Jacopo Bellini, The Annunciation (detail of the central panel), early 1430s

This book set out to discuss paintings, but to do so it has been obliged to discuss words. I have tried to survey the big, broad categories within which we approach painting when we use such words as ‘imitation’, ‘nature’, ‘modernity’, ‘art’ and ‘realism’; and in giving historical shape to that practice I have invoked other standard abstractions, such as ‘knowledge’, ‘form’ and ‘time’. There is one concept to which I need to return in order to complete this survey, because in recent times it has served as a junction box for the rest. We have not done with words until we have explored the meanings of ‘representation’.

‘Representation’ is the label we commonly give to the age-old proposal about painting mentioned in chapter 1: that paintings are objects that show us, in two dimensions, objects we might potentially see in three. For a century and more, however, there have been objects which are undeniably paintings and which clearly don’t do this. People therefore got used to talking about ‘abstract’ paintings as well as ‘representational’ paintings, and in the mid-20th century it was often felt that there was outright opposition between the two categories. But more recently, during the later 20th century, arguments arose – we touched on some of them in the previous chapter – that every sort of painting was in some sense a representation, and was to be sceptically held to account for that reason. This factored into a many-levelled conversation about the ‘death of painting’. I should like to ask whether this conversation is itself now dead, before finally returning, after this tussle with words, to the speechless experience of looking.

Levels of Representation

Let me recapitulate some of the ways that the word ‘representation’ has been used by people who set out to discuss painting. These usages differ in scope and sometimes trip over one another.

(a) Pictorial representation. This is the idea mentioned above: the expectation that when you see this picture, you will recognize that physical object. Since we tend to think of physical objects as defining what is real, this kind of representation is often termed ‘realism’. It is this sense of representation that clashes with abstraction. When you look at a Mondrian, a Pollock or a Rothko, you cannot be reliably expected to think of any physical object other than the painting itself, whereas I should expect any person looking at the work above by Jacopo Bellini to recognize the types of object known as ‘woman’ and ‘bird’ within it – whatever else they might think of.

Jacopo Bellini, The Annunciation (detail of the central panel), early 1430s

Abstractionists produce paintings, but it might be said that they don’t produce pictures: because the bid to get viewers to think of 3D objects, the bid that Bellini is making, is what we generally speak of if we use the word ‘picture’. Pictorial representation, we tend to think, works when, and only when, the painting ‘looks like’ the object, at least to some degree; it is when the flat marked surface contains visual information that leads us to identify it with things external to itself. It is Plato’s and Aristotle’s mimesis, if you translate this as ‘imitation’ – that is, as making things like. It thus seems to be based on the possibility of resemblance.

(b) Symbolic representation. This is the idea I introduced when I spoke in chapter 1 of pictures as a type of sign: the expectation that when you see this picture, you will think of that meaning. When you see this picture of a dove face to face with a woman, you will understand that the former means the Holy Spirit – if, that is, you share the painter’s familiarity with this meaning, which is rooted in Christian doctrine. Symbolic representation, we tend to think, works because, and only because, there is an agreement within a certain cultural system that one thing may be substituted for another.

But this statement needs refining, because symbols can work two ways. Originally, Greek symbola were matching broken halves of a counter, used as pledges between people like ticket stubs. By extension, a symbol could be a likeness of a certain part of an original, taken for the whole of it. This relation is technically termed ‘synecdoche’. A roadsign showing a worker with a shovel is a kind of synecdoche: it gives us just enough of a likeness of the snarl-up of hard hats, jackhammers and rubble occurring further on down the road to get us ready for the forthcoming delay. Likewise, Bellini shows us what is recognizably a woman seen from a certain angle, allowing us to think of the woman who is the Virgin Mary.

But this is not what is happening when Bellini makes a bird stand for the Holy Spirit. The Holy Spirit doesn’t actually look like anything: it is by definition non-material. What is happening here is that one entire physical item is substituting for some other entire item, in this case something invisible but doctrinally crucial. Such a relation between two entire items constitutes a ‘metaphor’. It is the metaphorical relation between items that we typically call ‘symbolic’. A synecdochic representation is basically pictorial, being based on partial resemblance.

Symbols seem weaker than resemblances, insofar as they need a shared familiarity for their understanding. But symbols seem stronger than resemblances, insofar as they enable us to communicate abstractions. Words are symbols – sounds substituted for physical objects – because, and only because, we agree on these meanings. But they are also substitutes for non-physical concepts: in common with other symbols, such as mathematical figures and coins, words may represent entirely abstract notions of number and value.

Painters in modern times may express abstract ideas and invisible quantities, just as the medieval painter was doing. But as we saw in chapter 4, they are likely to be far less sure of communicating them. At the turn of the 19th century, the problem was posed by Philipp Otto Runge, the most conceptually radical of German Romantic painters: how could a new symbolism be found, as adequate to invoke people’s feelings as that of medieval and Renaissance painters had been? Painters, in an age where meanings had lost their fixity, needed ‘to search for concrete symbols which others have found before us, and try to match them to our feeling’. Morning, with its nature-based imagery, was Runge’s tentative, speculative solution. Over two centuries later, the problem has only got larger.

Philipp Otto Runge, Morning, 1808

(c) Representation as system. If symbols represent things because there is an acceptance within a cultural system that this may be substituted for that, then we might also use the word ‘representation’ to describe an overarching system that allows this to happen. Languages, numbers and currencies are systems of representation we are all familiar with. Each of them gives rise to items that are symbolically useful – words, decimal or binary figures, notes and coins. But there might be broader, deeper systems than these, giving rise to every sort of item that has meaning in human culture.

How could we identify such systems? Typically, we accept that this can stand for that because we find ourselves within a certain system or environment of meanings from the day we are born. And yet it is possible to contest such systems, at least in part. Theorists put forward overviews that purport to free us from them: notably Karl Marx with his class analysis of history, which describes systems of value that serve class interests as ‘ideologies’.

