To understand why the best hunters expend great energy and take daily risks to help provision an entire band of mostly nonrelatives, Alexander’s selection-by-reputation theory appears to offer considerable explanatory power. First, as Alexander suggests, the cooperative sharers are making large reputational gains as good citizens because of their beneficence, whereas the opposite holds for selfish bullies and equally selfish cheaters and thieves. Second, as I’ve added, free-rider suppression functions as a major selection agency. This means that seriously problematic bad guys will suffer additional fitness losses owing to potentially brutal group punishment. Keep in mind that often such active punishment comes as a reaction to a longstanding pattern of rule breaking, which means that negative reputational choices are involved as well.

Basically, the selection-by-reputation model is keyed to how people’s viscera—and also their conscious calculations—respond to unusually attractive or unattractive social characteristics of others, and this can be a complicated matter when altruistic generosity is at issue. We saw with Nisa that she was actually criticized by her husband for being too generous, and when I asked my colleague Polly Wiessner about this, she told me that in general Bushmen who are overly generous in distributing food are considered to be poor partners because they are “wasting” resources. (A close analog in our own culture would be a compulsively generous big shot who squanders the family budget by repeatedly buying drinks for everyone in the bar.) On the other hand, people with really stingy social reputations are cordially disliked by the Bushmen. Thus, as far as Bushman reputations go, there can be too much altruism, which bothers partners, as well as way too little, which seriously bothers the entire group.

In analyzing the interpersonal attractions that lead to superior cooperative partnerships, we must also consider emotions like sympathy that lead to generosity, as opposed to “altruism,” which as the term is being used here merely involves a measure of beneficence as this affects gene frequencies. The problem is that direct evidence for generous feelings that underlie giving is seldom provided in ethnographies. This is the case even though hunter-gatherers universally think in terms of golden rules that are designed to reinforce people’s tendencies to be sympathetically responsive to the needs of others. The sympathy variable definitely is ethnographically elusive. But in my opinion it is extremely important,1 and fortunately we have one systematic field study in which it has, in effect, been measured with its reputational effects, and also another study of marriage choices in which the social benefits of being an empathetic partner are strongly implied.

Selection-by-reputation theory was developed by Alexander with people like the Bushmen in mind, but even for the well-studied Bushmen, there’s no research that focuses directly on sympathetic generosity and its social effects. Fortunately, there’s one fascinating systematic investigation that does touch directly upon such outcomes, conducted among the still-egalitarian Aché foragers in South America. Their recent adaptation includes being attached to a mission and practicing some horticulture, but the Aché do continue to engage in a substantial amount of foraging. The collaborative study in question focuses on the effects of having generous reputations, which fits perfectly with both Alexander’s indirect reciprocity hypothesis and with our interest here in empathetic giving. Actually, Alexander’s theory isn’t mentioned—possibly because the Aché anthropologists preferred to work with simpler models like kin selection, reciprocal altruism, and costly signaling. But the data presented do provide a nice test of selection-by-reputation theory, and the findings are positive.

This sophisticated study begins by focusing on two variables. One is how productive people are at subsistence, and the other is how freely they normally share their food. The object is to study how extensively others in their band will support them with food when certain hazards that are typical of a tropical forager lifestyle afflict them temporarily. These include short illnesses, bites from insects or snakes, personal injuries, and accidents, any of which can seriously affect an individual’s subsistence efficiency. The odds of experiencing such afflictions are high enough that problems like these are a predictable part of Aché life.

Here’s the scientific hypothesis, which I quote in full because it’s so important to the theory being advanced in this book: “We propose that when temporary disability strikes individuals under conditions of no food storage, able-bodied individuals are more likely to provide food and support to those who have strong reputations for being generous and to high producers.”2

This thoughtful investigation was based on four formalized “types”:

1.Philanthropists, who not only are unusually generous, but are unusually productive so that overall their beneficence is extensive.

2.Well-Meaners, who are exceptionally generous but also are unusually unproductive, so that what they can give away is very limited in spite of their obviously prosocial intentions.

3.Greedy Individuals, who produce a lot but give away relatively little because they are stingy.

4.Ne’er-Do-Wells, who produce little and also are stingy.3

A sample of Aché were carefully interviewed about episodes when they were incapacitated, while their everyday sharing behavior was assessed by direct observation. As a result, it was possible to quantify how productive they were, how much food they normally gave away, and how much help they had received while unable to feed themselves adequately.

