Table 29.1 Descriptive statistics

p.463

DOES INTELLECTUAL CAPITAL MATTER FOR ORGANIZATIONAL PERFORMANCE IN EMERGING MARKETS?

Evidence from Chinese and Russian contexts

Aino Kianto, Tatiana Garanina, and Tatiana Andreeva

Introduction

In understanding the foundations of organizational performance, the knowledge-based approach has emerged as a key perspective in which a firm’s intellectual capital (IC) is seen as a major driver of organizational success and a source of competitive advantage (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Sveiby, 1997; Nahapiet and Ghoshal, 1998; Petty and Guthrie, 2000; Ricceri, 2008; Dumay and Guthrie, 2012). There is widespread agreement that IC significantly impacts organizational performance, and extensive empirical research in developed countries confirms this relationship (e.g. Edvinsson, 1997; Johnson and Soenen, 2003; Tseng and Goo, 2005; Wu and Tsai, 2005; Puntillo, 2009).

But is this the same for emerging markets? Does IC matter in this context? In many emerging countries, the economy depends heavily on natural or other tangible resources – indeed, resource extraction in emerging economies more than doubled between 1985 and 2005 (Dittrich et al., 2011). The quality of available human capital in these labour markets may also differ, and executives frequently complain about the gap between the needs of industry and the skills and knowledge acquired in domestic universities.1 Additionally, emerging countries suffer from a ‘brain drain’, as the most skilled and experienced candidates leave for developed countries, whose search for talent extends worldwide (PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2014).

It seems likely, then, that the relevance of IC and its contribution to the performance of firms in emerging markets may differ from the findings in the mainstream IC literature. IC research in general thus far has progressed through three main stages (Guthrie et al., 2012; Dumay and Garanina, 2013; Dumay, 2013):

1 creation of awareness of the phenomenon and importance of IC;

2 building and testing normative IC frameworks; and

3 critical and performative approach to IC and its management.

p.464

Along with its call for idiosyncratic and practice-based understandings of IC, the third stage, if somewhat implicitly, invites a more contextual and localized approach to IC. However, such an approach has been little applied in the extant IC research. In line with recent calls for the deeper contextualization of theories developed in the West (Michailova, 2011; May and Stewart, 2013), we suggest that a better understanding of the role of IC in emerging markets can enrich and advance IC theory, as well as helping managers of both multinational companies and local businesses to achieve greater efficiencies by understanding cross-cultural differences.

The research question examined in this chapter is: how does IC impact the performance of companies in China and Russia? These major emerging economies are of particular interest to IC research for several reasons. First, both have joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) relatively recently (China in 2002 and Russia in 2012). As they become more integrated into the global economy, the competitive pressures on Chinese and Russian companies have intensified substantially, forcing them to develop and exploit IC to survive and succeed (Kianto et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). In this environment, IC management can be an important means of enhancing financial efficiency, and as both countries have also emphasized innovation in their plans for national development, IC management is likely to be of particular importance (Kianto et al., 2013).

It has been argued that there are fundamental differences between Western and Eastern countries in terms of knowledge and IC management practices (Jansson et al., 2007; Zhao, 2008; Kianto et al., 2013; May and Stewart, 2013). As China is a leading representative of Eastern management philosophy and Russia lies somewhere between Western and Eastern approaches, a comparison of the two systems should be especially interesting, both for further research and for its application to business.

Managing IC in China and Russia: putting the story in context

The dominant approach to IC, utilized by most researchers in the field, distinguishes it into three main elements: human, relational, and structural capital (Edvinsson and Malone, 1997; Stewart, 1997; Sveiby, 1997; Bontis, 1998; Molodchik et al., 2014). The following sections consider the peculiarities of the context in the two focal countries (China and Russia) that may potentially impact the quality and availability of intellectual resources, as well as how organizations manage those resources. These are presented by the three main elements of IC.

The Chinese Government has recently begun to pay more attention to education as the most direct means of improving the value of human capital. For example, in 1998, China’s Ministry of Education announced its “211 Project”, selecting some 60 universities for a national programme to improve teaching systems and enhance human capital (Zhao, 2008). In line with such government policies to intensify the development of human capital, Chinese corporations now invest increasingly in internal training systems to enhance the generation of new ideas and knowledge sharing among employees (Zhao, 2008). Now, leading companies abroad employ many Chinese people who are “elite in science and technology” (Chen et al., 2004, p. 198).

At the same time, there is some evidence of a lack of talented employees, particularly among managers and professionals (Farrell and Grant, 2005; Tung, 2007; Zhu et al., 2008). Because industrial enterprises in China have paid insufficient attention to developing IC – and especially human capital – for a long time (Liu and White, 2001), most human capital is concentrated within research institutes, universities, and subsidiaries of foreign companies (Chen et al., 2015), and there is considerable scope for improvement in this regard.

p.465

Chinese culture has a positive influence on knowledge sharing, enhancing a company’s human capital through Guanxi-principles of collectivism and Confucian dynamism that influence the specifics of knowledge management in China (Yeh et al., 2006; Chang and Lee, 2007; Lin and Dalkir, 2010). Guanxi is a very important element in trust-based relations and is considered to increase the efficiency of knowledge sharing (Hutchings and Michailova, 2006; Hutchings and Weir, 2006). As a shared value, collectivism may help to increase the intensity of knowledge exchange between employees, so enhancing human capital. With its focus on harmony, Confucian dynamism also positively supports knowledge sharing (Huang et al., 2008). For example, Chinese employees strive for more harmony and compromise in group work, which leads to a higher level of knowledge sharing than in groups consisting of US nationals (Jiacheng et al., 2010).

In the context of human capital, Russia has traditionally been characterized by a strong legacy of scientific and technological excellence, and many of its companies have their roots in research establishments, reflecting a focus on processes of renewal and development (Tovstiga and Tulugurova, 2009). Employees in these kinds of Russian enterprises show a high level of competence, reflecting scientific and technical expertise, and professionalism. At the same time, it is important to mention a Grant Thornton survey of 34 countries indicating that the main problem faced by Russian companies is a lack of qualified personnel (Domcheva, 2014). Employee outflow from Russia is very high, and the country is currently experiencing the largest brain drain in 20 years. According to Russia’s state statistical agency, 350,000 people emigrated from Russia in 2015 – ten times more than five years ago (Bershidsky, 2016).

