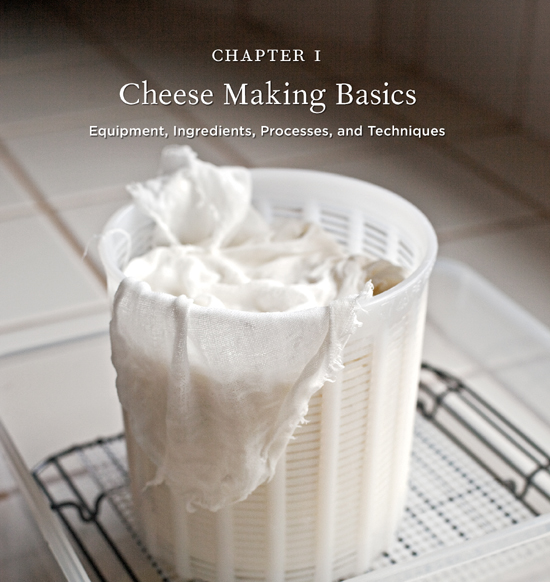

Curds draining on rack prior to applying designated pressure (see Halloumi)

Though there are more than two thousand varieties of cheese hailing from ethnic cultures around the world, on the most basic level cheeses all rely on the same components: milk, starters (whether naturally occurring bacteria or starter cultures), coagulants (such as rennet), and salt.

The process always begins with milk. Then either natural bacteria start to work on the milk, or a starter culture is added. These act on the milk sugar (lactose), converting it to lactic acid. A coagulant is then added to this hospitable environment, causing the milk protein casein to curdle, or coagulate, forming a solid mass of curds. From there, the curds are cut into a specific size, depending on the style of cheese being made. Then they are stirred, drained, and salted; molded or pressed; and, finally, ripened or aged. Voilà: cheese, in all its variety.

In my beginning cheese making class, we start with simple fresh cheeses as the first step in demystifying how cheese happens. Queso blanco, for example, is a very simple cheese made with whole cow’s milk and coagulated with vinegar. The milk is heated to a specific temperature, then the acid (vinegar) is added and stirred to distribute. Like magic, curds begin to appear from the depths of the white liquid. Suddenly, with only a little stirring, there are fluffy curds floating in clear, yellowish whey. Drain the curds and toss them with salt, and you’ve got cheese. Queso blanco is not complex in terms of flavor, but its simplicity demonstrates the fundamental action that takes place in transforming milk into cheese. Not all cheeses are formed as easily, but by following the steps and stages presented in this book, you’ll gain a rounded understanding of how cheeses of varying degrees of complexity stem from this common foundation.

This book is structured to let you develop your skills progressively. We’ll start with the easiest fresh cheeses and add complexity from there. If you are a beginner, I encourage you to start at the beginning and build your skills as you go, because the key to successful cheese making is to start with small, manageable steps. With each success, you’ll want to make more cheese. As you develop your skills and gain an understanding of and level of comfort with the cheese making process, you will build your repertoire on a solid foundation. Be patient. You may be successful the first time you make a cheese, but then again, you may not be. It takes time to master the skills; however, even mistakes can be delicious!

Here are some practices and habits of mind that will help you succeed, whatever your level of cheese making experience.

1. Make Small Batches

Regardless of which cheese you are attempting, make an amount that you have the equipment to handle and the room to ripen, and that you can store and consume within a couple of weeks of its readiness. By making small batches, you have the opportunity to make and taste a variety of cheeses rather than a larger amount of only one. The cheese making recipes presented in this book are geared for small batches, using mostly 1 or 2 gallons of milk. As a general rule, 1 gallon of milk yields 1 pound of firm or hard cheese and up to 2 pounds of fresh cheese. Note that all the yields for the cheeses are approximate.

As I worked on this book, I often had a dozen different cheeses ripening in my cheese refrigerator “cave” at any given time. I worked in small batches, and because the cheeses were aged for different amounts of time, at least one of them was always ready to taste and enjoy. This may be too complicated an undertaking for beginners, but for me it was a perfect arrangement.

2. Set Your Expectations

Before you jump in to make any given cheese for the first time, familiarize yourself with what that cheese looks like and, better still, what it smells and tastes like. It’s important to have a frame of reference for the cheese you are trying to create before you make it, and with such a wealth of information available, both from reference works like this one and from your own senses as you taste and smell a sample, there’s no need to work in the dark. Taking a photograph of the sample cheese before you taste it will guide your endeavors.

3. Plan and Prepare

Wouldn’t you love to make cheese once a week or twice a month and have that to share with family or friends? Once you become proficient, you can make not just one but two or three cheeses in the same session, especially if they are cheeses of the same style. That’s an efficient use of your time, and it allows you to make enough cheese for your own use and some to age or share. Here are some basic steps to help you manage the project and be successful, whether you are making one cheese or several:

• Plan ahead. Some cheeses can be ready in an hour, while some need a 6-month lead time and lots of attention. Determine a realistic scope of work.

• Have your work space, equipment, and tools prepped and sanitary before you begin.

• Keep a notebook to record your thoughts and observations. This is a great catchment system for valuable information that you can apply to subsequent cheese making sessions or use in problem solving. Detailed checklists, worksheets, guides, and observation forms are available for download on this book’s companion website at www.artisancheesemakingathome.com.

When using your kitchen to make any food, but perhaps especially cheese, it is imperative to ensure your space is safe to work in (no clutter or pets around) and is sanitary. While bacteria is part of cheese making, it needs to be the right kind! Don’t try to cook anything else while making cheese. This can lead to cross contamination and also distract your attention from the cheese.

Before you begin:

• Sanitize your work station with a commercial cleaner or a bleach-water sanitizing solution of 2 tablespoons household bleach dissolved in 1 gallon of water.

• Keep a roll of paper towels within reach and a small trash receptacle next to it.

• Sanitize your cheese making pots, equipment, and utensils before and after using. To sanitize properly, wash with hot soapy water, rinse with water, then rinse again with 2 tablespoons household bleach dissolved in 1 gallon of water. Allow to air-dry on a rack set on a sheet pan rather than in your dish drainer to minimize contact with bacteria.

• Consider using dedicated plastic buckets as your sanitary curd-draining “sinks.”

• Keep two clean cotton kitchen towels handy, one for laying out your working tools on and one for drying your hands.

• Do not wear any fragrance while making cheese, as it masks your ability to use your sense of smell to guide the process.

• Wash your hands thoroughly before starting and after handling any nonsterile items.

When you’re getting started, you can take much of your basic equipment from your existing kitchen arsenal of pots, colanders, measuring cups, measuring spoons, whisks, rubber spatulas, ladles, and slotted spoons. Once you are totally immersed in making cheese in your own kitchen, you may want to put pots aside that are dedicated to this function. Think of cheese making in the same way you would canning. Equipment set aside for that purpose is always easier to keep stored, clean, and collected.

Improvising Cheese Draining and Shaping Equipment

Be inventive and recycle other food containers to drain and shape your curds. Some produce containers already have drain holes or slots and function quite nicely for draining curds. Prepared foods sometimes come in containers with interesting shapes. The shape of cut-off flat-bottomed plastic milk containers works for some cheeses (use them in place of square molds of about the same size). These you’ll need to punch with drain holes, but it’s worth the (mimimal) effort.

Before making any cheese in the book, first read the recipe carefully and collect and sanitize all needed equipment. I have noted in the body of each formula which specialty equipment is needed, but will count on your having the following foundational supplies in your kitchen. If you are using specialty equipment or dedicated utensils and make cheese often, store them in a lidded box to protect them from dust and keep them ready for your next session.

Both cheesecloth and butter muslin are necessary supplies in cheese making. Butter muslin has a tighter weave than cheesecloth and is my choice when draining curds, especially small ones, since the goal is to capture as many curds as possible in that cloth. Cheesecloth works well for lining cheese molds, bandaging cheese, and covering air-drying cheeses and can be made into sacks for smoking cheese. Think about the properties of the cloth (open or tighter weave) and apply those in choosing the better cloth for the task at hand.

