The word ‘liberal’, with its connotations of freedom and generosity, has been used to describe a range of very different political ideologies. Used loosely, it has come to mean something similar to ‘left-wing’, especially in the USA, where it has even taken on a pejorative connotation. However in political theory, liberalism has a more precise meaning, referring to a philosophy based on principles of liberty and equality.

From its beginnings in the political philosophy of the Enlightenment period, liberalism has advocated ideas of democracy and civil rights, particularly for the individual, and developed into a movement supporting social reform. At the same time, a strand of economic liberalism has advocated free trade and minimal government interference. It is perhaps better then, rather than defining liberalism in terms of left or right, to see it as a broad range of social and economic stances that together sit at one end of a scale, the other end of which is occupied by authoritarianism.

During the Renaissance, science and humanist philosophy began to challenge the authority of religion and hereditary privilege. This notion continued into the Enlightenment, when rational thought continued to replace faith and adherence to convention. The first politically liberal thinkers focused their attention on individuals as citizens of their societies, rather than their governments and leaders. And these individuals, especially in the fledgling democracies being established at the time, were citizens, not subjects.

Liberalism grew from the premise that individuals should have the opportunity to live their lives as they wish, and that government should enable them to do so, with minimal interference with their individual liberties. The supremacy of individual rights over state authority became the fundamental principle of classical liberalism, summed up in the dictum of the British 19th-century liberal philosopher John Stuart Mill: ‘over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign’.

