Figure 5.1 Intra-EAC Traffic, 2004–13

Source: Analysis based on data from DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Note: Bi-directional traffic capacity. Number after year indicates month, 07 = July. EAC = East African Community.

After having established the key elements of the low-cost carrier (LCC) business model, and identifying the market environment that they can flourish in, chapter 5 provides insight into the potential development of LCCs in Sub-Saharan Africa, a region which still represents largely unexplored territory for the business model. Due to the region’s vastness, complexity, and diversity, this chapter focuses on identifying opportunities and challenges using the example of the East African Community (EAC).

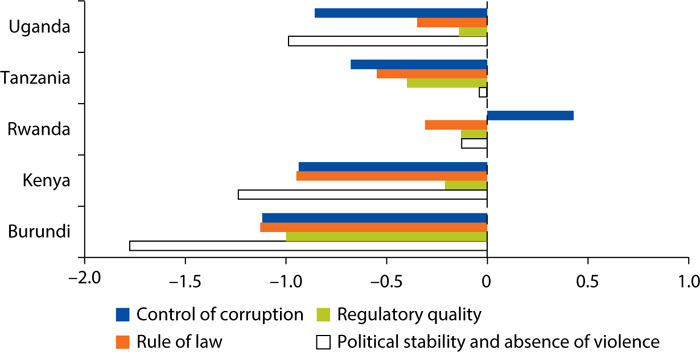

The EAC is a regional economic community (REC) formed between five East African countries: Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi, and Kenya. The region covers around 1.82 million square kilometers, and includes a population of 141.1 million (East African Community Statistics Portal 2013).

The history of the EAC goes back as far as 1917, when Kenya and Uganda formed one of the first cooperative entities in Africa by establishing a customs union. After assuming different shapes and forms—and even a temporary dissolution in 1977—the three major economies of Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda formed the EAC in 2000. In 2007, Rwanda and Burundi joined the EAC. Based on the EAC Treaty of 1999 (EAC 1999), which forms the legal basis of the community, its prime objective is to “develop policies and programs aimed at widening and deepening cooperation among the Partner States in political, economic, social and cultural fields, research and technology, defense, security and legal and judicial affairs, for their mutual benefit” (EAC 1999). To achieve these objectives, the EAC was to establish a customs union, a common market, and subsequently a monetary union, ultimately leading to a political federation (EAC 1999).

The EAC Treaty lays out a set of fundamental and operational principles that must govern the achievement of these objectives. The most significant fundamental principles include “mutual trust, political will, and sovereign equality,” as well as “peaceful coexistence and settlement of disputes” (EAC 1999). The community’s key operational principles are “the establishment of an export oriented economy for the Partner States in which there shall be free movement of goods, persons, labor, services, capital, information and technology” and the “principle of subsidiarity” of the EAC, which secures multilevel participation and the involvement of a wide range of stakeholders during the integration process (EAC 1999).

Air Transportation has been given particular attention in the EAC Treaty under Section 92. As its objective, EAC member countries are to “harmonize their policies on civil aviation to promote the development of safe, reliable, efficient, and economically viable civil aviation with a view to developing appropriate infrastructure, aeronautical skills and technology, as well as the role of aviation in support of other economic activities” (EAC 1999). There are also some specific provisions for different areas of the industry, which are outlined throughout this chapter.

Overall, the institutional framework of the newly established EAC is well defined and consists of all of the necessary elements for effective implementation of its goals, including economic cooperation and integration among its partner states.

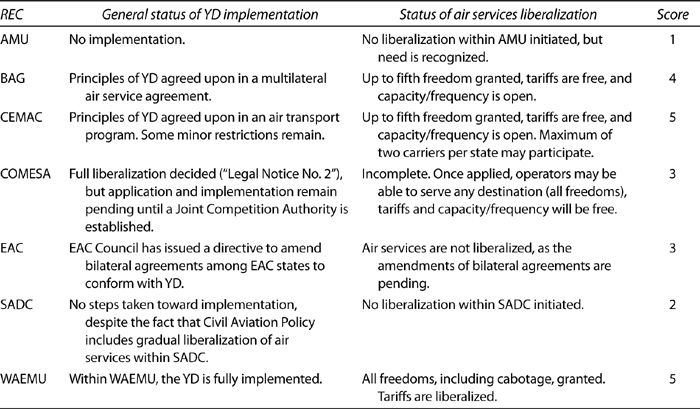

In addition to the EAC, some of its member states are also part of other RECs. These may have different policies with regard to the air transport sector. Burundi, Rwanda, Kenya, and Uganda, for example, are also part of the Common Market for Eastern and Southern Africa (COMESA), a regional organization that has established a free trade zone between eastern, southern, and central African states.1 Tanzania is also a part of the Southern African Development Community (SADC). SADC’s objective is socioeconomic cooperation and integration, as well as political and security cooperation. It includes 15 members from the southern African region.

These dual/multiple regional bloc memberships of EAC states have, in some cases, slowed down decision-making processes due to the need for harmonization between individual RECs. To address this obstacle, EAC, COMESA, and SADC founded the COMESA-EAC-SADC Tripartite in 2005. The Tripartite decided to develop a road map for the harmonization of the three RECs at the Tripartite Summit of Heads of State in 2008. However, this has not been achieved yet. It has also been working toward the implementation of a comprehensive Trade and Transport Facilitation Programme, including providing support for various aspects of the air transport sectors (OECD and WTO 2011).

As established in chapter 4, the key factor for LCCs to flourish in a market is high utilization of their aircraft and personnel. This in turn requires high expected volumes of traffic. These volumes can be achieved by either targeting existing customers on high traffic routes to reduce market share of incumbent carriers, by stimulating new demand by attracting a larger segment of the population through a lower fare offering, or by opening previously unserved routes. In order to assess the opportunities in the EAC market, a short overview of the existing market, as well as an analysis of the potential for future growth opportunities, are provided below. This is by no means an exhaustive assessment, but serves as an overall indicator of trends in the market. A more detailed analysis would be required to assess actual route-level opportunities, and is beyond the scope of this research.

In order to provide a broad overview of the air transport market, this book primarily focuses on current air traffic capacity, as well as on the key participants in the market. Although some passenger data is available from the EAC Secretariat for an analysis of the existing EAC market, it is difficult to verify the data’s accuracy. Therefore, this analysis relies on information from airline schedules as collated through the online database DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013), and a sample of passenger flow data for some African airports as provided by the Airports Council International. Using schedules data has the disadvantage that only capacity is provided rather than actual passengers flown. However, it does serve as an indication of overall traffic flows.

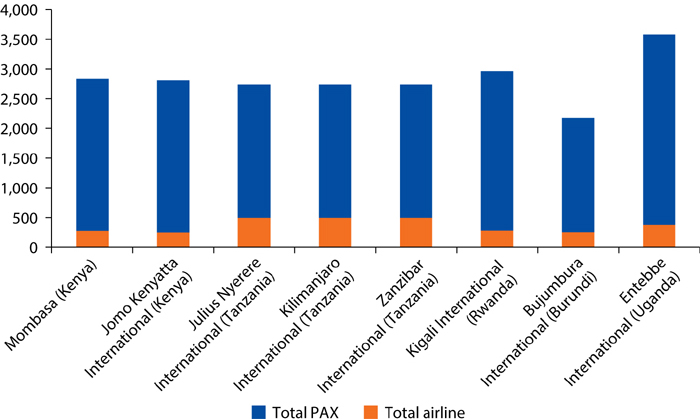

The current intra-EAC air transport market is still very small and the majority of domestic and regional traffic is still concentrated around the two major hubs of Nairobi, Kenya, and Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. These two airports absorb the largest number of passengers followed by Mombasa, Kenya, and Entebbe, Uganda (see table 5.1).

Table 5.1 Passengers by Airport, 2012

Airport |

IATA |

PAX |

Jomo Kenyatta International Airport, Nairobi, Kenya |

NBO |

6,271,922 |

Julius Nyerere International Airport, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania |

DAR |

2,088,282 |

Moi International Airport, Mombasa, Kenya |

MBA |

1,347,908 |

Entebbe International Airport, Entebbe, Uganda |

EBB |

1,342,134 |

Abeid Amani Karume International Airport, Zanzibar, Tanzania |

ZNZ |

787,813 |

Kilimanjaro International Airport, Kilimanjaro, Tanzania |

JRO |

665,147 |

Kigali International Airport, Kigali, Rwanda |

KGL |

458,807 |

Mwanza Airport, Mwanza Tanzania |

MWZ |

392,298 |

Aéroport International De Bujumbura, Bujumbura, Burundi |

BJM |

291,838 |

Eldoret Airport, Eldoret, Kenya |

EDL |

103,729 |

Source: ACI 2012.

Note: IATA = International Air Transport Association; PAX = number of passengers.

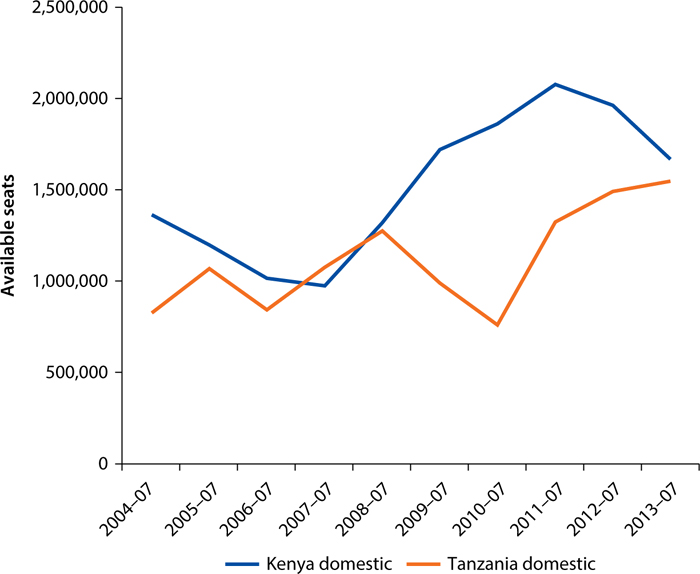

As figure 5.1 shows, despite growth in recent years, the capacity for total traffic between the EAC member countries is still at less than 2.6 million available seats in 2013. This represents around 44 percent of total traffic within the region, highlighting the key role of domestic traffic, particularly in larger countries such as Kenya and Tanzania.

Figure 5.1 Intra-EAC Traffic, 2004–13

Source: Analysis based on data from DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Note: Bi-directional traffic capacity. Number after year indicates month, 07 = July. EAC = East African Community.

Some domestic markets have grown considerably in recent years, especially in Rwanda and Tanzania. After a period of decline between 2008 and 2010, Tanzania in particular has managed to increase its capacity significantly, reaching almost the same level of domestic traffic as Kenya, the largest domestic market in EAC (see figure 5.2).

Figure 5.2 Domestic Traffic Kenya and Tanzania, 2004–13

Source: Based on data from DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Note: Bi-directional traffic capacity. Number after year indicates month, 07 = July.

Rwanda experienced a spike in domestic air transport starting in 2010 (see figure 5.3), with the country’s national airline Rwandair increasing its weekly frequency between Kigali and Cyangugu sixfold between 2010 and 2013. After a short period of increased traffic, Uganda’s domestic market has been declining considerably (see figure 5.3), with many of the domestic, probably largely unprofitable, routes being abandoned by 2010. Burundi currently has no scheduled domestic air transport.