The most widely read book of art theory of the later 20th century, John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, presented an analysis of European painting tradition that leant on Marxism. Berger interpreted oil paint as a medium that sensually glamorized the textures of depicted objects and which therefore served an economic system pivoted on commodities and acquisition, in other words capitalism. An aspect that particularly resonated when Berger’s book came out in 1972 was the relevance of his arguments to the then burgeoning feminist movement. Prime among the objects glamorized by oil paint, Berger argued, was the naked female body offered up for male delectation. The female nude, as epitomized by Titian’s canvases, was a tradition that needed to be demystified.

An overview of a representational system could be used for a specific purpose such as this political critique, but it could offer more general intellectual liberation. The books that the philosopher Michel Foucault started bringing out in the 1960s were valued on campuses for this reason. Foucault presented histories of changing regimes of thought in post-Renaissance Europe. In these histories, supposedly fixed categories – truth, sanity, criminality, gender – stood exposed, in the light of a bracing scepticism, as makeshift constructs erected by systems of power.

But while scepticism is in a sense the essence of campus – the place to question everything – comprehensive scepticism would constitute a declaration of ‘ivory tower’ indifference (and hence irrelevance) to all real-world issues. Academics might therefore wish to allow a foothold for the real in their intellectual schemes. The Marxian art historian T. J. Clark invoked ideologies clashing in a war of ‘representations or systems of signs’ in his influential book about Manet and the Impressionists, The Painting of Modern Life (1984). For Clark, ‘society is a battlefield of representations, on which the limits and coherence of any given set are constantly being fought for and regularly spoilt’. By this logic, reality would be the limits that each class-based representation came up against.

(4) Representation as structure. We looked in chapter 2 at other theoretical schemes relating reality to representation. Kepler’s 1604 comparison of eye and camera suggested that vision was a matter of representing the world to the mind; and hence, to thinkers from Descartes to Kant who developed this approach, that knowledge was a matter of ‘mental representation’. In the 19th century, this idea was developed by the scientist Hermann von Helmholtz, who offered an account of all experience coming to consciousness in the form of ‘signs’. It was also developed in logic by the American C. S. Peirce, with his ‘semiotics’ – an exhaustive classification of such signs – and by the German Gottlob Frege, working in the 1890s.

Frege discriminated in his account of linguistic representation, distinguishing reference – the relation of the sign to the thing – from sense – the relation of the sign to its context. Reference and sense are interdependent; when the sign and its context take the form of word and sentence, ‘it is only in the context of a sentence that a word refers to anything’. This was a crucial distinction for thinkers in his wake: Wittgenstein in his earlier philosophy treated every reference as a ‘picture’ corresponding to reality, so that the sense of sentences that contained them was potentially like that of a map, or the index to a file of photographs.

With differing emphases, Frege and the earlier Wittgenstein were adopting what could be broadly termed a ‘structural’ way of thinking. That is to say, they were setting the subjects of their thought on two intersecting planes. One of them – in Frege’s terminology, ‘reference’ – is equivalent visually to a moment of looking, a certain perception of a certain thing, what we might call an atom of experience. The other – ‘sense’ – is a structure that is not experienced in its own right, but which contains and determines experience.

This way of thinking can be seen not only when Marx talks about ‘ideology’ as a force that can invisibly shape experience into ‘false consciousness’, but equally in Freud’s theories of an ‘unconscious’ that determines the shapes of immediate perception. Freud’s work of the 1900s and 1910s ran alongside the linguistics of Ferdinand de Saussure. In these, as in Frege, it is not the relation of word to thing that determines meaning, but the relation of word to language as a total structure. Words do not get their meaning positively, by resemblance to things, but negatively, by difference from other words.

