Building strategies and following processes, executing the vision of what wealth is for, requires expertise that many wealth holders do not have as well as considerable time and attention that many wealth holders do not want to devote. The management of significant family wealth, like any worthwhile enterprise, requires standards to govern operations, to measure performance, to ensure proper process, and ultimately to avoid disasters like Madoff, Stanford, and others. A wealth holder wanting to live life free from the burdens of wealth will want to delegate the management of wealth but will require accountability and measurement tools to ensure that the wealth is being managed appropriately.

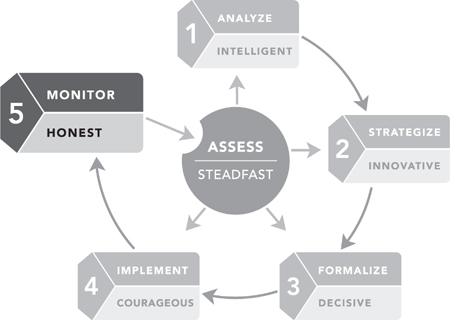

Once the optimal wealth management strategy has been designed, the PWPS prepared, and the strategy implemented, the final critical step is the ongoing monitoring and assessment of the wealth management program. Monitoring the resulting performance of selected service providers and evaluating the continuing viability of the wealth holder’s goals and objectives constitutes the next-to-final step of the wealth management process.

The monitoring function extends beyond a strict examination of performance: by definition, monitoring occurs across all policy and procedural issues. Monitoring includes an analysis of not only what happened but also why.

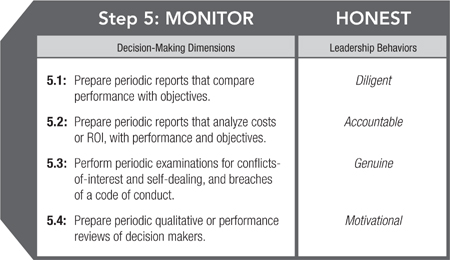

Dimension 5.1: Prepare periodic reports that compare performance with objectives

Leadership Behavior: Diligent

Standard

The Standards Director defines a process to periodically monitor the wealth management strategy to ensure that it is meeting defined goals and objectives.

The board of a well-run company always has its expectations for job performance articulated and its review procedures well developed. Worldwide, family office executives bemoan the fact that their “constituents” do not appreciate how well they do their jobs. Of course, some constituents actually do understand the efforts and skill it takes but not all. And more than one family office executive has taken advantage of his or her position to defraud the family.

The preparation and maintenance of the PWPS is the most critical function the Standards Director performs. The second most critical function is monitoring. This is the step where the Standards Director will likely make the most mistakes and, even when executed properly, will be the costliest component of the wealth management program—in terms of time, the staff required, and the technology to be employed.

When done properly, monitoring triggers a number of periodic reviews:

![]() Monthly: At least monthly, the Standards Director should analyze custodial statements. He or she should pay particular attention to transactions initiated by separate account managers: (1) Are the trades consistent with the manager’s stated strategy, and (2) is there evidence that the manager is seeking best price and execution (Dimension 5.2)?

Monthly: At least monthly, the Standards Director should analyze custodial statements. He or she should pay particular attention to transactions initiated by separate account managers: (1) Are the trades consistent with the manager’s stated strategy, and (2) is there evidence that the manager is seeking best price and execution (Dimension 5.2)?

![]() Quarterly: At least quarterly, the Standards Director should compare:

Quarterly: At least quarterly, the Standards Director should compare:

![]() The wealth holder’s actual asset allocation to the strategic asset allocation defined in the PWPS to determine whether the portfolio should be rebalanced back to the strategic asset allocation (Dimension 3.1). The discipline of rebalancing, in essence, controls risk and forces the wealth strategy to move along a predetermined path. Rebalancing limits should be set so they do not trigger continuous readjustment to the portfolio—we have found that a collar of plus or minus 5 percent around the strategic asset allocation works fine.

The wealth holder’s actual asset allocation to the strategic asset allocation defined in the PWPS to determine whether the portfolio should be rebalanced back to the strategic asset allocation (Dimension 3.1). The discipline of rebalancing, in essence, controls risk and forces the wealth strategy to move along a predetermined path. Rebalancing limits should be set so they do not trigger continuous readjustment to the portfolio—we have found that a collar of plus or minus 5 percent around the strategic asset allocation works fine.