Figure 5.3 Domestic Traffic Uganda and Rwanda, 2004–13

Source: Analysis based on data from DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Note: Bi-directional traffic capacity. Number after year indicates month, 07 = July.

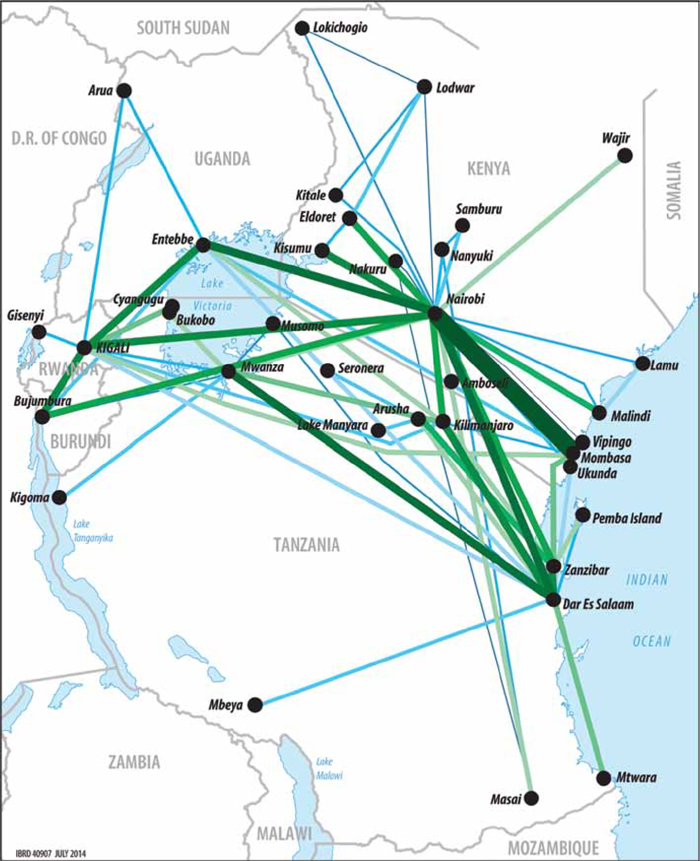

As map 5.1 shows, the majority of traffic in East Africa can be broadly divided into three main categories: (a) a few high-frequency domestic routes in Tanzania and Kenya; (b) a small number of key intra-EAC routes with low frequency; and (c) a number of secondary, low-capacity intra-EAC routes. The top 15 routes amount to around 80 percent of the overall EAC market.

Map 5.1 Route Network Map of EAC

Source: Based on data from DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Note: Thickness of a route indicates the level of traffic intensity (thick = high, thin = low). EAC = East African Community.

A few high frequency domestic routes represent a large share of overall traffic in the EAC. These are located primarily in Tanzania and Kenya, connecting their respective entry hubs in Dar es Salaam (DAR) and Nairobi (NBO) to their main economic and tourism centers. In Kenya, direct domestic traffic primarily links Nairobi (NBO) and Mombasa (MBA), Kenya’s two largest cities and economic centers. There are 15–17 roundtrip daily flights connecting the two cities. High frequency domestic traffic also occurs between Dar es Salaam (DAR) and Mwanza (MZW), Kilimanjaro (JRO) and Zanzibar (ZNZ). This feeds tourism traffic from the country’s capital airport to popular tourist destinations.

International intra-EAC traffic is limited to a few key routes, primarily linking the EAC’s large- and medium-size cities to the region’s hub in Nairobi. In addition, key routes include services between capital cities such as Entebbe (EBB) and Kigali (KGL), and Kigali (KGL) and Bujumbura (BJM), as well as popular tourist destinations such as the route from Zanzibar to Mombasa. Together, the top 15 intra-EAC routes comprise almost 90 percent of all international intra-EAC traffic in 2013.

Some of these routes have grown consistently in recent years, such as the Nairobi (NBO) to Kigali (KGL), or the Entebbe (EBB) to Kigali (KGL) route. Others have undergone significant fluctuations, including the Nairobi (NBO) to Entebbe (EBB) route, or the Dar es Salaam (DAR) to Nairobi (NBO) route. The former experienced a considerable drop in capacity in 2005 and 2006, after Ethiopian Airlines suspended its flights on the routes in 2005. Trying to resume the flights in 2006, the Kenyan government refused to grant traffic rights to the carrier (New Vision 2006). This left Kenya Airways as the sole provider on the route for some time.

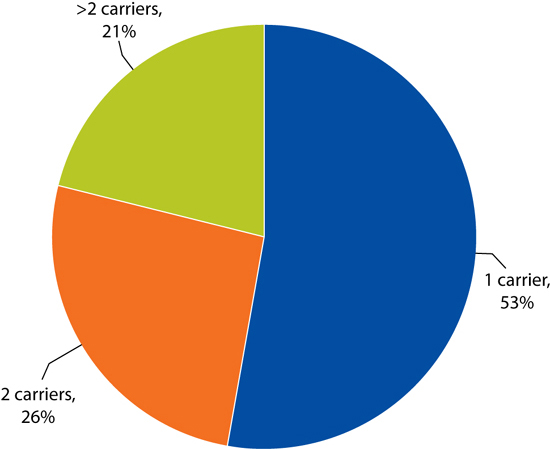

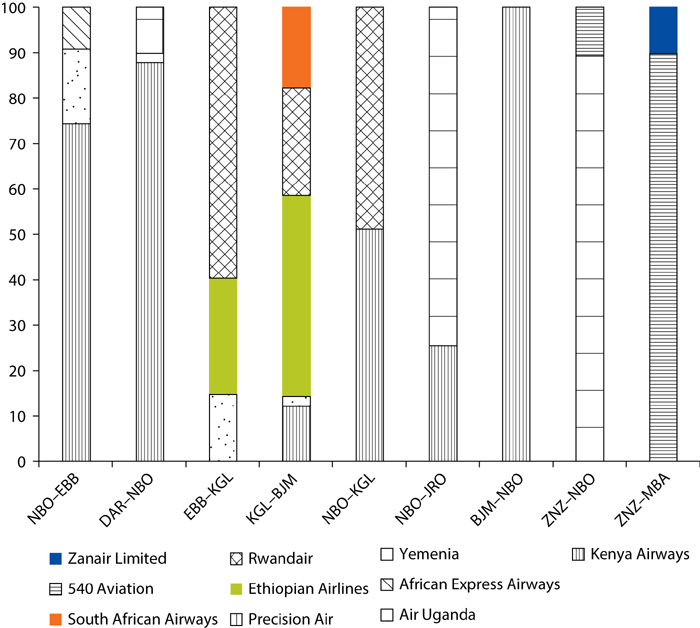

Intra-EAC traffic is dominated by few carriers and competition is very limited. As figure 5.4 shows, most intra-EAC routes are operated by one or two carriers. Even on routes where more than two carriers operate, such as the Nairobi (NBO) to Entebbe (EBB) route or the Nairobi (NBO) to Dar es Salaam (DAR) route, these routes are mostly dominated by one carrier (figure 5.5). However, a few routes from Kigali have been served by multiple carriers, with Ethiopian Airlines and South African Airways applying their fifth freedom rights.

Figure 5.4 Number of Carriers per Top Intra-EAC Routes, July 2013

percent

Source: Analysis based on data from DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Figure 5.5 Market Share per Carrier on Top Intra-EAC Routes, July 2013

available seats (%)

Source: Analysis based on data from DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Note: BJM = Bujumbura International Airport, Burundi; DAR = Julius Nyerere International Airport (Dar es Salaam), Tanzania; EAC = East African Community; EBB = Entebbe International Airport, Uganda; JRO = Kilimanjaro International Airport, Tanzania; KGL = Kigali International Airport, Rwanda; MBA = Moi International Airport (Mombasa), Kenya; NBO = Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (Nairobi), Kenya; ZNZ = Abeid Amani Karume International Airport (Zanzibar), Tanzania.

In domestic markets, Tanzania appears to have the least concentration on its routes, with a handful of segments served by more than one carrier. In Kenya’s large domestic market, many routes are still served only by Kenya Airways, although some key routes have seen the entry of competitors—driven by the country’s move toward a deregulated domestic market. The entrance of the LCC Fly540 (discussed later), for example, has brought some competition to the more prominent domestic routes previously only served by Kenya Airways. Prior to the airline’s entry, the domestic market appears to have been clearly divided between the more prominent domestic routes (for example, Nairobi to Mombasa or Eldoret) served by Kenya Airways, and the thinner routes by local carrier Air Kenya Express. This division occurred in recent years with the exit of domestic carriers, such as JetLink Express (which ceased operations in 2012) and African Express Airways from some these routes. In Rwanda and Uganda, the small domestic markets are monopolized by one carrier, Rwandair and Eagle Air. Considering the low traffic volumes in these markets though, the ability of another airline to operate profitably is in some cases questionable.

In addition, there are a number of domestic and some international so-called “milk-runs,” or multistop routes, such as Nairobi (NBO) to Kisumu (KIS) to Eldoret (EDL) to Nairobi (NBO); and Nairobi Wilson Airport (WIL) to Samburu (UAS) to Nanyuki (NYK) to Masai Mara (MRE) in Kenya; or Kilimanjaro (JRO) to Zanzibar (ZNZ) to Dar es Salaam (DAR) in Tanzania. These all show very limited traffic however.

Although still struggling with some unprofitable state-owned carriers such as Rwandair (Butera 2013) and Air Burundi—and in contrast to other regions in Sub-Saharan Africa—the market in the EAC has developed a few privately owned carriers. This includes, for example, Air Uganda which was created after the liquidation of the failing national carrier Uganda Airlines. The airline is part of the Celestair Group of African carriers, which is owned by the Aga Khan Fund for Economic Development (AKFED). Another private airline is Precision Air, the growing Tanzanian carrier, which posted a profit of around US$400,000 in 2012. However, in 2013, the airline had to report losses of US$18.9 million apparently due to “overly ambitious growth.” The carrier expanded its network considerably in that year and leased three B737–800 aircraft (CAPA 2013a). The region has also witnessed the successful privatization of Kenya’s national carrier Kenya Airways in 1995, the largest carrier in the region. In addition, there are a handful of smaller domestic scheduled and charter operators primarily in Kenya and Tanzania, such as Air Kenya Express, Regional Air, and Zanzair. A detailed list of the major carriers in the region can be found in appendix E.

Despite the positive progress in privatization, government intervention in the air transport sector may not have disappeared entirely. Kenya Airways’ financial difficulties led to a recent news announcement stating that the government of Kenya is considering increasing its share in the carrier (Muiri 2013). This may serve as an indicator for a potentially more active involvement of the government in the air transport market. A small sign of intervention was already evident with the denial of traffic rights for Ethiopian Airlines in 2006, which left Kenya Airways as the only provider on the Entebbe (EBB) to Nairobi (NBO) route. The Ugandan government also announced recently that it was planning to re-launch its national carrier Air Uganda. The airline went into bankruptcy in 2001 after unsuccessfully trying to attract foreign investors (CAPA 2013b). Even the government of Tanzania is considering an equity stake in Precision Air (CAPA 2013a).

Due to limited traffic in the region, most airlines use smaller turboprop aircraft (for example, ATR-42 and 72, DHC-8), some regional jets (for example, CRJ Bombardier), as well as a very limited number of narrow-body jets (for example, B737, A320, Embraer E-Jet) for intra-regional routes. In addition, there are a number of small domestic and regional airlines such as Zanair operating with smaller piston engine aircraft (for example, Cessna 402).

