After the grapes are picked, they must be fermented. This is a delicate operation which must be carried out carefully, observing very strict standards, or the wine will oxidate and go bad. The rule of paramount importance which cannot be stressed enough is hygiene, because wine in the process of fermenting is very sensitive to bacteria.

The phenomenon of fermentation has been scientifically understood for at least a century and a half, thanks to research done by Louis Pasteur. He was the first to conclude that the fermentation of wine was a result of the action of yeasts. With Pasteur’s fantastic discovery, it was finally possible to comprehend and to master the chemical process that occurs during the fermentation of wine.

Essential in making wine, yeasts are living one-cell organisms which reproduce spontaneously. The most appropriate yeasts for winemaking belong to the Saccharomyces family, which includes the yeasts used for baking bread and brewing beer.

If it is true that yeasts are found naturally on the surface of the grape, it is not true that they arise spontaneously: these micro-organisms are borne through the air and settle on the grapes. They are also carried onto the grapes by the insects that come to gather nectar from the vines.

Yeasts cannot be created synthetically. It is possible, however, to cultivate them in the laboratory, and to stimulate their reproduction, resulting in large quantities of yeast.

More than 2000 species of yeast are known. They are classified by their form (round or oval) and by their specific properties. Yeasts that are appropriate for winemaking are oval, round, or elliptical.

Wine yeasts feed on sugar (saccharose). When it is absorbed by the yeast, sugar is transformed into alcohol and carbon dioxide. Depending on the type of yeast, this process also gives forth chemical byproducts (considered waste) which are not always desirable in the transformation of the must into wine. Some yeasts give the wine a bad taste. This is why it is necessary to use only wine yeasts and to avoid others, particularly bread yeast.

Yeasts cells under the microscope.

Moreover, the acetobacters deposited by fruit flies can cause an acerbic astringency which makes the wine taste like vinegar. Metabisulphite kills the bacteria and allows the appropriate yeasts to restart fermentation; the next chapter will give more details on this.

Scientific progress has allowed the development of selected yeasts in the laboratory according to the type of wine to be produced. However, we shouldn’t delude ourselves: the properties of yeasts are completely unrelated to particular grape varieties. They only serve in the pursuit of specific goals that the wine-maker has in mind. Certain yeasts produce higher degrees of alcohol than others (many yeasts die or become inactive when the alcoholic content reaches 14 percent or 28 degrees Proof). Other yeasts possess distinctive properties which can be exploited to advantage by knowledgeable amateur vintners.

To give an example: if you intend to make a wine for drinking young, a 71B-1122 yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae) is recommended, because it will rapidly bring out the intrinsic qualities of your wine. On the other hand, if you want to make a sparkling wine, it is advised to use EC-1118 (Saccharomyces bayanus): this yeast tolerates a high degree of alcohol and is therefore more suitable for making sparkling wines. Finally, the K1-V1116 type of yeast is used very often for red wines: it has the ability to absorb all the oxygen in the wine during its reproductive phase, thus asphyxiating the wild yeasts that might be present.

The EC-1118 type is a resistant yeast and one of the most popular.

About forty types of wine yeasts are now produced, sufficient for the needs of both the industry and the amateur winemaker. The world leader in this domain is Lallemand & Co., with its head office in Montreal.

During laboratory experiments, it was also discovered that certain yeasts adapt better to variations in the alcohol content of wine as they pass from one generation to another. The first generation may live quite comfortably with a specific gravity of 1.0701 while the following generation is more comfortable with a specific gravity of 1.050 and a higher alcohol content, and so forth.

In general, it is the rise in alcohol content that puts a stop to the fermentation. Therefore, it is recommended to carry out a first racking when a specific gravity reading of 1.020 is obtained. This is the critical moment: the carbon dioxide produced by the yeast is partly imprisoned within the must, inhibiting its activity; also, millions of yeast cells have died and are deposited at the bottom of the carboy. This first racking not only cleans out the accumulated impurities, but oxygenizes the must and releases the excess carbon dioxide, so that the yeast, placed in a more propitious environment for its development, will recommence its alcohol-producing activity until the desired specific gravity measurement is reached.

If by any mischance the fermentation does not start up again, restarter has to be made, that is, yeast has to be cultivated in another medium. The recipe for restarter can be found in Chapter 6.

