The web has been around for more than 25 years now, experiencing euphoric early expansion, an economic-driven bust, an innovation-driven rebirth, and constant evolution along the way. One thing is certain: the web as a communication and commercial medium is here to stay. Not only that, it has found its way onto devices such as smartphones, tablets, TVs, and more. There have never been more opportunities to put web design know-how to use.

Through my experience teaching web design courses and workshops, I’ve had the opportunity to meet people of all backgrounds who are interested in learning how to build web pages. Allow me to introduce you to just a few:

“I’ve been a print designer for 17 years, and now I am feeling pressure to provide web design services.”

“I’ve been a programmer for years, but I want shift my skills to web development because there are good job opportunities in my area.”

“I tinkered with web pages in high school and I think it might be something I’d like to do for a living.”

“I’ve made a few sites using themes in WordPress, but I’d like to expand my skills and create custom sites for small businesses.”

Whatever the motivation, the first question is always the same: “Where do I start?” It may seem like there is a mountain of stuff to learn, and it’s not easy to know where to jump in. But you have to start somewhere.

This chapter provides an overview of the profession before we leap into building sites. It begins with an introduction to the roles and responsibilities associated with creating websites, so you can consider which role is right for you. I will also give you a heads-up on the equipment and software you will be likely to use—in other words, the tools of the trade.

Where Do I Start?

Maybe you are reading this book as part of a full course on web design and development. Maybe you bought it to expand your current skill set on your own. Maybe you just picked it up out of curiosity. Whatever the case, this book is a good place to start learning what makes the web tick.

There are many levels of involvement in web design, from building a small site for yourself to making it a full-blown career. You may enjoy being a “full-stack” web developer or just specializing in one skill. There are a lot of ways you can go.

If you are interested in pursuing web design or production as a career, you’ll need to bring your skills up to a professional level. Employers may not require a web design degree, but they will expect to see working sample sites that demonstrate your skills and experience. These sites can be the result of class assignments, personal projects, or a site for a small business or organization. What’s important is that they look professional and have well-written, clean HTML; style sheets; and scripts behind the scenes.

If your involvement is at a smaller scale—say you just have a site or two you’d like to publish—you may find using a template on an online website service is a great head start (see the sidebar “I Just Want My Own Site”). Most allow you to tweak the underlying code, so what you learn in this book will help you customize the template to your liking.

I Just Want My Own Site

It Takes a Village (Website Creation Roles)

When I look at a site, I see the multitude of decisions and areas of expertise that went into building it. Sites are more than just code and pictures. They often begin with a business plan or other defined mission. Before they launch, the content must be created and organized, research is performed, design from the broadest goals to finest details must happen, code gets written, and everything must be coordinated with what’s happening on the server to bring it to fruition.

Big, well-known sites are created by teams of dozens, hundreds, or even thousands of contributors. There are also sites that are created and maintained by a team with only a handful of members. It is also absolutely possible to create a respectable site with a team of only yourself. That’s the beauty of the web.

In this section, I’ll introduce you to the various disciplines that contribute to the creation of a site, including roles related to content, design, and code. You may end up specializing in just one area of expertise, working as part of a team of specialists. If you are designing sites on your own, you will need to wear many hats. Consider that the day-to-day upkeep of your household requires you to be part-time chef, housecleaner, accountant, diplomat, gardener, and construction worker—but to you it’s just the stuff you do around the house. As a solo designer, you’ll handle many web-related disciplines, but it will just feel like the stuff you do to make a website.

Content Wrangling

Anyone who uses the title “web designer” needs to be aware that everything we do supports the process of getting the content, message, or functionality to our users. Furthermore, good writing can help the user interfaces we create be more effective, from button labels to error messages.

Of course, someone needs to create all that content and maintain it—don’t underestimate the resources required to do this successfully. Good writers and editors are an important part of the team. In addition, I want to call your attention to two content-related specialists in modern web development: the Information Architect (IA) and the Content Strategist.

Information architecture

An Information Architect (also called an Information Designer) organizes the content logically and for ease of findability. They may be responsible for search functionality, site diagrams, and how the content and data are organized on the server. Information architecture is inevitably entwined with UX and UI design (defined shortly) as well as content management. If you like organizing or are gaga for taxonomies, information architecture may be the job for you. The definitive text for this field as it relates to the web is Information Architecture: For the Web and Beyond, by Louis Rosenfeld and Peter Morville (O’Reilly).

Content strategy

When the content isn’t right, the site can’t be fully effective. A Content Strategist makes sure that every bit of text on a site, from long explanatory text down to the labels on buttons, supports the brand identity and marketing goals of the organization. Content strategy may also extend to data modeling and content management on a large and ongoing scale, such as planning for content reuse and update schedules. Their responsibilities may also include how the organization’s voice is represented on social media. A good place to learn more is the book Content Strategy for the Web, 2nd Edition, by Kristina Halvorson and Melissa Rich (New Riders).