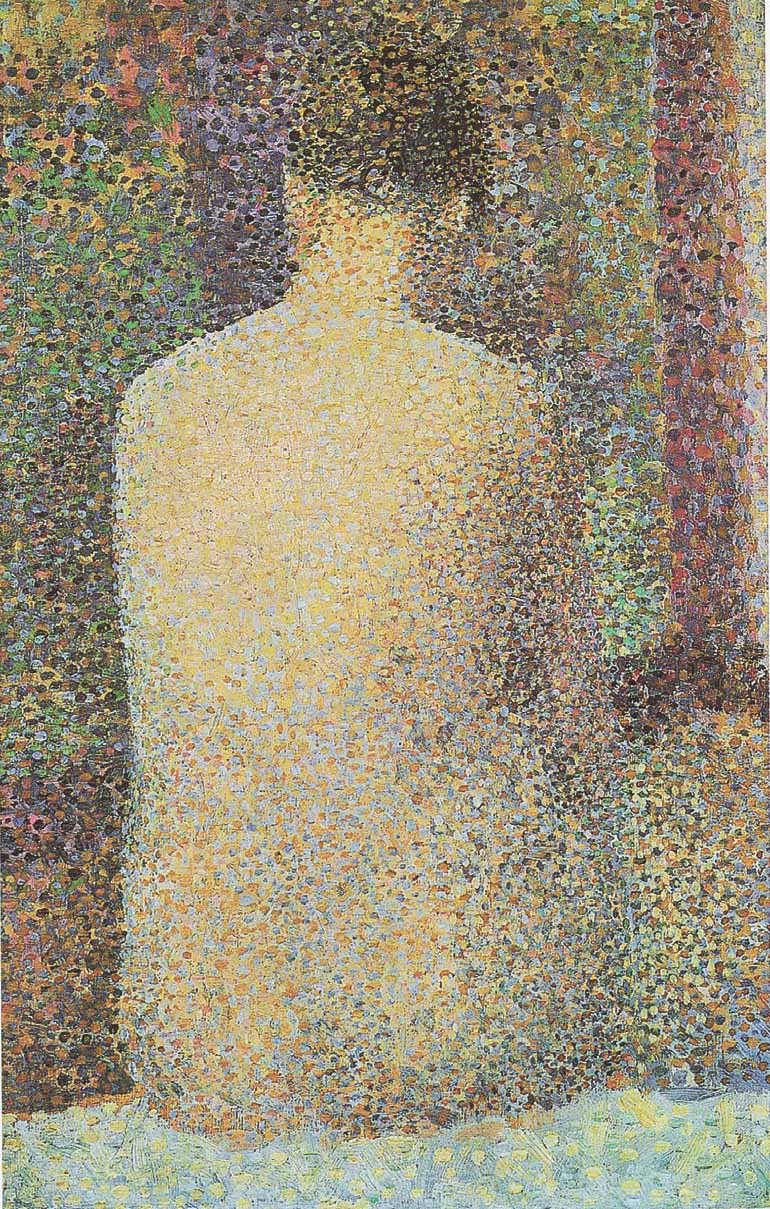

Structural thinking had analogues in the visual arts: the attempt to treat colour as a law that organizes perceptions or ‘sensations’, seen for instance in the paintings of Seurat; or, in the 1910s, Cubist collage, in which anything may represent anything by virtue of its place within a complex of excerpts. As the philosopher Jean-François Lyotard put it, painters from Cézanne onwards concerned themselves ‘to make seen what makes one see, and not what is visible’. The modernist era in art history, interpreted by Greenberg as a purification of painting’s means, could be read this way also – as a progressive exploration of the structures that inform vision.

Georges Seurat, Nude, 1887 (sketch for Les poseuses)

One characteristic tactic of ‘structuralism’, as it was defined by the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss from 1949, has been employed in this book. To propose a matrix of terms for painting, as at the end of chapter 1, is to suggest that feelings and perceptions are organized within certain abstract oppositions, and that experience can be mapped out as an expanse determined by their co-ordinates. The structuralists of Lévi-Strauss’s generation, however, characteristically went on from this to assert that the total structure had priority over the particular experience. Human experience was dependent on structures, whether you conceived of them on a social or a psychological level. They produced what Roland Barthes called ‘the effect of the real’, and this production was ‘representation’.

María Elena Vieira da Silva, The Corridor (La Chambre Grise), 1950

Again there is some analogy between this way of thinking and contemporaneous approaches to painting. One of the recurrent images of mid-20th-century painting is what could be called the ‘field’ – the whole expanse of the picture treated as a totality within which objects, events or effects come into being. It is an image that cuts across the abstract / representational divide; it comes up in the fields of markings created by painters such as Paul Klee, Lyonel Feininger, Mark Tobey, Victor Vásárely or María Elena Vieira da Silva, in the ‘colour-field’ work of 1960s painters such as Morris Louis, or in the observational exploration, mentioned in chapter 2, of the ‘visual field’. In all of these, as in Barthes’s phrase, reality is an emergent effect.

‘Theory’

Have painters traditionally taken their cues from academic theorists, or has it been vice versa? For the most part, neither is true. Cultural history may reveal premises and methods loosely held in common, but it rarely has direct influences to trace. If many painters in the later 20th century turned away from the ‘high art’ values of abstraction, it is unlikely that many read the later philosophy of Wittgenstein. Nonetheless, there is some illumination in the comparison. Wittgenstein’s later work sought to escape from his earlier philosophy, and from the whole split framework within which representation had been conceived in the earlier 20th century.

‘A picture held us captive’, he wrote, characterizing the linguistic bind he was seeking to escape – the picture being one of those window-like affairs dreamt up by Giotto and favoured by Alberti. This picture had captivated the earlier Wittgenstein and his generation because, taken as a model of reference, it seemed to open out the possibility of viewing the thing by itself and for itself – even while that view hung framed in the museum-like context supplied by ‘sense’. As it was actually used however, spoken and written language – claimed the later Wittgenstein – was not anything like a museum: it was more like an outdoor, loosely regulated, constantly shifting game between individuals. There were no atoms of experience, he claimed, no isolated moments of pure primary perception in which we could simply gaze at a picture of the thing itself. Pictures, whether verbal or visual, were always seen ‘as’ something, always being described even in the process of perception.

This later teaching of Wittgenstein’s, which began to be published after his death in 1951, left off approaching representation as a fixed interplay of pure reference with pure structure, focusing instead on utterances made in interpersonal dialogue. Meanwhile New York artists of the 1950s and 1960s, starting with Rauschenberg, dismissed the pure ‘optical’ experience of painting on which Greenberg insisted, putting together exhibits that embraced the street beyond the gallery doors in all its factuality, materiality and temporality. Impulses of this sort would resonate ever more widely through later 20th-century art.

While structuralism spread from Paris into anglophone campuses during the 1960s, its whole approach was being undermined, from angles other than Wittgenstein’s, by further French theorists. Jacques Lacan’s interpretations of Freud gained a growing audience at this time, describing human psychology as not only a system of differences but a continuity lacking any centre, with the watchful ego bedded down amidst the symbolic structures within which it was seen as emerging. A decentering strategy was also pursued by Jacques Derrida in Of Grammatology, a book published in 1967 and influential through the following three decades. Derrida’s account of writing started where chapter 4’s account of painting left off: denying the possibility of complete communication. I write, and you read, now; but the sense of that word divides rather than unites us. All writing, he claimed, divides sense in this way, so that meaning is always already one step down the line; it resides nowhere, in a full experience of full presence, but is always deferred. It was disseminated across a structure that therefore had no kind of substance; therefore ‘there is no representation of representation’.

Derrida fashioned statements that drew attention, with great sophistication, to their own inadequacy and inescapable incompleteness. In the later 20th century such statements could be encountered in visual art as well as in theory. Notably, Gerhard Richter talked of his photo-painting as a conscious obstruction of communication:

Life communicates itself to us through convention and through the games and laws of society. Photographs are ephemeral images of this communication – as are the pictures that I paint from photographs. Being painted, they no longer tell of a specific situation, and the representation becomes absurd…A picture presents itself as the Unmanageable, the Illogical, the Meaningless. It demonstrates the endless multiplicity of aspects: it takes away our certainty, because it deprives a thing of its meaning and its name.