You can reuse cheesecloth and butter muslin. In fact, once-used pieces are even better than new ones, because the weave will become tighter once the cloth is used or washed, so the cloth will be able to capture curds more efficiently.

To care for your used cloth, first rinse out any curd residue in clear water. Then wash by hand in warm soapy water and rinse thoroughly in water to remove any detergent. As a final step, rinse in a sterilizing solution to remove any residue. To make the solution, in a glass jug or food-grade plastic container with a lid, mix 2 tablespoons each of household bleach and distilled vinegar into 1 gallon of cool tap water. Pour whatever amount you are going to use into a stainless steel or glass bowl and rinse the cloth. Air-dry the cloth, then fold and store it in a resealable plastic bag. Storing cheesecloth in one bag and butter muslin in another keeps things simple. It is also a good idea to keep the cloths batched by milk type and style of cheese they were used on.

The basic equipment and supplies you’ll need for nearly all the cheeses in this book include:

• Butter muslin (4 to 6 yards) and cheesecloth (4 to 6 yards)

• Colander or strainer (made of plastic or another nonreactive material) for draining curds

• Curd cutting knife or 10-inch cake decorating spatula

• Cutting boards or cheese boards: food-grade boards to fit draining trays

• Disposable vinyl or food-service gloves

• Draining bowl or bucket: a large, nonreactive, food-grade vessel for catching up to 2 gallons of whey

• Cheese mats (plastic): to drain molded curds

• Draining rack: nonreactive material, to sit inside draining tray

• Draining trays: food-grade plastic trays or rimmed quarter-sheet or half-sheet baking pans

• Flexible wire stainless steel whisk with a long handle

• Flexible blade rubber spatulas

• Instant-read kitchen or dairy thermometers

• Ladle or skimmer (stainless steel or other nonreactive material) for removing curds from whey

• Paper towels

• Ripening boxes: food-grade storage boxes with lids

• Spoons: large nonreactive metal, wood, or plastic spoons for stirring; one slotted and one not

• Stainless steel pots: a 6-quart pot for working with 1 gallon of milk; a 10-quart pot for working with 2 gallons; a 12-quart pot for making a water bath for indirect heating

• Stainless steel measuring spoons that include the very important ⅛ teaspoon

• Wrapping materials: resealable bags, plastic wrap, and aluminum foil

• Weights: such as foil-wrapped bricks, heavy skillets, or empty milk containers filled with water (see Pressing Cheese)

For a number of the formulas, you will also need the following:

• An atomizer or fine spray bottle: used for spraying mold solution on surface-ripened cheeses

• A cheese press (see Pressing Cheese): 2-gallon capacity

• Heat-resistant waterproof gloves of rubber or neoprene: used for handling hot curds for stretched-curd cheeses

• Hygrometer: a tool for measuring relative humidity; very helpful for monitoring the environment in which cheeses ripen

• pH strips or pH meter: used to measure the acidity of curds in some recipes, especially stretched-curd cheeses

• Specialty wrapping materials: cheese paper

Most of the cheese recipes in this book call for particular cheese molds, in which the curds are drained and shaped before aging. Like any cookware, these require a small investment, but with proper care they will last well past your cheese making lifetime. As you begin to make cheese, I recommend you first get a sense of the styles of cheeses you prefer making. You can build your collection of molds as you go, and you can find a more comprehensive list of molds and photos of these molds on this book’s companion website at www.artisancheesemakingathome.com.

For fresh cheeses, you can buy a few reusable (but called disposable) ricotta baskets from cheese making suppliers for only a few dollars. Recycled plastic berry and tomato baskets also work well for some fresh cheeses. Once you are established in and committed to your cheese making, invest in a few shapes of professional molds that can be used for making a number of different cheeses. These molds include a 4-inch-diameter Camembert mold with a follower (a snug-fitting plug or cap inserted into a cheese mold on top of the curds), a 5-inch-diameter tomme mold with a follower, a crottin mold, and a chèvre mold. Purchase two of any of these configurations to be able to make batches larger than 1 gallon or two cheeses at once. Dedicate a lidded plastic tub to house your collection and keep the molds protected from dust.

Other molds used in this book include:

• 8-inch-diameter Brie mold with a follower

• 4-inch-square mold with no bottom

• Saint-Maure or bûche (log) mold with no bottom

• Saint-Marcellin mold with a rounded bottom

• 7-inch-square, 5-inch-high Taleggio mold with no bottom

• 8-inch-diameter tomme mold with a follower

• Truncated pyramid mold with no bottom

Firm and hard cheeses also require a period of controlled pressing to expel whey and compact the curds. For this process, it is preferable to use a dedicated cheese press—one that you purchase or build. However, you can also use weights to improvise a cheese press (see Pressing Cheese).

Many plans and schemes for improvising cheese pressing equipment can be found online, but a specially designed mechanical cheese press is beneficial for creating the highest-quality firm or hard cheeses, because it distributes the pressure evenly and consistently onto the curds. If you make hard cheese regularly, a press will be worth the investment. One of my favorite presses is the Schmidling Cheesypress; other favorite cheese presses are available from the Beverage People, or you can purchase plans for building your own press from New England Cheesemaking Supply (see Resources).

As with all foodstuffs made with a very few ingredients, the quality and characteristics of the ingredients of cheese are very important. In fact, getting the ingredients right not only makes the difference between a good cheese and an unappealing one, but also determines whether crucial cheese making processes work at all.

It all starts, of course, with milk.

Milk possesses a unique protein structure that enables coagulation, which allows for the preservation of milk as a food source in the form of cheese. Understanding the components of milk and how they behave is critical to understanding the process of coagulation. Milk is composed of water; proteins, including caseins; lactose, or milk sugar; and milk fat (also known as butterfat), those lovely taste globules that contribute so much to your cheese’s final flavor. Because milk is the primary ingredient in cheese, choosing high-quality producers and buying as close to the source as possible will help ensure a great final product.

The primary animal milks used for cheese making come from cows, goats, sheep, and water buffalo (although water buffalo’s milk is rather difficult to obtain and is not featured in this book). However, the type of milk used for cheese making does not determine the style of cheese; in fact, all of these varieties of milk are used for all styles of cheese. That said, there are general differences among the milks produced by different animals. Cow’s milk is sweet, creamy, and buttery, with a fat content of 3.25 percent by weight. Goat’s milk has a tangy, citrusy, almost barnyard quality with a slightly higher fat content than cow’s milk. Sheep’s milk is the richest, at 7.4 percent milk fat by weight, appears golden and oily, and has a gamey flavor. The milks always have a fuller flavor when the animals are fed their natural diet.

Nearly all the cheeses in this book call for cow’s milk, goat’s milk, or a combination of the two. Sometimes sheep’s milk is given as an alternative. If you have a reliable local source, give it a try with the needed adjustments, described below.

Milks can be substituted in the formulas, though adjustments to the amount of coagulant (rennet) may be necessary. You may wish to test the formula as written before making any milk substitutions. The textures and yields of the cheeses will differ from one milk to another. Goat’s milk, having smaller fat particles than cow’s or sheep’s milk, will produce smaller and softer curds. Sheep’s milk will produce a higher yield than the other two milks. If you are substituting sheep’s or goat’s milk for cow’s milk, reduce the amount of rennet by 10 to 15 percent. If you are substituting cow’s milk for goat’s milk, increase the amount of rennet by 10 to 15 percent.

Whether you are working with raw or pasteurized milk, find a reputable source for locally produced, high-quality milk. Once you have a source you like for making cheese, stick with it. Always read the labels for processing procedures and sell-by dates, and always buy the freshest milk available and keep it refrigerated at 40°F. Avoid milks or creams that have stabilizers or thickeners added, as these additives can inhibit proper coagulation and curd development.

If you are able to attain raw milk, you can use a hot water bath and an ice bath to safely pasteurize your milk at home.