The findings show that a generous reputation definitely pays off. Unsurprisingly, the bountifully generous Philanthropists were helped the most in times of need, but interestingly the attitudinally very generous Well-Meaners came in second, even though they had so little to give away. Next came the stingy Ne’er-Do-Wells, who at least had a reason for being stingy, and last were the Greedy Individuals, who were both very stingy and also very well-off. These facts fit well with Alexander’s hypothesis that people prefer to interact cooperatively with individuals with generous reputations and not with those who are known to be stingy. The findings also suggest that being sympathetically appreciative of the needs of others counts socially.

The periods of disability under study were short term. However, because food is not stored, the immediacy of Aché food procurement is such that donations by others can be important to the reproductive success of those who are disabled for even a few days.4 Thus, all four categories of people were in need of help soon after they were incapacitated. In this context, the fitness advantages of the two empathetic types—the highly productive Philanthropists and the much less productive Well-Meaners—significantly surpassed the two selfish types in the number of sympathetic helpers who came to their aid and the amount of help given.

This interesting study shows that both the resources and the motivations involved in being generous or selfish are taken into account indigenously when contingent, “safety net” assistance is needed—and that this important temporary type of help can be given amply or in far less abundance, depending on the reputation of the person who needs assistance. Consider the fact that, even though Greedy Individuals actually give away more food to others than the much less efficient but sympathetic Well-Meaners do on an everyday basis, the latter receive more help when incapacitated. This “generosity is rewarded for its own sake” hypothesis contrasts with costly signaling or “showoff” hypotheses,5 which basically predict that the best hunters will gain the best mating opportunities, but do not include generosity, per se, as a variable relevant to reproductive success.

The Aché pattern is instructive, for it shows that being generous can pay off in times of distress in part because of what is given to others, in terms of quantity,6 but also in part because the emergency help is enhanced if people recognize that previous everyday assistance given to others involved giving when it hurt. This suggests that significant generosity resulting from an ability to appreciate and respond to the needs of others could have been at work in human evolution, in the context of reputational selection.

Ethnographic common sense tells us that LPA peoples’ choices of spouses, work partners, trading partners, and band members worthy of being given extra help will be guided by the society’s general values—which pointedly uphold generosity and strongly condemn stinginess. Unfortunately, to test this working hypothesis, there’s no other formal study comparable to this well-focused investigation with the Aché, who do not fully qualify for the “LPA” category.

Earlier, in exploring this problem, my first move was to go to Robert Kelly’s The Foraging Spectrum, the most comprehensive compendium on hunter-gatherer socioecological behavior put together so far. Kelly acknowledges the hazards of being a forager, but there’s no specific and quantitative analysis of safety net benefits to parallel what we just reviewed with the Aché. What he does say is that “the failure to share among many hunter-gatherers in fact, results in ill feeling partly because one party fails to obtain food or gifts, but also because the failure to share sends a strong symbolic message to those left out of the division.”7

The Aché study bears this out, for the people receiving the least help in their hour of need were the Greedy Individuals, who normally had plenty but chose to share very moderately. The Aché study’s findings can also be phrased positively and with a psychological nuance. Sympathetic generosity, especially sympathetic generosity that is more costly, brings the best benefits from prosocially oriented peers. But even though Kelly acknowledges that feelings of generosity are recognized and important, basically he sees sharing patterns as ensuing from a web of obligations that leads to both requests and demands for food. This certainly is true. But what the Aché study tells us in addition is that there is a sliding scale involved and that psychologically apparent displays of generosity or stinginess are taken into account in a substantial way that can involve both positive and negative selection by reputation.

I believe this finding should hold for any LPA forager group, for the Aché continue to share basic traditional values, which favor both sharing in general and sharing with those in special need. The same golden rule thinking that inspires some individuals to be far more generous than others also influences how band members perceive these individuals, and this is part of how reputations are built.