Richter transcribed photographs with one hand, but with the other (as it were) he swiped and smeared abstractly and seemingly argumentatively – as if to assert that both tactics were equivalent in their communicative insufficiency. They failed to deliver, he said, what one might hope for from high art: ‘I see myself as the heir to an enormous, great, rich culture of painting, and of art in general, which we have lost, but which nevertheless makes requirements of us.’ A comparable note of historical pathos was struck by Francis Bacon lamenting that it was no longer possible to paint like Velázquez:

Gerhard Richter, Table, 1962

You see, all art has now become completely a game by which man distracts himself; and you may say that it has always been like that, but now it’s entirely a game. And I think that that is the way things have changed, and what is fascinating now is that it’s going to become much more difficult for the artist, because he must really deepen the game to be any good at all.

But if the outlook seemed overcast to these prominent painters of the later 20th century, the prospects for those working in humanities departments seemed bright. For them, to invoke ‘theory’ was to salute a range of Paris-based authorities, both structuralist and ‘post-structuralist’ (i.e. sympathetic to Derridean deconstruction), including Lacan on the formation of ‘subjectivity’ or selfhood and Julia Kristeva on its fluidity; Foucault on the way that power informed the ‘representations’ of knowledge and social control; Luce Irigaray on representations of gender; and many sources besides. To talk of ‘intertextuality’ – a coinage of Kristeva’s – was to celebrate and urge on this academic proliferation. A characteristic prospectus for a ‘theory’ course stated that:

Francis Bacon, Study after Velázquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, 1953

the unit will…consider those theories, principally of the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, which undermine and critique the idea of representation, and which instead emphasise representation as the production and interpretation of ‘knowledge’ of a reality which cannot, in knowable form, pre-exist its representation.

The idea of representation, given the tortuous phrasing I have italicized, could be restated as a kind of myth, if we take ‘myth’ to mean a widely shared story about origins, as to the worth of which we suspend judgment. As I see it, the myth falls into two parts:

Representation is (or rather, was) an invisible spatial array – a configuration, a matrix, an abstract geometry – within which experience takes place. Within it, subjects like ‘you’ and ‘me’ and objects like ‘this’ and ‘that’ come into being: they exist purely as differences, as effects of spacing, within this total array.

But – representation itself does not exist. It is an idea, like God, invented to give things a backup promise of fixity, meaning and presence that they cannot deliver. If meanings shift, this suggests that there is a space within which they can shift. But to define this space is to fall into error: there is no all-encompassing geometry, there is only the local emergence of difference.

The appeal of this myth was that it could be used to deny substance both to the particular and to the abstract. As such it seemed to promise intellectual liberation, not only from the particular – as most philosophies do – but from the intellectual tyrannies most philosophies set up in its place. Spreading in the 1980s to anglophone art studies, the approach was adopted and adapted by writers such as Norman Bryson and Rosalind Krauss.

At the same time, this eager adoption of ‘theory’ in the humanities pointed to a type of insecurity. What legitimated the study of culture, of human meanings and expressive actions? In order to maintain its intellectual status, did such study need to bind that live material within quasi-scientific neutral geometries? Or might it somehow fuse objectivity with subjectivity, overriding existing intellectual boundaries? Some exponents of ‘theory’ seemed to want to do this: some academics from the other side of campus hit back, notably the mathematician Alan Sokal who in 1995 damaged his opponents’ credibility by getting them to publish a deliberately nonsensical spoof-theoretical article. From that point onwards, theory-based approaches to the humanities have tended to fall back onto the defensive.

It is true that the humanities have sought other ways to latch onto scientific authority. Some have gone to fMRI scans that offer pictures of what happens in the brain when a viewer looks at a painting. Semir Zeki, a scientist who analysed the processes occurring in the cortex and speculated how these might relate to concepts of beauty, came up with the formulation that, ‘Artists are in some sense neurologists.’ Modernist artists, at least: Zeki was restating Lyotard’s aperçu, mentioned earlier in this chapter, that these, with their focus on isolated colours and forms, were painting ‘what makes one see’. It remains an open question whether the new ‘neuroaesthetics’ can do anything other than re-express in physical terms experiences and insights already familiar to working artists.

But if art studies have arrived at an insecure relation to science, artists’ studio practices have arrived at an insecure relation to art studies. The chief reason is that over the past half-century art education has been largely brought within standard university constraints, with would-be artists now expected to produce extended and rigorously referenced written work in order to gain qualifications. (There is also the consideration that curators – the people artists may need to answer to, to gain public attention – will be professionally versed in art studies and its subject jargon.) As a result the studio’s doors have been thrown open to the systematic questioning and principled scepticism that inherently belong to campus.

This is an awkward cohabitation. We have two sorts of skill here: ‘liberal arts’ that make demands on speech faculties, and the skills of hand and eye required to make physical objects. Even if neurology tells us nothing else, it points out that these use different parts of the brain. The tempos are different too. Critical debate is characteristically quickfire, while the hands-on making of an object worth looking at is very likely to be a slow, day-in, day-out process. From the 1970s onwards, an increasingly frequent response to this mismatch has been for the decision-making graduate – the art executive – to outsource the manufacture of the work itself to fabricators. (The immediate prototype for this division of labour was the practice of Donald Judd – see chapter 5 – though it could be traced back to the Constructivist László Moholy-Nagy painting by telephone in 1922, in other words sending instructions for the colouring of panels down the line to a sign factory.) Concurrent with this tendency, the wordsmiths of art started to reach for an old familiar trope: ‘the death of painting’.

‘The Death of Painting’

The death of painting has been several times announced. We have noted Delaroche’s response to the arrival of photography in 1839. There was also the intuition of many Constructivists, mentioned in chapter 3, that painting had become obsolete in an age of revolutionary transformation. ‘I reduced painting to its logical conclusion and exhibited three canvases: red, blue and yellow. I affirmed: it’s all over.’ That was Rodchenko’s funeral for the art in 1921. Walter Benjamin, writing in 1936, effectively agreed: painting had no ongoing role in a history now driven by dynamic mass politics.

