26 Tables and Figures

Many research papers use tables and figures to present data. Tables are grids consisting of columns and rows that present numerical or verbal facts by categories. Figures include charts, graphs, diagrams, photographs, maps, musical examples, drawings, and other images. All these types of tabular and nontextual materials are collectively referred to as illustrations (a term sometimes used interchangeably with figures) or graphics.

When you have data that could be conveyed in a table or figure, your first task is to choose the most effective of these formats; some kinds of data are better represented in a table, some in a chart, others in a graph. Your choice will affect how your readers respond to your data. These are rhetorical issues, discussed in chapter 8. This chapter focuses on how to construct the particular form you choose, looking specifically at tables and two types of figures—charts and graphs.

Most tables, charts, and graphs are now created with software. You cannot rely on software, however, to select the most effective format or to generate such items in the correct style, nor will software ensure logical or formal consistency. Expect to change some default settings before creating tables, charts, and graphs and to fine-tune these items once they are produced.

Your department or university may have specific requirements for formatting tables and figures, usually available from the office of theses and dissertations. If you are writing a class paper, check with your instructor for any special requirements. Review these requirements before you prepare your paper. They take precedence over the guidelines suggested here. For style guides in various disciplines, see the bibliography.

For more information on creating and formatting tables and figures and inserting them into your paper, see A.3.1.

26.1 General Issues

There are several issues common to the presentation of tables and figures in papers.

26.1.1 Position in the Text

Normally you should place a table or figure immediately after the paragraph in which you first mention it. Sometimes, however, such placement will cause a short table to break unnecessarily across the page or a figure to jump to the top of the next page, leaving more than a few lines of white space at the bottom of the previous page. To prevent either of these from happening, you may (a) place the table or figure farther along in the text, as long as it remains within a page of its first mention, or (b) place the table or figure just before the first mention, as long as it appears on the same page as the mention. (Such adjustments are best made after the text of your paper is final.)

You may group smaller tables or figures on a page, as long as they are clearly distinct from one another. Grouped tables generally retain their own titles (see 26.2.2). If grouped figures are closely related, give them a single number and a general caption; otherwise use separate numbers and captions (see 26.3.2). (Depending on your local guidelines, you may instead group tables and figures together in a section labeled Illustrations in the back matter of your paper; see A.2.3.1.)

If a table or figure is marginally relevant or too large to put in the text, put it in an appendix in the back matter of your paper (see A.2.3).

For more information on inserting tables and figures into your paper, see A.3.1.

26.1.2 Size

Whenever you can, format tables and figures to fit on one page in normal, or portrait, orientation. If they do not fit, try shortening long column heads or abbreviating repeated terms.

If you cannot make a table or figure fit on a page, you have several options.

■ Landscape. If a table or figure is too wide for a page, turn it ninety degrees so that the left side is at the bottom of the page; this orientation is called landscape or broadside. Do not put any text on a page containing a landscape table or figure. Set the table title or figure caption in either landscape or portrait orientation. See figure A.13 for an example. (You may need to convert a table into an image file in order to rotate it.)

■ Side by side. If a table is longer than a page but less than half a page wide, double it up and position the two halves side by side in one table on the same page. Separate the two halves with a vertical rule, and include the column heads on both sides.

■ Multiple pages. If a table or figure is too long to fit on a single page in portrait orientation or too wide to fit in landscape, divide it between two (or more) pages. For tables, repeat the stub column and all column heads (see 26.2) on every page. Omit the bottom rule on all pages except the last.

■ Reduction. If the figure is a photograph or other image, consider reducing it. Consult your local guidelines for any requirements related to resolution, scaling, cropping, and other parameters.

■ Separate items. If none of the above solutions is appropriate, consider presenting the data in two or more separate tables or figures.

■ Supplement. If the table or figure consists of material that cannot be presented in print form, such as a large data set or a multimedia file, treat it as an appendix, as described in A.2.3.

26.1.3 Source Lines

You must acknowledge the sources of any data you use in tables and figures that you did not collect yourself. You must do this even if you present the data in a new form—for example, you create a graph based on data originally published in a table, add fresh data to a table from another source, or combine data from multiple sources by meta-analysis.

Treat a source line as a footnote to a table (see 26.2.7) or as part of a caption for a figure (see 26.3.2). For tables, introduce the source line with the word Source(s) (capitalized, in italics, followed by a colon). If the source line runs onto more than one line, the runovers should be flush left, single-spaced. End a source line with a period.