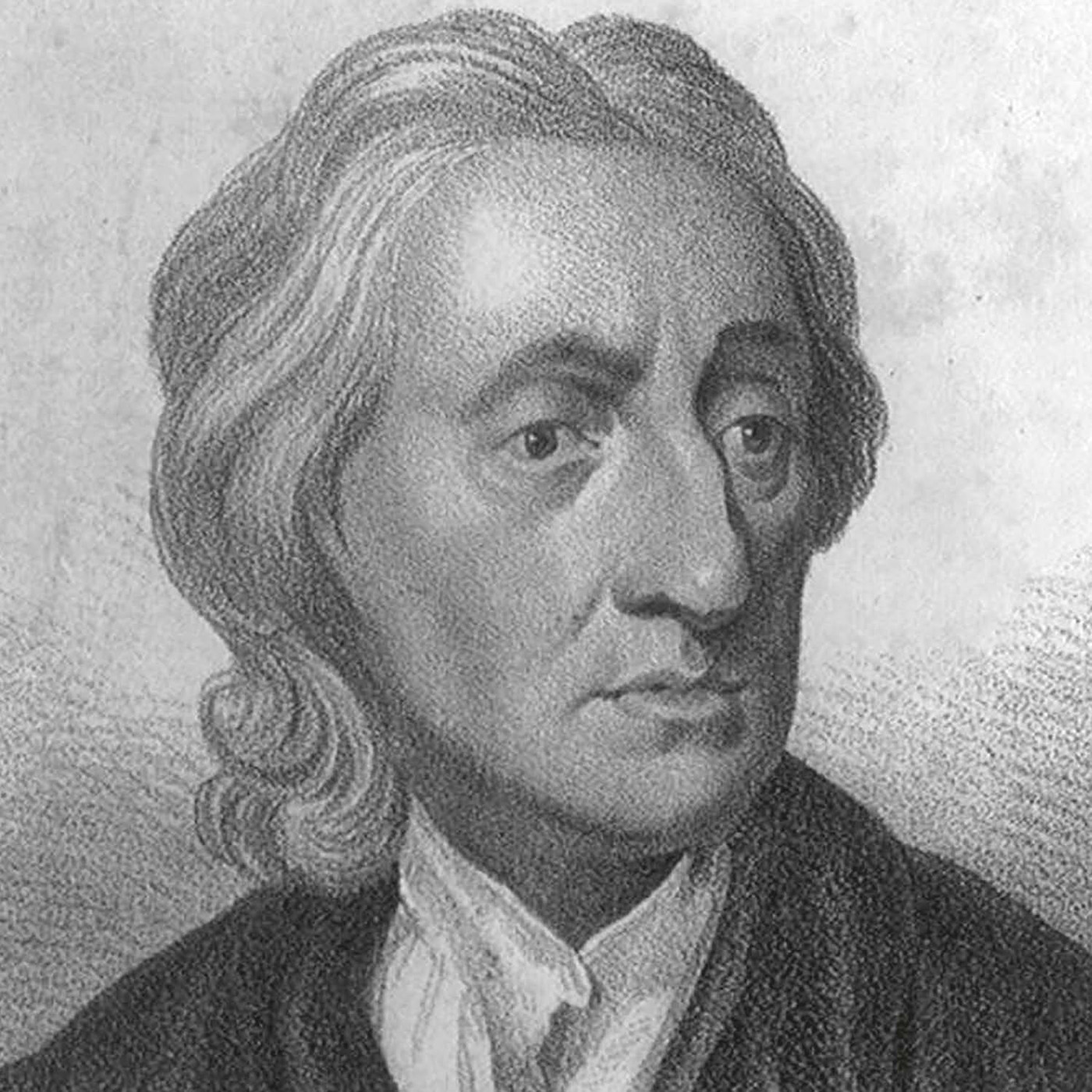

An important element of liberalism is the emphasis on the rights of individuals to go about their lives freely. Traditionally, it had been thought that rights are divinely granted, and these were cited in defence of institutions, such as hereditary privilege and the power of the clergy, but during the Enlightenment philosophers such as John Locke (pictured) argued that there are some natural rights that are applicable to every human being. These, he said, are not only universal, but inalienable: they are not granted by a leader, government or religion, and do not depend on the beliefs and culture of a society, nor can they be restricted or removed by them.

These universal and inalienable natural rights to life, liberty and property are the foundations of the liberal ideology, and have been enshrined in the constitution of republics, such as the USA and France. They are, however, only the most basic of rights, which can be supplemented by legal rights granted to individuals by governments and legal systems.

One of the natural rights recognized by the US constitution, the right to ‘pursuit of happiness’, sounds a little curious to modern ears. But it reflects the concern of classical Greek philosophers with the pursuit of ‘the good life’, and moreover a contemporary notion that morality can be judged by the amount of happiness or harm caused by an action: its ‘utility’. Utilitarianism was pioneered by the British philosopher Jeremy Bentham, who believed happiness is measurable, using a ‘calculus of felicity’. The best course of action can be determined by the one that gives the greatest happiness to the greatest number of people. The concept of ‘the greatest good’ was further developed by John Stuart Mill, who more than Bentham saw its implications in terms of governments enabling citizens to pursue happiness. Mill also developed the idea of measuring happiness against harm, advocating laws that allow not only the greatest happiness of the greatest number, but also that cause least unhappiness, either by actual harm or restriction of liberty.

Surrounded by the revolutionary atmosphere of the late 18th century, liberalism as a political movement flourished – perhaps surprisingly – in Britain. As well as the social liberalism built on Locke’s championing of natural rights and Bentham’s utilitarian moral philosophy, the Scottish political economist Adam Smith laid the foundations of liberal economic theory, based on the principles of the free market.