![]() Money manager performance against benchmarks established in the PWPS, including a comparison of each manager’s performance against an appropriate index and peer group.

Money manager performance against benchmarks established in the PWPS, including a comparison of each manager’s performance against an appropriate index and peer group.

![]() Annually: At least annually, there should be a formal review of the PWPS to determine whether the wealth holder’s goals and objectives have changed and whether the wealth management strategy still holds the highest probability of meeting stated goals and objectives.

Annually: At least annually, there should be a formal review of the PWPS to determine whether the wealth holder’s goals and objectives have changed and whether the wealth management strategy still holds the highest probability of meeting stated goals and objectives.

Central to the monitoring function is performance attribution analysis, which consists of two overlapping and sequential procedures: (1) performance measurement, the science; and (2) performance evaluation, the art.

Performance measurement consists of calculating portfolio statistics (standard deviation; Alpha, Sharpe, and Sortino ratios) and rates of return. Although performance measurement is referred to as the “science,” it is far from being exact.

The source and handling of the data used in performance measurement may have an impact on calculations. For this reason, the Standards Director should request performance information from different sources to try to catch potential errors. For example, the rate of return calculated by the custodian may differ from the rate of return reported by a money manager, and both of these returns may yet be different from the rate of return the Director calculates using the Director’s own performance measurement software. Like navigating a ship at sea, the prudent sailor takes as many bearings as possible to try to triangulate an exact fix.

Performance evaluation is where the skills of the Standards Director come into play: other decision makers will be looking to the Director to identify the appropriate call to action. It is this phase of the analysis where the Director compares the results of performance measurement to the portfolio’s PWPS and, if needed, suggest appropriate action to bring the wealth management strategy back into alignment.

![]() What is the current asset allocation of the overall portfolio?

What is the current asset allocation of the overall portfolio?

![]() Does it need to be rebalanced? If so, what are the cash flows for the coming six months, and can these cash flows (contributions or disbursements) be used to rebalance the portfolio?

Does it need to be rebalanced? If so, what are the cash flows for the coming six months, and can these cash flows (contributions or disbursements) be used to rebalance the portfolio?

![]() How has each money manager performed relative to their indices and peer groups? Is there evidence that a money manager may be deviating from the stated strategy?

How has each money manager performed relative to their indices and peer groups? Is there evidence that a money manager may be deviating from the stated strategy?

![]() Are there managers that should be placed on a watch list or even terminated?

Are there managers that should be placed on a watch list or even terminated?

The decision to terminate a manager should not be taken lightly, since there are a number of costs associated with changing managers. When poor performance becomes an issue, it is important that the Standards Director approach the evaluation process with the same rigor he or she applied when conducting due diligence on the money manager. In fact, we suggest it is prudent to apply the same due diligence criteria that the Director used in the search phase (Step 4):

![]() Has there been a change to the portfolio team?

Has there been a change to the portfolio team?

![]() Has the money manager encountered legal or regulatory problems?

Has the money manager encountered legal or regulatory problems?

![]() Has there been a change in the money manager’s strategy?

Has there been a change in the money manager’s strategy?

![]() Has there been a change in the asset allocation structure of the money manager’s portfolio (for example, is the manager beginning to hold more cash)?

Has there been a change in the asset allocation structure of the money manager’s portfolio (for example, is the manager beginning to hold more cash)?

![]() Has there been a marked increase in portfolio turnover?

Has there been a marked increase in portfolio turnover?

![]() Has the money manager consistently performed below the returns of an appropriate index or below the manager’s peer group?

Has the money manager consistently performed below the returns of an appropriate index or below the manager’s peer group?

![]() Has risk-adjusted performance (Alpha, Sharpe, and Sortino ratios) dropped below the performance of an appropriate index or below the money manager’s peer group?

Has risk-adjusted performance (Alpha, Sharpe, and Sortino ratios) dropped below the performance of an appropriate index or below the money manager’s peer group?

Over the years, we have seen a lot of wealth managers try to quantify when a money manager should be terminated—for example, a certain number of quarters below a benchmark. We think a disciplined methodology is essential; however, the best approach is remarkably simple: Fire the manager when you have lost confidence in his or her ability to do the job.

What we say here for money managers is just as true for other advisors and employees. If expectations are clearly articulated by the Standards Director, the performance of every accountant, every lawyer, every advisor, and every employee must be evaluated regularly in terms of those expectations. Any should be fired when you lose confidence in his or her ability to do that job.

