Chapter 3

Evidence Management

Abstract

The lifetime of digital evidence requires that it can be managed and administered throughout every stage of an investigation. This requires that digital evidence is properly collected, handled correctly, and accurately stored to preserve its integrity throughout its lifetime.

Keywords

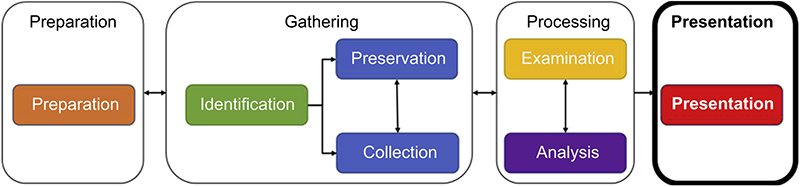

Education; Evidence; Lab; Operations; Policies; RulesThis chapter follows the high-level digital forensic process model to identify the requirements for properly gathering, processing, and handling digital evidence throughout its lifetime. You will learn about the technical, administrative, and physical controls necessary to safeguard digital evidence in before, during, and after a digital forensic investigation.

Introduction

Evidence is a critical component of every digital forensic investigation. Whether it is physical or digital, the methodologies and techniques used to gather, process, and handle evidence ultimately affect its meaningfulness, relevancy, and admissibility. Appropriate safeguards must be present during all investigative work to provide an acceptable level of assurance that the life cycle of evidence is forensically sound1.

Following the high-level digital forensic process model outlined in chapter “Investigative Process Models,” each phase of the investigative workflow will be examined to determine and establish the requirements for managing evidence through its lifetime.

Similar to how the CIA triad (confidentiality, integrity, and availability) outlines the most critical components for implementing information security program; the APT triad (administrative, physical, and technical) describes the most critical components for implementing information security controls in support of digital forensic investigations.

Evidence Rules

Rules of evidence govern when, how, and for what purpose, proof of a legal case may be placed before a trier of fact for consideration. Traditionally, the legal system interpreted digital data as hearsay evidence2 because the contents of this data cannot be proven, beyond a reasonable doubt, to be true. In some jurisdictions, such as under the United States (U.S.) Federal Rules of Evidence 803(6), exceptions to the rule of hearsay evidence exist where digital data is admissible in court if it demonstrates “records of regularly conducted activity” as a business record; such as an act, event, condition, opinion, or diagnosis.

Qualifying business records under this exception requires that the electronically stored information (ESI) can be demonstrated as authentic, reliable, and trustworthy. As described in U.S. Federal Rules of Evidence 803(6), the requirements for qualifying business record are achieved by proving:

1. the record was made at or near the time by—or information was transmitted by—someone with knowledge3;

2. the record was kept in the course of a regularly conducted activity of a business, organization, occupation, or calling, whether or not for profit;

3. making the record was a regular practice of that activity;

4. all these conditions are shown by the testimony of the custodian or another qualified witness, or by a certification that complies with Rule 902(11) or (12) or with a statute permitting certification; and

5. neither the source of information nor the method or circumstances of preparation indicate a lack of trustworthiness.

As described in the U.S. Federal Rules of Evidence 902(11), the requirements for certifying domestic records of regularly conducted activity are achieved by:

1. The original or a copy of a domestic record that meets the requirements of Rule 803(6)(A)-(C) as shown by a certification of the custodian or another qualified person that must be signed in a manner that, if falsely made, would subject the signer to criminal penalty under the laws where the certification was signed. Before the trial or hearing, the proponent must give an adverse party reasonable written notice of the intent to offer the record—and must make the record and certification available for inspection—so that the party has a fair opportunity to challenge them.

As described in the U.S. Federal Rules of Evidence 902(12), the requirements for certifying foreign records of regularly conducted activity are achieved by:

2. The original or a copy of a foreign record that meets the requirements of Rule 803(6)(A)-(C) as shown by a certification of the custodian or another qualified person that must be signed in a manner that, if falsely made, would subject the signer to criminal penalty under the laws where the certification was signed. Before the trial or hearing, the proponent must give an adverse party reasonable written notice of the intent to offer the record—and must make the record and certification available for inspection—so that the party has a fair opportunity to challenge them.