All Manner of Design

Ah, design! It sounds fairly straightforward, but even this simple requirement has been divided into a number of specializations when it comes to creating sites. Here are a few of the job descriptions related to designing a site, but bear in mind that the disciplines often overlap and that the person calling herself the “designer” often is responsible for more than one (if not all) of these responsibilities.

User Experience, Interaction, and User Interface design

Often, when we think of design, we think about how something looks. On the web, the first matter of business is designing how the site works. Before you pick colors and fonts, it is important to identify the site’s goals, how it will be used, and how visitors move through it. These tasks fall under the disciplines of User Experience (UX) design, Interaction Design (IxD), and User Interface (UI) design. There is a lot of overlap between these responsibilities, and it is not uncommon for one person or team to handle all three.

The User Experience designer takes a holistic view of the design process—ensuring the entire experience with the site is favorable. UX design is based on a solid understanding of users and their needs based on observations and interviews. According to Donald Norman (who coined the term), UX design includes “all aspects of the user’s interaction with the product: how it is perceived, learned, and used.” For a website or application, that includes the visual design, the user interface, the quality and message of the content, and even the overall site performance. The experience must be in line with the organization’s brand and business goals in order to be successful.

The goal of the Interaction Designer is to make the site as easy, efficient, and delightful to use as possible. Closely related to interaction design is User Interface design, which tends to be more narrowly focused on the functional organization of the page as well as the specific tools (buttons, links, menus, and so on) that users use to navigate content or accomplish tasks.

The following are deliverables that UX, UI, or interaction designers produce:

User research and testing reports

Understanding the needs, desires, and limitations of users is central to the success of the design of the site or web application. The approach of designing around the user’s needs is referred to as User-Centered Design (UCD), and it is central to contemporary web design. Site designs often begin with user research, including interviews and observations, in order to gain a better understanding of how the site can solve problems or how it will be used. It is typical for designers to do a round of user testing at each phase of the design process to ensure the usability of their designs. If users are having a hard time figuring out where to find content or how to move to the next step in a process, then it’s back to the drawing board.

Wireframe diagrams

A wireframe diagram shows the structure of a web page using only outlines for each content type and widget (Figure 1-1). The purpose of a wireframe diagram is to indicate how the screen real estate is divided and where functionality and content such as navigation, search boxes, form elements, and so on, are placed. Colors, fonts, and other visual identity elements are deliberately omitted so as not to distract from the structure of the page. These diagrams are usually annotated with instructions for how things should work so the development team knows what to build.