Yeast Nutrients (or Energizer)

To increase the chances of successful fermentation, the elements necessary for the yeast to proliferate must be provided. Besides the glucids that are transformed during the fermentation process, the yeast needs to assimilate mineral substances. These mineral substances are the yeast’s food and basic vitamins. Among the mineral elements essential for the yeast cells to multiply are potassium, sodium, calcium, magnesium, iron, phosphorus, sulphur and silicium. Yeast also needs, in much lesser quantities, the following oligo-elements: aluminum, bromine, chromium, copper, lead, manganese and zinc, as well as vitamins B, B1, and C.

Normally, all the minerals and vitamins named above are present in sufficient quantities in the fresh must. However, it was observed that the addition of phosphate, potassium and magnesium leads to a more rapid, vigorous and successful fermentation.

Adding yeast nutrients is strongly recommended when using concentrated and pasteurized musts.

On the other hand, in the case of concentrated or pasteurized must, a high proportion of the vitamins have been destroyed in the sterilization process, and therefore it is strongly recommended to add yeast nutrients.

Over the last fifty years or so, laboratory research has led to enormous advances in the science of oenology. Today, fermentation is no longer a miraculous, hit-or-miss operation. It can now be controlled up to a certain point, and it is a very rare occurence for a winemaker to run up against serious problems during the fermentation stage, for the very good reason that every effort has been made to develop sure-fire, effective yeasts (and to modulate the whole of the fermentation process). The use of selected cultured yeasts has become the sine qua non of home winemakers, except for a few die-hard individualists who prefer to remain at the mercy of Mother Nature. In this case, it is far better to trust in science, which has given us a natural product which always works.

It is true that the grape harbours bacteria transmitted by the soil, the air, rain, as well as by flies and other insects. These bacteria are extremely important in the transformation of the must, as well as for the taste of the wine; however, they can also have a hand in spoiling it. Some bacteria are good for wine, while others ruin it.

The bacteria that play an essential positive role in the fermentation process are the malolactic bacteria. They are able to transform malic acid (which naturally has a very acidic taste) into milder lactic acid and volatile carbonic acid. This process, called malolactic fermentation, takes place after the alcoholic (also called primary, or aerobic) fermentation stage. In the warmer wine-producing regions, it begins almost immediately after this stage, while in the cooler production regions of France and Germany, for example, it may only begin six months later, as low winter temperatures prevent malolactic fermentation from occurring.

In earlier times, popular belief attributed qualities to wine that corresponded to the life of plants: it was said that wine underwent a “rising of the sap” in the springtime, which explained the action observed in the vats or the casks. In fact, the higher air temperature induces this fermentation stage. The arrival of spring, particularly in temperate climates, activates the malolactic bacteria which make the wine cloudy and bring about the chemical process described above.

It is important to know that the question of malolactic fermentation need only concern winemakers who are using whole grapes or unsterilized must (fresh refrigerated must). Those who bug pasteurized or concentrated must do not have to worry about it: malolactic fermentation will not take place, because all the bacteria are killed by heat during pasteurization and in the concentration process. Note also that certain musts classified as “natural” or “pure” are actually reconstituted from concentrates2 and they will not necessarily undergo malolactic fermentation. To know the exact nature of the must you are buying, you should read the label thoroughly, or ask your retailer about it.

Malolactic fermentation reduces the wine’s acidity. Therefore, it is desirable in the case of red wines (naturally acidic and often tannic) as it makes them smoother and more supple, but is less desirable in the case of whites, which may lose some of their crispness and natural liveliness.

The rules are not that simple, however. Some white wines, Chardonnay for example, benefit from malolactic fermentation, whereas Riesling and Chenin Blanc lose in the bargain, even though both have a high acidity to begin with.

Thus, malolactic fermentation is an optional process which comes into play in the more complex aspects of winemaking. It can be encouraged or prevented, depending on the final result desired by the winemaker, irrespective of natural acidity rates.

It can be artificially induced by adding malolactic bacteria right after the primary (alcoholic) fermentation stage when the sugar index has greatly decreased, which is the most propitious moment for this type of bacteria to multiply. The wine’s temperature must also be warmed to at least 20°C (68°F); if not, malolactic fermentation may stop altogether, or still worse, may occur later on, when the wine is already bottled. The malolactic fermentation stage varies between 2 and 12 weeks in length.

Inoculation with malolactic bacteria may be necessary when too much metabisulphite has been used after picking the grapes, killing most of the bacteria. This operation must be done with great care.

