“SHEEP ARE THE DUMBEST ANIMALS on God’s green earth,” our neighbor avowed, with a vigorous shake of his head when he saw the newest additions to our farmstead. His belief is not uncommon. In fact, sheep are love–hate animals: People either really love them or really hate them. And the people who really hate them love nothing more than to malign them.

But sheep don’t deserve the bad rap they’ve received. They fill a niche that needs filling: they provide economically efficient food and fiber, they eat many kinds of weeds that other livestock species won’t touch, they’re relatively inexpensive to begin raising, and they reproduce quickly so that a minimal capital outlay can yield a respectable flock in short order.

On top of all that, sheep are simply nice, gentle animals. Watching a group of young lambs charging wildly around the pasture or playing king of the hill on any mound of dirt, downed tree, or other object that happens to occupy space in their world has to be one of life’s greatest joys.

Admittedly, there are some difficulties to raising sheep: They think fences are puzzles that you’ve placed there for them to figure a way out of. Their flocking nature can sometimes make handling a challenge. Although they’re less susceptible to many diseases than other critters, they’re more troubled by parasites. They’re also vulnerable to predators. But with the help of this book, even a novice can learn to manage the negative aspects of raising sheep while enjoying the benefits.

Scientists consider sheep to be members of the family Bovidae, which includes mammals that have hollow horns and four stomachs (ruminants). All sheep are in the genus Ovis, and domestic sheep are classified as Ovis aries.

The human need for animals isn’t new: food, fiber, traction (the ability to do work, such as pulling, pushing, and carrying), and companionship led humans to domesticate animals more than 15,000 years ago. Dogs were the first animals to be domesticated, but humans bonded with sheep and goats early on as they settled into agriculturally based communities. Both sheep and goats were domesticated about 10,000 years ago, according to the latest theories.

Biologists believe that modern sheep are descended primarily from the wild Mouflon sheep of western Asia, although other wild sheep (for instance, the Urial of central Asia) may have been mixed in since domestication took place. Some breeds, such as the Soay of Europe, still retain many of the characteristics of their wild ancestors, but most modern breeds have changed substantially. Traits of wild sheep include naturally short, fat tails; coarse, hairy outer coats; short, woolly undercoats; and great curling horns on the rams. Wild sheep are endangered or threatened throughout the world.

The last several decades have not been especially kind to the North American sheep industry. The total number of sheep has continued to fall: in 1995 there were over 10 million head; as I write this in 2008, the number is just over 6 million. Considering that around the middle of the twentieth century there were over 50 million head in the United States, this decline seems especially disheartening. The numbers of U.S. farms that report having sheep hit bottom in 2004; since then there has been a slight increase in farm numbers, with the growth largely reflecting more small-scale producers who keep 25 or fewer breeding ewes, while the number of commodity-scale producers (large-scale sheep operators who keep hundreds or even thousands of breeding ewes) continues to fall.

In spite of the increase in smaller flocks, however, most sheep still come from the largest operators, primarily in the western states and in the western provinces of Canada. According to the “Sheep Industry Economic Impact Analysis,” a report prepared for the American Sheep Industry Association by Dr. Julie Stepank Shiflett in 2008, “About 2 percent of sheep operations account for one-half of sheep and lamb production in the United States.” Yet small flocks and shepherds will be better able to respond to changes in the marketplace in coming years.

Globalization obviously has a lot to do with the seemingly endless downward spiral of our sheep industry: most lamb in the grocery store and offered on the menu at restaurants comes from foreign sources (New Zealand and Australia are the top two exporters of lamb to the United States). But I’m ever the optimist, and there are some factors that seem to suggest better times ahead for shepherds.

Historically, wool was a major, driving force in the sheep industry, but as synthetic fibers replaced wool in most of its traditional uses and warehouses around the world became clogged with surpluses, domestic producers began focusing more on lamb and mutton production for the meat market. Those who are able to direct-market their lamb especially are seeing fairly high returns for their efforts. A growing number of producers are also pursuing sheep for truly alternative markets — raising dairy ewes for the production of sheep’s-milk cheeses, using sheep in land management for their excellent weed-and-brush-control abilities, or raising and marketing pet sheep. And a small yet dedicated number of producers still focus on wool production as their primary emphasis, but many of these concentrate on producing high-quality fiber for the handspinning and specialty-wool markets, which are actually seeing a renaissance as unprecedented numbers of women and men are committed to taking up the time-honored skills of knitting, spinning, and weaving.

One particularly bright spot, in my opinion, is the increased awareness of consumers who ask, How was this animal raised, how was it handled and processed, where is it from, or was child or slave labor used? These educated consumers still want to eat lamb (or wear wool), but they also want to be assured that their purchasing choices reflect their personal values. They care about the state of the environment and the humane treatment of animals; they support family farmers as integral members of our society who help maintain our countryside with the “rural character” most of us recognize as important. They care about the aesthetic qualities of farmland viewscapes and the wildlife, water quality, air quality, and other keystones of sustainability that a vibrant and healthy rural place embodies. In fact, consumers have shown time and again that they are willing to put their money where their mouths are. The Slow Food movement, the Locavore movement, the grassfed movement (see Resources for Web site addresses), and the exponential growth of the organic marketplace in recent years all demonstrate the heightened awareness among consumers of the social and ecological issues that surround the food we eat.

Country of Origin Labeling, or COOL, is another exciting development for U.S. shepherds: included in the 2002 and 2008 farm bills, COOL became mandatory on September 30, 2008. It requires retailers to notify their customers of the country of origin of the lamb and mutton they sell (as well as to provide notification on a number of other commodity products, including beef, pork, chicken, goat, fish, and shellfish, and perishable agricultural commodities and nuts). The implementation of mandatory COOL is expected to boost domestic sales of American-raised commodities dramatically, and I think it will be particularly beneficial for the sheep industry — not only shepherds, but also the myriad support industries that are crucial for getting their products to consumers. For example, the “Sheep Industry Economic Impact Analysis” report shows that “for every dollar of lamb, mutton, wool or sheep’s milk produced, an additional $2.55 is generated that supports linked industries and jobs in this country.”