Put the milk in the top of a stainless steel double boiler or nonreactive pot. Fill the bottom of the double boiler with water or fill a larger pot with a few inches of water and insert the smaller pot into it. Insert a thermometer into the milk and gently heat the milk to 145°F over the course of no less than 30 minutes, cover, then hold that temperature for 30 minutes. Immediately put the pot of milk into an ice bath to chill rapidly. Keep it in the ice bath until the milk temperature registers 40°F to 45°F. This milk will keep for up to 3 weeks in the refrigerator. It is critical that you follow this procedure precisely. If too little heat or too little time is applied, the possible undesirable pathogens in the raw milk may not be totally destroyed, making the milk unsafe to consume. If too much heat is applied or if the milk is held at temperature for too long, the desirable flora and the proteins in the milk needed for cheese making may be destroyed.

Cow’s Milk and Milk Fat

The cow’s milks called for in this book range in fat content from skimmed (nonfat) milk to heavy cream:

• Nonfat or skimmed milk: 0 to 0.5 percent milk fat

• Low-fat milk: 1 percent milk fat

• Reduced-fat milk: 2 percent milk fat

• Whole milk: 3.25 percent milk fat

• Half-and-half: 10.5 to 18 percent milk fat

• Light whipping cream: 30 to 36 percent milk fat

• Heavy cream: 36 to 40 percent milk fat

The way milk is processed can have profound impacts on how well it’s suited to cheese making and on the characteristics of the cheeses you make from it. By familiarizing yourself with milk processing terms and ingredients, you can better understand their effects on the milk and, in turn, on the cheese.

RAW Raw milk is milk that has not been processed at all; as such, it contains all of its natural bacteria and flavorful flora, resulting in cheeses with more complex and layered flavors than those made with standard pasteurized milks. Of benefit in cheese making, raw milk will curdle and separate if left at room temperature, as lactic bacteria in the air will produce a culture. Thus, when you’re using raw milk, the amount of starter culture needed may differ, and the character of raw milk cheese will therefore differ from that made with pasteurized milk that has been inoculated only with laboratory-produced cultures.

If using raw milk, observe a few precautions. Unless you know your animal, pasteurize raw milk to kill any harmful pathogens before consuming (see sidebar); however, it can safely be used to make cheese if the cheese is aged to 60 days or more. Raw milk will keep about a week; note it also will not be available to many cheese makers, as it is illegal for sale in a number of states. Where legal, look for local cow or goat herd shares (see Resources).

PASTEURIZED If you’re not using raw milk, this is the best choice for cheese making. Pasteurized milk will coagulate better than homogenized milk, and will in fact curdle and separate if left at room temperature, as lactic bacteria in the air produce a culture in the milk. Pasteurization destroys dangerous pathogens, including salmonella and E. coli. However, it also destroys, to a degree, vitamins, useful enzymes, beneficial bacteria, texture, and flavor.

HOMOGENIZED This milk has been processed to break up the fat globules and force them into suspension in the liquid. Meant to prohibit the separation of milk and cream, this process changes the molecular structure of the milk and renders it incapable of producing a culture if left out at room temperature. Homogenized milk sours more quickly than nonhomogenized milk.

PASTEURIZED AND HOMOGENIZED Most milk available at retail is in this form. Some calcium chloride and valuable bacteria are destroyed with each of these processes (homogenization and pasteurization) and in cheese making must be replaced with added calcium chloride and bacteria. In the recipes in this book, it is assumed that the milk used is pasteurized or both pasteurized and homogenized; if you are using raw milk, you may omit the calcium chloride called for in the ingredient list.

ULTRA-PASTEURIZED (UP) OR ULTRA-HIGH TEMPERATURE (UHT) These milks are exposed to extreme heat and cold shock processes to denature the milk to the point that it is shelf stable, allowing it to last longer in transport to the market as well as in the dairy case. Unfortunately, this process is used for many organic milks because they are purportedly more fragile to transport and may sell more slowly at retail. Ultra-pasteurized milk and cream do not work at all for setting proper curds in making cheese and are to be avoided. Ultra-pasteurized milk is heat-treated to 191°F for at least 1 second and ultra-high temperature milk has been heat treated to 280°F for 2 seconds. Then both are instantly stored at cold temperatures (40°F) for a prolonged time.

Starter cultures (starters) are specifically chosen bacterial cultures that are added to warmed milk to start the process of cheese making by acidifying the milk, creating the proper environment for the cultures to grow and flavor to develop. This process of acidification is called ripening the milk, and it includes controlling ripening time and temperature to increase acidity. Different strains of bacteria in a given culture contribute specific flavors, textures, and aromas to the final cheese. One culture might help produce holes or “eyes” in one cheese, for example, while another culture would encourage buttery flavors.

There are two basic types of working cultures responsible for converting lactose into lactic acid, with the main difference being the optimum temperature at which they work. Mesophilic cultures have an optimum temperature of 86°F and a working range of 68°F to 102°F, while thermophilic cultures have an optimum temperature of 108°F to 112°F and a working range of 86°F to 122°F. Within these types of cultures, there are different bacterial strains that work at moderate to rapid rates of acid production.

All of these bacteria are currently isolated in pure form by culture-producing labs for sale to cheese makers. Before making a cheese in this book, look at the ingredient list to ascertain which types of starter or secondary cultures are required. In creating the formulas for this book, I chose specific cultures that I trust and that are readily available in small quantities from cheese making supply companies (see the Cultures Chart for cultures used and the Resources section for suppliers). For detailed information on the various starter and secondary cultures used in this book, refer to the more comprehensive cultures chart online at www.artisancheesemakingathome.com. As you gain experience, branch out and try variations on these cultures to produce your own unique results, keeping in mind that it is always advisable to use as little starter culture as is necessary to make a cheese successfully, instead extending the ripening time, just as a baker might use longer fermentation to develop flavor and structure instead of rushing the process with too much yeast. Less is more.

Most frequently used in bloomy-rind and washed- or smeared-rind cheeses, secondary cultures are bacteria, molds, and yeasts that act in the cheese ripening phase. The veins of mold and the distinct flavors of a blue cheese are caused by secondary cultures, as is the fuzzy white rind on a Brie. These cultures are either added directly to the milk, added between layers of curds, or sprayed or rubbed on the surface of the cheese as it ripens. In washed-rind cheeses, the ripening cultures are also rubbed onto the surface of the rind periodically as the cheese ages. Many cheeses utilize a combination of secondary cultures and enzymes. Flavor-enhancing bacteria such as Propionibacterium shermanii are also useful as ripening cultures.

Cultures are classified based on their temperature of growth, flavor, and acid production features. Culture companies put together specific blends depending on the style of cheese being made. Most of the blends are standard and can contain anywhere from two to six different types (strains) of cultures in varying ratios. Below, you will see some cultures listed that contain the same strains of bacteria; however, those cultures are not identical. They each have a different ratio or percentage of strains based on the desired results.

Note these important reference terms regarding cultures: Acidifier: lactic acid producer; Proteolysis: an important process that refers to the breakdown or fermentation of milk proteins; Proteolytic (protein-degrading) enzymes: contribute to development of desirable flavor and texture in virtually all aged cheeses; Diacetyl: a fermentation compound that contributes a desirable buttery aroma to a cheese; Gas production: refers to cultures that produce CO2.

Culture Name: Meso I

Type: Mesophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis

Suppliers: Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply

Notes and uses: Low level acidifier. Cheddars and Jacks.

Culture Name: Meso II

Type: Mesophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply

Notes and uses: Salt sensitive. moderate to high acidifier with no gas or diacetyl production. Brick, Brie, Camembert, Cheddar, Colby, farmer’s cheese, Jack, stretched-curd cheeses, Parmesan, Provolone, Romano, and some blue cheeses.

Culture Name: Meso III

Type: Mesophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis; Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply

Notes and uses: Moderate to high acidifier with no gas or diacetyl production. Creates a clean flavor and very closed texture, and is proteolytic during aging. Edam, Gouda, Havarti.

Culture Name: MA 011

Type: Mesophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis; Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris

Suppliers: Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply, New England Cheesemaking Supply

Notes and uses: Moderate to high acidifier with no gas or diacetyl production. Creates a clean flavor and very closed texture, and is proteolytic during aging. Cheddar, Colby, Monterey Jack, feta, chèvre.

