting matter (more) to the investment community is one that emphasizes the interconnectedness between parts of the narrative sections according to the logic of contemporary business model understandings. These are built on value propositions (Osterwalder and Pigneur, 2010) and not value chains as applied in <IR> (IIRC, 2013b).

This chapter identified a series of inconsistencies due to a mismatch between business reporting orientation and the general stakeholder orientation in the business community. While Eccles and Krzus (2010) illustrate the possibility of integrating financial reporting with social and environmental reporting, Bray (2010) suggests that the social and environmental reporting movement is moving towards the capital markets and furthermore that early adopters potentially could build impetus for later regulation. However, such a movement will give rise to conflicts of interest as such professional stakeholders will be more apt to pursue a normative perspective on disclosure streams. Hence, this chapter concludes that propositions of aligning management commentary with business models may lead to challenges for both companies and external stakeholders, and that regulation should be concerned with creating guidance on how to structure management commentary and strengthen such narrative statements through relevant performance measures.

We have argued that management commentary sections need to be aligned with the logic of the business model applied by the specific company, thereby describing the specific structures and strategies of value creation. This would enable the identification of performance measures that could enhance the credibility of the reporting. One of the keys to making IC matter to the investment community is therefore to emphasize the interconnectedness between parts of the narrative sections according to the logic of the business model; but a logic that, according to Tweedie et al. (forthcoming), is different from the misunderstood conception applied by the IIRC (2013b). From a regulation perspective, this chapter therefore concludes that guidance should be concerned with helping companies structure and strengthen their narrative statements by helping them in defining possible relevant performance measures and explaining these.

Note

1 The term Freemium was coined by Anderson (2009).

References

Adrem, A. (1999), Essays on Disclosure Practices in Sweden: Causes and Effects, Doctoral dissertation, Institute of Economic Research, University of Lund, Sweden.

p.447

AICPA (1994), Improving Business Reporting: A Customer Focus: Meeting the Information Needs of Investors and Creditors; and Comprehensive Report of the Special Committee on Financial Reporting, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, New York.

Anderson, C. (2009), Free: The Future of a Radical Price, Random House, London.

Arnold, J. and Moizer, P. (1984), “A survey of the methods used by UK investment analysts to appraise investments in ordinary shares”, Accounting and Business Research, Vol. 14, No. 55, pp. 195–207.

Baden-Fuller, C. and Morgan, M. (2010), “Business models as models”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 43, Nos 2–3, pp. 156–171.

Bartlett, S. A. and Chandler, R. A. (1997), “The corporate report and the private shareholder: Lee and Tweedie twenty years on”, British Accounting Review, Vol. 29, pp. 245–261.

Beattie, V. and Pratt, K. (2002), Voluntary Annual Report Disclosures: What Users Want, Institute of Chartered Accountants, Scotland.

Beattie, V. and Smith, S. J. (2013), “Value creation and business models: Refocusing the intellectual capital debate”, British Accounting Review, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 243–254.

Blair, M. and Wallman, S. (2001), Unseen Wealth, Brookings Institution, Washington, DC.

Botosan, C. A. (1997), “Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 323–349.

Bray, M. (2002), New Directions in Business: Performance Reporting, Communication and Assurance, The Institute of Chartered Accountants in Australia.

Bray, M. (2010), The Journey to Better Business Reporting: Moving Beyond Financial Reporting to Improve Investment Decision-making, KPMG, Sydney, Australia.

Bukh, P. N. (2003), “The relevance of intellectual capital disclosure: A paradox?” Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 49–56.

Bukh, P. N. and Nielsen, C. (2010), “Understanding the health care business model: The financial analyst’s point of view”, Journal of Health Care Finance, Vol. 37, No. 2, pp. 8–25.

Bukh, P. N., Nielsen, C., Gormsen, P., and Mouritsen, J. (2005), “Disclosure of information on intellectual capital in Danish IPO prospectuses”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 18, No. 6, pp. 713–732.

Christensen, J. A. and Demski, J. S. (2003), Accounting Theory: An Information Content Perspective, McGraw-Hill, Boston, MA.

Cooke, T. E. (1989), “Voluntary corporate disclosure by Swedish companies”, Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting, Vol. 1, pp. 171–195.

Dane-Nielsen, H. and Nielsen, C. (2017), “Value creation in business models is based on intellectual capital: And only intellectual capital!” in Guthrie, J., Dumay, J., Ricceri, F., and Nielsen, C. (Eds), The Routledge Companion to Intellectual Capital, Routledge, London, pp. 418–434.

De Villiers, C., Rinaldi, L., and Unerman, J. (2014), “Integrated reporting: Insights, gaps and an agenda for future research”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 27, No. 7, pp. 1042–1067.

DiPiazza, S. A. Jr. and Eccles, R. G. (2002), Building Public Trust: The Future of Corporate Reporting, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York.

