Y-DNA testing can help you find ancestors when other kinds of genealogical research fails. Here, Ben is trying to learn about his paternal great-great-grandfather’s ancestors.

You have a brick wall in the mid-1800s that you’ve been trying to solve for years. (I know you do, because we all do!) These brick walls can be incredibly stubborn, and every possible source of evidence, including DNA evidence, should be considered. Today, many of these brick walls are falling due to the power of DNA.

In addition to breaking down brick walls (or at least allowing you to see over them), genetic genealogy can provide evidence for supporting or rejecting hypothesized relationships and can confirm established and well-researched lines. In this chapter, we will examine some of the ways that DNA testing can be used to provide this evidence.

Both mitochondrial-DNA (mtDNA) and Y-chromosomal (Y-DNA) testing can be powerful tools for breaking through brick walls. In chapter 5, we examined how Y-DNA can be used to analyze a paternal relationship between two or more males, and in chapter 11 we’ll see several ways that Y-DNA testing can be used to help adoptees with their search. Using these techniques, Y-DNA can shed light on many of the questions asked by genealogists. Similarly, mtDNA can be utilized with almost identical techniques to help analyze and solve complex genealogical questions.

To confirm or reject a hypothesized paternal relationship—or to verify an established and well-researched paternal line—you need to test at least two males. Only in rare circumstances can a genealogical question be answered by testing a single male. One such circumstance is when a particular ethnic ancestry is being examined. For example, a family might suspect that a great-great-great-grandfather was Native American on his paternal line. A Y-DNA test of a direct-line paternal descendant will provide evidence to support or reject this hypothesis based solely on the haplogroup. If the Y-DNA belongs to a Native American haplogroup, the hypothesis is supported. If the Y-DNA does not belong to a Native American haplogroup, the hypothesis must be updated and possibly rejected.

Another circumstance where testing only a single male might yield results is if the test-taker has a large surname project to which he can compare his results. For example, a Williams man who tries to confirm his Y-DNA line by comparing his results to the results of known paternal relatives in the Williams surname project might only have to test himself. However, if his results indicate that he is not actually related to any of the Williams test-takers in the surname project, he will undoubtedly end up testing other individuals or wait for another individual to test and provide a closer match.

Similarly, for mtDNA, you’ll need to test at least two people—male or female—to confirm or reject a hypothesized maternal relationship or to verify an established and well-researched maternal line. In rare circumstances similar to those we saw with Y-DNA, including distinct ethnicities and DNA projects that incorporate mtDNA test results, mtDNA from a single person might provide sufficient information.

If Y-DNA is being utilized, the test-taker should consider a 37-marker test (or, preferably, a 67-marker test). For mtDNA, you should use a whole-genome test. In almost every case, it will be important to provide as detailed a relationship prediction as possible, and this cannot be done with low-resolution tests.

In the following example (image A), Ben Albro has hit a brick wall at his great-great-grandfather, Seth Albro. Ben has no information or clues about Seth Albro’s parentage or place of origin, and he hopes that a Y-DNA test might shed some light on the mystery. Ben has ordered a 37-marker test for himself, and when he receives the results he has several close Y-DNA matches:

Y-DNA testing can help you find ancestors when other kinds of genealogical research fails. Here, Ben is trying to learn about his paternal great-great-grandfather’s ancestors.

Ben is an exact match with both George and Victor Albro, who can trace their ancestry back to an Augustus Albro, born in 1790 in Rhode Island. Ben joined the Albro surname project before ordering his test, and shortly after his test results were available, the administrators let him know that he most closely matches the Job Albro haplotype, a group of individuals who are descended from Job Albro of Rhode Island. Ben now has significant clues as to where to look for Seth’s parentage, although it may not be enough to definitively identify Seth’s ancestry or even his paternal line. Autosomal-DNA (atDNA) testing may provide other clues for Ben to pursue, as discussed later in this chapter.