Like consumers, restaurateurs and chefs, through organizations such as the Chefs Collaborative, are using their voices to advocate for family-farm producers of sustainably and humanely raised meats, and they are showing increased interest in lamb. A recent study by the American Lamb Board indicates that increasing numbers of chain restaurants are offering lamb and that almost three-quarters of the high-profile, white-tablecloth restaurants regularly offer lamb on their menus.

Global-energy economics are changing rapidly, and as the cost of shipping products from foreign ports to North America increases, the economic situation for producers here will most certainly improve. This change will particularly benefit the commodity producers, who have challenges direct marketing their lamb to consumers or chefs. And as the green building movement continues to expand, environmentally friendly uses of wool, such as in insulation and bedding, will also help provide more markets for wool.

Vertical integration occurs when large multinational companies begin controlling all facets of production and marketing, though some small-scale producers successfully use the concept of vertical integration in their own operations, producing not just lamb or wool but also consumer-ready products, such as specialty processed meats and sweaters.

Typically, when a market segment becomes vertically integrated, it’s very hard for small producers to exist in that segment. The poultry and pork industries are good examples. The sheep industry, on the other hand, hasn’t been taken over by corporate giants, so small producers who can produce by using low-cost methods can still remain in the black. In fact, if you’re willing to market your own product, you can do quite well.

Sheep are especially good animals for small-property owners who don’t have the space to raise cattle but want some kind of livestock. Five to seven ewes and their offspring can typically be run on the same amount of land as only one cow and a calf. Sheep can graze lawns, ditches, woodlots, and orchards (with full-size trees only — the sheep will eat dwarf trees if you plant them).

Starting small gives you the opportunity to gain low-cost experience. If you start with fewer sheep than your land will support (see chapter 3), you will be able to keep your best ewe lamb each year, for a few years at least. After a while, as your purchased ewes become unproductive, they can be replaced with some of your best lambs.

Although a homesteader may occasionally sell a few lambs or fleece, normally the flock is raised primarily for personal use. Providing your own meat and some fleece for handspinning and for a 4-H project for the kids are among the reasons homesteaders choose to keep a few sheep. Typically, these flocks are small, usually no more than a dozen ewes and a ram.

Commercial flocks vary in size from fairly small flocks of 20 to 50 ewes to vast flocks that number in the thousands. Today, more than 80 percent of the sheep raised in the United States are raised in large “range bands” in the western half of the country. These bands typically have 1,000 to 1,500 ewes and are tended by one or two full-time shepherds and their dogs.

The main factor to consider is that for commercial flocks — even relatively small ones — marketing must be vigorous. This can be direct marketing to consumers or marketing through the conventional commodity system of sale barns and middlemen, but to do it profitably, it’s going to take time, energy, and thought (see chapter 11).

More than one commercial flock has grown out of a homestead flock. Suddenly, a flock that began with one or two ewes grows to 20 or 30, and the homesteader is looking for a larger piece of land or some additional places to graze the sheep on other people’s land.

Then there are folks who jump from virtually no experience with sheep to acquiring a commercial flock in one step. Perhaps they’ve inherited a farm or have decided to purchase their dream farm. These folks face a greater challenge than those who take the “grow-your-own-flock” approach, but the rest of this book should help either type of new shepherd.

There are two approaches to any type of agricultural enterprise: the high-input, intensive system and the low-input, extensive system. The high-input system is the one that currently dominates U.S. agriculture. This system requires tremendous inputs of labor and cash for fertilizers, pesticides, harvested feeds, veterinary services, extensive lines of machinery, and specialized buildings. Farmers practicing high-input, intensive agriculture hope to generate enough product to meet those costs and make a profit regardless of what “the markets” are doing. In the intensive system, there is an expectation that more lambs mean more money, but that isn’t always the case. Although the intensive approach works for some folks, there are far more who are drowning in worthless products and piles of bills.

The low-input, extensive management system places far less emphasis on production volume and more on profitability. This is also the system that’s been tagged “sustainable agriculture” in recent years. Sustainable practitioners look to maximize profit while protecting the environment and the social structure of their rural communities. They consider quality of life to be as important as gross income, but they would probably agree that net income plays a big role in having a good quality of life.

In this system, farmers try to mimic nature — for example, by lambing in the spring when the grass is coming on (and wild animals are having their young). They look to their animals to carry a fair share of the workload, harvesting their own feed and spreading their own manure for a large portion of the year. Successful practitioners of low-input, extensive agriculture find that both labor and costs are dramatically reduced. The time they save allows them to maximize profits by working on direct marketing. This book emphasizes the low-input, extensive system because this type of management is especially well suited to homestead flocks and small commercial producers.

The sheep production systems currently in use are these:

Accelerated lambing. The most intensive approach to sheep production, accelerated lambing calls for each ewe to lamb at least three times every two years. This system requires a high outlay of capital for lambing barns and feedlots or barns (finishing facilities). It requires sheep that have the genetic capability of lambing more than once a year and phenomenally good management with excellent nutrition to keep the ewes healthy enough to do so.

Accelerated lambing. The most intensive approach to sheep production, accelerated lambing calls for each ewe to lamb at least three times every two years. This system requires a high outlay of capital for lambing barns and feedlots or barns (finishing facilities). It requires sheep that have the genetic capability of lambing more than once a year and phenomenally good management with excellent nutrition to keep the ewes healthy enough to do so.

