likelihood if new sexual risk/suspicion about a partner with urethritis arising within 4 weeks (usually).

likelihood if new sexual risk/suspicion about a partner with urethritis arising within 4 weeks (usually).Men with symptoms suggesting urethritis

Vulval irritation/discomfort/pain

Sexual assault: general principles

• Presentation:  likelihood if new sexual risk/suspicion about a partner with urethritis arising within 4 weeks (usually).

likelihood if new sexual risk/suspicion about a partner with urethritis arising within 4 weeks (usually).

• Age: most commonly found in ♂ from late teens to 50 years.

• Symptoms: usually prominent dysuria and/or urethral discharge (may just be found on examination).  urinary frequency and systemic symptoms unusual.

urinary frequency and systemic symptoms unusual.

• Urethral smear: =>5 polymorphonuclear leucocytes (PMNL) per high-power field (HPF) and/or urinary thread from FVU: =>10 PMNL per HPF. Consider sending air-dried smear to lab if on-site microscopy unavailable.

• Urethral swab (NAAT and preferably culture) or FVU (NAAT) for Neisseria gonorrhoeae (urethral culture before treatment for gonorrhoea); FVU or swab using NAAT for Chlamydia trachomatis and Mycoplasma genitalium.

• mid-stream sample of urine (MSSU) to exclude urinary tract infection (UTI), if relevant;

• exposure to other STIs—consider screening, e.g. syphilis and HIV serology.

• Treat on microscopy findings or clinical assessment if microscopy unavailable (while awaiting lab results).

• PN/contact tracing must be arranged. Contacts of gonorrhoea, chlamydia, or mycoplasma should be treated epidemiologically. Treatment may be appropriate for contacts of NSU with negative tests for the above tests, if likely to be sexually acquired.

• Abstain from sex until treatment completed and partner(s) treated.

• Sexual history: long-standing stable sexual relationship/not sexually active

• Age: >50 years (prostatism with UTI more common)

• Symptoms:  frequency, loin pain, pyrexia, malaise

frequency, loin pain, pyrexia, malaise

• urethral smear for Gram stain, specimens for N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, M. genitalium

• offer syphilis and HIV serology.

• FVU and MSSU typically both opaque, failing to clear on acidification (e.g. 5% acetic acid). Dip-stick usually shows leucocytes, nitrites, protein, and blood. Send MSSU for microscopy, culture, and sensitivity.

• If suspected, manage as UTI.

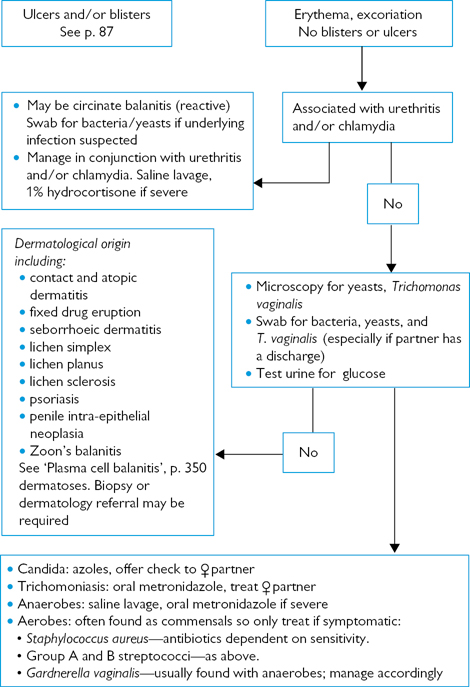

Fig. 6.1 Investigating balanitis and balanoposthitis.

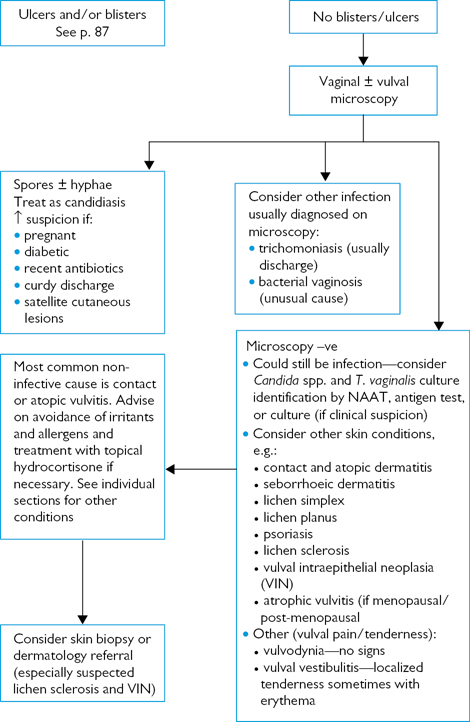

Fig. 6.2 Investigating vulval pain.

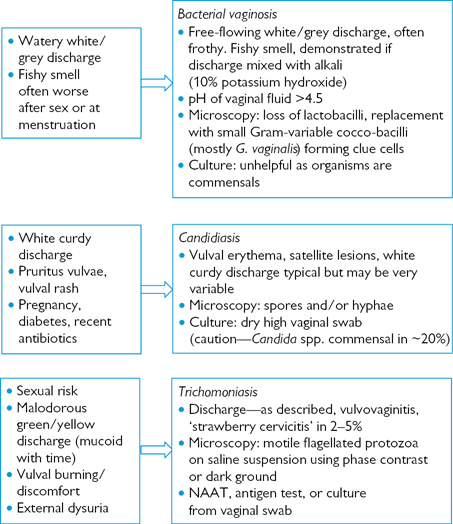

The normal physiological discharge will alter with the time of the menstrual cycle, pregnancy, and sometimes hormonal contraception. Finding lactobacilli without other anomalies provides reassurance pending swab results.

Remember that it is common for infections to coexist.

Fig. 6.3 Altered vaginal discharge—Investigating primary vaginal conditions.

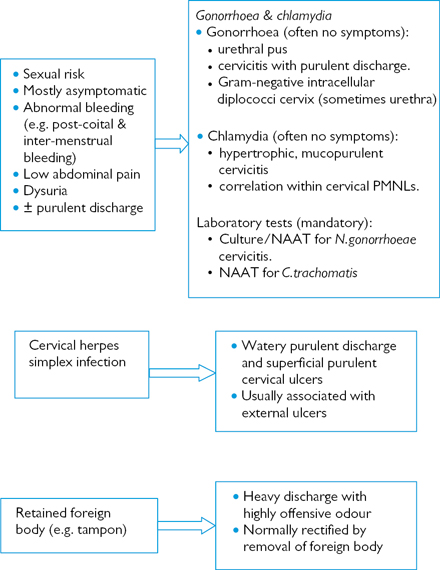

Fig. 6.4 Altered vaginal discharge—Investigating other common GUM presentations.

Fig. 6.5 Investigating and managing anogenital ulceration.

• swab – in viral transport medium

• diagnostic confirmation important, although treatment should commence on clinical grounds

• full STI screen advised. Internal examination in ♀ may be deferred until acute symptoms resolved.

• if clinically suspected, start oral antiviral treatment

• analgesia may be required (e.g. 30–60 mg codeine phosphate 4–6 times a day)

• suggest micturition in warm bathwater if severe dysuria. Supra-pubic catheterization may be required if urinary retention.

