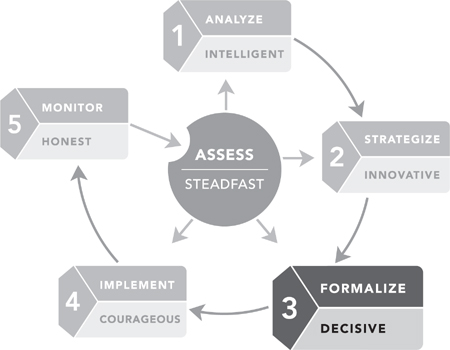

Once the wealth holder or family develops the principles, their implementation can be accomplished by standards and a business plan that allows all of those involved to know the rules, clearly and uniquely set out to support the principles. The standards need to be developed by independent and objective professionals who have the capacity and training to set out the management of each principle. Tools and resources can then be allocated to ensure that select service providers can do their jobs efficiently and effectively. Once the business plan is created, it can be monitored, assessed, and modified over time, and professionals running the family wealth can be evaluated objectively by the wealth holder or others.

In Step 1, we defined the long-term goals and objectives of the wealth holder. We identified the professionals who would be involved in the wealth management process; and we ensured that decision makers were aware of their roles and responsibilities as well as of the standards, regulations, and policies that would impact the investment process.

In Step 2, we gathered the information that would be critical to the development of the wealth management strategy:

R Risk tolerances

A Asset, asset class preferences, activities and attributes of capital

T Time horizon

E Expected outcomes

In Step 3, we’re going to develop the wealth management strategy that:

![]() Represents the greatest probability of achieving the wealth holder’s goals and objectives

Represents the greatest probability of achieving the wealth holder’s goals and objectives

![]() Is consistent with the wealth holder’s unique risk-return profile

Is consistent with the wealth holder’s unique risk-return profile

![]() Is consistent with the Standards Director’s implementation and monitoring constraints

Is consistent with the Standards Director’s implementation and monitoring constraints

Once these requirements are satisfied, the Standards Director has the inputs to prepare the wealth holder’s Private Wealth Policy Statement (PWPS).

Dimension 3.1: Define the strategy that is consistent with RATE

Leadership Behavior: Strategic

Standard

The Standards Director defines in writing the wealth management strategy that is consistent with:

a. Risk tolerances

b. Asset class preferences (taking into consideration the wealth holder’s other assets)

c. Mission-based or philanthropic objectives (if defined in Dimension 1.1)

d. Time horizons

e. Performance objectives

f. Rebalancing guidelines

Strategic design of a portfolio thus starts long before asset allocation. . . . That means at a given time, a portfolio of 90 percent equities can make sense for one person while a portfolio of 10 percent equities can make sense for another. Neither percentage comes from a hard-and-fast rule that should apply to every investor. Each reflects a notion of appropriateness designed for the particular investor.

Once the Standards Director knows the wealth holder’s goals and objectives and has determined the inputs to RATE (Dimensions 2.1–2.4), the Director is ready to define the strategies that produce the greatest probability of achieving the wealth holder’s goals and objectives. Considerable research and experience has shown that the choice of assets (staff, service providers, and money managers) and asset classes, and subsequent allocation of each, will have more impact on the long-term performance of the wealth management strategy than any other factor.

How assets are deployed among various competing objectives requires a thorough knowledge of the following topics:

![]() The assets, their availability and usefulness

The assets, their availability and usefulness

![]() Other available choices and options

Other available choices and options

![]() The risk-reward ratio of deploying (or not deploying) different assets

The risk-reward ratio of deploying (or not deploying) different assets

![]() Redeployment or rebalancing as the market or the portfolio’s situation changes

Redeployment or rebalancing as the market or the portfolio’s situation changes

At this point, it may be worthwhile to comment on the use of optimization (i.e., asset allocation) software when developing an investment strategy. Yes, a Standards Director needs to have access to good asset allocation tools—particularly in determining the allocation between equities, fixed income, and cash. However, due to the great disparity between different software offerings and services provided by investment consultants, we would caution Directors to carefully research the investment expertise of the software developer or the investment consultant. The old adage “garbage in, garbage out” has never been more applicable.

Most asset allocation strategies are driven by three inputs:

![]() The modeled or expected risk (standard deviation of returns) of each asset class

The modeled or expected risk (standard deviation of returns) of each asset class

![]() The modeled or expected return of each asset class

The modeled or expected return of each asset class

![]() The modeled or expected correlations of each asset class’s return with that of the other asset classes

The modeled or expected correlations of each asset class’s return with that of the other asset classes

The Standards Director’s responsibility is to ensure that these expected or modeled inputs are reasonable, which is no easy task. Experience suggests that historical data on different asset classes appears to be quite useful with respect to developing standard deviation estimates, “reasonably useful for correlations, and virtually useless for expected returns” (William Sharpe, Nobel Prize–winning economist). Simple extrapolations of historical data are not only likely to be poor estimates of future performance but also may lead to the development of expectations that cannot be met.