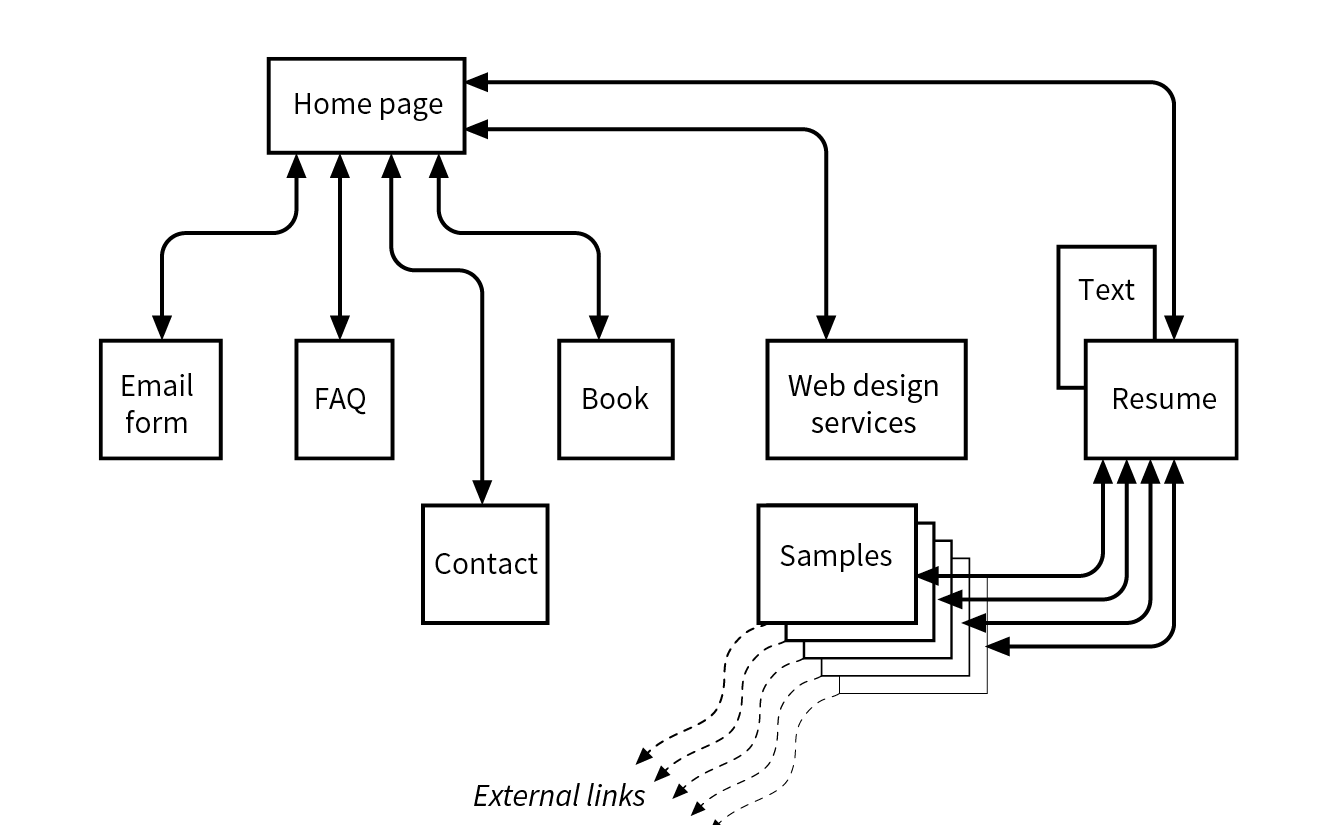

Site diagram

A site diagram indicates the structure of the site as a whole and how individual pages relate to one another. Figure 1-2 shows a very simple site diagram. Some site diagrams fill entire walls!