Dimension 5.2: Prepare periodic reports that analyze costs, or return on investment, with performance and objectives

Leadership Behavior: Accountable

Standard

The Standards Director periodically analyzes all fees and expenses associated with the wealth management strategy, including:

a. Fees paid to money managers, custodians, and investment consultants

b. Brokerage costs and use of soft dollars

c. Fees and expenses of service providers

Measuring costs requires identifying what is paid to the provider but also what is paid or lost to poor advice. The fee paid the most expensive estate planner for the most sophisticated family limited partnership pales beside the loss in value and freedom suffered when that partnership is imposed on the dysfunctional family and becomes cannon fodder for their pitched battles.

No matter what the business, decision makers have a responsibility to control and account for expenses. The Standards Director’s role is no exception.

Wealth management costs and expenses can be broken down into four broad categories. Certain expenses can be obscured or moved from one category to another to create apparent savings, so Standards Directors are cautioned to consider costs across all four categories.

![]() Advisor fees, employee salaries, and money manager fees and expenses: These comparisons should be made by peer group or investment strategy. For example, the Standards Director should not compare the fees of a large-cap manager to those of a small-cap manager. The Director also should watch the fees being paid for alternative investment strategies: The differences between traditional money management and hedge fund strategies have begun to blur, yet the costs associated with hedge funds are considerably higher. Why pay many times more for an investment strategy that is largely accomplished by a traditional money manager with lower fees and expenses?

Advisor fees, employee salaries, and money manager fees and expenses: These comparisons should be made by peer group or investment strategy. For example, the Standards Director should not compare the fees of a large-cap manager to those of a small-cap manager. The Director also should watch the fees being paid for alternative investment strategies: The differences between traditional money management and hedge fund strategies have begun to blur, yet the costs associated with hedge funds are considerably higher. Why pay many times more for an investment strategy that is largely accomplished by a traditional money manager with lower fees and expenses?

![]() Trading costs for separately managed portfolios, including commission charges (soft dollars) and execution expenses (best execution): This large and important component of cost control is often overlooked and can be the subject of abuse if not carefully monitored. A simple check the Standards Director can employ is to analyze the custodial statement and see which brokerage firms are being used by the separate account manager to trade the portfolio’s account. (If that level of detail is not being provided by the custodian, the Director may want to consider changing custodians or request the trading information directly from the money manager.) Ideally, the Director wants to see that the money manager is using a host of different brokerage firms for executing the trades and that commission charges are in the institutional range (in the United States, 4 to 8 cents per share). If that is not evident, a call to the money manager is warranted for an explanation.

Trading costs for separately managed portfolios, including commission charges (soft dollars) and execution expenses (best execution): This large and important component of cost control is often overlooked and can be the subject of abuse if not carefully monitored. A simple check the Standards Director can employ is to analyze the custodial statement and see which brokerage firms are being used by the separate account manager to trade the portfolio’s account. (If that level of detail is not being provided by the custodian, the Director may want to consider changing custodians or request the trading information directly from the money manager.) Ideally, the Director wants to see that the money manager is using a host of different brokerage firms for executing the trades and that commission charges are in the institutional range (in the United States, 4 to 8 cents per share). If that is not evident, a call to the money manager is warranted for an explanation.

![]() Custodial charges, including custodial fees, transaction charges, and cash management fees: As noted in Dimension 4.1, the Standards Director should check the expense ratio of the money market fund being used by the custodian to ensure that the cash accounts are invested in an institutional money market.

Custodial charges, including custodial fees, transaction charges, and cash management fees: As noted in Dimension 4.1, the Standards Director should check the expense ratio of the money market fund being used by the custodian to ensure that the cash accounts are invested in an institutional money market.

![]() Consulting, recordkeeping, or administrative costs and fees: Particular attention should be paid to determine whether there are revenue-sharing or finder’s fee arrangements between service providers. If such fees exist, they should be applied to the benefit of the wealth holder.

Consulting, recordkeeping, or administrative costs and fees: Particular attention should be paid to determine whether there are revenue-sharing or finder’s fee arrangements between service providers. If such fees exist, they should be applied to the benefit of the wealth holder.

The Standards Director has the responsibility to identify every party that has been compensated from the wealth holder’s portfolio and demonstrate that the compensation received by every money manager and service provider was fair and reasonable for the level of services being provided.

The Standards Director is also accountable for ensuring that each provider has what is needed to perform services well and efficiently.