It is important to remember as well that a brick wall is not a prerequisite for Y-DNA or mtDNA testing. Even if Seth Albro’s ancestry had been well known, Y-DNA testing one or more of Ben’s paternal cousins can confirm the last few generations in each of his lines. Or test results might identify an unknown break in one of these lines that could then be analyzed. For example, Seth could have asked Aiden to take a Y-DNA test for comparison. If he (Ben) and Aiden were a sufficient match, Ben could confirm that both lines go back to the paternal common ancestor Seth Albro. Cousin Jim could not, of course, provide a Y-DNA sample since he is not a direct-line male descendant of Seth Albro.

Similar to Y-DNA testing, mtDNA testing can be used for examining complex genealogical questions. One important caveat, however, is that mtDNA is not as good as Y-DNA at estimating the genealogical distance between mtDNA matches. A perfect mtDNA match, even using whole-genome matching, can mean that two people share a very recent maternal ancestor or that they share a very distant maternal ancestor. Another caveat is that there will not be a correlation between the mtDNA and the surname of either the test-taker, the genetic match, or the ancestor in question. With mtDNA—unlike with Y-DNA—the surname will most likely change at every generation.

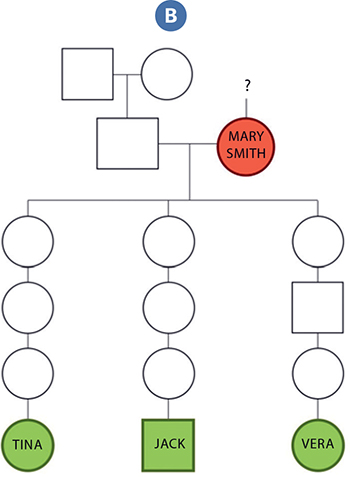

In this example (image B), Tina has hit a brick wall at her great-great-grandmother, Mary Smith. Tina currently has no clues or other information about Mary’s maiden name, her parents, or where or when she was born. Tina takes an mtDNA test with hopes that the results will shed some light on the mystery. When they come back, the results indicate that Tina has one exact mtDNA match: Ms. S. Connor, with a most distant ancestor of Jane Thompson (born about 1770 in Virginia) and the haplogroup A2w.

Like Y-DNA, mtDNA can be used to investigate genealogical questions. Tina can use mtDNA testing to find information about her maternal great-great-grandmother, Mary Smith.

Tina can now contact Ms. S. Connor to introduce herself and ask about this line. Although it is not clear if Tina and Connor are closely related within a genealogically relevant time frame, it is potentially an important clue that Tina should pursue.

If Tina is interested in confirming her line of descent from Mary Smith, she could also ask her cousin Jack to take an mtDNA test. Although Jack is a male, he should have the same mtDNA as Tina if Tina’s research is correct. If they do indeed share the same mtDNA, that would confirm both lines of descent back to Mary Smith. Cousin Vera, in contrast, is not a suitable relative to take the mtDNA test because Vera’s grandfather created a break in the mtDNA line between Vera and Mary Smith.

These are just a few examples of how mtDNA and Y-DNA can be used to examine and possibly answer complex genealogical questions. To stay on top of the latest developments and learn about other ways to utilize mtDNA and Y-DNA, join surname projects, haplogroup projects, and/or geographic projects at resources like Family Tree DNA <www.familytreedna.com> to interact with other genealogists in forums and social media and read about success stories in works of genealogical scholarship.

atDNA is perhaps the most promising new tool for analyzing complex genealogical questions. As the sizes of the atDNA databases grow, and as family tree data is combined with the results of atDNA testing, the power of DNA will continue to grow. Many questions that previously could not be analyzed—much less answered—might be easily addressed by atDNA. In this section, we will look at several different ways that atDNA can be used to examine genealogical questions, including both segment and tree triangulation, among other methods.

One of the key considerations in any DNA testing plan is deciding who should be tested. In a perfect world where money grows on trees, we could test every possible relative who agreed to testing. In the real world, however, we have finite resources and must be more careful about testing. Accordingly, when examining a specific genealogical question, we must first test the individual or individuals who are most likely to provide evidence about that question.