Dumay J. (2016), “A critical reflection on the future of intellectual capital: From reporting to disclosure”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 168–184.

Dumay, J. and Guthrie, J. (2017), “Involuntary disclosure of intellectual capital: Is it relevant?” Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 29–44.

Dumay, J., Bernardi, C., Guthrie, J., and Demartini, P. (2016), “Integrated reporting: A structured literature review”, Accounting Forum, Vol. 40, No. 3, pp. 166–185.

Dumay, J., Guthrie, J., and Rooney, J. (2017), “The critical path of intellectual capital”, in Guthrie, J., Dumay, J., Ricceri, F., and Nielsen, C. (Eds), The Routledge Companion to Intellectual Capital, Routledge, London, pp. 21–39.

Eccles, R. G. and Krzus, M. (2010), One Report: Integrated Reporting for a Sustainable Strategy, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Eccles, R. G., Herz, R. H., Keegan, E. M., and Phillips, D. M. (2001), The Value Reporting Revolution: Moving Beyond the Earnings Game, John Wiley and Sons, Inc., New York.

Eustace, C. (2001), The Intangible Economy: Impact and Policy Issues, Report of the High Level Expert Group on the Intangible Economy, EU Commission, Brussels.

FASB (2001), Improving Business Reporting: Insights into Enhancing Voluntary Disclosures, Steering Committee Business, Reporting Research Project, Financial Accounting Standard Board, London.

p.448

Fisher, R., Oyelere, P., and Laswad, F. (2004), “Corporate reporting on the internet: Audit issues and content analysis of practices”, Managerial Auditing Journal, Vol. 19, No. 3, pp. 412–439.

GRI (2002), Sustainability Reporting Guidelines, Global Reporting Initiative, Boston, MA.

Gu, F. and Li, J. Q. (2007), “The credibility of voluntary disclosure and insider stock transactions”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 45, No. 4, pp. 771–810.

Hamel, G. (2000), Leading the Revolution, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, MA.

Heemskerk, B., Pistorio, P., and Scicluna, M. (2003), Sustainable Development Reporting: Striking the Balance, World Business Counsel for Sustainable Development (WBCSD), Geneva.

Holland, J. (2004), Corporate Intangibles, Value, Relevance and Disclosure Content, Institute of Chartered Accountants of Scotland, Edinburgh, UK.

Holland, J. B. and Johanson, U. (2003), “Value relevant information on corporate intangibles: Creation, use, and barriers in capital markets – Between a rock and a hard place”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 465–486.

Holman, R. (2002), “The annual report of the future”, CrossCurrents, No. 3, pp. 4–9.

IASB (2009), Management Commentary, Exposure Draft ED/2009/6, IASC Foundation Publications Department, London.

IIRC (2013a). The International IR Framework, International Integrated Reporting Council. Available at: www.iirc.org.

IIRC (2013b), Business Model: Background Paper for Integrated Reporting, International Integrated Reporting Council, London. Available at: www.theiirc.org.

Lang, M. H. and Lundholm, R. J. (1993), “Cross-sectional determinants of analyst ratings of corporate disclosures”, Journal of Accounting Research, Vol. 31, No. 2, pp. 246–271.

Lang, M. H. and Lundholm, R. J. (1996), “Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behaviour”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 71, No. 4, pp. 467–492.

Lee, T. A. and Tweedie, D. P. (1977), The Private Shareholder and the Corporate Report, Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, London.

Lee, T. A. and Tweedie, D. P. (1981), The Institutional Investor and Financial Information, Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales, London.

Lev, B. (2001), Intangibles: Measurement, Management and Reporting, Brookings Institution Press, Washington, DC.

Lev, B. and Gu, F. (2016), The End of Accounting and the Path Forward for Investors and Managers, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Lund, M. and Nielsen, C. (2014), “The evolution of network-based business models illustrated through the case study of an entrepreneurship project”, Journal of Business Models, Vol. 2, No. 1, pp. 105–121.

March, J. G. and Olsen, J. P. (1989), Rediscovering Institutions: The Organizational Basis of Politics, The Free Press, New York.

McEwen, R. A. and Hunton, J. E. (1999), “Is analyst forecast accuracy associated with accounting information use?” Accounting Horizons, Vol. 13, No. 1, pp. 1–16.

Mintzberg, H. and Van der Heyden, L. (1999), “Organigraphs: Drawing how companies really work”, Harvard Business Review, September-October, pp. 87–94.

Montemari, M. and Chiucci, M. S. (2017), “Enabling intellectual capital measurement through business model mapping: The Nexus case”, in Guthrie, J., Dumay, J., Ricceri, F., and Nielsen, C. (Eds), The Routledge Companion to Intellectual Capital, Routledge, London, pp. 266–283.

