CHAPTER NINE

The Global Leaders’ Narrative

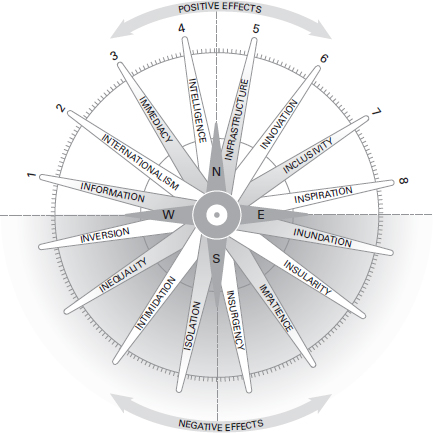

The Kythera is a tool to help leaders navigate complexity. It shows the duality of the world we live in arranged across eight ‘spokes’.

The spokes used in the Kythera – information and its overload, economics and its effects, behavioural changes, geopolitics, technology, gender and the generally inverted nature of things – provide the key challenges to leadership.

The first task of all leaders is to recognize that uncertainty is the primary characteristic of the 21st century. Leadership needs to prepare for this by keeping a wide parenthesis of thinking. This is for three main reasons: it allows them flexibility; it allows the pursuit of unity; and, finally, because ‘opinionated certainty’ and the rigidity it engenders are a hallmark of mediocrity.

The second task is to recognize the deep paradoxes illustrated by the Kythera. The pull towards polarity is a centrifugal force constantly offsetting leadership efforts. Some days, good leadership will feel it has achieved nothing, but it has at least offset the trend. Good leadership improves on the status quo; however, sometimes, it may just maintain it.

Leadership must see the limitations of the left-brain process. We cannot analyse our way out of every problem. We need our synthetic skills to contextualize and parenthesize. We cannot consider binary outcomes any more. Only a new global leadership approach based on situation fluency will help. Leadership needs to:

- Learn the lessons of the past

- – Weak leadership lacks imagination, not analysis

- – Overconfidence is a problem

- – The dangers of ‘big is better’ thinking

- – Lessons from a general

- – Guard against short-termism, it can destroy everything

- – Control the information flows, before they control you

- Study the present

- – Study geopolitics and the physical world

- – Guide capitalism, don’t guillotine it

- – Consult conspicuously, communications are expected

- – Know your team, see the gaps

- – You cannot defend yourself with the facts alone

- Prepare for the future

- – Culture eats strategy, so lead with values

- – Lead by values

- – The ‘J’ word still matters more than anything

- – Failures are more visible and often due to fear

- – Use trust to kill fear, otherwise it will kill innovation

- Commit to the leadership spirit

- – Leadership is more than management/Leadership can always be better

- – Serve the widest community

- – Cultivate inclusivity, it breeds unity

- – No alternative but to embrace the future

- – Faith matters

- – Situational fluency

- – St Augustine of Hippo

Learn the lessons of the past

Weak imagination undermines leadership more than weak analysis

In addition to providing a guide to the future, we have catalogued leadership failures from the past in this book. They share a common denominator. Leadership fails when there is a lack of imagination. Problems happen when there is an inability or unwillingness to envisage alternative possibilities. Being as wrong as everyone else is no longer an acceptable excuse for a leader. When the financial crisis happened in 2008, the conditions for division were established. The resulting revelations about conduct destroyed lives, brands and confidence for a whole generation. It wasn’t weak analysis alone that caused this. It was also a collective failure of imagination.

Overconfidence is a problem

As we established in Chapter 7, correlating competence with confidence is a prime cause of leadership failure. Our leaders often come from specialist backgrounds, with drill-down skills, steeped in heavily analysed data. The Western Reductive technique does not teach imagination. Our leaders are therefore weakened rather than strengthened by the specialisms through which they pass on their way to the top. This leads us to clues, but not necessarily conclusions, about the reasons for collective failures of leadership. The tendency to overconfidence based on quantitative data alone is a habitual problem in some, but not all, leaders. Others, of course, have too wide a perspective and too little grasp of detail. Balance is the key.