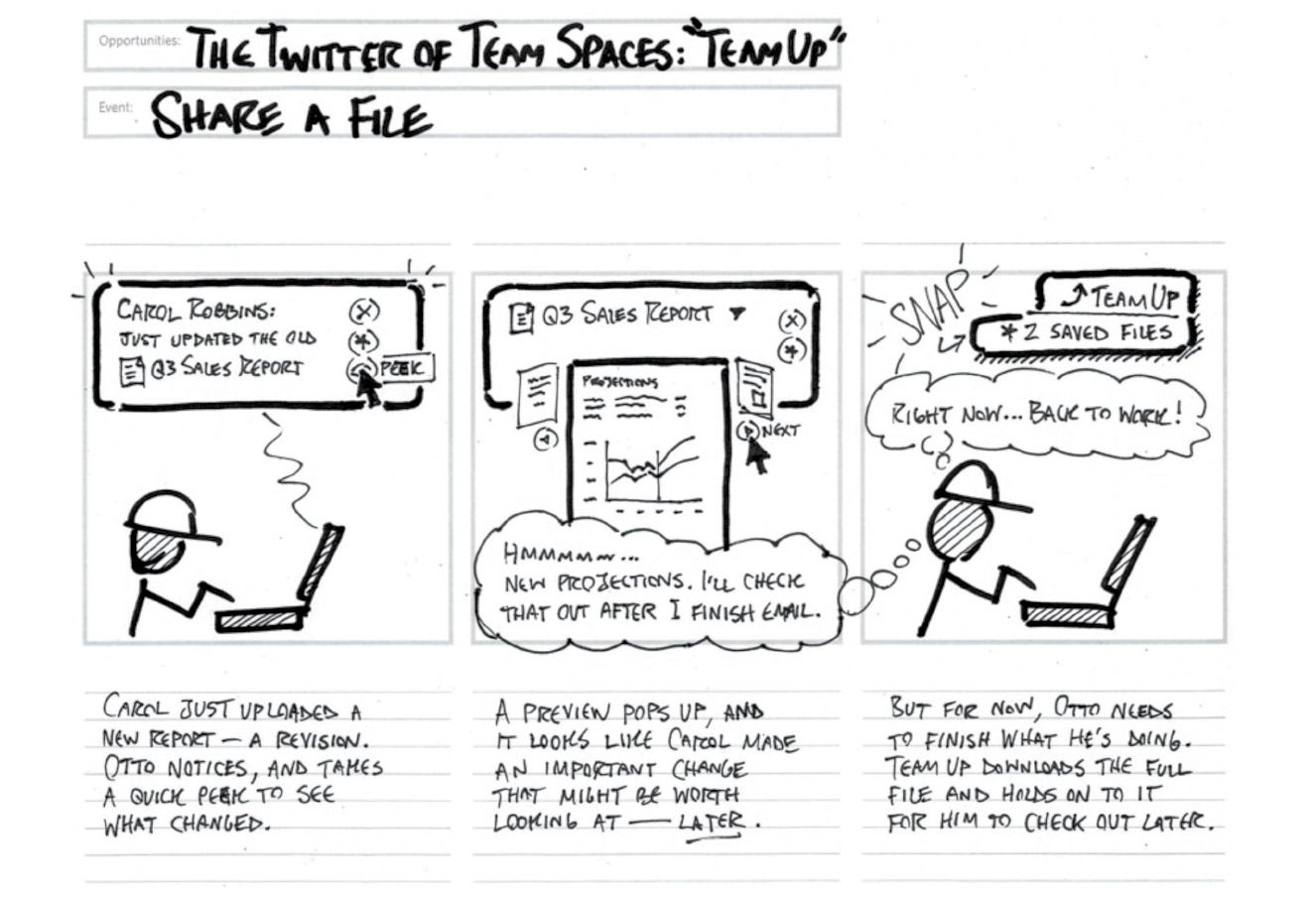

Storyboards and user flow charts

A storyboard traces the path through a site or application from the point of view of a typical user (a persona in UX lingo). It usually includes a script and “scenes” consisting of screen views or the user interacting with the screen. The storyboard aims to demonstrate the steps it takes to accomplish tasks, outlines possible options, and also introduces some standard page types. Figure 1-3 shows a simple storyboard. A user flow chart is another method for showing how the parts of a site or application are connected, but it tends to focus on technical details rather than telling a story. For example, “when the user does this, it triggers that function on the server.” It is common for designers to create a user flow chart for the steps in a process such as member registration or online payments.

There are many books on UX, interaction, and UI design, but these are a few of the classics to get you started:

- The Elements of User Experience: User-Centered Design for the Web and Beyond by Jesse James Garrett (New Riders)

- Don’t Make Me Think, Revisited: A Common Sense Approach to Web Usability by Steve Krug (New Riders)

- The Design of Everyday Things by Don Norman (Basic Books)

- About Face: The Essentials of Interaction Design, 4th Edition by Alan Cooper, Robert Reimann, David Cronin, and Christopher Noessel (Wiley)

- Designing Interfaces, 2nd Edition by Jenifer Tidwell (O’Reilly)

- 100 Things Every Designer Needs to Know about People by Susan Weinschenk (New Riders)

- Designing User Experience: A Guide to HCI, UX and Interaction Design by David Benyon (Pearson)

Visual (graphic) design

Because the web is a visual medium, web pages require attention to their visual presentation. First impressions are everything. A graphic designer creates the “look and feel” of the site—logos, graphics, type, colors, layout, and so on—to ensure that the site makes a good first impression and is consistent with the brand and message of the organization it represents.

There are many methods and deliverables that can be used to present a visual design to clients and stakeholders. The most traditional are sketches or mockups (created in Photoshop or a similar tool) of the way the site might look, such as the home page mockups shown in Figure 1-4.

Now that sites appear on screens of all sizes, many designers prefer to discuss the visual identity (colors, fonts, image style, etc.) in a way that isn’t tied to a specific layout like the typical desktop view shown in Figure 1-4. The idea is to agree upon a visual language for the site before production begins.

One option for separating style from screen size is to use style tiles, a technique introduced by Samantha Warren (see Note). Style tiles include examples of color schemes, branding elements, UI treatments, text treatment, and mood (Figure 1-5). Once the details are decided upon, they can be implemented into working prototypes and the final site. For more on this technique, visit Samantha’s excellent site, styletil.es, where you can download a template.

Graphic designers may also be responsible for producing the image assets for the site. They will need to know how to optimize images for the fastest delivery and how to address the requirements of varying screen sizes. It is also common for the development team to handle image optimization, but I think it is a skill every visual designer should have. We’ll discuss image optimization in Chapter 24, Image Asset Production.

Designers may also be responsible for creating a style guide that documents style choices, such as fonts, colors, and other style embellishments, in order to keep the site consistent over time. For a list of examples, articles, books, and podcasts about web style guides, visit the “Website Style Guide Resources” page at styleguides.io.

Code Slinging

A large share of the website building process involves creating and troubleshooting the documents, style sheets, scripts, and images that make up a site. At web design firms, the team that handles the creation of the files that make up the site (or templates for pages that get assembled dynamically) is usually called the development or production department.

Development falls under two broad categories: frontend development and backend development. Once again, these tasks may fall to specialists, but it is just as common for one person or team to handle both responsibilities.

Frontend development

AT A GLANCE

Frontend Development

Frontend refers to any aspect of the design process that appears in or relates directly to the browser. That includes HTML, CSS, and JavaScript, all of which you will need to have intricate knowledge of if you want a job as a web developer. Let’s take a quick look at each.

Authoring/markup (HTML)

Authoring is the process of preparing content for delivery on the web, or more specifically, marking up the content with HTML tags that describe its content and function.

HTML (HyperText Markup Language) is the authoring language used to create web page documents. The current version (and the version documented in this book) is HTML 5.2. Appendix D, From HTML+ to HTML5, tells the history of HTML and lists what makes HTML5 unique.

