Chapter 6

Identify Potential Data Sources

Abstract

Documentation of the data sources that are available as potential digital evidence is very important. While the purpose of this stage is to establish the scope of what data sources are readily available, it can also be used in support of a gap analysis to identify where digital evidence is not sufficient.

Keywords

Architecture; Breach; Context; Contracts; Evidence; Inventory; SourcesThis chapter discusses the second stage for implementing a digital forensic readiness program as the need to identify and document data sources. From establishing an inventory of the systems and applications where data is readily available, organizations can not only better determine where data relevant to digital forensic readiness program is located but also identify potential gaps in data availability.

Introduction

As the second stage, organizations must work from the risk scenarios they identified as relevant to their business operations. With each business scenario, work needs to be done to determine what sources of potential digital evidence exist, or could be generated, and what happens to the potential evidence in terms of authenticity and integrity.

Generally, the purpose of completing this stage is to create an inventory of data sources where digital evidence is readily available throughout the organization. This inventory not only supports the proactive gathering of digital evidence to support digital forensic readiness, but also allows the organization to identify systems and applications that are deficient in their data collection requirements.

What Is a Data Source?

Perhaps the most familiar technology where potential digital evidence is located comes from traditional computing systems such as desktops, laptops, and servers. Typically, with these technologies digital evidence will be located directly on the internal storage medium, such as the internal hard drive(s), or indirectly on external storage medium, such as optical discs or universal serial bus (USB) devices.

However, organizations should also consider the possibility that data source exists beyond the more traditional computing systems. With the widespread use of technology in business operations, every organization will have electronically stored information1 that is considered potential digital evidence generated across many different sources.

Careful consideration must be given when determining what potential digital evidence should be gathered from data sources. When identifying data sources, organizations should consider placing the potential digital evidence into either of the following categories.

Background Evidence

Background evidence is data that has been gathered and stored as part of normal business operations according to the organization’s policies and standard governance framework. The gathering of this type of evidence includes, but is not limited to:

• Network devices such as routers/switches, firewalls, domain name system (DNS) servers, dynamic host configuration protocol (DHCP) servers

• Authentication records such as directory service logs, physical access logs, employee profile database

• Electronic communication channels such as e-mail, text, chat, instant messaging

• Data management solutions such as backups, archives, classification engines, integrity checkers, transaction registers

• Other sources such as Internet service providers (ISP) and cloud service providers (CSP)

Foreground Evidence

Foreground evidence is data that has been specifically gathered and stored to support an investigation or identify perpetrators. The action of gathering this type of evidence can also be referred to as “monitoring” because it typically involves analyzing—in real time—the activities of subjects.2 Depending on regulations and laws concerning privacy and rights, organizations should consult with their legal teams to ensure that the active monitoring of employees is done correctly. The gathering of this type of evidence includes, but is not limited to:

• Network monitoring systems such as intrusion prevention systems (IPS), packet sniffers, Anti-Malware

• Application software such as Anti-Malware, data loss prevention (DLP)

• Business process systems such as fraud monitoring

While the above sample of data sources is by no means a complete representation of potential digital evidence, every organization has different requirements and will need to determine the relevance and usefulness of each data source as it is identified.

Cataloging Data Sources

Similar to how a service catalog provides organizations with a better understanding of how to hierarchically align individual security controls into the forensic readiness program, discussed further in Appendix D: Service Catalog, each data source must be placed into a similar hierarchical structure.

The methodology for successfully creating a data source inventory includes activities that have been completed previously, as discussed in chapter “Define Business Risk Scenarios” of this book, and as well as activities that will be completed afterward, as discussed in subsequent chapters of this book. Specific to the scope of this chapter, creating a data source inventory includes the following phases.

Phase #1: Preparation

An action plan is an excellent tool for making sure the strategies used by the organization when developing the data source inventory to achieve the desired final vision. The action plan consists of four steps that must be completed to deliver a complete and accurate inventory:

• Step 1: Determine what tasks and activities are required in order to identify data sources.

• Step 2: Identify who will be responsible and accountable for ensuring these tasks and activities are completed.

• Step 3: Document when these tasks and activities will take place, in what order, and for how long.

• Step 4: Establish what resources (ie, funding, people, etc) are needed in order to complete the tasks and activities.

At this point, there are several questions that organizations need to answer so that when it comes time to identifying and documenting data sources, they will be able to thoroughly and accurately collect the information needed to produce the inventory. In no particular order, these questions include:

• Where is the data generated?—Have the systems or applications that are creating this data been identified and documented in the organization’s service catalog?

• What format it is in?—Is the data in a structure that can be interpreted and processed by existing tools and processes; or are new tools or processes required?

• How long is it stored for?—Will the data be retained for a duration that will ensure availability for investigative needs

• How it is controlled, secured, and managed?—Is the authenticity, integrity, and custody of the data maintained throughout its entire life cycle?

• Who has access to it?—Are adequate authentication and authorization mechanisms in place to limit access to only those who require it?

• How much data is produced at a given interval?—what volume of relevant data is created that needs to be stored?