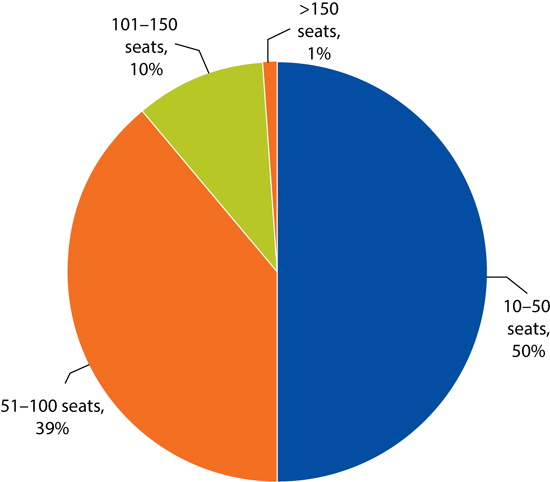

As figure 5.6 shows the frequent usage of aircraft with capacities below 100 seats is fairly common in the region. As a recent analysis by Bombardier shows, there has been a shift in the usage of aircraft in Africa to 75–100-seat aircraft, which more than doubled between 2007 and 2012 (Carrier 2013).

Figure 5.6 Number of Flights per Aircraft Size, July 2013 (Intra-Regional and Domestic)

percent

Source: Analysis based on data from DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Even with smaller aircraft, airlines operating in Africa generally experienced lower load factors. A study by the International Air Transport Association (IATA) showed that in 2013, load factors were around 10 percent lower than in most other regions (IATA 2013). This signals that the usage of larger aircraft would most likely not be sustainable. The viability of regional jets for the LCC model is still questionable, however, due to generally higher unit costs (per available seat kilometer or mile: CASK or CASM) in comparison to the commonly used A320 and B737 narrow-body jets.

The region has already seen the emergence of its first low-cost airlines. In 2006, Fly540, a Kenya-based, low-cost airline was established. The carrier, owned by Five Forty Aviation Ltd., with a 49 percent investment stake by British company Lonrho Africa, introduced the first LCC model to the region. Based on its name, Fly540 offered a no-frills air transport service for 5,540 Kenya shillings (K Sh; approximately US$60) roundtrip fare. Starting with the high traffic Nairobi (NBO) to Mombasa (MBA) route with a 48-seat ATR42 aircraft, the airline expanded quickly adding new aircraft (two Dash 8–100s), and extending its route network to include Kisumu, Eldoret, Malindi, Lodwar, and Lamu in Kenya. Later it also targeted international destinations in the Republic of South Sudan, Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Uganda by acquiring the Kenyan carrier East African Safari Air Express in 2010 (Thome 2010). Some of these expansion plans were later abandoned, however, primarily due to political and financial reasons (CAPA 2012). The company also set up its first franchise in Tanzania based at Mwanza Airport, operating flights to Zanzibar, Dar es Salaam, and Nairobi (CAPA 2012).

Building on its success in East Africa, Fly540 set up operations in Angola and Ghana in 2011. In Angola, Fly540 focuses on domestic operations between the country’s capital Luanda and smaller cities, such as Soyo, Benguela, Cabinda, and M’banza Congo (Fly540 Africa 2013). The Angola operation commenced with a significant delay as the country had been under scrutiny by the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) and the country’s primary carrier had been blacklisted by the European Union due to safety concerns (CAPA 2011). In Ghana, services were initially operated to Tamale, Kumasi, and Takoradi domestically, and Abidjan and Freetown internationally. However, these services were discontinued, and according to the airline’s website, the only operation remaining is between Accra and Kumasi, a wealthy mining city northwest of Accra. Although intending to become a regional hub, plans to develop services to Senegal and Equatorial Guinea were not realized. The airline also voiced ambitions to set up franchises in Rwanda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe, among other countries. By the end of 2011, the carrier recorded passenger figures of almost half a million (easyGroup 2013) across its operations with a fleet of 10 aircraft by June 2012 (CAPA 2012). In contrast, by its fourth year of operation in 2000, easyJet in Europe had recorded 5.6 million passengers (CNN 2000) with a fleet of 14 B737 aircraft (Planespotters 2013).

Despite this aggressive expansion strategy and increasing passenger growth, Lonrho Aviation’s operations did not yield the desired results. In September 2009, it reported a loss (after tax) of US$7.5 million for the previous 12 months. This loss increased even further in September 2010 and 2011 to US$13.1 million and US$19.0 million, respectively. The 12 months ending September 30, 2009, showed a 24 percent negative operating margin, which increased to 35 percent the following year (September 2010), and then slightly decreased to 31 percent for the 15 months to December 31, 2011 (CAPA 2012). The airline’s losses were primarily attributed to the establishment of its new franchises in Angola and Ghana, as well as unprofitable operations in Uganda. In addition, the carrier had been struggling with fuel-inefficient, small aircraft and insufficient utilization rates.

In 2012, Rubicon Ltd., a British investment company, purchased Lonrho’s aviation arm and its investments in Fly540. The payment to Lonrho consisted of Rubicon shares for a total value of US$85.7 million, representing 73.7 percent of Rubicon’s enlarged issued share capital. Another 5 percent of shares are owned by Sir Stelios Haji-Ioannou of easyGroup Holding Limited, the parent company of European LCC easyJet. Under a brand licensing agreement with easyGroup, the airline rebranded itself into fastjet (Lonrho Aviation 2012).

Fastjet has announced its transformation into a “real” low-cost airline, replacing the carrier’s turboprop aircraft with Airbus 319s. In addition, it engaged in alternative distribution channels such as mobile distribution channels to avoid the expensive costs of global distribution system (GDS) providers. The airline was planning to increase its fleet to 15 A319 aircraft by the end of 2013 (CAPA 2013c). Its service offering is not entirely clear, but appears to be influenced by the LCC model of easyJet—attracting business and leisure travelers by offering food and beverages, priority boarding, and seating at a charge—and most importantly, providing connections to intercontinental carriers (CAPA 2012).

Focusing firstly on the East African market, the airline has encountered numerous challenges. It has an ongoing legal dispute with Five Forty Aviation, the previous owner of the Kenya Fly540 brand (and, although debated, still its majority shareholder) about operations into and within Kenya, as well as delays in obtaining international flying rights from Tanzania into other markets in the region. The airline has therefore been able to take over only Fly540’s domestic operations in Tanzania. The delay in commencing operations in Kenya is particularly challenging as the launch of Kenya Airways’ long-awaited LCC Jambo Jet seems to be coming closer. Trying to free up some much needed funds to recoup the cost incurred from these delays, the company has announced that it intends to reduce its 90 percent equity shareholding in Fly540 Tanzania (Peterson 2013).

While trying to salvage its position in East Africa, Fly540’s West African operations in Angola and Ghana (in which fastjet owns 60 percent and 92.5 percent of shares respectively) have also significantly underperformed in 2012. Fly540 Angola has been struggling with bureaucratic hurdles, such as stringent regulations on transactions imposed by the Angolan Central Bank, and customs delays affecting the delivery of aircraft spares. Fly540 Ghana has faced intense competition on its Accra (ACC) to Kumasi (KMS) route with the entrance of two new LCCs, Starbox and Africa World Airlines. The carrier’s cost structure has also been severely affected by excessive passenger taxes, airport services charges, and fuel price increases (CAPA 2013d).

As a result, fastjet posted a loss of US$56 million for the 18 months leading up to December 31, 2012. The auditors, KPMG, voiced concerns about the company’s stocks’ ability to continue to be traded on the London Stock Exchange. Losses in West Africa have been particularly detrimental, amounting to US$17.8 million (CAPA 2013d).

However, since the beginning of 2013, the company has demonstrated success in the Tanzanian market, with high average load factors on the routes between Dar es Salaam (DAR) and Kilimanjaro (JRO), and Dar es Salaam (DAR) and Mwanza (MWZ), where 38 percent of passengers were first-time flyers. Recently, Fly540 Ghana has also experienced increased bookings. In May 2013, it recorded an 11 percent increase from April 2013 and 52 percent from May 2012. Web-based sales in the country have experienced a large increase of nearly 400 percent, reducing the company’s distribution costs. In addition, the airline has managed to finalize a license-based joint venture with a South African investment company, Blockbuster, to enter the South African domestic market. This finally succeeded after a variety of attempts to enter the market, including the proposed purchase of bankrupt South African carrier 1Time (CAPA 2013d). Despite this promising outlook, the overall viability of the carrier still remains to be seen.

In order to provide an assessment of fare levels in the EAC market, two comparisons are made; one for domestic and one for intra-EAC routes, with routes in other regions that are currently operated by LCCs (see appendix F for detailed methodology and sample airports chosen).

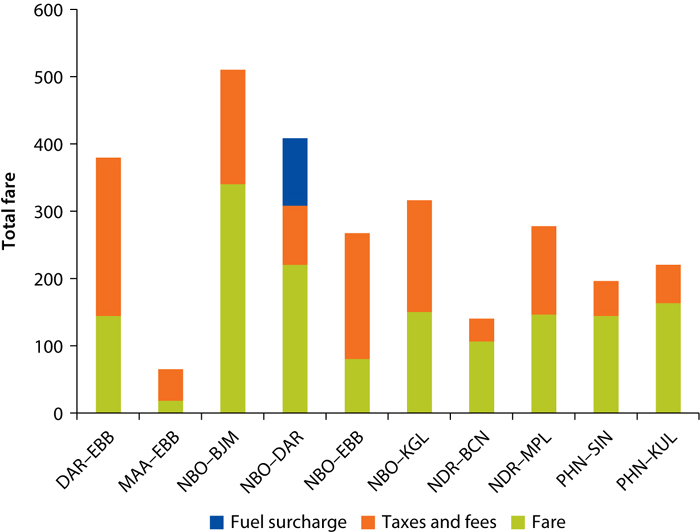

As figure 5.7 shows, the lowest available return fares on comparable routes are significantly lower than on intra-EAC routes. Particularly routes originating from Morocco and Cambodia prove to be significantly lower. The route between Nairobi (NBO) and Dar es Salaam (DAR), for example, is over 100 percent more expensive than the route between Kuala Lumpur (KUL) and Phnom Penh (PNH). The fare from Nairobi (NBO) to Zanzibar (ZNZ) is almost three times higher than from Chennai (MAA) to Colombo (CMB).

