CHAPTER EIGHT

Understanding a New World

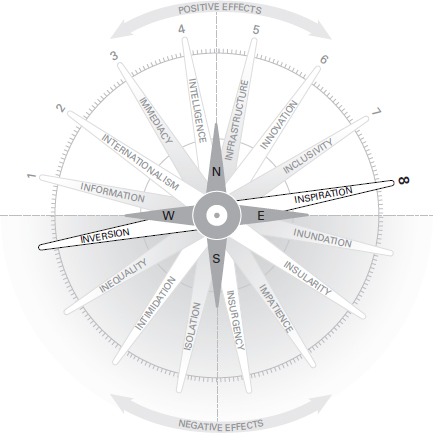

By this stage of the book, it’s clear that every one of the Kythera spokes, be it economic, behavioural, geopolitical or gender, describes a significantly changed (and changing) environment. The promise of the future is exciting and inspirational. If we get it right, we’re looking at an infinitely more sustainable, fairer, productive, efficient world, with greater access to education and information. A world that is healthier, better led, more optimistic and inclusive. The opportunity is compelling. The problem is that we need to tackle an inverted world to get there. For instance, despite all the indications that we’re living longer, with less violence,1 with greater wealth and better opportunities, cynicism and the opposite perception abound. Much depends on our viewpoint. If we choose to see positivity, then the Kythera tilts in our favour. If not, we remain fixated on the visible differences and iniquities that remain. Both views can be true simultaneously. It is up to us to choose.

In an atomized, rational, tangible, left-brained process world, the thing that could grant us greater happiness is what the left-brain process abhors. This is the intuitive sense of belonging, honesty, compassion, faith and trust. These are the values that unite us and that we believe in. While we can’t measure them or prove them, none of us wants to live in a world without them. The left-brain process discerns the difference. The right-brain process feels the unity. The overload and the interruptions all push us more towards the left-brain process, and this has profound implications. It makes us much more attuned to spot differences and logical non-sequiturs. The balance of our lives has shifted away from unity.

Let’s take the behavioural climate, for instance. There once was wide agreement about shared values. It involved patience, self-sacrifice, deferred gratification, commitment, modesty, frugality, public service, group identities, improving the condition of the poor, family integrity, marriage, children and church attendance. In the past 25 years, we’ve seen a massive erosion of this consensus. This is what we will investigate in this chapter.

The world is not only stranger than today’s leaders believe. It is stranger than many leaders are capable of believing. This is not just a case of recognizing intergenerational value change, but of identifying enduring values around which leadership can be founded. In modern times, these notions are more complex. The challenge is to find the unifying factors in the modern team.

QUICK TIP This is not just a case of leadership becoming aware that one or two vectors have changed. It needs to recognize that the majority of the vectors have changed.

Why does this matter for leaders? To unify, leaders must identify and develop common values to understand what is now perceived as ‘good’ or moral behaviour.

This is what we will cover:

- Through the looking glass

- Can we trust our leaders?

- A truly mixed reality

- Should we still work hard and save?

- Should we be patient and work together to get results?

- Is education worth it?

- Looking for a new domestic politics

- Now our friends spy on us, too

- Inversion and alignment

- Is success always rewarded?

- Is it only the bad guys who use torture?

- Does morality matter?

- Whatever happened to the future?

- A new multipolar world with walls

- Globalism is over

- Conclusions

Through the looking glass

Just about every one of our values, truths and standards has undergone a complete transformation. Our grandparents might well marvel at the technological developments of today, but they would be horrified in other ways. We have alleviated poverty, disease, famine and large-scale warfare. We have substantially reduced heart disease and cancer yet created an information culture that would bewilder them. We have also, however, presided over more debt, greater income inequality, environmental damage and more consumption than ever before. Despite more material wealth, we have rising inequality, isolation, ignorance, impatience, anger and unhappiness.

Our forebears struggled against so many of the challenges we have successfully met. For instance, food is now in such abundance that obesity, rather than starvation, is the most significant threat to Western health. To them, the rich were fat and the poor were thin. Today, that is inverted.

Our sources of truth have changed, too. We have a multiplicity of sources, but don’t trust any of them. Where previously there were one or two sources that sounded like the BBC or Walter Cronkite, today that, too, has become inverted. We live with fake news and alternative facts. The news is not news. It is profitable entertainment.

