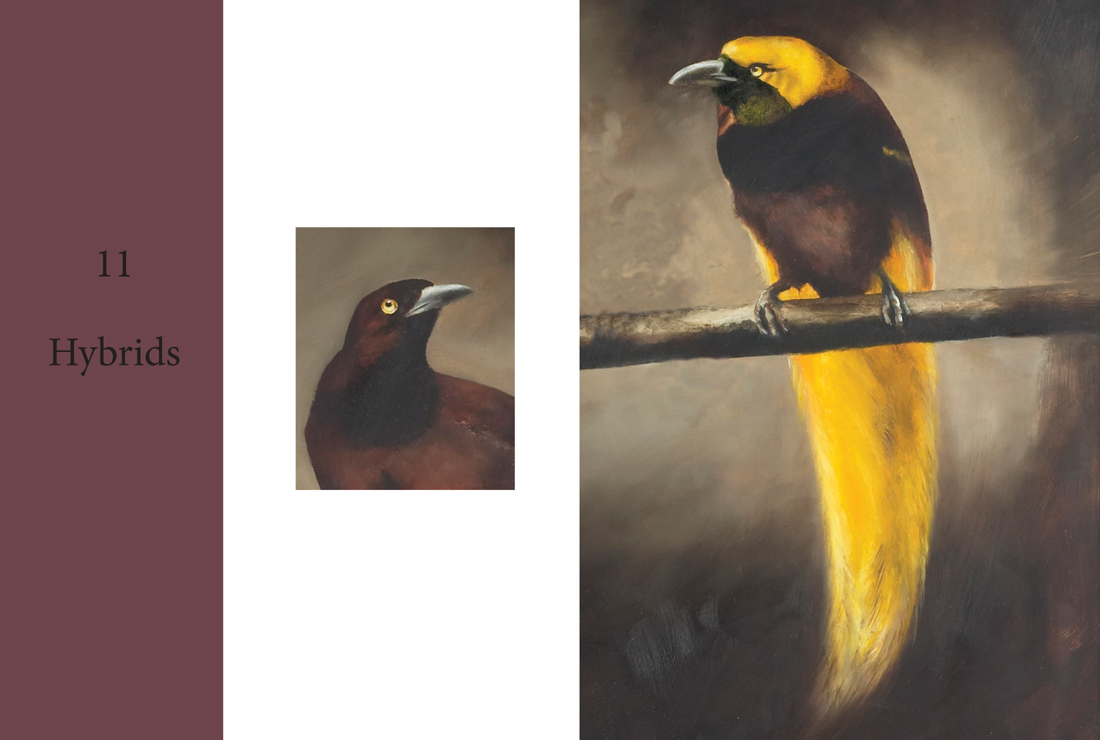

‘Paradisaea mixta’, a male hybrid between the Greater Bird of Paradise and the Lesser, with a female Greater Bird (detail). This hybrid shows the velvet brown breast pad of the Greater and the Lesser’s yellow flash on the wing. Errol Fuller, c.1992. Oils on panel, 55 cm × 42 cm (22 in × 17 in). Private collection.

‘Paradisaea mixta’, a male hybrid between the Greater Bird of Paradise and the Lesser, with a female Greater Bird. This hybrid shows the velvet brown breast pad of the Greater and the Lesser’s yellow flash on the wing. Errol Fuller, c.1992. Oils on panel, 55 cm × 42 cm (22 in × 17 in). Private collection.

Hybrids

It is a general conception that there should be no such thing as a hybrid. Species are often regarded as fixed types that breed only within their own populations, ‘each after its own kind’, in the biblical phrase. For the most part that is what they do, and it is commonly thought that a member of one species will have no wish to mate with a member of another. Even if a mating does occur, it is usually supposed that there will be insuperable physical barriers preventing any successful outcome in terms of offspring. Yet this belief is not reflected in reality, and hybridisation between species certainly does occur. While it may not be particularly common, hybridisation is one of the mechanisms of evolution and it is by no means as rare as might be imagined. It occurs in plants, it occurs in mammals, and it occurs in birds. There is no doubt that it usually takes some kind of special or peculiar circumstance to bring it into effect. But the special circumstances can be many and various and are not necessarily just a question of one individual having no access to others of its kind. As far as birds are concerned, some families (often those that are sexually dimorphic and have polygamous breeding systems) seem more prone to hybridisation than others. The hummingbirds, the ducks and the pheasants are all susceptible to this kind of promiscuous behaviour. And so, of course, are the birds of paradise. Hybrids, however, can often go unnoticed, and it sometimes takes special circumstances to bring them to light.