Figure 5.7 Comparison of Lowest Available Return Fare between Intra-EAC and Other International Routes (Including Taxes and Charges)

Sources: Analysis based on airline websites, Air Uganda, Jet Airways, Kenya Airways, Precision Air, Rwandair, Ryanair, AirArabia Maroc, Jetstar Asia, Air Asia, and Fly540; and DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

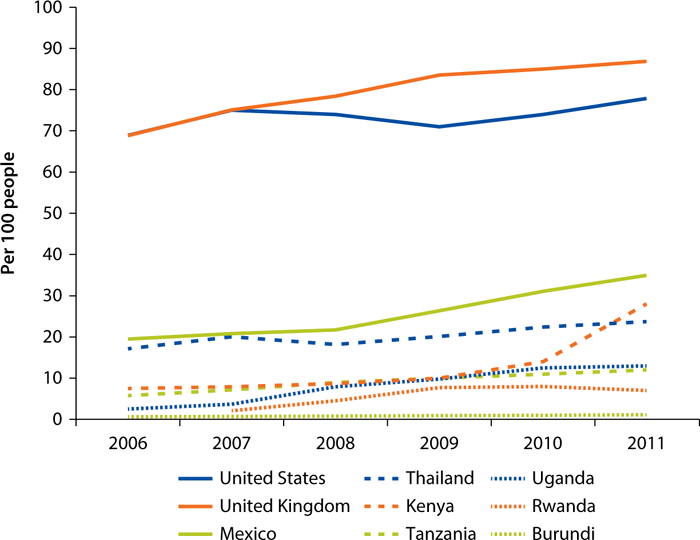

Note: BCN = Barcelona el Prat Airport, Spain; BJM = Bujumbura International Airport, Burundi; CMB = Bandaranaike International Airport (Colombo) Sri Lanka; DAR = Julius Nyerere International Airport (Dar es Salaam), Tanzania; EAC = East African Community; EBB = Entebbe International Airport, Uganda; KGL = Kigali International Airport, Rwanda; KUL = Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Malaysia; MAA = Chennai International Airport, India; MPL = Montpellier Méditerranée Airport, France; NBO = Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (Nairobi), Kenya; NDR = Nador International Airport, Morocco; PNH = Phnom Pen International Airport, Cambodia; SIN = Singapore Changi Airport; ZNZ = Abeid Amani Karume International Airport (Zanzibar), Tanzania.

In looking at the distribution of cost versus taxation and charges, it is clear that taxation and charges comprise a large percentage of total fares on intra-EAC markets (see figure 5.8). There are also some cases where the base fare is much higher, such as on the Nairobi (NBO) to Bujumbura (BJM) route, which could be directly linked to the limited competition on this segment.

Figure 5.8 Distribution Fare Basis versus Taxation and Charges, 2013

US$

Sources: Analysis based on airline websites including Air Uganda, Jet Airways, Kenya Airways, Precision Air, Rwandair, Ryanair, AirArabia Maroc, Jetstar Asia, Air Asia, and Fly540; and DiiO Analyzer (2013).

Note: ZNZ-NBO had to be excluded as website did not provide for a breakdown of the fare. BCN = Barcelona el Prat Airport, Spain; BJM = Bujumbura International Airport, Burundi; CMB = Bandaranaike International Airport (Colombo) Sri Lanka; DAR = Julius Nyerere International Airport (Dar es Salaam), Tanzania; EBB = Entebbe International Airport, Uganda; KGL = Kigali International Airport, Rwanda; KUL = Kuala Lumpur International Airport, Malaysia; MAA = Chennai International Airport, India; MPL = Montpellier Méditerranée Airport, France; NBO = Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (Nairobi), Kenya; NDR = Nador International Airport, Morocco; PNH = Phnom Pen International Airport, Cambodia; SIN = Singapore Changi Airport; ZNZ = Abeid Amani Karume International Airport (Zanzibar), Tanzania.

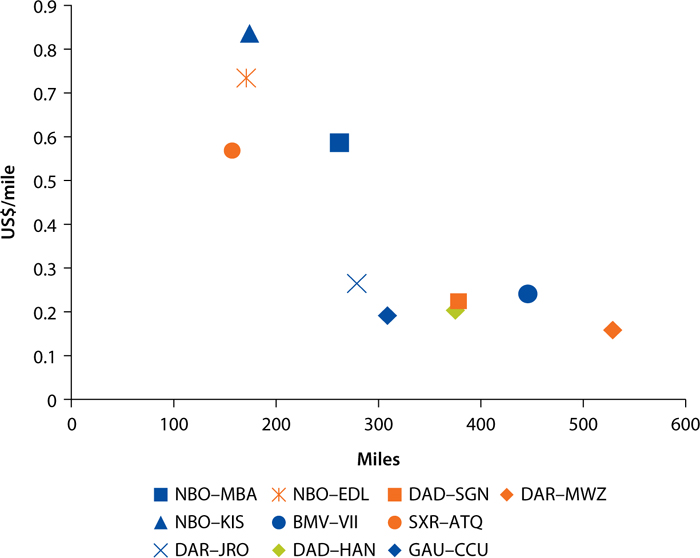

As figure 5.9 shows, fares on domestic routes in Kenya are generally more expensive than the routes in the chosen sample. Interestingly, on the routes where LCC Fly540 is present in Kenya, Kenya Airways actually undercuts the LCC by a small margin on the chosen dates, thereby displaying some sign of fare convergence in the market. The competition with the LCCs seems to have brought down fares to a similar level than on comparable sectors for some routes, such as the Nairobi (NBO) to Mombasa (MBA) route, but not on others such as the Nairobi (NBO) to Eldoret (EDL) and the Nairobi (NBO) to Kisumu (KIS) routes.

Figure 5.9 Comparison of Lowest Available Domestic Fare (Including Taxes and Charges)

Sources: Analysis based on airline websites including Kenya Airways, Precision Air, Fastjet, Jetstar Pacific, and Spicejet; and DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Note: ATQ = Sri Guru Ram Dass Jee International (Amritsar), India; BMV = Buon Ma Thuot Airport, Vietnam; CCU = Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose International Airport (Kolkata), India; DAD = Da Nang International Airport, Vietnam; DAR = Julius Nyerere International Airport (Dar es Salaam), Tanzania; EDL = Eldoret International Airport, Kenya; GAU = Guwahati Airport, India; HAN = Noi Bai International Airport (Hanoi), Vietnam; JRO = Kilimanjaro International Airport, Tanzania; KIS = Kisumu International Airport, Kenya; MBA = Moi International Airport (Mombasa), Kenya; MWZ = Mwanza Airport (Mwanza) Tanzania; NBO = Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (Nairobi), Kenya; SGN = Tân So’n Nhât International Airport (Ho Chi Minh City), Vietnam; SXR = Srinagar International Airport, India; VII = Vinh Airport, Vietnam.

In Tanzania, the entrance of LCC fastjet appears to have lowered fares considerably on par with similar routes in India and Vietnam. One reason for the lower fares offered by fastjet is its removal of the added fuel surcharge of US$80 that its competitor, Precision Air, adds to the ticket price. The exception appears to be the Dar es Salaam (DAR) to Zanzibar (ZNZ) route (not depicted in figure 5.9), which has very high fares per mile. Some of the difference in fare may likely be a result of the enlarged distance on some routes, particularly for the Buon Ma Thuot (BMV) to Vinh City (VII) route in Vietnam.

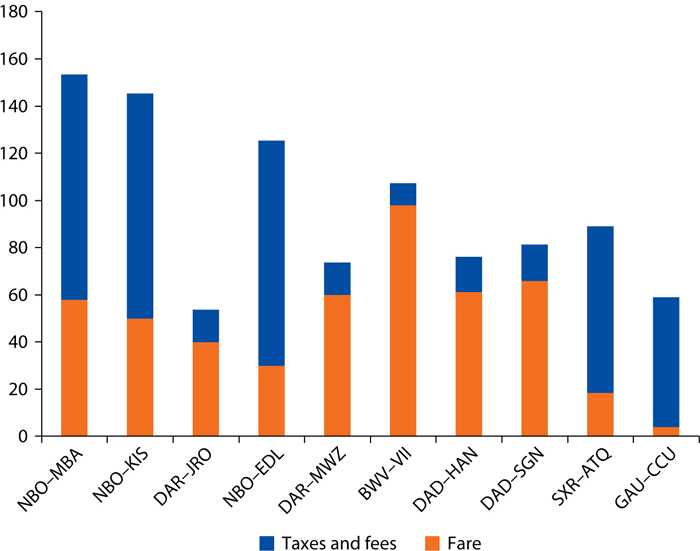

When comparing the distribution of costs between the actual fare and taxes (see figure 5.10), an interesting result can be seen. With the exception of the two routes chosen in the Indian domestic market, base fares in Vietnam are at similar levels or even higher than fares in Kenya and Tanzania. As with international routes, taxation and fees are the key drivers of higher fares.

Figure 5.10 Distribution Fare Basis versus Taxation and Charges

US$

Sources: Analysis based on airline websites, including Kenya Airways, Precision Air, Fastjet, Jetstar Pacific, and Spicejet; and DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013).

Note: ATQ = Sri Guru Ram Dass Jee International (Amritsar), India; BMV = Buon Ma Thuot Airport, Vietnam; CCU = Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose International Airport (Kolkata), India; DAD = Da Nang International Airport, Vietnam; DAR = Julius Nyerere International Airport (Dar es Salaam), Tanzania; EDL = Eldoret International Airport, Kenya; GAU = Guwahati Airport, India; HAN = Noi Bai International Airport (Hanoi), Vietnam; JRO = Kilimanjaro International Airport, Tanzania; KIS = Kisumu International Airport, Kenya; MBA = Moi International Airport (Mombasa), Kenya; MWZ = Mwanza Airport (Mwanza) Tanzania; NBO = Jomo Kenyatta International Airport (Nairobi), Kenya; SGN = Tân Son Nhâ´t International Airport (Ho Chi Minh City), Vietnam; SXR = Srinagar International Airport, India; VII = Vinh Airport, Vietnam.

The identification of potential comparable routes revealed that LCCs in countries in Asia with similar gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and population (allowing for a considerable margin) are almost always connected to a large economic hub such as Singapore or Kuala Lumpur internationally. These not only provide the high feed into those routes, but also have a significantly larger GDP per capita. No examples could be found where countries with similar GDP per capita to EAC countries have LCC services between them at such distances and population numbers. A more extensive analysis over a specific time period would need to be done to validate these results.

As noted, the EAC air transport market is still at its early development stages with few routes of significant traffic and a high concentration of carriers, which include state-owned and, in some cases, possibly “government favored” airlines. The industry has, however, seen a new breed of private carriers such as Precision Air and Air Uganda, as well as the development of an LCC. Despite current limited traffic, leading aircraft manufacturers project significant growth in Africa’s air transport market. Airbus has forecast average annual growth rates for traffic to and within Africa to reach 5.7 percent between 2012 and 2031, well above the global growth of 4.7 percent. Between 2012 and 2031, domestic and intra-regional traffic, of crucial importance for LCCs, is expected to grow at 6.2 percent per year (Airbus 2013).

In order to assess the opportunities for growth in air travel demand, this section elaborates on some of the factors that could influence potential underlying demand, and which could provide the basis for increased air transportation, in particular LCC development in the EAC region.

Spurred by overall political and macroeconomic stability as well as pro-market reforms, the countries of the EAC have seen considerable economic growth in the last decade.