HTML is not a programming language; it is a markup language, which means it is a system for identifying and describing the various components of a document such as headings, paragraphs, and lists. The markup indicates the document’s underlying structure (you can think of it as a detailed, machine-readable outline). You don’t need programming skills—only patience and common sense—to write HTML.

The best way to learn HTML is to write out some pages by hand, as we will be doing in the exercises in Part II of this book.

Styling (CSS)

While HTML is used to describe the content in a web page, Cascading Style Sheets (CSS) describe how that content should look (see Note). The way the page looks is referred to as its presentation. Fonts, colors, background images, line spacing, page layout, and so on, are all controlled with CSS. You can even add special effects and basic animation to your page.

Note

When this book uses the term “style sheets,” it always refers to Cascading Style Sheets, the standard style sheet language for the World Wide Web. Style sheets (including what “cascading” means!) are discussed further in Part III.

The CSS specification also provides methods for controlling how documents will be presented in contexts other than a browser, such as in print or read aloud by a screen reader; however, we won’t be covering them much here.

Although it is possible to publish web pages using HTML alone, you’ll probably want to take on style sheets so you’re not stuck with the browser’s default styles. If you’re looking into designing websites professionally, either as a designer or as a developer, proficiency at style sheets is mandatory.

JavaScript and DOM scripting

JavaScript is a scripting language that adds interactivity and behaviors to web pages, including these (to name just a few):

- Checking form entries for valid entries

- Swapping out styles for an element or an entire site

- Loading scrolling feeds with more content automatically

- Making the browser remember information about users

- Building interface widgets, such as embedded video players or special form inputs

You may also hear the term DOM scripting used in relation to JavaScript. DOM stands for Document Object Model, and it refers to the standardized list of web page elements that can be accessed and manipulated using JavaScript (or another scripting language).

Frontend developers may also be required to be familiar with JavaScript frameworks (such as React, Bootstrap, Angular, and others) that automate a lot of the production process. They’ll likely also need to be handy with AJAX (which stands for “Asynchronous JavaScript And XML”), a technique used to load content in the background, allowing the page to update smoothly without reloading (like those automatically refreshing feeds).

Web scripting definitely requires some traditional computer programming prowess. While many web developers have degrees in computer science, it is also common for developers to be self-taught. A few developers I know started by copying and adapting existing scripts, then gradually added to their programming skills with each new project. Still, if you have no experience with programming languages, the initial learning curve may be a bit steep.

If you want to be a web developer for a living, JavaScript is a basic requirement. Designers will benefit from understanding what JavaScript can do, but may not need to learn to write it if they are working with a development team. Chapter 21, Introduction to JavaScript, will get you started understanding how it works, and I recommend Learning JavaScript by Ethan Brown (O’Reilly) to learn more.

The World Wide Web Consortium

Backend development

Backend developers focus on the server, including the applications and databases that run on it. They may be responsible for installing and configuring the server software (we’ll be looking more at servers in Chapter 2, How the Web Works). They will certainly be required to know at least one, and probably more, server-side programming languages, such as PHP, Ruby, .NET (or ASP.NET), Python, or JSP, in order to create applications that provide the functionality required by the site. Applications handle tasks and features like forms processing, content management systems (CMSs), and online shopping, just to name a few.

AT A GLANCE

Backend Development

Additionally, backend developers need to be familiar with configuring and maintaining databases that store all of the data for a site, such as the content that gets poured into templates, user accounts, product inventories, and more. Some common database languages include MySQL, Oracle, and SQL Server.

Backend development is well beyond the scope of this book, but it is important to know the sorts of tasks that get taken care of at the server level. You should be aware that it is possible to get functionality like shopping carts, mailing lists, and so on as prepackaged solutions from your hosting company without having to program it from scratch.

Full-Stack Developers and Unicorns

Other Roles

Not surprisingly, there are a myriad of other roles that contribute to the creation and maintenance of a site. Here are a few common roles that fall just outside the moniker “web design.”

Product manager

The product manager of a website or application guides its design and development in a way that meets business goals. This member of the team must have a thorough understanding of the target market as well as the processes involved in the creation of the site itself. Product managers develop the overall strategy for the site from a marketing perspective, including how and when it gets released.

Project manager

The project manager coordinates the designers, developers, and everyone else who is working on the site. They manage things like timelines, development approaches, deliverables, and so on. The project manager works with the product manager and other product owners to make sure that the project gets done on time and on budget.

SEO specialist

A website or application isn’t much good if nobody knows it exists, so it is crucial that a site be easily found by search engines. Search Engine Optimization (SEO) is a discipline focused on tweaking the site structure and code in a way that increases the chances it will be highly ranked in search results. There may be an SEO specialist on the in-house team, or a company may choose to hire an outside SEO firm. SEO is sometimes perceived as a dark art, but there are many ways to improve findability that are not underhanded. In fact, the number one technique for improving SEO is simply having good content with savvy HTML markup.