Criteria for what type of data constitutes an admissible business record fall within one of the following categories:

• Technology-generated data is information that has been created and is being maintained as a result of programmatic processes or algorithms (eg, log files). This type of data can fall within the rules of hearsay exception only when the data is proven to be authentic as a result of properly functioning programmatic processes or algorithms.

• Technology-stored data is information that has been created and is being maintained as a result of user input and interactions (eg, word processor document). This type of data can fall within the rules of hearsay exception only when the individual creating the data is reliable, trustworthy, and has not altered the data it any way.

Business records are commonly challenged on issues of whether data was altered or damaged after its creation (integrity) and the validation and verification of the programmatic processes used (authenticity). As a means of lessening these challenges, Federal Rules of Evidence 1002 describes the need for proving the trustworthiness of digital evidence through the production of the original document. To meet this requirement, organizations must implement a series of safeguards, precautions, and controls to ensure that when digital evidence is admitted into a court of law it can be demonstrably proven as authentic against its original source.

Preparation

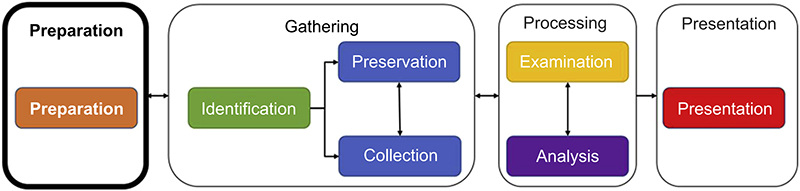

As the first phase of the investigative workflow, preparation is essential for the activities and steps performed in all other phases of the workflow. Ultimately, if the preparation activities and steps are deficient in any way, whether they are not comprehensive enough or not reviewed regularly for accurateness, there is a greater risk that evidence may be interfered with, altered in some form, or even unavailable when needed (Figure 3.1).

Information Security Management

The establishment of information security management is a must so that the organization has defined its overall goals. Management, with involvement from key stakeholders such as legal, privacy, security, and human resources, works to define a series of documents that describe exactly how the organization will go about achieving these goals. Figure 3.2 illustrates the hierarchy of the information security management framework and the relationship between these documents in terms of which have direct influence and precedence over others.

In the context of digital forensics, the implementation of these documents serves as the administrative groundwork for indirectly supporting the subsequent phases where digital evidence is involved. The sections to follow explore these documents individually and provide specifics on the types that contribute to digital forensic readiness.

Policies

At the highest level of documentation, policies are created as formalized blueprint used to describe the organizations goals. These documents address general terms and are not intended to contain the level of detail that are found in standards, guidelines, procedures, or processes. Before writing a policy document, the first step is to define the scope and purpose of why the document is required, what technical and physical evidence is included, and why it is being included. This allows the organization to consider all possibilities and determine what types of policies must be written and even how many policies are required.

A common mistake organizations face is writing a single policy document that encompasses a broad scope which is not easily understood and is difficult to distribute. Instead of having one large document to support all digital forensics requirements, multiple policies should be written to focus on specific evidence sources.

The type of policies to be written is subjective to the organization and its requirements for gathering and maintaining evidence. While there might be a specific type of policy documents not included below, Table 3.1 contains a list of common policies your organization must have in place to support digital forensics.

Table 3.1

| Policy | Scope |

| Acceptable use | Defines acceptable use of equipment and computing services and the appropriate end user controls to protect the organization’s resources and proprietary information |

| Business conduct | Defines the guidelines and expectations of individuals within the organization to demonstrate fair business practices and encourage a culture of openness and trust |

| Information security | Defines the organization’s commitment to globally manage information security risks effectively and efficiently and in compliance with applicable regulations wherever it conducts business |

| Internet and e-mail | Defines the requirements for proper use of the organization’s Internet and electronic mail systems to make users aware of what is considered acceptable and unacceptable use |

Guidelines

Following the implementation of a policy, guidelines provide recommendations for how the generalized policy blueprints can be implemented. In certain cases, security cannot be described through the implementation of specific controls, minimum configuration requirements, or other mechanisms. Unlike standards, these documents are created to contain guidelines for end users to use as a reference to follow proper security.