• Supportive treatment (e.g. saline bathing) unless unusually severe when oral antiviral treatment is justified

• STI screen only if new risk.

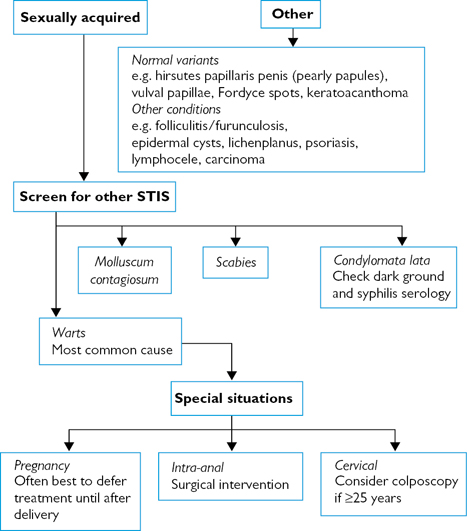

Fig. 6.6 Investigating genital lumps and bumps.

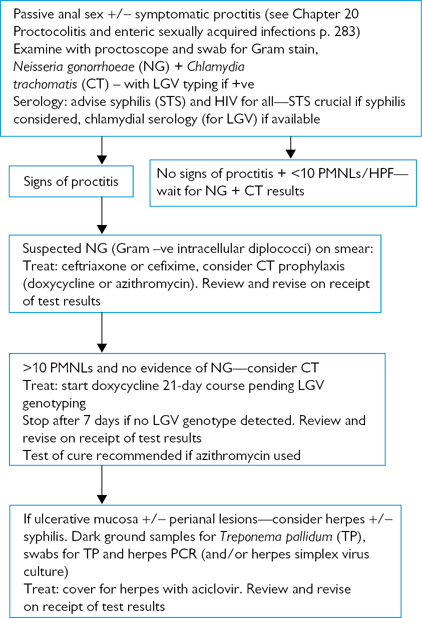

Fig. 6.7 Investigation and management of proctitis.

See Tables 6.1 and 6.2.

Table 6.1 Epidemiological treatment for contacts of STIs

| Infection of index case | Treatment need | Contact treatment |

| ♀ candidiasis ♂ candidiasis | × ✓ | Antimycotic treatment often required |

| Chancroid | ✓ | Ciprofloxacin 500 mg bd for 3 days Ceftriaxone 250 mg single dose, IM |

| Chlamydia | ✓ | Azithromycin 1 g stat., doxycycline (100 mg bd for 7 days (recommended if likely rectal infection), erythromycin 500 mg bd for 14 days |

| Donovanosis | ✓ | Azithromycin: to current contacts and those from 30 days prior to onset of symptoms |

| Epididymitis (if non-gonococcal) | ✓ | Azithromycin, doxycycline, erythromycin (as chlamydia) |

| Gonorrhoea | ✓ | Single doses of cefixime 400 mg; ciprofloxacin 500 mg; amoxicillin 3 g + probenecid 1 g; ceftriaxone 250 mg IM |

| Hepatitis A | ✓ | Hepatitis A vaccine HNIG* – close contacts <2 weeks |

| Hepatitis B | ✓ | Specific hepatitis B immunoglobulin (<7 days). Super-accelerated active immunization |

| HIV | × /✓ | If <72 hours, consider post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) with highly active antiretroviral therapy for 1 month |

| Lymphogranuloma venereum | ✓ | Doxycycline: to current contacts and those from 30 days prior to onset of symptoms |

| Non-gonococcal urethritis | ✓ | Azithromycin, doxycycline, erythromycin (as chlamydia) |

| Mucopurulent cervicitis and PID | ✓ | Azithromycin, doxycycline, erythromycin (as chlamydia). Consider anti-gonorrhoea treatment |

| Mycoplasma genitalium | ✓ | If no macrolide resistance in index patient: azithromycin 500 mg followed by 250 mg daily for 4 days, |

| If macrolide resistance in index patient: Moxifloxacin 400 mg oral daily for 14 days | ||

| Pediculosis | ✓ | Permethrin or malathion to sex contacts |

| Scabies | ✓ | Permethrin or malathion to sex and household contacts |

| Syphilis—early Syphilis—late | × /✓ × | Consider benzathine benzylpenicillin 2.4 MU IM stat or oral doxycycline 100 mg bd for 14 days |

| Trichomoniasis | ✓ | Metronidazole 2 g single dose or 400 mg bd for 7 days |

* Human normal immunoglobulin

Table 6.2 No partner treatment required

| Infection | Need | Contact treatment |

| Bacterial vaginosis | × | Not required |

| Hepatitis C | × | |

| Anogenital herpes | × | |

| Anogenital warts/molluscum contagiosum | × |

NB: Tables 6.1 and 6.2 only provide information about epidemiological treatment. They do not cover the requirement to offer contacts at risk STI screening, information, and advice.

• Oro-anal: anilingus (also spelt analingus).

Lifestyle reports suggest an increase in oral sex, especially among adolescents, and MSM. Factors include a younger age at sexual debut, avoidance of pregnancy, and reducing HIV risk (in MSM). Oral sex is often not regarded as sex, or as relevant to the transmission of infection, so direct questions regarding its practice must be asked when relevant (Box 6.1).

Box 6.1 Receptive oral sex or receiving oral sex

Descriptions of oral sex can be confusing because of variable interpretation:

• Receptive oral sex has been used in the same sense as receptive anal sex, i.e. accepting the sexual partner’s penis into one’s mouth.

• Insertive oral sex has similarly been used to describe the act of inserting one’s penis into the partner’s mouth.

• On the other hand receiving oral sex has been used to describe male or female genital stimulation by the sexual partner’s mouth. Giving or (performing) oral sex is the opposite of ‘receiving’, i.e. stimulating the partner’s genitals by one’s mouth. In view of the greater applicability, the descriptions used in this book are:

• receiving oral sex—indicates genital stimulation by the sexual partner’s mouth (‘insertive oral sex’ in some publications).

• giving oral sex to indicate stimulating the sexual partner’s genitals (‘receptive oral sex’ in some publications).

Idiosyncratic reports of genital lesions arising from trauma, usually from the teeth, but also related to the use of piercings. Underlying medical conditions may aggravate, e.g. vulval haematoma in ♀ with essential thrombocytopenia. Oral injuries arising from fellatio have been reported, with the typical lesion appearing as a circular area on the soft palate consisting of erythema, petechiae, dilated blood vessels, and vesicles. A case of accidental condom inhalation has been reported in a ♀ presenting with a chronic cough, sputum, and fever with a collapse-consolidation of the right upper lobe. Videobronchoscopy revealed the presence of a condom in the right upper lobe bronchus. Case reports have associated vaginal insufflation (blowing into the vagina) with venous air embolism (through the uterine veins or subplacental sinuses) during pregnancy, and pneumoperitoneum (presenting with acute severe abdominal pain) in any ♀, including those who have undergone hysterectomy, independent of operative procedure.

