The relationship between things is more important than the things themselves.

—Jean Mitry, Esthétique et psychologic du cinéma

IN CHAPTER 1 I ENGAGED WITH THE PHENOMENOLOGICAL relationship between the film image and human perception; in the last chapter I moved away from strict film analysis to dive deeper into the connection between philosophy and film semiotics and, more specifically, where they might meet in a theory of film connotation. This meeting place, I will continue to elaborate here, is intricately and inevitably linked to the relationship in film between an order of meaning and a system of reference. An analysis of Godard’s films led me to conclude that the transcendental subjective position is only one of many possible origins of meaning within the immanent field of the film image and that the organization of such subject positions can be considered a function of what I have called connotation. This connotative foundation, as we have seen, prefigures narrative and linguistic functions of film, and thus it is with the immanent field of the form itself that we must begin an analysis of film and philosophy. But doesn’t film form include more than just visual elements?

In this chapter I will focus on codifications of speech and image and how they are built according to connotations of the relationship between the diegetic speaking subject, the status of the image as a function of time, and the representation of memory. I will argue that time is as important a factor as space in the construction of filmic subjectivity, and I will invoke Deleuze’s philosophy of cinema to extend Merleau-Ponty’s concerns of spatialization and vision to an analysis of temporality and the sound-image code, a theoretical step that I will illustrate through a close reading of the films of Alain Resnais. Introducing the philosophical notion of intertemporality into film semiotics under the heading of the “crystal-image,” Deleuze elaborates on Bergson’s principles of time: the past coexists with the present that it once was and preserves itself in each new present as “the past”; and, binding these two, time doubles itself at each instant into the present that passes and the past that preserves itself.1 This nonclassical conceptualization of time resonates within certain forms of film editing, such as the flashback, which themselves typically rely on the codification of speech and image to provide a particular order of meaning: an “order of meaning” in that speech evokes a complementary meaning in the image or vice versa, and an “order of meaning” in that such patterns are conventionally built to maintain a stable connotative relationship between system of reference and worldview. But Resnais offers many variations on this code, and in his films these variations saturate the immanent field with a dialogic interaction of different subject-functions, thus forging new formations of interaction between subject and world, experiments in cinematic thinking based on distributing the sensory roles of vision and sound across an intertemporal crystal.

In “Is the Film in Decline?” Roman Jakobson suggests that the difference between auditory signs and visual signs rests not in their degree of importance but in their function.2 In a way, though, they both lead to the same end. That is, in the framework of this book I can rectify this difference through their mutual attempt to organize subject-object relations. Yet there is some truth in Jakobson’s assumption, voiced by others as well, that vision is spatial while sound is temporal, at least in their means of constructing sets of differentiation and organizing relations. And, following Jakobson’s suggestion that sound be understood primarily as an element of montage, let me consider to what extent film signification—as a product of montage within the image, between shots, and as an entire order of meaning—is based on the division and unity of aural and visual expression.

Comparing different compositions of the flashback (and, later, the flash-forward) in light of Bergson’s claims about time will help to illustrate how speech and image interact in the representation of intertemporal modes of thinking such as memory. The sensory elements are divided among different gradations of objective and subjective discourse, and the calibration or dissonance in this interaction is essential to the stability of a system of reference and, through it, the preservation and perpetuation of an order of meaning. Although Deleuze does not necessarily frame Bergson as such, in this chapter I will look at Bergson’s intertemporality as an insight into the dynamics of film’s immanent field, a key link between film and philosophy that is particularly prominent in Resnais’s films.

Having looked primarily at the absent viewing subject of the apparatus, I will now look at the human subject as represented in the text, a character that is implied as the source of the image or its elements: the diegetic subject. Whereas Godard deconstructs the detached subject of objective representation, Resnais does so with the diegetic subject and the subjective mode of representation. Resnais’s films are particularly interesting here because of the great diversity and scope with which they use speech, different codes—dialogue, voice-over, offscreen voices—struggling for domination of the text’s order of meaning, thus reflecting on a range of formal problems concerning the organization of the image and its source of enunciation. To expand this study, it will be necessary once again to add to my arsenal of formal concerns. While I view Martin Schwab’s criticism that Deleuze is “insensitive to the specificities of cinema” as an exaggeration, 3 I do believe that Deleuze’s analysis of types of image-combination is indeed incomplete in its ocularcentric focus on the visual aspect of cinema. However, Deleuze does devote the last chapter of his second book to the relationship between speech and image, indicating that his film project would be well complemented with subsequent consideration of how these elements interact.4 While scholars such as Patricia Pisters and Gregg Redner have made recent contributions to the study of Deleuze and sound,5 I hope to ground this intersection in a more systematic view of how sound and, in particular, speech, functions within the immanent field and is crucial to the configuration of subject-object relations.

The relationship between language and film is a problem that has long been dominated by two focuses: the question of meaning created through dialogue, and the question of whether film is itself a language. That is to say, most critical analyses of speech in cinema, especially concerning Godard (whose use of language has been called a “frequent resort to a kind of verbal delirium”),6 have had less to do with the relationship between speech utterances and the moving image than they have with basic analyses of what people say, the content of dialogue. And, at the other end of the spectrum, as we have seen, much of film semiotics has been dedicated in one way or another to understanding the relationship between film and language as signifying systems.