Consider how a policy requires a risk assessment to be routinely completed against a specific system. Instead of developing standards or procedures to perform this task, a guideline document is used to determine the methodologies that must be followed, allowing the teams to fill in the details as needed.

The type of guidelines to be written is subjective to the organization and its requirements for gathering and maintaining evidence. While there might be a specific type of guideline documents not included below, Table 3.2 contains a list of common guidelines your organization must have in place to support digital forensics.

Table 3.2

| Guideline | Scope |

| Data loss prevention | Awareness for end users on how to safeguard organizational data from unintentional or accidental loss or theft. |

| Mobile/portable devices | Recommendations for end users to protect organization’s data stored on mobile and/or portable devices. |

| Passcode selection | Considerations for end users to select strong passcodes for access into organizational systems. |

| Risk assessments | Direction for assessors to use documented methodologies and proven techniques for assessing organizational systems. |

Standards

After policies are in places, or as a result of a guideline, a series of standards can be developed to define more specific rules used to support the implemented governance documentation. Standards are used as the drivers for policies, and by setting standards, policies that are difficult to implement—or that encompass the entire organization—are guaranteed to work in all environments. For example, if the information security policy requires all users to be authenticated to the organization, the standard for using a particular solution is established here.

Standards can be used to create a minimum level of security necessary to meet the predetermined policy requirements. Standard documents can contain configurations, architectures, or design specifications that are specific to the systems or solutions they directly represent, such as firewalls or logical access. While standards might not reflect existing business processes, they represent a minimum requirement that must be adaptable and changeable to meet evolving business requirements.

The type of standard to be written is subjective to the organization and its requirements for gathering and maintaining evidence. While there might be a specific type of standard documents not included below, Table 3.3 contains a list of common standards your organization must have in place to support digital forensics.

Table 3.3

| Standard | Scope |

| Backup, retention, and recovery | Defines the means and materials required to recover from an undesirable event, timely and reliably, that causes systems and/or data to become unavailable. |

| E-mail systems | Define the configurations necessary to minimize business risk and maximize use of e-mail content as a result of the available and continuity of the supporting infrastructure |

| Firewall management | Defines the configurations necessary to ensure the integrity and confidentiality of the organization’s systems and/or data is protected as a result of the available and continuity of the supporting infrastructure |

| Logical access | Defines the requirements for authenticating and authorizing user access to mitigate exposure of the organizations systems and/or data. |

| Malware detection | Defines the configurations necessary to ensure the attack surface of vulnerable systems is mitigated against known malicious software. |

| Network security | Defines the requirements for controlling external, remote, and/or internal access to the organizations systems and/or data |

| Platform configurations | Defines the minimum security configurations necessary to ensure the organization’s system mitigates unauthorized access or unintended exposure of data. |

| Physical access | Defines the methods used to ensure adequate controls exist to mitigate unauthorized access to the organization’s premise. |

Procedures

From the guidelines and standards that have been implemented, the last type of documents to be created is the procedures used by administrators, operations personnel, analysts, etc., to follow as they perform their job functions.

Policies, standards, and guidance documents all have a relationship with digital evidence whereby they do not have direct interactions with the systems or data. On the other hand, procedures are documents whereby interactions with digital evidence is directly associated with the clearly defined activities and steps.

To better understand the different procedures involved with digital evidence management, each procedure will be explored throughout the remainder of this chapter as they apply to the different phases in the high-level digital forensic process model.

Essentially, the culture and structure of each organization influences how these governance documents are created. Regardless of where (internationally) business is conducted or the size of the organization, there are five simple principles that should be followed as generic guidance for achieving a successful governance framework:

• Keep it simple: All documentation should be as clear and concise as possible. The information contained within each document should be stated as briefly as possible without omitting any critical pieces of information. Where documentation is drawn out and wordy they are typically more difficult to understand, are less likely to be read, and harder to interpret and implement.

• Keep it understandable: Documentation should be developed in a language that is commonly known throughout the organization. Leveraging a taxonomy, as discussed in Appendix F: Building a Taxonomy, organizations can avoid the complication of using unrecognized terms and/or jargon.