It is possible to know if malolactic fermentation has taken place in a particular wine simply by sending a sample to a laboratory for a chromatography reading of the amounts of malic and lactic acids in the wine. When this analysis is done, the winemaker can take steps to prevent the malolactic bacteria from attacking the tartaric acids later on; when that happens, the wine changes colour, becomes dull-looking, and has a taste that makes it only fit to throw out. Amateur winemakers who press their own grapes have often suffered the dire consequences of this phenomenon.

The best way to avoid unpleasant surprises is to keep the wine at a temperature of 20°C (68°F) for a period of two or three months. This can be done in two ways: by heating the room to the desired temperature, or by using heating belts around the containers if the wine is stored in a cold room or in a cool basement. At the end of that period, we advise adding a level quarter-teaspoon of potassium metabisulphite which has been dissolved in lukewarm water (or three Campden tablets of sulphur dioxide made from potassium metabisulphite) to every 20 or 23 litres of must.3

Malolactic fermentation is not recommended for wine to be drunk young. The best way to prevent unwanted malolactic fermentation is to sulphite the wine after the alcoholic fermentation stage. Simply add the same level quarter-teaspoon of potassium metabisulphite previously dissolved in water (or three Campden tablets) to each 20- or 23-litre vat, and the problem will be solved.

The amateur should be aware that wineries do not proceed in the same manner in the fermentation of red wine as they do in the case of white.

When the harvested grapes are rushed to the fermenting rooms, the resident oenologist quickly carries out analyses to verify the quality of the grapes, and makes corrections to the situation by eliminating the fruit considered inappropriate for fermentation and by making chemical and/or physical adjustments.

The crushing of the grapes follows, with precautions to avoid grinding up the seeds, which would release too much tannin and oils harmful to the flavour of the wine.

The red grapes are then “destemmed”, or detached from their stems. Vintners used to keep part of the stalk to increase the amount of tannin in the wine, but today, the tendency is to eliminate it completely. The consensus is that the tannin contained in the seeds and the skin of the grapes is enough to balance the wine, and that the tannin in the stalk has a rather disagreeable, herbaceous flavour to it.

The industry has developed crusher-destemmers which do both operations at once. The skins are left in contact with the juice and the pulp, to pigment the must to the desired colour. This process also provides a convenient opportunity to inoculate the must with yeasts so that fermentation will begin as soon as possible. Fermentation is the best way to prevent oxidation. The cardon dioxide that it releases serves as a protective layer against the oxidating effects of the oxygen. Commercial wine production requires huge containers for this process; most industrial wineries opt for either concrete or stainless steel vats, some of which can hold up to 454,000 litres!

Crushing grapes at a large winery.

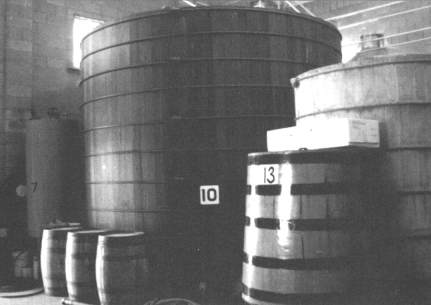

Primary fermentation takes about 21 days, but after seven to ten days, the wine is siphoned into smaller vats where it will age, protected from oxidation. The method varies according to the quantity of wine being made. Non-appellation wines are put into stainless steel vats smaller than the fermentors, often with oak chips to create the illusion (still fashionable today) that the wine has been aged in oak barrels. The appellation mineure wines are put into authentic oak vats that can hold an astonishing 10,000 litres each (over 2000 gallons!). The appellations supérieures have the privilege of going into 225-litre oak casks which, in the case of the best crus, are replaced every year to allow the wine to draw as many qualities as possible from the precious wood.

Oenologists at work among reservoirs with a capacity of 454,000 litres each (the equivalent of 100,000 gallons, or 600,000 bottles)!

In general, aging in oak casks lasts at least a year. During this time, more wine is added several times to make up for the quantity which has evaporated through the pores of the wood, in a process called “topping up.” The wine lost in this natural aging process is called la part des anges, or the “angels’ share” in French winemaking jargon.