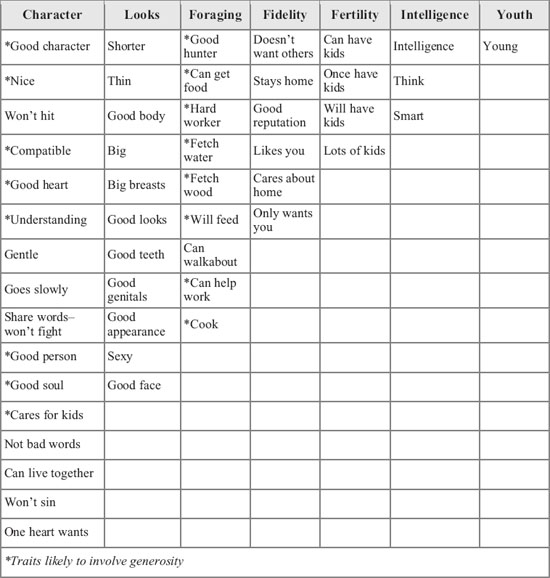

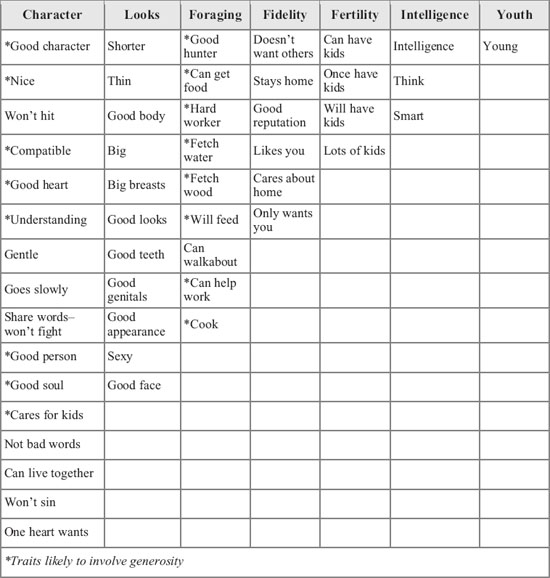

Alexander emphasizes that selection by reputation could work in supporting altruism through partnering in marriage, the assumption being that generous individuals would be given preference. Anthropologist Frank Marlowe queried eighty-five Hadza, who do qualify as LPA foragers, as to the features they wanted in a spouse, and he used an open-ended approach that allowed the Hadza to answer in their own terms.8 As someone who had been working with the Hadza for decades, he then grouped the responses into categories that made ethnographic sense to him.

TABLE VI THE TRAITS MENTIONED BY HADZA

AS IMPORTANT IN A POTENTIAL SPOUSE†

†This table was adapted from Marlowe 2004.

Hadza marriages are not formally arranged by parents, though their blessing is sought, so the principals have substantial leeway in making their choices. Table VI shows the responses as Marlowe “clustered” them, and I have asterisked responses that are likely to imply generosity as a general personal quality that the Hadza value.9

Here I reproduce Marlowe’s findings, in which he has organized all the valid responses for choosing a mate into eight categories. The greatest number of informants referred to the Character (sixteen mentions) of a desired spouse; Looks (eleven), Foraging skills (nine), and Fidelity (six) were also salient. Under Character, nepotistic generosity was obvious in the response “Cares for kids,” whereas by implication altruistic generosity seems possible in “Good character, Nice, Compatible, Good heart, Understanding, Good person, and Good soul.” Under Foraging, generosity is strongly implied in all of the starred categories, which have to do with the subsistence contributions of a marital partner. Furthermore, under Fidelity generosity might have been figuring in the “Good reputation” category even though sexual reputations appear to be the focus.

The virtue of using open-ended responses is that the ethnographer doesn’t impose alien categories that distort the data; the liability is that things that are very obvious to natives may go unstated. I suspect that had Marlowe given his informants a range of choices that included being generous, this would have been a frequent preference because in every hunter-gatherer ethos this is such a major virtue.10 As it is, however, this piece of research goes far beyond most ethnographies in at least providing some major hints as to how a reputation for generosity could figure strongly in one important type of social choice.