Mouritsen, J. and Larsen, H. T. (2005), “The 2nd wave of knowledge management: The management control of knowledge resources through intellectual capital information”, Management Accounting Research, Vol. 16, No. 4, pp. 371–394.

Nielsen, C. (2005a), “Comments on the IASB discussion paper concerning Management Commentary”, Available at: www.iasb.org/current/comment_letters.asp.

Nielsen, C. (2005b), Essays on Business Reporting: Production and Consumption of Strategic Information in the Market for Information PhD Dissertation, Copenhagen Business School.

Nielsen, C. (2006), “Comments on the IASB discussion paper concerning Management Commentary”, Available at: www.ifrs.org/Current-Projects/IASB-Projects/Management-Commentary/DP05/Comment-Letters/Documents/16_230_CL2.pdf (accessed 27 September 2016).

Nielsen, C. (2008), “A content analysis of analyst research: Health care through the eyes of analysts”, Journal of Health Care Finance, Vol. 34, No. 3, pp. 66–90.

Nielsen, C. and Madsen, M. T. (2009), “Discourses of transparency in the intellectual capital reporting debate: Moving from generic reporting models to management defined information”, Critical Perspectives on Accounting, Vol. 20, No. 7, pp. 847–854.

p.449

Nielsen, C. and Roslender, R. (2015), “Enhancing financial reporting: The contribution of business models”, British Accounting Review, Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 262–274.

Nielsen, C., Bukh, P. N., Mouritsen, J., Johansen, M. R., and Gormsen, P. (2006), “Intellectual capital statements on their way to the Stock Exchange: Analyzing new reporting systems”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 7, No. 2, pp. 221–240.

Nielsen, C., Lund, M., and Thomsen, P. (2017a), “Killing the balanced scorecard to improve internal disclosure”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 45–62.

Nielsen, C., Roslender, R., and Bukh, P. N (2009), “Intellectual capital reporting: Can a strategy perspective solve accounting problems?” in Lytras, M. D. and Ordóñez de Pablos, P. (Eds), Knowledge Ecology in Global Business, IGI Global, Hershey, PA, pp. 174–191.

Nielsen, C., Roslender, R., and Schaper, S. (2016), “Continuities in the use of the intellectual capital statement approach: Elements of an institutional theory analysis”, Accounting Forum, Vol. 40, No. 1, pp. 16–28.

Nielsen, C., Roslender, R., and Schaper, S. (2017b), “Explaining the demise of the intellectual capital statement in Denmark”, Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, Vol. 30, No. 1, pp. 38–64.

Osterwalder, A. and Pigneur, Y. (2010), Business Model Generation: A Handbook for Visionaries, Game Changers, and Challengers”, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, NJ.

Pike, R. H., Meerjanssen, J., and Chadwick, L. (1993), “The appraisal of ordinary shares by investment analysts in the UK and Germany”, Accounting and Business Research, Vol. 23, No. 92, pp. 489–499.

Plumlee, M. A. (2003), “The effect of information complexity on analysts’ use of that information”, The Accounting Review, Vol. 78, No. 1, pp. 275–296.

PWC (2007), “Corporate Reporting: Is It What Investment Professionals Expect? Pricewaterhouse Coopers International Limited, London.

Roslender, R. and Nielsen, C. (2017), “Lessons for progressing narrative reporting: Learning from the experience of disseminating the Danish Intellectual Capital Statement approach”, unpublished working paper.

Sandberg, K. D. (2002), “Is it time to trade in your business model?”, Harvard Management Update, January, pp. 3–5.

Söderbaum, P. (2002), “Business corporations, markets and the globalisation of environmental problems”, in Havila, V., Forsgren, M., and Håkansson, H. (Eds), Critical Perspectives on Internationalisation, Pergamon, Amsterdam, pp. 179–200.

Taran, Y., Nielsen, C., Thomsen, P., Montemari, M., and Paolone, F. (2016), “Business model configurations: A five-V framework to map out potential innovation routes”, European Journal of Innovation Management, Vol. 19, No. 4, pp. 492–527.

Tweedie, D., Nielsen, C., and Martinov-Bennie, N. (forthcoming), “Evolution or abandonment? Contextualising the business model in integrated reporting”, Australian Accounting Review.

Upton, W. S. (2001), Business and Financial Reporting: Challenges from the New Economy, Special Report, Financial Accounting Standard Board.

Vanstraelen, A., Zarzeski, M. T., and Robb, S. W. G. (2003), “Corporate nonfinancial disclosure practices and financial analyst forecast ability across three European countries”, Journal of International Financial Management and Accounting, Vol. 14, No. 3, pp. 249–278.

WICI (2010), Concept Paper on WICI KPI in Business Reporting, World Intellectual Capital/Assets Initiative. Available at: www.wici.org.

WICI (2016), WICI Intangible Reporting Framework, Version 1, September 2016, World Intellectual Capital/Assets Initiative. Available at www.wici.org.