• Keep it practicable: Regardless of how precise and clear the documentation might be, if it cannot be practiced then it is useless. An example of unrealistic documentation would be a statement indicating that incident response personnel is to be available 24 hours a day; even though there is no adequate means of contacting them when they are not in the office. For this reason, documentation that is not practicable is not effective and will be quickly ignored.

• Keep it cooperative: Good governance documentation is developed through the collaborative effort of all relevant stakeholders, such as legal, privacy, security, and human resources. If key stakeholder has not been involved in the development of these documents, it is more likely that problems will arise during its implementation.

• Keep it dynamic: Useful governance document should be, by design, flexible enough to adapt with organizational changes and growth. It would be impractical to develop documentation that is focused on serving the current needs and desires of the organization without considering what could come in the future.

Digital Forensic Team

Depending on the organization, a digital forensic team will vary greatly in terms of size, roles, and procedures. Regardless, there should be consistency in the requirement for all people involved in executing digital forensics activities and steps understanding the fundamental principles, methodologies, and techniques used during an investigation.

Roles and Responsibilities

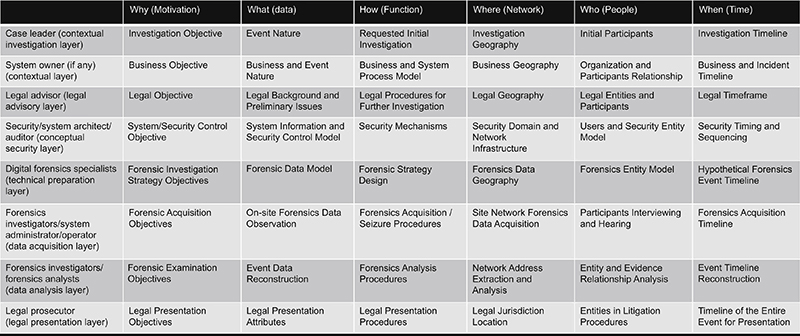

Illustrated in Figure 3.3, the FORZA—Digital Forensic Investigation Framework was developed as a means of linking the multiple practitioner roles with the procedures they are responsible for throughout the investigative workflow. Details on the roles described in the FORZA process model have been described in detail as found in Appendix A: Process Models.

Regardless of an individual’s role in the investigative workflow, there are different activities and steps performed that require either general or specialized knowledge in order to maintain digital evidence integrity. It is essential that all persons involved, at any phases of the investigative workflow, diligently follow the rules of evidence and thoroughly apply digital forensic principles, methodologies, and techniques to all aspects of their work.

Illustrated in the FORZA process model, the need for distinct roles and people is subjective to the overall size of the organization and the arrangement of the digital forensic team. For example, organizations that are smaller or localized to a specific geographic location might only employ a few individuals that are responsible for all aspects of digital forensics. Alternatively, organizations that are larger, distributed in geographic location, or have clearly defined structures might employ multiple individuals who are each responsible for a particular aspect of digital forensics.

Regardless of these factors, what remains consistent is the need for individuals who have strong information technology knowledge as well as formalized training of digital forensic principles, methodologies, techniques, and tools. These are essential and fundamental to ensuring that the integrity, relevancy, and admissibility of digital evidence are maintained. While not a comprehensive list, the following roles are commonly employed in support of digital forensics:

• Forensic technicians gather, process, and handle evidence at the crime scene. These individuals need to be trained in proper handling techniques, such as the order of volatility discussed in chapter “Understanding Digital Forensics,” to ensure the authenticity and integrity of evidence is preserved for potential admissibility in a court of law.

• Forensic analysts, or examiners, use forensics tools and investigative techniques to identify and, where needed, recover specific electronic stored information (ESI). Leveraging their technical skills, these individuals most often are the ones who are performing the work to process and analyze electronically stored information as part of an investigation.

• Forensic investigators work with internal (ie, IT support teams) and external (ie, law enforcement agencies) entities to retrieve evidence relevant to the investigation. In some environments, these individuals might also perform the duties of both the forensic technician and the forensic analyst. It is important to note that in some jurisdiction, use of the term “investigator” requires individuals to hold a private investigator license that involves meeting a minimum requirement for both education and experience.