In the example displayed in image C, Mike would like to identify the parents of his ancestor, David France. Mike has taken an atDNA test at each of the three testing companies and transferred his DNA to GEDmatch <www.gedmatch.com>, but he has not yet uncovered any strong evidence of David France’s ancestry. Mike currently has funds for one atDNA test, and he would like to know which person to ask to take the test for him. He has four potential candidates: Mona (his aunt), Sue (his great-aunt), Matt (his second cousin), and Joy (his second cousin once removed).

Mike can use atDNA to find David France’s parents. He has many potential test-takers (such as Mona, Sue, Matt, and Joy) to choose from.

So who should Mike pick? Any of these relatives will potentially provide relevant information and genetic matches, but Sue and Joy are likely to be the best candidates for atDNA testing given the set of facts. Sue and Mike will only share DNA from one additional set of ancestors (indicated in blue in the image). In contrast, Mike and his aunt Mona will share many more ancestral lines in common, and it will be difficult to narrow any shared DNA or matches to just those that result from David France and his unknown parents.

Joy is a good candidate because any DNA that Mike shared in common with Joy likely came from David France and his wife (barring any other recent ancestry on their other ancestral lines). This significantly increases the importance of any shared DNA/matches by Joy and Mike, all of which could potentially be of interest and should be pursued. However, Mike will likely share less DNA with Joy than he will with Sue, although the DNA shared with Joy will potentially be of greater interest. This is a circumstance where, like so many others involving atDNA, there is no definitive answer until the tests are ordered and analyzed.

To maximize the information obtained by atDNA testing, you’ll often have to test multiple descendants of an ancestor or ancestral couple. For example, if Mike eventually expands his research and identifies more descendants for testing, he will greatly increase his chance of finding genetic matches with good family trees that are related to him through David France. Mike can test Mona, Sue, and Joy (or the ancestors in blue) to obtain additional information and test results.

Not only will Mike identify segments of DNA that he shares with each of these individuals, but he will also identify segments of DNA shared by other descendants and not shared with Mike, thereby forming a genetic network of segments and shared matches that can be mined and explored. Even segments that are shared by just two of the descendants can be utilized in this genetic network research project.

Tree triangulation is a term coined by the genetic genealogy community to refer to finding shared ancestors among the trees of close relatives and building a potential family tree connection using those shared ancestors. At its most basic form, tree triangulation typically involves the following steps:

Step one of the process will typically involve reviewing many family trees of close relatives to find patterns of surnames and ancestors. For example, if you observe that the Philips surname is found in several of the family trees, additional research will be needed to determine whether it is the same Philips surname, which will be further supported if the genetic matches to whom those family trees belong are shared in common with the test-taker, at step two of the method.

As an example, Dianna reviews the family trees of her closest matches at AncestryDNA, including a predicted second cousin and ten predicted third cousins. The second cousin has a family tree, as do five of the third cousins. While reviewing these family trees, Dianna notices that the Pierce surname is found in both her second cousin’s family tree and one of her third cousins’ trees. The trees suggest that her second cousin and third cousin are themselves second cousins, and the Shared Matches tool at AncestryDNA shows that they do in fact share DNA in common. The tool also shows that they both share DNA with another third cousin that has a Worthington line that is collateral to the Pierce line in the family trees of the second and third cousins (i.e., the Worthington line married into the Pierce family). This is an incredibly strong clue that Dianna is either very closely related to or descended from this same Pierce family, although other lines will have to be considered until additional information or matches are available. Dianna can now pursue this lead and fill out the family tree of this Pierce family.

Tree triangulation is still a relatively new and unexplored methodology, and thus has not yet reached its full potential. It is expected that this methodology will continue to gain new adherents and mature as more people explore and understand the concepts underlying the process.

One of the primary goals of atDNA research is to find a common ancestor with a genetic match, which allows you to assign the segment of DNA shared with that genetic match to the common ancestor. This process of identifying the potential source of a segment of DNA is called segment triangulation. Triangulation is extremely challenging and comes with many caveats, but can potentially facilitate the identification of common ancestors shared with new genetic matches.