Another African example comes from Marjorie Shostak, in a passage that characterizes how the !Kung evaluate prospective marriage partners for their daughters: “In choosing a son-in-law, parents consider age (the man should not be too much older than their daughter), marital status (an unmarried man is preferable to one already married and seeking a second wife), hunting ability, and a willingness to accept the responsibilities of family life. A cooperative, generous, and unaggressive nature is looked for, as well.”11

Here, the ethnographic mentioning of generosity is direct, while the criteria subscribed to by the !Kung parents who are looking out for the welfare of their daughters (and themselves) correspond rather well with criteria subscribed to by Hadza of both sexes in seeking partners individually. Although my coded data for LPA foragers do not specify preferences that are salient in choosing whom to associate with in marital or other partnerships, I believe that the preferences shown in these two unrelated African groups are widespread even though many ethnographers have failed to touch upon this subject.

Making a really definitive case for selection by reputation as a major support for our human capacity for empathetic altruism will require substantial further research effort, and I would place replication of the Aché study high on any list of priorities. Unfortunately, in 2012 there are very few LPA hunter-gatherers left like the Hadza, many of whom are still actually in business as economically independent foragers.

What this preliminary analysis suggests is that ultimately there is far more to explaining hunter-gatherer sharing than a combination of selfishly tit-for-tat reciprocal altruism, resented-but-tolerated theft of meat, costly signaling by the very best hunters, or group selection effects. These models obviously are useful, but some of them seem to reduce sharing and helping behavior to pure economic self-interest, which is ethnographically counterintuitive. To fully understand human sharing and its evolution, the roles that culturally defined generosity and social reputations based on sympathetic generosity play must be brought more directly into the equation.

Meanwhile, we may start with what we know about ourselves as culturally modern humans, who, to reiterate an important and revealing pattern, often respond to televised pleas for help for needy children on the other side of the world and do this anonymously so that the motives can only be ones of generosity. We may also think about both Thomas the Cree hunter and the small Hadza party, none of whom could conceive of not sharing with a person in serious need—even when the generosity was extremely unlikely to be repaid even on a contingent basis, because the recipient was a member of a different group. These examples may be “anecdotal,” but in the absence of systematic information, anecdotes can provide useful leads.

In an important sense, with the Aché it seems to be the thought, or more properly, the feeling, that counts. This is not to say that among hunter-gatherers sharing isn’t guided strongly by a sense of past obligations and past material benefits, or that selfish personal interests are not important in motivating people to engage with a system of indirect reciprocity for the “insurance benefits.” My argument is that generosity based on feelings of sympathy also contributes significantly to the overall process, and that such responses are highly consistent with the deliberately, well-internalized, prosocial values that help such systems to operate as well as they do.

In this light, the Golden Rule is not just about transferring commodities from one person to another so that reciprocation will take place; it’s also about fostering a spirit of generosity that can engender more generosity. And the universality of such preaching can be explained in two ways. One is that people believe in its effects as an agency that can make social relations more positive in an immediate sense. The other is that it more generally functions to oil the machinery of a system of indirect reciprocity so that the system operates more smoothly for everyone and provokes less serious conflict over the long term, which helps groups to flourish. I am not so certain that this second effect is consciously obvious to the actors involved, but hunter-gatherers do actively appreciate social harmony for its own sake.12

What I’m suggesting is that, even though giving to those in need on the basis of a combination of empathy and reciprocity may be difficult to measure scientifically, this is a cornerstone of human cooperation, and it’s definitely not based on precise, tit-for-tat exchange. The unique Netsilik system for seal-sharing may have come rather close in combining an indirect-reciprocity-based system with a very exact structure for contingent reciprocation. But the remarkable network-based system created by the Netsilik appears to be the product of special social and ecological circumstances; their next-door cultural neighbors, the Utku, have no such arrangements.

It’s worth emphasizing here that when the Netsilik cluster for months in aggregations of sixty or more, they do not try to share every seal among the entire population. Rather, they create mininetworks that link about half a dozen hunters in a variance-reduction system on the same scale as in a band of thirty, which also has about the same number of hunters. LPA sharing systems for initial meat distributions can be far less formalized; they depend on everyone’s understanding and accepting the heavily contingent nature of the band-wide system in terms of who produces what—and who gets what. Giving special help to those in temporary need works similarly, but it appears to be influenced quite significantly by generous versus stingy reputations, whereas basically any group member in good standing may receive a fair share of the meat when large game is taken.