Aspirant leaders are to be encouraged because these ladder-climbers inspire and show the way. We need more of them, because what they represent is as important as what they do. They also tend to learn more on the way. There are not nearly enough leaders who have climbed all the rungs and have a catholic competence in many areas.

The dangers of ‘big is better’ thinking

Quantitative thinking alone ultimately leads to a fixation on numbers, for example sizes and volumes. Seldom does an organization get bigger as well as better. Making an organization better, however, does allow it to grow. Size is too often taken as an indicator of success, when, in reality, it could be seen as an indicator of poor service, lack of control and zero imagination.

Lessons from a general

There is now a growing pressure for better leadership. This is coming as much from movements such as #timesup and #metoo as it is from voters, shareholders and other stakeholders. There is a better chance that leadership will wake up to the catalogue of collective failures when they are as concentrated as they now are. We can draw lessons from past efforts to challenge leadership.

Kurt von Hammerstein-Equord was a German general famous for being an ardent opponent of Hitler and the Nazi regime. He said that he divided his leaders into four groups: ‘There are clever, diligent, stupid, and lazy officers. Usually two characteristics are combined. Some are clever and diligent – their place is the General Staff. The next lot are stupid and lazy – they make up 90 per cent of every army and are suited to routine duties. Anyone who is both clever and lazy is qualified for the highest leadership duties.’ He said this was because that type of leader ‘possesses the intellectual clarity and the composure necessary for difficult decisions’. He finished with a warning to beware of ‘anyone who is stupid and diligent’, because this sort of leader ‘will always cause only mischief’.1 This approach is echoed by Warren Buffet, who chooses people based on three criteria: ‘You’re looking for three things, intelligence, energy, and integrity. And if they don’t have the last one, don’t even bother with the first two.’ Today’s leaders need to have the integrity to know that blindness to reality is no longer an acceptable leadership trait.2

Guard against short-termism, it can destroy everything

The fixation on speed in all things has become an obsession. It has undermined patience, planning and personal relationships. It has also created the illusion of speed, rather than the actuality of it. Good leaders must spend time planning, thinking and patiently preparing. The imagination to foresee danger comes from quiet contemplation and conversation.

Control the information flows, before they control you

Churchill3 said: ‘First we shape our buildings. Thereafter they shape us.’ The same principle applies to how we use our tools. The internet is perhaps the greatest tool mankind has ever created. It is now beginning to shape our behaviour, in many areas making us more selfish, greedy and impatient than ever. Leaders must be those who unite people in a common cause. To that end, they need to bring people together through qualitative as much as quantitative thinking. In a great digital age, big data and technology will dominate our lives like never before. We will become much more efficient. We’ll be able to measure just about everything much more accurately. This left-brain process of compare, contrast, analyse will be everywhere. This, however, is a process that notices difference and comparison. It’s a tool for separating one thing from another. The more we subject people to this process, the more we divide them from a common humanity. The technology storm is not helping us get a more holistic approach. The more specialized we are, the more atomized we become. We do not hear and we do not see beyond our narrow view. It’s difficult to see the horizon when you’re buried in data.

Study the present

Study geopolitics and the physical world

As we covered in Chapter 5, the physical world is changing. Infrastructure development is changing the very fabric of our world. This is worthy of constant study. The world is not just made up of changes occurring in cyberspace. It is kinetic as well. There are airports, canals, roads, railways and major ports being built all over the world, often in places where there has been little development. It is exciting and full of opportunities.

Guide capitalism, don’t guillotine it

Many today are so angry and disappointed that they are prepared to throw out capitalism as a whole. However, perhaps the problem is not the system but the way it’s been managed. It’s important, though, to remember that capitalism and democracy are voluntary. Drivers stop at red lights because they agree to. When elites appear to be above the rules, it creates discontent. The system can easily fail if no-one believes they should follow the rules because those at the top won’t. The anger that many clearly feel isn’t just anti-capital rage. It arises from the realization that its benefits are not fairly shared and its rules are defied by those at the top. The rules that govern capitalism are based on the assumption that they serve the interests of everyone and not just those of a few.