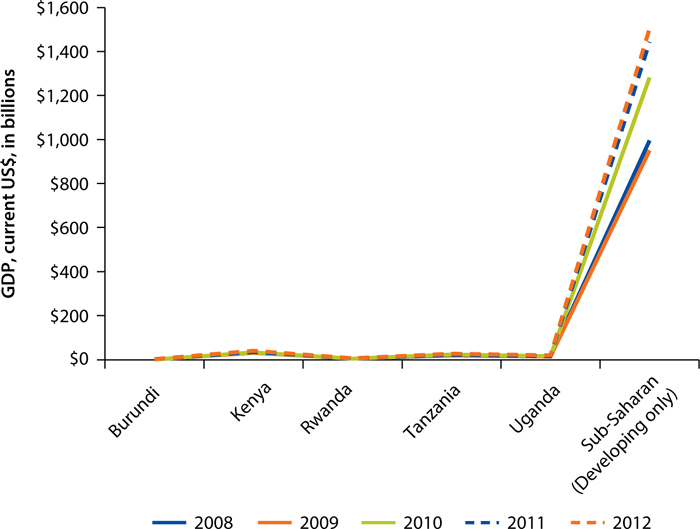

As figure 5.11 shows, all EAC countries have experienced positive GDP growth rates since 2008, in particular Rwanda, Uganda, and Tanzania with average growth rates between 6.4 percent and 8.2 percent. Burundi, plagued by years of civil conflict, has experienced a more stagnant level of growth and Kenya, the largest economy in the region, has showed fluctuating growth levels, with particularly low levels of growth in 2008/2009. The fluctuations were caused by its exposure to the global financial crisis, including reduced flows of remittances and the depreciation of the shilling (McKormick 2008). Overall, GDP growth for most EAC countries appears to be in line or above the average GDP growth rate of 4.1 percent experienced across Sub-Saharan developing countries.

Figure 5.11 GDP Growth in EAC Countries, 2008–12

Source: World Bank 2013c.

Note: EAC = East African Community.

With strong GDP growth, per capita incomes have also been increasing steadily. According to the International Monetary Fund, average per capita income (weighed by population in year 2000 dollars) in EAC had reached US$411 in 2010, close to the US$425 average for Sub-Saharan Africa (excluding South Africa and Nigeria). However, wide variations remain within the region with Kenya displaying an average per capita income of US$464 in comparison to US$147 in Burundi (McAuliffe, Saxena, and Zabara 2012).

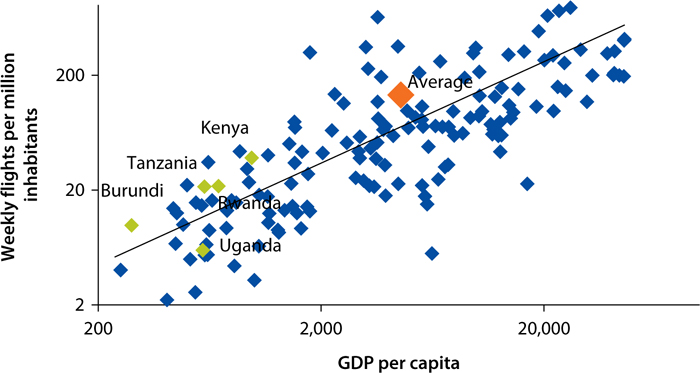

Figure 5.12 shows air transport intensity (domestic and international) in relation to GDP per capita. As indicated, EAC countries, when compared with countries with similar GDP per capita, display a comparable or higher number of weekly flights per million inhabitants. The exception is Uganda, which has a significantly lower number of weekly flights per million inhabitants. This indicates that, all other things being equal, the air transport market in Uganda still has room for growth at current income levels.

Figure 5.12 Flight Intensity in EAC Countries, 2012

Sources: Analysis based on DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013) and World Bank (2013c).

Note: EAC = East African Community.

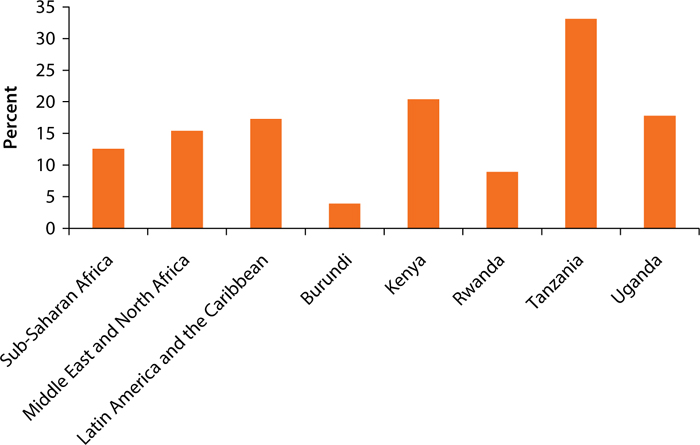

Despite good GDP per capita growth across the region, the emergence of a strong and large middle class has been slow. Poverty levels are still very high in the region, in particular in Burundi where over 90 percent of the population lives below US$2 (purchasing power parity [PPP])2 a day (see figure 5.13). Similar figures can be seen for Rwanda and Tanzania. This puts air transport, even at a lower fare, out of reach for the majority of the population. Indicators measuring inequality, such as the GINI index, are a direct reflection of this (figure 5.14). The Gini coefficient (in figure 5.14, shown as the GINI index) is the most commonly used measure of inequality. The coefficient varies between zero, which reflects complete equality, and one, which indicates complete inequality (that is, one person has all the income or consumption, all others have none). As figure 5.14 highlights, GINI coefficients for Rwanda, Kenya, and Uganda are particularly high.

Figure 5.13 Poverty Headcount Ratio at $2 (PPP)

percent

Source: World Bank 2013c.

Note: PPP = purchasing power parity.

Figure 5.14 GINI Index for EAC

percent

Source: World Bank 2013c.

Note: EAC = East African Community.

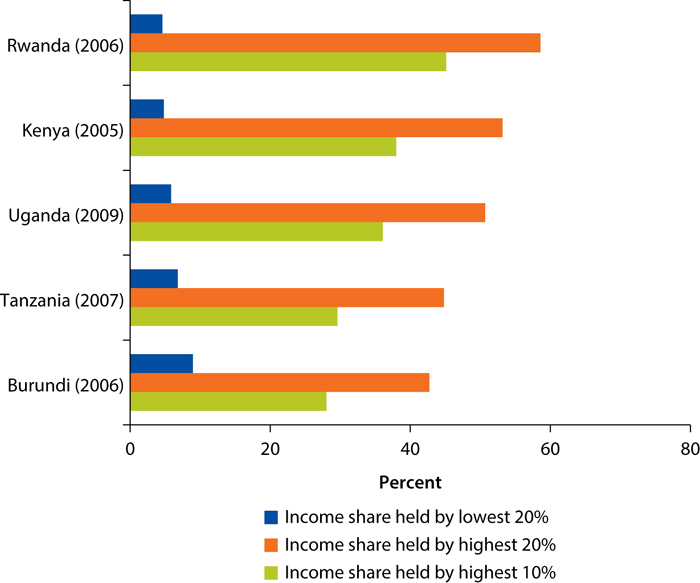

Another measure indicative of the levels of inequality is income share distribution (see figure 5.15). In contrast to the GINI coefficient, this gives a clearer picture of where shifts are occurring within the different income classes over time. Due to the lack of data for EAC countries, however, figure 5.15 is only able to display a snapshot of the most recent data. Still, it clearly indicates a strong unequal distribution of wealth in EAC countries. In Rwanda, Kenya, and Uganda, for example, the top 20 percent of the population holds over 50 percent of the country’s income. In Uganda, where two data points are available, this inequality appears to be increasing further since 2006.

Figure 5.15 Wealth Distribution in EAC Countries

Source: World Bank 2013c.

Note: EAC = East African Community.

According to an analysis of the region undertaken by the International Monetary Fund (IMF), in order to achieve significant poverty reduction and middle-income status, the region’s real GDP per capita will have to grow at an average rate of 5.5 percent until the end of this decade. This is around two percentage points faster than between 2005 and 2010. Kenya is probably closest to achieving middle-income status, whereas Uganda, Tanzania, and Rwanda would have to grow their per capita income by 7–8 percent a year. For Burundi, this is expected to take much longer.

Current IMF forecasts (IMF 2013) show a positive outlook for the economies of the EAC (see figure 5.16). However, its countries will have to focus on reducing poverty and inequality in order to establish a middle class that can afford air transport.

Figure 5.16 Forecasted GDP Per Capita Growth Rate in EAC Countries

Source: Calculation based on International Monetary Fund (IMF 2013).

Note: Base gross domestic product (GDP) in current prices, U.S. dollars. Year when estimate starts varies by country: Tanzania, 2006; Kenya, 2010; Rwanda, 2010; Burundi not applicable. EAC = East African Community.

Population in the EAC has been continuously growing in recent years, with average growth rates ranging from 2.6 percent to 3.4 percent between 2007 and 2012 (see figure 5.17). Uganda and Burundi achieved the highest growth rate, with Uganda having the second highest fertility rate globally. Some organizations, such as the United Nations Population Fund (UNPF), have voiced concerns about this development, given that EAC countries still face challenges in providing the required education and employment for a growing younger generation (Emorut 2012b).

Figure 5.17 Population Growth in EAC, 2007–12

Source: World Bank 2013c.

Note: EAC = East African Community.

Population growth will be accompanied by a shift in migration from rural to urban environments. Urbanization has increased consistently between 2007 and 2012 (see figure 5.18). Tanzania’s urban population represents over a quarter of its total population, with 8 percent of the population found in Dar es Salaam. Urbanization in Burundi is still low at 11 percent, with 90 percent of the population consisting of self-subsistence farmers. Similarly, Uganda has large populations in rural lands tending to the agricultural exports (for example, coffee, cotton, tea) of the country. The primary sector employs 75 percent of the country’s work force (Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2007).

Urbanization has been seen as a key driver for economic growth, and consequently the development of air transport markets, particulary in Kenya and Tanzania. In both markets, urbanization is expected to grow, with forecasts for Kenya showing that by 2033, its population will be equally distributed between urban and rural areas (World Bank 2011b). Much of this urbanization will however be concentrated in few locations, particularly in Kenya where Nairobi and Mombasa represent the only cities with a population above one million and Kisumu, the third largest city, recording a population of only 400,000.

As outlined in chapter 4, LCCs primarily target leisure travelers, who are cost sensitive but more amenable with regard to service offerings and scheduling. This allows LCCs to operate with greater flexibility and limits operational complexity. The leisure category includes in particular tourist and visiting friends and relatives (VFR) travelers.

East Africa with its national parks, mountain ranges, and scenic beaches has become a popular destination for tourism. As figure 5.19 shows, the number of international arrivals has grown considerably in most EAC countries.

Uganda has shown particularly high growth, which can be attributed to the increase of tourists from Asia to its famous national parks, and its relative political stability and security (Emorut 2012a). Both Tanzania and Rwanda have also experienced increasing visitors between 2006 and 2010. Rwanda, after having restructured its tourism sector in 2001, has been particularly focused on attracting high-end customers. This has been reflected in the major private investments that have been made to upgrade accommodations in the market. Both Marriott and Sheraton hotel chains are constructing 5-star facilities for US$160 million and employing about 200 people (Rwigamba 2013). Kenya’s tourism industry experienced a large drop in arrivals in 2007 and 2008 due to the outbreak of violence and political instability, triggered by the events following the 2007 Kenyan elections. The industry is recovering, however, and recorded almost 1.5 million international tourists in 2010 (UNWTO 2011). Burundi is still lagging considerably behind due to years of civil strife and limited tourism infrastructure.