• Forensics managers oversee all actions and activities involving digital forensics. Within the scope of their organization’s digital forensic discipline, these individuals can be accountable for ensuring their organizations digital forensic program continues to operate through activities such as leading a team, coordinating investigations and reporting, and oversee the execution of daily operations. While these individuals do not perform hands-on activities, it is expected that they are educated and knowledgeable of how digital forensic principles, methodologies, and techniques must be applied and followed.

While not typically a role within the digital forensic discipline, the terms forensic specialist and forensic professional are commonly used to describe individuals who have been extensively trained, gained significant amounts of experience, and are recognized for their skills.

Education and Certification

Dating back to the early 2000’s there has been a growth in the number of higher education and postsecondary institutes that offer education programs focusing specifically on digital forensic. While each education programs might be slightly different in the curriculum offered, they are all designed to cover the fundamental principles, methodologies, and techniques of digital forensics as required when directly involved in the investigative workflow.

Following the completion of formalized education, there are several recognized industry associations that offer professional certifications in digital forensics. It is important to keep in mind that on their own, these professional certifications do not provide the in-depth level of education and training on digital forensics and information technology that formalized education provides. Professional certifications, or professional designations, provide assurance that an individual is qualified to perform digital forensics.

Appendix B: Education and Professional Certifications provides a list of higher/postsecondary institutes that offer formal digital forensic education programs as well as recognized industry associations offering digital forensic professional certifications.

Lab Environment

A digital forensic lab is where digital evidence is stored. This lab environment must be both physically and logically secure so that evidence contained within is not lost, corrupted, or destroyed. When building a lab, there are common data center characteristics—including, but not limited to, power supply, raised flooring, and lighting—that must be factored into the construction of this controlled and secure environment.

In addition to data center characteristics, there are other attributes that must be considered to protect digital evidence from being lost, corrupted, or destroyed. The following items, in no particular order, provide additional protections against potential impact to digital evidence being stored within the lab environment:

• Labs must be built in an enclosed room, with true floor to ceiling walls, located in the interior of the building.

• To prevent unauthorized access, entrance door must have internal facing hinges, walls must be constructed using permanent materials, and windows must be reinforced with wire mesh material.

• Labs must follow the principle of least-privileged access and only permit access to those individuals who have been approved for entry.

• Physical access to the lab must be provisioned using multifactor authentication including something you know (ie, passcode), something you have (ie, smartcard), and something you are (ie, manager).

• Visitor access must be logged and escorted, at all time, inside the lab.

• Evidence lockers or safes must remain locked at all times with chain of custody logs tracking evidence ownership.

• Control mechanisms need to be created as parallel structures to track and maintain a complete, accurate, and up-to-date inventory of all major hardware and software items.

• Process and procedures must be in place to track access in and out of the lab, hardware and software inventory, and lab maintenance (ie, software currency, evidence lockers).

• Assignment of a custodian responsible for safeguarding digital evidence when it is not in use for processing by investigators.

Lab inspections must be performed consistently to provide assurance that the lab environment continues to operate with the established level of security controls in place. These reviews should be performed by independent parties and not by the digital forensic team to:

• determine if structural issues are present within the walls, door, windows, floor, and ceiling

• inspect all access control mechanisms to ensure they are not damaged and continue to function as expected

• review logs for physical access into the lab environment by both approved individuals and visitors

• analyze tracking logs to identify issues with continuity and integrity of evidence

Hardware and Software

With the digital forensic lab built, the team should begin to acquire a series of hardware equipment and software tools that will be needed to conduct investigations in a forensically sound manner. When acquiring forensic tools, it is important for the digital forensic team to keep in mind that each investigation is unique and may require a variety of different tools and equipment to maintain evidence integrity.

To identify and select the proper tools and equipment to perform their investigative activities and steps, the digital forensic team has to have a good understanding of how different business environments function respective to the hardware and operating system(s) they use. This assessment will determine what tools and equipment are required to gather and process evidence from the organizations data sources. While there might be some tools or equipment absent due to new ones being constantly developed, the websites included in the “Resources” section at the end of this chapter list some companies that have commercial offerings for digital forensic tools and equipment.