The intensity and efficiency of a company’s human capital depend on knowledge management practices. The barriers to effective implementation of knowledge management systems created by the complexity of Russian business culture are analysed in Michailova and Husted (2003), Michailova and Hutchings (2006), and May and Stewart (2013). First, although Russian culture is usually said to be characterized by collectivism, it is very common for Russian people to split into their own small group versus “the others” (Michailova and Hutchings, 2006), precluding efficient knowledge sharing outside this group (Michailova and Husted, 2003). Michailova and Hutchings (2006) go on to say that Russian employees are very sensitive to distance setting, and they identify three levels of division: the company as a whole, all employees, and colleagues. This leads to a lack of knowledge sharing intensity between groups and hinders implementation of knowledge sharing systems, which may in turn obstruct enhancement of human capital.

Second, it is a norm of Russian culture that knowledge is correlated with personal status and power. As a consequence, employees do not tend to share knowledge unnecessarily or without gaining some material benefit (Michailova and Husted, 2003; Michailova and Hutchings, 2006). This is a legacy of the Soviet era, when all information flows were strictly controlled and people were afraid to share information (May and Stewart, 2013). This characteristic again blocks knowledge sharing, making enhancement of a company’s human capital less efficient.

In summary, then, China and Russia differ in their capacity to develop human capital. In combination with the particularities of Chinese culture, government support to improve the national educational system and investment by Chinese companies in internal training systems can be expected to create a friendly environment for the enhancement of human capital, positively influencing company financial performance. At the same, however, it should be noted that this strong focus on human capital has emerged only relatively recently (Liu and White, 2001), and that much of that human capital is concentrated in research institutes, universities, and subsidiaries of foreign companies (Chen et al., 2015). In contrast, the Russian situation is characterized by several factors that weaken the development of human capital, including a poor knowledge sharing environment, a poor economic situation, and high levels of brain drain.

p.466

In terms of China, the second element of IC, relational capital, is impacted by peculiarities of local relational systems. Chinese business networks are characterized by family business systems that have been widespread in Southeast Asia for a long time (Jansson et al., 2007) and are considered the organizing principle of economic activity (Hamilton, 1996). Membership is a matter not just of gaining admission to the network but of becoming a trusted member in a networked market (Ramström, 2005). Personal relations in China are very strong, and these form the base for firm-specific relations. As relations are highly personified, and the principle of collectivism also predominates, these networks have a deterministic rather than a supporting role in business relationships (Jansson et al., 2007). Chinese business networks are socially strong, last for many years and “represent a continuity of collective common interests (families, communities, and sets of friends and relatives)” (Jansson et al. 2007, p. 960). In this environment, it is not uncommon to contact someone you know to resume business relations even after a long break.

In general, formal and written control and regulations are much less important in Chinese business than informal relations. This preference for personal relations over formal contracts is a matter of flexibility (Michailova and Worm, 2003). In Chinese business culture, it is much worse to be blacklisted than to be sued in court, as all the members of that business network will terminate relations (Jansson et al., 2007).

In the context of relational capital, the characteristics of Russian culture are reflected in how personal relations often precede or even become a prerequisite for business relationships (Salmi, 1996; Michailova and Worm, 2003). Networking is now a key element of doing business in Russia, and Russian companies appear to be skilled in this regard (Puffer and McCarthy, 2011). For that reason, one might expect relational capital to be of particular importance for Russian companies. Hutchings and Michailova (2004) confirmed that what is sometimes considered a negative aspect of Russian culture in fact creates new opportunities for knowledge sharing and enrichment of relational capital. The importance of personal relations in business can be explained by the weak legitimacy of formal institutions (Puffer and McCarthy, 2011; McCarthy et al., 2012).

Russian business networks are based more on autonomous individuals and voluntary individual actions (Jansson and Ramström, 2005). Additionally, the unstable economic situation and generally volatile environment means that Russian networks are oriented to the short term and are characterized by an absence of trust and reputation (Gurkov, 1996). Russian businessmen tend not to adapt their relations to deal with new environmental conditions, but rather terminate them and seek new partners (Hallén and Johanson, 2004). According to Huber and Wörgötter (1998), the closed and hierarchical survivalist networks that now predominate in Russia emerged from ‘grey’ markets and are based on ties created during the socialist era. However, with entry to the WTO and integration into the global environment, the role of these networks should diminish, as they stand in sharp contrast to the international business networks found in most Western countries.

While China and Russia differ in some respects, such as who is included in the relationship network and how exactly these relationships are built and maintained (Wong and Tam, 2000; Jansson et al., 2007), the present analysis confirms that relationships play a very important role in business in both countries. It seems reasonable to assume, then, that organizations in such contexts would typically exhibit strongly developed relational capital.

In the Chinese context, the third IC element, structural capital, is impacted by the tendency of Chinese companies to put a strong focus on competitiveness and performance indicators as they are going global. To achieve their ambitious goals, Chinese companies must improve internal business processes that are also balanced against social issues of high importance in society (Jansson et al., 2007). Chinese companies tend to be serious about the quality of internal business processes. For many companies, the implementation and certification of quality, environmental, and occupational health and safety management systems have been prioritized to increase market competitiveness (Zeng et al., 2007).

p.467

According to some observers, it is not always clear how Chinese companies work, as they seem to do little planning or budgeting (Ramström, 2005). This can be explained in terms of the flexibility of Chinese firms in volatile situations (Backman, 2001), which is closely linked to internal innovation. Chinese corporations are characterized by relatively high levels of R&D expenditure and patents. From their inception in 1985, patent applications have grown rapidly (Sun, 2000; Frietsch and Wang, 2007), securing the rights to new ideas developed in-house. There are two forms of innovation specific to Chinese companies: new products developed in China and introduced to the market, and products that quickly imitate foreign products (Li and Atuahene-Gima, 2001). The latter strategy also involves significant changes to existing products that improve consumer benefits and choice. According to Wang (2004), China has made great efforts to revise and upgrade its intellectual property-related legislation to meet the requirements of WTO membership. Nevertheless, there remains scope to improve the implementation and enforcement of intellectual property protection in terms of its efficiency (Wang, 2004).