A probable cause of NGU associated with receiving oral sex. Adenovirus infection has also been implicated in cervicitis and genital ulceration, as well as keratoconjunctivitis. Seasonal clustering of cases is reported. Types identified in studies are 4, 8, 9, 35, 37, and 49, and NGU typically presents with marked dysuria, mucoid urethral discharge, and meatitis. Extragenital manifestations include conjunctivitis, pharyngitis, and constitutional symptoms.

There is a lack of clear reproducible evidence of an association with oral sex in general. However, a significant association has been reported with receiving oral sex in lesbians. Mycoplasma hominis, associated with BV, has been isolated from the throats of partners of ♀ who carried BV vaginally, and a history of having ever performed fellatio is significantly associated with M. hominis throat carriage.

Symptomatic culture-proven recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) is associated with cunnilingus, although it appears that isolated episodes are not. Although Candida spp. are found in the mouth, saliva may have an important role in recurrent VVC, as other associated factors include recent ♀ masturbation with saliva and ♂ masturbation with saliva in the past month. It has been postulated that antimicrobial products in saliva could clear local bacteria, providing an advantage to resilient Candida spores, provoking recurrent VVC, have a direct irritant effect or otherwise alter the local immunological state.

Isolated case reports alleging orogenital transmission.

Chlamydial throat infection has been reported in 3.7% heterosexual ♂, 3.2% ♀, and 1.4% MSM, with a significant association in ♀ to ever having performed fellatio. It has also been found in patients with eye infections, which in turn could be caused by contact with infected semen or genital secretions. Symptoms arising from isolated throat infection are extremely unusual and, currently, there are no data on infections transmitted from the throat.

Found in saliva, semen, genital secretions.  infection rates associated with a history of sexually transmitted infections. Considered to be transmitted by kissing; therefore, spread by oral sex is feasible.

infection rates associated with a history of sexually transmitted infections. Considered to be transmitted by kissing; therefore, spread by oral sex is feasible.

Cause of infectious mononucleosis (glandular fever). Classically spread by infected saliva through kissing, EBV has also been detected in semen, cervical secretions, and vulval ulceration. Although unproven, sexual transmission, including oral sex, is a possibility.

Shigella spp., Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., Cryptosporidium spp., Entamoeba histolytica, cytomegalovirus, Giardia duodenalis, and Enterobius vermicularis are all widely reported in MSM as being spread by oro-anal sex or fellatio after insertive anal intercourse ( Chapter 19, ‘Endemic treponematoses’, p. 254). Isospora belli enteritis has been reported in immunocompromised MSM following oro-anal sex.

Chapter 19, ‘Endemic treponematoses’, p. 254). Isospora belli enteritis has been reported in immunocompromised MSM following oro-anal sex.

Oral infection usually involves the pharynx (asymptomatic in >90%), but stomatitis is also reported (following cunnilingus). In patients with gonorrhoea, pharyngeal infection is found in 10–30% MSM, 5–15% ♀, and 3–10% heterosexual ♂. Disseminated infection from a pharyngeal source has been reported. There is clear evidence supporting the transfer of N. gonorrhoeae from the throat to the male urethra, and case reports alleging throat infection from oro-anal sex or kissing. Gonococcal conjunctivitis can arise following contact with infected semen or genital secretions during oral sex.

Rare case reports of oral manifestations suggest that the mouth may be an infection reservoir, but no evidence of orogenital transmission.

There has been an ongoing national and international increase in the incidence of new genital infections caused by HSV1, predominantly in ♀, compatible with the reports of greater rates of oral sex. HSV1 seroconversion in young ♀ has been shown to be directly associated with receiving oral sex and vaginal intercourse. Genital HSV1 infection is associated with receiving oral sex, with a weaker association with vaginal sex, suggesting that it is the partner’s mouth that is the infection source. HSV2 infection can also be transmitted during oral sex causing oro-pharyngeal infection. However, unlike HSV1 infection, oral reactivation and viral shedding are uncommon.

As well as typical herpes infection both HSV1 and HSV2 can cause NGU without visible lesions, with HSV1 more common, and a positive association with the latter, NGU, and oral sex.

RNA (ribonucleic acid) virus found in faeces and typically spread through the oro-faecal route. Studies suggest a link between oro-anal sex and hepatitis A in MSM, with some outbreaks clearly associated with this practice. In addition, hepatitis A may also be acquired by ingesting infected urine.

Hepatitis B virus antigen has been found in semen, saliva, cervical fluid, and faeces although much higher levels are found in blood. Anus-to-mouth transmission during oro-anal sex is considered to be an important factor, especially if there is any local bleeding. Although population studies have shown an association between oro-anal sex and hepatitis B infection, others have failed to confirm it.

Although sexually transmissible, its rate of transmission through this route is very small, and much less than for HIV and hepatitis B. However, it is associated with HIV infection in MSM, especially those engaging in unprotected receptive and insertive anal sex, fisting, use of sex toys, and oro-anal sex.

Studies in MSM have shown that oro-anal sex is a risk factor for KS and HHV8; infection is associated with both giving and receiving oro-anal sex.

Found in saliva at much lower concentrations than in semen and vaginal fluid, but probably  infection risk if local oropharyngeal or anogenital inflammation, ulceration, or bleeding (even after tooth brushing or dental flossing). However, anti-HIV inhibitory factors in saliva, especially secretory leucocyte protease inhibitor from the parotid glands, have protective properties against HIV infection, contributing to >1 in 10,000 risk of transmission via oral sex. The risk is, however, increased by some factors:

infection risk if local oropharyngeal or anogenital inflammation, ulceration, or bleeding (even after tooth brushing or dental flossing). However, anti-HIV inhibitory factors in saliva, especially secretory leucocyte protease inhibitor from the parotid glands, have protective properties against HIV infection, contributing to >1 in 10,000 risk of transmission via oral sex. The risk is, however, increased by some factors:

• very high viral load such as during seroconversion stage in the HIV +ve partner

• ejaculation of semen into the mouth of the person giving oral sex.

These factors should be considered in assessing risk of infection from giving oral sex to a ♂ with HIV infection. Giving oral sex to a ♀ or receiving oral sex from ♂ or ♀ carry very little risk and do not warrant post-exposure prophylaxis.

The development of oropharyngeal warts is uncommon, but when found is usually caused by types 6, 11, 16, and 18, i.e. those most commonly causing genital infection. The development of an oral condyloma attributed to cunnilingus with an infected partner has been reported. High-risk (most commonly type 16) HPV infection is associated with HIV infection (especially cluster differentiation (CD) 4 counts <200cells/mL, oral mucosal abnormalities, and >1 oral sex partner. The natural history of oral HPV infection is similar to genital infection. In patients with oropharyngeal cancer, there is a significant association with HPV type 16 (and oral infection with any of 37 HPV types) with or without the established risk factors of tobacco and alcohol use. The data on the role of oral sex are unclear. Associations with a high lifetime number of vaginal or oral sex partners (with a 250% increased risk for those with >5 oral sex partners) and concurrent oral infection in a sexual partner have been reported. However, other studies have failed to show an association between oral sex and oral or genital HPV infection.

There are no data associating the recent development of LGV proctitis in MSM with oral sex. However, oral lesions and cervical adenopathy due to LGV have been reported following oral sex. Ocular inoculation can give rise to a follicular conjunctivitis, often accompanied by pre-auricular lymphadenopathy.