More formally, triangulation can be defined as a technique used to identify the ancestor or ancestral couple potentially responsible for the DNA segment or segments shared by three or more descendants of that ancestor or ancestral couple. Triangulation involves the combination of DNA and traditional records in order to assign a segment of DNA to an ancestor. In chapters 6 and 8, we learned about the different chromosome browsers available from the testing companies and GEDmatch. These chromosome browsers are important sources of the information needed for triangulation.

Triangulation is a very advanced technique, and is one of the most time-consuming methodologies currently used by genetic genealogists. Accordingly, it should only be considered if the lower-hanging fruit of tree triangulation and similar methodologies have not provided the necessary information. Triangulation works by either using a third-party tool that automates the process, or by creating a spreadsheet with segment data including at least the chromosome number, start position, and stop position of each shared segment. Once the third-party tool is utilized or the spreadsheet is created, the test-taker can look for segments of DNA that are shared in common by two or more other individuals. If there are at least three people who share a segment of DNA and share a common ancestor, that is evidence—but not proof—that the segment of DNA may have come from the common ancestor.

Download segment data from each of the testing companies and/or from GEDmatch. For example, 23andMe <www.23andme.com> and Family Tree DNA both provide segment data for download into a spreadsheet. Family Tree DNA provides the information for all genetic matches, while 23andMe only provides the information for individuals who share genomes with the test-taker. In contrast, AncestryDNA does not share any segment data with test-takers. As a result, the only way to get segment data from matches at AncestryDNA is to ask them to upload their raw data to GEDmatch where segment data is freely available.

You can obtain your segment data from GEDmatch fairly easily by following a few steps. First, perform a One-to-many DNA comparison using the kit of interest (see chapter 8 for more details). Click the Select box for any individuals of interest in the One-to-many DNA comparison result list, then click Submit on the same page. On the next page, click Segment CSV file to obtain a spreadsheet of segments shared with the individuals of interest.

Upload your segment data to GEDmatch, then perform a One-to-many DNA comparison and download a CSV file of the segments.

Once the segment data is obtained from 23andMe, Family Tree DNA, and/or GEDmatch, it can be collated into a single master spreadsheet. You can use various column titles, such as:

Most likely, the spreadsheet is many thousands of rows long, and most of this data is small segment data. Many genetic genealogists then remove some or all of the small segments from the spreadsheet, and you’ll need to find some way of sifting through all that data. For example, I always sort the spreadsheet in Excel or the spreadsheet program by the cMs column (from larger to smaller), then delete any row where the shared segment is less than 5 cMs. Don’t fret if this is a significant percentage of the spreadsheet. These small segments can be problematic, and at least one study has suggested that the majority of segments of 5 cMs and smaller are in fact false positives. Once you master this process, you can go back and use the smaller segments with caution.

Once the small segments are removed, sort the spreadsheet by chromosome and start location. This will align the segments into potential triangulation groups, or groups of potentially overlapping shared segments of DNA.

GEDmatch allows you to download your segment data in spreadsheet format, allowing you to sort by a number of categories like chromosome number and length of shared segment.

GEDmatch and DNAGedcom <www.dnagedcom.com> have many tools to assist you with triangulation, and we examined some of these in chapter 8. For example, JWorks is an Excel-based tool that allows you to create sets of overlapping DNA and assign ICW status within the sets, and KWorks is similar to JWorks, except it runs in the browser. Note that the output of the two programs is based on ICW status and thus is not actual triangulation. Based solely on these analyses, you don’t known for certain if the individuals share the actual identified overlapping segments in common, just that they share some DNA in common.

GEDmatch also has some other tools to help with triangulation. For example, among the Tier 1 tools is the Triangulation tool, which identifies people in the GEDmatch database who match the test-taker, then compares those matches against each other to perform true triangulation. Results can be sorted by chromosome or kit number and can be displayed in either tabular or graphical form. The results can be fine-tuned by setting a minimum (to remove small segments) and/or maximum (to eliminate close relatives) amount of DNA to be displayed.

DNAGedcom also offers the Autosomal DNA Segment Analyzer (ADSA), which is a visual ICW and triangulation tool. ADSA constructs online tables that include match and segment information as well as a visual graph of overlapping segments, together with a color-coded ICW matrix that allows pseudo-triangulation of segments.