Inspired by Eco’s notion of cinema as possessing a third articulation, however, I prefer to situate the relationship between cinema and language as a more formal problem that is centralized within the question of cinematic codes and, on the level of signification, the attempt to reconcile sensory data to internal thought, or to use spoken words to create, to contradict, to support, or to alter the meaning of visual images. An analysis of shot and montage must be integrated into an analysis of film as a speech-image construct, just as the objective mode (signifying a detached transcendental subject) must be reconciled to the subjective mode (signified in the form of a character). For, these systems of reference coexist as modes of discourse within the same image and as image-types within the same metadiscourse, problems I hope to elucidate through a comparative analysis of two films by Resnais, Hiroshima, mon amour (1959) and Last Year at Marienbad (1961).

SPEECH-IMAGE CODES AND THE HIERARCHY OF SENSES

Before extending these concerns to larger referential metacodes (the code of subjectivity and the code of objectivity), I will in this chapter redirect my analysis to focus on the codification of speech and image, the conventionalized relations between spoken word and visual image that guarantee the coherence of filmic subject-functions. I hope to use the notion of code to extend this work beyond psychoanalytic and ocularcentric studies of the apparatus and toward the problem of when the image is structured as the implied product of a diegetic character and not just a transcendental subject. While it may not be fully self-evident, and is not frequently acknowledged, the filmic relationship between speech and image constitutes a code on the most basic level: the transposition or passage of subjectivity and signification between one sensory element and another. This includes any method by which speech and image are aligned in order to permit some form of transformation between the two sensory systems, whether from the aural to the visual or vice versa—a code at work, for example, in the immanent field of the galactic coffee cup from Two or Three Things I Know About Her.

In his Aesthetics: Lectures on Fine Art, Hegel considers hearing and seeing together as rational senses, what Heath translates as “senses of the distance of subject and object.”7 There is a ring of the phenomenological here: these senses help us to orient ourselves, to organize the subjective pole relative to the objective pole—what Hegel might call rationalizing our relationship with the world, and what I would call constructing an order of meaning. In nature perception is contextual, and these senses help us to organize spatial relations; in cinema this contextualization is an operation based on specific formal techniques (sound perspective, visual focus, etc.), and these senses don’t only organize space but also help to signify a source of signification, an origin of meaning, and the harmony of this sensory orientation is crucial to the stability of its order of meaning. In real life, sound and image are often harmonious in a multitude of ways. For example, to hear a voice and to see a person’s mouth opening and closing would be an expected sensory conjunction (which Michel Chion calls “synchronism”); similarly, we see a bat hit a baseball, and we expect to hear a crack as opposed to a splash (which Bordwell and Thompson refer to as “fidelity”).8 In more complex configurations people use words to point to an object we can see; also, we often hear descriptions and consequently imagine a visual image of what is being described. Such natural conditions are simulated by cinematic codes that use conventionalized relationships between sound and image to provide a subject of sensory harmony and, to the chagrin of theorists such as Panofsky and Arnheim, to produce a heightened connotation of realism in cinema.9 Couldn’t we say that this harmonious relationship connotes that the subject-function signified by this denotative fidelity is itself a coherent, monistic subject?

That I began my analysis in chapter 1 with the visual side of this problem is indicative of the preferences demonstrated by most theories of film and modernization. For example, film scorer and historian Hanns Eisler considers that, whereas the human eye “has become accustomed to conceiving reality as made up of separate things, commodities … the human ear has not kept pace with technological progress.”10 The suppositions on which this declaration is founded can be traced to a larger historical phenomenon. The cinematic century unfolded alongside what many call the visual paradigm, according to which both our sciences (empirical as well as philosophical) and mass media have set vision aside as a privileged sense, an ocularcentric dominant ideology that, as Martin Jay argues at the heart of Downcast Eyes, was challenged by the twentieth-century French philosophy for which Merleau-Ponty and Deleuze form two crucial pillars. I hope to extend this challenge here to tendencies in film theory, and in this chapter to balance out the focus on cinematic visuality that I developed in chapter 1.

My ultimate aim here is to deconstruct the popular association of vision and the image with cinematic meaning. Film may have started as a visual form, and may often favor visual expression, but is this really an accurate portrayal? Does not Two or Three Things I Know About Her confront us with the very fact that the immanent field of film representation is a dialogic site for the interaction of different sensory elements? If we pay attention to the construction of meaning in a film, we find that sense is often made as much—if not more—through the use of speech, which we could consider as the diegetic form of pure enunciation: a character speaks, and we listen. Not only do we listen, but the apparatus listens, and often the image acclimates itself to the words issued. This is the case with verbal narration, in which a character’s words denote what is then provided in visual form. My interest lying not in the content of what is said but in the manner in which the sound-image is organized through subject-object relations, it will help to focus on patterns or conventions of ordering speech and image, such as the voice-over flashback, that construct a subjective position to be passed from the apparatus to the spectator in the form of a diegetic subject and thereby fix the meaning produced. How are speech and image distributed to order subject-object relations?