Dimension 5.3: Conduct periodic examinations for conflicts of interest, self-dealing, and breaches of a code of conduct

Leadership Behavior: Genuine

Standard

The Standards Director periodically reviews compensation agreements and service agreements of service providers to ensure that they do not contain provisions that:

a. Conflict with the wealth holder’s goals and objectives

b. Are performance-based using short- to intermediate-term (less than five years) investment results

The Standards Director also defines in writing an ethics statement and periodically checks for conflicts of interest. The ethics statement requires all persons involved with managing wealth to:

a. Annually acknowledge the ethics statement

b. Disclose all conflicts of interest as they become known

Distrust and fear are impediments to comfort. Lack of control or understanding can create anxiety and discomfort. What you do not know or understand makes you uncomfortable because it is hard to relax in the presence of uncertainty and threats unseen.

The most common mistake made by service providers is the omission of one or more prudent practices, as opposed to the commission of a prohibited act or being involved in a conflict of interest. However, instances of the latter are common enough that the Standards Director should monitor the wealth management program for possible problems. Any activity that is not in the best interest of the wealth holder will cause problems, and it is critical that the Director ensure that no party has been unduly enriched by the wealth holder’s assets.

Paraphrasing Stephen M. R. Covey from his bestseller, The Speed of Trust, “trust” has become the global currency for the wealth management industry. Trust has to be the basis for every relationship the wealth holder has with service providers, particularly the relationship with the Standards Director. It is the Standards Director who is responsible for setting the tone at the top; the ethical standards defined and exhibited by the Director cannot be underestimated. The behavior of the wealth management team oftentimes will mirror the standards of integrity and fair dealing (i.e., avoidance of conflicts of interests and self-entitlements) exhibited by the Director.

With trust comes the duty of loyalty; no one involved in managing the wealth holder’s assets should invest or manage portfolio assets in such a way that there arises even a hint of a personal conflict of interest. Decision makers have a duty to employ an objective, independent due diligence process at all times and have defined policies and procedures to manage potential conflicts of interests.

A code of conduct, by definition, is rules-based. In contrast, a code of ethics is principles-based; at least, it should be. Unfortunately, most of the ethical codes we see written for the wealth management industry are rules-based and compliance-driven; therefore, they should be labeled codes of conduct.

The distinction is important because rules-based conduct rarely succeeds over the long term. Rules rarely elicit as high a level of behavior as principles: rules require little discernment, whereas principles require a full engagement of the head and the heart.

When drafting or reviewing codes of conduct or ethical codes, the Standards Director should remember that rules often weaken original intent. Principles require more work—in drafting and in explaining to those affected—but, in the long term, principles will have a more positive impact on the wealth management program.

Some money managers and family office staff prefer performance-based fee arrangements. Under these terms, the money manager or staff member receives a higher compensation if he or she is able to exceed a predetermined performance benchmark over a specified period. The argument for these arrangements is that it puts the money manager and staff member on the same side of the table as the wealth holder: If I make more money for the wealth holder, I should make more money.

Unfortunately, it has been demonstrated time and again that such arrangements may not be in the wealth holder’s best interest. If performance is lagging the predetermined benchmark, there is a tendency for decision makers to “double-down,” or increase the level of portfolio risk, in order to make up for lagging performance. Often, the portfolio becomes highly concentrated in “sure bets,” leaving the wealth holder undiversified. If performance-based fees are to be permitted, the risks associated with such fees should be mitigated by extending the specified performance period to five years or more. This way decision makers are still incentivized to manage assets with a long-term perspective.

Hourly fees must be considered carefully as they can incentivize inefficiency by rewarding the provider if the work takes a long time and employs many people. What is more valuable, having your work done well and promptly or well and slowly and inefficiently?

Dimension 5.4: Prepare periodic qualitative reviews or performance reviews of decision makers

Leadership Behavior: Motivational

Standard

The Standards Director prepares periodic qualitative reviews of money managers and service providers.

What is wealth for? We find universal and global agreement that it is not to cause unhappiness. It is not to create fiduciary burdens. It is not to enslave in governance structures. It is not to be weighed down with responsibilities. Freedom from wealth, getting on with life, self-actualization—all have to be possible in whatever design is created to make the wealth do what it is for. Gaining freedom from the burdens of wealth requires wisdom and process—wisdom to allow perspective and process to allow delegation of the minutiae. Together those can provide comfort to lead life free of the burdens of wealth.

The Standards Director’s review of a service provider needs to extend beyond an examination of the provider’s past performance.