Winter-confinement lambing. In this intensive system, lambing occurs in January and February in lambing barns. Lambs are able to nurse and self-feed in creep feeders, which allow the lambs free-choice access to extra feed but prevent the ewes from getting at the self-feeders. After weaning, usually around 2 months of age, the lambs are kept on free-choice feed in finishing facilities until marketing time.

Winter-confinement lambing. In this intensive system, lambing occurs in January and February in lambing barns. Lambs are able to nurse and self-feed in creep feeders, which allow the lambs free-choice access to extra feed but prevent the ewes from getting at the self-feeders. After weaning, usually around 2 months of age, the lambs are kept on free-choice feed in finishing facilities until marketing time.

Phase lambing. Another highly intensive approach, phase lambing seeks to have the ewes lamb only once a year, but the flock is broken into three or four groups. This allows lambing throughout the year, so lambs can be marketed throughout the year. It requires capital outlay for building and feeding facilities, but these can be somewhat smaller than those required for accelerated lambing or winter-confinement lambing, because only part of the flock is lambing in any given season.

Phase lambing. Another highly intensive approach, phase lambing seeks to have the ewes lamb only once a year, but the flock is broken into three or four groups. This allows lambing throughout the year, so lambs can be marketed throughout the year. It requires capital outlay for building and feeding facilities, but these can be somewhat smaller than those required for accelerated lambing or winter-confinement lambing, because only part of the flock is lambing in any given season.

Early-spring-confinement lambing. With March and April lambing, the lambs must be lambed in a barn but are often finished after weaning on high-quality pastures instead of in finishing facilities. This system is an intensive-extensive hybrid.

Early-spring-confinement lambing. With March and April lambing, the lambs must be lambed in a barn but are often finished after weaning on high-quality pastures instead of in finishing facilities. This system is an intensive-extensive hybrid.

Fall lambing. Like early-spring-confinement lambing, this system is a hybrid of intensive and extensive systems, but capital outlay is for finishing facilities instead of lambing barns.

Fall lambing. Like early-spring-confinement lambing, this system is a hybrid of intensive and extensive systems, but capital outlay is for finishing facilities instead of lambing barns.

Late-spring pasture lambing. This is the most extensive system. Few facilities are required, and less labor is required than in the other approaches because lambs drop and finish on pasture.

Late-spring pasture lambing. This is the most extensive system. Few facilities are required, and less labor is required than in the other approaches because lambs drop and finish on pasture.

Some readers may be interested in organic production. There are some successful organic producers in the sheep business, although internal parasites can challenge those producers who want to be “certified organic,” because such certification prohibits the use of most commercial worming medications. Most organic producers are practicing grassfed production (see page 11), as animal health is easier to maintain where the animals are never kept in confinement. But not all pasture-raised animals automatically meet the stringent standards for organic certification.

Consider the following if you want to pursue certified organic production:

Record keeping is significant, as producers must work with third-party certifiers to ensure that they are indeed meeting all the requirements of the organic standards adopted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). They must thoroughly document that their farm, feed, and health care practices are in compliance with the standards. They must maintain identification of all animals sold for slaughter, as well as breeding stock, throughout their lives.

Record keeping is significant, as producers must work with third-party certifiers to ensure that they are indeed meeting all the requirements of the organic standards adopted by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). They must thoroughly document that their farm, feed, and health care practices are in compliance with the standards. They must maintain identification of all animals sold for slaughter, as well as breeding stock, throughout their lives.

The organic standards specify a wide array of conditions under which organically raised livestock must be maintained. For example, they must have access to pasture, though temporary confinement is allowed if it can be justified due to inclement weather, stage of production, or situations where the animals’ health and safety are in jeopardy.

The organic standards specify a wide array of conditions under which organically raised livestock must be maintained. For example, they must have access to pasture, though temporary confinement is allowed if it can be justified due to inclement weather, stage of production, or situations where the animals’ health and safety are in jeopardy.

All feed, whether raised on the farm or purchased, must be certified organic and cannot contain synthetic hormones, medications, or other restricted materials. Pastures and croplands that provide food for the animals must be maintained without the use of pesticides, herbicides, chemical fertilizers, or other restricted materials. Even bedding has to be certified organic.

All feed, whether raised on the farm or purchased, must be certified organic and cannot contain synthetic hormones, medications, or other restricted materials. Pastures and croplands that provide food for the animals must be maintained without the use of pesticides, herbicides, chemical fertilizers, or other restricted materials. Even bedding has to be certified organic.

During processing, your organic meat cannot come into contact with someone else’s nonorganic meat, which means your slaughterhouse will have to be set up so that it can accommodate organic animals. During the processing of meat products, such as sausage, you cannot use preservatives or any kind of artificial flavoring agents.

During processing, your organic meat cannot come into contact with someone else’s nonorganic meat, which means your slaughterhouse will have to be set up so that it can accommodate organic animals. During the processing of meat products, such as sausage, you cannot use preservatives or any kind of artificial flavoring agents.

Health issues are far more challenging under organic standards: Animals may receive vaccinations, but beyond that there are strict limitations on the use of any medications, including anthelmintic drugs. Those being raised for slaughter cannot be treated with any antibiotics, anthelmintics, growth implants, or other prohibited materials. Breeding stock may be dewormed during the first two-thirds of gestation with Ivermectin on the basis of actual fecal-egg-count tests documenting that the treatment is necessary — in other words, animals can’t be treated on a routine preventive schedule — but because there is a 90-day withdrawal period, and no lamb can nurse during that period, it just about eliminates the possibility of using Ivermectin even on your breeding stock. If in doubt, your organic certifier can help clarify when you might be able to use it safely for breeding animals.