Culture Name: C101

Type: Mesophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis; Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris

Suppliers: New England Cheesemaking Supply

Notes and uses: Premeasured blend used in a variety of hard, moderate temperature cheeses including cheddar, Jack, Stilton, Edam, Gouda, Munster, blue, Colby.

Culture Name: MM 100

Type: Mesophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis; Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris; Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis

Suppliers: Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply, New England Cheesemaking Supply

Notes and uses: Moderate acidifier with some gas production and high diacetyl production. Brie, Camembert, Edam, feta, Gouda, Havarti, and other buttery, open-textured cheeses, including blue cheeses and chèvre.

Culture Name: MA 4001 Farmhouse

Type: Mesophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis; Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris; Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis; Streptococcus thermophilus

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply, New England Cheesemaking Supply

Notes and uses: Moderate acidifier with some gas and diacetyl production; similar to the bacteria balance in raw milk. Creates a slightly open texture. The culture used for most types of cheese. Caerphilly, Brin d’Amour, Roquefort.

Culture Name: Aroma B

Type: Mesophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis; Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris; Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis; Leuconostoc mesenteroides ssp. cremoris

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply

Notes and uses: Moderate acidifier with some gas production and high diacetyl production. Cream cheese, crème fraîche, cottage cheese, cultured butter, fromage blanc, sour cream, Camembert, Havarti, Valençay.

Culture Name: C20G

Type: Mesophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis; Lactococcus lactis ssp. cremoris; Lactococcus lactis ssp. lactis biovar. diacetylactis; Rennet

Suppliers: New England Cheesemaking Supply

Notes and uses: Premeasured blend chèvre starter containing rennet. Used for making chèvre and other fresh goat cheeses.

Culture Name: Thermo B

Type: Thermophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Streptococcus thermophilus; Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. bulgaricus

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply

Notes and uses: More proteolytic than S. thermophilus alone. Italian-style cheeses including mozzarella, Parmesan, Provolone, Romano, and various soft and semisoft cheeses.

Culture Name: Thermo C

Type: Thermophilic starter culture

Active Ingredients: Streptococcus thermophilus; Lactobacillus helveticus

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply

Notes and uses: Used in Italian and farmstead-type cheeses. More proteolytic than S. thermophilus alone. Emmental, Gruyère, Romano, Swiss.

Culture Name: Bulgarian 411 yogurt starter

Type: Nondairy culture

Active Ingredients: Streptococcus thermophilus; Lactobacillus delbrueckii ssp. Bulgaris

Suppliers: The Beverage People

Notes and uses: For making yogurt.

Culture Name: Brevibacterium linens

Type: Secondary culture

Active Ingredients: B. linens

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply, New England Cheesemaking Supply

Notes and uses: High pH is required for growth of this bacteria. Used to create red or orange rinds on smeared-rind or washed-rind cheeses including Muenster.

Culture Name: Geotrichum candidum

Type: Secondary culture

Active Ingredients: G. candidum

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply, New England Cheesemaking Supply

Notes and uses: Rapid-growing mold that prevents unwanted mold growth in moist cheeses, for use in cheeses made with P. candidum or B. linens. Several varieties are available. Geo 13 produces intermediate flavors, Geo 15 is mild, and Geo 17 is very mild.

Culture Name: Penicillium candidum

Type: Secondary culture

Active Ingredients: P. candidum

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply, New England Cheesemaking Supply

Notes and uses: Produces fuzzy, white mold on the surface of bloomy-rind cheeses including Brie, Camembert, Coulommiers, and a variety of French goat cheeses. Various strains are used to produce a range of flavors from mild to very strong. Strains available include ABL, HP6, Niege, SAM3, and VS.

Culture Name: Penicillium roqueforti

Type: Secondary culture

Active Ingredients: P. roqueforti

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply, New England Cheesemaking Supply

Notes and uses: Creates colored veins and surfaces and is a major contributor to flavor in blue cheeses including Gorgonzola, Roquefort, and Stilton. Various strains are used for a range of colors, with variations of gray, green, and blue. Strains available include PA, PJ, PRB18, PRB6, PV Direct, and PS.

Culture Name: Propionic bacteria

Type: Secondary culture

Active Ingredients: P. shermanii

Suppliers: The Beverage People, Dairy Connection, Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply, New England Cheesemaking Supply

Notes and uses: Used for eye formation, aroma, and nutty or buttery flavor production in Swiss-type cheeses.

Culture Name: Choozit CUM

Type: Yeast

Active Ingredients: Candida utilis

Suppliers: Glengarry Cheesemaking and Dairy Supply

Notes and uses: Acid neutralizer. Moderate aroma development. Promotes surface and interior growth.

Whereas starters acidify the milk, coagulants are used to solidify the milk protein (casein) and form the curds. Coagulants work in concert with bacteria, temperature, and time to curdle, or coagulate, ripening milk. The most basic cheeses use coagulants you probably already have in your home, such as lemon juice or vinegar; these coagulants work at high heat, as do citric acid and tartaric acid. Other coagulants—chiefly rennet—work as the milk is kept at a moderate temperature for an extended period of time.

Animal rennet (containing the enzyme rennin, or chymosin) is naturally found in the stomachs of calves, kids, or lambs, with calf rennet used most often. It is generally recognized that calf rennet produces superior aged cheeses, and for many cheese makers it is their rennet of choice. It is the only animal rennet a home cheese maker will need (see the sidebar for vegetarian options), and is available from cheese making suppliers (see Resources).

Rennet comes in liquid or tablet form. Liquid rennet is easier to measure, dissolve, and distribute into the milk than tablets, and the recipes in this book call for it. Half a tablet is equivalent to ¼ teaspoon of regular-strength liquid rennet; to use tablet rennet, crush the tablet and dissolve in the same amount of water called for in the recipe. Liquid rennet often comes in double strength, so read the label to know the ratio of dilution needed. Rennet should always be diluted in nonchlorinated water because chlorine will kill the enzyme and make it ineffective. Liquid rennet will keep for 3 months, refrigerated. Tablets may be stored in the freezer for up to 1 year.

There are a number of coagulation options available to you if you desire to create a cheese where milk is the only ingredient sourced from an animal. Vegetable rennet is extracted from a variety of plants (such as thistles, nettles, fig bark, fig leaves, and safflower seeds) and is almost as powerful as animal rennet (see Resources). It can be used in any cheese.

Microbial or fungal rennets are made from the fermentation of fungi or bacteria, most typically the mold of Rhizomucor miehei. This rennet is often the choice when making a cheese to be labeled “vegetarian.”

Salt is a key ingredient in cheese making, added for a number of reasons. It is a natural antibacterial, preservative, desiccant, and flavor carrier and enhancer. In cheese making it improves the draining of the curds, adding body to them; it controls moisture; it controls undesirable bacteria and nurtures the growth of desirable bacteria; it contributes to surface dehydration and rind formation; it deactivates the cultures and stops the acidification process; it slows the aging process so cheese can be held long enough to develop the desired texture; and it enhances the inherent flavors by affecting the formation of flavor compounds in the cheese.

Coarse noniodized salt is used in cheese making and is almost always introduced into the process after the whey is drained and at the beginning of or during the ripening process, depending on the style of cheese. Cheese salt is available from cheese supply companies; for the recipes in this book you may also use Diamond Crystal brand kosher salt or fine or flake sea salt. Never use iodized salt.

Water is integral to nearly every cheese in this book. It’s used to dissolve coagulants and other additives, like rennet and calcium chloride, and it’s used to make the brine in which many of the cheeses spend some time. It’s also used to wash curds in a number of recipes. Always use cool (50°F to 55°F) nonchlorinated water to dissolve rennet, calcium chloride, or other additives to ensure their effectiveness, as chlorine not only has an undesirable flavor and odor, but will also make a coagulant ineffective. Bottled or filtered water is your best option for all applications other than for rinsing curds. However, if the only water available is chlorinated tap water, boil it first, cool to 50°F to 55°F, then use at the temperature designated in the recipe.

Pasteurization and homogenization change the structure of milk, removing some of the calcium and destabilizing it slightly. When using any milk that is not raw milk to make cheese, add calcium chloride to increase the number of available calcium ions and help firm up the curds. Calcium chloride is added to the milk before the coagulant. Purchase calcium chloride from a cheese making supplier (see Resources) and store it in the refrigerator according to the supplier’s directions, generally up to 12 months.