The private sector needs to evolve its approach. Its boardrooms need to lead the way. We need to see Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) mandate qualitative statements about the longer term, the community and welfare.

Consult conspicuously, communications are expected

It will no longer be enough to research views. Leaders will need to be seen to be consulting and they will need to actually consult. Listening (and appearing to listen) will really matter. All business is at its best when it realizes a social as well as commercial narrative. For capitalism to succeed, it needs permission, and that will only be granted when its benefits are shared. In a full employment economy, ‘permission’ leadership prevails. Leadership must be sensitive to how it looks and communicates. The fundamental communications equation is:

Frequency × duration = retention

The longer and more often something is repeated, the more it is recalled. This is important when leadership has to cut through the inundation to be heard (see Chapter 1).

Know your team, see the gaps

Knowledge of the world, the subject matter and the news may help, but the leader without knowledge of their team is helpless. It is important to know the ‘1-in-10,000 skill’ each person has. The more the leader knows the team, the more potential can be seen in all of them.

You cannot defend yourself with the facts alone

In most leadership groups, there’s an abundance of people who defend shareholder and stakeholder value with the truth. There’s someone that deals with finance and numbers (the Chief Financial Officer). There’s someone dealing with the statute and precedence of the law (the General Counsel). These professionals deal with the facts. Working to the letter of the law, you may be able to prove you’re not breaking any tax regulations, but that will not change the perspective if you’re not operating within the spirit of the law. Offshore tax havens may be perfectly legal, but they do not look it. You may not actually be a drug cheat in sport. If, however, you’re using a substance that is not normal yet not banned, but nevertheless has a beneficial effect, the perception may be of cheating. The optics matter because, as we have shown, opinions have become more important than facts.

Prepare for the future

Culture eats strategy, so lead with values

The modern leader must be aware that they can’t ‘do’ values. They can only ‘be’ them. It’s easier to be impatient with what someone does. This is why leaders need to have a ‘to be list’, as well as a ‘to do list’. It is one of the hardest tasks faced by young leaders. They want to ‘do’ too much. This leads to inconsistency, stress and short-termism. They should not feel ashamed of doing less, first, because it allows for empowering delegation and teamwork, and second, because it means they can concentrate on what they, and they alone, can be. This is a variation of the ‘management by exception’ rule. Leaders need to be human beings, not human doings.

Lead by values

What are the values of the team and the organization? What should they be? The values will always tell you what the team is capable of (for good or bad). Is it dedicated, committed, honest, diligent, imaginative and energetic? What values does the team admire? Has anyone ever asked? Values matter because they can unify teams at a wider level irrespective of their individual differences.

The ‘J’ word still matters more than anything

However we define ‘judgement’, it is still the most highly sought-after leadership skill. It remains both a science and an art combined. Situational fluency is important to it and so is timing. It involves judging the mood and sensing the environment. It’s almost impossible to teach or even to define, but it remains the quality that separates the leadership candidates.

On 29 July 2006, at a meeting of The World Future Society, Dr Bruce Lloyd, Professor of Strategic Management at London South Bank University, presented a paper called Wisdom & Leadership: Linking the Past, Present & Future.4 It is one of the best papers ever written on leadership thinking. He pointed out that:

Wisdom is the way we incorporate our values into our decision-making process and it is our values that determine the way we define that critical word ‘quality’. The word ‘quality’ can also be seen as another way of distinguishing process from change. Not all change is progress and it is our values that ultimately determine our priorities. It is these priorities that then become the criteria we use to distinguish between change and progress.