Health issues are far more challenging under organic standards: Animals may receive vaccinations, but beyond that there are strict limitations on the use of any medications, including anthelmintic drugs. Those being raised for slaughter cannot be treated with any antibiotics, anthelmintics, growth implants, or other prohibited materials. Breeding stock may be dewormed during the first two-thirds of gestation with Ivermectin on the basis of actual fecal-egg-count tests documenting that the treatment is necessary — in other words, animals can’t be treated on a routine preventive schedule — but because there is a 90-day withdrawal period, and no lamb can nurse during that period, it just about eliminates the possibility of using Ivermectin even on your breeding stock. If in doubt, your organic certifier can help clarify when you might be able to use it safely for breeding animals.

In spite of the challenges, if you are able to produce and market organic lamb, you will get premium pricing for your product. Chapter 11 discusses products and marketing and will help you evaluate the costs and benefits of becoming certifiably organic.

For several decades there has been a movement among sustainable farmers to produce meat (and other animal products, such as milk) strictly off grass, and now consumers have begun to recognize not only that grassfed meat is more nutritious than meat from animals raised in confinement and fed a grain diet but that it is also the product of better environmental practices.

One of the major forces behind the push for recognition of the health benefits of grassfed meat is Jo Robinson, an investigative journalist from Washington state. Jo told me that one day in 1985, while she was researching omega-3 fatty acids, she came across an intriguing study. It found that animals in the wild had much higher levels of omega-3s than farm-raised animals, because they are browsers that eat mainly grasses and bush. Not long after, she read that meat from farm animals raised on pasture and grass had values of omega-3s that were very close to wild meat. She followed that thread, spending much of the next decade continuing to research the topic — though it wasn’t easy.

“It took me years to research all the benefits of grassfed meat, dairy products, and eggs,” Jo said, “because at that time there was very little research in the United States. We had totally committed our national agriculture to confined, grain-fed animal production, so that’s what all the research was on. I had to go back to studies done prior to the 1970s in the U.S. research literature, and to European and New Zealand studies for more modern research. But gradually I pieced together all these studies and discovered that grassfed was better for the health of the animals, better for the health of consumers, better for the environment, and better for the farmers, partly because they could earn more money marketing directly to consumers. Grassfed is small and local — there aren’t any grass-based megafarms — so you are feeding local economies when you eat grassfed.”

As her research continued, Jo discovered that grassfed animals don’t just benefit from higher levels of omega-3s (two to five times higher than in animals raised in confinement and fed largely grain-based diets). They also boast higher levels of other beneficial nutrients: Conjugated linoleic acid (CLA), another good fat, is also two to five times higher in grassfed meat and dairy products than in those from grain-fed animals. Antioxidants (the nutrients that help fight the free radicals that attack our cells, leading to cancer and other ailments) are 10 to 50 times higher. And grassfed products contain significantly higher amounts of vitamins, minerals, calcium, and even dietary fiber.

Today Jo runs a great Web site for consumers and farmers that helps connect grassfed producers with customers. See Eat Wild in the general information section of the appendix and Jo’s books in the book section of the appendix. Also check out the American Grassfed Association (AGA), listed in the same section, for more information on grassfed production standards and labeling and marketing of grassfed products. There are USDA standards for grassfed labeling, and the AGA is currently working on its own third-party-verified system for grassfed labeling that is even stricter than the USDA standard, which allows animals to be kept in confinement if they are fed silage.

When you decide to get sheep, it helps if you understand their behavior — in other words, what makes them tick. The more you understand about their behavior, the easier it will be for you to spot problems (for example, is that ewe in the corner sick or is she about to lamb?). Understanding behavior also makes handling animals much easier, on both you and them.

Behavior can be thought of simply as the way an individual animal, or a group of animals, responds to its environment. Behavior falls into three main categories: normal, abnormal, and learned. Remember, in the case of sheep, most of their behavior stems from their position in the food chain: they are prey animals — as such, they are rather small and vulnerable.

Sheep that are behaving normally are content and alert. They have good appetites and bright eyes. They are gregarious animals, which contributes to their flocking nature. Youngsters, like those of other species, love to play and roughhouse. Groups of lambs will run, jump, and climb for hours when they are healthy and happy. Then they’ll fall asleep so deeply that you may think they’re dead.

Sheep learn to adapt to new environments or new conditions within their environment. With patience and the right cues, you can teach them to move into handling facilities or through gates and into new pastures. Through “punishments,” they can quickly learn to avoid certain things, like an electric fence.

Abnormal behavior usually is related to either stress or disease and can take many forms, such as wool eating, fighting and other aggressive actions, lack of appetite, excessive “talking,” and sexual nonperformance. Stress-related abnormal behavior most often occurs in the close confinement of intensive production systems; these abnormal behaviors rarely occur in animals that are raised in an extensive, pasture-based system. If left unchecked, the stress that contributes to abnormal behaviors creates an environment in which disease can get a strong foothold. It’s best to eliminate or minimize stress-causing agents on your farm. See chapter 3 for what you can do to relieve stress through pasture, fence, and facility design.

Although all sheep are generally considered to be gregarious, there are always differences among breeds and differences among individuals. Relationships are generally strongest between animals of the same species, although animals can learn to have a relationship with animals of other species (for example, you, your horses or cows, your dogs). Relationships also tend to be strongest between members of the same breed. Oftentimes, if two distinct breeds are run in the same large pasture, they’ll group together in two distinct flocks that avoid each other’s space. Within a flock, relationships tend to be strongest among family units. An older ewe, her children, her children’s children, and so on will behave as a unit.

Like most prey species that join together as a group, a sheep flock has a pecking order, or dominance hierarchy. On pasture, dominant and subordinate relationships don’t tend to have much impact on any members of the flock, but they can be important if the sheep are fed in a confinement system. Animals at the top of the pecking order will “hog” the feed at a trough, and animals at the bottom will starve.