Providers of services to private wealth holders are organic, constantly evolving, and subject to the same challenges that every other organization faces—managing people. Disturbances in the workplace will eventually be reflected in performance. Conversely, as we witnessed with certain firms caught up in the U.S. mutual fund scandals of 2003, a decline in investment performance may lure senior investment professionals to compromise principles and permit practices that conflict with the best interests of their portfolios.

Even money management firms that state that they rely on a quantitative model (black box) still need professionals to interpret and implement the output. For this reason, the Standards Director needs to periodically assess the qualitative factors of hired money managers. Although not true in every case, or every geographic locale, there are some general observations we can make about the qualitative factors that affect the wealth management industry:

![]() Ownership: Decision makers who are owners of their firms tend to outperform those who are employees.

Ownership: Decision makers who are owners of their firms tend to outperform those who are employees.

![]() Size of the firm: Smaller organizations tend to be more focused and concentrated in one style. As a result, performance tends to be more volatile—they bounce between the top of the performance universe and sometimes the bottom.

Size of the firm: Smaller organizations tend to be more focused and concentrated in one style. As a result, performance tends to be more volatile—they bounce between the top of the performance universe and sometimes the bottom.

![]() Assets under management: This is a close corollary to the size of the firm. The Standards Director should ensure that the firm can properly invest the dollars being placed, which will vary depending on the asset class. The manager fulfilling a large-cap equity assignment can effectively manage larger amounts than a small-cap manager.

Assets under management: This is a close corollary to the size of the firm. The Standards Director should ensure that the firm can properly invest the dollars being placed, which will vary depending on the asset class. The manager fulfilling a large-cap equity assignment can effectively manage larger amounts than a small-cap manager.

![]() Change in personnel: When there has been a change in personnel, or when a decision maker has left one firm to join another, prudence dictates that the firm be placed on hold until sufficient time (e.g., two years) has passed in order to determine the impact the change may have on performance.

Change in personnel: When there has been a change in personnel, or when a decision maker has left one firm to join another, prudence dictates that the firm be placed on hold until sufficient time (e.g., two years) has passed in order to determine the impact the change may have on performance.

![]() Trading capability: Execution costs have a great impact on performance (Dimension 5.2). The Standards Director should inquire about the firm’s in-house trading capability, as well as how the firm ensures the portfolio is receiving favorable or best execution of trades.

Trading capability: Execution costs have a great impact on performance (Dimension 5.2). The Standards Director should inquire about the firm’s in-house trading capability, as well as how the firm ensures the portfolio is receiving favorable or best execution of trades.

![]() Research: The research analysts often are the unsung heroes: they’re the ones reading the fine print of annual reports and bond indentures to find the gold nuggets for the portfolio managers. How a firm treats, and values, its research analysts will say a lot about the firm. The Standards Director asking the simple question “what percentage of your research is purchased from the street?” will give the Director a good insight into the qualitative decision-making process of the firm. A firm that is relying heavily on research bought from the “street” (that is, from third-party vendors) is going to have difficulty outperforming other managers who are looking at the same data.

Research: The research analysts often are the unsung heroes: they’re the ones reading the fine print of annual reports and bond indentures to find the gold nuggets for the portfolio managers. How a firm treats, and values, its research analysts will say a lot about the firm. The Standards Director asking the simple question “what percentage of your research is purchased from the street?” will give the Director a good insight into the qualitative decision-making process of the firm. A firm that is relying heavily on research bought from the “street” (that is, from third-party vendors) is going to have difficulty outperforming other managers who are looking at the same data.

![]() Soft dollars: Managers who purchase “street” research usually pay for the information from commissions generated from portfolio transactions. Under such a scenario, the Standards Director should understand that part of the manager’s costs for running the organization is paid for by transactions generated from the wealth holder’s portfolio.

Soft dollars: Managers who purchase “street” research usually pay for the information from commissions generated from portfolio transactions. Under such a scenario, the Standards Director should understand that part of the manager’s costs for running the organization is paid for by transactions generated from the wealth holder’s portfolio.

![]() Conflicts policies: The conflicts policies of lawyers, accountants, advisors, and money managers should be studied, and the Standards Director should understand exactly what they are and how they apply to the wealth holder’s situation.

Conflicts policies: The conflicts policies of lawyers, accountants, advisors, and money managers should be studied, and the Standards Director should understand exactly what they are and how they apply to the wealth holder’s situation.