In the context of structural capital, Russian companies face many environmental barriers (Andreeva and Garanina, 2016), one of which is that the level of protection of property rights is very low. Because the registration process is very time consuming, Russian organizations tend not to register intellectual property rights (Molodchik and Nursubina, 2012). Additionally, Russian companies often lack management competences and tend to rely too heavily on informal management mechanisms (Puffer and McCarthy, 2011), all of which lead to deficiencies in internal management processes (e.g. Gurkov et al., 2012), especially those for managing and retaining knowledge within an organization (Andreeva and Ikhilchik, 2011).

For Russian companies, it is usual to plan the development of internal processes. The autocratic leadership approach to company management means that the typical Russian manager thinks in terms of how to gain control over internal business processes and to maintain power over business operations within existing networks (Holt et al., 1994). Many researchers and businessmen have concluded that some of Russia’s economic problems relate to management inefficiency (Elenkov, 2002).

In summary, for both countries, entry to the WTO and the challenges presented by the economic environment have created the need for business process efficiency. At the same time, it can be said that the internal business processes of Chinese companies are much more flexible, increasing their potential competitiveness (Backman, 2001). Although Russian managers are used for planning, managerial efficiency in the country remains quite low (Elenkov, 2002), and certain bureaucratic difficulties (such as registration of intellectual property rights) weaken the development of structural capital, indicating that structural capital is better developed in Chinese companies.

Do IC elements matter for organizational performance in emerging markets?

The above discussion shows how characteristics of the Chinese and Russian contexts influence the quality and availability of IC to organizations, and how it is managed. However, more advanced development of a given element of IC need not have any significant effect on organizational performance. For example, on the basis of the above discussion, one might hypothesize that relational capital strongly influences business performance in China and Russia. However, this may not hold if the level is generally high in all of the companies; according to the logic of the resource-based view, in such a situation relational capital is no longer a unique and rare resource, meaning that it will not generate advantage over competitors (Dierickx and Cool, 1989; Barney, 1991). In such a circumstance, high relational capital would be needed just to enter the game (that is, doing business), but it would make little difference in terms of playing the game better than others.

p.468

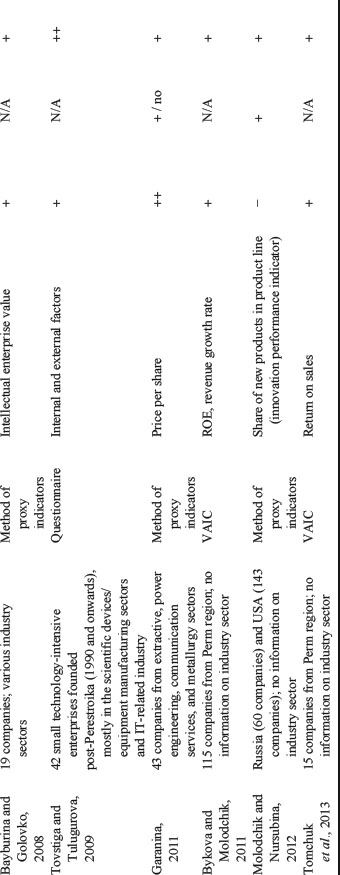

We have analysed the existing studies devoted to the relationship between IC elements and different performance indicators in Chinese and Russian companies. The Appendix presents an overview of empirical studies of the impact of IC on firm performance in China and Russia. It should be noted that these studies do not present a homogenous group of studies, but differ in several important respects. The studies have utilized various conceptualizations of the consistency of IC, different methods to measure IC, as well as various operationalizations for company performance, and different kinds of study samples. Of 16 papers, 9 only address human and structural capital as elements of IC, and leave relational capital unexamined. The methods applied for evaluating IC can be categorized in three types: questionnaires (Chen et al., 2004; Tovstiga and Tulugurova, 2009; Wang et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2015; Andreeva and Garanina, 2016), proxy indicators (Bayburina and Golovko, 2008; Garanina, 2011; Molodchik and Nursubina, 2012), and secondary data analysed with the Value Added Intangible Coefficient (VAIC) method by Pulic (2000) (Chan, 2009; Bykova and Molodchik, 2011; Chu et al., 2011; Tomchuk et al., 2013; Xiao, 2013; Lu et al., 2014). It should be noted that one of the disadvantages of the VAIC method is that it only addresses two elements of IC (human and structural capitals), and relational capital is out of its scope, meaning that all studies applying this method also adhere to the reduced conceptualization of IC. In terms of evaluation of organizational performance, some authors (e.g. Chan, 2009; Bykova and Molodchik, 2011; Tomchuk et al., 2013; Xiao, 2013; Lu et al., 2014) have focused on financial data that represent accounting (ROA, ROE, or ROS) and market performance indicators (market capitalization or Tobin’s Q), while others have concentrated not on financial but rather operational performance by analysing the innovative effectiveness of companies (Molodchik and Nursubina, 2012; Wang and Chen, 2013; Chen et al., 2015).

It was possible to identify eight previous studies that have empirically examined the impact of IC on company performance in the Chinese market. Chan (2009) examined 33 public companies traded on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange and found that structural capital positively impacted their financial performance, measured by market valuation, ROE, and ATO. Surprisingly, this study found that human capital had a negative effect on the performance metrics. With the help of the same evaluation approach to measure IC elements – VAIC – Chu et al. (2011) got almost the same results. These authors found that structural capital has a positive impact on financial performance while the results for human capital are mixed as it had either a positive or negative relationship with financial performance, depending on the indicators analysed. In their research, Lu et al. (2014) collected data from 34 Chinese life insurance companies. These authors came to the conclusion that both structural and human capitals had a positive relationship with the performance metrics measured with the help of the DEA method, with human capital prevailing. Xiao (2013) analysed 198 listed companies in China. With the help of the VAIC method, the author defined that both human and structural capitals are positively related to general growth indicators of total assets, net profit, revenue, and owners’ equity, with structural capital having a higher positive impact on financial performance. In the paper by Chen et al. (2004), the authors analyse the relationship between the performance index indicator and IC elements based on the data of 31 innovative companies in China. They came to the conclusion that human, structural, and relational capitals are positively related to financial performance.

p.469

There are also some papers where the authors analysed the impact of IC elements not only on financial performance (as for example in Chen et al., 2015), but also on innovative performance and innovative capabilities (Wang and Chen, 2013; Wang et al., 2014). The main differences in these papers are reflected in the power of the relationship between IC elements and performance indicators – some authors defined that the highest influence has the structural element (Chen et al., 2004; Wang and Chen, 2013) while the others came to the conclusion that relational capital is mostly related to financial and innovative indicators (Chen et al., 2015).