Dominant animals are simply the more aggressive members of the group. This aggressiveness may be the result of age, size, sex, or early experiences. The dominant ewe within a flock will have dominant daughters, but I don’t know if this is as much an inherited trait as a learned position.

Dominance among rams just before and during the breeding season is easy to observe, as they actively fight for the top position in the pecking order. Rams fight by backing up and then, with heads down, charging forward at a full run to butt heads. This type of fighting generally ends when one ram backs down, but rams can be seriously injured or killed during these fights.

Leader-follower relationships are strong in sheep. Interestingly, the leader of the flock may not be its most dominant member. Because of the stronger relationships among family members, the oldest ewe with the largest number of offspring often becomes the leader of the flock.

If behavior is thought of as being the way animals react to their environment, then senses are the tools they use to investigate their environment and emotions are the outward manifestations of this reaction. Let’s talk about emotions first.

Sheep, like other mammals, are capable of displaying a full array of emotions, from anger to happiness to the most common emotion we humans see when dealing with animals: fear. Scientists have discovered that fear memories are stored in a primitive part of the brain; consequently, these memories stay with an animal for long periods. If an animal has an especially bad fright, for example, upon entering a barn, it will continue to fear entering that building. (See chapter 3 for more about handling facilities.)

As much as fear reactions can be a pain in the neck for shepherds, remember that those reactions are genetically programmed in sheep to ensure their survival. Sheep are prey animals, and the speed with which they have a fear reaction is part of their defense against predators — and make no mistake about it: when sheep see you, they see a predator. With patience and training, however, you can win their trust.

Like humans, sheep count on their senses for understanding the world around them. And as prey animals, they rely heavily on their sense of sight. A sheep’s eyes are set off to the sides of its head, creating a wide field of vision (between 270 and 320 degrees, depending on how much wool it’s wearing). This wide field of vision allows it to see predators at great distances — and, more important, in almost any direction that a predator may approach. Sheep do have a blind spot directly behind them, so if you are approaching from the back, make sure to let them know you’re there by talking to them.

Sheep have a fairly wide field of mono-focal vision and a small area of bifocal vision. They also have blind spots directly in front and in back of their bodies. When sheep are sheared, they can see everything between points 1 and points A on either side of their bodies. As their fleece grows out, they see less toward the back but can still see everything between points 1 and points B.

They also have a small area of bifocal vision directly in front of their noses. This bifocal vision allows them to focus on an item with both eyes at the same time and greatly enhances depth perception. This is why you’ll sometimes spot a sheep staring at something right in front of its nose with great intensity: it’s bringing the item into focus with both eyes. Scientists believe that sheep have keen vision and that they see and can differentiate among colors.

After sight, hearing is probably the most important of the sheep’s senses. Sheep hear at a much higher frequency of sound than you do. Low-pitched rumbling sounds won’t really disturb them, but any kind of high-pitched sound, like that of a human yelling, will send them off the deep end. Very loud or novel sounds will also cause stress. On the other hand, with training, your sheep can learn that certain loud sounds have meaning, like a whistle that signals it’s time to come for food. Ewes and lambs can hear, and differentiate between, the voices of their offspring or mother over fairly long distances. An animal that is separated from the flock will call incessantly to try to locate its buddies. One interesting fact about the sheep’s auditory system is that it can pinpoint where subtle sounds are coming from by “tuning in” its two ears separately.

The sense of smell is extremely important to sheep, and it’s much stronger than a human’s. Smell is the first sense that ewes use to identify their lambs at birth and while they are nursing. The ewe recognizes her own scent from the amniotic fluid that is coating the lamb and later from the milk odor. One method of grafting an orphan lamb to a ewe is to fool her sense of smell by rubbing down the orphan with her amniotic fluid. Rams also use the sense of smell to detect ewes that are coming into heat or are ready to mate; at that time, females release a chemical pheromone, which is like a perfume, which the male smells.

Taste and touch are the least important senses. Sheep use taste the same way humans use it: to decide if something is good to eat. Touch is used in courting, in parental bonding, and sometimes to become more familiar with something. Unlike humans, however, a sheep does most of its touching with its nose. You’ll often see this behavior if something new has been introduced to the animal’s environment: first, it approaches with its neck stretched far out while it sniffs the air; then it touches the item with its nose.

When you are working a flock of sheep (for example, for moving or shearing), it helps to have patience, to move slowly, and to work quietly. Working your animals is always stressful on them, so your efforts to reduce their stress will pay dividends in better production, less illness, and fewer injuries. If you’re working sheep within the first month after they’ve been bred, stress can actually cause abortion. Your patience and slow, quiet approach will not only reduce the stress on them but reduce yours as well.

Moving and controlling flocks in large areas are often best accomplished with the assistance of a herding dog. Chapter 4 discusses the use of these working companions. Working your flock also becomes easier if you use good handling facilities such as catch pens, chutes, and gates. Read more about these in chapter 3.

A breed of animals is a group that has been raised to exhibit similar, inheritable traits. Most breeds have a breed association or registry that establishes the standards for the breed and maintains records of “registered” breeding stock. A purebred possesses the distinct characteristics of the breed and is registered, or eligible for registration, with the breed association.

The advantages of purebreds are greater uniformity in appearance and production and a chance of income from the sale of breeding stock, although in most cases the additional cost associated with maintaining and marketing purebred animals isn’t offset by the extra income. If you or your children are interested in showing sheep, then purebreds offer a much wider array of show opportunities. The disadvantages are the higher initial expense and the costs of registering lambs, with no better price for wool or meat.

Different breeds were developed in response to market needs and the conditions under which the animals were to be raised. For example, some breeds were raised to flourish in hotter climates and others in cool climates. Some breeds have a higher incidence of multiple births (which is fine if you are able to give them sufficient attention to ensure survival and good growth), and some breeds are able to lamb more than once a year (this is known as “out-of-season” lambing).