The safety-net type of sharing the Aché study investigated definitely was reputation based, and in such cases band life becomes a social stage on which good and bad reputations have been built with respect to being generous—or stingy. The game theory experiments in evolutionary economics that I have alluded to so frequently bear this out quite nicely. Once a prospective partner realizes someone is prone to be generous, a reciprocating, cooperative partnership can develop.

If we take a close look at several dozen geographically distributed foraging societies, as has been done recently in the journal Science,13 and if we focus just on the third of them that fit with our LPA category of hunter-gatherers, there’s a range of band sizes and compositions that varies around some strong central tendencies that are of interest for the theories being developed in this book.

One is a tendency for just a few close kin to be coresident in the same band, which means these bands are far from being kin units. That’s why I’ve said that kin selection models have limited applicability in explaining the band-wide cooperative systems that humans had evolved by the Late Pleistocene, unless the piggybacking “slippage” factor we talked about in Chapter 3 has been very substantial. It also is characteristic of these mobile bands for people to be moving from one band to another, and while this degree of porosity reduces the force of genetic group selection’s operating with much mechanical force,14 nonetheless I think its contributions are likely to be significant.

A further consideration is that as today some form of mostly monogamous marriage would have been universal among earlier LPA foragers. As a two-way process, selection by reputation should have tended to pair off the more generous cooperators for breeding and child-nurturance purposes, as well as for purposes of subsistence. This is strongly implicit in the findings from the Hadza study we considered a few pages back, while with the !Kung it is more explicit. Thus, all of these mechanisms—selection by reputation, reciprocal altruism, kin selection, and genetic group selection—need to be modeled simultaneously. Chapter 3 was devoted largely to studying their workings, and for the most part any of these models can operate quite independently of the others.15

To those models we must add kin selection, for nepotism accounts for the strong generosity that obtains within families. We must also keep in mind George Williams’s thoughts about extrafamilial generosity’s being similar in important ways to generosity that takes place within families. Indeed, in evolutionary terms nepotism may have served as a preadaptation for the evolutionary development of altruism.

The Hadza study hints very strongly at altruism’s being a desirable feature in marital choice, but in any event people in these egalitarian bands pay close attention to whether others are sympathetic, generous with food, hardworking, or trustworthy—versus mean-spirited, stingy, lazy, or overly cunning.16 They often are choosing their associates accordingly,17 and this would apply to band membership, to safety nets within bands, to marriage arrangements, to routine nonmarital subsistence cooperation between families within the band, and to cooperation with people from other bands as a means of establishing long-distance safety nets or trading opportunities.18 Unusual generosity—or a noteworthy lack thereof—can be an important factor in all of these relations.

Having a good, generous character is important, but it’s far from being all important. There are a variety of purely structural constraints in choosing these same types of partners, which will include ongoing kin ties and present or past in-law relationships. But even if an individual is most likely to join a band where close kin or in-laws are living, he or she also is more likely to try to choose the relatives who are more generous or more productive, in line with character traits the Aché and !Kung were favoring, rather than relatives who are unproductive, very stingy, or both. From the standpoint of gene selection, an altruist is more likely to be more successful in cooperation with kin and nonkin alike. And when two altruists choose each other, both will be profiting in fitness terms.

From a theoretical perspective, it has been generosity based in feelings of sympathy for others and their needs that has concerned us here as a rather hard-to-study aspect of hunter-gatherer cooperation. The basis for such generosity can be sustained at the genome level if certain criteria are fulfilled, even though by definition there will be losses of fitness to be accounted for whenever generous behavior fulfills our definition of being altruistic. One criterion is that somehow the altruism must be compensated by the action of at least one of the five mechanisms discussed in Chapter 3. These include two possible piggybacking models, one-shot mutualism and long-term reciprocal altruism models, and the selection-by-reputation model. For several of these models, and also for the group selection model, free-rider suppression also has to be effective.

For LPA foragers, the compensation criterion is being fulfilled, largely, I believe, in the form of reputational benefits. Thus, in combination with free-rider suppression my candidate as a main contributing mechanism to explain the limited but well-exemplified and socially significant altruism of hunter-gatherers has been selection by reputation. There’s a reason for giving these two social selection mechanisms such priority. This lies in the fact that reputation-based social selection is likely to gain special power precisely because the selection process is based on choice. This makes it similar to Darwinian sexual selection, but with respect to its efficacy among hunter-gatherers, selection by reputation might actually be going sexual selection one better.