Over the years, we have seen investment decision makers make one or more of the following mistakes when developing an asset allocation strategy:

![]() Believing that asset allocation is a science and accepting a level of precision or confidence that simply is unwarranted. There is still an element of art and uncertainty involved in the development of an appropriate asset strategy. Once the critical allocations have been made between equity, fixed income, and cash, the allocation to additional asset classes can be determined with common sense through an intuitive process. Despite advances in portfolio modeling, not all asset allocation decisions have been reduced to a computerized solution.

Believing that asset allocation is a science and accepting a level of precision or confidence that simply is unwarranted. There is still an element of art and uncertainty involved in the development of an appropriate asset strategy. Once the critical allocations have been made between equity, fixed income, and cash, the allocation to additional asset classes can be determined with common sense through an intuitive process. Despite advances in portfolio modeling, not all asset allocation decisions have been reduced to a computerized solution.

![]() Not informing the wealth holder of how the asset allocation helps accomplish what the wealth is for. If the wealth holder does not fully understand the strategy, it is likely he or she will want to bolt at the first sign of market volatility.

Not informing the wealth holder of how the asset allocation helps accomplish what the wealth is for. If the wealth holder does not fully understand the strategy, it is likely he or she will want to bolt at the first sign of market volatility.

![]() Underallocating. Making an allocation of less than 5 percent rarely makes good sense for two reasons: (1) it probably will not materially change the risk-return profile of the wealth holder’s portfolio, and (2) it will be costly, in terms of both implementation and monitoring.

Underallocating. Making an allocation of less than 5 percent rarely makes good sense for two reasons: (1) it probably will not materially change the risk-return profile of the wealth holder’s portfolio, and (2) it will be costly, in terms of both implementation and monitoring.

![]() Making an allocation to an asset that the Standards Director cannot properly implement or monitor (discussed further in Dimension 3.2). The classic example is an allocation to hedge funds. Because of the lack of transparency and the complexity of the financial instruments employed, the Director may not be able to employ the same level of due diligence as could be applied to a traditional money manager. If the Standards Director lacks the time, inclination, or knowledge to conduct appropriate due diligence—be it of an asset class or an investment manager—he or she should stay clear of the strategy or the manager.

Making an allocation to an asset that the Standards Director cannot properly implement or monitor (discussed further in Dimension 3.2). The classic example is an allocation to hedge funds. Because of the lack of transparency and the complexity of the financial instruments employed, the Director may not be able to employ the same level of due diligence as could be applied to a traditional money manager. If the Standards Director lacks the time, inclination, or knowledge to conduct appropriate due diligence—be it of an asset class or an investment manager—he or she should stay clear of the strategy or the manager.

Dimension 3.2: Ensure the strategy is consistent with implementation and monitoring constraints

Leadership Behavior: Pragmatic

Standard

The Standards Director ensures that the asset allocation and investment strategy are consistent with the Standards Director’s implementation and monitoring constraints.

If wealth is about freedom, convoluted investment strategies are rarely strategic. There can be no process, little delegatable, and no likelihood that the wealth holder will fully understand what he or she is investing in. The complexity alone can deprive family members of feelings of freedom. Instead they spend time trying to understand what they cannot and feeling unsure whether they should trust those running the investments. How can a person pursue passions to self-actualization if he or she is busy in a maze of derivatives and jargon?

What starts out as strategy must be translated into reality with implementation, and what is implemented needs to be monitored. The proposed wealth management strategy (Dimension 3.1) now must be carefully evaluated to determine whether the suggested strategy can be prudently implemented (discussed in more detail in Dimension 4.1) and then effectively and efficiently monitored (discussed in more detail in Dimension 5.1) on an ongoing basis.

One demonstrates prudence by the process through which one manages wealth management decisions. No strategy is imprudent on its face. It is the way in which it is used, and the way decisions regarding its use are made, that will be examined to determine whether the prudence test has been met. Even the most aggressive and unconventional strategy can meet the standard if arrived at through a sound process, while the most conservative and traditional one may not measure up if a sound process is lacking.

The greatest risk in the development of any strategy is omission—leaving out something vital. This is why standards and a defined decision-making process, such as the one provided in this book, are so critical.