Multimedia producers

One of the cool things about the web is that you can add multimedia elements to a site, including sound, video, animation, and even interactive games. Creating multimedia elements is generally best left to artists and technicians in those fields, although they may be part of the web team if video, animation, or interactivity are core to the site’s mission.

That concludes our stroll through the virtual village of workers involved in the creation of a website. The larger the site, the more likely each team member will have a narrow specialization and job titles like “UX Lead for Error Messages.” More likely, everybody on the team will possess a spectrum of skills, and the lines between disciplines will blur. For example, I do Interaction and User Interface design, graphic design, HTML, and CSS, but I do not write JavaScript, work on the server, or get involved with content organization. In this book, I aim to give you a foundation in the frontend technologies that will prepare you for a number of roles.

(Soft) Skills Every Web Designer Needs

Gearing Up for Web Design

It should come as no surprise that professional web designers require a fair amount of gear, both hardware and software. One question I’m frequently asked is, “What do I need to buy?” I can’t tell you specifically what to buy, but I will provide an overview of the typical tools of the trade.

Equipment

For a comfortable web development environment, I recommend the following equipment:

A solid, up-to-date computer

Macintosh, Windows, or Linux is fine, so use whatever you have and are comfortable with. Creative departments in professional web development companies tend to be Mac-based. For backend work, Linux and Windows are popular. Although it is nice to have a super-fast machine, the files that make up web pages are very small and tend not to be too taxing on computers. Unless you’re getting into sound and video editing, don’t worry if your current setup is not the very latest and greatest.

A large monitor

Although not a requirement, a large monitor makes life easier. The more monitor real estate you have, the more windows and control panels you can have open at the same time. You can also see more of your page to make design decisions. If you’re using a large monitor, just make sure you design for users with smaller monitors and devices in mind.

A second computer for testing

Many designers and developers find it useful to have a test computer running a different platform than the computer they use for development (i.e., if you design on a Mac, test on a PC). Because browsers work differently on Macs than on Windows machines, it’s critical to test your pages in as many environments as possible, and particularly on the current Windows operating system. If you are a hobbyist web designer working at home, you could check your pages on a friend’s machine. Mac users should check out the “Run Windows on Your Mac” sidebar.

Mobile devices for testing

The web has gone mobile! That means it is absolutely critical that you test the appearance and performance of your site on browsers on smartphones and tablet devices. Device testing is discussed in Chapter 17, Responsive Web Design.

A scanner and/or camera

If you anticipate making your own images and textures, you’ll need some tools for creating them.

Run Windows on Your Mac

Web Production Software

There’s no shortage of software available for creating web pages. In the early days, we just made do with tools originally designed for print. Today, there are wonderful tools created specifically with web design in mind that make the process more efficient. It is a delicate business listing software in a book such as this because a) there are so many programs, b) everyone has their personal favorite, and c) new tools come along so rapidly that there are surely newer, cooler options that you have access to that didn’t exist as I wrote this.

That said, here is a general overview of the types of software that comprise the tools of our trade, along with a few specific mentions of the most popular in each class.

NOTE

To do the exercises in this book, all you’ll need is the text editor that came with your operating system and free image creation software. There is no need to purchase anything to follow along.