Talk of the death of painting is also echoed in the pessimism that has coloured many painters’ imaginations. Francis Bacon, believing that God was dead and that, therefore, one could no longer describe human beings with the religious conviction that Velázquez once possessed, spoke as if this forced painting into a corner: ‘now it’s entirely a game’. Richter too invoked a history of decline in speaking of the ‘enormous, great, rich culture of painting, and of art in general, which we have lost’. Both, it might be said, reflected a lugubrious take on current historical conditions that was widespread in later-20th-century cultural circles. At the end of the modernist venture in art and of the horrors modern times had witnessed, a late-evening stormlight shone on culture. Soon it would be sundown, and then what use would there be for the old high-cultural forms? Yet it might be added that myths of loss often serve as imaginative catalysts, helping painters to make something constructive out of their anxieties about overbearing predecessors. Surely Velázquez himself was aware of being a latecomer, challenged by the masterpieces that Titian had painted during the previous century for the Spanish royal collection.

But the death verdicts for painting that circulated from the 1980s onwards were not nostalgic in complexion. They were first pronounced in New York, by academic critics such as Douglas Crimp (in his essay ‘The End of Painting’, 1981), but it might well be said that some painters in that city had already brought these sentences down upon their own practice. During the 1960s, while Greenberg urged artists to concentrate on the means of their art, Ad Reinhardt, a contrarian quite as argumentative as he, outflanked his call for purity by exhibiting Ultimate Paintings consisting of subtly differentiated squares of black. A Reinhardt canvas was meant to be unsurpassable in its negations:

a pure, abstract, non-objective, timeless, spaceless, changeless, relationless, disinterested painting – an object that is self-conscious (no unconsciousness), ideal transcendent, aware of no thing but art (but absolutely no anti-art).

Supposing you took this seriously and that you still wanted to make something to look at, you would surely need to step away from a medium that had, by Reinhardt’s choice of epithet, arrived at its final destination. (When Rothko committed suicide in 1970, a common reaction was that he too with the ever narrower terms of his ‘signature style’ had reached a veritable dead end.)

You might from this point move on as an artist by adopting wholesale the Minimalist aesthetic half implied by Reinhardt’s rhetoric. You might make a physical object which still involved paint, but if so, it would lack the duplicity that any figure-ground, colour-against-colour relationship sets up. You would thereby escape the strictures of Donald Judd, who disapproved of the invention of visual fictions as a matter of philosophical principle. And if you also eschewed manual brushwork, you would avoid the scorn that Judd’s co-exhibitor Robert Morris expressed for ‘tedious object production’. You would hardly have made anything like a painting, in the historical sense of the term.

Alternately, you might accept that 2D representations were inescapable, and that this inescapability – in a capitalist system where publicity images endlessly proliferated – was itself a condition that artists needed to address. This much was accepted by the painters who created 1960s Pop Art, but in the wake of Minimalist critiques, it was no longer obvious to the upcoming artists of the following decade that paint was a fit medium to tackle the issue of what ‘pictures’ now involved. You might more incisively use photography to criticize photography, or the new medium of video to transact between source and reproduction. If American artists of this ‘Pictures generation’ – Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, Sherrie Levine, et al. – dealt in painting at all, it was in order to contextualize and ironize that particular cultural practice, generally through ‘appropriation’. In other words, through image quotation. Levine gave handsome expression to its rationale in a 1981 text:

‘The Black Square Room’, Ad Reinhardt exhibition at the Jewish Museum, New York, 1966–7

The world is filled to suffocating. Man has placed his token on every stone. Every word, every image is leased and mortgaged. We know that a picture is but a space in which a variety of images, none of them original, blend and clash. A picture is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centres of culture. Similar to those eternal copyists Bouvard and Pécuchet [in Flaubert’s novel of that name], we indicate the profound ridiculousness that is precisely the truth of painting.

Levine’s sceptical cancellation of originality was paralleled in the writings of Jean Baudrillard, whose accounts of ‘hyperreality’ – a state of affairs in which no prior reality exists and all is always copy (or ‘simulacrum’) – captured, for many in the 1980s and 1990s, the texture of the postmodern world. Wised up in this way, ‘Pictures’ artists adopted the anti-expressionist (or ‘anti-humanist’) mindset discussed in chapter 4. What mattered at the turn of the 1980s to the academically articulate artist was to battle against the emotional self-indulgence displayed by ‘Neo-expressionists’ such as Sandro Chia or Julian Schnabel. All the more so, because of the latters’ success in marketing florid impastos and deliberately goofy, ‘bad’ brushwork as demonstrations of a supposed fresh resurgence of painting. For the New York theorist Craig Owens, Neo-expressionism constituted ‘a desperate, often hysterical attempt to recover some sense of mastery’, indicative of last-ditch anxieties about a loss ‘of virility, masculinity, potency’.

Owens staked out an opposition to any pretended revival of painting on principle, expressing his solidarity with feminism as a gay activist. The contention was that a tradition headed by artists like Titian, Picasso and Pollock bore an inherently aggressive patriarchal demeanour. As Berger had already argued, this medium had a historical complicity not only with capitalism but with the objectification of women, and this complicity could best be addressed by stepping outside it.

If in the studio you might do so by appropriation, on campus you might do so by appealing to the concept of ‘the gaze’. The term, adapted in 1975 by the film critic Laura Mulvey from Lacan’s le regard, indicated a field of visual tension within which subjects and objects separated and polarized. Equipped with this concept, you could approach the watcher’s relations with the watched (whether these were male with female, ruler with ruled or audience with artwork) not simply in terms of opposition, but rather as a psychological ecosystem. It was unlikely that you would describe that ecology neutrally, however. If you synthesized this idea with Foucault’s schemata that described the history of knowledge as a history of power relations, you would arrive at a ‘gaze’ that had operated as a macho, malevolent dictator, locking genders, classes and perhaps ethnicities into a long-term historical pathology – of which painting itself was merely a symptom.