In court, you still have a choice of whether to use an oath or an affirmation. The oath is: ‘I swear that the evidence that I shall give, shall be the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth, so help me God.’ The affirmation is: ‘I solemnly affirm that the evidence that I shall give, shall be the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.’ The law has no truck with what is or isn’t a fact. There are no semantics in the oath. Yet despite the oath, of all the exclusions in the Ten Commandments, Thou Shalt Not Lie is a glaring one.

The availability of facts seems somehow inversely correlated with their use. Either that, or people are choosing to wilfully ignore them because facts are a bit dull. The abundance of facts seems to devalue them. The notion that you can prove anything with statistics has taken hold. Now, what you believe is more important than what you can prove. This prompts questions. Let’s look at some of the questions that are being increasingly asked.

Can we trust our leaders?

The chronic and profound failures of leadership that we’ve witnessed have allowed the perception of the leader to be diminished. As we explored in the Introduction, in the past 25 years the world’s leadership culture has shifted on its axis. It used to be an overwhelmingly male, heterosexual, patient, predictable, real, planned, white, long-term, Western-orientated, technology-leveraged, deflationary, structured, left-brained rational, broadcast, top-down, militarily symmetric world.

Now, leadership is operating in an inverted, unreal, impatient, inflationary, selfish, spiritual, irrational, gender-fluid, polysexual, asymmetric, strategically multipolar, everywhere-facing infrastructure, bottom-up, information-soaked, multi-racial, androgynous, fluid, rapidly moving, militarily asymmetric world.

Trust in all forms of leadership is at an all-time low. It is almost impossible to find any avenue of human endeavour where there is not an example of failure. At least, if our leaders are that bad, we can get rid of them. This, though, addresses the symptom, not the cause. If a sports team keeps failing, you don’t give up on the sport, you get better players. If the players are all poor, then you look at their training. That’s why we need leadership that analyses and parenthesizes and thinks long- as well as short-term. We need leaders that can join the dots. We need our leaders to be better, not just do better.

A truly mixed reality

Our love of the future probably reached its zenith in the 1960s, during the era of space flight. It all seemed possible. Food in a pill. Tiny computers. Weightlessness. A man on the moon was considered the height of technological achievement. Now, it’s not only the rationale of that mission that’s debated. In a post-truth world, there are many questioning whether it actually happened at all.2

As we explored in Chapter 1, the mixed reality environment created by technology is not just about augmented reality or 3D goggles. It applies to our daily lives. Our technology diminishes our presence in the here and now. How many times have you seen families or couples out for a meal where they are all staring at their iPhones? The internet disintermediates human relationships such as parenting, and governments are belatedly beginning to intervene.3

Once again, we confuse communication with conversation. We live in an age where the volume of communication has evolved beyond what many believe is efficient. When communication supplants conversation, we start to get insidious and persistent issues. If you can’t converse, you can’t resolve emotional problems, manage people or negotiate. The more experience of conversation we have, the better at it we get. We learn this at an early stage with our families. Is it so difficult to understand the recent rise of emotional problems among young people? Could the iPhone have anything to do with it? As we saw in Chapter 3, productivity increases began to fall the same year the iPhone was launched. These events may be connected.

Having embraced science and new technology for so long, there may be signs that the public are beginning to reject it. We mentioned the Center for Humane Technology in Chapter 6. The public have also become increasingly concerned about the science in genetically modified crops, cloning, fracking, gene editing and stem cell research.

Should we still work hard and save?

As we saw in Chapter 2 about economic behaviour, what used to be ‘good’, savings and thrift, has been punished by low or negative interest rates. The new moral good is the exact opposite – debt and consumption. This has led everyone from college students to presidents to question the very rules of the game. Society is now at war with the economic system itself because some are working on the old morality, some on the new. This is not a hypothetical or philosophical point. Leaders are widely perceived as mountebanks, deliberating conning the public out of their money.4

Add a little inflation to the mix and the net result is to punish those who live within their means and who put money aside. Today’s message is clear. If you want to save to ensure a life independent of welfare, the state will punish you for it, but if you’re feckless and become dependent, the state will give you money. By any standards, savers are citizens whom government and central bankers want to encourage. This, often at the same time as politicians were pursuing so-called austerity measures and punishing welfare dependency by cutting pay-outs. Why should anyone be surprised if this sort of economic moral inversion on this scale triggers insurgency? It would be irrational if you weren’t concerned about this.