All digital forensic tools and equipment work differently, and may behave differently, when used on different evidence sources. Before using any tools or equipment to gather or process evidence, investigators have to be familiar with how to operate these technologies by practicing on a variety of evidence sources. This testing must demonstrate that the tools and equipment used during a forensic investigation generate repeatable4 and reproducible5 results. This process of testing introduces a level of assurance that the tools and equipment being used by investigators are forensically sound and will not introduce doubt into the evidence’s integrity. Appendix C: Tool and Equipment Validation Program outlines guidance for digital forensic professional to follow when performing testing of their tools and equipment.

Gathering

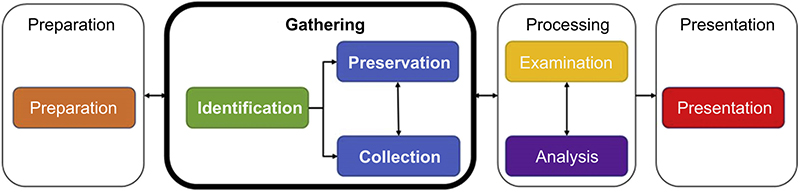

As the second phase of the investigative workflow, gathering is made up of the activities and steps performed to identify, collect, and preserve evidence. These activities and steps are critical in maintaining the meaningfulness, relevancy, and admissibility of evidence for the remainder of its life cycle (Figure 3.4).

Operating Procedures

Prior to gathering evidence, there must be a series of written and approved standard operating procedures (SOP) to assist the forensic team when performing evidence gathering activities and steps. The combination of governance that was developed through the information security management program, along with the validation and verification results from tool and equipment testing, operating procedures are the backbone for investigators to follow as they work through the investigation.

Identification

Identification of evidence involves a series of activities and steps that must be performed in sequence. It is important to know what data sources, such as systems, peripherals, removable media, etc., are associated or have an impacting role to the investigation.

When a data source has been identified, proper evidence handling must be followed at all times. If the evidence is handled incorrectly, there is high probability that the evidence will no longer be meaningful, relevant, or admissible. SOPs are required to support the investigative workflow and provide investigators with direction on how to execute their tasks in a repeatable and reproducible way.

Securing the Scene

Even though the main focus of digital forensics is about digital evidence, it is critical that digital forensic professional include both digital and physical evidence within the scope of every investigation. Similar to how the first step law enforcement takes is to establish a perimeter around a crime scene to secure evidence, the same first step must be done during a digital forensic investigation. Whoever is responsible for securing the scene must be trained and knowledgeable of the accepted activities, steps, and procedures to be followed.

Securing the physical environment, the current state of evidence can be documented and a level of assurance establishes that evidence will be protected against tampering or corruption. While the activities, steps, and procedures used will vary and are subjective depending on the environment, it is critical that they are followed to minimize the potential for errors, oversights, or injuries.

An important rule to remember in all crime scenes is that everyone who enters or leaves a crime scene will either deposit something or take something with them. It is crucial that no unauthorized individuals are within a reasonable distance of the secured environment as these persons can interfere with evidence and potentially disrupt the investigation.

At this phase, the information and details collected about the state of the scene is done so at the highest level. Proper planning must take place to develop and implement operating procedures that address the different scenarios for how to physically and logically secure crime scenes.

Documenting the Scene

Having secured the physical environment, the next step is to document the scene and answer questions around what is present, where it is located, and how it is connected.

The most effective way to answer these questions is by videotaping, photographing, or sketching the secured environment before any evidence is handled. When capturing images of the physical environment, the following aspects of the scene must be documented:

• A complete view of the physical environment (eg, floor location, department, workspace);

• Individual views of specific work areas as needed (eg, book shelves, systems, open cabinets, garbage cans);

• Hard wire connections to systems and where they lead (eg, USB drives, printers, cameras);

• Empty slots or connects not in use on the system as evidence that no connection existed;

• Without pressing mouse or keypad buttons, what is visible on the monitor (eg, running processes, open files, wallpaper).