Psychoanalytic models, such as Chion’s, answer this question according to the Lacanian argument that words make order of things and give them names, and thus words are the discursive tool of an enunciating subject-function posed as the origin of meaning.11 However, this causal linearity from word to image, what we could call cinema’s nominative practice, is as inadequately monolithic an assessment as was Heath’s: after all, sometimes created visually and sometimes aurally, film meaning rarely follows the trajectory of only one specific order of sensory discourse. Both senses are part of the immanent field, which is in a constant state of flux as the sound-image bends and transforms. While the psychoanalytic notion of subject-formation can be useful, I am looking at film in Deleuzean terms, as a communications-based model of information and, as such, prefer to put this in terms of denotation and connotation. Roland Barthes argues, in his study of photograph captions and advertisements, that “the primary function of speech is to immobilize perception at a certain level of intelligibility … fixing its level of reading.”12 Speech in film is often used in a similar way, and could thus be viewed as a life preserver for film denotation. Reviving Lesage’s metaphor from chapter 2, speech helps to “anchor” the text’s meaning, or as Paul Willemen puts it: “verbal language is there to resist the unlimited polysemy of images,” to stabilize the meaning of the film sign.13

In extending my claim concerning the relationship between denotation and subject-object relations, one could say that speech helps to guarantee coherence to the referential content by adding a sense of subjective totality. Speech and image are conventionally coded to preserve both a stable meaning and to guarantee the coherence of the source of that meaning. Reaffirming my understanding of this codification as a socio-cultural phenomenon, a process of mythologization, Colin MacCabe and Laura Mulvey assess it as a function of conventional cinema’s estrangement of the spectator from the production of filmic discourse: “This [process of mythologization] requires a fixed relation of dependence between soundtrack and image whether priority is given to the image, as in fiction films (we see the truth and the soundtrack must come into line with it) or to the soundtrack, as in documentary (we are told the truth and the image merely confirms it).”14

While these patterns are not necessarily fixed to fiction or documentary films per se, they are codified so as to collaborate in the signification of a particular system of reference that may be used to connote a certain order of meaning, for example the omniscient neutral narrator of documentary reliability. Does this imply the cohesion of subject-functions to the voice as an aural element, as Chion argues? Aren’t MacCabe and Mulvey suggesting, rather, that there is no specific, inherent fixed order but that an order in either direction is constructed and with certain connotative consequences?

As Maxime Scheinfeigel points out, the visual paradigm has particularly strong roots in cinema, which has been considered “a visual art” ever since its first, silent decades.15 As part of the formalist challenge to cinematic mythology in general, however, many theorists have tried to resist the kingdom of images and the myth of visual purity, denying the dominant position of the image in the semiotic hierarchy of filmic expression. This denial became a central tenet of ideology and apparatus theory, “to call into question what both serves and precedes the camera: a truly blind confidence in the visible.”16 I believe that this study would benefit greatly from rejecting such questions of hierarchy altogether and by looking, instead, at how the senses are ordered in the structuring of the sound-image. Film production techniques, as Mary Ann Doane observes, offer many practical industrial manifestations of an arbitrary hierarchy between the senses (for example, sound technology has been developed primarily with the goal of making certain visual effects possible in the shooting process).17 However useful such analyses have been for revealing the ideological foundation of mainstream cinematic practices, though, I disagree with drastic conclusions such as Chion’s “there is no soundtrack.”18 Speech is not always swallowed by the image, as we will soon find, but considering it so has led many to limit their analysis of film.

Hoping to resist such a bias in film criticism’s historiography, I will now turn my ears toward an analysis of how spoken language is situated in relation to the visual image and how this relationship contributes to the construction of cinematic subjectivity. Moreover, how can speech—the organization of aural meaning, not the content of words—permit film to transcend the classical binaries of self and other, interior and exterior? Where does speech fit into the dialogism of the immanent field? Chion claims that, in cinema, sound does not change dramatically in its own right, but “what changes is the relationship between what we see and what we hear.”19 This relationship is the speech-image code. And, as Mitry points out, as holds true like a gestaltist signet for this book: “the relationship between things is more important than the things themselves.”20 How can experiments with the sound-image code challenge our classical understanding of how we interact with the world and even with ourselves?

SPEECH IN, OF, AND FOR THE IMAGE

In film the use of speech changes according to how the words are connected to the visual image. This is particularly relevant to my analysis of film signification because of its demonstration of the link concerning structures of causality and the order of meaning, leading us to a new twist on one of the great apocryphal philosophical quandaries: what came first, the vocal utterance of the word chicken or the image of the chicken? Cinema answers this question in many different ways, each one with its own connotative organization of the relationship between the speaking subject and the visual image. Many feminist critics with whom I strongly agree view the codification of sound and especially speech, therefore, as a problem of great sociocultural and ideological importance.21 After all, since enunciation is conventionalized in conjunction with the alignment of speech and subjectivity, the notion of film as the condition for enunciation is complicated by any alteration to, or subversion of, this alignment. I find it useful to divide filmic speech into two categories: that which is part of the image, and that which is not. This does not mean diegetic versus nondiegetic, or onscreen versus offscreen; it is also slightly different from ideas such as “fidelity” or “synchronism.” I hope to suggest a connotative difference between speech that is coded harmoniously with the image and speech that is coded in dissonance with the image, at least in terms of classical philosophical and cinematic conventions. There is the use of speech that implies subjective totality, and there is the use that, in what Deleuze calls “the disjunction of the sound-image,”22 creates a dialogic interference within the image itself.