Crossbred sheep are those that have blood from one or more breeds in their lineage. Crossbreeds often produce as well as, if not better than, purebreds as a result of a phenomenon known as hybrid vigor. Although purebreds usually exhibit certain desirable traits, inbreeding can also bring out some undesirable traits; when sheep of two different breeds are bred to each other, the most desirable traits of each breed tend to come out and the less desirable ones don’t. This makes for hardier, more vigorous, and more productive offspring — hence the term “hybrid vigor.”

Most commercial flock owners run a crossbred flock for their production animals, though many also maintain smaller, registered flocks. A typical cross in commercial circles is a ewe with one-half Finn and one-half Rambouillet blood; these crossbred ewes are typically bred to a Dorset ram, yielding one-quarter Finn, one-quarter Rambouillet, and one-half Dorset lambs. See chapter 2 for help deciding which breed, or crossbreed, might be best for you.

In the areas of the country where sheep are raised most commonly, some sheep are classified as native and some as western, or range, sheep. In reality these terms have little significance to you as a shepherd, but you may hear people use them from time to time. The terms don’t necessarily refer to a specific breed — or even a specific cross — but they refer to a “type.” Native sheep are raised primarily for meat and are large, prolific, and usually black faced. Western sheep are usually fine-wool sheep or are a cross of fine-wool and long-wool breeds. Fine-wool sheep were often preferred on the western ranges, not for their wool but for their strong flocking instinct.

If you are new to sheep, then read the rest of this book before purchasing your first sheep. Studying before buying will save you money, time, aggravation, and possibly the lives of your sheep! But if you are ready to buy, here are some things to keep in mind.

Unless you plan to have only a few sheep, try to obtain ewes with similar breeding for your first foray into shepherding. Not only will these ewes share traits such as temperament, breeding period, gestation period, and maturity dates, they’ll also produce lambs of similar quality that mature at about the same time, which will enhance the marketability of your lambs.

If you don’t have a preference for a particular breed, consider the predominant one in your area. It’s likely to be well suited to the climate, and buying close to home cuts down on shipping costs and a stressful ride for the animals.

You can get replacement rams more easily, even trading with other breeders nearby, after you have used yours for a while and want to avoid inbreeding.

Until you become an experienced shepherd, it may be best to seek a mentor who can help evaluate the animals before you buy. Another shepherd, or a veterinarian, can help you evaluate the conformation and general health of the animals you’re considering, and paying for such a consultation actually can save lots of money down the road.

If you’re considering buying sheep, think seriously about the timing of your purchase. It’s best to buy at a period when the animals aren’t going to have to do anything too significant right after they arrive on your farm. Moving to a new home is as unpleasant for them as it is for you, and they take some time to settle in.

Your first purchases should be directly from a farmer or rancher who raises sheep. (These sales between individuals are called private-treaty sales.) If you’re buying purebred stock, the breed association can help identify shepherds in your region who raise the breed that interests you. If you don’t have your heart set on a specific breed, ask around for references to a reputable farmer. Veterinarians, county Extension agents, and other small-flock owners may be able to give you some names of shepherds to talk to.

Don’t buy from the first farmer you visit; try to check out two or three farms. Look around at each, but don’t judge on the “fanciness” of the facilities. Some excellent shepherds (especially if they’re full-time farmers) have old, unpainted buildings but still have excellent, healthy animals, and that’s what you’re there for! Although the facilities may be old and in need of a coat of paint, they should be fairly clean. This doesn’t mean that there will not be any manure piles around or any equipment stuck in a corner, but it does mean that bottles of medicine, bags of chemicals, used needles, and just plain trash shouldn’t be in evidence anywhere you look. If it’s been raining or snowing for a while, the ground may be muddy, but the sheep should never be chest deep in wet manure or mud.

At each farm, ask the shepherds about their breeding plans:

What are they trying to accomplish with their flocks?

What are they trying to accomplish with their flocks?

Do they have production records and health records on the flock?

Do they have production records and health records on the flock?

Will they provide a five-day health warranty? Some farmers won’t do this, and with good reason: they don’t know how you will take care of the animals. But many will stand behind their animals’ health for a short period.

Will they provide a five-day health warranty? Some farmers won’t do this, and with good reason: they don’t know how you will take care of the animals. But many will stand behind their animals’ health for a short period.

Will they deliver your animals? Within a reasonable distance, this may be part of the sale price, but for long distances, expect to pay farmers for trucking.

Will they deliver your animals? Within a reasonable distance, this may be part of the sale price, but for long distances, expect to pay farmers for trucking.

Will they provide some technical support after purchase, like answering phone questions?

Will they provide some technical support after purchase, like answering phone questions?

If a seller seems unwilling to answer your questions or is impatient with you, go somewhere else.

Don’t purchase your first sheep at the sale barn or livestock auction house. Although some good ewes may go through there from time to time, it’s the most dangerous way for beginners to purchase their animals. First, even if the animals are healthy when they get there, they’re exposed to all kinds of other animals that are there specifically because they aren’t healthy. Second, as a neophyte, you probably don’t have the ability to distinguish good, healthy animals from those that aren’t, especially at a distance as they run through the ring. If you do have a sale barn nearby, though, go there for educational purposes. Talk with the farmers and study the pricing of terminal market animals (those that are going for butcher). If you see some sheep that look good to your untrained eye, ask whose farm they come from, and by all means give that person a call.

Also try to move animals during mild weather, if possible, and avoid rough handling and overcrowding in transport. All animals become stressed by moving, but the worse the stress, the more likely they’ll come down with shipping fever, which can run the gamut from a small nuisance to a calamity.