Seven empirical studies addressing the impact of IC on firm performance in Russia were identified. As in the case of studies examining Chinese firms, several authors have applied the VAIC methodology to the Russian context. Bykova and Molodchik (2011) analysed 115 companies from the Perm region and Tomchuk et al. (2013) considered 15 companies from the same region and found a positive relationship between human and structural capital and such financial performance indicators as ROE and ROS.

Tovstiga and Tulugurova (2007, 2009) used questionnaires to define the impact of IC elements on external (socio-political, technological, and economic) and internal performance indicators. Based on a sample of 42 small technology-intensive enterprises, the authors came to the conclusion that structural and human capital are positively related to companies’ performance indicators. Almost the same result was obtained by Andreeva and Garanina (2016) who surveyed 240 top managers of Russian manufacturing companies. They found that structural capital had a stronger influence on performance than human capital, while relational capital did not have a significant impact.

Several authors have used the method of proxy to analyse the IC elements on the Russian market with the help of open sources of information. The results of these studies have been very mixed. For example, Bayburina and Golovko (2008) chose 19 companies from various industry sectors and came to the conclusion that human and structural capital positively influence intellectual enterprise value. Garanina (2011) found a positive relationship between all three elements of IC and a price per share of 43 Russian companies from the extractive industry, power engineering, and communication services. Even though some industry differences were found, the general conclusion is that human capital has the strongest impact on the dependent variable. At the same time, Molodchik and Nursubina (2012) found a negative influence of human capital on a share of new products in the product line while relational and structural capital are positively related to this innovation performance indicator of 60 Russian companies.

As we can see, different studies have reported disparate results concerning the IC-performance relationship, from negative (e.g. Chan, 2009), through non-significant (Wang and Chen, 2013), to positive (e.g. Tovstiga and Tulugurova, 2009). Furthermore, in various studies, different IC elements have emerged as the strongest performance drivers. The inconsistency of these findings confirms that there is as yet no clarity about how IC elements impact company performance indicators in these two countries. The conflicting results can be explained in terms of differences in sample settings, regional development levels, and methods employed (Cabrita and Bontis, 2008; F-Jardón and Martos, 2009; Sydler et al., 2014). These differences in methodology make direct comparison of existing findings problematic. Moreover, most of these studies used the VAIC method (Pulic, 2000), which has recently been much criticized for its inaccuracy in measuring IC (Ståhle et al., 2011). To empirically test potential contextual differences in the IC-performance relationship, the same methodology would need to be applied to both countries to enable a valid comparison, as well as more accurate measurement of IC. The present study addresses this need.

p.470

Research methods

Sampling and data collection

The study employed a survey research strategy. Data were collected during 2014, using a survey instrument that was targeted at firms in Russia and China with at least 100 employees. In China, data were collected from 139 firms, using both telephone interviews and an online survey. Most of those companies (81.1 per cent) were involved in manufacturing. They were located mostly in the province of Ningbo (66 per cent), followed by Shenzen (14 per cent). In Russia, data were collected from 86 companies, again using telephone interviews and an online survey. Most of the companies were located in St Petersburg (55 per cent) and Moscow (28 per cent). The sample included both manufacturing and service companies.

The key informant technique was utilized, meaning that one respondent per company provided responses to the survey. In China, the largest group of respondents (37 per cent), although familiar with their company’s knowledge-related issues, did not want to reveal their specific job title. The next largest groups of key informants were experts (29 per cent) and non-HR managers and directors (28 per cent). In Russia, most respondents (31 per cent) were experts, followed by HR managers and directors (24 per cent) and managing directors (21 per cent). Key descriptors of the surveyed companies are presented in Table 29.1.

Measures

The research instrument was a structured questionnaire, translated to Chinese and Russian from the original English version developed by Kianto, Inkinen, Ritala, and Vanhala under the auspices of Lappeenranta University of Technology, Finland, and previously reported in Inkinen, Kianto, et al. (2014) and Inkinen, Vanhala, et al. (2014), and Kianto, Gang, and Lee (2015) and Kianto, Saenz, and Arambaru (2015). Development of the scale was based on a thorough review of the literature and two pre-tests with Finnish datasets (N = 151 and N = 259). Research questionnaires were carefully translated to Mandarin Chinese and Russian languages by experts who were knowledgeable about the topic and fluent in both languages. This means that, content-wise, the research instrument was identical for all data collection locations.

Table 29.1 Descriptive statistics

p.471

The research instrument included statements to which the respondents reacted by means of a five-point Likert scale, anchored by I strongly agree/disagree. All key study variables were measured with composites comprising several items. For the independent variables, human capital items (3) were adapted from Bontis (1998) and Yang and Lin (2009). Structural capital items (3) were based on Kianto (2008a, 2008b) and Kianto et al. (2010), and the three relational capital items were taken from Kianto (2008a, 2008b). The dependent variable (company market performance) was taken from Delaney and Huselid (1996). Logarithms of company age and size were utilized as control variables. Survey instruments are available from the authors.

Findings

The first step of the analysis was to assess the functionality of the adopted measurement scales in the samples. As the scales had already been validated with larger samples, Cronbach’s α was utilized to assess the internal consistency of the scales. All scales returned alpha values above 0.7, indicating good internal consistency and validity. The means of all IC elements were assessed to be higher in Russian than in Chinese firms.

Next, correlations between study variables were calculated for each country sample. For both Russian and Chinese samples, all three IC elements were significantly correlated with market performance. As IC elements showed high inter-correlations with each other, variance inflation factor (VIF) scores were inspected for multicollinearity problems. As VIF scores were well below the cutoff point of 2.5, multicollinearity was not detected, and it was possible to proceed with the regression analyses. Full data tables of the scale reliabilities, descriptives, and correlations are available from the authors.