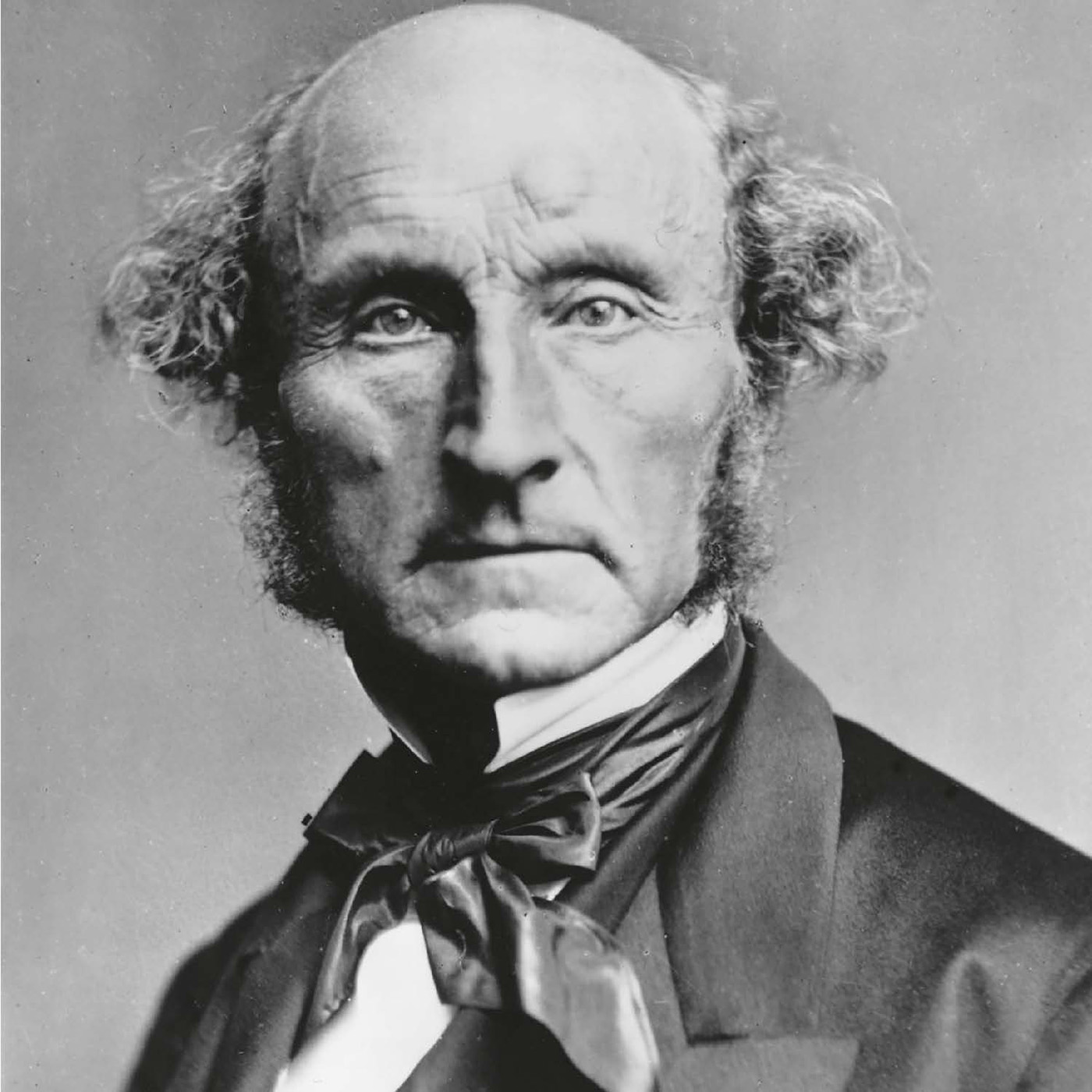

The most prominent British liberal thinker was undoubtedly J.S. Mill (pictured), whose 1859 book On Liberty set out the principles of liberalism in terms of ‘the nature and limits of the power which can be legitimately exercised by society over the individual’. This introduced the concept of social liberty – freedom from the tyranny of political rulers, but also from the tyranny of the majority. Mill advocated that this could be achieved by establishing a number of civil and political rights, and a democratically elected government whose power is restricted by the requirement to recognize these rights.