The age of the sheep is important in relation to the asking price. Fine, young ewes that have already lambed once or twice usually bring the most money; they’re already proven breeders, but they still have lots of years, and lambs, ahead of them. But don’t rule out older sheep if you’re on a tight budget. You can get started with the least outlay of capital by purchasing someone else’s culls.

Commercial shepherds often cull ewes at 7 or 8 years of age, although their expected productive life is 10 or 12 years. And older ewes are often the previous owner’s better ewes, to have remained in the flock for a long time. Their years may be numbered, but with good care, older ewes can be even better for you than they were for their former owner because they don’t have to compete with younger ewes. By keeping the very best ewe lambs produced by these old ladies, you’ll soon have a nice young flock at a reasonable price.

When trying to decide on a fair price for someone else’s culls, ask yourself:

Just how much more fleece and how many lambs could this ewe be expected to produce?

Just how much more fleece and how many lambs could this ewe be expected to produce?

If she is quite old, how much additional and higher-quality feed will she need to compensate for her poor teeth?

If she is quite old, how much additional and higher-quality feed will she need to compensate for her poor teeth?

Does she have a history of twins and triplets?

Does she have a history of twins and triplets?

Let your offer reflect these conditions.

The opposite age extreme — baby lambs — may also provide a cheaper route to starting out with sheep. Oftentimes, shepherds who have a bunch of bummer lambs (orphans or rejected lambs that have to be hand raised on a bottle) are glad to get rid of some. But before you think of traveling down this path, you need to understand that bummers got that name for a reason: until they are weaned, feeding them is very time consuming. But if you have the time, it can also be very rewarding, and your hand-raised lambs will be close pets for life, running to greet you whenever you enter the pasture or barn. For more about feeding bummers, see chapter 10.

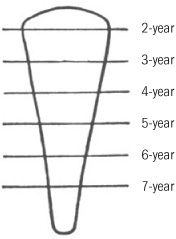

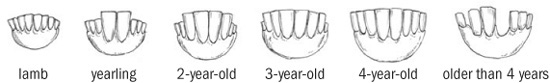

Sheep have no teeth in the front of the top jaw, though they do have 12 molars in the rear of the top jaw. They also have a hard palate, or dental pad, on top. Their bottom teeth consist of 8 incisors in the front and 24 molars, or cheek teeth, in the rear of the mouth. Up to a certain age, the incisors can help you figure out a sheep’s age.

A lamb has eight small incisor teeth until it reaches approximately 1 year of age. Each year thereafter, one pair of lamb teeth is replaced by two permanent teeth, starting with the inner two, that are noticeably larger. By the time the sheep is about 4 years old, all of its lamb teeth have been replaced by permanent teeth. After this point, it is no longer possible to accurately determine an animal’s age by its teeth, although you can make estimates based on the condition of the teeth. It will also begin losing permanent teeth at this point — hence the term “broken mouth.”

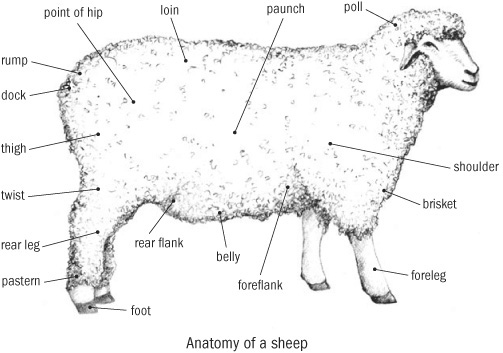

All that grinding action begins to wear down the sheep’s teeth, shortening its useful life and thereby its lifetime. As the incisors wear down, the amount of tooth below the gum line (about ½ inch [1.3 cm]) is gradually pushed out to help compensate for the wear. This is partly why the teeth of an older ewe look so much narrower — the wider part at the top of the tooth is being worn back toward the narrower center part of the tooth while the even narrower part below the gum line is being pushed up. With narrowing, gaps that reduce the efficiency of the ewe’s bite occur between the teeth. If you listen to an old ewe grazing, you can hear sound as the grass slips between her teeth.

On very short or overstocked pasture, the wear is faster, because sand and soil particles that are picked up as the animal grazes act like sandpaper on the teeth. The closer to the soil sheep graze, the more dirt and sand they ingest. On short pasture, ewes must take more bites to get a pound of grass, and each bite contributes to the wear of their teeth.

Approximate annual wear of sheep’s teeth

To some extent, you can determine the age of sheep by their teeth. In the front bottom jaw, they have four pairs of incisor teeth — all small baby teeth that, like human baby teeth, fall out to make way for permanent teeth. At about 1 year, the center pair falls out and the first pair of larger, permanent incisors appears. For each year until the sheep is 4 years old, it loses one pair of baby teeth and gains one pair of permanent teeth. After a sheep turns 4 years old, you can’t really tell its age by looking at the teeth.

In livestock terminology the word conformation means the shape and size of an individual animal compared with the ideal. Animals with good conformation are more likely to produce well, although we’ve had a few critters over the years that were pretty ugly by conformation standards but still did fine, so don’t obsess about perfect conformation.

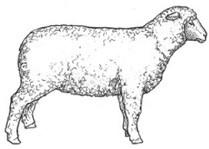

WHEN YOU’RE SHOPPING FOR SHEEP, CHOOSE ANIMALS THAT HAVE GOOD CONFORMATION

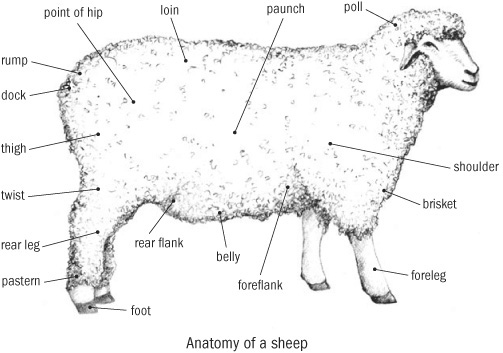

This sheep shows good conformation, with a nice straight back, a strong chest, legs well placed under the body, and so on.