Should we be patient and work together to get results?

As we established in Chapter 3, impatience is also encouraged and catered for, even expected. Now those with patience are dismissed as laggards or lacking in aspiration. ‘Everything comes to he who waits’ has become ‘Devil take the hindmost’. We can see this in rising staff-churn levels through the caring professions such as nursing, teaching, childcare and so on.5

We have also looked at how the average length of job tenure is declining. Former head of the US Federal Reserve Alan Greenspan said in his book The Age of Turbulence6 that when he started work in the 1930s, he could not perceive of a time when the average job tenure in the United States would become so short. He grew up in an age where employees were loyal to an employer and vice versa. The recent pensions scandals have also undermined confidence in employers. Even if employers could repay loyalty, it’s more likely they won’t even get the chance. New forces are at work that require new thinking.

Is education worth it?

Perhaps a better question might be: ‘Does education pay?’ Many students have begun to question whether the cost of a university degree is worth it. The truth is more nuanced. Some degrees will pay back.7 Others won’t. McKinsey found that 42 per cent of recent graduates are in jobs that require less than a four-year college education. Worse still, 41 per cent of graduates from the nation’s top colleges could not find jobs in their chosen field.8 US college graduates aged 25 to 32, working full-time, earn about $17,500 more annually than their peers who have only a high school diploma, according to the Pew Research Center.9 Is all this worth the average cost of $50,000 or £35,000? Thirty-seven per cent of graduates now regret going to college in the first place.10 Some students have even sued their universities11 because of the economic consequences of not getting the grades they wanted. Even Goldman Sachs,12 one of the biggest graduate employers, has questioned the point of a degree. Today, vocational training is paying more than a university degree. There are shortages of welders and mechanics. They are in demand. We should start treating vocational training with less disdain.

Writer Seth Godin has pointed out in his book Linchpin13 that education is currently configured for jobs that currently exist. By the time the education is complete, those jobs may have already gone away or changed.

Looking for a new domestic politics

Whether it’s inequality between the genders, which we heard about in Chapter 7, or the share of income in general, income inequality has become an issue in recent years. It is estimated now that the United States’ top 1 per cent of earners average $1.5 million a year and their share of average national income has risen to 22 per cent.14 This has led to calls for greater intervention to curb the excesses of the market. Writing in The New York Times,15 David Priestland said: ‘The West saw a Marxist revival in the 1960s, but student radicals were ultimately more committed to individual autonomy, democracy in everyday life and cosmopolitanism than to Leninist discipline, class struggle and state power.’ The rise of Momentum in the Labour Party has driven a more socialist agenda. Whether this leads on to Marxism and communism is debatable. It’s more likely to lead to greater state intervention or an urge to destroy the political system itself, which is probably what we’re seeing not just in the United States.

For the first time since the Second World War, Germany has a far-right party, the Alternative fur Deutschland (AfD), in the Reichstag. Jewish groups are already protesting that the AfD has a place on the board of the foundation for the national Holocaust memorial in Berlin.16 Marine Le Pen’s National Front party took over 30 per cent of the 2015 vote versus Emmanuel Macron.17 In Austria, the Freedom Party18 is now in government as well. Whether this is a return to old polarities, it’s difficult to say. It looks as if voters want to experiment with something entirely new. Large numbers of US voters were genuinely split between the political extremes of Sanders or Trump, according to research.19 What’s clear is that the political system isn’t working for people as it once did, so they’re willing to try alternatives. In essence, though, the problems they face are more technical and cultural than political, because we can’t uninvent the Boeing 747, the internet and the iPhone.

Now our friends spy on us, too

The great inversions are not just related to domestic politics. Geopolitically, the rules have been stood on their head as well. The whole purpose of diplomacy is to patiently manage relations within a context, within a system of known rules and protocols and agreements. Today, we’re witnessing a breakdown of trust in the system itself. Even policymakers whose entire job it is to support and defend the system are not sure it’s viable any more.