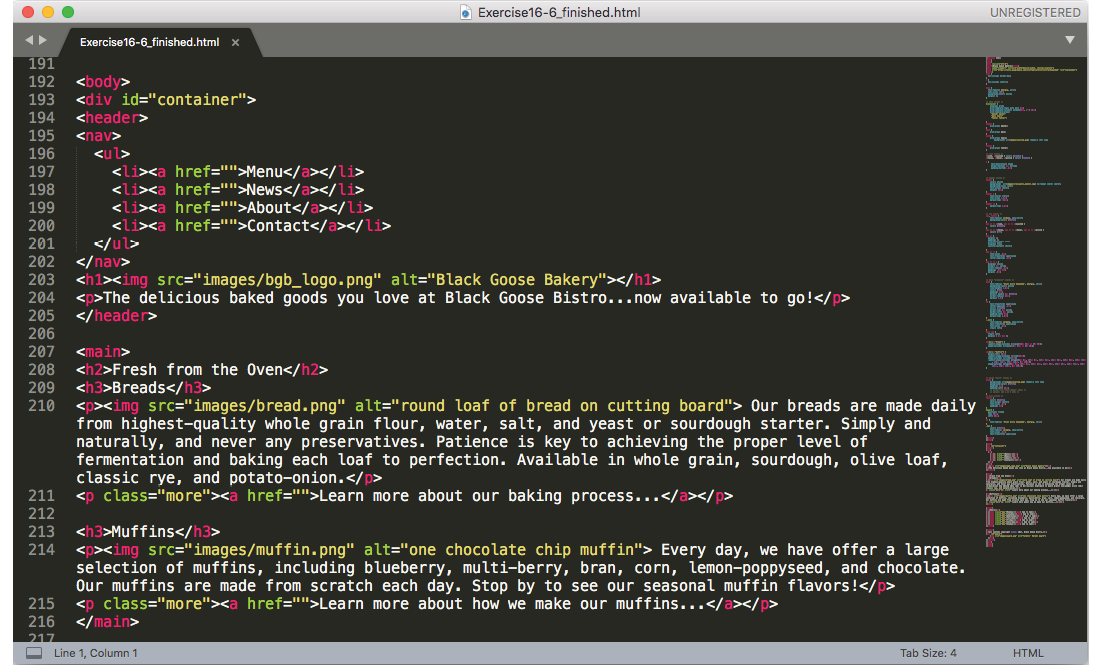

Coding tools

Although you can get by with the simple text editors that come with your computer, a dedicated code editor makes the task of writing HTML, CSS, and JavaScript much easier. Code editors understand the syntax of the code you write, so they can do things for you like color coding, error detection, and automatically finishing simple tasks like closing HTML tags. Some provide page previews so you can view the results of your code as you work.

Figure 1-6 shows how an HTML document looks in the Sublime Text editor. Here are just a few of the better-known code editors for web production that are worth exploring:

- Sublime Text (sublimetext.com)

- Atom (free from GitHub; atom.io)

- Brackets (free from Adobe; brackets.io)

- CodeKit (codekitapp.com; Mac only)

- Adobe Dreamweaver (www.adobe.com/products/dreamweaver.html)

- Coda (panic.com/coda/)

- Microsoft Visual Studio (visualstudio.com)

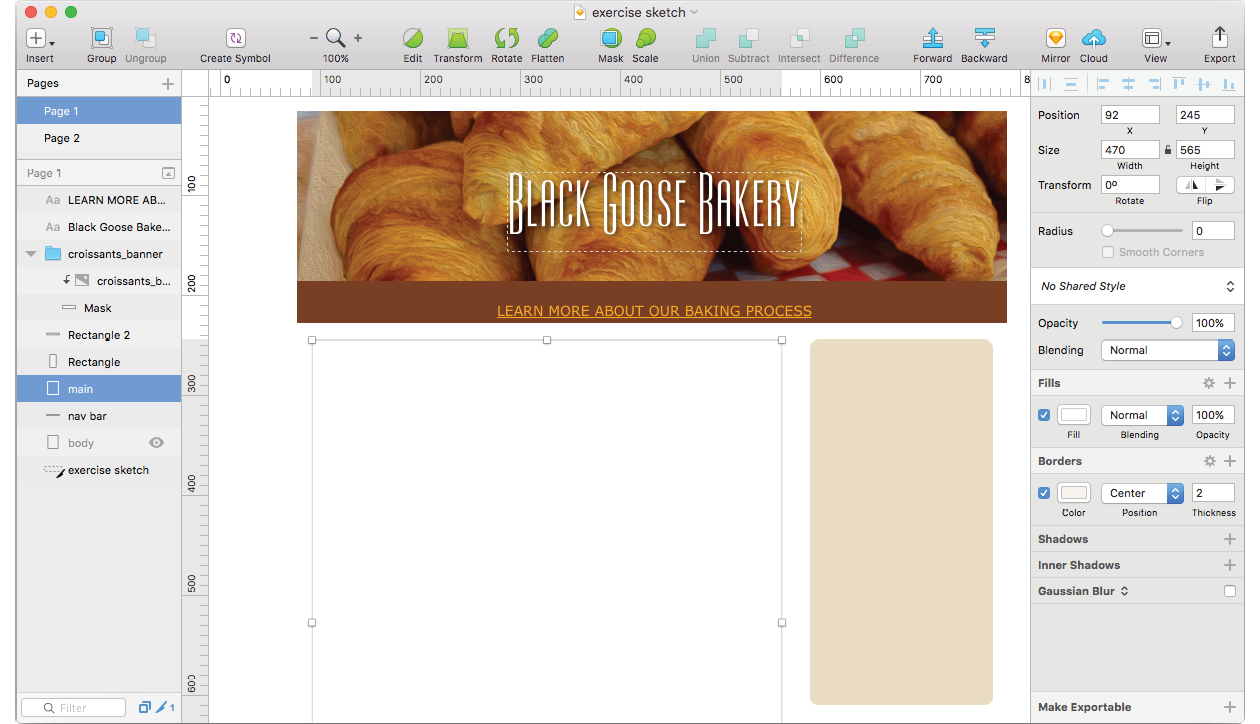

User interface and layout tools

There is a new breed of interface design tools made specifically for websites and other applications. Because they have been designed from scratch with interface design in mind, they seem to anticipate a web designer’s every need. Interface design tools make it easy to design multiple layouts (such as layouts at various screen sizes) as well as export images and code for use in production. Some allow basic interactivity such as clicks and swipes, so your mockups can be shared online and used for basic interface testing.