Finally, regression analyses were performed to test the impact of the different IC elements on organizational performance. Table 29.2 displays the results of the regression models for the two countries, indicating that in China, none of the three IC elements has a statistically significant impact on performance. However, structural capital comes very close to the threshold of significance at p = 0.055 and β-coefficient of 0.410. In China, 14 per cent of the variance in performance is explained. In Russia, only human capital has an impact on market performance, with a β-coefficient of 0.510. Structural capital and relational capital do not influence performance. Overall, the model explains 32 per cent of variation in organizational performance.

Table 29.2 Effect of elements of intellectual capital on company market performance

p.472

Discussion and conclusions

In this analysis of the impact of IC on organizational performance in Russia and China, it was found that in Russia, only human capital exerts a significant impact on firm performance. In China, only structural capital comes statistically close to impacting performance, but even here, the impact is very slight.

Only one of the several earlier studies of the Russian market (Garanina, 2011) identified human capital as the key IC element influencing company financial performance, assessing its impact as much higher than that of other elements of IC. At the same time, almost all the papers applying a VAIC approach found a positive relationship between human capital and financial performance indicators (Tovstiga and Tulugurova, 2007; Bayburina and Golovko, 2008; Bykova and Molodchik, 2011; Tomchuk et al., 2013), but the impact of HC on financial performance indicators differed little from that of other elements.

For Chinese companies, only structural capital was found to relate positively to performance indicators. This result echoes Chan (2009), whose studies of a sample of companies from the Hong Kong Hang Seng Index found that of all IC elements, only structural capital was positively related to ROA and ROE. Rather than national characteristics, a possible alternative explanation of structural capital’s role as the only near-significant predictor of performance in China is the large proportion (81 per cent) of manufacturing companies in the sample. This begs the question of whether industry-specific influences rather than national-level factors mainly determine IC’s impact on performance (Andreeva and Garanina, 2016).

Based on these findings, it seems that intangibles may indeed be of less relevance for the performance of firms in emerging economies, contrary to their importance for value creation in developed countries. Some of the available evidence suggests that the impact of IC on national economic wealth is higher in more developed countries (Ståhle et al., 2015); based on our findings, it seems that a similar contingency may also exist at firm level.

To our knowledge, this chapter is the first comparative analysis of IC management in emerging markets. The finding that IC impacts performance in different ways in Russia and China suggests that although emerging economies are sometimes grouped together, they should not be. The likelihood of fundamental institutional differences among emerging economies means that they should be examined individually rather than simplistically grouped together, with a view to identifying their idiosyncratic characteristics. The study contributes to the IC literature by furthering the emergent cross-cultural approach.

The literature review confirms the significant disparities among previous findings. At the same time, some similarities can be identified where the sample includes companies from the same industry, suggesting that the key elements of IC for financial performance vary by industry. For application to business, we propose that the focus on a particular element of IC should be based on the industry to which a company belongs.

For Russian managers, the general core implication is that human capital is a valuable resource that can improve financial performance indicators. According to Andreeva and Garanina (2016), this element was also important in improving financial performance indicators in manufacturing companies, although the significance of structural capital was higher. In summary, the results suggest that in Russian companies, human capital is a valuable resource for value creation that positively influences financial results, but in particular industries, other elements may prove more significant.

p.473

For the Chinese sample, the conclusions are less clear, as the obtained results align only with Chan (2009). Nevertheless, the Appendix invites the conclusion that structural capital is always a significant factor in value creation for Chinese companies. This means that Chinese managers should pay particular attention to internal structure, culture, business processes, and knowledge documentation and sharing systems to make their companies more competitive in the global economic environment.

As is commonly the case, this study has several limitations. First, only a limited number of companies were surveyed (86 in Russia and 139 in China). As both are vast countries with a sizeable population of firms, our results cannot be said to provide an overview of Russian or Chinese firms in general, but represent only a limited perspective on a group of firms in each country.

Second, the current study involved a subjective assessment of organization performance by the respondents rather than an evaluation based on some objective or external information. However, in Russia and China, it is difficult to acquire information about companies’ financial performance. Not all companies in these countries provide information about their performance to publicly accessible databases, and even if they do, the figures have to be regarded with caution. Additionally, the cross-sector nature of our research samples would have made it difficult to find more specific and targeted performance metrics that would at the same time be relevant for so wide a range of firms. For that reason, we had to be content with subjective assessments of firms’ generic market performance.

The limitations of this study suggest some fruitful avenues for future research. Several of these limitations relate to the nature of the data collected, involving subjective measures of performance, collected at the same time as the data on IC elements. Some prior research found that IC has a delayed effect on organizational performance (e.g. Väisänen et al., 2007). In combination with the long-term nature of relational capital, this finding suggests that this component of IC may still affect the performance of Russian and Chinese companies when studied over a longer time. This hypothesis can be tested in future studies, using time-lagged performance data. Further studies might also use objective performance measures, or a combination of subjective and objective, to investigate more comprehensively the link between IC and performance.

Extending the discussion about various measurement methods for IC (e.g. financial proxies versus surveys), future studies might incorporate both types of measures to compare their accuracy in measuring IC components, as well as their value as predictors of organizational performance.

One further interesting direction would be to explore the specifics of the different sectors or industries in greater detail – for example, the nature of the link between IC elements and performance in service firms. One can hypothesize that human capital might be expected to have the strongest impact in this sector (e.g. Kianto et al., 2010). Or again, how would IC elements link to performance in telecom companies? In this sector, we can hypothesize that relational capital may have the strongest impact (e.g. Garanina, 2011). Extending such arguments to other sectors can contribute to a more nuanced understanding of the role of IC, so increasing efficiency of management. In conclusion, aligning with May and Stewart (2013), we believe that extending the inquiry to other emerging economies as diverse institutional and cultural contexts will contribute to further development of IC theories.

p.474

Appendix 1. Empirical studies of the relationship between IC elements and firm performance in Russian and Chinese companies

p.475

Notes:

HC = human capital

RC = relational capital

SC = structural capital

++ = a strong positive relationship was found, identified as having higher coefficients in the model compared to other variables

+ = a positive relationship was found

− = a negative relationship was found

no = no relationship was found

n/a = data not available as this element was not included in the model

p.476

Note

1 The Economist (2008), “People for growth: The talent challenge in emerging markets. A report from the Economist Intelligence Unit”, available from: http://graphics.eiu.com/upload/People_for_growth.pdf (accessed 15 October 2015).