At this point, the Standards Director should be able to demonstrate that he or she has documented the following inputs that are going to be used to develop the wealth management strategy:

![]() The current and projected resources and obligations of the wealth holder

The current and projected resources and obligations of the wealth holder

![]() The rationale for the choice of performance goals, time horizons, and permissible asset classes and the sensitivity to variations in each

The rationale for the choice of performance goals, time horizons, and permissible asset classes and the sensitivity to variations in each

![]() The basis for the validity of the capital markets data utilized in determining the asset allocation

The basis for the validity of the capital markets data utilized in determining the asset allocation

In his book on Winston Churchill, Churchill on Leadership, Steven Hayward outlines several rules for effective decision making that Churchill followed:

Always keep the central or most important aspect of the current problem in mind, know how to balance the chances [risk] on both sides of a decision, and keep these factors in proportion; and remain open to changing your mind in the presence of new facts.

Don’t try to look too far ahead, try for excessive perfection, or make decisions for decision’s sake that would better be postponed or not made at all.

Churchill’s philosophy in managing important decisions also applies to wealth management. Every decision comes with a certain amount of risk, and not every decision will yield a perfect outcome. Success is achieved by seeking out the realistic balance between risk and reward.

Dimension 3.3: Formalize the strategy in detail and communicate

Leadership Behavior: Communicative

Standard

The Standards Director ensures that, for each entity and individual, there is defined in writing a Private Wealth Policy Statement (PWPS).

A family should design its investment policies, processes, and disciplines strategically to meet the family’s goals and objectives. The challenge again is achieving the perspective necessary to see the destination before selecting the route to get there. Every element of investment theory, policy, and analytics should work together to make the wealth do what it is intended to do by helping the wealth holder accomplish his or her purposes.

In our opinion, the preparation and ongoing maintenance of the wealth holder’s Private Wealth Policy Statement (PWPS) is the most important function performed by the Standards Director. So critical is this role, we have prepared a sample PWPS template (see Appendix) based on the Ethos framework.

The PWPS should be viewed as the business plan and the essential management tool for directing and communicating the activities of the wealth management strategy. It should be a formal, long-range, strategic plan that allows the Standards Director to coordinate the management of the strategy within a logical and consistent framework. All material facts, assumptions, and opinions should be included. Although we seem to focus on the investment strategy, the Standards Director can use the guidance here relating to investment strategy as a road map to consideration of every strategy to be used. Similar treatment must be implemented as business planning for philanthropic programs, for capitalization guidelines, for governance, for family values and legacy communication, and for education. All of these aspects of the family wealth program must be considered in the PWPS.

The Standards Director needs to develop the PWPS with the understanding that it will be implemented in a complex and dynamic environment. The PWPS will produce the greatest benefits during periods of adverse conditions, acting as a stabilizer for decision makers who otherwise would be tempted to alter the sound strategy because of irrational fears. Its mere existence will cause decision makers to pause and consider the external and internal circumstances that prompted the development of the PWPS in the first place. This is what the substance of good policy development is all about: the framework and process that will allow cooler heads and a longer-term outlook to prevail.

In periods of financial market prosperity, almost any investment program, no matter how ad hoc its strategy, will likely generate impressive results. In those circumstances, the advantages of a comprehensive PWPS and the time devoted to its development may appear to be marginal. However, even under favorable market conditions, the PWPS may reduce the temptation to increase the aggressiveness of an investment program as other decision makers attempt to extrapolate positive current market trends into the future.

There are a number of reasons why the PWPS is so critical:

![]() The PWPS provides logical guidance during periods of uncertainty.

The PWPS provides logical guidance during periods of uncertainty.

![]() The PWPS provides a paper trail of polices, practices, and procedures that can serve as critical evidence used in the defenses against accusations of imprudence or mismanagement.

The PWPS provides a paper trail of polices, practices, and procedures that can serve as critical evidence used in the defenses against accusations of imprudence or mismanagement.

![]() The PWPS provides a baseline from which to monitor performance of overall strategies, as well as the performance of the Standards Director.

The PWPS provides a baseline from which to monitor performance of overall strategies, as well as the performance of the Standards Director.

![]() For estate planning purposes, the PWPS should be included and coordinated with other estate planning documents, providing less sophisticated heirs and executors appropriate guidance for continuing the prudent management of the wealth management strategy.

For estate planning purposes, the PWPS should be included and coordinated with other estate planning documents, providing less sophisticated heirs and executors appropriate guidance for continuing the prudent management of the wealth management strategy.

The PWPS should combine elements of planning and philosophy and should address all five steps of the Ethos process. The sample PWPS included in the Appendix has the following main sections and subheadings (note that the PWPS follows the same structure as the Ethos decision-making framework):

Section I: Definitions

Section II: Purpose

Section III: Statement of Principles

Section IV: Duties and Responsibilities

Section V: Ethics Statement

Section VI: Persons Serving in a Fiduciary Capacity

Section VII: Inputs Used to Develop the Wealth Management Strategy

Section VIII: Money Manager and Custodian

Section IX: Monitoring Procedures

Section X: Review of the PWPS

Others may be required depending on the wealth holder or the family. Use this framework as a starting point.