EAC tourism is dominated primarily by European and American visitors. In Kenya, for example, the Kenya Tourism Board found that in 2010 almost half of its tourists originated from only five countries (the United Kingdom, the United States, France, Italy, and Germany) (Kenya Ministry of Tourism 2010). In Tanzania, a survey by the Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics and the Bank of Tanzania also showed that arrivals from Italy, the United States, the United Kingdom, and Germany dominate the tourism market (Tanzania National Bureau of Statistics 2012). More recently, intra-African and intra-EAC tourism have also been recorded. In Kenya, recorded tourist arrivals from Uganda and Tanzania were 33,900 and 30,264 visitors respectively (Kenya Ministry of Tourism 2010) and in Rwanda around 40 percent of visitors originated from the region in 2010. Only 5 percent traveled for tourism purposes however (Rwanda Development Board n.d.). Similarly, in Uganda arrivals from Africa seem to dominate its market but only 5 percent are tourists (Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2010), while European visitors primarily dominate the tourism market (Balinda 2013). No equivalent information could be found for the tourism market in Burundi.

According to the World Tourism and Travel Council, tourism is forecast to grow considerably in the region. Between 2013 and 2023, international tourist arrivals in Kenya are set to grow to 2.6 million visitors (World Travel and Tourism Council 2013a). Similarly, for Rwanda this growth rate is forecast at around 4.6 percent (World Travel and Tourism Council 2013b). Expected growth is even higher in Uganda (World Travel and Tourism Council 2013c) and in Tanzania (World Travel and Tourism Council 2013d), at about 5.6 percent and 5 percent respectively.

This growth will be of particular importance, as tourism plays a crucial role in the economies of the EAC. As figure 5.20 shows, for Rwanda and Uganda, tourism comprises a large percentage of their exports.

Figure 5.20 International Tourism Receipts, 2010

percentage of total exports

Source: World Bank 2013c.

Significant efforts have therefore been made to facilitate intra- and inter-regional tourism. The EAC Secretariat is trying, for example, to remove restrictive customs and border control processes to facilitate travel in the region. To this end, all EAC member states met in July 2013, to outline new milestones for the introduction of a common EAC tourism visa, as well as a common passport for EAC member countries. The proposal has been deliberated since 2005, but has experienced significant delays resulting from security concerns, poor infrastructure, and disagreement over visa fee schedules and revenue-sharing frameworks. Leaving time to resolve these issues, the changes are now planned to be introduced by the end of 2014. In an initial step, all EAC countries have agreed to align their immigration laws and to put into place the technology needed for integrating their information network systems (Ramah 2013). These changes will also be a key factor for another known source of LCC demand, the so-called VFR travel resulting from intra-regional migration flows.

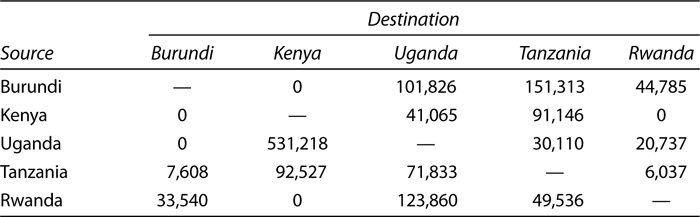

According to a 2011 World Bank study, more than 50 percent of migration in East Africa actually occurs within the region (Ratha and others 2011). Table 5.2 shows the migration stocks of EAC member countries as collated in the World Bank’s Migration and Remittances Factbook 2011 (World Bank 2011c). Unfortunately, data on migration in Africa are often missing, out-of-date, or inconsistent with definitions used in other countries. Therefore, such data should be interpreted with caution. For example, it is surprising to see that no migrants have been recorded from Burundi to Kenya.

Table 5.2 Estimates of Bilateral Migrant Stock, 2010

Source: Migration and Remittances Factbook (World Bank 2011b).

Note: — = not available.

Migration within the EAC has occurred because of several reasons. These are primarily economic (for example, employment and education) and/or political (that is, civil unrest, political instability). Assessing various patterns of migration within the region is very complex and would be outside the scope of this book. However, a few key developments that may potentially have an impact on future air travel demand are reviewed below.

One important factor for migration within the EAC has been the economic integration and free movement of labor in the region through the EAC Treaty. This has been particularly attractive for smaller, less developed, and historically unstable countries, such as Burundi and Rwanda. For example, Rwandese nationals, spurred by forced migration during the Rwanda Genocide in 1994, have a substantial presence in Uganda, Tanzania, and neighboring Burundi. Movements are further facilitated by language, cultural, or historical ties. Emigrants from Burundi and Rwanda, for example, often speak the same language as or have historical ties with the native populations in Uganda and Tanzania (Ratha and others 2011). High levels of migration have also been observed between Uganda and Kenya, potentially contributing to the increased traffic on the Entebbe (EBB) to Nairobi (NBO) route. The economic integration of the region and the introduction of a common passport are expected to further increase this growth.

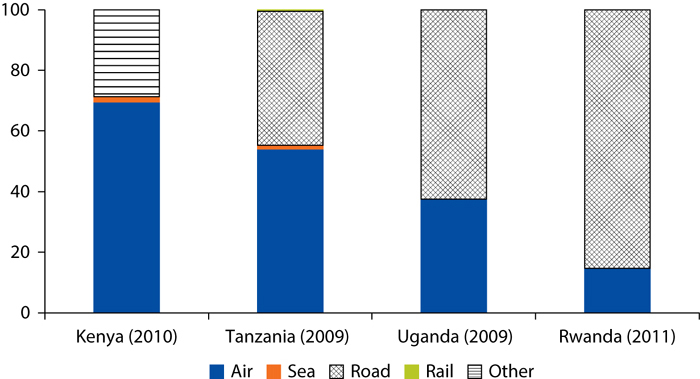

Inefficient ground transport has been a key driver for the development of air transport and LCCs in developing countries. Figure 5.21 compares the numbers of visitors arriving by each mode of transport. It shows clearly that in Rwanda and Uganda, and to a lesser extent in Tanzania and Kenya, arrivals are often by land transport. The more detailed statistics for Rwanda show that land access is particularly prevalent for tourists. In 2011, 61 percent of arrivals by passengers traveling for tourism purposes entered by land (Rwanda Institute of Statistics 2012).

Figure 5.21 Arrival by Mode of Transport

percent

Sources: Analysis based on data from Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (2010); Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2010; National Institute of Statistics Rwanda 2012; and Tanzania Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism 2010.

Note: Definition of mode may vary. In Kenya “other” includes rail and road transport.

Kenya displays a high share of arrivals by air, mostly due to traffic through the region’s hub in Nairobi (Kenya National Bureau of Statistics 2010).

In order to understand the market opportunities for “converting” land-based transport users to air travelers, it is important to look at the availability, quality, and cost of these means of transport. To assess this, the book draws upon an extensive analysis of transport infrastructure in the region conducted by the World Bank in 2011 (Ranganathan and Foster 2011).

As map 5.2 shows, EAC regional corridors are typically paved (around 73 percent of all roads are paved) and almost 80 percent of regional roads are in good or fair condition. Although few, there are some road segments of poor quality and significant unpaved stretches, as for example on the Dar es Salaam to Bujumbura route or on the Kampala to Kigali route. The poor condition of these roads slows traffic considerably.

Generally, all EAC members except Uganda show good maintenance records on their portions of the regional network. The EAC, together with development partners such as the African Development Bank, the Japanese Bank for International Cooperation, and the World Bank have focused on improving road conditions under the East African Road Network Project and other programs (NEPAD–OECD Africa Investment Initiative 2008).

Generally road infrastructure between larger cities in the EAC is in good condition, but the quality of rural roads providing access to primary roads, still varies significantly. A rural road condition assessment by the Africa Infrastructure Country Diagnostics (AICD) program (in Gwilliam and others 2011) shows that the quality of rural roads in the region is still poor. Among EAC states, Rwanda’s rural network is assessed the worst—with poor quality, rural roads across its entire network. In Uganda, over 50 percent of rural roads (by length) are still considered to be of inferior quality, whereas in Tanzania, Kenya, and Burundi, the share of poor quality rural roads falls below 50 percent. Kenya is the country with the most high quality roads in the region, followed by Burundi.

Map 5.2 Road Network: Major Primary Road by Type and Condition

Source: World Bank’s East Africa Infrastructure Report (World Bank 2011a).

The use of passenger cars is still low in the EAC. In Rwanda, there were only 0.5 cars per 1,000 inhabitants in the year 2007, 2 in Burundi, 4 in Tanzania and 3 in Uganda. Kenya has the highest rate with 14 passenger cars per 1,000 inhabitants in 2010. This compares to 423 cars per 1,000 inhabitants in the United States and 457 in the United Kingdom for the same year. As access to passenger cars is still limited, reliance is high on other forms of ground transport, including buses and trains. There are various companies providing bus services in the region, primarily connecting major cities. A prominent provider is Scandinavia Express, offering high frequency bus service to 18 destinations within Tanzania, Kenya, Uganda, and Zambia. A one-way fare from Dar es Salaam to Nairobi costs around US$23, and between Kampala and Nairobi about US$30 (Scandinavia Express 2013). Two other Kenyan companies, Mash and Easy Coach primarily offer bus operations within Kenya and to Kampala. According to the Easy Coach website, a fare between Nairobi and Kampala is offered at US$27 (Easy Coach 2013). Some bus companies, such as the Riverside shuttle, have been particularly geared toward connecting incoming tourism at Nairobi Airport to destinations such as Kilimanjaro, offering competitive fares of US$20 for a one-way trip. This makes land transport in some cases, and on this route in particular, an attractive alternative and a significant competitor for LCCs.

Despite the availability of alternative modes of ground-based transport on certain routes, road safety is still a large concern in Africa. In 2010, the World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that nearly 8,484 people were killed on Kenyan roads in 2010 (WHO 2013). This translates into a death rate of 20.9 per 100,000 people. In contrast the United States and the United Kingdom, with much higher usage of cars, have death rates of 11.4 and 3.7 per 100,000 people respectively.

The EAC region does not have a truly integrated rail network, and only three railway lines run across more than one country, with the one linking Kenya to Uganda being the only one linking EAC countries. The quality of railways in EAC is relatively low, with little maintenance having been undertaken. Moreover railway infrastructure is only capable of light and slow-moving trains, and regional operations are difficult due to differing railway gauges in each country.

There are only a few efficient railway operators in the region. Tanzania’s two operators, Tanzania Railways Limited (TRL) and Tazara, have been showing some signs of success in past years, but both operators are still lagging behind the Rift Valley Railways (RVR) consortium that operates between Kenya and Uganda. The railway concession, financed by various donors including the African Development Bank and the International Finance Corporation (IFC) (Evans 2011) carried around 1.5 million tons in 2012 in comparison to less than half a million for both TRL and Tazara.

Table 5.3 Comparison of Bus Travel and Flight Times

Route |

Bus time (approx.) |

Flight time |

Nairobi–Mombasa |

8 hours |

1 hour |

Nairobi–Kampala |

12 hours |

1 hour, 8 minutes |

Nairobi–Dar es Salaam |

13 hours |

1 hour, 25 minutes |

Nairobi–Kigali |

24 hours |

1 hour, 22 minutes |

Entebbe–Kigali |

9 hours |

50 minutes |

Nairobi–Kisumu |

5 hours, 30 minutes |

50 minutes |

Dar es Salaam–Arusha |

9 hours |

1 hour, 25 minutes |

Source: Flight schedules and bus websites.

On the Dar es Salaam to Zanzibar route—a main gateway for tourism, air transport also competes with maritime transport. The route has a modern ferry service running four times daily with economy class fares of US$35.

Despite the availability of alternative modes of transport on certain routes, air travel has a significant advantage over each of them, that is, speed. Table 5.3 shows the travel times by bus and by plane between major cities in EAC. This excludes any delays, such as customs hold ups or journey interruptions, which could potentially add to total transport time.