Before bottling, the wine is cleared and stabilized. Clarification methods have evolved considerably since Roman times, when a technique called fining was first used. Fining consists of introducing various substances into the wine that will bring the particles that cloud the wine down to the bottom of the barrel. The “glues” that are still used for this today are all natural substances, including defibrinated ox blood, casein, gelatin, egg white and fish glue. This delicate method has been largely abandoned in favour of more expeditious ones, like clearing by centrifugal force. In the wine industry, this operation is done by a centrifuge pump that resembles a juice extractor, but with much more imposing dimensions. The wine is poured into a cylinder, then subjected to rotary action (up to 10,000 rotations/minute) which forces the impurities outward to the walls, which are self-cleaning. Freed from its clouding particles, and also from spent yeast cells, the wine instantly becomes limpid and clear. The centrifuge pump is normally used after primary fermentation has taken place. This prevents the proliferation of harmful bacteria; thus during filtration, which is done at a much later stage, the filters will be less clogged up.

Oak casks of different dimensions.

Over the last few decades, the practice of filtering wine through pads or cartridges (see Chapter 4) has increasingly come into favour. The wine passing through these types of filtering apparatus is completely cleared of suspended particles or sediment without losing any of its essential qualities.

Wine grapes ready for crushing.

When these operations are finished, it is the moment for blending the different varietals that the winemaker has available, if he or she chooses to do so. And finally, the wine is ready for bottling, maturing, and marketing. The vintner’s job is over, and the wine is now subject to the wine-lover’s pleasure!

The Fermentation of White Wine

The fermenting techniques for white wine are almost identical to those for red, with this main difference: the crushing and the pressing operations are done one after the other, so that the stems, seeds, and skins are separated from the must as rapidly as possible. The simple reason for this is that it prevents the wine from being coloured by the skins. The skins of white grapes tend to oxidate very quickly when they are separated from the pulp, and if they are not removed fast enough, they will give a brown colour to the must, impairing both colour and flavour of the final product.

Also, to intensify the flavour of white wines, they are subjected to cold fermentation. The temperature of the must is chilled as low as 8°C (46°F) to slow the fermentation process. This technique is practised on a large scale in the warm wine-producing regions of California, Australia and Italy, to give more flavour to the white wine (for fruity, or pear flavours) by prolonging the transformation of the sugar into alcohol and activating the effects that this longer process has upon the constitution of the must. Cold fermentation methods vary considerably. The most common industrial method is to put the must into huge stainless steel fermentors which have a double wall containing glycol or amonia as a coolant. Another method is to run cold water down the outside surface of the fermentor. In California, cold fermentation is done at temperatures varying between 12°C (54°F) and 14°C (57°F).

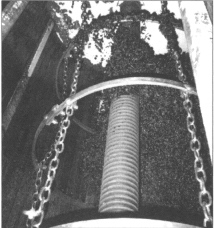

Industrial grape-pressing.

Carbonic maceration4 is a technique that was first used for red wine in the Beaujolais region many years ago, and which consists in leaving the uncrushed grapes to ferment in a closed vat. The weight of the upper layers of grapes upon those underneath leads to an accumulation of juice at the bottom of the vat, which ferments and produces carbon dioxide. Harking back to ancient times, the sugar is thus transformed into alcohol without adding yeast. Where the hand of modern technology comes in is with the artificial addition of more carbon dioxide to ensure that the vat is fully saturated with it, protecting the grapes from oxygen and allowing them to macerate on their own, for seven to twenty-one days. When the gas penetrates the pulp, it brings out the aroma and bouquet, and eliminates excess acidity thanks to the transformation of the malic acid. This allows the wine to be drunk younger, while also giving it a more distinctive flavour.

Engravings on oak wine casks.

Once the must has macerated, regular fermentation then occurs. Both the techniques of cold fermentation and carbonic maceration have met with great success. Humble Bordeaux appellations, for example, Sirius, Numéro 1 and Michel Lynch, have acquired a much better taste with carbonic maceration, and the sale of these products in North America has shot up. They are best consumed young, however, as the bouquet generated by this kind of fermentation is somewhat volatile and tends to fade with time. In fact, two years after bottling, there is hardly a hint of this distinctive bouquet left.

As for aging and bottling methods, the same rules apply to both red and white wines.

1. On density measurement, see the description of the hydrometer in Chapter 4.

2. See Chapter 5 for types of must.

3. For the equivalents in Imperial and U.S. measures, see Precision Test.

4. The type of fermentation is also called intracellular fermentation.