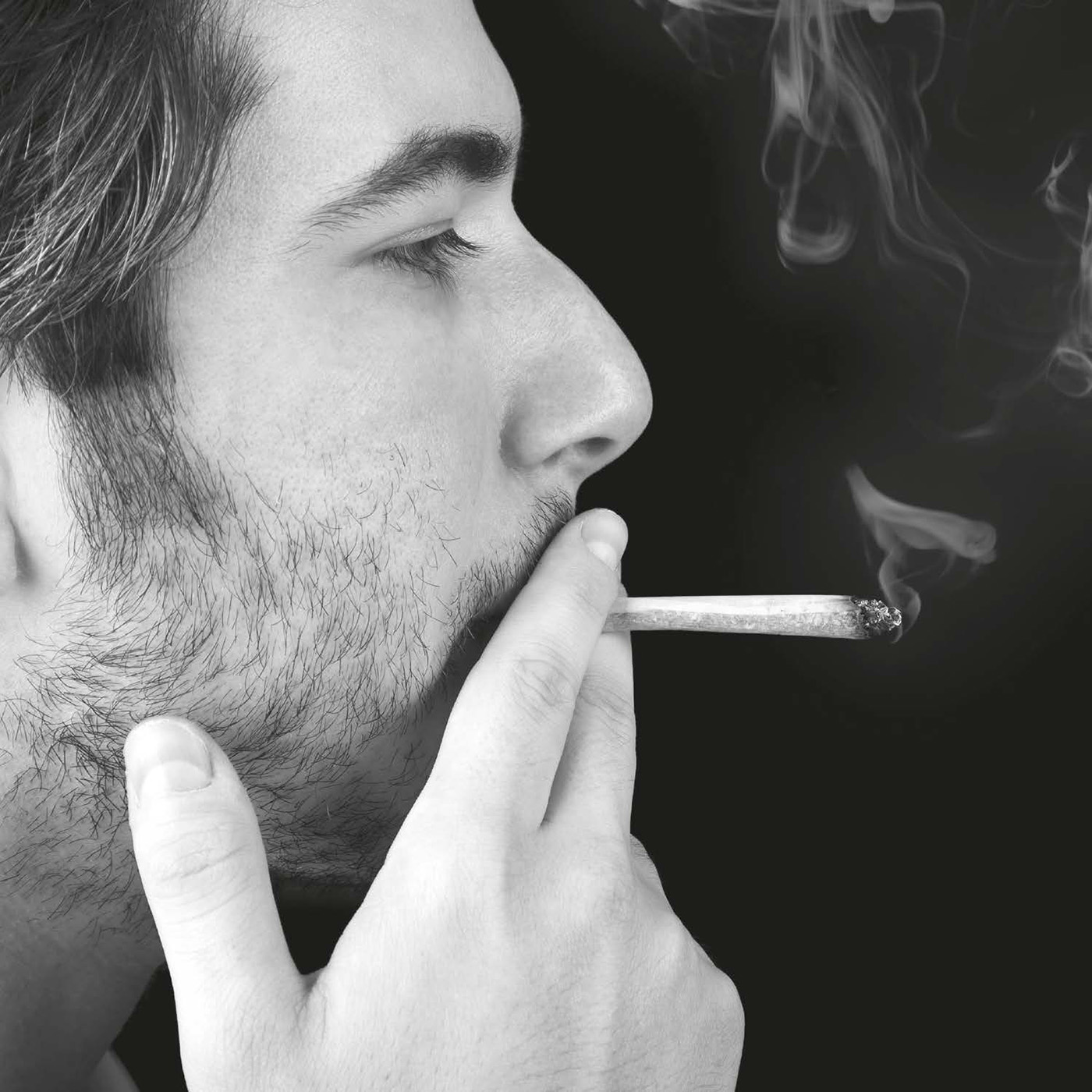

The fundamental principle of Mill’s concept of liberalism was that every individual should have the liberty to live life as he or she pleases, without interference from others. But this principle raises a number of ethical questions, in particular in relation to the fact that allowing someone to do something may hurt other people, or restrict their freedom to do as they please. Mill suggested therefore that the individual’s liberty should have its limitations when it harms others, and that it is the duty of society to prevent that harm.

He also recognized that some acts of omission – failing to do something that results in someone else’s suffering – have the same effect. According to this ‘harm principle’, there is justification for some government regulation of the freedom to pursue happiness. But, as Mill pointed out, only to prevent harm to others – provided he or she is not being forced or tricked into doing something, the individual should be permitted to make decisions about his or her own well-being.