A bus journey from Dar es Salaam to Nairobi takes around 13 hours, and almost a whole day between Nairobi and Kigali (Scandinavia Express 2013). In Kenya, the bus from Nairobi to Mombasa takes around 8 hours, and until the Uganda–Kenya railway is modernized, the rail journey takes around 15 hours (Evans 2011).

As elaborated in chapter 4, the availability—but most importantly the quality, capacity, and cost of air transport infrastructure—plays a crucial role for the development of LCCs and air transportation in general. This section provides an analysis of airports in the EAC region, focusing in particular on availability, quality, and capacity of airside,3 landside,4 CNS (communications, navigation, and surveillance) infrastructure, and ground handling, as well as airport management and usage costs. In addition, factors relating to airport access will be reviewed.

With the exception of the World Economic Forum’s annual quality of air transport infrastructure report, there are few indexes that measure the overall quality of air transport infrastructure. As figure 5.22 shows, Kenya’s air transport infrastructure is ranked the highest among EAC states, followed with a significant margin by Rwanda and Uganda. Tanzania and Burundi appear to have the lowest ranking air transport infrastructure.

Figure 5.22 Air Transport Infrastructure Quality, 2012/13

Source: World Economic Forum Global Competitiveness Report 2012–2013, Switzerland (WEF 2013).

Note: 7 – high quality, 1 – low quality.

Although this gives an indication of the overall quality of air transport infrastructure, large differences prevail between individual airports, requiring a more detailed assessment.

The EAC has a considerable number of airfields, particularly in Kenya and Tanzania. However, the majority of airfields have unpaved runways, and are, with few exceptions, unsuitable for commercial operations. For July 2012–13, only 10 percent of total airports actually received scheduled services and less than 40 percent are both paved and have the required runway length to accommodate regional jets, such as the fuel-efficient Embraer ERJ-170-100 (see table 5.4). In order not to impose major limitations, however, the sample chosen focuses on all airports which currently receive scheduled services, as well as other airports with paved and sufficiently long runways for operations of regional aircraft (based on ERJ-170-100). A list of all airports assessed and detailed information can be found in appendix G.

The majority of EAC airports receiving scheduled services, with the exception of some airports in Kenya (for example, Mara Serena Airport in Kenya), and Tanzania (for example, Bukoba Airport), have paved runways, taxiways, and aprons. Assessing their conditions remotely, however, is a difficult task. It is often based on a few high level indicators that can be evaluated from satellite imagery. This includes any patching that has been undertaken to cover previous pavement failures, which, when observed over a period of time, may be linked to ongoing condition issues. It is, however, in most cases impossible to identify any major signs of pavement failure, such as cracking, rutting or chip loss.

There are few reports available on runway conditions in the EAC. A report produced by the AICD program previously assessed the runway quality of major airports in Africa. It identified that the airports in the region receiving the highest volumes of traffic, for example Nairobi and Dar es Salaam, generally have higher quality runways of standard length for larger jet aircraft operations (AICD 2009).

CNS infrastructure in the EAC is still largely insufficient, but some progress has been achieved in recent years. The installation of ground-based navigation aids for en route and approach navigation is patchy, with only a bit more than half of the airports assessed having any installations. This often requires pilots to fly under visual flight rules (VFR), whereby pilots rely on the “see and avoid” rule and are dependent on clear weather conditions to ensure visibility. Most airports that have any ground-based navigation aids are equipped with simple nondirectional beacons (NDBs) or in some cases with additional, more sophisticated VHF omnidirectional range (VOR) systems. Few VOR installations are complemented with distance measuring equipment (DME), which aids aircraft pilots in determining the exact distance from the land-based navigation aids, further improving navigation precision. Installations for aircraft approach and landing such as instrument landing systems (ILS), precision approach path indicators (PAPI), and more sophisticated lighting systems are common only at major airports such as Nairobi, Dar es Salaam, or Entebbe.

Radar installations for surveillance and air traffic management (ATM) are rare due to high equipment and maintenance costs. Some airports such as Dar es Salaam and Nairobi have secondary radar installations, and Mombasa can use radar procedures if required (Gwilliam and others 2011). Uganda installed a new secondary radar for EUR7 million in 2006.5 The radar is also able to monitor parts of the airspace in neighboring Rwanda, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kenya, and Tanzania—but does not provide any services to aircraft operating in those airspaces (Kazooba 2007).

Whether or not all of these installations are actually operational is unknown. This is related to the fact that the necessary information for pilots that would indicate the failure of any equipment, so-called NOTAMS (notices to airmen), are not being issued consistently or are not publicly available.

The lack of ground-based navigation aids and radar is still a critical weakness at this point in time. However, it is seemingly becoming a smaller issue due to the development of satellite-based navigation and surveillance systems. Although NDB and VOR remain common in developed countries, most modern aircraft rely now on global navigation satellite systems (GNSS). GNSS approaches are already being used at the major airports in Dar es Salaam and Nairobi. A pilot study to introduce GNSS procedures throughout the EAC has been undertaken with U.S. government funding in 2006. The EAC has formulated a plan to introduce GNSS procedures at three airports of each community member, which has yet to be implemented (EAC n.d.).

GNSS also provides the basis for modern surveillance technology, such as the automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast system (ADS-B). ADS-B is a more advanced and cost-effective substitute to today’s radar system, and is currently being implemented in the United States, Europe, Australia and a few other countries. It has also been considered in the EAC, with Tanzania recently announcing the implementation of ADS-B at its air traffic control (ATC) center in Dar es Salaam (Comsoft 2013).

Communications infrastructure (ground-to-air and ground-to-ground) has improved considerably, and all EAC countries have benefited from regional communications projects such as the SADC Very-Small Aperture Terminal (VSAT) Network, which covers Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi, as well as the North Eastern African Indian Ocean VSAT (NAFISAT) network covering Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya (Air Traffic and Navigation Services 2013). VSAT is a technology used to define two-way satellite communications, to transmit and receive data from a relatively small satellite dish on earth, and communicate with an orbiting geostationary satellite.

The management of air traffic lies with a designated provider in the respective flight information region (FIR). The EAC region is divided into five FIRs (Nairobi FIR, Dar es Salaam FIR, Entebbe FIR, Kigali FIR, and Bujumbura FIR) each with a designated ATM provider. With the exception of the Bujumbura FIR that relies on Dar es Salaam to provide ATM for its upper air space, each of the respective ATM providers is responsible for upper and lower air space.6 Rwanda, whose upper air space was historically also managed by Tanzania, has recently announced that it will be taking over control of its upper air space (Muson 2009). Currently ATM services are provided by the specialized departments of the respective civil aviation authority (CAA) in each country. The respective CAA also provide approach and aerodrome control at major airports, as well as aerodrome flight information services (AFIS) on some secondary airports.

Multiple initiatives have been introduced to improve CNS capabilities in the region. COMESA has launched an integrated air space project with the financial support of the African Development Bank. The project’s objective is to develop (a) a legal and regulatory framework for a unified upper airspace in the COMESA Region; (b) an adequate institutional framework for providing and regulating regional air traffic services; and (c) public-private partnership arrangements to finance, build, and operate the regional communications, navigation, and surveillance systems for air traffic management (CNS/ATM) infrastructure (African Development Bank 2011a). Simultaneously, the EAC Secretariat has been working toward a regional upper flight information region (UFIR) governing the upper air space of all EAC members, thereby enhancing safety and efficiency and allowing for a seamless flow of traffic (CASSOA 2013). Trying to integrate all of these efforts within the region, the COMESA-EAC-SAD Tripartite has been developing a strategy for the seamless integration of all upper air space between the three RECs (OECD and WTO 2011).

There is often little public information available about the condition of landside infrastructure, especially passenger terminals, in EAC. Many airport facilities in the region have relatively old (for example, Entebbe or Dar es Salaam), limited, or in some cases no passenger facilities (for example, Lodwar Airport). Many of the smaller airports also do not have any or only part-time customs or immigration facilities required for international traffic. Whereas outdated and deteriorated infrastructure may be a significant issue at the country’s main gateways, smaller airports with little traffic do not, in most cases, require any lavish airside facilities as long as safety and security standards can be ensured.

As described in chapter 4, most large airports in developed countries use various metrics to determine the level of service (LOS). These include aspects such as waiting and processing times and available space. This often relies on data-intense and costly primary research, for example through surveys, which are unavailable for this case.

When unable to obtain the needed data to quantitatively assess the quality of landside infrastructure, customer reviews provide for an alternative qualitative, albeit less scientific view. Skytrax, for example, a commonly known source for airport rankings, covers some of the larger airports in the region such as Nairobi, Mombasa, Dar es Salaam, Entebbe, or Kigali. As the number and timing of reviews vary and are subject to personal opinions, caution is warranted. However, the ranking serves as an interesting indicator of passenger perception. Both Entebbe and Kigali rank high in their reviews (achieving 7.3 and 8 out of 10 points), whereas Bujumbura, Jomo Kenyatta, and Mombasa achieve low scores, particularly due to slow processing times and the general quality of facilities (Skytrax 2013).

A crucial factor in assessing the current quality of infrastructure and prospects for the development of air services is available capacity. As outlined in chapter 1, LCCs avoid highly congested airports because of the costs associated with delays and inflexible scheduling. In order to assess the current utilization of airports and potential for growth, it is necessary to look at both airside and landside capacity of a given airport.

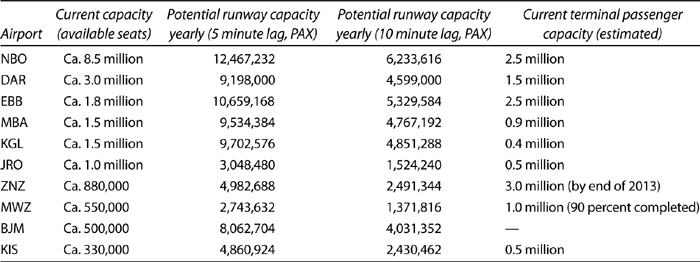

Table 5.5 Potential Runway Capacity per Year (5 Minute and 10 Minute Lags) and Current Estimated Passenger Terminal Capacity

Sources: Calculation based on DiiO SRS Analyzer (2013), and AZ World Airports Passenger Capacity (2013b).

Note: BJM = Bujumbura, Burundi; DAR = Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; EBB = Entebbe, Uganda; JRO = Kilimanjaro, Tanzania; KIS = Kisumu, Kenya; KGL = Kigali, Rwanda; MBA = Mombasa, Kenya; MWZ = Mwanza, Tanzania; NBO = Nairobi; PAX = passengers; ZNZ = Zanzibar, Tanzania; — = not available.

Table 5.5 shows the current and potential estimated capacity of the region’s largest airports by movement (see appendix H for methodology on runway and terminal capacity estimations). Setting aside constraints posed by apron capacity, the estimates show that almost none of the airports in this sample have reached their potential runway capacity when assuming a five-minute time lag between each flight. When assuming a longer time lag of ten minutes between operations, the only airport that has already exceeded runway capacity is Jomo Kenyatta Airport in Nairobi. Thus, additional runway capacity appears not to be required for most airports. Instead, the focus should be on rehabilitation of current infrastructure, and on possible apron extensions, as well as on more effective scheduling and potential relocation of taxiways to enable a more efficient flow of traffic. It should be noted that these estimates are based on the current average capacity per operation, and runway extensions required for the operation of larger aircraft may be warranted if traffic increases dramatically.