Lipase is an enzyme found in raw milk; it is often added in powder form to processed cow’s milk to impart a stronger, tangy flavor to the cheese along with a distinctive aroma. It is used in two degrees of potency: Italase (calf enzyme), considered mild, and Capalase (goat enzyme), considered sharp. When used in combination with certain cultures, the resulting cow’s milk cheese mimics the rich flavor of a sheep’s milk cheese. If using, add lipase powder to the milk before adding the rennet. It can be purchased from cheese making suppliers (see Resources) and should be stored in the freezer and used within 12 months.

Also sometimes called activated charcoal, the finely ground powdered ash used in cheese making is a food-grade charcoal available from cheese making suppliers (see Resources). It is mixed with salt and sprinkled or rubbed on the surfaces of some soft cheeses (primarily goat) to encourage desirable mold growth and discourage unwanted bacteria. The ash neutralizes the surface acidity, allows moisture to be drawn out, protects the exterior, firms up the cheese, and allows the interior (paste) to ripen and stay soft.

Because ash is very messy to apply and stains on contact, use disposable gloves and work carefully. Transfer some of the ash powder to a dedicated salt shaker and add the amount of salt called for in the recipe you are using. To apply ash, place the cheese in the bottom of a plastic tub and sprinkle the surface to be coated with the ash and salt, patting with your hands to distribute and adhere the mixture to the surface of the cheese. Clean the ash from the tub using soapy water and repeating as necessary to remove any oily residue.

Annatto is a dark orange natural food coloring product derived from the seeds of the achiote tree. In its liquid form it is added to cheddars and other cheeses to create their orange color and is also used in washes to create a blush on the surface of some cheeses. Liquid annatto can be purchased from cheese making suppliers (see Resources) and should be stored in the refrigerator and used within 12 months. Ground annatto seed and achiote paste can be found in the spice section of many supermarkets, or in Latin American or Caribbean markets.

There’s a world of culinary herbs and spices that can be used to flavor or add color to cheeses. They are best used in their dried form in flavor-added pressed or aged cheeses, but fresh herbs are also wonderful tossed into the curds or rolled on the exterior of fresh cheeses. As with any ingredient, you want to make sure they are free of pesticides, dirt, and other contaminants. If you are unsure of the source, first boil the herbs or spices in nonchlorinated water for 5 minutes, then let drain and cool on paper towels before adding to the curds.

In this section, I’ll walk you through the basic processes and techniques of cheese making—and some more advanced techniques as well. The formulas for individual cheeses will teach variations on these techniques, but the same basic set of processes applies across the spectrum of cheese making, from the simplest fresh cheeses to the fussiest long-aged washed-rind cheeses. These are preparation; ripening milk; coagulation and curd finishing; draining, shaping, and pressing; salting; drying; affinage, or cheese ripening; and storage. These processes can overlap and even swap places in the order of cheese making steps, depending upon the cheese.

Here you will find descriptions of basic processes and specific instructions for the techniques that make up those processes, like cutting curds or controlling the humidity in a cheese ripening box.

In cheese making, preparation has two components. The first involves reading the recipe through carefully and familiarizing yourself with any terms or techniques that aren’t familiar to you. If it’s a cheese you haven’t tried before and you don’t already have an extensive collection of molds and starter cultures, it may involve ordering some equipment and supplies. Think about timing, too: the creation of a cheese requires performing a series of tasks over a period of hours or days, and ripening tasks can require you to focus on the cheese for weeks or months.

The second part of getting ready involves assembling your equipment, ingredients, and supplies and making sure everything is squeaky clean. Cheese making involves manipulating the microbial content of milk, and your chances of getting a successful result will be aided greatly if you eliminate undesirable microbes from the cheese making environment before you start. Sterilize all your equipment before you use it. Wipe everything else, including work surfaces, with bleach solution or a commercial sterilizing spray, then rinse thoroughly with very hot water to wash away any residue of the bleach or other cleansing chemicals. Air-dry everything rather than wiping it with a cloth, and use clean kitchen towels. Always wash your hands well before you touch your equipment or ingredients, or your curds or cheese (or you may like to use disposable food preparation gloves instead).

Whichever pieces of your equipment are solely for cheese making (as opposed to being taken from your usual kitchen equipment) should be sterilized and air-dried before you put them away. If possible, store them all together in one place—a lidded box is perfect—so they’re collected with easy access when you need them next.

Keep good records of each session using the charts and forms available on my website (www.artisancheesemakingathome.com), such as Planning Your Cheese Making Session Checklist and the Cheese Making Form. Set up a binder for collecting these forms.

Keep a notebook or cheese journal to record your thoughts and observations. This is a great system to retain valuable information that you can apply to other sessions or consult to seek out needed answers.

For every recipe in this book, the first step is to prepare the milk for acidification by warming it to a specified temperature. The general range is from 86°F to 92°F, though some cheeses will require a temperature outside of this range. A slow, steady increase in temperature is crucial to proper milk ripening: too much heat too fast can destroy the proteins you are depending upon to build your curds and can create a hostile atmosphere for the microflora you’re trying to foster.

At the beginning of the cheese making process, start with milk that has been removed from refrigeration and left at room temperature (68°F to 72°F) for 1 hour. Place the milk in the pot and slowly raise the temperature to the specified level before adding the culture or acid coagulant.

Always begin with a sterilized, nonreactive stockpot or pan equipped with a dairy thermometer. For many cheeses, the milk is heated directly and slowly over low heat until the desired temperature is reached. Most of the recipes in this book instruct you to heat the milk directly in this manner. A good general rule to follow for slowly heating milk over low, direct heat is to raise the milk temperature 2°F per minute. For example, if the milk is 50°F when added to the pot and the specified temperature to reach before adding the culture or bacteria is 86°F, it should take no less than 18 minutes to reach temperature.

But sometimes it’s desirable to heat the milk indirectly, using a water bath. This slows the ripening time, heats the milk evenly, and prevents the milk from scorching. If your stove burners are not easily kept at a very low heat, you may prefer using this indirect method instead. When heating milk in a water bath, the time needed to reach temperature can be reduced by half because the water bath is 10°F warmer than the milk temperature you need to reach, and the milk pot is warmed from the bath, heating the milk more quickly yet more gently and evenly than over direct heat.

Technique: Making and Using a Hot Water Bath

To make a water bath, nest a 4- to 10-quart stockpot (depending on the quantity of milk you are heating) inside a larger pot and pour water into the larger pot to come as far up the side of the smaller pot as the milk level will be (for example, if you are heating 1 gallon of milk in a 6-quart pot, the water should come two-thirds of the way up the inner pot). Remove the smaller pot and place the larger pot over low heat. When the water reaches a temperature 10°F warmer than you want the milk to be, put the smaller pot back in the water to warm slightly, then pour the milk into the smaller pot and slowly warm to temperature over the period of time specified in the recipe. If the milk is heating too fast, adjust the burner heat, add cool water to lower the water bath temperature, or remove the pot of milk from the water bath.

In different phases of cheese making you will allow the mixture to sit while maintaining the milk at a particular temperature. There are several ways to accomplish this:

• In order to best maintain the temperature of milk or curds, use the water bath method to heat the milk. The residual heat will dissipate more slowly.

• Always cover the pot.

• Use ceramic-coated cast-iron Dutch ovens or stockpots; these hold the heat better and longer than stainless steel pots.

• If using a stainless steel heavy-bottomed pot, also use a cast-iron simmer plate to maintain heat.

• A towel wrapped around the sides of the pot will help hold in the heat.

• If temperatures under 95°F are required, setting the pot under the light of your stove hood should be sufficient to maintain the temperature.

• If you live in a very cool or cold environment, place the pot on a warmed heating pad to maintain the needed temperature.