When the plume trade was at its height, unimaginable numbers of skins and feathers of birds of paradise were sent to Europe and North America every year. These items of commerce came from birds killed by Papuan plume hunters and delivered to merchants in various parts of what is now Indonesia who then forwarded them to Paris, London, Amsterdam, Berlin or New York. Every so often, in among the bundles of skins of the more familiar kinds, specimens occurred (most with no locality data other than that they came from New Guinea) with plumage than didn’t conform to any of the standard patterns.

Were these new, previously unknown, species? Keen-eyed merchants – anxious to maximise their profits – spotted them and sold them at high prices to museums and wealthy private collectors. It was confidently expected that in due course many similar birds would turn up, and that their home grounds would eventually be identified. After all, legitimate new species were being discovered regularly, so there was no reason to suspect that some of these new finds weren’t quite what they seemed. Meanwhile, scientific names were given to each of these new forms and – widely accepted as legitimate species – they passed into ornithological literature.

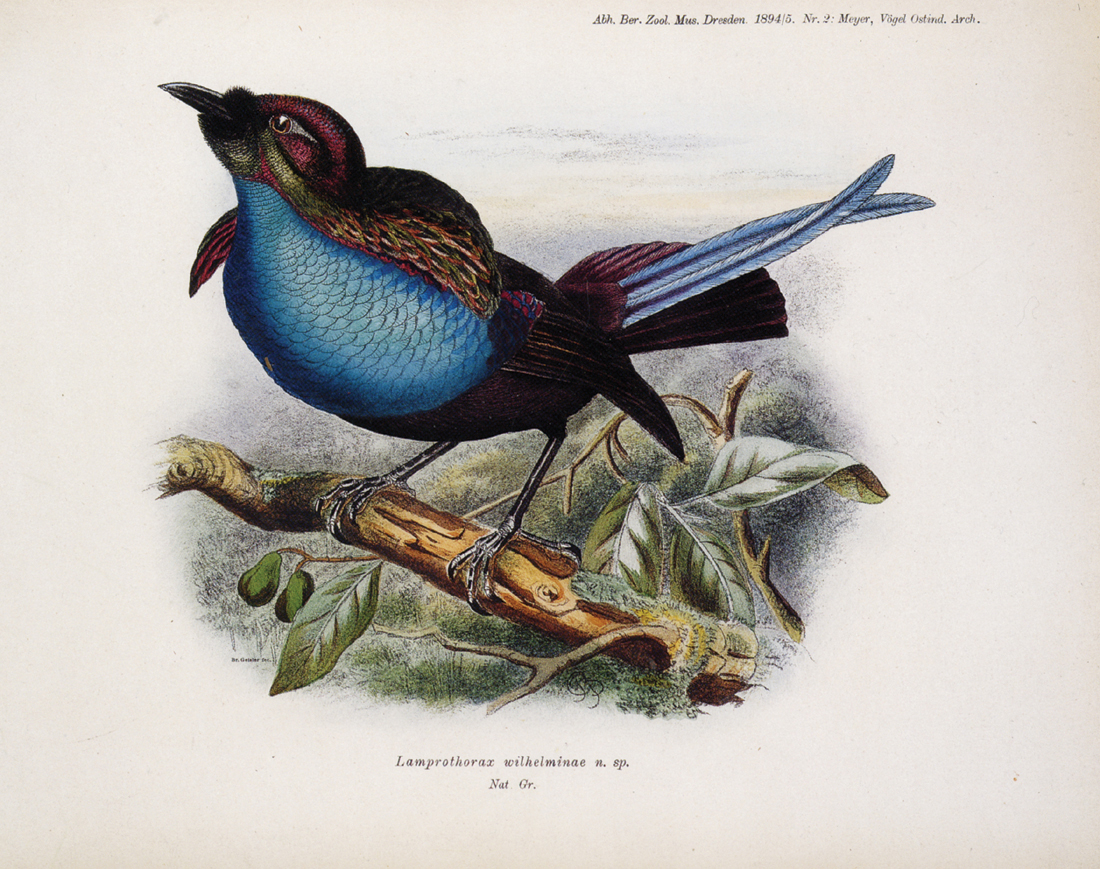

Some of these mysterious new birds of paradise turned up by the plume trade were very spectacular indeed. Take, for example, Wilhelmina’s Bird of Paradise, or Lamprothorax wilhelminae as it was scientifically christened. With a tuft of black feathers at the base of its beak, a purple head and glorious blue breast shield, a cape on its shoulders and two long central retrices of metallic blue, it was named in all its regal splendour, during 1894, after Wilhelmina, then queen of Holland. It was quite unlike any known bird, but with only three specimens (today divided among museums in Leiden, Dresden and New York) having ever been found, was it exactly what it seemed?

As the years went by and the plume trade passed into history, it became apparent that none of these new forms, such as Wilhelmina’s, was being observed in the wild. Suspicions began to be voiced that some might be excessively rare simply because they had a hybrid origin.

At this time there was little appreciation of just how close relationships were between species in the family. Among birds of paradise, there are such astonishing and striking varieties of plumage that ornithologists tended to believe that there were considerable distances between them. In addition, it was not yet realised that the breeding systems adopted by the birds might actually encourage the occasional production of hybrids between species. In fact the breeding systems were virtually unknown; few Europeans or Americans had even seen living birds. Determinations were, therefore, being made almost exclusively from evaluations of dried museum specimens, with little or no background information.

Wilhelmina’s Bird of Paradise, a hybrid between the Superb Bird and the Magnificent. Hand-coloured lithograph by Bruno Geisler from Abhandlungen und Berichte des Königlichen Zoologischen Museum zu Dresden (1894–95).