Just like police officers record events in their notebooks, forensic investigators must maintain documentation for every interaction on the presumption that the investigation could end up in a court of law. The investigator’s notes must include (at a minimum) date, time, and investigator’s full name, and thorough details about all interactions. The notes should also illustrate page number/sequence and have no white space available—fill that space with a solid line to prevent supplementary comments from being inserted. A logbook template has been provided as a reference in the Templates section of this book.

Search and Seizure

Once the scene is secured and thoroughly documented, investigators work to seize evidence. But the goal of seizing evidence is not to seize everything at the scene. Through the knowledge and experience of trained investigators, educated decisions can be made about what evidence need to be seized and then documenting the justifications for doing so.

Digital evidence comes in many forms, such as application logs, network device configurations, badge reader logs, or audit trails. Given that these are only examples and depending on the scope of the investigation, there are potentially significantly more relevant evidence forms. Identifying and seizing all evidence can prove to be a challenging task to which technical operating procedures will provide guidance and support. However, from time to time, investigators might encounter situations where these technical operating procedures do not address collecting a specific evidence source. In these situations, the importance of having trained digital forensic professional is essential in having the knowledge and skills necessary to apply the fundamental principles, methodologies, and techniques of forensic science in seizing the evidence.

Documentation is at the center of the investigative workflow and is equally important when it comes to seizing evidence. When a physical (ie, computer) or logical (ie, text file) artifact has been identified as relevant to an investigation, the act of seizing it as evidence initiates the chain of custody to establish authenticity by tracking where it came from, where it went after it was seized, and who handled it for what purpose. Custody tracking must accompany the evidence and be maintained throughout the lifetime of the evidence. A chain of custody template has been provided as a reference in the Templates section of this book.

All digital evidence is subject to the same rules and laws that apply to physical evidence where prosecutors must demonstrate, without doubt, that evidence is in the exact and unchanged state as it was when the investigator seized it. The Good Practices Guide for Computer-Based Electronic Evidence was developed by the Association of Chief of Police Officers (ACPO) in the United Kingdom to address evidence handling steps for the types of technologies commonly seized during an investigation. Within this document, there are four overarching principles that investigators must follow when handling evidence in order to maintain evidence authenticity:

• Principle #1: No action taken by law enforcement agencies or their agents should change data held on a computer or storage media which may subsequently be relied upon in court.

• Principle #2: In circumstances where a person finds it necessary to access original data held on a computer or on storage media, that person must be competent to do so and be able to give evidence explaining the relevance and the implications of their actions.

• Principle #3: An audit trail or other record of all processes applied to computer-based electronic evidence should be created and preserved. An independent third party should be able to examine those processes and achieve the same result.

• Principle #4: The person in charge of the investigation (the case officer) has overall responsibility for ensuring that the law and these principles are adhered to.

Collection and Preservation

The transition between a physical investigation into digital forensic activities starts with the collection of digital evidence. Digital evidence is volatile by nature, and investigators are responsible for ensuring that the original state of seized evidence is preserved as a result of any tool or equipment used to collect it. Working in a controlled lab environment, investigators must create an exact, bit-level duplicate of original evidence using digital forensic tools and equipment that have been subject to validation and verification testing programs.

Under the Federal Rules of Evidence, Rule 1001 describes that duplicates of digital evidence are admissible in court instead of the original when it is “the product of a method which insures accuracy and genuineness.” To guarantee that the bit-level copy is an accurate and genuine duplicate of the original evidence source, one-way cryptographic algorithms such as the message-digest algorithm family (ie, MD5, MD6)6 or the secure hashing algorithm family (ie, SHA-1,SHA-2,SHA-3)7 are used to generate hash values of both original and duplicate. Not only does the use of one-way cryptographic hash algorithms provide investigators with assurance that the bit-level copy is an exact duplicate of the original, they also provide investigators with the means of verifying the integrity of the bit-level duplicate throughout the subsequent activities and task of the investigative workflow.

With an exact bit-level duplicate created for use during the processing phase, the original evidence must be placed back into secure lockup; accompanied by an updated chain of custody that documents the evidence interactions. In addition, a new chain of custody for the bit-level duplicate must be created and maintained throughout the remainder of the evidence’s lifetime.