If you are following bibliography style for your citations, cite the source as in a full note (see chapter 16), including the original table or figure number or the page number from which you took the data. Unless you cite this source elsewhere in your paper, you need not include it in your bibliography.

Source: Data from David Halle, Inside Culture: Art and Class in the American Home (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993), table 2.

Sources: Data from Richard H. Adams Jr., “Remittances, Investment, and Rural Asset Accumulation in Pakistan,” Economic Development and Cultural Change 47, no. 1 (1998): 155–73; David Bevan, Paul Collier, and Jan Gunning, Peasants and Government: An Economic Analysis (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989), 125–28.

If you are following author-date style for your citations, cite the source as in a parenthetical citation (minus the parentheses) and include full bibliographical information about it in your reference list (see chapter 18).

Source: Data from Halle 1993, table 2.

Sources: Data from Adams 1998, 155–73; Bevan, Collier, and Gunning 1989, 125–28.

If you have adapted the data in any way from what is presented in the original source, include the phrase adapted from in the source line, as shown in tables 26.1 and 26.3.

For photographs, maps, and other figures that you did not create yourself, include an acknowledgment of the creator in place of a source line.

Map by Gerald F. Pyle.

Photograph by James L. Ballard.

If your dissertation will be submitted to an external dissertation repository, you may also need to obtain formal permission to reproduce tables or figures protected by copyright. See chapter 4 of The Chicago Manual of Style, 16th edition (2010). If you need to include credit lines in connection with such permissions, see CMOS 3.28–36 (figures) and 3.74 (tables).

26.2 Tables

In many situations, you may choose to present data in a table. Chapter 8 describes criteria for using tables as well as general design principles for them. This section covers most of the issues you are likely to encounter in their preparation. Tables 26.1–26.3 provide examples of the principles discussed here.

Tables vary widely in the complexity of their content and therefore in their structure, but consistency both within and across tables is essential to ensure that readers will understand your data.

Use arabic numerals for all numerical data in tables unless otherwise noted. To save space, you can use abbreviations and symbols more freely than you can in text, but use them sparingly and consistently. If standard abbreviations do not exist, create your own and explain them either in a footnote to the table (see 26.2.7) or, if there are many, in a list of abbreviations in your paper’s front matter (see A.2.1).

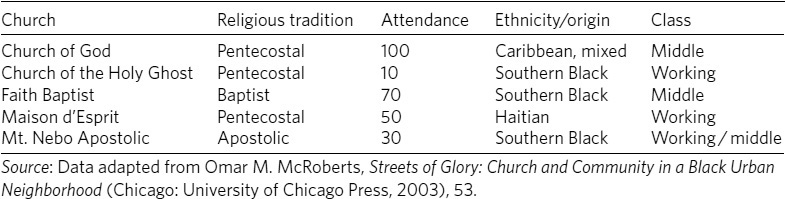

Table 26.1. Selected churches in Four Corners, Boston

Table 26.2. Election results in Gotefrith Province, 1950–60

Table 26.3. Unemployment rates for working-age New Yorkers, 2000

26.2.1 Table Structure

A table has elements analogous to horizontal and vertical axes on a graph. On the horizontal axis along the top are column heads. On the vertical axis along the left are headings that constitute what is called the stub column.

This grid of columns (vertical) and rows (horizontal) in a table usually correlates two sets of variables called independent and dependent. The independent variables are traditionally defined on the left, in the stub column. The dependent variables are traditionally defined in the column heads. If you include the same set of variables in two or more tables in your paper, be consistent: put them in the same place in each table, as column heads or in the stub.

The data, which may be words, numbers, or both (see table 26.1), are entered in the cells below the column heads and to the right of the stub column.

26.2.2 Table Numbers and Titles

In general, every table should have a number and a title. Place these items flush left on the line above the table, with the word Table (capitalized, in roman type), followed by the table number (in arabic numerals), followed by a period. After a space, give the title without a terminal period. Capitalize the title sentence style (see 22.3.1). If a title runs onto more than one line, the runovers should be flush left, single-spaced.

Table 13. Yen-dollar ratios in Japanese exports, 1995–2005

A simple tabulation that can be introduced clearly in the text, such as a simple two-column list, need not be numbered or titled.