Sketch (sketchapp.com, Mac only), shown in Figure 1-7, is extremely popular at the time of this writing. Other options include the following:

- Affinity Designer (affinity.serif.com/en-us/designer/)

- Adobe XD (www.adobe.com/products/xd.html)

- Figma (figma.com)

- UXPin (uxpin.com)

Web graphic creation tools

It is certainly possible to create all of the images you need for a site by using one of the interface design tools just listed. There are also programs that focus solely on image creation that can export files in web-appropriate formats. For professional designers, the Adobe Creative Cloud (adobe.com) suite of tools, which includes Photoshop (Figure 1-8), Illustrator, and other high-end design tools, is worth the investment.

If the Adobe monthly subscription fee is out of reach, you can try lower-cost alternatives that provide many of the same features. The number of graphics tools out there is dizzying, so I’m gathering just a few here:

- GIMP (free, open source; gimp.org)

- Corel PaintShop Pro (for photo editing; paintshoppro.com; Windows only)

- Corel Draw (for vector drawing; coreldraw.com; Windows only)

- Pixelmator (pixelmator.com; Mac only)

The following image editors work right in your browser, without the need to download a program, although you do need to pay for an account:

- SumoPaint (sumopaint.com)

- Pixlr (pixlr.com)

A variety of browsers

One of the biggest challenges for web designers is that our sites may look and behave differently from browser to browser. For this reason, it is critical that we test our designs early and often on the widest range of browsers possible. These are the browsers designers and developers keep around for testing:

- Chrome (google.com/chrome)

- Firefox (www.mozilla.org)

- MS Edge (www.microsoft.com/en-us/windows/microsoft-edge; Windows only)

- Internet Explorer 9–11 (www.microsoft.com; search “Internet Explorer”; Windows only)

- Safari (support.apple.com/downloads/#safari; Mac only)

- Opera (opera.com)

You will also need to test on a variety of smartphone browsers including iOS Safari, Android browsers, and third-party mobile browsers. We will discuss mobile testing further in Chapter 17.

File management and transfer tools

Web design and development involves a lot of moving files around, particularly from the computer where you do your work to the server computer that hosts the site. To move files across the internet, you use an FTP (short for File Transfer Protocol) program. You will find that many hosting services offer their own FTP tools for uploading your files to their servers. Many of the code editors listed earlier also include built-in FTP functionality. Or, you can use a standalone FTP program, such as one of these:

- Filezilla (filezilla-project.org; free, all platforms)

- Cyberduck (cyberduck.io; Mac and Windows)

- WinSCP (winscp.net/eng/index.php; free, Windows only)

- Transmit (panic.com/transmit/; Mac only)

You may also find it useful to have a terminal application (command-line tool) that allows you to type Unix commands for setting file permissions, moving or copying files and directories, or managing the server software. Command-line tools, which have a number of uses in web design and development workflow, are discussed in more detail in Chapter 20, Modern Web Development Tools:

- Terminal (installed with macOS; shown in Figure 1-9)

- Cygwin (cygwin.com; Linux emulator for Windows that includes a command-line tool)

What You’ve Learned

I hope that this chapter has given you an overview of the many roles and responsibilities that fall under the umbrella of “web design.” I also hope that you come away realizing that you don’t need to learn everything. And even if you want to learn everything eventually, you don’t need to learn it all at once. So relax, and don’t worry. The other good news is that, while many professional tools exist, it is possible to create a basic website and get it up and running without spending much money by using freely available or inexpensive tools and your existing computer setup.

As you’ll soon see, it’s easy to get started making web pages—you will be able to create simple pages by the time you’re done reading this book. From there, you can continue adding to your bag of tricks and find your particular niche in web design. In the meantime, try answering the questions in Exercise 1-1.

Exercise 1-1. Taking stock

Test Yourself

Each chapter in this book ends with a few questions that you can answer to see if you picked up the important bits of information. Answers appear in Appendix A.

- Match these web professionals with the final product they might be responsible for producing:

a.

Graphic designer

_____

HTML and CSS documents

b.

Production department

_____

PHP scripts

c.

User experience designer

_____

“Look and feel” deliverables

d.

Backend programmer

_____

Storyboards

- What does the W3C do?

- Match the web technology with its appropriate task:

a.

HTML

_____

Checks a form field for a valid entry

b.

CSS

_____

Creates a custom server-side web application

c.

JavaScript

_____

Identifies text as a second-level heading

d.

Ruby

_____

Makes all second-level headings blue

- What is the difference between frontend and backend web development?

- What does an FTP tool do and how do you get one?