Speech can play an important connotative role, defining the logic by which subjectivity is constructed and the order of meaning that unfolds. The voice-over flashback, for example, is a codification of speech and image used for two major effects: to shift the temporal setting of the story, and to shift the discourse itself into the narrative position of the speaking subject. The immanent field is derailed by one particular character, one voice, signified as speaking subject by the fact that the constancy of this character’s voice renders the temporal shift perfectly coherent. The voice-over’s order of meaning is particularly intriguing because it is used to align the visual content as an expression of the speaking subject’s verbal agency. This presents the construct of a new type of subject, the human subject within the image: the film becomes a simulation of that character’s subjectivity. There is yet another articulation beyond Eco’s, a fourth articulation, as the image is itself a representation of the objective world via a diegetic character’s subjective experience of that world. After all, the voice-over seems to open the human agent to us, implying that the image has a privileged position relative to her or his subjectivity: we are allowed entrance to the interior of the character. The voice-over signifies the representation as attributed to a particular source, a spatiotemporal coherence that links the character’s voice to the perspective of the filmic image. This source, differentiated from the objects seen in the image but not from the act of looking, is what I have been calling the subject; only now we can see it constructed in a different way.

And how does the voice-over provide this process of differentiation, of situating? Chion writes quite a lot about the voice-over or the voice without visual body, which he calls the “acousmêtre.” Describing the acousmêtre as neither inside nor outside the image,23 Chion performs a thorough technical analysis of the voice-over, assessing the recording practices and specific audio characteristics that engage the spectator’s identification with the voice-over, or I-voice.24 Through timbre, acoustics, and other technical elements, Chion helps us to understand, on a level of form, how this audible subject is created for us. Reminiscent of the thoroughness and attention to technical detail of Mitry’s writing, Chion provides a perfect example of how a formal analysis can offer insight into the codification of filmic subjectivity, how the structuring of the immanent field determines from what position it will be entered, experienced. In doing so, one could say that Chion is trying to explain how this codification constructs a certain feeling, or mood, an indication that the image is a type of image. In other words, he focuses on the connotation of film sound.

Mary Ann Doane suggests that the voice-over has a “presence-to-itself”.25 This claim refers to the disembodied voice that, through its signifying process, posits a “phantasmatic body.” I agree partially with Doane but must point out that such a “body” is a metaphor based on the system of reference, a metaphor especially familiar in semiotic and phenomenological approaches, though I will reword this to say that the voice-over signifies a particular composition of subject-object relations: the aural subject-function. As such, this formal cinematic process offers a new level on which a cinematic code constructs a filmic subject-function, how the interaction of two elements provides a particular differentiation between subjective and objective poles. Whether it is structured as inside or outside the image, the voice-over is always within the immanent field, capable of erecting a subject-function while erasing any specific visual identity thereof; instead, the visual representation is signified as being the image projected from the position of discourse that is demarcated by the voice. This is connotative—the voice-over is a form of denotation, a way of framing how the content is offered.

With the problem of spoken language and visualization, one finds the immanent field once again linked to the importance of order, both hierarchical and causal, just as it is in suture theory. As with Jacques Rancière’s notion of audiovisual metaphor, this process can be seen as directly related to the interaction of speech and image inasmuch as speech tries to make things seen and images try to make things heard, contradicting both Heath’s and Chion’s respective hierarchies. However, as Rancière notices, “the problem is that, when a word makes us see, it no longer allows us to listen. And when the image makes us hear, it no longer leaves us to see.”26 In other words, he concludes that secreting a formal element into a code of signification seems to erase the element’s formal, constructed origin. It erases its own footprints, sews together the seams of its construction, and—sutured into that fabric—we believe that we are part of an organic whole, a totality of experience taking place in the structuring of the image. We believe ourselves to be set before a denotation with no connotation. And what happens when this code breaks down, when it is revealed as a construction? As Scheinfeigel points out, conflict in the speech-image code disturbs both the image’s and the spectator’s conventional access to cinematic meaning and narrative logic.27 In other words the system of reference is disturbed and the denotation rendered unstable.

How can this process be assessed? By isolating and analyzing a particular speech-image code and looking at what happens when it unravels. Here I will look at the voice-over flashback, which is perhaps the most common cinematic simulation of memory, a representation of memory as a particular composition of subject-object relations. Luckily for us, Resnais offers a wealth of films in which variant modes of representing memory are central. This also permits me to establish a dichotomy between the two filmmakers in this study. For, whereas Godard’s cinematic reflexivity concerns the transcendental subject primarily as a problem of space or spatialization, for Resnais the deconstruction of subjective unity is forged through temporalization, the intertemporal fragmentation of the diegetic subject.

This shift to Resnais and the intertemporal also permits me to systematize two thinkers who are generally seen as quite disparate. Both Merleau-Ponty and Deleuze, I argued at the end of chapter 2, have the same basic goal of destroying the division of interior and exterior that is central to the classical notion of subjectivity. As a marvelous complement to Merleau-Ponty’s claim that an individual’s interior is bound to other subjects and objects through its exterior existence as a body in the world, Deleuze elaborates on how the human subject is also in a state of dialogism with his or her own self at other times in the virtual past and future. Deleuze illustrates this condition through a reading of films, such as I will look at here, that rely on the subjective narration of a character. Subjective narration usually takes the form of recounting a memory. Since memory is by definition an individual’s impression, and thus classically viewed as divided or isolated from the external world, Mitry points out that it is always subjective.28 Yet in cinema a human’s memory is also part of the immanent field; that is to say, this subjective representation of the past is being narrated in the present-time discourse of the non-subjective moving sound-image, the film itself.