This sheep is far less desirable, with a swayback and belly, hock-kneed legs, and a weak chest and neck.

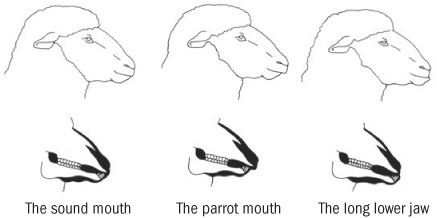

First, study the teeth and the shape of the head. Not only should the teeth be in good shape, but the bite itself is also important. As Paula’s friend Darrell Salsbury, DVM, says, “They can’t shear grass if the blades don’t match.” In a well-conformed animal, the upper jaw is the same length as, or just a hair longer than, the lower jaw. In other words, the teeth of the lower jaw have to line up with the dental pad of the top jaw.

TYPES OF MOUTH CONFORMATION

Next, look at the body. The back should be long and straight, and the belly should also be fairly straight. Both the chest and the pelvic area should be broad and firm. The legs should be widely set, fairly straight, and forward facing, with feet well placed on the ground. The rump should be rounded, with a slight downward curve, but should not look like a slope that you could ski jump off. Sheep being raised for meat should be large, with strong muscles and trim features. Sheep being raised for wool should have a slightly more angular body with dense, clean bright fleece.

In a mature ewe, look at the udder next. A healthy udder is soft and pliable, warm (but not hot) to the touch, and symmetrical with two good teats widely spaced on each side. The teats should not show signs of chapping or hardness.

The final thing to think about when planning your purchase is the general health of the animal. Determining a sheep’s general health should involve a close physical examination. If you’re considering purchasing a large flock from one seller, you may decide to closely inspect only a portion of the animals, but if you’re buying a small number of animals from one seller (say, fewer than 20), then take the time to give them all a complete examination. (See chapters 7 and 8 for an in-depth discussion of health.)

The animal should have no suspect discharges from the eyes, ears, or nose. Just as in people, if the weather has been cold and windy, a little clear fluid may discharge from the eyes or nose and not indicate anything of consequence, but if the discharge is crusty or full of pus or if there is excessive slobbering or frothiness around the mouth, beware. And there should never be a runny discharge from the ears, period.

Respiration should be easy and steady. Unless the animals had to be chased for their examination, they shouldn’t be panting or breathing heavily. If they were chased, let them rest for a few minutes. Their respiration should return to normal within about 20 minutes. Coughing and wheezing should be considered a warning of a real problem.

The wool or hair should be shiny and even. Clumpy fleece and bald spots may be a sign of poor nutrition, illness, or, most often, external parasites. Separate the fleece around the neck with your hands and look for signs of sheep ticks, or keds. (These are not a true tick, like what the dog picks up in the woods, but a wingless fly that passes its whole life cycle on the body of the sheep.) There may be a little mud around the ankles if the weather’s been wet, but there shouldn’t be caked manure in the wool. Manure around the rump and on the backs of the rear legs indicates scours (diarrhea) and is a definite problem.

Pick up the feet and look for signs of foot rot. The hooves shouldn’t be too overgrown. If any of the hooves look long, ask the owner to trim one while you watch. This is an easy way to learn how it’s done and how the feet should look after they’re properly trimmed. The legs should move fluidly with no signs of lameness or stiffness.

Closely inspect the whole body for rashes or for wounds that haven’t healed. Turn up the animal into the sitting position used for shearing (see chapter 11) to inspect the belly and the scrotum or udder areas. Several diseases manifest with skin lesions, and sheep with these disorders are best avoided. If there are wounds, are there signs of infection, like a hot red area around the wound or draining pus? During fly season, make sure there is no sign of flystrike, which is eggs in the wool or maggots or screwworms at the wound site. (Flystrike can also happen in the hooves of sheep with foot rot.) Minor wounds that appear to be healing correctly shouldn’t rule out an animal.

After you’ve inspected the animals, inspect the health records. Check the vaccination record. If you’re buying a ram, the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) should be negative for epididymitis. Some shepherds have had their flocks monitored for certain diseases, like scrapie, ovine progressive pneumonia, and Johne’s disease. If the flock owner has not done this type of testing, ask your local veterinarian which tests are recommended. The decision should be based in part on where you live, how many animals you’re purchasing, and whether the seller is willing to provide you with a healthy-animal warranty. (Also, while you’re talking to the vet, find out if there are any recommended changes to the vaccination program for the flock.)

So … congratulations — you’re the proud owner of some sheep. Now what? Before you even bring the flock home, make sure your facilities are ready (see chapter 3). A small holding pen or drylot that is well fenced should be the flock’s first stop.

Feed the same type of feed as the farm where your sheep came from. Before leaving the farm, ask the owner what kinds of forage or grain the sheep have been eating. If the flock was fed something that isn’t readily available at any feed store, buy some from the farmer. Then gradually change the sheep from their accustomed diet to whatever you intend to feed. Never change abruptly! (See chapter 6 for specifics on feeds and feeding.) To avoid scours and bloat, sheep should be given their fill of dry hay before being turned out onto a pasture that’s more lush than what they’ve had before.

As you unload the sheep, you can get a head start on preventing future health problems. If they need to be vaccinated, now is a good time to do it. And absolutely deworm them. Hold them in a drylot or small pen for 24 hours after you’ve given worming medicine; after they’ve passed any viable eggs, move them to a clean lot or pasture. Treat again 14 to 21 days later to kill any worms that hatched from eggs left after the first worming. This is the only time I recommend worming without bothering to take a fecal sample.