The ‘death of painting’ theme, then, combined lofty intellectual overviews with an everyday doubt that had beset many an artist during the 20th century and that continued through its final, ‘postmodern’, decades: weren’t there better ways to make things nowadays, rather than sticking with old-fashioned oil paint and canvas? The theme also found its place in a culture in which leftwing projects of social transformation were being pushed onto the defensive. Their best hopes now of realization lay not in mass action, but in cultural guerrilla warfare conducted from the sanctuary of the campus. And because of the closer mesh between humanities education and the politics of exhibiting, the rearguard fight was also being conducted from those associated free zones, the ‘white cubes’ – the galleries of contemporary art.

Sandro Chia, The Water Bearer, 1981

Reflecting on the context underlying the ‘death of painting’ in a 2003 colloquium, Lane Relyea sketched the view as it appeared from his chair on an American campus:

Sometime between the ’60s and the ’80s, discourse replaced painting as the dominant medium in the art world…The pervasive sense that artworks are a subspecies of discourse, that they depend for their legibility, their legitimacy, on discourse – that they are most fully revealed in books and magazines, in dual-slide-projector lectures and artists’ talks, in informed discussions among art-world professionals – did much to erode conviction in the single static image…It’s in this context that perhaps it makes some sense to say that paintings ‘look better in reproduction’.

The analysis is provocative and apt. But by 2003, when Relyea was speaking, it had become clear that easel painting had failed simply to die the death, in the way that miniature painting once had (an art which, as it happens, was itself experiencing a startling revival, among artists associated with the National College of Arts in Lahore). Some of the reasons why are mundane. For all the steel-and-glass and flow-through space of contemporary exhibition venues, most of them still end up with some interior walls, and if these walls are to be punctuated with exhibits to look at, it is very, very hard (though not necessarily impossible) to find a medium that delivers anything to match the visceral impact and complex emotional and intellectual engagement provided by a strong painting – however much compromised and complicit historical baggage that artefact may inject into the pristine architecture, or perhaps exactly because it is prone to carry such a turbid weight.

Moreover a supply of at least sufficiently strong painting was on offer throughout the ‘death of painting’ era, thanks to the residual resilience of a product tradition supported by large investments of expertise, equipment and designated workspaces (i.e. studios). For instances I could appeal to my own tastes – in this text I have mentioned Kiefer, Basquiat, Mehretu, Abts, there could have been so many others – but the bottom line is the question of whether artists in other media have produced wall hangings of unarguably richer interest than these, or than whatever your own preferred roll call may be. Many of us might want to argue that our chosen survivor painters from this era came through exactly because the critiques of the medium put them to the test and obliged them to think harder. Painting has had to work for a niche in the limelight: it can no longer assume, as it could until the 1960s, that it tops the hierarchy of the arts. And that is proper; good riddance to hierarchies! But the pattern that emerges would satisfy any conservative historian: painting’s survival as a case of modulated continuity.

In asking what medium generates more ‘interest’, I’m aware of touching not only on the history, but on the rights and wrongs of the now more or less exhausted debate. ‘A work needs only to be interesting’: so said the fact-loving Donald Judd, proposing that a ‘specific object’, a simple, physical 3D thing, could give out more to the viewer than a flat, multicoloured, illusionary juggle of optical stimuli. Plato the idealist would come to the same conclusion, if for opposite reasons: at least the simple object would bring the viewer nearer to the God-given original form. In their own terms, there can be no arguing with either. But if there is a commentator who is able at once to oversee and to overturn both, it is Friedrich Nietzsche:

If we had not approved of the arts and invented this kind of cult of the untrue, the insight into universal untruth and mendaciousness now provided to us by science – the insight into illusion and error as a condition of knowing and feeling existence – could in no way be endured.

I’d add three footnotes to that sardonic oracular pronouncement. Firstly, if the love of painting is a kind of cult, cults take hold because they offer sweetness, as well as relief from anxiety: but to say that sweetness – pleasure – is itself an illusion, would be a category mistake. Secondly, that visual arts in general are caught up in this: it is not only painting that leans on the comforting appeal of myth, expressionism and optical pizzazz, but most (admittedly not all) of its alternatives. Witness, for instance, the popular work of Damien Hirst, presenting traditional metaphors dressed up in post-Minimalist décor. Thirdly, that this isn’t at heart a cult of the untrue. Myth is basically inescapable. We all have to reach for some overarching story-about-conditions that we might be able to trust. Painting can be a way of so reaching.

Picturing Painting

So what is painting? That has been the question underlying this whole book. What principle holds together those objects called ‘paintings’? The answers to these questions seem to keep shifting, as we have examined various facets of theory and practice. But that is not to say, I think, that the answers drift rootlessly: there is a cohesive logic to the movement of our feelings about paintings.

No, there is no single way to describe painting. Rather, I think the account given in this book can be summarized in a fourfold model. I would propose four broad modes for our feelings towards paintings, and suggest that these modes relate in a defined fashion.