Failures are more visible and often due to fear

The numerous and visible examples of failure should damn all leadership. There are great leaders out there and the LAB met many of them. Of course, it’s in the nature of things that no-one notices good leadership, because disasters simply don’t happen. For this reason, good leadership needs to celebrate the routine, the reliable and the consistent as well as the extraordinarily good.

Change accelerates as it moves towards leaders. When people are fearful, knowledge or planning coming from leadership can be empowering. Weak leadership, though, is often exposed because it fails to evolve new ways of thinking. This causes it to be paralysed in the face of change and the resulting fear is contagious. Much of navigating a changing world has to do with managing fear – fear of the unknown, fear of failure and fear of embarrassment. This does not always manifest as fear. Most often it appears as intransigence or inertia. Neuroscientists believe that fear makes people behave less intelligently and makes them less likely to move from their comfort zone. This reaction is known as the ‘amygdala hijack’. This was a term coined by Daniel Goleman in his book Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ.5 Where there is a fight, flight or freeze situation, the rational brain is effectively over-ruled. When the amygdala perceives a threat, it can cause an irrational and destructive reaction. This is characterized by three signs: strong emotional reaction, sudden onset and post-episode realization, if the reaction was inappropriate.

Use trust to kill fear, otherwise it will kill innovation

Innovation can be a delicate flower. It can be killed at the point of conception. Ideas will only be advanced if it is felt that they won’t be judged harshly. It is difficult for some to come forward with ideas. Leaders must create a level playing field to allow as many ideas as possible to come forward. Trust must be built over time. This means repeatedly applying ‘Safe Enough to Try’ rules so that risk can be encouraged without killing creativity.

Understand how skills and values have changed

If there’s one great strategic take-away from this book, it’s that leadership skills have changed fundamentally over the past 25 years. Table 9.1 is a distillation of key leadership skill changes that LAB delegates felt were important themes.

Table 9.1 Changes in key leadership skills

|

20th-century leaders |

21st-century leaders |

Operated to the letter of the law |

Operate to the spirit of the law |

Won at any price |

Win fairly |

Managed in the interests of a few |

Manage in the interests of the many |

Applied more logic |

Apply more imagination |

Maximized strategy |

Maximize culture |

Created an androcentric culture |

Create androgynous cultures |

Planned for either/or |

Plan for both/many scenarios |

Supported ‘the system’ |

Smash or adapt ‘the system’ |

Made binary decisions |

Allow quantum ‘super-position’ |

Used black and white |

Use the full palette/rainbow |

Used labels and certainty |

Plan for uncertainty and ambiguity |

Predicted |

Prepare |

Researched science and facts |

Use opinions and pose questions |

Concentrated more on doing and objectives |

Concentrate more on being/values |

Understood, expected, knew |

Expect it to be stranger than they think |

Expected it to be predictable |

Expect unimaginably good or bad |

Used business books |

Use theology and philosophy books |

Valued dynamism and immediacy |

Value patience and listening |

Prioritized youth education |

Prioritize lifetime education |

Stopped/detected/prevented failure |

Embrace/understand/allow failure |

Wanted big and bigger |

Want better |

Owned assets |

Share assets |

Operated rigid resistance |

Be fully flexible |

Coped with events |

Have a process to anticipate change |

Wielded authority |

Empathize |

Saw work as work |

See work as play |

Managed adult behaviour |

Manage infantile behaviour |

Used judgement and intolerance |

Use love and empathy |

Exercised control |

Ask for permission |

Centralized |

Distribute |

Learnt the lessons of history |

Embrace the future |

Were ‘waterboarded’ busy leaders (see Chapter 1) |

Are open and available |

Were serious |

Are playful |

Saw the board as compliance |

See the board as a justice forum |

Saw the board as a congregation/club |

See the board as a conscience |

In the future, changes clearly show the scale of the transformation. Leadership which was once rigid, fixed, firm, traditional, legacy, slow and judgemental, in the future will demonstrate flexibility, agility, imagination, values and open-mindedness.