During the late 1920s the distinguished German ornithologist Erwin Stresemann decided to re-evaluate all the anomalous forms that were known only from excessively rare museum specimens. Stresemann had spent some time among the islands of the South Pacific, but there was only one place to begin his evaluation – and that place was far from New Guinea.

He arranged to visit Lord Rothschild’s private museum at Tring in Hertfordshire, England. Stresemann had a certain amount of contempt for Walter Rothschild who, despite his enormous enthusiasm and zeal as a collector, had no formal qualification in the area of hard science. This, however, is where Stresemann felt he personally excelled. Yet in order to conduct his research Stresemann needed Rothschild desperately, for at that time Walter’s private collection contained more kinds of birds of paradise, including the rare ones, than any other museum. Despite Stresemann’s contempt, which must have been apparent, Rothschild generously allowed the German professor to stay in his house and have the run of his collection. Here Stresemann was able to assemble long series of skins and compare and contrast them, carefully noting plumage similarities and differences.

Having concluded his study, Stresemann once again turned to Rothschild for help, and the article announcing his findings was published in Walter’s own scientific journal Novitates Zoologicae during 1930. It was written in German and titled Welche Paradiesvogelarten der Literatur sind Hybriden Ursprungs? (which translates as ‘Which Birds of Paradise listed in the literature are of Hybrid Origin’).

Stresemann had come to the conclusion that no less than 17 of the ‘rare’ forms were not legitimate species, but were hybrids. He proposed that they were the result of crosses between better-known kinds, and he suggested a parentage for each one.

There need be no doubt about most of his designations. They are correct, and the ornithological world immediately accepted them as such. At a stroke 17 species were struck from the records, and they have remained so.

However, despite the value and truth of most of his decisions, the learned paper that Stresemann produced to announce his findings was couched in very cryptic terms. Many ornithologists have assumed it to be satisfactory in all respects without ever having actually read it, yet it has a number of inadequacies.

Even one of Stresemann’s closest associates became confused. His celebrated pupil, the evolutionary biologist Ernst Mayr (1904–2005) – renowned for his thoroughness and methodical approach – gave his old teacher full support, yet proceeded to create an entirely new genus, Astrapimachus, for a bird he believed to be a hybrid.

One voice in particular was raised in protest. An Australian museum worker named Tom Iredale (1880–1972) questioned Stresemann’s determinations, but his books, Birds of Paradise and Bower Birds and its follow-up Birds of New Guinea, both published in Australia during the early 1950s, are so eccentric that they have largely been ignored.