• How, where, and for how long is the data archived?—Is there sufficient resources (ie, network bandwidth, long-term storage, etc.) available to store it?

• How much data is currently being reviewed?—What percentage of the data is currently being analyzed using what tools and processes.

• Who is responsible for this data?—What business line within the organization manages and is responsible for each aspect of the data’s life cycle?

• Who is the data owner?—Identify the specific individual that is responsible for the data.

• How can it be made available for investigations?—What processes, tools, or techniques exist that allow this data to be gathered for investigative needs?

• What business processes does this data relate to?—What are the business or operational workflows where this data is created, used, stored?

• Does it contain any personally identifiable information?—Does the data contain any properties that can be used to reveal confidential or sensitive personal information?

Phase #2: Identification

Following the direction established in the action plan, organization will be better equipped to identify data sources throughout their environment where potential digital evidence persists. As data sources are identified, each must be cataloged and recorded in a centralized inventory matrix.

There are no predefined requirements indicating what specific elements must be included in the inventory matrix; leaving the decision to include or exclude elements entirely up to the subjectivity of the organization. The most common descriptive elements that organizations should use in the data source inventory matrix, as provided as a reference in the Templates section of this book, should include:

• Overall status provides a visual representation of the organization’s progress related to the gathering of digital evidence for the overall business scenario, including the following labels:

• Green (dark gray in print versions) = fully implemented

• Blue (black in print versions) = partially implemented

• Orange (gray in print versions) = in progress

• Yellow (white in print versions) = plan in place

• Red (light gray in print versions) = not implemented

• Business scenario indicates which of the business scenarios, as discussed in chapter “Define Business Risk Scenarios,” the data source contributes as digital evidence.

• Operational service aligns the data source to the operational service it is associated with as documented in the organization’s service catalog, discussed further in Appendix D: Service Catalog, such as digital investigations, litigation support.

• Data origin identifies the system or application where the information is generated; such as e-mail archive, end-user system, network share, CSP.

• Data category illustrates the exact type of information available in this data source; such as multimedia, e-mail messages, productivity suite documents.

• Data location determines how the information persists within the data source; such as at-rest, in-transit, in-use.

• Data owner documents the specific individual who is responsible for the data.

• Business use case identifies the high-level grouping representing the motive for why this information exists; such as DLP, data classification, intrusion prevention.

• Technology name documents the organization which created and provides ongoing support of the solution where the data source persists.

• Technology vendor documents the organization which created and provides ongoing support of the solution where the data source persists.

• Status provides a visual representation of the organization’s progress related to the gathering of digital evidence for the specific data source; including the following labels:

• Green (dark gray in print versions) = fully implemented

• Blue (black in print versions) = partially implemented

• Orange (gray in print versions) = in progress

• Yellow (white in print versions) = plan in place

• Red (light gray in print versions) = not implemented

• Status details provide a justification for the status assigned to the status progress rating for the specific data source.

• Action plan describes the activities required for the organization to improve the maturity rating for the specific data source.

Phase #3: Deficiencies

As the inventory matrix is being developed, the organizations might encounter instances where there is insufficient information currently available in a data source or gaps in the availability of information from unidentified data sources. Resolving these findings should be done separately because the activities that need to be performed are somewhat different in scope.

Insufficient Data Availability

Although a data source has been identified and included in the inventory matrix does not mean that it contains relevant and useful information to support forensic readiness. Generally, determining whether a data source provides an acceptable level of digital evidence requires that organizations ensure that the information contained within supports the investigation with either content or context.

Content Awareness

Content is the elements that exist within data that describes the details about an investigation. Information that can be used as digital evidence during an investigation must provide the organization with sufficient details that allows them to arrive at credible and factual evidence-based conclusions.

Commonly categorized as foreground evidence, information gathered from data sources should contain enough content to support the “who, where, what, when, how” aspects of an investigation. This requires that, at a minimum, all information within data sources that will be used as digital evidence must include the following metadata5 properties:

• Time stamp of when the event or incident occurred; including full date and time fields with time zone offset

• Destination of where the event or incident was targeted; including an identifier such as host name or IP address

• Description provides an unstructured, textual description of the event or incident

In addition to these minimum requirements, organizations must recognize that every data source is different and depending on the system or application that created it the information contained within will provide varying types of additional details. By assessing the content of a data source, organizations will be able to determine if it contains information that is relevant and useful as digital evidence.

Context Awareness

Context is the circumstances whereby supplemental information can be used to further describe an event or incident. Commonly categorized as background evidence, supplemental information gathered from data sources can enhance the “who, where, what, when, how” aspects of an investigation.