This doubling of time provides a perfect example of where film and philosophy meet, as the relationship between screen-time and story-time provides for a folding of temporalities that makes cinema uniquely capable of challenging classical notions of the human experience of time. As Bergson claims, memory is not just a moment in the past, but it coexists in the present, and its representation is tied directly to the establishment of the relationship between a film’s system of reference and its order of meaning. I will analyze the signifying code of the flashback according to my phenomenological framework of subject-object relations. The fluidity of the flashback, which supplies an overlapping of temporal planes due to its having started, and usually returning, to a stable present, is an organization of subject-object relations challenged by an individual’s fragmented recounting of memory in Hiroshima, mon amour, a collective production of memory in Last Year in Marienbad, and, in the next chapter, a person’s anticipation of virtual futures in The War Is Over.

ALAIN RESNAIS AND THE INTERTEMPORALITY OF DIEGETIC SUBJECTIVITY

Having begun his career in documentary film, Resnais offers across his oeuvre great insight into the filmic construction of time and memory, both of which are often considered overarching themes of his work. In Muriel (1963), for example, sequential shifts between past and present serve as a method for addressing a collective sense of shame (the war in Algeria) by acknowledging that the cause of this shame is still present. The memory remains, both in the form of our silence and in the form of tangible suffering, as well as in the form of the moving image. The exploration of memory is more formally complicated in I Love You, I Love You (1968), for example, wherein the recurring presence of the past splinters the present into a cycle of interpretations contingent on a past that no longer has the anchor of subjective certainty.

Such temporal issues are especially resonant in Resnais’s use of the voice-over flashback, a codification, as I have argued, of speech and image used to align the film message with a particular character’s interior experience. Mitry notes that the use of subjective commentary as a framework for film narration goes back to more classical films like How Green Was My Valley (John Ford, 1941) and Brief Encounter (David Lean, 1945). These films used this code to preserve the totality of discourse as referring to one subject-function, a speaking subject who is also the hero of the story being recounted.29 Such a structure gives the impression that the film is a simulation of the character’s memory, using the stability of a system of reference to guarantee a consistent order of meaning. Remarking on even earlier uses of the flashback, Hugo Münsterberg refers to the flashback as an “objectivation of the memory function” in which the image is structured according to the laws of the mind over those of the external world.30 But does our memory follow the neat and tidy logic of the conventional flashback? I agree with Noël Carroll’s claim, for example, that the conventional flashback’s sequential nature is “phenomenologically disanalogous with imagistic memory.”31 This statement is relevant here particularly because of its claim to a phenomenological perspective; however, I would argue that we can explore it more in terms of subject-object relations than in terms of instantaneous perception. I will use Resnais’s work to illustrate a systematization of these two positions: Resnais offers an experimental mode that, while revealing that this “objectivation” is based on the specific codification of film elements, produces a connotative structure meant to refer to a type of subject different from that of the classical flashback, a subject imagined by Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology and Deleuze’s film-philosophy.

To assess Resnais’s codification of the speech-image relationship, one must consider the variety offered by his texts. Built systematically around the recounting of memories, Hiroshima, mon amour and Last Year at Marienbad set in opposition two modes of speech-image codification: codifications in which the words and images complement each other, refer to each other, lead into each other, or explain each other; and, codifications in which the images and the words are in conflict, rupture, the unanchored flux that is essential to film’s moving image but not always allowed in its final products. In the first case, predominantly in Hiroshima, mon amour, speech is used to transfer information from one character to another (and to us, the viewers). The words often complement—and, in many cases, illustrate—the images, or the visual sequence unfolds according to the verbal narration. The speech-image code provides narrative unity and a source of identification in the central character as the subject of discourse and agency. However, this totality of discourse begins to come undone. Whereas in Hiroshima, mon amour the voice-over is part of a diegetic conversation, in Last Year at Marienbad it becomes lost in a dialogic cross-fading of possible pasts and uncertain presents. The immanent field begins to open up, to include not only multiple subjects but also multiple temporalities. The first film produces a logical and linear mode in which the voice-over signifies a speaking subject via its causal agency over the visual representation; the other codifies speech and image so that the referential content cannot be traced to a specific, isolated subject-function.

I would like to reiterate here that this is not an aesthetic comparison; making use of Sacha Vierny’s exquisite cinematography and Resnais’s signature pacing, both of these films offer a lush black-and-white visual beauty and a ruminative rhythm. This is not an argument that one film is better than the other but, instead, a comparison to establish how the nuanced shift in subject-object configurations can have a dramatic philosophical impact on the larger connotative structure of a film. Much the same as with the comparative analysis in chapter 1, the first of these films offers the possibility of radical subversion, a challenge to classical connotation that it retracts at the end but that is fully realized in the second film.