The influential American bird of paradise expert Ernest Thomas Gilliard (1912–1965) also expressed reservations. But he died suddenly and prematurely and never finished his researches, and his authoritative work, also titled Birds of Paradise and Bower Birds (1969), was published posthumously.

The fact is that, despite any shortcomings in his paper, Stresemann’s findings have survived the test of time. Not only has none of the birds he discussed ever been found in the wild, but there are now many arguments concerning habits and behavioural patterns that can be advanced to support the likelihood of hybridisation within the family. Several species have actually been observed to hybridise and produce forms that were entirely unknown in Stresemann’s time.

Princess Stephanie’s Astrapia, for instance, has been seen to cross with the Ribbon-tailed Bird of Paradise in a hybrid zone where the two species come into contact. This zone was found at Yanka in the Central Highlands by Fred Shaw Mayer, the man who was so instrumental in the initial discovery of the Ribbon-tail itself.

The offspring are fertile and can cross back with either of their parent species, resulting in a variety of plumages, some of which are approximately intermediate, others of which tend towards one parent or the other. This hybrid, in its various forms, has become known as Barnes’ Astrapia.

Various combinations of plume bird are known from museum specimens, and the form known as Paradisaea mixta is a good example. But they are not just known from dried specimens in museums; hybrid zones, just like the one in which Barnes’ Astrapia occurs, have occasionally been found in the wild, and subtle variations in plumage occur.

Barne’s Astrapia, male. Errol Fuller, 1993. Oils on panel, 28 cm × 13 cm (11 in × 5 in). Private collection.

Duivenbode’s Riflebird. Hand-coloured lithograph by J. G. Keulemans from Ibis (1890).

One of the more interesting of the birds dismissed by Stresemann as a hybrid is called Duivenbode’s Riflebird, after the merchant who first brought it to attention. Originally given the rather glorious scientific name of Paryphephorus duivenbodei, it is known from just three museum specimens (one of which exists at the Tring Museum, another at the American Museum of Natural History, New York, and a third which was once in Dresden, but which was lost during the upheavals caused by World War II). Curiously, there is some evidence that suggests that this form, although known only from these museum specimens, occurs in a specific hybrid zone. Unlike most of the excessively rare kinds discussed by Stresemann, there is specific locality data for the two specimens that are still in existence.

Stresemann alleged that the parent species are the Superb Bird and the Magnificent Riflebird, and the plumage evidence certainly suggests that this might be the case. Yet these two birds live at different levels in the forest – the Superb lives at heights well above those generally frequented by the Riflebird. It is, therefore, a curious fact that the two existing museum specimens were taken within just a kilometre or two of one another – yet 34 years apart – in the Owen Stanley Mountains of southeast New Guinea. One of them was actually collected by the same Fred Shaw Mayer who was responsible for locating the hybrid zone that produces Barnes’ Astrapia.

Is there some special factor operating in this area that allows Superb Birds to descend to the territory of the Riflebird, or vice versa? Or perhaps the birds aren’t hybrids after all but a legitimate species with a very restricted range?

The frequency of the production of hybrids like Barnes’ Astrapia, and in particular the continuing viability of some of them, raises an interesting possibility. Is it feasible that in the right circumstances such hybridisation might eventually result in the creation of entirely new species? If the zone of overlap that allows the production of fertile hybrids became isolated from the terrain supporting its original parent species, then presumably the hybrids would continue to breed freely. In time they might evolve into a form very different from their originators. This in itself raises a curious possibility. Did any of the species we now recognise originate in such a way?

Since the time of Stresemann several additional hybrid forms have come to light. Perhaps the most interesting of these is a bird that has come to be known as Captain Blood’s Bird of Paradise. The spectacularly named Captain Neptune Newcombe Beresford Lloyd Blood (1907–?) was a patrol officer in the highlands of New Guinea during the 1940s and 1950s. During his time in the country, between rescuing downed World War II pilots from the Japanese war machine, discovering a new species of orchid and turning 8 ha (20 acres) of New Guinea into an English country garden, he collected many bird of paradise specimens that he sent to the Australian Museum in Sydney. Often he was accompanied on his expeditions in the Mount Hagen area by his very young blond-haired daughter, and on one of these expeditions he discovered a unique specimen – a bird that appears to be a cross between the Blue Bird and Count Raggi’s.