Chicago’s population grew exponentially in its first century:

1840 | 4,470 |

1870 | 298,977 |

1900 | 1,698,575 |

1930 | 3,376,438 |

26.2.2.1 TABLE NUMBERS. Number tables separately from figures, in the order in which you mention them in the text. If you have only a few tables, number them consecutively throughout the paper, even across chapters. If you have many tables and many chapters, use double numeration: that is, the chapter number followed by a period followed by the table number, as in Table 12.4.

When you refer to a table in the text, specify the table number (“in table 3”) rather than its location (“below”) because you may end up moving the table while editing or formatting the paper. Do not capitalize the word table in text references to tables.

26.2.2.2 TABLE TITLES. Keep table titles short but descriptive enough to indicate the specific nature of the data and to differentiate tables from one another. For discussion of good titling practices, see 8.3.1. Table titles may be presented in a smaller typeface than the rest of your text.

26.2.3 Rules

Rules separate different types of data and text. Too many rules create a confusing image, so use them sparingly and consistently (see also 8.3.2).

■ Insert full-width horizontal rules to separate the title from the column heads (see 26.2.4), the column heads from the body of the table, and the body of the table from footnotes. A rule above a row of totals is traditional but not essential (see table 26.2). Unnumbered tables run into the text can usually be set with no rules, as long as any column heads are set off typographically.

■ Use partial-width horizontal rules to indicate which column heads and columns are governed by special types of heads, if you use them (see 26.2.4, table 26.2).

■ Leave enough space between data cells to avoid the need for additional rules. Do not use vertical rules to enclose the table in a box. But if you need to double up a long and narrow table (see 26.1.2), use a vertical rule to separate the two halves.

■ Use caution in employing shading or color to convey meaning (see 8.3.2). Even if you print the paper on a color printer or submit it as a PDF, it may be printed or copied later on a black-and-white machine, and if it is a dissertation, it may be microfilmed. Shading and color may not reproduce well in any of these forms. If you use shading, make sure it does not obscure the text of the table, and do not use multiple shades, which might not reproduce distinctly.

26.2.4 Column Heads

A table must have at least two columns, each with a head or heading at the top that names the data in the column below.

■ When possible, use noun phrases for column heads. Keep them short (or set them to wrap, as in table 26.1) to avoid an excessively wide table.

■ Capitalize column heads sentence style (see 22.3.1).

■ Align the stub head flush left (see 26.2.5); center other column heads over the widest entry in the column below. Align the bottom of all heads horizontally.

You may need to include special types of heads in addition to the column heads. Such a head may apply to two or more columns of data. Center the head over the relevant columns with a partial-width horizontal rule beneath (and, if necessary, above) it. Table 26.2 shows heads both above (“1950”) and below (“Provincial Assembly”) the column heads.

Heads may have explanatory tags to clarify or to indicate the unit of measure for data in the column below. Enclose such tags in parentheses. You may use abbreviations and symbols (mpg, km, lb., %, $M, and so on), but be consistent within and among your tables.

Responses (%)

Pesos (millions)

26.2.5 The Stub

The leftmost column of a table, called the stub, lists the categories of data in each row.

■ Include a column head for the stub whenever possible, even if it is generic (“Typical Characteristic” or “Variable”). Omit the head only if it would merely repeat the table title or if the categories in the stub are too diverse for a single head.

■ Make stub entries nouns or noun phrases whenever possible, and keep them consistent in form: “Books,” “Journal articles,” “Manuscripts,” rather than “Books,” “Articles published in journals,” “Manuscripts.” Use the same word for the same item in all of your tables (for example, if you use Former USSR in one table, do not use Former Soviet Union in another).

■ Capitalize all stub entries sentence style (see 22.3.1), with no terminal periods.

■ Set the stub head and entries flush left, and indent any runovers (as in table 26.1).

■ To show the sum of the numbers in a column, include an indented stub entry titled Total (see table 26.2).

If the stub column includes subentries as well as main entries (see table 26.3), distinguish them through indentation, italics, or both. Follow the same principles listed above for main entries for capitalization and so forth.

26.2.6 The Body of a Table

The body of a table consists of cells containing your data, which may be words, numbers, or both (see table 26.1).

If the data are numerical and all values in a column or in the entire table are in thousands or millions, omit the rightmost zeros and note the unit in an explanatory tag in the relevant column head (see 26.2.4), in the table title (26.2.2), or in a footnote (26.2.7). Indicate an empty cell with three spaced periods (ellipsis dots), centered as in table 26.3.