It would be useful if someone adept at evolutionary mathematics could model all the mechanisms we have discussed in combination, weighting each model for its probable contribution to the maintenance of altruistic genes in human gene pools over the past 45,000 years and more. However, the working hypothesis I’m offering here is that the selection-by-reputation model is likely to be especially powerful because not only is this type of social selection driven by well-focused, consistent preferences, but it also involves a two-way choice process. When the Hadza or the !Kung follow their preferences in choosing partners to mate with, or for that matter just partners to work with, one major effect of their choice behavior will be that generous and fair co-operators will be in a position to successfully choose others who are similarly altruistic and that on both sides fitness will profit.19

If the sympathetic altruists (along with hard workers and trustworthy people) are tending to pair up with others who are similarly socially desirable like themselves,20 this leaves their less desirable counterparts tending to pair up with one another—and suffering the disadvantages of less effective cooperation. Obviously, the advantage goes to the pairs of worthier individuals who are reaping the fruit of superior collaboration—and at the same time are unlikely to suffer from free riding.

This is significantly different from the pattern of having drab peahens who on a one-way basis choose resplendent males whose superior genes bring females more reproductive success. It’s as though both male and female fowl were developing attractive tail feathers to advertise their fitness—and the males were choosing the females with the best tail feathers at the same time that they themselves were being chosen on the same criterion. Were this the case, the power of sexual selection, which is widely acknowledged to be remarkably strong, would be stronger still because both parties would be simultaneously displaying superior fitness—and choosing it.21

When geneticist Ronald Fisher became fascinated with Darwin’s treatment of sexual selection, and with the fact that such choice-driven selection can result in “exaggerated” traits, he thought that costly peacock tail feathers might be explained in terms of “runaway selection,” which results from the escalating interaction of astute female preferences with male signs of genetic superiority.22 When both the traits being chosen and the choosers are involved on both sides of the equation, I believe this could further intensify such effects. Mathematical modeling would be useful in testing this hypothesis, but as a cultural anthropologist obviously that is not my forté.

Richard D. Alexander differentiates between “sexual selection” and “reciprocity selection” (I’ve been using the more descriptive term “selection by reputation” for the latter, for the sake of clarity for a general audience) as he considers this two-way element in the choice behavior that is inherent in selection by reputation:

Sexual selection is a distinctive kind of runaway selection because joint production of offspring by the interacting pair causes the process to accelerate. . . . The defining feature of runaway selection is not acceleration, however, but the tendency of the process to go . . . much further beyond adaptiveness . . . than is ordinarily the case in the myriad compromises among the conflicting adaptive traits that create and maintain the unified organism.

This aspect of runaway selection may hold for reciprocity selection, in which, unlike in sexual selection, both parties can carry tendencies not only to choose extremes but also to display extremes. In social selection . . . an individual can play both roles, of chooser and chosen.23

Of course, one thing that Alexander means when he says that traits selected by reciprocity selection can go “significantly beyond adaptiveness” is that costly altruistic traits might be supported by this type of selection, as well as any other traits that appear otherwise to be maladaptive for individuals but are positively involved with reputational choices that are mutual. This may be the best one hypothesis so far to help explain human altruism—but only, I believe, if it is combined with the very effective kind of free-rider suppression I’ve been emphasizing throughout this book.

Trivers was correct when he suggested that moralistically aggressive groups could come down hard on detectable cheaters. However, I’ve suggested that with earlier humans, and still earlier with Ancestral Pan, it was selfish bullies who were taking the main free rides by competitive actions that favored their own genes at the same time that the genes of their less selfish and less powerful victims were being disadvantaged.

In Chapter 4 we saw that in fifty LPA societies these bullies appear to have been executed far more often than thieves or cheaters, or, most likely, than sexual offenders, which means that their selfish aggressions were seriously problematic for their groups—and also that these powerful free riders were paying a steep price in terms of loss of fitness. We also saw that when earlier humans were intent on being egalitarian, physically punitive types of social selection probably would have been acting far more powerfully than today because initially there was no conscience to help restrain the bullies.