Captain Blood’s Bird of Paradise. Errol Fuller, 1993. Oils on panel, 35 cm × 25 cm (14 in × 10 in). Private collection.

Long before Stresemann’s time, or Captain Blood’s, Jacques Barraband produced some very mysterious watercolours among the illustrations that he painted of more familiar birds of paradise. Two show an individual, or individuals, that are very close in appearance to Twelve-wired birds, but another is similarly enigmatic. It shows an individual that seems to be either an immature or a female of a plume bird species, but it reveals a colour pattern that is quite untypical. It could be a freak, it could be a hybrid.

These are not the only mysteries, however. Among Stresemann’s designations are three that stand out as particularly unsatisfactory. One of these, Elliot’s Bird of Paradise, is discussed in Chapter 6: Sicklebills. Another was given the name Loborhamphus nobilis, the Noble Lobe-bill. Known from just two museum specimens, both now in the American Museum of Natural History in New York, this strange creature was considered by Stresemann to result from matings between the Superb Bird and the Long-tailed Paradigalla. But the combination of features that the two known specimens show is too complex to unravel so glibly. No completely convincing conclusion can be reached from a study of the plumage evidence alone, and any two species selected at random from a dozen or so could be nominated as putative parents. Stresemann’s conclusion is no more than a guess, an attempt to force an enigma into a shape that fits a theory. He may be right, of course, but on ethological grounds alone the pairing seems unlikely. There is no particularly close relationship between the proposed parents, and in appearance the sexes of Paradigalla are virtually identical, while those of the Superb Bird are entirely different. While this in itself would not make a crossing impossible, it certainly makes it rather unlikely.

A curiously plumed immature bird that bears some relationship to a Lesser Bird of Paradise. Jacques Barraband, c.1800. Watercolour, 52 cm × 38 cm (21 in × 15 in). Private collection.

The Noble Lobe-bill, a hybrid or a lost species? Hand-coloured lithograph by H. Gronvold from Novitates Zoologicae (1903).

Equally unsatisfactory is the case of the bird known as Bensbach’s Bird of Paradise. Originally named Janthothorax bensbachi, it is known from a unique specimen in the Leiden Museum. Stresemann decided that this specimen resulted from the illicit mating of a Lesser Bird of Paradise with a Magnificent Riflebird.

Bensbach’s Bird of Paradise, perhaps a hybrid between the Lesser Bird of Paradise and the Magnificent Riflebird – or perhaps not. Hand-coloured lithograph by J. G. Keulemans and W. Hart (after a painting by Keulemans) from R.Bowdler Sharpe’s Monograph of the Paradiseidae (1891–98).

The earliest-known picture of an anomalous bird of paradise, showing plumage that conforms to that of no known species. Attributed to Zacharius Wehme, c.1590. Watercolour and body colour on paper, 51 cm × 29 cm (20 in × 11½ in). Staatliche Kunstsammlungen, Dresden.

His explanation for this assumption was brief, and extraordinary:

Völlig geschwarzte Unterseite und die Qualität des Schillers an verschiedenen Regionen des Gefieders schliessen Seleucides aus und zeugen für Ptiloris.

(Completely blackened undersides and the quality of shimmer in various parts of the plumage, exclude Seleucides [Twelve-wired Bird] and point to Ptiloris [Magnificent Riflebird]).

Quite why blackened underparts should prove the guilt of the Magnificent Riflebird is unclear; no less than 20 other bird of paradise species show this particular characteristic. The remarks about quality of shimmer are no more enlightening; one of the trademarks of birds of paradise is their beautiful array of sheens and glosses. The single individual now part of the collection of the Leiden Museum may or may not be a hybrid, but it is truly an enigma.

But ornithology has moved on, and the argument is now largely academic. Stresemann’s masterpiece of ornithological detection might have balanced perfectly had he not pursued his well-conceived general hypothesis to a positive conclusion in each individual case. That the birds of paradise hybridise to a degree that is not typical of birds in general cannot be doubted. Whether all of Stresemann’s designations are as accurate as they have been held to be is another matter.

Eventually, advanced methods of analysing museum specimen tissue may provide conclusive evidence of whether or not New Guinea’s forests still harbour species additional to those we already know of in the most spectacular bird family in the world. Who knows?