Another cornerstone of liberalism is the concept of tolerance, that if someone is not actually harming anyone or interfering with their pursuit of happiness, they have the right to do as they please. Linked to this are specific liberties such as freedom of speech and of the press, and freedom of religion and political allegiance. The tolerant atmosphere in countries espousing these liberal principles, such as Britain and the USA in the 19th century, made them havens for refugees who were persecuted for their beliefs elsewhere. However, tolerance is now being tested in the multicultural societies that were created in part by such liberal acceptance, as some indigenous populations feel their way of life is threatened by immigration. Tolerance of freedom of speech and religion, too, is challenged by those who claim to be offended by opposing views. There is a difficult balance to be struck in our tolerance of religious or cultural customs that conflict with those of the wider society, such as arranged marriages or inhumane methods of animal slaughter.

Perhaps more than any other nation, the USA is founded on the principles of liberalism, with its commitment to equality and the inalienable rights to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness. But ‘liberalism’ has in the USA taken on a variety of meanings since that declaration of independence. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, American liberalism was associated with the values of individualism, independence and self-responsibility that had become ‘the American Way’, with a dislike of too much government interference, especially in economic matters. Classical liberalism’s emphasis on self-reliance meant an opposition to government spending on welfare, but the Great Depression of the 1930s forced liberals to soften their stance on social policy. F.D. Roosevelt’s New Deal marked the beginning of a new kind of US liberalism, with increased government involvement in both social and economic matters. This strand of progressive liberalism continues to the present in the policies of the Democratic party, contrasted with the conservatism of the Republicans.

While in Europe liberalism was increasingly influenced by socialist ideas, especially in areas of welfare, public health and education, American liberalism stuck more to the classical principle of minimal government authority over the freedom of the individual. This American attitude was summed up by the writer Henry David Thoreau: ‘government is best which governs least’. Classical liberalism considered government as something of a necessary evil, and laws and regulation as obstacles to personal liberty and, above all, free enterprise.

The notion of small government persisted in the 20th century, in the form of an opposition to the rising tide of socialism. This interpretation of liberalism, with the emphasis on small government, deregulation of commerce and minimum public spending rather than individual liberty and equality, developed from the free-market capitalism espoused by 19th-century liberals. Now it is the orthodoxy not of the progressive liberals, but the socially and economically right-wing conservatives.

Liberalism as a political movement began with the ideas of John Locke, and was first put into practical form by the founding fathers of the US republic in their Declaration of Independence. They realized that liberty and rights were closely linked to limiting by law the powers of any government. A government would only be considered legitimate if it remained within the legal limitations, which they set out in a constitution.

Constitutionalism is the belief that a government’s authority derives from the constitution. This belief is, however, not as simple as it seems: the laws limiting government are themselves created by government. The implication is that the constitution represents a higher authority than that of the government, and the limitations on governmental power must be so entrenched that they are resistant to change or repeal, and enshrined in a written constitution. That is not to say that the ‘higher law’ of the constitution is fixed, but that changes to it cannot be made lightly.

The basic principles of liberalism – protection of individual rights of liberty and protection against oppressive government – have been so widely accepted that they are sometimes seen as synonymous with the idea of democracy. Although democracies may take on a variety of forms (see here), today most describe themselves as liberal democracies in that they combine the democratic principle of fair and free elections with the liberal principle of protection of rights and freedoms. However, in practice, democracies can and do limit certain freedoms, and many governments in so-called liberal democracies impose regulations on trade and industry, and the free movement of labour, and control the distribution of wealth through systems of taxation. In addition, they may take an active role in social policy. The justification for this type of intervention is typically that it is sometimes necessary to become less liberal in order to be more democratic; that restrictions and regulation may be needed to protect certain basic freedoms, and even democracy itself.

Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution, proposed in his 1859 book On the Origin of Species, gave rise to a number of theories of society in the late 19th century, linking the idea of ‘the survival of the fittest’ to liberal political ideology. This social Darwinism, as it became known, argued that the strongest and richest sections of society should be allowed to prosper without restriction by government regulation, and that protection of the weak and poor through welfare programmes and redistribution of wealth runs counter to the evolution of a healthy and prosperous society. This provided a rationale for small government and minimal social spending, and in particular for a laissez-faire approach to competitive capitalism. The idea of allowing unproductive sections of society to die out, enabling the strong to prosper, was rejected by mainstream liberals as aggressive individualism. However, some vestiges of the concept can be seen in classical liberal policies, such as the encouragement of successful enterprise to promote economic growth and opposition to a socialized welfare state.