The goal now is to find triangulation groups, or groups of three or more people who not only share a similar segment of DNA, but are known to share that segment of DNA in common. If you don’t know whether they share the segment of DNA in common, they do not form a confirmed triangulation group. Instead, they would form a pseudo-triangulation group.

In order to find triangulation groups, you will need to learn whether members of a potential group share the segment in common. This can be accomplished using, for example, the following tools:

Let’s look at an example. Assume that I download my segment data from Family Tree DNA, 23andMe, and GEDmatch and use that information to create a master spreadsheet. Analysis of the spreadsheets reveals that I share a segment of DNA in common with four individuals on chromosome 3, between 20 and 40 cMs in length. Without more information, I do not know whether these matches share DNA with each other, and thus whether the five of us form a single triangulation group.

If the four individuals have also tested at Family Tree DNA, I can use the ICW tool or the Matrix tool to determine which of these four individuals share some DNA in common with each other, although I won’t know if they share the exact segment of interest in common. However, I might be able to use the information to create potential or pseudo-triangulation groups. When I use the Matrix tool, I see that the five individuals form two groupings: one group with three people who all share DNA in common and a second group with two people who share DNA in common. I, of course, am a member of both of these groups. Although I haven’t confirmed using the Matrix tool that these are the actual triangulation groups, based on the results I am fairly confident that the groupings are accurate. I will also try to confirm the groupings at GEDmatch if the individuals have transferred their results to the third-party tool.

Once I have the identified triangulation groups, we can now work together as groups to compare our family trees and potentially find an ancestor in common who might be the source of the shared DNA.

Compile your segment data from testing companies and GEDmatch to analyze what segments you share with other individuals. Once you have this information, you can run an ICW analysis to see what DNA you share in common.

Both tree triangulation and segment triangulation are good methods to create clues for further research and add evidence to an existing hypothesis. However, neither tree triangulation nor segment triangulation is error-proof. Both methods are susceptible to a major concern, one that must be adequately addressed in any conclusion or proof argument that relies on its findings: A segment of DNA could have been inherited by another ancestor, possibly one not known to be shared by all the matching cousins.

For example, in the table in image D, a genealogist has determined the number of possible ancestors in each of the past ten generations, as well as that individual’s known ancestors for that generation (where “known” means having some information about the ancestor). The table suggests that while there is decent information about the genealogist’s ancestry through the sixth generation or so, the genealogist is missing information about at least 36 percent of her family tree at the seventh generation. This poses a serious limitation on any effort to identify a shared ancestor in this generation or beyond.

While triangulating ancestors using DNA can be effective, you likely won’t be able to discover all of your direct-line ancestors through triangulation. In the example above, for example, the test-taker is able to find fewer and fewer of his genealogical ancestors as he goes farther back in time.

In any event, genetic genealogists should recognize the possibility that DNA could be shared through other lines, and consider that possibility when reaching their conclusions.

In addition to encountering significant gaps in the family trees of members of a triangulation group, you may also face the possibility that a shared segment of DNA—particularly smaller segments—may be so common within a population that trying to narrow its source to one ancestor is problematic. For example, if segment X is common within a particular population, and a genealogist is descended from several different members of the population, knowing from which one of those ancestors the segment was inherited is extremely challenging.

For more information about the benefits and limitations of triangulation, including links for additional reading, see the Triangulation page at the ISOGG wiki <www.isogg.org/wiki/Triangulation>

These are just a few examples of how DNA can be utilized to examine and possible answer complex genealogical questions. This is one of the most actively studied areas of genetic genealogy, and it is likely that new methodologies, company tools, and third-party tools will find new ways to maximize the results of DNA testing.

Y-DNA and mtDNA are both very useful for examining complex genealogical questions, as long as the limitations of those DNA tests are carefully considered. Likewise, atDNA is a powerful new tool for genetic genealogists analyzing genealogical questions and mysteries.

In tree triangulation, researchers find shared ancestors among the trees of close relatives and build a potential family tree connection using those shared ancestors.

In segment triangulation, researchers identify the ancestor or ancestral couple potentially responsible for the DNA segment or segments shared by three or more descendants.