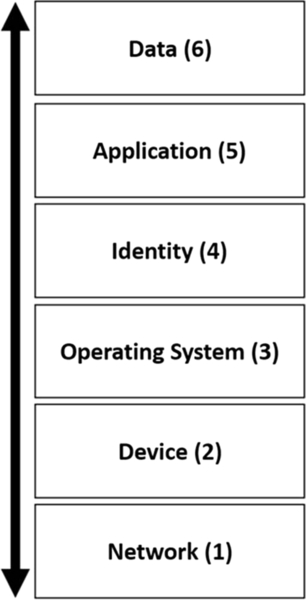

Consider a layered stack model, similar to that of the open systems interconnection (OSI) model,6 where each layer serves both the layer above and below it. The model for how context is used to enhance digital evidence can also be grouped into distinct categories that each provides its own supplemental benefit to the data source information.

A layered context model follows the same methodology as the OSI model where each layer brings supplemental information that can be applied as an additional layer onto the existing digital evidence. Illustrated in Figure 6.1, the attributes comprised within a layered context model includes the following:

• Network—Any arrangement of interconnected hardware that support the exchange of information.

• Device—Combination of hardware components adapted specifically to execute software-based systems.

• Operating system—Variations of software-based systems that manage the underlying hardware components to provide a common set of processes, services, applications, etc.

• Identity—Characteristics that define subjects6 interacting with software-based systems, processes, services, applications, etc.

• Application—Software-based processes, services, applications, etc. that allow subjects to interface (read, write, execute) with the data layer.

• Data—Structured and/or unstructured content that is gathered as foreground digital evidence in support of an investigation.

By applying meaningful contextual information to digital evidence, credible, and factual evidence-based conclusions can be reached in a much quicker rate because the team is capable of answering the “who, where, what, when, why, how” questions with a higher level of confidence and assurance.

Unidentified Data Sources

Before a decision is made to include these data sources in the inventory matrix, organization must first determine the relevance and usefulness of the data during an investigation. When assessing additional data sources, the business scenarios aligned to the digital forensic readiness program must be used as the foundation for the final decision to include or exclude the data source.

If a decision is made to include the data source into the inventory matrix, the organization will need to start back at Phase #1: Preparation discussed previously to ensure that the action plan is followed and all prerequisite questions have been answered.

External Data Considerations

Retrieving digital evidence from data sources owned by the organization can be relatively straightforward. However, with the continuous growth in using CSP7 there is a new level of complexity when it comes to gathering digital evidence from this type of data source.

For the most part, with these cloud environments, organizations do not have direct access to or ownership over the physical systems where their digital evidence can persist. This requires that in order to make sure that digital evidence will be readily available in an acceptable state (ie, integrity, authenticity), organizations need to ensure that a service agreement contract is established with the CSP where service-level objectives (SLO)8 for incident response are outlined.

Where a CSP has been contracted to manage and offer computing services, organizations must ensure that the service agreement between both parties includes terms and conditions specific to incident response and investigation support. Generally, the CSP must become an extension of the organization’s incident response team and ensure that they follow forensically sound processes to preserve digital evidence in their environment(s).

Organizations have to first obtain a reasonable level of assurance that the CSP will protect their data and respond within an acceptable SLO. The terms and conditions for how this assurance is achieved should be included as part of the services agreement established between both parties. Once the terms and conditions have been agreed by both parties, the roles and responsibilities of the CSP during an incident or investigation must be defined so that the organization knows who will be involved and what roles they will play.

Having established the terms and conditions specific to incident response and investigative support, it is essential that organizations involve the CSP when practicing their computer incident response program.

Data Exposure Concerns

The aggregation of data from multiple data source into a single repository will ensure that digital evidence is proactively gathered and is readily available during an investigation. However, the security posture of the aggregated digital evidence from the multiple data sources is extremely critical and should be subject to stringent requirements for technical, administrative, and physical security controls.

Essentially, the collection of this digital evidence into a common repository has the potential to become a single point of vulnerability for the organization. Completion of a risk assessment on this common data repository, as discussed further in Appendix G: Risk Management, will identify the organization’s requirements for implementing necessary countermeasures to effectively secure and protect the digital evidence.

Forensics in the System Development Life Cycle

Output from phase three of creating the data source inventory might lead to the identification of deficiencies in digital evidence availability (ie, insufficient log information) or additional relevant data sources that need to be gathered. In either case, organizations should consider the opportunity of integrating the requirements to support digital forensic readiness into their system development life cycle (SDLC). Examples of how digital forensic requirements that should be integrating into the SDLC include the following:

• Regularly performing system and application backups and maintaining it for the period of time as defined in organizational policies and/or standards.

• Enabling auditing of activities and events (ie, security, informational, etc.) of systems and applications (ie, end-user systems, servers, network devices, etc.) to a centralized repository.

• Maintaining a record of know-good and known-bad hash values of common systems and applications deployments.

• Maintaining accurate and complete records of network, system, and application configurations.

• Establishing an evidence management framework to address the control of data throughout its life cycle.

Summary

Digital evidence that is beneficial in supporting proactive investigations can be identified from a broad range data sources. When information from these data sources is being gathered, it must not only provide details about the incident or event, but also provide investigators with the contextual information necessary to make credible and factual conclusions. Furthermore, incorporating forensic requirements during the SDLC will enhance an organizations ability to gather digital evidence from data sources that is meaningful and relevant.