Hiroshima, mon amour and the Speaking Subject

Hiroshima, mon amour, Resnais’s first feature-length fiction film, heralded the director’s defiance of traditional cinematic expression. The film was instantly seen as a cinematic breakthrough. Marie-Claire Ropars-Wuilleumier summarizes the majority view: “Hiroshima precipitates a rupture of codes; through a forceful cinematographic écriture it dismantles the conventional order of cinema.”32 Although I will avoid the metaphor of écriture (writing) that she develops with regard to what is often seen as Resnais’s novelistic tendencies,33 this observation is a useful introduction to how the film, and indeed Resnais’s work in general, has been viewed. The dismantling to which Ropars-Wuilleumier refers, I will argue, revolves around the problem of subjective stability raised through conflicting speech-image codifications of memory. A film about the communication and incommunicability of memory, Hiroshima, mon amour challenges the myth of subjective autonomy, showing the fragility of a unilateral source of signification whose totality is guaranteed by a linear temporal order. What can be said about film’s subject-object relations when such quintessential codifications of diegetic enunciation as the flashback cease to adhere?

As with most of Resnais’s films, the story here could be seen as a springboard for experimenting with the representation of subjective time; in fact, Mitry proclaims Hiroshima, mon amour the first work to make existential time and memory the basis for the film itself.34 But this is not simply a film that talks about memory and time; it shows and speaks them, a cinematic show-and-tell that is achieved by focusing on the connotative level of signification. The progressively unconventional obscurity of the film’s forms of denotation directs attention to the immanent field. Yet I strongly disagree with Roy Armes’s claim that Hiroshima, mon amour “has no story to tell in the normal sense.”35 The film does tell a clear story, even if it is not told in a conventional way. In fact, the unconventionality of the film arises from the formal conjunction of three stories: (1) the present-tense story of an affair between a French actress (whom I will call “Nevers” [Emmanuelle Riva] as she is dubbed at the end of the film) and a Japanese architect (“Hiroshima” [Eiji Okada]), both of whom are married; (2) Nevers’s self-narrated past, which involves her love affair with a German soldier during World War II, his death, and her long-endured punishment by family and community; and (3) the story of the nuclear destruction of Hiroshima and the new scale of warfare introduced by the atomic bomb.36

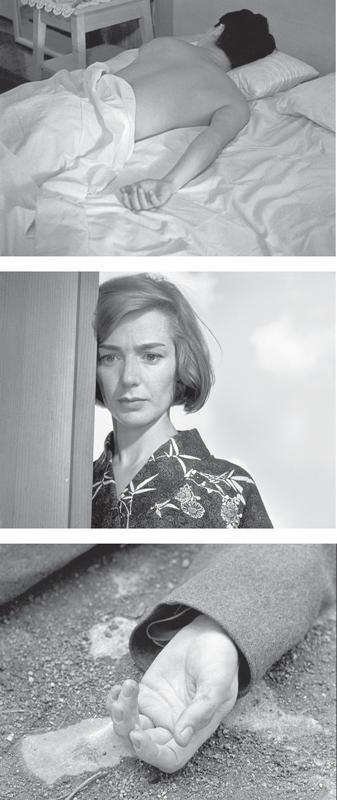

These three stories are interlinked in a complicated form of denotation, a shattered network of sound-images to mirror a shattered world—a postgenocidal and postnuclear trauma of representation that Jacques Rivette claimed to be Resnais’s primary obsession: “the fragmentation of the central unity,” which I understand as the unity posited through classical philosophy’s notion of subjectivity.37 This network of representations is not merely a question of narration, as many would argue, but concerns spoken narration as a means for ordering the image as a type of image. In other words it is a problem of connotation. How are these image-types constructed? Present dialogues use present images as triggers for the representation of memories, memories that begin as spoken words only to transform into image-sequences. Many argue that this is a novelistic convention of cinema, a narrative flow of temporal dimensions that we may recognize quintessentially as the thematic basis for Marcel Proust’s Remembrance of Things Past. For example, the position of Hiroshima’s arm, as he lies in bed, reminds our protagonist of the position in which her first lover died, thus thrusting her back into the past (figs. 3.1–3.3)—which, gradually as the film unfolds, thrusts her into narrating that past.

For Mitry this evokes the Proustian notion of the present as “a privileged instant between memory and forgetting.”38 I would translate this poetic but unclear claim to say that in cinema the present is the temporal praxis for the immanent field through which other temporal subjectivities emanate. The present is privileged as the praxis for enunciation, and this moment is privileged for the speaking subject, who can view herself, her own experience, as a product of her own enunciation. Linking the present with the past through a simple visual shock, she transforms this connection between sensation and memory into a formal cinematic code: the voice-over flashback.

The voice-over flashback, I have argued, reduces the film image to a shared mental image—shared between the narrator, her lover, the viewing subject set in the past, and the immanent field that ties these together—at once both a memory and the communication of a memory. In other words it is an image that within itself casts shadows on multiple points along the scale from subjective to objective. Moreover, it is also, Mitry notes, her own act of looking at herself as an object, which for Mitry is central to memory in both real and cinematic terms. Echoing Münsterberg, as he often does, Mitry refers here to the flashback as an “objectivation of the subjective,” an objective rendering of a subjective experience, which Mitry compares with Proust’s writing in order to illustrate a novelistic aspect of this codification between speech and image.39 Wolfgang A. Luchting poses a complex argument to this effect in “Hiroshima, mon amour, Time, and Proust,” in which he systematically dissects the film according to a narrative structure of different temporal cases (real time, subjective time, etc.), and thus as a complicated representation of “the order of things.”40 This “order of things,” however, avoids the fundamental question of how this order is constructed, not as a sequence of temporal unities but as an immanent field, a collection of interrelationships of specifically cinematic formal elements and interwoven processes of organization. Although narrative experimentation is part of Hiroshima, mon amour, such an analysis does not fully acknowledge how this narration is unique or unconventional: how is this connoted, and how is it cinematic? Beyond the film’s implicit commentary on nuclear warfare, memory, and forbidden love, how do its sound-image forms provide experimental ways of understanding our relationship to the world and to ourselves that transcends the content or object of the text’s analysis?