May be found on the cutaneous lip and peri-oral skin, usually in clusters, especially when immunocompromised. When extensive, often signifies advanced HIV disease.

Although the sexually transmitted nature of non-chlamydial NGU has been demonstrated, an association with oral sex has not been confirmed.

Pthirus pubis may be transmitted from pubic hair to facial hair (i.e. beard, moustache, eyebrows, and eyelashes) during orogenital sex.

• Neisseria meningitidis: case reports and series. Most common—anal infection in MSM, usually asymptomatic. Case reports of urethritis associated with fellatio and cervicitis, vulvovaginitis, and salpingitis in ♀, although asymptomatic carriage more common than with urethral infection in ♂.

• Moraxella catarrhalis: less common than N. meningitidis. Urethritis reported in ♂.

• Streptococcal infection: isolated case reports of acute balanitis following fellatio caused by group A streptococci. Balanitis due to group B infection appears to be related to vaginal coitus.

• Haemophilus influenzae: case reports of H. influenzae-associated septic abortion related to recent oral sex.

The resurgence of syphilis in the UK, W. Europe, and N. America has largely arisen in MSM and their partners. Studies have shown that over a third reported oral sex as the only risk factor, frequently not considering this to be a risk. Oral sex is much less likely to be condom protected compared with anal sex. The reporting of oral sex (often anonymous) among MSM is extremely common, and there is a significant association with higher numbers of oral sex partners, although not with particular oral practices. Kissing as a means of transmission has also been implicated.

Increased bacterial production of cytokines and prostaglandins and amniotic fluid/chorioamniotic infection leading to:

• preterm birth (relative risk 1.5–2.3) from preterm labour and premature rupture of membranes

• 2nd trimester miscarriage (up to 3–6-fold risk)

• endometritis (pre/post-delivery, including Caesarean section).

History of previous premature delivery  risk of further preterm birth 7-fold with BV. Risk of preterm birth higher with BV in early rather than late pregnancy.

risk of further preterm birth 7-fold with BV. Risk of preterm birth higher with BV in early rather than late pregnancy.

Data from clinical trials screening for and treating BV during pregnancy have produced conflicting results. Therefore, current UK (BASHH guidelines recommend:

• Symptomatic ♀ should be treated (as if non-pregnant).

• There is insufficient evidence to recommend routinely screening and treating asymptomatic ♀ attending GUM for BV.

Vaginal prevalence rate doubles in pregnancy to ~40% ( circulating oestrogens and vaginal glycogen). Although not usually associated with chorioamnionitis or preterm delivery, there is limited evidence that eradicating vaginal candidiasis during pregnancy may

circulating oestrogens and vaginal glycogen). Although not usually associated with chorioamnionitis or preterm delivery, there is limited evidence that eradicating vaginal candidiasis during pregnancy may  risk of preterm delivery.

risk of preterm delivery.

Associated with preterm delivery, low birth weight, premature rupture of membranes (PROM), intrapartum pyrexia, endometritis, neonatal infection ( Chapter 9, ‘Pregnancy and the neonate’, pp. 154–155) and post-abortal pelvic inflammatory disease. Screening is advised for those at risk, including those having surgical termination of pregnancy (rates of 2–30% reported). Tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and co-trimoxazole are contraindicated during pregnancy.

Chapter 9, ‘Pregnancy and the neonate’, pp. 154–155) and post-abortal pelvic inflammatory disease. Screening is advised for those at risk, including those having surgical termination of pregnancy (rates of 2–30% reported). Tetracyclines, fluoroquinolones, and co-trimoxazole are contraindicated during pregnancy.

In view of the  risks of preterm delivery, low birth rate, PROM, endometritis, and neonatal infection (

risks of preterm delivery, low birth rate, PROM, endometritis, and neonatal infection ( Chapter 8, ‘Sexual and non-sexual transmission’, p. 140), and post-abortal pelvic inflammatory disease, screening for gonorrhoea is advisable in PROM, septic abortion, intra-/post-partum fever, or those considered to be at risk. Quinolone and tetracycline antibiotics are contraindicated during pregnancy.

Chapter 8, ‘Sexual and non-sexual transmission’, p. 140), and post-abortal pelvic inflammatory disease, screening for gonorrhoea is advisable in PROM, septic abortion, intra-/post-partum fever, or those considered to be at risk. Quinolone and tetracycline antibiotics are contraindicated during pregnancy.

Chapter 31, ‘Streptococcus agalactiae’, p. 346.

Chapter 31, ‘Streptococcus agalactiae’, p. 346.

Pregnancy does not  maternal morbidity or mortality from HBV infection or

maternal morbidity or mortality from HBV infection or  the risk of foetal complications, although preterm labour increases with acute HBV infection. In acute maternal infection the neonatal risk depends on gestational age with 10% transmission risk in the 1st trimester rising to 80–90% in the 3rd trimester. With chronic HBV infection, i.e. hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive, transmission risk depends on maternal infectivity with 90% of infants born to hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg) ♀ becoming chronic carriers compared with <5% if HBeAg –ve and HBsAg +ve. Maternal screening in pregnancy is important as neonatal passive immunization (hepatitis B immunoglobulin) given within 24 hours of birth combined with active vaccination

the risk of foetal complications, although preterm labour increases with acute HBV infection. In acute maternal infection the neonatal risk depends on gestational age with 10% transmission risk in the 1st trimester rising to 80–90% in the 3rd trimester. With chronic HBV infection, i.e. hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) positive, transmission risk depends on maternal infectivity with 90% of infants born to hepatitis Be antigen (HBeAg) ♀ becoming chronic carriers compared with <5% if HBeAg –ve and HBsAg +ve. Maternal screening in pregnancy is important as neonatal passive immunization (hepatitis B immunoglobulin) given within 24 hours of birth combined with active vaccination  the 90% chronic carriage rate with HBeAg +ve infection to 10–15% and with HBeAg –ve infection to <1%.

the 90% chronic carriage rate with HBeAg +ve infection to 10–15% and with HBeAg –ve infection to <1%.

~5% of infants born to HCV-infected ♀ become infected, i.e. serum HCV-RNA detected in at least two samples and/or HCV antibody reactive when the infant is at least 15 months old. Maternal HIV co-infection  the risk of transmitting HCV 2–3-fold. As only 30–50% of infected infants have HCV-RNA detected at birth, it seems that the majority acquire infection at delivery. However, several studies have shown no difference in the neonatal incidence rate with regard to mode of delivery. Although there are contradictory data on breastfeeding it need not be avoided in mono-infected pregnant ♀.

the risk of transmitting HCV 2–3-fold. As only 30–50% of infected infants have HCV-RNA detected at birth, it seems that the majority acquire infection at delivery. However, several studies have shown no difference in the neonatal incidence rate with regard to mode of delivery. Although there are contradictory data on breastfeeding it need not be avoided in mono-infected pregnant ♀.