We see more and more blatant challenges to the system, from grass roots movements to methods being used by states that used to be considered out of bounds. For example, the film Us versus Them, where students at Middlebury College stop a lecturer by shouting him down and threatening violence. The young may just prevent what they see as ‘the elites’ from operating. Impatience erodes trust, and we’re seeing this replicated at the geopolitical level, too. For example, all the major industrialized nations are now openly wiretapping each other and trying to steal secrets. What governments do, companies follow. This means that companies are often trying to steal intellectual property, covertly assisted by government agencies. This could be because everyone wants information in real-time.

As an aside, wiretapping is a thing of the past. Technology has removed the need. Now we find that any smart item that is connected to the Internet of Things is constantly broadcasting our every word and movement anyway. We were impatient to control the technology. Now the technology is controlling us.

Inversion and alignment

If it’s true that the world has become inverted, then it’s also true that nations that used to be opposites can become similar. Let’s take East and West. We used to think that the political models of the United States and China were different, if not opposites. Maybe they are more similar now. A key leadership task is to look for these new alignments. Table 8.1 provides some other examples.

Table 8.1 Examples of commonality between the United States and China

|

United States |

China |

Commonality |

Spend on infrastructure |

Spend on infrastructure (One Belt, One Road) |

Both seek to create GDP and garner votes |

Challenge the liberal international order by tearing it down – refusing to fund the UN, for example |

Challenge the liberal international order by replacing it with One Belt, One Road. Create new institutions such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) |

Both talk of leading the system from a position of strength |

Promote the interests of domestic workers |

Promote the interests of domestic workers |

Obvious vote winner |

Use US materials |

Use Chinese materials |

Obvious vote winner |

Build a wall to keep troublemakers out |

Build a (digital) wall to keep troublemakers out |

Putting their voters first |

Spend on defence |

Spend on defence |

Both want an economic stimulus that can be pursued without approbation |

Lead from strength |

Lead from strength |

Obvious vote winner |

Control media content by restricting or bypassing traditional media |

Censor media content by restricting or bypassing international traditional media or limiting access to the internet |

Message control |

Reward only ideological allies |

Reward only ideological allies |

It’s about power |

Loss of civic trust (witness allegations of abuse of power such as illegal wiretapping) |

Loss of civic trust (witness capital flight and rising dissent) |

It’s about loss of trust in the entire system, not just the policies or personalities |

Despite many commonalities, Table 8.1 still puts the United States and China on different and potentially conflicting paths. The question is, can both the United States and China’s leaders fulfil the promises they have made to their citizens simultaneously? History suggests the United States can. China does not yet have this history. It, too, is suffering from the inversion. It used to be a low-wage economy, but that is no longer true. It used to save, but that proved ill-advised. It once restricted families to one child only. That was also reversed.

Is success always rewarded?

There’s a growing sense that leaders at the top of organizations are increasingly rewarded for failure20 or over-rewarded when others are suffering. This is evidenced by the size of the pay-outs they receive when being fired. For example, in the downturn at SeaWorld after the film Blackfish, 311 workers lost their jobs due to cost-cutting measures. CEO Jim Atchison resigned and received a £1.7 million payoff. According to The Washington Post,21 his severance pay was equal to twice his base annual salary, plus his targeted 2013 bonus. The company also confirmed that Atchison would continue as the company’s vice chairman and as a consultant on international expansion.

Is it only the bad guys who use torture?

Ever since the Abu Ghraib22 prison scandal in 2006, it’s been clear that abuse and torture have been used by the Western militaries and their intelligence agencies. Despite the US Senate banning their use in 2015,23 accusations have persisted. In January 2018, a human rights campaigner, Nils Melzer, the UN special rapporteur on torture, accused the US government of using it in Guantanamo Bay.24 The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) has consistently pointed out that the use of torture is not only illegal and immoral but also ineffective.25 And yet, the public seem to support torture now more than ever.

Does morality matter?

Morals, like any other set of laws, are not just good for their own sake or nice to have. They can only be upheld with the consent of the majority they seek to govern. When atomized, individuality becomes the majority behaviour and thus consensus becomes harder. This partially explains the breakdown of confidence in the system of rules that has been in place over decades. Why does this matter to leaders? Simply because leaders need to motivate their teams. If they do not understand the ‘rules’ or even their expectations, they cannot be successful.