The film’s focus on history and subjectivity inclines one to follow up, respectively, on more allegorical or psychoanalytic interpretations, such as those offered by Luchting, Ropars-Wuilleumier, and Emma Wilson. While Luchting focuses his analysis on the moral ambiguity of adulterous love, Ropars-Wuilleumier argues that the subversion of codes is an allegory for the sublime and inexpressible magnitude of Hiroshima as a historical event.41 Wilson reformulates this allegorical understanding of the flashback according to a psychoanalytic framework, as “an unwilled returning hallucination or memory that takes possession of the victim of trauma.” Wilson goes on to suggest that the film consists of subjective representations from “a traumatized mind” and that this opening function of the connection between the images of arms exemplifies the importance of bodies and the representation of the haptic in Resnais. She affirms this argument for a visceral reading based on the fact that, in its context in the film, this flashback “serves no explanatory function in the narrative.”42

Wilson is correct in that, at this point, we don’t know who the dead man on the ground is or what the context of that image is. I would argue, however, that this sequence does serve a different explanatory function, as it introduces the film’s paradigm for subject-object relations, the form through which its denotations will be presented. This fleeting cut accommodates us to the system of reference on which the narrative will be founded, easing the film’s immanent field into an alignment with the subjective position of a particular character. In Metzian fashion Wilson makes the connotative analysis secondary to a denotative argument based on the experiences of the film’s main character. On the connotative level, Hiroshima, mon amour is guided by an order of meaning for the most part making use of conventional cinematic codifications of memory. Maintaining aural agency over the unfolding of images, Nevers projects herself as an object in the past while guarding her subjectivity in the present. Typically viewed in film criticism as a text based on fragmentation and struggling discourses,43 Hiroshima, mon amour, I argue, as with Vivre sa vie, poses challenges to classical representation while, in the end, reverting to conventional codifications of subjectivity.

This is the case beginning with the opening scene, in which the film presents abstract images of two intertwined bodies, each of which glimmers with sand crystals, and quickly drifts into a voice-over dialogue (it is a voice-over to the extent that it is assumed that, while the speaking couple may be intimately conjoined, these are not their actual bodies). The sequence unfolds according to a cyclical progression from speech to image, the images following Nevers’s voice-over. She is, quite literally, denoting. Each time she claims to have seen something (first the hospital, then the museum, then the newsreels), we see what she is describing; this image is sometimes even given from the perspective of a moving camera that is directly looked at by people in the frame (fig. 3.4), implying that the shot is constructed according to the individual perspective of a mobile subject.

Hiroshima, to whom she is saying all of this, frequently interrupts to say: “You have seen nothing,” forcing her acousmêtre back to the praxis of the diegetic present, back to the visual context of their bodies. Armes describes this scene as a counterpoint between subjective recollection and documentary modes of representation.44 According to my framework I would argue that here we have an overlapping of different systems of reference. We are seeing images similar to those presented in documentary forms, and sometimes even images from a documentary film, but as the mental image of a character, her memories, as codified through the speech-image relationship. And, the immanent field constantly shifts between documentary-style images of Nevers’s past and objective images of the couple in bed.

Nevers introduces cutaway images with “I saw …,” leading many critics to conclude that the film is about seeing things.45 But the film is less about having seen than about showing, about using a particular codification of speech and image to create a narrative discourse in the diegetic present. It is crucial that the logic of ordering begins not with the visual manifestation of the concept or act of seeing but with the words I saw—a phrase that, importantly, begins with I, a subjective pronoun establishing a system of reference before any claim to action or evidence of this act is provided. While Nevers’s ability to show is manifested in her signaling of subjective images, Hiroshima’s interjections constantly bring us back to the objective pole. This struggle between audiovisual discourse and the physical body raises questions concerning the relationship between signification and physical existence, between the subjective and objective in cinema. Jean-Louis Leutrat, among others, argues that the central theme of the film is the theme of skin, hands, impressions of the tactile.46 This tactile aspect constantly interrupts the codification of speech and image. Nevers is a being in the world, as Merleau-Ponty might say; but our knowledge of her being is coded through film form. The structure of her being is part of the immanent field.

Redirecting these theorists’ argument, then, one could rather see this as Nevers’s coexistence at once as the subject of her own narrated story and as an object in a physical context (which is the text that we are watching). Though it contributes to the dialogic notion of film, this reading of the speech-image code proposes a conventionalized overlapping between perception, memory, and communication (what she has seen, remembers, and tells). Christian Metz’s suggestion that a flashback is like a striptease is particularly poignant here: the more that she reveals, the more that she posits herself as an object of her own narration, the more subjective control she has over the text.47 This codification begins to display its own fragility, however, as the protagonist proceeds further into recounting her own traumatic history. She tells of her German lover and of her incarceration in the family cellar as punishment for the shame caused by her affair with the occupying enemy. Denotatively, this sequence is particularly moving for its allegorical representation of the repression of female sexuality and the dualistic nature of fascism as a function of what Noël Burch calls “the stupidity of the provincial bourgeoisie” during wartime. Burch observes, furthermore, that Nevers’s story unfolds a-chronologically: we see the events not in the order that they happen but in the order that they occur to her, “the stream of her impressions and associations.”48 Burch’s point upholds the common understanding of this enunciation as a conventionalized representation of her attempt to represent her own experience.