Time, temperature, and microbial action are the keys to successfully ripening or acidifying the milk in preparation for proper curd formation. For most cheeses, this involves the addition of one or more starter cultures. After the milk has reached its proper ripening temperature, a small quantity of powdered culture is sprinkled over the milk’s surface and allowed to rehydrate for 5 minutes before being incorporated throughout the milk using a whisk in an up-and-down motion from top to bottom of the pot. This technique is a valuable one: using an up-and-down rather than a circular motion draws the additives down into the milk for more even distribution. It also allows the milk to settle in a shorter period of time and contributes to a more even consistency in the developing curds. Note that if a mold such as Penicillium candidum is to be introduced to the curds, it’s usually added at the same time as the starter culture and incorporated along with the culture.

Technique: Whisking in Starter Cultures and Other Additives

After adding any culture or coagulant to the milk, mix well, using a long-handled whisk in an up-and-down motion at least twenty times, or for the time period specified in the recipe. At a minimum, rennet should be stirred in using an up-and-down motion for 30 seconds to fully distribute it throughout the milk.

The ripened milk begins its turn toward becoming recognizable cheese when a coagulant is added and the milk coagulates or curdles, separating into liquid whey and solid curds. Most cheeses use rennet (either animal or vegetable rennet) as a coagulant, while direct-acid cheeses use lemon juice, vinegar, citric acid, tartaric acid, or even buttermilk. All coagulants are incorporated with a whisk using the same up-and-down motion used to stir in starter cultures (see here). If calcium chloride, lipase, or certain flavorings or colorings are to be added to the milk, they’re stirred in before the rennet, using the same technique. Then, usually, the pot is covered and the milk is left at a specific temperature for a specific period of time until the curds and whey have separated from each other and the curds are firm and give what is called a clean break: when cut with a knife, the cut is clean and not soft or mushy, and some clear whey accumulates in the cut. This means the curds are ready to be cut and finished or washed if necessary, and then drained.

Technique: Testing for a Clean Break

Using a sanitized long-blade curd cutting knife (or 10-inch cake decorating spatula, chef’s knife, or bread knife—anything with a blade long enough to reach to the bottom of the pot), make a short test cut at a 45-degree angle and observe the firmness of the curds. If the cut edge is clean and there’s some accumulation of light-colored whey in the cut area, the curds are ready to be cut into their proper size. If the cut edge is soft and the curds are mushy, the curds are not ready. Allow them to sit 15 minutes longer before testing again.

Curds are cut into varying sizes, from slabs down to rice-size pieces, depending upon the style and desired moisture content of the finished cheese. Larger pieces retain more whey, resulting in a moister cheese. Smaller pieces expulse more whey, resulting in a drier cheese.

Technique: Cutting the Curds

To cut the curds into uniform pieces (rather than into the large slices or slabs suitable for some soft cheeses), use a 10-inch cake decorating spatula or curd cutting knife to make vertical cuts of the designated size all the way down through the curds from surface to bottom. Repeat this across the entire mass of curds. Turn the pot 90 degrees and repeat the process to create a checkerboard of square, straight cuts. Then, using the straight cuts as a guide, cut down through the curds at a 45-degree angle, from one side of the pot to the other. Then turn the pot 45 degrees and make angled cuts down through the curd, working in diagonal lines across the squares of the checkerboard. Turn the pot 45 degrees two more times for two more sets of angled cuts. You will now have cut the curds in six directions total: two vertical and four at a 45-degree angle. Your goal is to cut them quickly and with as much uniformity as possible throughout.

Using a rubber spatula, gently stir the curds to check for larger curds below those at the surface. Cut any larger curds into the proper size.

When making some soft-curd cheeses, after the curds form a solid mass in the pot, gently cut ½-inch-thick slices of the curds using a ladle or skimmer and gently place them in a strainer or layer them in a cheese mold as directed.

Cutting curds

Checking for uniform curd size

Stirring the curds to expel whey and prevent matting

After they’re cut, the curds often need to be cooked, or alternately be very, very gently stirred and then be allowed to rest while at a rather higher temperature than they were kept at during coagulation. This process expulses whey from the curds, allowing them to shrink a bit and firm up, and keeps them from matting together. It is important in establishing the texture of the finished cheese. It also affects the acidity of the curds, which in turn impacts the flavor of the finished cheese, which will be bland with too little acid and bitter with too much. So it’s important to carefully follow directions for temperature and timing for this process. At the end of the cooking process, the cut curds have typically sunk in a mass to the bottom of the pot, with the whey floating above them.

Alternatively, the curds may be washed, if that’s necessary to create the cheese they’re destined to become, or they may simply be ready to drain. Washing curds reduces the lactose level of the finished cheese, making it less acidic, with a smooth texture and a mild flavor. (Gouda is an example of a washed curd cheese.) It is usually done by replacing some of the whey with water that’s either warmer or cooler than the whey (the temperature affects the moisture level of the curds and thus the final texture of the cheese) and alternating gentle stirring and resting to firm the curds.

Or the curds may be set; that is, transferred after a cooking period to a lined colander and immersed in ice water to halt development.

When the cooked or washed curds are sitting at the bottom of the pot covered with whey, the excess whey is sometimes ladled out to expose the tops of the curds, which affects the temperature and the acidity of the curds. Any removed whey can be used for another purpose—the most common being as part of the brine used for that given cheese or as the foundation for making Whey Ricotta. Then the curds are very gently transferred to a cloth-lined strainer or colander, or directly into lined or unlined molds or the barrel of a cheese press, to drain. Curds may be drained entirely in molds, or they may be drained first in a colander or draining sack, then transferred to molds for further draining and shaping and, in the case of firm and hard cheeses, pressing.

Draining, molding, and pressing curds are all processes to expulse more whey and knit the curds together in a solid, whole cheese. As such, these processes have a great impact on the final texture and other characteristics of a cheese.

Technique: Draining Curds in a Colander

Place a plastic or mesh strainer over a bowl or plastic bucket large enough to capture the whey. Line the strainer with clean, damp butter muslin or cheesecloth and gently ladle the curds into it. Let the curds drain for the time specified in the recipe. Discard the whey or reserve it for another use.

Gently spooning curds into a strainer

Draining curds in a colander

Technique: Making and Using a Draining Sack

Line a colander with damp butter muslin and gently ladle the curds into it. Tie two opposite corners of the butter muslin into a knot close to the surface of the curds and repeat with the other two corners. Slip a dowel or wooden spoon under the knots to suspend the bag over the whey-catching receptacle, or suspend it over the kitchen sink using kitchen twine tied around the faucet.

Draining curds in a sack

Technique: Draining Curds in a Mold

Line the mold with damp butter muslin and set it on a rack over a baking sheet or other draining tray. Gently ladle the curds into the mold and let drain for the time specified in the recipe. At the specified time, lift the sack of curds from the mold and place on a clean cutting board. Open the sack, gently lift the cheese, flip it over, and return it to the cloth. Redress and return to the mold. Place back on the draining rack and continue to drain as instructed in the recipe.

For some mold-ripened cheses, use this method of draining in a mold: Set a draining rack over a tray or baking sheet, put a cutting board on the rack and a cheese mat on the board, and, finally, place the mold or molds on the board. Ladle the curds into the cheese mold (or molds) and let drain for the time specified in the recipe. Then place a second mat and cutting board over the top of the mold. With one hand holding the board firmly against the mat and mold, lift and gently flip the bottom board and mat with the mold over and place it back on the draining rack. The second board and mat will now be on the bottom, and the original mat and board will be on top. Continue draining as instructed in the recipe.

Placing partially drained curds in a mold

Gently pressing down curds

Covering curds with tails of cloth

Compressing the curds in a press releases moisture, helping create a smooth interior texture (paste) and smooth rind in firm and hard cheeses. A mold or press is lined with cheesecloth and filled with curds. The tails of the cloth are folded over the top of the curds, and a follower—a piece of wood or plastic that fits inside the mold or press and covers the whole surface of the curds—is inserted. The follower distributes the force of the press evenly over the curds, helping the final cheese achieve uniform shape and texture. Whey runs out of the bottom of the mold or press, which typically has a draining tray or other means of catching the whey.