To understand this notion further, we can look at the works of German philosopher Immanuel Kant. His theory, developed from Enlightenment Rationalism, was that the only intrinsically good thing was intent. This would, for instance, include the duty not to lie. Today’s equivalent is a demand for authenticity. Failure to align actions with image is fatal in the new world of transparency. At the heart of this notion is justice. To win hearts and minds, leadership needs to be seen to be just. Without this there can be no trust. It would seem an odd assertion that leadership needs to do good. All leaders would automatically assume that people knew that was the case. For all the reasons that we’ve outlined in this chapter, that assumption has been challenged. There are no shortcuts; leaders must earn trust all over again. If people don’t trust their leaders, they will not trust the future either.

Whatever happened to the future?

In the 1950s and 1960s, the future looked exciting. There was ever-improving wealth, health, standards of living and social freedom. Many people became home owners and went to university for the first time. Now, in the West, children do not expect to be wealthier or freer than their parents. It is impossible for them to own property. What’s more, successive governments have eroded pensions and long-term wealth. This fear of the future is reflected in popular culture. Many films set in the future are entirely dystopian. The various themes include scenarios where computers subvert human relationships (already true to some extent), they take over and force humans to their will (already true to some extent), they impoverish and destroy careers (already true for those at the bottom) and they take over as emotional partners (on its way26).

The opposite is true of nostalgic culture. Productions such Dunkirk (2017), Darkest Hour (2017) and The Crown (2016) reflect a utopian past. This was an age of grace, of unity, of pride, identity and belonging. Events such as vintage air shows and the Goodwood Revival have raised nostalgia to sell-out levels. At the latter, people dress up and browse replica stores from the 1950s and 1960s, they watch vintage car racing and Second World War aircraft fly past. We’ve also seen a revival of ‘festivals’.27

When we fear the future and glamorize the past, it’s a signal that we are trying to hang onto an image of reality that may already be out of date.

A new multipolar world with walls

Another element that previous generations would not recognize is strategic. Then, you knew who the enemy was. They wore a different uniform, spoke a different language, lived in a different country. Now the ‘enemy’ is all around. They look like us, talk like us and live among us. The world no longer has two poles, it has many. As discussed in Chapter 5, the world used to be coming closer together, with walls coming down. Now it is divided and getting more so as walls go up. What we expected to be a linear relationship with ever-greater integration and cooperation has been reversed.

Globalism is over

One view is that the public rebellion against globalism means that leaders can no longer simply assert that more trade is in everyone’s best interests. The Berlin Wall came down in 1989, which was a long time ago. Leaders may still be thinking we live in a world where inflation fell or disappeared because so many new workers were willing to work for even less back then. In that world, we no longer had to spend as much money on defence because the bipolar world disappeared, leaving us with a ‘peace dividend’ that could divert capital away from nuclear weapons and towards more productive investments. In the old post-Berlin Wall world, it was obvious to everyone that the flow of capital and human capital across borders would benefit everyone.

In today’s world, these are no longer universally shared assumptions. Yet people everywhere want to do more business, sell and buy more goods and services. Everyone is trying to figure out how to go where the growth is. Workers are no longer willing to work for ever-lower wages. Trade is becoming more global than ever as the Chinese build production facilities in the United States and Europe and the Americans invest globally. New walls are going up even as the internet tears the old ones down. The internet is paradoxical. It can close the mind while expanding trade. It can speak of the end of globalization, even as it dramatically redefines it.

When we step back and survey the landscape, it becomes ever clearer that there are many inversions of our values. We can summarize these ‘inversions’ as shown in Table 8.2.

Table 8.2 The LAB table of inversions

|

‘Good’ used to be… |

‘Good’ is now… |

‘We the People’ |

‘Me the People’ |

Communities/groups |

Groups and groupthink are bad. Individuality is more admired |

Thoughtful, clear, measured responses |

Twitter at speed, jargon and emojis |

Long-term careers |

Work gigs, internships, ‘experiences’, fast turnover, side hustles |

Simple truth |

Spin, messaging, weaponized information. Fake news |

Study |

Hacks and shortcuts |

Education |

Work experience |

Debate |

No-platforming, anger, dictums |

Restraint |

Bingeing and excess |

Saving |

Spending |

Buying |

Sharing |

Dress up |

Dress down |

Etiquette and protocol |

Huddles and hang-outs |

Marriage and commitment |

Promiscuity and Tinder |

Free speech |

Censored speech: political correctness |

Moral probity and decorum |

Recklessness |

Formal education and scholarly sources |

Street. Wikipedia. YouTube. Teach yourself. Formal education declining in value |