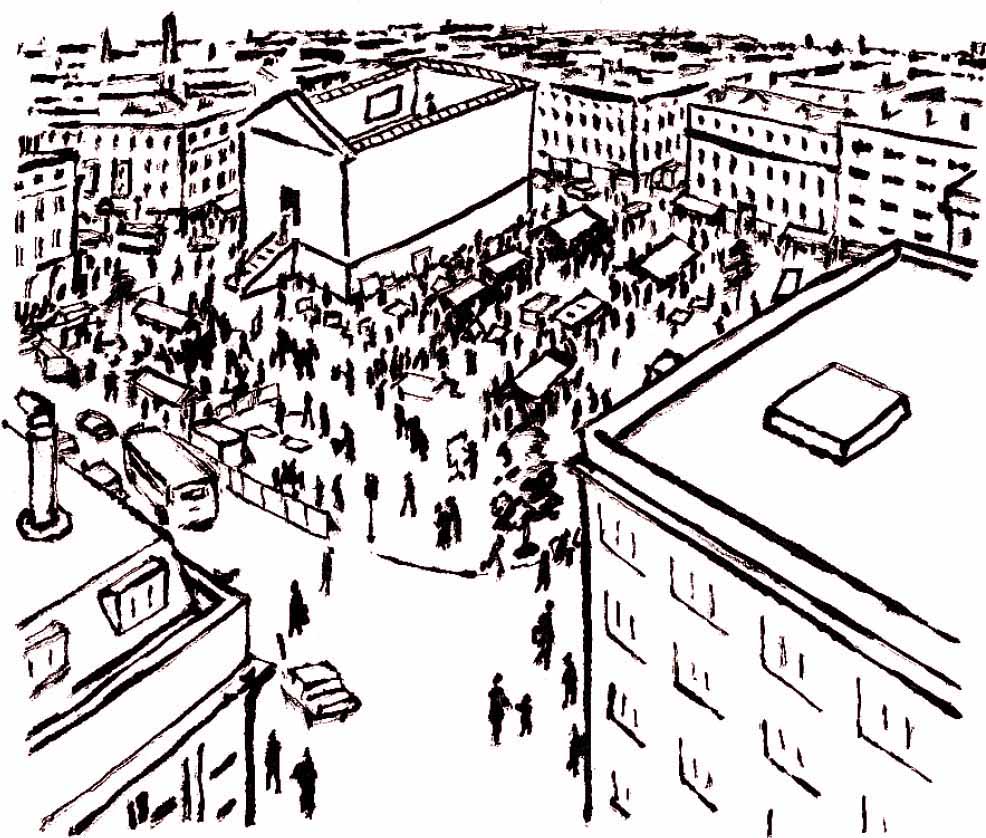

What I mean may emerge if we consider two spatial images that have arisen in the course of this account. One (put forward in chapter 2) sets the topic of the book socially: the market-place (or funfair) that offers products or ‘paintings’, as against the associated big store (or institution) that encloses the cohesive practice of ‘painting’. The other (offered in chapter 4) considers the issue personally, asking how the terms of ‘body’, ‘mind’, ‘spirit’ and ‘self’ relate to vision. Let us picture each of these two levels of operation.

Here is a bird’s-eye view of the market-place, where pictures are hawked in a confused hurly-burly. Passing through it on our way across town, we may not be sure exactly what they mean: we may like them, perhaps think of them as pretty, eye-catching diversions, as ‘fun’. To the side of this market-place the institution – big store, academy, museum – has been set up to concentrate the mind on art. Within, there is order, and you can banish time through silent, serious looking: aesthetic contemplation. Of course, we must remember that the market, and to a secondary degree the museum, rely on goods coming in from without.

Painting’s market-place (drawn by Julian Bell)

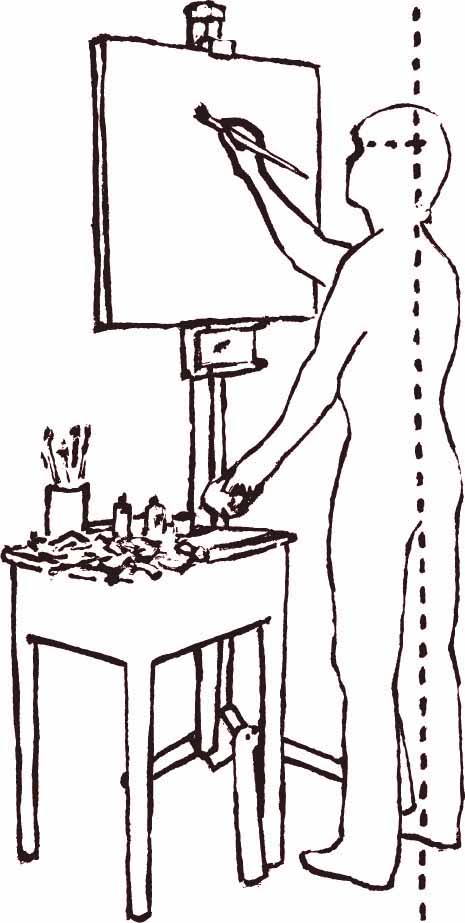

Here (see page 202) is a figure of a painter at work. She is somewhere in the outward, communal world that is implicitly represented by the sheet of paper on which the figure is printed. The outline of the figure is the self – what is hers; the area this outline encloses is her body. The heavier parts of the outline denote consciousness or the spirit, invested at the moment principally in the experience of working with hand and eye. Behind them, on a different plane to the flat of this sheet of paper, the painter’s mind is represented by a broken line. Before them, however, are tools and materials – the brush and paints – and the object she is working on.

How do these two models relate? Think about those tools first: they change what is outside the painter, and what is inside her. The brushstroke can be both more than she meant, and less than she meant. In referring to something, it alters it. That is the pleasure of using tools and materials – they surprise us by their difference from thought: that is their playfulness, their fun; that is the area of indeterminacy, of half-meaning, they share with the market-place/funfair.

The self, however, is the area of having and determining. We can compare it with the institution: it puts things in place and says exactly what they stand for. It is ‘sense’, in Frege’s terminology – a zone holding together the ‘reference’ made by the tools and establishing firm relations of communication and representation. Inside the self, or its visible shape – the body – lie the resources of the mind, brought into focus by the same spirit or conscious life that quickens the limbs. The mind, however, can seem to open out – in knowledge – beyond body and self. It may opt to contemplate the being of things, rather than closing around them in possession. It can become fascinated by them – like a viewer absorbed by the singularity of a painting within a museum, in the experience of ‘aesthesis’ discussed at the end of chapter 1. The mind can go beyond meaning, beyond representation, to reach for presence.

The painter at work (drawn by Julian Bell)

Beyond which, there is that which we cannot name – except that it is what we started with, whatever was outside us and outside the market. As soon as we say ‘object’, ‘reality’, ‘thing itself’, we have re-entered the arena of reference and hence representation, as we are bound to, on this side of the painting, the brush and the grave.