85% of neonatal infections are acquired perinatally (exposure from infected birth canal), with 5% due to intrauterine exposure (usually ascending lower genital tract infection) and 10% postnatally (contact with family and staff). Risk of neonatal herpes is very low (probably <1%) for ♀ with recurrent herpes. Highest risk is when the mother has not seroconverted by delivery, with a 40–50% risk of neonatal herpes if primary infection is acquired in the 3rd trimester and a 20% risk for initial HSV-2 infection with previous HSV-1 infection.

Oral aciclovir should be prescribed as indicated for initial episodes and intravenous (IV) aciclovir for severe genital or disseminated infection, with case reports demonstrating significantly improved survival of the neonate. It is rarely indicated for the treatment of recurrences during pregnancy. For further information  Chapter 22, ‘Pregnancy and neonatal infection’, pp. 286–288.

Chapter 22, ‘Pregnancy and neonatal infection’, pp. 286–288.

Most HIV transmission risk occurs during delivery and postpartum (breastfeeding), with antepartum (transplacental) spread uncommon. Pregnancy does not  maternal morbidity or progression of infection. In ♀ with asymptomatic infection there is no

maternal morbidity or progression of infection. In ♀ with asymptomatic infection there is no  in foetal malformations or antenatal mortality and only a small

in foetal malformations or antenatal mortality and only a small  in spontaneous abortion, possible

in spontaneous abortion, possible  in low birth weight and preterm delivery. With optimized antenatal/postnatal care and antiretroviral treatment transmission rates are

in low birth weight and preterm delivery. With optimized antenatal/postnatal care and antiretroviral treatment transmission rates are  from 10–40% to <2%.

from 10–40% to <2%.

This is uncommon in pregnancy, but if treatment is required select appropriate antibiotic ( Chapter 14, ‘Pregnancy’, p. 211), try to restrict use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and avoid methotrexate, gold salts, and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) blockers.

Chapter 14, ‘Pregnancy’, p. 211), try to restrict use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and avoid methotrexate, gold salts, and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) blockers.

Syphilis can be transmitted at any stage of pregnancy. In early untreated maternal syphilis preterm delivery or perinatal death will occur in 50% of all maternal 1° or 2° syphilis and 40% of those with early latent infections. With late untreated infection up to 20% prematurity/perinatal death 10% of infants develop congenital syphilis. Therefore, all pregnant ♀ should be screened for syphilis at the initial booking visit.

Early syphilis is treated with procaine benzylpenicillin G 750 mg IM daily for 10 days or benzathine benzylpenicillin, single dose in 1st and 2nd trimester with a second dose after 1 week if treated during the third trimester. Second-line treatments include oral amoxicillin 500 mg with oral probenecid 500 mg qds for 14 days, IM ceftriaxone 500 mg daily for 10 days (limited data) and oral macrolides (erythromycin 500 mg qds for 14 days or azithromycin 500 mg daily for 10 days). However, there are case reports of congenital infection with macrolides, so if used neonatal treatment is required after delivery. Late syphilis is treated as for non-pregnant patients but excluding doxycycline. See also  Chapter 7, ‘Management of positive syphilis serology in pregnancy’, pp. 131–132).

Chapter 7, ‘Management of positive syphilis serology in pregnancy’, pp. 131–132).

There is an independent association in pregnancy with premature rupture of the membranes, preterm delivery, and low birth weight. Although treatment (with metronidazole) is advocated for symptomatic ♀, there is no value in providing antenatal screening and treatment for asymptomatic ♀. There is no evidence that treatment will  the risk of preterm birth and in one trial the treatment of asymptomatic ♀ with metronidazole appeared to be associated with preterm birth. The reason is unclear, and it has even been postulated that it may be due to an immune reaction elicited by the dying TV or virus released from its cytoplasm.

the risk of preterm birth and in one trial the treatment of asymptomatic ♀ with metronidazole appeared to be associated with preterm birth. The reason is unclear, and it has even been postulated that it may be due to an immune reaction elicited by the dying TV or virus released from its cytoplasm.

More common during pregnancy with 2–10% of ♀ having asymptomatic bacteriuria. Without treatment, this persists with a third progressing to acute pyelonephritis. Complications include low birth weight/prematurity, pre-eclampsia, maternal anaemia, amnionitis, and intra-uterine death with risks reduced by treating asymptomatic bacteriuria.

Symptomatic UTI most commonly occurs towards the end of the 2nd trimester because of hormonal changes, although progression to pyelonephritis is uncommon.

All pregnant ♀ should be screened for bacteriuria, ideally by urine culture, although reagent strip testing, although less effective, is cheaper. Asymptomatic and symptomatic bacteriuria should be treated for 7-10 days ( Chapter 21, ‘Management’, pp. 275–276) avoiding aminoglycosides, quinolones, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim (1st trimester). ♀ with acute pyelonephritis should be assessed in hospital as hydration is crucial.

Chapter 21, ‘Management’, pp. 275–276) avoiding aminoglycosides, quinolones, tetracyclines, and trimethoprim (1st trimester). ♀ with acute pyelonephritis should be assessed in hospital as hydration is crucial.

Commonly appear, proliferate, or enlarge rapidly during pregnancy, probably related to relative immunosuppression. There is no known association of human papilloma infection with pregnancy complications and they do not usually obstruct vaginal delivery. Occurrence of Buschke–Lowenstein tumours has been reported occurring during pregnancy.

Treatment options are limited as podophyllotoxin and podophyllin are contraindicated and imiquimod is not licensed in pregnancy, although its use has been reported. As risks are low and regression after delivery is usual, information and reassurance are appropriate for most ♀ affected.

Chapter 2, ‘Sexual offences’, pp. 27–28.

Chapter 2, ‘Sexual offences’, pp. 27–28.

Sexual assault is highly prevalent and often remains undisclosed. Reasons for non-disclosure are multifactorial and may include lack of faith in the criminal justice system, feelings of guilt, fear, and the desire to protect partners and or family. Victims of sexual assault may present to GUM and sexual health services. Clinicians need to be aware of its presentation and the appropriate steps for assessment, referral, and management, including appropriate safeguarding of children and vulnerable adults.

A British Crime Survey showed 19.9% of women and 3.6% of men had experienced sexual assault (including attempts). Of these, 33% of people told no one and only 17% reported the incident to the police. A perpetrator is more likely to be known to the victim than be a stranger.

Latest police recorded crime figures showed an increase of 37% in all sexual offences. The main factors thought to explain this rise are an improvement in crime recording by the police and an increase in victims coming forward to report these crimes. Sexual offences are one of the longest cases to complete in court, reflecting the complexities involved.

The impact of sexual assault on a victim is diverse. Social/interpersonal effects may manifest as strain on relationships or social isolation, but the impact may be far wider on society as a whole, e.g. fear in the community or inability of the victim to work. Associated short-term effects include physical injury (reported by 45% of victims) or other negative health effects (5% report pregnancy and 3% STIs). 61% suffer mental or emotional problems.

Perpetrators often use alcohol and or drugs—drug-facilitated sexual assault (DFSA)—to make it easier to commit sexual assault. This can compromise the victim’s ability to consent to sexual activity through disinhibition and diminished capacity. Drugs used are commonly referred to as ‘date rape drugs’, chosen because they are quick acting, relax voluntary muscles, and have the effects of lasting anterograde amnesia for the events occurring. Alcohol is the most commonly used substance in DFSA and can potentiate the effects of drugs if taken in combination.