Thus, the earlier stages of free-rider suppression were likely to have been harsh indeed, and we may reasonably assume that the more selfishly driven alpha types, those prone to take risks, were bringing severe and quite frequent punishment on themselves until a conscience evolved to aid them in controlling themselves and thereby in avoiding such dire consequences. As bullying (or cheating) free-rider types increasingly became able to restrain themselves from actions that would bring on punishment, they would have suffered fewer and fewer reproductive disadvantages, so with the existence of more effective self-control there’s no reason to believe that their genes should have gone out of business entirely or have even come close to doing so.

Keep in mind that even though LPA bands are so highly egalitarian, this does not mean there’s an absence of competition. Males compete for hunting prowess, and males (and females) compete for mates. Indeed, egalitarianism itself is based on competition between a few stronger individuals and the subordinates who unite to oppose them. Thus, if a person can channel his or her competitive tendencies in directions that are socially acceptable, and at the same time curb their expression when they will make for fitness-reducing punishment, selfishly competitive tendencies can be quite useful to fitness.

Refraining strategically from aggressive behavior is well exemplified by Inuttiaq, for his efficient, self-conscious evolutionary conscience put him intuitively in touch with his personal social dilemma, and it enabled him to strategically inhibit many of his aggressive responses rather than expressing them in ways that would make his fellow Utku seriously apprehensive—and perhaps prone to dire action.

Not all men prone to despotism manage to curb their despotic tendencies so efficiently. In fact, when Scandinavian explorers first contacted one Eskimo group in Greenland, they noted that a very dominant shaman had killed serially and was being treated with great respect by his group.24 They left before the dominator was killed, so that was not witnessed, but we may be quite confident that somehow he was disposed of. We’ve vicariously witnessed a similar !Kung execution in the Kalahari, and other Inuit groups do away with such men.

In Chapter 7 Table IV showed us that such executions are quite widespread. But whether would-be despots successfully inhibit themselves or not, their actual potency as free riders who can take serious long-term advantage of altruists and others is very limited. Either like Inuttiaq they’re afraid to take the free ride, or like /Twi the aggressive !Kung Bushman they’ll be killed for taking their aggressive free ride too actively.

This leads to an important theoretical point that requires some further emphasis. George Williams’s mathematical portrayal of free riders and altruists assumed that free riders were designed (by evolutionary process) to exploit altruists and thereby disadvantage their genes.25 As a result, altruistic genes could never reach fixation in the gene pool concerned. And if new altruistic genes were to appear as mutants, free-rider mutants would soon appear to drive them out of business.

When we bring in the conscience as a highly sophisticated means of channeling behavioral tendencies so that they are expressed efficiently in terms of fitness, this scenario changes radically. Over time, human individuals with strong free-riding tendencies—but who exercised really efficient self-control—would not have lost fitness because these predatory tendencies were so well inhibited. And if they expressed their aggression in socially acceptable ways, this in fact would have aided their fitness.

That’s why I believe that both free-riding genes and altruistic genes could have remained well represented and coexisting in the same gene pool. Genes that made for bullying free riding could have been useful because they were providing a useful competitive drive, whereas genes that made for altruism could have been useful because altruism was being compensated by reputational benefits and by other compensatory mechanisms we have discussed.

This useful self-inhibition wasn’t perfect. In today’s bands, we still have the occasional active bullies and cheats, who are prone to take major free rides because their own reckless optimism about what they can get away with leads them astray,26 because their dominance or deception is compulsive, or because the feedback their consciences provide them with is faulty. We’ve also seen that it was bullying that caused more of the social problems, and that it did so more frequently. Let’s reconsider the numbers. In Chapter 4, Table I, bullying (“Intimidation of group”) dominated the reported executions, and in Chapter 7, Table III, the most frequently reported acts of deviant social predation were acts of domination by intimidators (with 461 cites for the ten societies), whereas acts of cheating were mentioned only 42 times and for only half of the ten societies sampled even though the central tendency was quite noteworthy. Thus, even though cheating free riders have been academically center stage ever since Trivers made them so famous in 1971, for humans it appears that the major free rides have been taken by politically forceful selfish dominators, whose victims include not only generous altruists who equal them in power but are much less selfish, but also anyone else who is less inclined or less able to dominate others.