26.2.6.1 HORIZONTAL ALIGNMENT. Align the data in each row with the stub entry for that row.

■ If the stub entry runs over onto two or more lines but the related data does not, align the row with the bottom line of the stub entry (see the row beginning “Church of the Holy Ghost” in table 26.1).

■ If both the stub entry and the data run over onto two or more lines, align the row with the top line of the stub entry (see the row beginning “Mt. Nebo Apostolic” in table 26.1).

■ If necessary, insert leaders (lines of periods, or dots) to lead the reader’s eye from the stub to the data in the first column. (For an example of leaders in a similar context, see fig. A.5.)

26.2.6.2 VERTICAL ALIGNMENT. Align a column of numbers vertically on their real or implied decimal points, so that readers can compare the values in the column. If all numerical values in a column have a zero before a decimal point, you may omit the zeros (see fig. A.13).

Align dollar signs, percent signs, degrees, and so on. But if they occur in every cell in the column, delete them from the cells and give the unit as a tag in the column head (see 26.2.4, table 26.2, and fig. A.13).

If the data consist of words, center each column under the column head. If any items have runovers, align each column flush left (see table 26.1).

26.2.7 Footnotes

If a table has footnotes, position them flush left, single-spaced. Leave a blank line between the bottom rule of the table and the first note, and also between notes. Footnotes may be presented in a smaller typeface than the rest of the text; consult your local guidelines.

Footnotes for tables can be of four kinds: (1) source lines (discussed in 26.1.3), (2) general footnotes that apply to the whole table, (3) footnotes that apply to specific parts of the table, and (4) notes on levels of statistical significance. If you have more than one kind of note, put them in that order.

26.2.7.1 GENERAL NOTES. General notes apply to the entire table. They define abbreviations, expand on the table title, specify how data were collected or derived, indicate rounding of values, and so on. Gather all such remarks into a single note. Do not put a note number (or other symbol) anywhere in the table or the table title, or with the note itself. Simply begin the note with the word Note (capitalized, in italics, followed by a colon). See also table 26.3.

Note: Since not all data were available, there is disparity in the totals.

26.2.7.2 SPECIFIC NOTES. Notes to explain specific items in a table can be attached to any part of the table except the table number or title. Designate such notes with lowercase superscript letters rather than numbers, both within the table and in the note itself. Do not begin the note with the word note but with the same superscript letter, with no period or colon following.

a Total excludes trade and labor employees.

If you include more than one such note in a table (as in table 26.2), use letters in sequential order, beginning at the upper left of the table, running left to right and then downward, row by row. If a note applies to two or more items in the table, use the same letter for each item; if it applies to all items in a column or row, put the letter in the relevant column head or stub entry.

26.2.7.3 NOTES ON STATISTICAL SIGNIFICANCE. If you include notes on the statistical significance of your data (also called probability notes), and if the significance levels are standard, designate notes with asterisks, both within the table and in the note itself. Use a single asterisk for the lowest level of probability, two for the next higher, and three for the level after that. If, however, you are noting significance levels other than standard ones, use superscript letters instead. Because these footnotes are short and they share a single purpose, you may combine them on the same line, spaced, without intervening punctuation. The letter p (for probability, no period after it) should be lowercase and italic. Omit zeros before decimal points (see 23.1.3).

*p < .05

**p < .01

***p < .001

26.3 Figures

The term figure refers to a variety of images, including charts, graphs, diagrams, photographs, maps, musical examples, and drawings. Most such materials can now be prepared and inserted into a paper electronically. The technical details are software-specific and too complex to be covered in this book, but some general guidelines are presented in A.3.1.

This section describes some principles for presenting two types of figures created from data: charts and graphs. It also discusses captions for figures of all kinds.

Treat a video, an animation, or any other multimedia file that cannot be presented in print form as an appendix (see A.2.3).

26.3.1 Charts and Graphs

In many situations you may choose to present data in a chart or graph. Chapter 8 lays out criteria for using these graphic forms as well as general design principles for them. It also provides examples of several different types of graphics. For detailed guidance on constructing charts and graphs, consult a reliable authority.

Each chart and graph in your paper should take the form that best communicates its data and supports its claim, but consistency both within and across these items is essential to ensure that readers will understand your data. Keep in mind the following principles when presenting charts and graphs of any type:

■ Represent elements of the same kind—axes, lines, data points, bars, wedges—in the same way. Use distinct visual effects only to make distinctions, never just for variety.

■ Use arabic numerals for all numerical data.