The amount and duration of pressure is determined by the style and size of the cheese and the desired final texture of the cheese. For the purposes of cheese making, pressure is measured in pounds per square inch (psi) of the surface area. This pressure can best be obtained by using a cheese press, which is designed to apply a specified amount of pressure. However, cheese can be successfully pressed at home using any number of simple weights (see below). The formulas in this book specify the amount of weight needed, not the pressure or psi. It is expressed like this: “press with 5 pounds for 15 minutes.” Typically, light pressure or weight is applied at first, and then the pressure is increased as the curds expulse more whey and become firmer and more cohesive.

Partway through the pressing process, the cheese is flipped one or more times. It’s removed from the mold or press, unwrapped from its cloth, turned over, and redressed in the same cheesecloth before being returned to the mold for more pressing. Flipping helps make the cheese uniform in texture and shape. If you encounter a recipe for a firm or hard cheese that has no instruction for how much pressure should be applied, here is a general rule you can follow with success: Apply enough pressure to compress the curds into a smooth surface without squeezing the curds out. Press until the whey stops draining. Or you can lightly press for 1 hour at 8 to 10 pounds, then flip, redress, and apply medium pressure overnight at 20 to 30 pounds of pressure. Then flip, redress, and press for 8 to 12 hours at the same pressure.

There are a number of simple weights for pressing that you can create from your home kitchen. Water-filled milk containers or buckets and other pantry items will work for the home-batch quantities of cheese presented in this book. Be resourceful with what you have available, but consider the size and shape of the weight or container to ensure the weight will stay put. Here are some examples:

LIGHT PRESSURE: 5 TO 10 POUNDS

• A jar (2 cups) of tomato sauce = 15.5 ounces—about 1 pound

• 1-quart plastic milk container filled with water = 2 pounds

• Marble mortar (without the pestle) = about 2½ pounds

• A brick = 4 to 5 pounds

• ½-gallon plastic milk container filled with water = 4 pounds

• 1-gallon plastic milk container filled with water = 8 pounds

MEDIUM PRESSURE: 11 TO 20 POUNDS

• A cement block = 10 to 20 pounds

HEAVY PRESSURE: 21 TO 40+ POUNDS

• 5-gallon bucket filled with water = 40 pounds

Technique: Filling a Cheese Mold or Press for Pressed Curds

Ladle the curds into a mold or press lined with a single layer of damp cheesecloth and use your hands to distribute the curds evenly; pull up on the cheesecloth to eliminate any folds. Smooth out the top tails as best you can to prevent indentations in the surface of the cheese. Excess tails of cloth can be cut off to ensure a smoother surface. Gently press down on the curds with your hand to close up some of the gaps; if left, gaps are not only unattractive but are likely homes for unwanted bacteria and mold; exceptions to this process include both Stilton and Cabra al Vino, where gaps are part of their craggy style. Place the follower on top of the wrapped cheese in the press and press according to the recipe and the press manufacturer’s instructions.

Technique: Flipping Cheese During Pressing

Partway through the pressing period and as specified in the recipe—usually soon after the curds are solid enough to be handled without falling apart—lift the cloth-covered cheese from the mold, unwrap it, turn it over, redress it in the same cloth, and return it to the mold, so that the surface of the cheese formerly on top is on the bottom.

In the process known as cheddaring, warm curds are drained over heated whey to further expel whey from the curds and knit them together to form a slab. The slab is then carefully milled, or cut into uniform pieces or broken into small chunks, without removing any whey. The milled curds are then salted and placed in the mold or press and are flipped at least one time during pressing to create an even shape.

How to Use Whey

Whey may be saved and reused in a number of practical and tasty ways. Because it is acidic, it can sour fairly quickly, so it should be refrigerated within 2 to 3 hours. It can be frozen and used within a couple of months. It makes terrific soup stock, it can be all or some of the liquid for cooking beans or rice, and it is fun to use when making bread. If you raise pigs, feed it to them; they’ll love you forever. Additionally, whey can be fed to acid-loving plants, such as tomatoes.

Salt—usually coarse salt, and always uniodized salt—is a crucial element of cheese making (see section on Salt). There are two basic methods of adding salt to a cheese: dry salting, which can happen before or after pressing, after the curds have been drained; and brining, which typically happens after the curds have been drained and shaped. Dry salting and brining are often used in combination.

In addition to adding flavor to cheese, salt aids in rind development, which is necessary to allow the interior, or paste, to ripen properly. During brining or surface dry salting, salt dissolves into the moisture at the surface of the cheese, and water is drawn to the surface and evaporates, leaving behind a layer of dehydrated cheese, which is the rind. In semisoft, firm, and hard cheeses, the rind acts as a barrier protecting the paste development, and it also influences what can grow on the surface. On surface-ripened cheeses, dry salting promotes the growth of desirable microorganisms needed for ripening, and some of the salt passes into the cheese as well.

The thickness and strength of the rind can be controlled by the brining conditions and the humidity and temperature during and after dry salting. Hard-rind cheeses are kept at a lower humidity (85 to 90 percent) after salting to allow moisture to evaporate more quickly, leaving a layer of rind behind. The application of salt to the exterior of the cheese is repeated until the desired firmness of rind is achieved. Soft- rind cheeses are kept at a high humidity (95 percent) after salting to prevent too much evaporation and rind formation, and to allow desirable bacteria and molds to grow and migrate into the cheese.

Too much salt can inhibit bacteria growth and slow down the ripening process, and too little salt can allow unwanted bacteria to grow. This delicate balance takes time and skill to master. The information here is based on guidelines used by professional cheese makers. However, I often make adjustments to brine strength, the duration of brining, or the amount of salt rub when using other cheese makers’ or my own formulas, using my experience as a guide. After testing a few recipes that call for brining or salting, you may choose to make adjustments as well, based on your own growing body of experience.

Sprinkling salt directly on the cheese, referred to as dry salting, can occur before or after pressing, depending upon the cheese. The curds should be between 87°F and 92°F at the time of salt application; this helps some of the salt penetrate the interior of the curds. If you are tossing curds with salt, divide the salt into two or three batches and gently toss the curds after each addition for uniform salt distribution.

Here are some general rates of dry salting:

• 1 teaspoon per 3- to 4-ounce cheese, sprinkled evenly on top and bottom of the cheese

• 1½ teaspoons per 8- to 10-ounce cheese, sprinkled evenly on top and bottom of the cheese

• 2 teaspoons per 14- to 16-ounce cheese, sprinkled evenly on top and bottom of the cheese

• 1 teaspoon per 1-gallon batch of milk for dry salting cheddar curds

Flavored salts (smoked, herbed, porcini, lavender, green tea, and even chocolate, for example) and various fleur de sel from all over the world can be used to dry salt cheeses with amazing results (see Honey-Rubbed Montasio).

Most firm and hard cheeses are salted using brine, with cheddar as one notable exception. A brine can be flavored with spices, beer, ale, wine, or spirits and can be applied either by soaking certain cheeses or as a wash that is rubbed or brushed onto a cheese’s surface to flavor its exterior and develop its rind. Bacterial brines or surface-ripening solutions of varying formulas listed in the recipes are washed or sprayed on certain surface-ripened cheeses to promote the growth of surface bacteria. Some cheeses, such as feta, are salted and then preserved in brine. For those just starting to make rinded cheeses, you may fear the brining process will create an overly salty finished product. However, at that point the salt has only begun to make its contribution and will dissipate with time; let the salt do its job.

To make brine, dissolve salt thoroughly in cool water, cover, and chill to 50°F to 55°F before using. Keeping the brine at this temperature throughout the brining process aids in uniform salt absorption and optimum rind formation. The cheese should be brought to the same temperature as the brine beforehand, with some exceptions; for example, Gouda and feta are placed in the brine directly after pressing, while still warm. Unripened stretched-curd cheeses like mozzarella may be cold brined (below 50°F) to cool them quickly and help them avoid excessive moisture loss.

Use a nonreactive container and make enough brine to surround the cheese and allow it to float. As a rule of thumb, 3 to 4 quarts of brine will float two 2-pound cheeses and will fit into a container that’s of a manageable size. All cheeses should be turned over at least once during the brining time indicated to ensure even salt intake and evaporation.

Brine can be kept and reused for up to 1 month if filtered of solids. If it exceeds 55°F for any length of time, make a fresh batch to ensure maximum effectiveness.