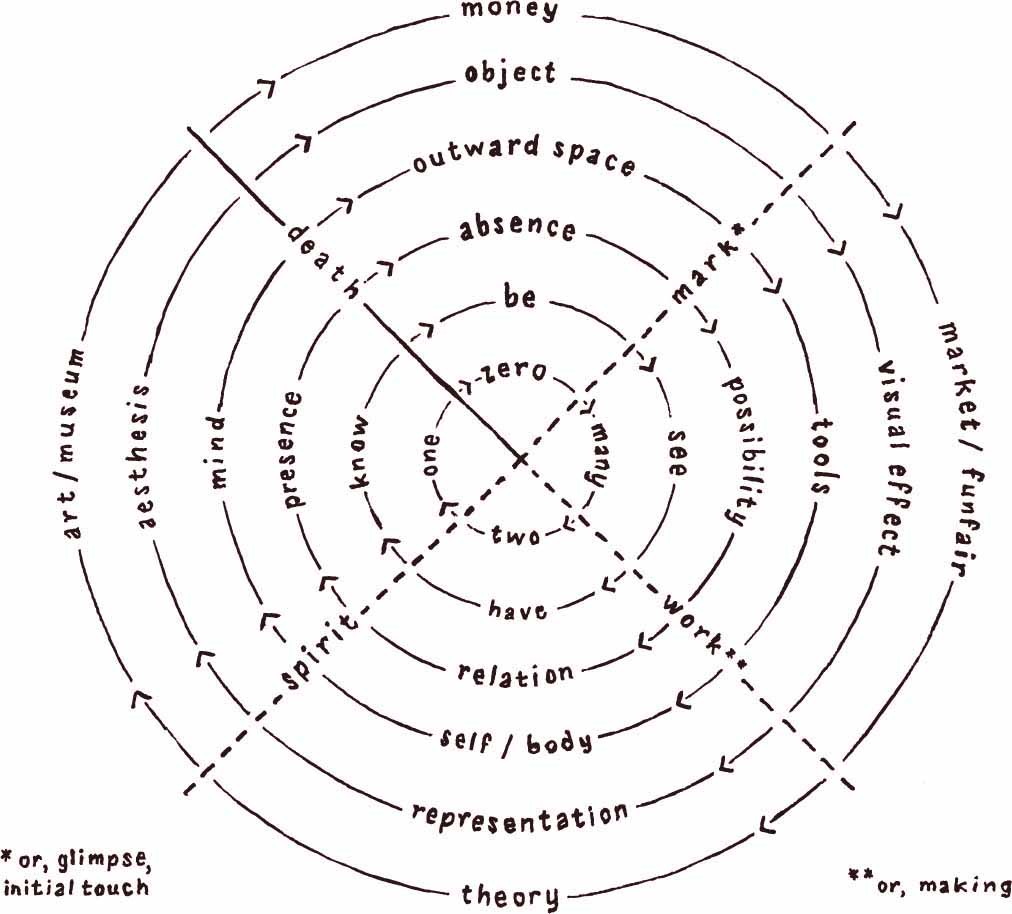

So there is a full circle of ways in which paintings exist. They are – since we have to use some word – ‘mere objects’, our prototype flat things; they are visual effects, of indefinite meaning; they are meaningful representations; they are sheer presence. And this fourfold quality applies equally whether we consider them psychologically, in relation to the individual, or socially, in relation to the economy within which they are made. Furthermore, there is a characteristic direction in which we move from one mode of attention to another. In fact the circle could be pictured as a wheel, driven by human desires and constructive intelligence, and moving through different levels of stimulus to complete its rotation at death. Adapting the terms of the foregoing argument, and expanding their implications, we could plot it out in the fashion of the diagram on page 204:

What this diagram proposes with regard to paintings, is that we cannot look at them in all ways at once. Yet no mode of attention can be cut adrift from the others: they are all interdependent. Intellectual fashion may enjoin us to regard a certain painting under a certain aspect at a certain time, but we need to get a measure of independence from intellectual fashion.

We need to do this because it allows us mobility in our own reactions to paintings. We are all prone to be nagged by the anxious question ‘Is this painting good?’; yet we all know that the good we get from a certain painting – the stimulus or pleasure it offers us – changes, and may indeed evaporate, as we grow. If some paintings are indeed ‘good’, this is simply to say that they dependably draw viewers in, to pursue this stimulating or pleasurable cycle of involvement, repeatedly through the viewers’ lifetimes; but we should not let the term shackle us to responses that are not our own.

As a byblow, this mobility of attitude opens out to us the possibility of enjoying writing about painting as a creative enjoyment in its own right. You don’t have to agree with art writers and theorists to read them with benefit: you just have to suspend disbelief, in order to relish an authorial voice. It sometimes seems that the finest art writing is best left unillustrated, so that the handsome conceptualizations of Alberti, Lessing, Baudelaire, Greenberg and so on are free to float off into some universe parallel to that inhabited by the pictures that initially gave them leave to talk.

This book, though, is meant as a picture book. Its illustrations are chosen with a hope to open out the world of painting, to point towards its diversity, rather than its unity. The vision of painting’s history to which these images refer is structured less like a tree than a bramble patch, with countless localized focuses. Very possibly there are painters today aligning themselves with every type of theoretical stance hinted at in this book, in every sort of combination of motives; certainly there will be countless more pursuing objectives this book has not even hinted at, and far more yet for whom the articulation of a rationale for painting is entirely irrelevant.

Painting’s compass (drawn by Julian Bell)

Painting is only a unity insofar as we need limits within which to talk. It extends and merges with other skills: out beyond the frame in every sort of adorning and useful work, from weaving to joinery, out before and behind in sculpture – arts addressed to the eye that this book has hardly touched on. Approaching such arts, painting approaches their comparative innocence of verbalization. Who needs a theory of firework displays?

One last picture. Its painter is uncertain: probably Grigory Soroka, a Russian serf trained under an academic master in the 1840s, who is said to have killed himself after being arrested for revolutionary activities at the age of forty-one. It is not important. Here we are brought within touching distance of that ‘object itself’, nature itself, of which we are part, looking back on itself, doubling itself, representing.

The talk takes place in another part of the room.

Grigory Soroka, Reflection in a Mirror, 1840s