Victims of sexual assault may or may not disclose the assault, and may not have any physical signs or injuries. Presentation may be acute within hours of the assault or many years after. Sexual assault referral centres (SARC) in the UK provide assessment and management of victims of sexual assault. SARC functions include:

• discussion of the options available

• taking of forensic samples/gathering evidence in a secure environment

• signposting on for medical care and psychological support

• STI screening (in some centres) or onward referral to GUM/Integrated sexual health (ISH) services.

Multiagency work is key in the management of sexual assault with appropriate sharing of information and ongoing support/aftercare arrangements.

• Facilitates disclosure of sexual assault

• Boosts confidence in the criminal justice system

• Improves short- and long-term effects in victims

• Reduces negative health/psychological consequences

Staff should have the relevant contact information for SARCs, and other local support services in order to liaise with or signpost where appropriate.

These may include:

• Police stations/specialist sexual offence police units

• Child protection/safeguarding teams

• Local mental health services

• Voluntary organizations, e.g. Reach, Victim Support, Rape Crisis Centres, Respond, and others

• Multi-agency sexual exploitation (MASE) or multi-agency child sexual exploitation (MACE): these are meetings that are held to discuss safeguarding cases, and attendance by referring clinicians or those involved in the patients care may be required.

• Multi-agency safeguarding hubs (MASH) provide a link between universal services, e.g. schools, healthcare settings, and statutory services, such as police and social care. The aim is to improve multi-agency work and to prevent young people from ‘slipping through the net’. Clinicians who deal with young people should have links with and an awareness of their local hub.

Some initial screening questions will aid in gathering information and inform what steps will be taken in the assessment and management of the case:

• When did the sexual assault occur?

• What type of sexual assault/act occurred?

• Were they competent to give consent?

• Have they reported this to the police/want to report to the police?

• Are there any physical injuries that need medical attention?

In acute presentations, treatment of serious physical injury following assault must take precedence over obtaining forensic evidence. Where this is not relevant, timed samples of blood and urine are important (for alcohol and drug assays), together with oral samples (mouth washings/swabs), which should be taken as soon as possible after the attack to avoid the loss of potentially useful evidence.

The victim should have the choice of an experienced ♂ or ♀ clinician where possible. Ideally, a suitable appointment with minimum waiting time and a private waiting area should be provided. It is crucial to explore victim’s needs and wishes, and ensure that arrangements are in place for anonymous reporting of incidents to the police if they do not want to make a formal charge.

• Reporting to the police and releasing forensic samples/information.

• Remaining anonymous but releasing forensic samples and some information to the police (3rd party reporting).

• Storing all forensic samples and information at the sexual assault referral centre (SARC), in case they want to release them at a later date (self-referral).

• Proceeding with STI screening/GUM assessment without police or forensic involvement.

All clinicians working with young people should be aware of named individuals for safeguarding in their trust.

Forensic examination should be only undertaken by those who are forensically trained, with the correct equipment and in a suitable environment to decrease the chance of DNA contamination. Forensic examiners have both a therapeutic and forensic role. Examination is top to toe, documenting any injuries/other findings on a detailed body chart, and taking of appropriate swabs to try and detect any DNA from the perpetrator. Colposcopic examination, where appropriate, may be performed to record any injuries in the anogenital region.

If the victim wishes to proceed with forensic examination, they should be advised about the importance of preserving evidence. Where possible, keep clothing unwashed and sanitary wear, avoid brushing teeth, drinking liquids, and bathing or washing. If DFSA is suspected, hair should not be dyed as this may interfere with hair analysis for toxicology.

‘Early evidence test kits’ are available from the police and in A&E, and these should be used as early as possible. The kit includes a mouthwash, mouth swab, and urine sample that can be obtained and kept for evidence where required. Advice should then be taken from the local SARC as to whether a forensic examination is appropriate.

If reporting the sexual assault to the police, defer examination and screening for STIs until after forensic examination to protect evidence. It is possible to have a forensic examination at the local SARC without police involvement (self-referral).

The management of victims of sexual assault should include:

• Consideration of emergency contraception.

Medical evidence may be required in court and well-written documentation in the notes is vital. Use of a pro forma can ensure all necessary information is recorded and no vital areas of management are missed.

In addition to the standard history, detailed information is needed regarding the assault and should be approached in a calm and sensitive manner. Asking a patient to give full details of an assault can be very distressing and the patient should only disclose as much information as they feel comfortable with.

• Presenting/associated symptoms: e.g. vaginal/anal pain, bleeding, bruising.

• Date/time of assault: essential for determining when STI screening should occur and the need for emergency contraception.

• Location of assault: to assess the background prevalence of certain STIs, especially if the attacker is a stranger.

• Perpetrator(s) details: Assessing the risk of the acquisition of STIs:

• if known—any risk factors in perpetrator for blood-borne viruses, HIV, hepatitis B/C.

• Associated physical violence.

• Was assault reported to police? Does the victim want to report?

• Has a forensic examination been performed? Important as forensic examination should be performed prior to STI screening.

• Were alcohol/drugs taken prior to attack? To establish the possibility of DFSA.

• Is the GP aware of the assault and/or a rape support agency been contacted? To assess any treatment given and psychological support arranged.

• Details regarding type of attack: to determine the exact nature of the attack for legal purposes and the risks/sites of possible STIs or injury:

• Physical injury (new or old)

— Vagina, anal, oral, digital/penile penetration

— Sexual history (before/after assault).

NB: Those assaulted may be too upset to recall this information or may have blanked out the detail as a means of coping. Therefore, it is wise to offer screening from all sites and this may provide additional assurance to the patient.

• Past medical/surgical history.

• Gynaecological, contraceptive, obstetric history.

• Medications: prescribed, over the counter, drugs of abuse, and allergies.

• Family circumstances, children—it is important to ensure that the patient is safe from further assault once they go home.

• If the victim has children—their safety must also be considered and, where relevant, a discussion had with the local safeguarding team.

This should be performed sensitively and in privacy, with the victim’s consent. In recent assault cases, the presence or absence of visible trauma should be clearly documented with the use of body mapping/diagrams.

• General state, including any signs of intoxication; general behaviour.

• Height, weight, body mass index.

• Observations: blood pressure, heart rate.

• Both sexes: examine the mouth in cases of recent forced oral penetration to look for signs of injury, e.g. haemorrhages on the palate.

• Female: examination of the genitalia looking for signs of injury or infection. This may include Cusco’s speculum to inspect for internal signs of infection or injury.

• Male: examination of external genitalia and perianal area looking for signs of injury or infection. Offer proctoscopy if recent forced anal penetration for any signs of trauma or infection.

• Anogenital injury: in post-pubertal, anogenital injury is found in up to a third of those sexually assaulted. Severity of assault is a poor predictor of anogenital injury. However, presence of anogenital injury is considered to carry more weight in obtaining a conviction. The site should be recorded using a ‘clock-face’.

• Bruising: bruising may be difficult to interpret. Appearances may assist in the interpretation of its cause (e.g. bruising from finger-tips).