Commit to the leadership spirit

Leadership is not just management

H G Wells said: ‘Human history becomes more and more a race between education and catastrophe.’6 The more change there is, the more important our learning and leadership become. That’s the only way we have any chance of being able to equate change with progress. So, if we want to have a better future, the first and most important thing that we must do is improve the quality and effectiveness of the learning.

The world has excellent economics, business, management and military schools. Leaders also learn on the job, as do politicians. Strangely, there is still one job that requires no formal training, that of political leader. That should change. The central problem for the institutions as a point of provenance for leaders is that they were shaped by Western Reductive methods. They overwhelmingly teach how to analyse. Leaders end up in generalist roles, but they get there by being a specialist. Orchestra conductors are generally not expert soloists, but they know how to inspire performance.

Leadership is not perfect, but it can be better

We must be realistic about leaders. It’s OK for them to take risks. In fact, all progress depends on it. We can be too quick to punish them as individuals for innocent failure. The unstable toddler gets up partly by instinct but partly through encouragement and love. What is repeated failure, though, except the parent of success? As Kipling says in Tommy:7 ‘An’ if sometimes our conduck isn’t all your fancy paints, Why, single men in barricks don’t grow into plaster saints.’ Leaders of organizations will never be the acme of behaviour. They should not be held up as paragons of all virtue. It’s the leadership team that matters. They can be trained to work together. We can teach them to be more patient and think longer-term. We can reward stability, consistency and teamwork.

Serve the widest community

For many, the future is frightening. Without change, we face the dark side of the Kythera. With increasing levels of income inequality, we could head backwards to division, violence, war or a new type of feudalism where beneficiaries ring themselves first in gold and then in steel. The place for leaders is not behind bars in any context. The community is the provenance of the leaders, whether they recognize it or not. Leadership is not just something leaders do at work. Their leadership of social causes will also highlight their moral leadership. They must emanate light, faith, positivity and hope and be rooted in the people they serve. There will be much at stake and very high risks. The higher the rank, the higher the risk and the higher the trust we require from them.

If leaders want to demonstrate their contribution to the community, then it needs to be done on a genuine and sustainable basis.8 Responsible Business Conduct (RBC) is replacing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). The problem with the old CSR model is that it is often associated with voluntary philanthropy and as an add-on external to core business operations. There is a discretionary element of this which is unlikely to be enduring. No amount of discretionary donation to any charity would change the perception of any of the wrongdoers listed in this book.

Cultivate inclusive thinking, it breeds unity

All teams need a diversity of thinking, not just a diversity of people. We must guard against simplistic solutions that swap one prejudice for another. If we condemn leaders for being ‘pale, male and stale’, then we swap one skin, gender and age prejudice for another. Masculine skills do not reside solely in men, nor feminine skills in women. We need to be thinking less about defining people by skin colour and gender and more about the values and skills diversity brings. If we want more female thinking in leadership, then we need to make our cause more than just about a single gender. It’s about balance and shared goals such as modernity, aspiration and representation. All genders can focus on these objectives. It is not about men or their shortcomings. If one gender wins at the expense of another, then everyone loses irrespective of who’s victorious.

Inclusivity is all about democracy. Free markets and democracy walk hand in hand. Democracy, at its heart, is about sharing – sharing resources, sharing wisdom and sharing hope for the future. Democracy harnesses resources to make more resources. It does this because it harnesses the individual. The more democracies, the more the resources we can share. At the heart of this is a belief that the more we give, the more we receive. This is the essence of leadership.

We cannot be blind to the differences, but let us also direct attention to our common interests and to the means by which those differences can be resolved – through leadership. We cannot end our differences, nor should we. Democracy and diversity should be synonymous. Of course, leadership is not a democracy, but it’s better when it is. Democracy is not just an idea that we stick to occasionally when it suits us. Brexit, for instance, might not be to everyone’s taste, but we believe in democracy enough to put those with whom we disagree in power. This is democracy in action. Democracy is something that is shown. Not something that is told.