English classical liberal political theorist Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) is today best known as the author of the expression ‘survival of the fittest’.

J.S. Mill, one of the greatest advocates of liberal ideology, initially advocated government only to protect those rights, and believed in an unregulated free-market economy without the burden of excessive taxation. But he later came to recognize that individual freedom is not incompatible with the good of the community and liberalism should also concern itself with social justice. Persuaded by what he saw as social injustices in Victorian Britain, he proposed that government economic policy should aim to mitigate poverty, and have a role in public health and education. This strand of British liberalism gained support, leading to radical social welfare programmes and unprecedented progressive taxation, introduced at the beginning of the 20th century by liberal governments. These paved the way for a comprehensive welfare state in the UK after the Second World War. And it was an English liberal economist, John Maynard Keynes, who provided President F.D. Roosevelt with the framework for his New Deal, bringing social liberalism to the USA in response to the Great Depression.

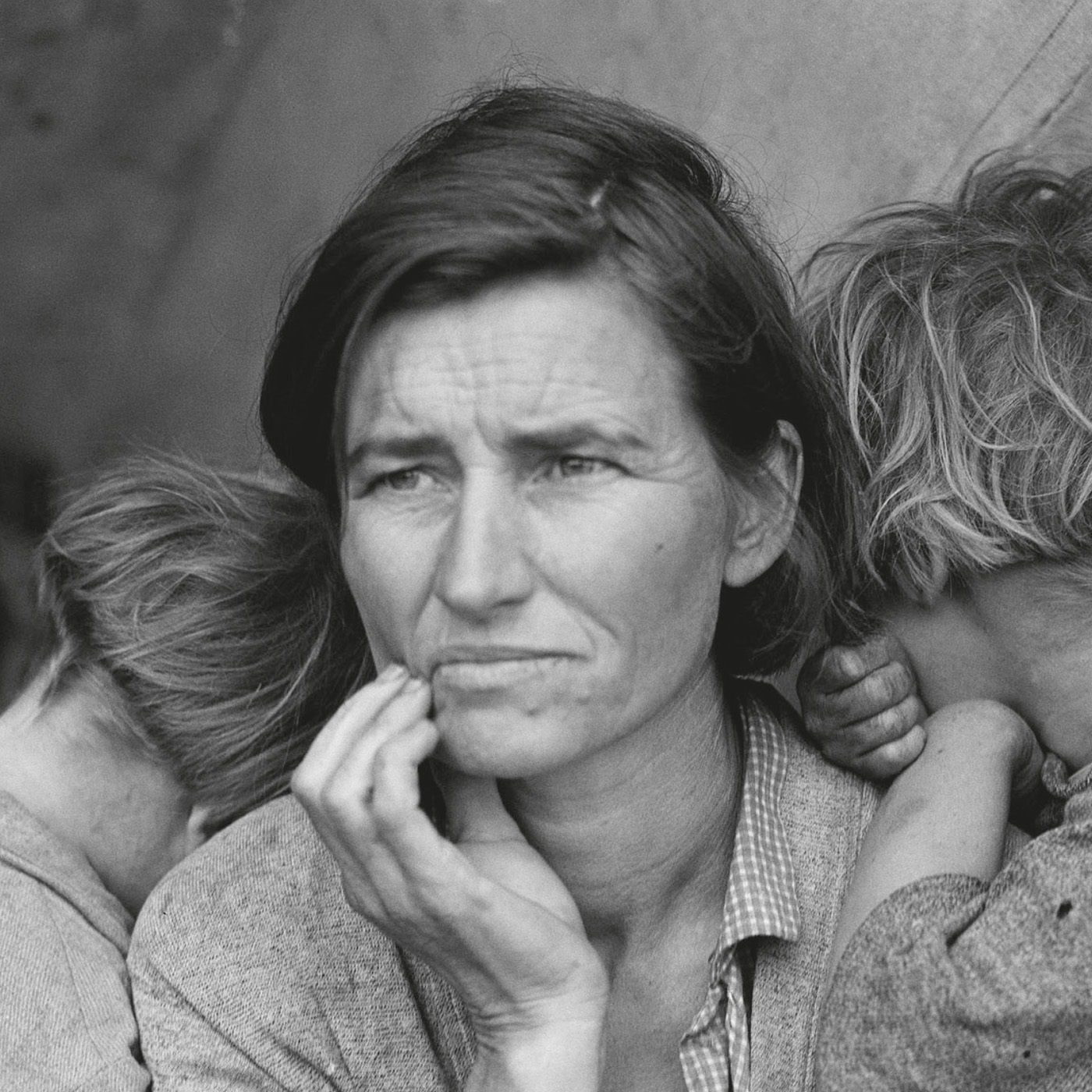

The crisis triggered by the Great Depression and Dust Bowl of the 1930s plunged many Americans into poverty – a crisis that was finally remedied with the introduction of the New Deal.

During the Enlightenment, a sea change in the approach to ‘political economy’ provided the basis for liberal economic thinking. In 1776, Adam Smith published The Wealth of Nations, which laid the foundations for modern economics, and provided the rationale for an economic model that has been at the heart of liberal democracies ever since. Smith argued that people are rational and act in their own interests if left to their own devices. In commerce, their actions are influenced by the laws of supply and demand; order and equilibrium is maintained by the ‘invisible hand’ of a free and open market.

Smith asserted that if business is left to operate in a free market, individuals and firms work to their mutual benefit and ultimately for the good of all. The idea that a market economy, free of restriction by government, would bring stability and prosperity to the community as a whole fitted ideally with liberal philosophy, and has figured in all forms of liberal economic policy.

Economic liberalism, the belief in a capitalist market economy and private ownership of the means of production, is contrasted with social liberalism (see here), and the two are sometimes awkward to reconcile. But while classical liberalism, and later neoliberalism (see here), have strictly applied the principles of free-market economics, there has always been a strand of liberalism that concedes there is a place for some government intervention and regulation of commerce, and that certain public goods and services are legitimately the responsibility of the state.