References

Andreeva, T. and Garanina, T. (2016), “Do all elements of intellectual capital matter for organizational performance? Evidence from Russian context”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 17, No. 2, pp. 397–412.

Andreeva, T. and Ikhilchik, I. (2011), “Applicability of the SECI Model of Knowledge Creation in Russian cultural context: Theoretical analysis”, Knowledge and Process Management, Vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 56–66.

Backman, M. (2001), Asian Eclipse, Exposing the Dark Side of Business in Asia, John Wiley, Singapore.

Barney, J. (1991), “Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage”, Journal of Management, Vol. 17, No. 1, pp. 99–120.

Bayburina, E. R. and Golovko, T. V. (2008), “The empirical research of the intellectual value of the large Russian companies and the factors of its growth”, Journal of Corporate Finance Research, Vol. 2, No. 6, pp. 5–19.

Bershidsky, L. (2016), “Russia is not dying from a brain drain”, Bloomberg, available at: www.bloomberg.com/view/articles/2016-07-06/russia-is-not-dying-from-a-brain-drain (accessed 1 July 2016).

Bontis, N. (1998), “Intellectual capital: An exploratory study that develops measures and models”, Management Decision, Vol. 36, No. 2, pp. 63–76.

Bykova, A. A. and Molodchik, M. A. (2011), “The influence of intellectual capital on companies’ performance indicators” vestnik SPbGU, Serija Menedzhment, Vol. 1, pp. 27–55.

Cabrita, M. D. R. and Bontis, N. (2008), “Intellectual capital and business performance in the Portuguese banking industry”, International Journal of Technology Management, Vol. 43, Nos 1–3, pp. 212–237.

Chan, K. H. (2009), “Impact of intellectual capital on organisational performance”, The Learning Organization, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 22–39.

Chang, S. C. and Lee, M. S. (2007), “The effects of organizational culture and knowledge management mechanisms on organizational innovation: An empirical study in Taiwan”, The Business Review, Cambridge, Vol. 7, No. 1, pp. 295–301.

Chen, J., Zhao, X., and Wang, Y. (2015), “A new measurement of intellectual capital and its impact on innovation performance in an open innovation paradigm”, International Journal of Technology Management, Vol. 67, No. 1, pp. 1–25.

Chen, J., Zhu, Z., and Xie, H. Y. (2004), “Measuring intellectual capital: A new model and empirical study”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 5, No. 1, pp. 195–212.

Chu, S. K. W., Chan, K. H., and Wu, W. W. Y. (2011), “Charting intellectual capital performance of the gateway to China”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 12, No. 2, pp. 249–276.

Delaney, J. and Huselid, M. A. (1996), “The impact of human resource management practices on perceptions of organizational performance”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 39, No. 4, pp. 949–969.

Dierickx, I. and Cool, K. (1989), “Asset stock accumulation and sustainability of competitive advantage”, Management Science, Vol. 35, No. 12, pp. 1504–1511.

Dittrich, M., Giljum, S., Polzin, C., Lutter, S., and Bringezu, S. (2011), “Resource use and resource efficiency in emerging economies: Trends over the past 20 years”, available from: http://seri.at/wpcontent/uploads/2011/03/SERI_WorkingPaper12.pdf (accessed 20 October 2015).

Domcheva, E. (2014), “Not the right people [online]”, Rossijskaja gazeta – Federal’nyj vypusk, 6422 (150). Available from https://rg.ru/2014/07/08/kadri.html (accessed 1 July 2016).

Dumay, J. (2013), “The third stage of IC: Towards a new IC future and beyond”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 5–9.

Dumay, J. and Garanina, T. (2013), “Intellectual capital research: A critical examination of the third stage”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 14, No. 1, pp. 10–25.

Dumay, J. and Guthrie, J. (2012), “IC and strategy as practice: A critical examination”, International Journal of Knowledge and Systems Science, Vol. 3, No. 4, pp. 28–37.

p.477

Edvinsson, L. (1997), “Developing intellectual capital at Skandia”, Long Range Planning, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 366–373.

Edvinsson, L. and Malone, M. (1997), Intellectual Capital: Realising Your Company’s True Value by Finding Its Hidden Brainpower, Harper Collins, New York.

Elenkov, D. S. (2002), “Effects of leadership on organizational performance in Russian companies”, Journal of Business Research, Vol. 55, No. 6, pp. 467–480.

Farrell, D. and Grant, A. J. (2005), “China’s looming talent shortage”, McKinsey Quarterly, available at: www.mckinsey.com/mgi/overview/in-the-news/looming-talent-shortage-in-china (accessed 1 July 2016).

F-Jardón, C. M. and Martos, M. S. (2009), “Intellectual capital and performance in wood industries of Argentina”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 10, No. 4, pp. 600–616.

Frietsch R. and Wang, J. (2007), “Intellectual property rights and innovation activities in China: Evidence from patents and publications”, available from: www.isi.fraunhofer.de/isi-wAssets/docs/p/de/diskpap_innosysteme_policyanalyse/discussionpaper_13_2007.pdf (accessed 1 July 2016).

Garanina, T. (2011), “Intellectual capital structure and value creation of a company: Evidence from Russian companies”, Open Journal of Economic Research, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 22–34.

Gurkov, I. (1996), “Changes of control and business reengineering in Russian privatized companies”, International Executive, Vol. 38, Vol. 3, pp. 359–388.

Gurkov, I., Zelenova, O., and Saidov, Z. (2012), ”Mutation of HRM practices in Russia: An application of CRANET methodology, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 23, No. 7, pp. 1289–1302.

Guthrie, J., Ricceri, F., and Dumay, J. (2012), “Reflections and projections: A decade of intellectual capital accounting research”, The British Accounting Review, Vol. 44, No. 2, pp. 68–92.

Hallén, L. and Johanson, M. (2004), “Integration of relationships and business network development in the Russian transition economy”, International Marketing Review, Vol. 21, No. 2, pp. 158−171.