• Leakage of blood into skin due to blunt trauma:

• Petechiae—bruises <2 mm due to increased pressure (strangulation, etc.), oblique blunt trauma, suction, blunt trauma through fabrics, medical causes (infection, coughing, medication, blood disorders)

• Purpura—larger haemorrhages within the skin

• Haematoma—blood collection beneath the skin.

• Abrasions (scratches—linear, grazes—broad): involve only outerskin layers

• Lacerations (tears): full-thickness splitting of skin, usually irregular and often associated with bruising

• Others: incision, stab wounds, thermal (dry heat or moist heat (scald), electrical, friction, cigarette, fracture.

It is rare for the presence of an STI to legally reinforce a case of rape. It is advisable to do a full screen at presentation to detect any pre-existing STIs. However, it is recommended that tests are repeated 2 weeks after the assault, as early sampling may miss recently acquired infection. (i.e. the window period.) See Table 6.3 for the investigations by site after sexual assault.

Ensure that the patient fully understands what investigations/tests are recommended and their implications. Where possible the ‘chain of evidence’ should be implemented (i.e. every handover of the specimen must be signed, dated, and timed).

As well as a standard STI screen and microscopy, additional specimens should be considered. If the patient does not want serological testing at presentation a serum specimen can be stored. This may help to clarify the timing of any subsequent seroconversion.

• Offer treatment for any infection detected.

• Assess mental state and suicide risk.

• A health adviser can reinforce information given, provide links for psychological support, and clarify the follow-up arrangements. Provide contact numbers of agencies able to provide further psychosocial/emotional support.

Table 6.3 Investigations by site after sexual assault

| Female consenting to examination | Investigation | Site |

| NAAT for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae | From any site of penetration vulvovaginal, throat, rectum. NAAT for N. gonorrhoeae screening is highly sensitive, but should be confirmed by culture for medico-legal purposes | |

| Culture for N. gonorrhoeae | From any site of penetration: endocervical, throat, and rectum (advised even in the absence of forced anal penetration) | |

| Microscopy: only if symptomatic | Vaginal, endocervical, and rectal smears for N. gonorrhoeae Vaginal preparations for yeasts, bacterial vaginosis, and T. vaginalis | |

| Culture or NAAT (if available) for T. vaginalis | Vaginal (only if symptomatic) | |

| Female not consenting to examination | Self-taken NAAT for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae | From any site of penetration vulvovaginal, throat, rectum |

| Self-taken culture for N. gonorrhoeae | Vaginal, throat, rectum | |

| Self-taken culture | Vaginal (only if symptomatic). For yeasts, bacterial vaginosis, and T. vaginalis | |

| Male consenting to examination | NAAT for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae | From any site of penetration: urethral swab or urine, throat, rectum |

| Culture for N. gonorrhoeae | From any site of penetration: urethral, throat, and rectum | |

| Microscopy: only if symptomatic | Urethral and rectal smears for N. gonorrhoeae | |

| Male not consenting to examination | Self-taken NAAT for C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae | From any site of penetration: urine, throat, rectum |

| Culture for N. gonorrhoeae | From any site of penetration: urethral, throat, and rectum | |

| Male and female | Syphilis serology | |

| HIV serology | 4th-generation test HIV antibody and p24 antigen | |

| Hepatitis B virus | ||

| Hepatitis C virus | If victim has risk factor, assailant unknown, or if assailant known to have risk factor | |

| Storage bloods | If victim does not wish baseline testing. |

• Emergency contraception: if indicated.

• Prophylactic antibiotics: consider for chlamydia and gonorrhoea if the patient cannot tolerate an examination or requires an intra-uterine device for emergency contraception. Disadvantages include unnecessary treatment, risk of re-infection if source was not the perpetrator and no PN performed.

• Hepatitis B immunization: hepatitis B infection is very rare post-sexual assault, but immunization may prevent development of infection for those at risk if given within 6 weeks following an assault.

• HIV prophylaxis: individual risk assessment needed, including type and location of assault and assailant risk factors. If offered, this should be within 72 hours of the sexual assault.

Support: may be provided by a health adviser, specialist nurse, or other agencies.

• Obtain consent to write to general practitioner: important for the sharing of information.

• Review: for follow-up of any infection detected, repeat investigations (to cover ‘window periods’), hepatitis immunization, and psychological support.

To establish:

• exact documentation of injuries

• identification and retrieval of any possible evidence

• relevant illnesses/previous trauma that may affect the interpretation of injuries/evidence.

Document in notes discussion of the concept of confidentiality and the potential disclosure of any documented information to the police if the assault is reported to ensure informed consent is obtained.

Consent must be given for both non-genital and genital examination, and the recording of findings (including photography), the retention of relevant items of clothing, the collection of forensic evidence, and disclosure to police, Crown Prosecution Service, and Crown Court.

An understanding of forensic timescales can help to advise patients and facilitate referral for forensic testing when requested/appropriate.

The sooner that forensic examination occurs, the better will be the evidence obtained. If the assault is recent (i.e. <14 days,) then a discussion should take place with the SARC, regarding the collection of evidence and documentation of injuries even if the patient does not wish to report to the police.

• Digital penetration: <12 hours.

• Blood for toxicology: <72 hours.

• Seminal fluid/soil/fibres in skin: 2 days; 7 days if unwashed

• Urine for toxicology: <14 days

• Documentation of injuries: <21 days

‘Forcing or enticing a child or young person to take part in sexual activities, not necessarily involving a high level of violence, whether or not the child is aware of what is happening. The activities may involve physical contact, including assault by penetration (for example, rape or oral sex) or non-penetrative acts such as masturbation, kissing, rubbing and touching outside of clothing. They may also include non-contact activities, such as involving children in looking at, or in the production of, sexual images, watching sexual activities, encouraging children to behave in sexually inappropriate ways, or grooming a child in preparation for abuse (including via the Internet). Sexual abuse is not solely perpetrated by adult males. Women can also commit acts of sexual abuse, as can other children.’

Reproduced from HM Government. Working together to safeguard children (2015) under the Open Government Licence v3.0.

When a young person presents with a STI, sexual health-related problem or for sexual health advice, consideration should be given as to whether they are being sexually abused or exploited. In view of recent high profile cases of child sexual exploitation, it is now recommended that, for under-16s, a risk assessment is performed to flag up any vulnerabilities or indicators of risk. ‘Spotting the signs’ is a national pro forma developed by BASHH and the young people’s sexual health charity Brook. It provides a framework to help professionals to identify and assess risk and vulnerabilities and can be used in young people up to aged 18 years.

The presence of an STI may be a marker of child sexual abuse and, if sexual abuse is suspected, screening for STIs should be considered. If infection is found in a child aged <3 years for chlamydia and <1 years for gonorrhoea, vertical transmission from the mother is possible so she should be offered STI screening. This may be extended to the siblings and others in the household.

When prepubertal children present, they should be seen in a designated SARC, together with a consultant paediatrician who may be trained in forensic examination or who will work together with a forensics examiner. The paediatrician will usually be the lead for child protection and have links to safeguarding teams in the local area. A colposcope or other equipment for photo documentation of findings should be available. Post-pubertal children who are under 16 may be seen in dedicated children’s services or, if they prefer, in an adult SARC or GUM/ISH clinic. Young people aged 16–18 are seen in an adult SARC or a GUM/ISH clinic.