Aggressively selfish behavior continues to be a widespread problem today among LPA foragers, and it’s obvious that individually variable, selfishly aggressive tendencies are still with us. If the people so endowed were free to express these propensities without social inhibition, then fair-minded, generosity-driven systems of indirect reciprocity simply would not work. With respect to human cooperation, it’s fortunate that these selfishly aggressive propensities have been susceptible to a remarkable degree of control from within and also from without. From within the human psyche an evolutionary conscience provided the needed self-restraint, while externally it was group sanctioning that largely took care of the dominators and cheaters who couldn’t or would’t control themselves.

At this point I’d like to set forth a historical sequence, starting at the ancestral beginning, as a way of summarizing much of what has been said in the preceding pages—and as a way of keeping my promise to make the natural history of moral origins more historical. To start with, most likely primitive “altruism quotients” in Ancestral Pan were as modest as they seem to be in today’s bonobos and chimpanzees. However, in comparing their degree of innate sympathetic altruism with ours, we must keep in mind that in groups these apes have no way to amplify their cooperation through golden rules.

Our behavioral reconstruction also tells us that a noteworthy if rudimentary potential for (nonmoralistic) group social control existed in this ancestor, a potential that was being directed exclusively at bullies as a resented and readily identifiable type of selfish, competitive, exploitative free rider. This means that the selfish behaviors of certain aggressive individuals could be curbed, even though basically ancestral social orders remained quite hierarchical. This ancestor did have a significant capacity for self-recognition, but in the absence of an evolutionary conscience, its self-control was based just in fear of retaliation, and a capacity for submission.

We cannot be sure how abruptly the next phase of moral evolution began, but it could have involved the escalation of similarly anti-hierarchical social control to a point that rather than profiting, stronger individuals more often were paying a significant price for their attempts at opportunistic, free-riding domination. This could have led to genetic selection in favor of an enhanced capacity for self-control that involved something new: although fear of retaliation by subordinate coalitions continued to slow these bullies down, as a protoconscience developed my hypothesis is that rules could now be internalized as well and that this led to a more sensitive adjustment of individual behavior to group preferences.

It’s impossible to estimate when the capacity to identify emotionally with rules began to seriously affect overall patterns of social behavior and, hence, selection outcomes. Homo erectus with its relatively large brain is at least conceivable as a possibility. However, the position I’ve taken is that such social selection had to become quite decisive starting a quarter of a million years ago, when a still larger-brained archaic Homo sapiens—toward the end of its career—began to hunt large, hooved mammals and depend on their meat. For groups of people in bands to have been really efficient at this, it’s very likely that meat-sharing had to have been well equalized, and this efficiency could have been crucial for group or regional survival when climate change made local environments challenging. As we’ve seen, another possible effect of decisive sanctioning would have been that disempowered alphas would have had problems in reproductively controlling a band’s females. This may well have opened the way for monogamous pair bonding to develop, or to develop further.

I’ve taken 250,000 BP as the magic number for the likely beginning of really strong conscience evolution, but new facts could make for an adjustment of this hypothesis. If it were discovered that some archaics were depending on intensive hunting 400,000 years ago, then that might be our date instead of 250,000 BP. The same would be true if some new Homo erectus site showed systematic hunting of large ungulates a million years ago, although the brains involved would have been much smaller. However, these hypotheses would be difficult to reconcile with the fact that archaic Homo sapiens went from multiple butchers to a single butcher between 400,000 BP and 200,000 BP.

None of this chronology can be definite, but my sequential theory is that the first stage of moral evolution resulted in an evolutionary conscience, and once we became moral, two new patterns were able to develop. One was selection by reputation that favored altruists, and the other was a moralized version of free-rider suppression, which would have targeted not only bullies, but also thieves and cheaters. At that point, we may hypothesize that altruists were beginning to pair up assortatively with other altruists. And with the help of an evolving conscience, more sophisticated strategies of social control would have enabled people to reform those deviants who were more responsive to group rules and to group wishes, rather than injuring or killing them or banishing them.

Unless new evidence is found, by the time people became culturally modern our moral life was basically complete, as LPA hunter-gatherers know it today and for that matter as we ourselves know it today. We had both a sense of virtue and a sense of shameful culpritude, and we understood the importance of human generosity well enough to promulgate our predictable golden rules across the face of a then thinly populated planet. We were a people who in important ways had conquered our own abundant selfishness—even though that conquest required constant vigilance, and considerable active tweaking of the types we have spoken of.