Hamilton, G. G. (1996), Asian Business Networks, Walter de Gruyter, Hong Kong.

Holt, D. H., Ralston, D. A., and Terpstra, R. H. (1994), “Constraints on capitalism in Russia: The managerial psyche, social infrastructure, and ideology”, California Management Review, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 124–141.

Huang, Q., Davison, R. M., and Gu, J. (2008), “Impact of personal and cultural factors on knowledge sharing in China”, Asia Pacific Journal of Management, Vol. 25, No. 3, pp. 451–471.

Huber, P. and Wörgötter, A. (1998), Political Survival or Entrepreneurial Development? Observations on Russian Business Networks Location: Global, Area, and International Archive, available from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/5z5633ts (accessed 1 July 2016).

Hutchings, K. and Michailova, S. (2004), “Facilitating knowledge sharing in Russian and Chinese subsidiaries: The role of personal networks and group membership”, Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 8, No. 2, pp. 84–94.

Hutchings, K. and Michailova, S., (2006), “The impact of group membership on knowledge sharing in Russia and China”, International Journal of Emerging Markets, Vol. 1, No. 1, pp. 21–34.

Hutchings, K. and Weir, D. (2006), “Guanxi and Wasta: A comparison”, Thunderbird International Business Review, Vol. 48, No. 3, pp. 141–156.

Inkinen, H., Kianto, A., Vanhala, M., and Ritala, P. (2014), “Intellectual capital and performance–Empirical findings from Finnish firms”, paper presented to the International Forum on Knowledge Asset Dynamics (IFKAD), 11–13 June, Matera, Italy.

Inkinen, H., Vanhala, M., Ritala, P., and Kianto, A. (2014), ”Assessing measurement invariance of intellectual capital”, paper presented to the 10th EIASM Interdisciplinary Workshop on Intangibles, Intellectual Capital and Extra-Financial Information, 18–19 September, Ferrara, Italy.

Jansson, H. and Ramström, J. (2005), “Facing the Chinese business network in Southeast Asian markets: Overcoming the duality between Nordic and Chinese business networks”, paper presented to the 21st Annual IMP Conference, Erasmus University, Rotterdam. Available from: www.impgroup.org/uploads/papers/4705.pdf.

Jansson, H., Johanson, M., and Ramström, J. (2007), “Institutions and business networks: A comparative analysis of the Chinese, Russian, and West European markets”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 36, pp. 955–967.

Jiacheng, W., Lu, L., and Francesco, C. A. (2010), “A cognitive model of intra-organizational knowledge-sharing motivations in the view of cross-culture”, International Journal of Information Management, Vol. 30, No. 3, pp. 220–230.

p.478

Johnson, R. and Soenen, L. (2003), “Indicators of successful companies”, European Management Journal, Vol. 21, No. 3, pp. 364–369.

Kianto A. (2008a), “Assessing organisational renewal capability”, International Journal of Innovation and Regional Development, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 115–129.

Kianto, A. (2008b), “Development and validation of a survey instrument for measuring organizational renewal capability”, International Journal of Technology Management, Vol. 42, Nos 1–2, pp. 69–88.

Kianto, A., Andreeva, T., and Pavlov, Y. (2013), “The impact of intellectual capital management on company competitiveness and financial performance”, Knowledge Management Research and Practice, Vol. 11, No. 2, pp. 112–122.

Kianto, A., Gang, L., and Lee, R. (2015), “Knowledge management practices, intellectual capital and firm performance: Empirical evidence from Chinese companies”, paper presented to the European Conference on Knowledge Management (ECKM), 3–4 September, Udine, Italy.

Kianto, A., Hurmelinna-Laukkanen, P., and Ritala, P. (2010), “Intellectual capital in service and product-oriented companies”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 11, No. 3, pp. 305–325.

Kianto, A., Saenz, J., and Aramburu, N. (2015), “Knowledge-based human resource practices, intellectual capital and innovation”, paper presented to the EIASM 30th Workshop on Strategic Human Resource Management, 8–10 April. Brussels, Belgium.

Li, H. and Atuahene-Gima, K. (2001), “Product innovation strategy and the performance of new technology ventures in China”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 44, No. 6, pp. 1123–1134.

Lin, Y. and Dalkir, K. (2010), “Factors affecting KM implementation in the Chinese community”, International Journal of Knowledge Management, Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 1–22.

Liu, X. L. and White, S. (2001), “Comparing innovation systems: A framework and application to China’s transitional context”, Research Policy, Vol. 30, No. 7, pp. 1091–1114.

Lu, W. M., Wang, W. K., and Kweh, Q. L. (2014), “Intellectual capital and performance in the Chinese life insurance industry”, Omega, Vol. 42, pp. 65–74.

May, R. C. and Stewart, W. H. (2013), “Building theory with BRICs: Russia’s contribution to knowledge sharing theory”, Critical Perspectives on International Business, Vol. 9, Nos 1–2, pp. 147–172.

McCarthy, D., Puffer, S. M., Dunlap-Hinkler, D., and Jaeger, A. (2012), “A stakeholder approach to the ethicality of BRIC: Firm managers’ use of favors”, Journal of Business Ethics, Vol. 109, pp. 27–38.

Michailova, S. (2011), “Contextualizing in international business research: Why do we need more of it and how can we be better at it?” Scandinavian Journal of Management, Vol. 27, No. 1, pp. 129–139.

Michailova, S. and Husted, K. (2003), “Knowledge-sharing hostility in Russian firms”, California Management Review, Vol. 45, No. 3, pp. 59–77.

Michailova, S. and Hutchings, K. (2006), “National cultural influences on knowledge sharing: A comparison of China and Russia”, Journal of Management Studies, Vol. 43, No. 3, pp. 383–405.

Michailova, S. and Worm, V. (2003), “Personal networking in Russia and China: Blat and Guanxi”, European Management Journal, Vol. 21, No. 4, pp. 509–519.

Molodchik M. and Nursubina J. S. (2012) “Innovations and intellectual capital of a company: The analysis of panel data”, V sbornike: Sovremennye strategii innovacionnogo razvitija. Trinadcatye Drukerovskie chtenija, Pod redakciej R.M. Nizhegorodceva, Novocherkassk, Russia, pp. 231–237.