All GUM / ISH clinics should have:

• Guidelines for the management of children.

• A nominated consultant physician to take the lead for children as part of a multidisciplinary team with access to formal child protection training.

• Details of local child protection policies and procedures.

• Chain of evidence procedures ( Chapter 6, ‘Investigations’, p. 107).

Chapter 6, ‘Investigations’, p. 107).

• Regular audit of adherence to child protection guidelines.

If the child is under 13, they cannot consent to examination or treatment; written consent must be sought from a person with parental responsibility. If the child is between 13 and 16, ideally, they should be accompanied by a person with parental responsibility; they should sign the written consent together. If the child does not want a parent to be involved, an advocate over the age of 18 should be with them to witness consent.

STI transmission, pathogenesis, presentation, and treatment depends upon the child’s age and hormonal status. In view of positive and negative predictive values, the significance of an STI in children requires careful interpretation. It may be used as corroborative evidence to indicate sexual abuse and if there may be medico-legal proceedings, a ‘chain of evidence’ should be in place, so that a sample can be accounted for from the time it is taken until the result is known. If infection is found, test and treat any consensual or non-consensual sexual contacts (with consent), and test (and treat if appropriate) parents when there is a chance of vertical transmission.

This should be performed at baseline, with tests for gonorrhoea and chlamydia repeated 2 weeks after the last penetrative contact (if necessary), and baseline serology for HIV, syphilis, and hepatitis B and C with repeat testing after 12 weeks. If high risk of exposure to hepatitis B or C, repeat serology after 6 months is advised.

NAATs are generally accepted as the gold standard for chlamydia, although they are unlicensed for oropharyngeal, rectal, and urogenital specimens in children. A positive result should be confirmed by a second NAAT (although culture is considered to be the most specific test for chlamydia, it is rarely available). Culture for gonorrhoea is required for legal purposes, although NAAT is more sensitive. Any positive NAAT should be confirmed by culture, where possible.

When testing prepubertal girls (usually <11 years) introital swabs should be used from inside the labia minora, but avoiding the hymen. A trans-hymenal swab (ear, nose and throat swabs are smaller) may be used if the hymenal orifice is large enough to allow the passage of a swab without distress. FVU for chlamydia and gonorrhoea NAAT should be undertaken in boys (and girls if other tests are not feasible).

Physician-taken or self-taken vulvovaginal swabs are sufficiently sensitive for NAAT. Self-sampling can be considered if age-appropriate, and depending on the wishes and understanding of the young person.

Sampling from all sites should be considered for any alleged sexual abuse in view of the fact that there may not be disclosure of all sites of sexual contact. For suspected abuse, decisions should be made on a case-by-case basis.

Table 6.4 Recommended samples after sexual assault

Wherever possible treatment for children should be prescribed within the terms of the product licence. However, some conditions may require drugs not specifically licensed for paediatric use. If in doubt, discuss with local pharmacist.

Can be found in the rectum, vagina, conjunctiva, or nasopharynx of children, and can be asymptomatic. The estimated risk of vertically acquired transmission is 50–70%, mostly conjunctivitis, but up to 15% have infection of the vagina and rectum (which can persist up to 3 years). The risk of chlamydia is 3–17% in sexually abused children and chlamydia was reported in 75–94% of 0–12-year-olds with a history of sexual abuse. Asymptomatic presentation is common, especially girls with cervico-vaginal infection. Sexual abuse is the most likely mode of transmission in a child with chlamydia and an urgent referral should be made to the safeguarding team.

Gonorrhoea is uncommon in sexually abused children with a reported risk of 0–4% (0–2% in UK studies.) In children with non-conjunctival gonorrhoea, sexual abuse was reported in 36–83% of 0–12-year-olds and 90–100% of 5–12-year-olds had sexual contact. Estimated risk of perinatal transmission resulting in gonococcal ophthalmia is 30%.

Most common symptom is vaginal/urethral discharge, but ~45% is asymptomatic. Sexual abuse is the most likely mode of transmission in a child with gonorrhoea and an urgent referral should be made to the safeguarding team.

Prevalence in prepubertal children is unknown, but is thought to be uncommon, reported in <1% of sexually abused children. Regardless of this, sexual abuse should always be considered in children with genital herpes. Auto-inoculation should also be considered. Although there are few published studies to inform whether sexual abuse is the likely mode of transmission in children with genital herpes, where infected children have been evaluated, 1 in 2, and 6 in 8 were found to have been abused. The diagnosis of genital herpes in a prepubertal child necessitates an urgent referral to the safeguarding team. A positive diagnosis of herpes in the mother does not exclude sexual abuse.

The risk of HIV acquisition in sexually abused children depends on the local prevalence. If vertical transmission or blood contamination is excluded, sexual abuse is the most likely source of HIV infection. Most children acquire HIV infection non-sexually, although transmission following assault has been reported. HIV infection in the mother of a child with HIV does not exclude the possibility of sexual abuse.

There is limited evidence on syphilis in sexually abused children. Although it is reported in less than 1% of sexually abused children between 0-–12 years old, children presenting with 1° or 2° stages of syphilis should be considered to be victims of sexual abuse, where vertical perinatal or blood contamination has been excluded. Congenital syphilis is now uncommon in the UK, but this is likely to  with the

with the  prevalence of syphilis.

prevalence of syphilis.

The diagnosis of syphilis in a child under 13 years of age necessitates a referral to the safeguarding team, depending on the stage of infection and evidence of other modes of transmission. A positive diagnosis in the mother does not exclude sexual abuse.

In girls with confirmed infection of T. vaginalis, sexual abuse is likely, although consensual sexual activity must be considered.

Although there is no evidence to inform at what age vertical transmission can be excluded, T. vaginalis, in girls younger than 2 months may be a result of perinatal infection, maintained by maternal oestrogen, although sexual abuse should still be considered.

If T. vaginalis, is diagnosed in a child between 6 weeks and 13 years old, an urgent referral should be made to the safeguarding team. In children over 13 years, it should be considered on a case-by-case basis.

Genital warts are more likely to indicate sexual abuse than previously thought and sexual abuse must always be considered in any child presenting with anogenital warts. In children with genital warts, sexual abuse was reported in 31–58% of 1–14 year olds. The diagnosis of anogenital warts in a child under 13 years of age necessitates an urgent referral to the safeguarding team.

HPV types 6 or 11 can cause genital warts in adults and children, but in children types 1 and 2 (cutaneous) are also found. Although sexual abuse must be considered, e.g. by touching, types 1 and 2 can also suggest possible non-sexual acquisition, including auto-inoculation. If HPV is vertically transmitted, genital warts may present months to years after birth. There is also a risk of laryngeal papillomatosis caused by peripartum transmission of HPV infection from the mother.

The relevance of finding BV in children is unclear because BV is not classified as a STI. Variable rates of BV, from 7% to 34%, have been demonstrated in sexually abused girls. Although Garderella vaginalis has been isolated from the vagina in 4–14% (as for adults) and may be part of the normal flora, it has been shown to be related to an increase in sexual partners in sexually active girls.