Simple brine

2 percent salinity: 1½ teaspoons salt to 1 cup water, cooled to 55°F

Used as a wash.

Light brine

10 percent salinity: 13 ounces salt to 1 gallon water

Used to flavor soft or stretched-curd cheeses (like mozzarella or bocconcini) that stay in a lightly salted solution for a short period of a few hours to a few days before consumption.

Medium brine

15 percent salinity: 19 ounces salt to 1 gallon water

Considered a pickling brine used for a salty profile. A cheese such as feta or Halloumi may be stored in this brine after a short time in saturated brine.

Medium-heavy brine

20 percent salinity: 26 ounces salt to 1 gallon water

Used to preserve cheese and add distinct salty flavor.

Near-saturated brine

22 percent salinity: 28 ounces salt to 1 gallon water

Used for firm, hard, and washed-rind cheeses to draw in salt, draw out moisture, and set up rind development.

Saturated brine

25 percent salinity: 32 ounces salt to 1 gallon nearly boiling water; some salt will remain undissolved

Used for firm, hard, and washed-rind cheeses to draw in salt, draw out moisture, and set up rind development; excessive moisture may be lost too quickly at this level if brined for too long a time; some cheese makers prefer to use the 22 percent level.

All cheeses other than fresh cheeses benefit from some degree of air-drying before they enter their ripening stage. In soft cheeses, a degree of drying sets the surface of the cheese, allowing it to hold its shape in preparation for the next stages of ripening. In semisoft, firm, or hard cheeses air-drying is essential in setting the surface of the cheese, preparing it for rind development and aging.

After draining in a mold or brining, place the cheese on a mat or rack set over a baking sheet, loosely cover with cheesecloth, and air-dry at room temperature (68°F to 72°F) until the surface is dry to the touch—usually no less than 6 hours and up to a couple of days—before placing it in its ripening box or cave. A fan can be used to improve air circulation and inhibit mold growth.

Soft-ripened cheeses are dried in a well-ventilated room for 1 to 3 days, ideally at 58°F to 60°F with 85 percent relative humidity (RH). These conditions help ensure the drying process does not happen too quickly, which could cause the surface to crust and inhibit even ripening. With soft cheeses, the way to check for satisfactory dryness is to press the cheese with your finger. If the cheese is resilient and keeps its shape, it is dry enough. At this point the cheese is ready for final ripening.

Ripening the cheese—also called aging or affinage—is the final, and for many cheeses the most critical, step of the cheese making process. It involves holding a cheese for a designated period of time to develop its flavor, texture, and final personality. A controlled combination of temperature, humidity, and air circulation is needed for the proper ripening of any given style of cheese.

For the home-based cheese maker, this important final stage can also be the most challenging. The cheese will indeed ripen, but not always at the pace or with the results anticipated. Ripening can oftentimes be difficult and frustrating to manage and, with some cheese making episodes, result in disappointment. The road to success takes time and practice. This is where the craft of cheese making takes its place alongside the science. Refer to the companion website www.artisancheesemakingathome.com for aging charts by style of cheese.

If the cheese didn’t come out the way you intended, a valuable lesson has been presented. Maybe you really enjoyed the problem cheese. In that case, you’ve discovered a new one. But whether you found the cheese enjoyable or unappealing, you can analyze both the results and the steps you took to arrive at it to help you make adjustments for the next time you attempt that cheese. Be sure to keep good notes of what you did and when and how you did it every step of the way in making the cheese, and refer to the troubleshooting guide to help figure out what may have gone amiss. For a sample cheese making form, refer to www.artisancheesemakingathome.com.

I describe here the general environment and equipment you will need for proper and successful ripening; specific cheese formulas have more precise instruction.

Technique: Controlling Unwanted Growths

Mold and bacteria will grow on your cheeses. During the ripening process the surface will show a bit of fuzz or become slightly slimy from bacteria. Any black fuzz, blue or greenish molds, or yellow-colored growth other than what is described in the development of the surface is undesirable. What do you do? Remove it by rubbing with a small piece of cheesecloth dipped in a vinegar-salt solution (a 1-to-1 solution of distilled vinegar and salt), then wiping clean with a piece of washed, dry cheesecloth. Hand wash and rinse out the cheesecloth, dry, and store in a jar in refrigeration along with your stored washes and brines. Reuse this rag for the same function.

Used to provide the perfect controlled environment for ripening, a ripening box can be as simple as a food-storage vegetable keeper with adjustable vent holes, though there is a dedicated box called the Cheese Saver that works well for small wheels of cheese and for storing cheeses (see Resources).

As a general rule, choose a ripening box that’s more than twice as big as the cheese it will contain to provide for good air circulation and inhibit mold. You will also need a rack or tray on which the ripening mat and cheese can sit for drainage and a piece of moistened natural sponge or paper towel to introduce moisture as a humidity contributor.

Understand that this ripening system has many variables. It is up to you to monitor the progress of the ripening. Being able to properly ascertain by sight, smell, and touch what is going on with the cheese takes practice. Use your senses from the very beginning, and you will learn from each session.

Technique: Using a Ripening Box

Insert the rack or tray into your box. Place a small bowl with a chunk of natural sponge in the box at one end and add just enough water to wet the sponge. This will contribute humidity. Place the cheese on a mat set on top of the rack, then loosely cover the box for the first few days of ripening; this helps keep the humidity in check—you want it just right. Once whey stops draining from the cheese, secure the lid. As the cheese ripens, open the box daily to provide for air exchange and to wipe out any moisture from the inside surfaces of the box. A small bowl of salt placed inside the box can also act as a desiccant. The air should be moist; the cheese should not be. If it is, wipe any excess moisture from the cheese and the box and adjust the lid for more air circulation and to adjust the humidity.

Ripening rooms or caves with controlled conditions are used by professional cheese makers, but a temperature- and humidity-controlled refrigerator or wine cooler works just fine. Even home basements or protected corners of garages can be outfitted to function as ripening “caves.”

To dedicate a home refrigerator to cheese ripening, retrofit it with a hygrometer to help you maintain a given temperature and humidity. You can also adjust humidity more simply by lining a sheet pan with a kitchen towel and filling it with water, then placing it in the fridge. I have found that this method increases the humidity enough to support the needs of cheeses in their individual ripening boxes. I keep track of the temperature and humidity inside my cheese refrigerator with a wireless device that tells temperature and relative humidity.

Note that unless you are ripening cheeses of the same type outside of individual boxes, needing the same temperature and humidity within this regulated space, you will most importantly need to carefully monitor the humidity within each ripening box—that is the more critical environment to manage.

You can also purchase a wine cellar refrigerator. They are manufactured to maintain the cellar temperatures needed for cheese making. Some even come with humidors. These are perfect ripening caves that need no reprogramming or additional attachments. You’ll still need to use ripening boxes if you are aging more than one variety of cheese at the same time. Shop for these wine cellars at your local home improvement store.

In addition to being dry salted or brined, some cheeses are soaked, washed, or rubbed with alcohol or wrapped in spirit-macerated leaves as a means of preservation, as a ripening vehicle, and as a flavor contributor. Armagnac, beer or ale, bourbon or other whiskeys, brandy, Calvados, cider, cognac, eau-de-vie, grappa, vodka, and walnut liqueur are the most widely used spirits, though flavored vodkas and nontraditional spirits can be used as well. See O’Banon, Lemon Vodka Spirited Goat, and Époisses for examples of cheeses washed in spirits or wrapped in spirit-macerated leaves. The sidebar Leaf-Wrapped Cheeses gives instructions for using leaves—macerated or otherwise—to wrap cheeses for ripening.

Stovetop wok-smoking Scamorza

Low-temperature cold smoking (50°F to 60°F) is used for cheeses because the goal is not to cook or melt the cheese; the smoke acts as a flavoring. The smoke evaporates moisture, causing the milk fat in the cheese to rise to the surface. When combined with the smoke, the milk fat forms a thin skin on the surface, which acts as a preservative. The smoke just kisses the exterior of the cheese but does not infuse it and will not impart much if any color to the surface of the cheese.