■ Label all axes using sentence-style capitalization. Keep the labels short, following practices for good table titles (see 8.3.1). Use the figure caption (see 26.3.2) to explain any aspects of the data that cannot be captured in the labels. To save space, you can use abbreviations and symbols more freely than you can in text, but use them sparingly and consistently. If standard abbreviations do not exist, create your own and explain them either in the caption or, if there are many, in a list of abbreviations in your paper’s front matter (see A.2.1).

■ Label lines, data points, and other items within the chart or graph that require explanation using either all lowercase letters (for single words) or sentence-style capitalization (for phrases). If phrases and single words both appear, they should all be styled the same (as in fig. 8.3). The other principles described above for axis labels also apply to labels of this type.

■ Use caution in employing shading or color to convey meaning (see 8.3.2). Even if you print the paper on a color printer or submit it as a PDF, it may be printed or copied later on a black-and-white machine, and if it is a dissertation, it may be microfilmed. Shading and color may not reproduce well in any of these forms. If you use shading, make sure it does not obscure any text in the figure, and do not use multiple shades, which might not reproduce distinctly.

26.3.2 Figure Numbers and Captions

In general, every figure in your paper should have a number and a caption. If you include only a few figures in your paper and do not specifically refer to them in the text, omit the numbers. Figure captions may be presented in a smaller typeface than the rest of your text; consult your local guidelines.

On the line below the figure, write the word Figure (flush left, capitalized, in roman type), followed by the figure number (in arabic numerals), followed by a period. After a space, give the caption, usually followed by a terminal period (but see 26.3.3.2). If a caption runs onto more than one line, the runovers should be flush left, single-spaced.

Figure 6. The Great Mosque of Cordoba, eighth to tenth century.

In examples from musical scores only, place the figure number and caption above the figure.

26.3.3.1 FIGURE NUMBERS. Number figures separately from tables, in the order in which you mention them in the text. If you have only a few figures, number them consecutively throughout the paper, even across chapters. If you have many figures and many chapters, use double numeration: that is, the chapter number followed by a period followed by the figure number, as in Figure 12.4.

When you refer to a figure in the text, specify the figure number (“in figure 3”) rather than its location (“below”), because you may end up moving the figure while editing or formatting the paper. Do not capitalize the word figure in text references to figures, and do not abbreviate it as fig. except in parenthetical references—for example, “(see fig. 10).”

26.3.3.2 FIGURE CAPTIONS. Figure captions are more varied than table titles. In some cases, captions can consist solely of a noun phrase, capitalized sentence style (see 22.3.1), without a terminal period.

Figure 9. Mary McLeod Bethune, leader of the Black Cabinet

More complex captions begin with a noun phrase followed by one or more complete sentences. Such captions are also capitalized sentence style but have terminal periods, even after the initial incomplete sentence. If your captions include a mix of both types, you may include a terminal period in those of the first type for consistency.

Figure 16. Benito Juárez. Mexico’s great president, a contemporary and friend of Abraham Lincoln, represents the hard-fought triumph of Mexican liberalism at midcentury. Courtesy of Bancroft Library, University of California at Berkeley.

When a figure has a source line, put it at the end of the caption, following the guidelines in 26.1.3.

Figure 2.7. The lao Valley, site of the final battle. Photograph by Anastasia Nowag.

Figure 11.3. US population growth, 1900–1999. Data from US Census Bureau, “Historical National Population Estimates,” accessed August 9, 2011, http://www.census.gov/popest/archives/1990s/popclockest.txt.

Sometimes a caption is attached to a figure consisting of several parts. Identify the parts in the caption with terms such as top, bottom, above, left to right, and clockwise from left (italicized to distinguish them from the caption itself) or with lowercase italic letters.

Figure 6. Above left, William Livingston; right, Henry Brockholst Livingston; below left, John Jay; right, Sarah Livingston Jay.

Figure 15. Four types of Hawaiian fishhooks: a, barbed hook of tortoise shell; b, trolling hook with pearl shell lure and point of human bone; c, octopus lure with cowrie shell, stone sinker, and large bone hook; d, barbed hook of human thigh bone.

If the caption for a figure will not fit on the same page as the figure itself, put it on the nearest preceding text page (see A.3.1.4), with placement identification in italics before the figure number and caption.

Next page: Figure 19. A toddler using a fourth-generation iPhone. Refinements in touchscreen technology helped Apple and other corporations broaden the target market for their products.