Patience |

Immediacy |

Anonymity, modesty |

Celebrity, attention |

Taxation |

Tax avoidance |

Conversation |

Communications |

Trust |

Cynicism |

Quality |

Disposable |

Innovation |

Iteration |

Conclusions

At a superficial level, the world appears unchanged to many leaders. It has, though, undergone arguably some of the most profound technical, commercial, cultural, social, behavioural, moral and economic changes ever. This has not just changed a few things, it has changed virtually everything. It has not been a small change. It has completely upended and inverted principles, values and rules which have been unchanged for centuries. This has left our leaders speaking in tongues. It has left them disorientated and situationally bereft. The change has been so far-reaching that it has left them parroting defunct lines such as ‘all the jobs are going to China’, which just confirms they are out of touch. It has also made them espouse ideas that are fundamentally hypocritical or nonsensical. For instance, we want you to be independent, but we will punish you for being so. The greatest irony of all is that the great age of inversion has had its most enduring effect on leaders themselves. Rather than being seers of events, they have become victims of events.

Endnotes

1 Pinker, S (2015) The Better Angels of Our Nature, Penguin, New York

2 http://www.newsweek.com/fake-apollo-moon-landing-photo-claims-show-proof-mission-was-hoax-716221

3 https://www.politicshome.com/news/uk/political-parties/conservative-party/news/93500/culture-secretary-proposes-social-media-time

4 http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/politics/criminals-and-corrupt-politicians-steal-1trn-a-year-from-the-worlds-poorest-countries-9707104.html

5 https://www.nursingtimes.net/news/workforce/call-for-urgent-action-to-halt-rising-social-care-staff-turnover/7021589.article

6 Greenspan, A (2008) The Age of Turbulence: Adventures in a new world, Penguin, New York

7 https://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21600131-too-many-degrees-are-waste-money-return-higher-education-would-be-much-better

8 https://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21600131-too-many-degrees-are-waste-money-return-higher-education-would-be-much-better

9 https://www.economist.com/news/united-states/21600131-too-many-degrees-are-waste-money-return-higher-education-would-be-much-better

10 https://www.forbes.com/sites/nickmorrison/2016/08/09/if-theres-one-thing-millennials-regret-its-going-to-college/#3faa788a3536

11 http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/11/21/oxford-graduate-sues-university-1million-did-not-get-first-class

12 http://money.cnn.com/2015/12/09/news/economy/college-not-worth-it-goldman/index.html

13 Godin, G (2011) Linchpin: Are you indispensable? Portfolio, New York

14 https://inequality.org/facts/income-inequality

15 https://www.nytimes.com/2017/02/24/opinion/sunday/whats-left-of-communism.html

16 http://foreignpolicy.com/2018/01/15/germany-doesnt-have-a-playbook-for-a-nazi-sympathizing-parliament

17 https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2017/05/07/world/europe/france-election-results-maps.html

18 https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/dec/18/the-far-right-freedom-party-is-joining-austria-government-how-do-you-feel

19 https://www.cnn.com/2016/02/08/politics/new-hampshire-primary-independent-voters/index.html

20 https://www.forbes.com/sites/nathanielparishflannery/2011/10/04/paying-for-failure-the-costs-of-firing-americas-top-ceos/#5ee17a444bc7

21 https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/morning-mix/wp/2017/08/30/investors-say-seaworld-lied-about-business-downturn-after-orca-outcry-now-feds-are-investigating/?utm_term=.9fc9801df27d

22 http://www.latimes.com/nation/la-na-abu-ghraib-lawsuit-20150317-story.html

23 https://www.cnn.com/2015/06/16/politics/senate-torture-bill-cia/index.html

24 http://www.newsweek.com/torture-used-us-military-guantanamo-bay-despite-being-banned-un-says-747373

25 https://www.justsecurity.org/35816/icrc-survey-torture-glass-two-thirds-full/

26 https://venturebeat.com/2017/11/14/meet-the-robots-caring-for-japans-aging-population

27 https://www.telegraph.co.uk/travel/destinations/europe/united-kingdom/articles/Britains-best-vintage-festivals-Goodwood-Revival-and-more