Although the figures show that runway capacity does not pose a major challenge for airport operations, passenger terminal capacity appears to be greatly constraining air traffic. Most passenger terminals were not built to handle the increase in passengers, as experienced at some airports, particularly in Nairobi, Dar es Salaam, Kigali, and Zanzibar.

Recognizing the constraints of landside facilities, major investment projects have been initiated in the region. This includes the expansion of Jomo Kenyatta Airport, partially financed by the World Bank, which includes a new terminal and possibly a new runway, increasing the number of potential movements. The Kenyan government has also been upgrading smaller airports, such as the Mandan Airstrip in Lamu, which included the construction of a two-kilometer runway, a new terminal building, additional water supplies, and fencing, as well as a new fire station (Ventures 2013).

Tanzania is currently refurbishing and upgrading 10 regional airports under a US$67.5 million infrastructure project (Mbalamwezi 2011), and is investing US$170 million to build Terminal 3 for Julius Nyere Airport in Dar es Salaam. The existing international Terminal 2 will then be used for domestic flights (allAfrica 2013). Under the World Bank’s Tanzania Transport Sector Support Project, the country is also paving and rehabilitating the runway at Kigoma and Tabora Airports, and extending, rehabilitating, and paving the runway, apron, terminal, and car parking at Bukoba Airport.

In Rwanda, the government is finalizing talks with a Chinese firm to construct the Bugesera International Airport, which will serve as a complementary airport for Kigali, located 25 kilometers east of the capital (Ssuuna 2013). Kigali, having reached its maximum capacity according to authorities, is also currently being upgraded to cater to higher passenger volumes.

Finally, the government of Uganda has announced, in its 20-year civil aviation master plan in 2013, a US$400 million project to modernize Entebbe airport facilities as well as smaller domestic airports such as Kasese, Gulu, Arua, and Kotido (Muchira 2013). These are just a few examples of ongoing projects, which are increasing the capacity of the aviation system in EAC.

The provision of ground handling services varies significantly across EAC countries. Kenya has a competitive ground handling services industry with 15 different passenger and cargo ground handling providers, both local and international. Although companies provide varying offerings, competition appears to exist across almost all service categories (for example, ramp, passenger services, load control and support, and so on), with the notable exception of fueling services (Airline Update n.d.). This has significantly driven costs down, but could be unsustainable in the long term (World Bank 2005). Tanzania, after years of a ground handling monopoly with the firm Swissport Tanzania (previously Dahaco), has finally allowed competition to enter the market in 2009 (Tanzania Civil Aviation Authority 2013a), although a few licenses have been granted a quasi-monopoly and high charges have remained. Similarly in Rwanda, the government has finally allowed a second ground handling provider to enter the market, with Rwandair Express having been the only service provider for many years (Airline Update n.d.). In Uganda, ground handling is managed by two companies, with airlines complaining about the high cost of service and potentially uncompetitive practices between Uganda’s CAA and one of the ground handling providers ENHAS (Muhumuza 2012). In Burundi, there is currently only one ground handling provider, Asjetflow (Airline Update n.d.). However, considering the low volumes of traffic, more ground handling providers may be not feasible.

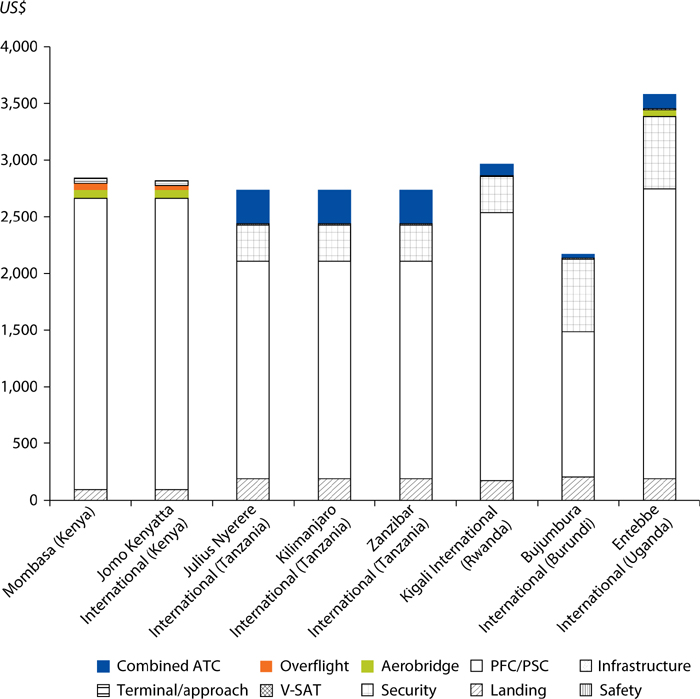

As seen in the case studies of South Africa and Mexico, high levels of airport charges can pose a considerable challenge for the development of LCCs. The analysis here assesses current infrastructure charges at EAC countries, and benchmarks these against similar airports in the region and globally (see appendix I for methodology including base case scenario and more detailed charges assessment).

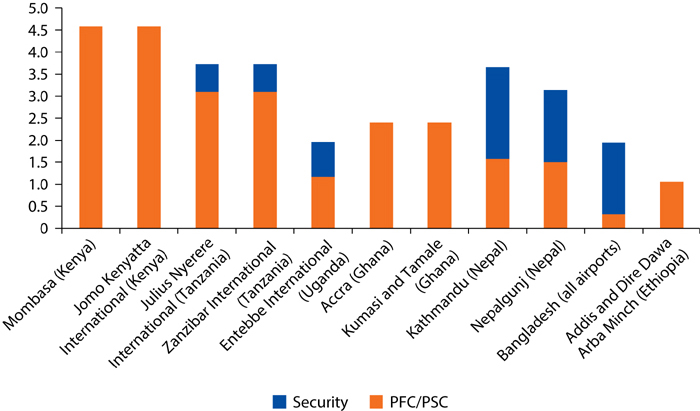

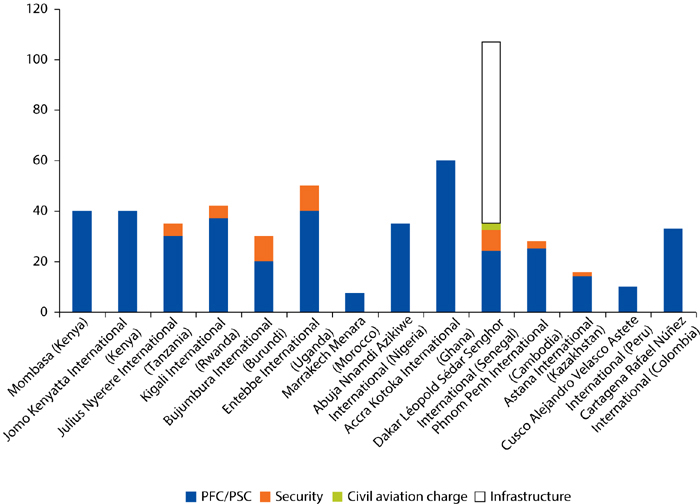

The level of airport charges at EAC airports varies considerably in relation to destination and type of charge (passenger borne or airline borne). Figure 5.23 compares airport charges for a sample of airports in EAC for domestic operations. As the analysis shows, airport charges for domestic operations are particularly high in Rwanda, driven strongly by high passenger facility charges/service charges (PFC/PSC).

Figure 5.23 Total Turnaround Charges for Domestic Daytime Flight

US$

Sources: Analysis based on aeronautical information publications from Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, and airport websites.

Note: Domestically registered ATR72-500, maximum takeoff weight 23 tons, 74 passengers at 80 percent load factor, turnaround time two hours. The methodology and data sources used for the calculations of charges are described in more detail in appendix I. ATC = air traffic control; PFC = passenger facility charge; PSC = passenger service charge.

Figure 5.24 Total Turnaround Charges for Regional/International Daytime Flight

US$

Sources: Analysis based on aeronautical information publications from Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, and airport websites.

Note: Internationally registered ERJ-170, maximum takeoff weight 37 tons, 80 passengers at 80 percent load factor, turnaround time two hours. ATC = air traffic control; PFC = passenger facility charge; PSC = passenger service charge; V-SAT = Very Small Aperture Terminal (satellite communications).

For regional or international operations, figure 5.24 shows that Entebbe has the highest turnaround cost of the sample, charging over US$3,500 per aircraft. Airport charges in Tanzania and Kenya appear to be at a similar level of around US$2,700, and slightly lower in Burundi at approximately US$2,100.

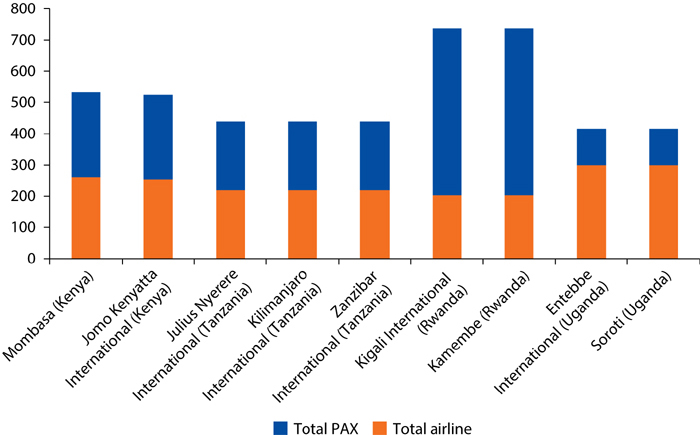

In order to weigh the cost for airlines versus passengers, all costs are aggregated for each category. Figure 5.25 shows that for domestic operations, charges are more equally distributed between passenger and airline charges in Kenya and Tanzania, whereas in Uganda the majority of charges are absorbed by the airline. In Rwanda, by contrast, the majority of costs are borne by passengers.

Figure 5.25 Total Turnaround Cost for Domestic Daytime Flight—Passengers versus Airlines

US$

Sources: Analysis based on aeronautical information publications from Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, and airport websites.

Note: Domestically registered ATR72-500, maximum takeoff weight 23 tons, 74 passengers at 80 percent load factor, turnaround time two hours. PAX = passengers.

For international operations, passenger charges significantly outweigh charges paid by airlines (see figure 5.26). For LCCs this means that load factors have little impact on their overall charges level, and the profitability of airlines is less sensitive to load factors (IFC 2013). Total turnaround charges vary between approximately US$2,100 at Bujumbura International to approximately US$3,600 at Entebbe International.

Figure 5.26 Total Turnaround Cost for Regional/International Daytime Flight—Passengers versus Airlines

US$

Sources: Analysis based on aeronautical information publications from Kenya, Rwanda, Tanzania, Uganda, Burundi, and airport websites.

Note: Internationally registered ERJ-170, maximum takeoff weight 37 tons, 80 passengers at 80 percent load factor, turnaround time two hours. PAX = passengers.

Although this analysis provides an indication of the level of charges in the intra-regional and domestic EAC markets, it gives little indication as to whether these charges are comparable to other airports or countries in the region or even globally. Comparing domestic and even regional charges on a more global scale is difficult because of the differing characteristics of each market, something that applies even to comparisons within the EAC region. It is also important to recognize that aeronautical charges are, in many cases, set as a form of cost-recovery or on a cost-plus basis. Airports with recent infrastructure investments, as for example in Senegal, are required to repay high debt services costs and therefore charge much higher aeronautical charges.