Molodchik, M., Shakina, E., and Barajas, A. (2014), “Metrics for the elements of intellectual capital in an economy driven by knowledge”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 15, No. 2, pp. 206–226.

Nahapiet, J. and Ghoshal, S. (1998), “Social capital, intellectual capital and the organizational advantage”, Academy of Management Review, Vol. 23, No. 2, pp. 242–266.

Petty, R. and Guthrie, J. (2000), “Intellectual capital literature review: Measurement, reporting and management”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 1, No. 2, pp. 155–176.

PricewaterhouseCoopers (2014), “A new vision for growth: Key trends in human capital”, available from: www.pwc.com/gx/en/hr-management-services/pdf/pwc-key-trends-in-human-capital-2014.pdf (accessed 15 October 2015).

Puffer, S. M. and McCarthy, D. J. (2011), “Two decades of Russian business and management research: An institutional theory perspective”, Academy of Management Perspectives, Vol. 25, No. 2, pp. 21–36.

Pulic, A. (2000), VAIC: An accounting tool for IC management”, International Journal of Technology Management, Vol. 20, Nos 5–8, pp. 702–714.

Puntillo, P. (2009), “Intellectual capital and business performance: Evidence from Italian banking industry”, Journal of Corporate Finance Research, Vol. 4, No. 12, pp. 96–115.

Ramström, J. (2005), West Meets East. Managing Cross-institutional Business Relationships with Overseas Chinese, Doctoral dissertation, Åbo Akademi University Press, Åbo, Finland.

p.479

Ricceri, F. (2008), Intellectual Capital and Knowledge Management: Strategic Management of Knowledge Resources, Routledge, London.

Salmi, A. (1996), “Russian networks in transition: Implications for managers”, Industrial Marketing Management, Vol. 25, No. 1, pp. 37–45.

Ståhle, P., Ståhle, S., and Aho, S. (2011), “Value added intellectual coefficient (VAIC): A critical analysis”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 531–551.

Ståhle, P., Ståhle, S., and Lin, C. (2015), “Intangibles and national economic wealth – A new perspective on how they are linked”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 16, No. 1, pp. 20–57.

Stewart, T. (1997), Intellectual Capital: The New Wealth of Organizations, Doubleday, New York.

Sun, Y. (2000), “Spatial distribution of patents in China”, Regional Studies, Vol. 34, No. 5, pp. 441–454.

Sveiby, K. E., (1997), The New Organizational Wealth: Managing and Measuring Knowledge Based Assets, Berrett Koehler, San Francisco, CA.

Sydler, R., Haefliger, S., and Pruksa, R. (2014), “Measuring intellectual capital with financial figures: Can we predict firm profitability?” European Management Journal, Vol. 32, No. 2, pp. 244–259.

Tomchuk, D., Perskij, Ju., and Sevodina, V. (2013), “Intellectual capital and return: Characteristics and evaluation”, Resursy, informacija, snabzhenie, konkurencija, Vol. 2, pp. 330–334.

Tovstiga, G. and Tulugurova, E. (2007), “Intellectual capital practices and performance in Russian enterprises”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 8, No. 4, pp. 695–707.

Tovstiga, G. and Tulugurova, E. (2009), “Intellectual capital practices: A four-region comparative study”, Journal of Intellectual Capital, Vol. 10, No. 1, pp. 70–80.

Tseng, C. Y. and Goo, Y. J. (2005), “Intellectual capital and corporate value in an emerging economy: Empirical study of Taiwanese manufacturers”, R&D Management, Vol. 35, No. 2, pp. 187–201.

Tung, R. L., (2007), “The human resource challenge to outward foreign direct investment aspirations from emerging economies: The case of China”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 18, No. 5, pp. 868–889.

Väisänen, J., Kujansivu, P., and Lönnqvist, A. (2007), “Effects of intellectual capital investments on productivity and profitability”, International Journal of Learning and Intellectual Capital, Vol. 4, No. 4, pp. 377–391.

Wang, D. and Chen, S. (2013), “Does intellectual capital matter? High-performance work systems and bilateral innovative capabilities”, China International Journal of Manpower, Vol. 34, No. 8, pp. 861–879.

Wang, L. (2004), “Intellectual property protection in China”, International Information and Library Review, Vol. 36, No. 3, pp. 251–263.

Wang, Z., Wang, N., and Liang, H. (2014), “Knowledge sharing, intellectual capital and firm performance”, Management Decision, Vol. 52, No. 2, pp. 230–258.

Wong, Y. H. and Tam, J. L. M. (2000), “Mapping relationships in China: Guanxi dynamic approach”, Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, Vol. 15, No. 1, pp. 57−70.

Wu, W. Y., and Tsai, H. J. (2005), “Impact of social capital and business operation mode on intellectual capital and knowledge management”, International Journal of Technology Management, Vol. 3, Nos 1–2, pp. 147–171.

Xiao, Y. (2013), “Research of the effectiveness of the growth of SMEs under intellectual capital driven-based on the empirical analysis of SMEs in China listed companies”, Information Technology Journal, Vol. 12, No. 20, pp. 5669–5672.

Yang, C. and Lin, C. (2009), “Does intellectual capital mediate the relationship between HRM and organizational performance? Perspective of a healthcare industry in Taiwan”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 20, No. 9, pp. 1965–1984.

Yeh, Y. J., Lai, S. Q., and Ho, C. T. (2006), “Knowledge management enablers: A case study”, Industrial Management and Data Systems, Vol. 106, No. 6, pp. 793–810.

Zeng, S. X., Shi, J. J., and Lou, G. X. (2007), “A synergetic model for implementing an integrated management system: An empirical study in China”, Journal of Cleaner Production, Vol. 15, No. 18, pp. 1760–1767.

Zhao, S. (2008), “Application of human capital theory in China in the context of the knowledge economy”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 19, No. 5, pp. 802–817.

Zhu, C. J., Cooper, B., De Cieri, H., Thomson, S. B., and Zhao, S. (2008), “Devolvement of HR practices in transitional economies: Evidence from China”, International Journal of Human Resource Management, Vol. 19, No. 5, pp. 840–855.