Some lament how divided the democracies are. They point out that never before have there been such sharp divisions in opinions. They say this as if it were something to be apologized for. As if, somehow, division were a weakness. There are many parts of the world, however, where there is no division or difference. This is in no way a demonstration of strength. Quite the contrary in fact. If an idea isn’t strong enough to withstand the opinions of others, then it is no sort of idea at all. Ideas are made stronger by disagreement, not vice versa.

So, let this be an abiding thought. When democracy is challenged by those who disagree with it, let that challenge make it stronger. Whether it be Brexit or domestic politics or our new approach to humanitarian aid. Because through it, we demonstrate our commitment to share democracy and our willingness to share the future. When we feed democracy, we feed inclusivity, we feed the future and we feed leadership.

No alternative but to embrace the future

There is no way home to some Ambrosian land where things were better. To hear some, you’d think the whole 21st century was the wrong exit from the motorway, where they just want to find a way back to the 1950s. When faced with the opportunities, it is a chance for each of us to return to our youth and embrace it with simple mindfulness and joy. We can gorge on nostalgia by the kilo, but we’re better served by a child’s appetite for the future. We cannot uninvent the modern world – unplug the internet, ground all the 747s, deny individualism. A transcendent quality of Marxism was its reliance on group identities. There can be no return to that. Jung recognized that the only way to reach individual potential was through what he called Individuation.9 The internet offers this potential if our leaders are able to meet the challenge.

Faith matters

How did we end up here? We still rely upon the same leadership institutions (often run by alumni) educating on and issuing the same leadership credentials. We have met a crisis in Western Reductionist thinking with yet more of the same. It’s almost as if we thought we could cure obesity with yet more food. These institutions do not teach divinity. They teach leadership as they know it. They are not pastoral, nor ecumenical, much to their detriment. Leadership is as much about faith as it is about finance. The institutions know the importance of this. Leaders should be aware of the spiritual, emotional and physical welfare of their teams. They and their teams would be the better for it.

The importance of situational fluency

The world has changed so far, so fast, as to completely disorientate the unwary. There have been repeated failures, creating perhaps the worst crisis in leadership since the world wars. We catalogued these in Chapter 8. There are many reasons for this. Structures became big and unwieldy, encouraging a lack of personal responsibility, even a dereliction of diligence. There was an over-reliance on Western Reductionism and left-brain thinking, overconfidence (and under-skilled people at the top) and an abundance of resource brought by technology in information. Above everything, leaders lacked a situational fluency to be able to see how events might move in several dimensions.

St Augustine of Hippo

Where will we find this new leadership spirit? This book is about the spirit of leadership, so it’s fitting to close it with the words of St Augustine of Hippo: ‘Don’t you believe that there is in man a deep so profound as to be hidden even to him in whom it is?’10 Humanity’s future is a darkened path. Leadership’s job is to be the beacon that illuminates our way. Only a new approach can ensure that light shines brighter than ever before. Leaders will have to open their hearts, as well as their minds, to find it. When they do, all humanity will follow.

Endnotes

1 Enzensberger, H M (2009) The Silences of Hammerstein (trans M Chalmers), Seagull Books, New York, p 87

2 https://www.fs.blog/2013/05/warren-buffett-the-three-things-i-look-for-in-a-person

3 https://www.standard.co.uk/comment/comment/rohan-silva-take-a-lesson-from-churchill-in-rebuilding-new-housing-estates-a3153271.html

4 http://www.wisdompage.com/blloyd02.html

5 Goleman, D (1996) Emotional Intelligence: Why it can matter more than IQ, Bloomsbury, London

6 Wells, H G (2017) The Outline of History, CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, https://www.createspace.com/diy

7 http://www.kiplingsociety.co.uk/poems_tommy.htm

8 https://medium.com/@OECD/2016-corporate-social-responsibility-is-dead-what-s-next-60d22fee8bad

9 http://jungiancenter.org/components-of-individuation-1-what-is-individuation