A commitment to free trade and open competition, for example, does not preclude regulation to prevent monopolies, or tariffs to control competition from other countries. Even in the most liberalized economies, trade is never entirely free – copyright and patent laws, immigration control and taxes all place some restrictions on the markets, and government subsidies and even bailouts give some firms a competitive advantage.

By the mid-20th century, liberalism had evolved from its classical roots of minimal government power over the rights of the individual and minimal intervention in economic affairs, to the social liberalism of a market economy guided and regulated by the state protecting the welfare as well as the rights of its citizens. But a number of economists, notably Friedrich Hayek and Milton Friedman, advocated a much more laissez-faire attitude to economic policy, termed ‘neoliberalism’.

These ideas were aggressively enforced by the dictator Augusto Pinochet in Chile during the 1970s, but gained respectability when this economic liberalization was adopted in the USA and Britain by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher. In essence, it was a reversal of the trend towards social liberalism, and instead a strengthening of the free markets, through a programme of reduction in government spending, especially social spending, lowering of taxation, deregulation of business and banking, and extensive privatization.

A central concept of liberalism in all its forms has been the limitation of government’s powers to what is necessary and good for society as a whole. Classical liberals argued that government should be confined to defence, administration of justice and public works. As social liberalism replaced classical liberalism, the understanding of what constitutes ‘public works’ expanded – in addition to defence and justice, liberal governments considered social issues to be the responsibility of the public sector, and even utilities such as water, gas and electricity, and public transport. In the 1980s, however, neoliberal economists argued that public ownership led to inefficiency, and many Western governments began the process of returning these businesses to the private sector. Since then, many European countries have not only reversed the public ownership of utilities, but also privatized traditionally national industries and services, such as post offices, and outsourced the work of government departments, such as prison services, tax collection and policing, to private firms.

In Europe, many railways started out as private enterprises, were later nationalized, and have more recently been privatized once again.