Processing

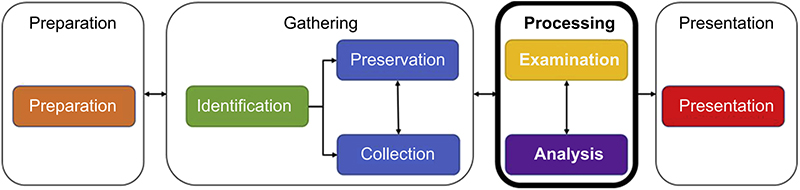

As the third phase of the investigative workflow, processing involves the activities and steps performed by the investigator to examine and analyze digital evidence. These activities and steps are used by investigators to examine duplicated evidence in a forensically sound manner to identify meaningful data and subsequently reduce volumes based on the contextual and content relevance (Figure 3.5).

All activities and steps performed during the processing phase should occur inside a secure lab environment where digital evidence can be properly controlled and is not susceptible to access by unauthorized personnel or exposure to contamination. Before performing any examination or analysis of digital evidence, investigators must complete due diligence by proving the integrity of the forensic workstations that will be used, including inspecting for malicious software, verifying wiped media, and certifying the host operating system (eg, time synchronization, secure boot8).

Maintaining the integrity of digital evidence during examination and analysis is essential for investigators. By using the one-way cryptographic hash algorithm calculated during the gathering phase, investigators can prove that their interactions do not impact the integrity and authenticity of the evidence. Digital forensic tools and equipment provide investigators with automated capabilities, based on previous professional knowledge and criteria, which can be used to verify and validate the state of evidence.

On occasion, the programmatic processes or algorithms provided through tools and equipment require extended and potentially unattended use of digital evidence. During this time, the investigator remains the active custodian of all digital evidence in use and is responsible for maintaining its authenticity, reliability, and trustworthiness while unattended. Within the controlled lab environment, access to evidence can be restricted from unauthorized access through the use of physical controls, such as individual work areas under lock/key entry, or logical controls, such as use individual credentials for accessing tool and equipment.

Presentation

As the fourth and last phase of the investigative workflow, presentation involves the activities and steps performed to produce evidence-based reports of the investigation. These activities and steps provide investigators with a channel of demonstrating that processes, techniques, tools, equipment, and interactions maintained the authenticity, reliability, and trustworthiness of digital evidence throughout the investigative workflow (Figure 3.6).

Having completed the examination and analysis, all generated case files and evidence must be checked in to secure lockers and the chain of custody updated. Unless otherwise instructed by legal authorities, the criteria for retaining digital evidence must comply with, and not exceed, the timelines established through policies, standards, and procedures. Proper disposal of digital evidence must be done so using the existing chain of custody form.

Documentation is a critical element of an investigation. In alignment with established operating procedures, each phase of the investigative workflow requires different types of documentation to be maintained that is as complete, accurate, and comprehensive as possible. From the details captured in these documents, investigators can demonstrate for all digital evidence the continuity in custody and interactions with authorized personnel.

Layout and illustration of the final report must clearly articulate to the audience a chronology of events specific to evidence interactions. This chronology should be structured in sequence to the phases of the investigative workflow and accurately communicate through defined section heading the activities and steps performed. A final report template has been provided as a reference in the Templates section of this book.

Summary

A critical component of every forensic investigation is the need for credible digital evidence abides with the legal rules of admissibility. Throughout the entire investigative workflow, there must be a series of administrative, physical, and technical in place to guarantee that the authenticity and integrity of digital evidence is maintained throughout its entire lifecycle.

Resources

Digital Forensic Tools and Equipment Tools, ForensicsWiki. http://www.forensicswiki.org/wiki/Tools, 2015.

List of Digital Forensics Tools, Wikipedia. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_digital_forensics_tools, 2015.

Free Computer Forensic Tools, Forensic Control. https://forensiccontrol.com/resources/free-software/, 2015.

21 Popular Computer Forensics Tools, InfoSec Institute. http://resources.infosecinstitute.com/computer-forensics-tools/, 2014.