We should, however, view this breakdown of denotative linearity as a question primarily of formal—not narrative—subversion. For the sequence to unfold as it does, it must be engendered to do so by the construction of subject-object relations in the form of the speech-image code. During this scene Hiroshima, mon amour encounters short-circuits in the flashback process, blips in the speech-image code that connote imperfections in conventional systems of reference. This is a contradiction between temporal sources of speech and image: the image of the past is still dominated by her voice in the present. We are in the present with the couple. Her voice ushers the visual track into an image of the past, but an objective relationship with that past is never established. The voice-over flashback does not fulfill its role as a code, does not transfer the image from her subjectivity to an objective image set in the past. Resnais’s experimentation with the simultaneity of sound blends objective and subjective poles in a manner that challenges our conventions of understanding and representing memory. The images begin slightly to contradict her narration: she tells about hearing “La Marseillaise” overhead, and we see soldiers passing silently. The speech-image code, whose coherence of enunciation is meant to connote a particular order of meaning, is beginning to splinter.

The division of subjectivity represented by the shift in temporality proves to be too much for the psychological stability of the character. Herein lies the connotative trauma that Wilson’s analysis could have followed through with, as the state of narrative limbo is fundamentally a breakdown in the formal codification of speech and image. As if deeply disturbed by the abovementioned fragmentation of speech, sound, and image, Nevers begins to narrate her memory, a recounting of the past, in the present tense, fracturing the spatiotemporal coherence of her enunciation. The speech-image codification, which is the cinematic sign of her psychological stability, begins to come undone: the image ceases to be linked to her speech.

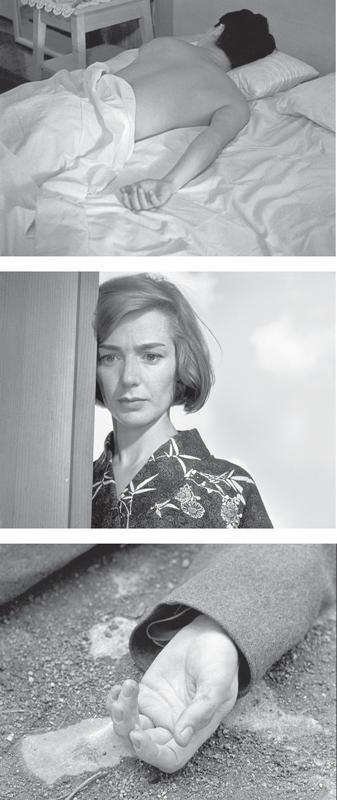

We should therefore understand this as a connotative rupture—not as a rupture in the narrative, which remains relatively stable, but instead with the philosophical ramifications of how the story’s telling is structured, what its telling tells us about the individual as an intersection between past and present and what it is suggesting as alternatives to conventional theories of memory. That is to say: a rupture in the form of denotation, a formal rupture between aural and visual elements that offers us a new way of understanding human subjectivity. This enunciating subject-function begins to splinter further between the past she narrates and the present in which she is narrated, in a scene that takes place between Nevers and her reflection in the bathroom mirror (fig. 3.5).

Her entire discourse deteriorates here into a polysemy of pronouns. She speaks to herself about herself, addressing herself as the first person “I” and also the second person “you.” Beyond addressing herself as possible interlocutor, she interchanges her past and present lovers in the mix of discourses, each of whom at numerous points assumes the mantle of “you” in the present-tense discourse. But her schizophrenia—and therefore the image’s—goes beyond the content of her words. This decomposition manifests itself on the formal level of the speech-image code, as her monologue (or conversation with herself) fluctuates between diegetic speech and voice-over speech. The same thread of speech is continued in these two aural forms, thus presenting the same voice as the source of two different modes of enunciation, a subject split between discourses. The immanent field spreads its wings to mend and encompass the division of the interior and exterior of the diegetic subject.

I should acknowledge here the psychoanalytic importance of the fact that this exchange is happening in a mirror reflection.49 According to Lacan, the mirror phase—one of the most frequently recurring psychoanalytic concepts used in film theory—attests to the stage in human subject-formation in which the infant succeeds at identifying itself as both a visible object and coherent subject. As can be gleaned from the language of the previous sentence, Lacan’s theory projects Merleau-Ponty’s existential philosophy onto a psychoanalytic framework of mental development. In filmic terms this is similar to Mitry’s assessment of the flashback, in which the character verbally posits herself as a visible object in the imagistic representation of her own verbally narrated recollection. In this particular example the codification of that recollection becomes apparent, as if cinema itself were acknowledging its own duality between subjective and objective poles. This mode of self-conscious, reflexive cinema, constructed by Resnais and Godard in very different ways, could well be described as cinema’s mirror stage.

After this scene Nevers attempts to gather the composure of her conventional subjectivity. She walks down the sidewalk with her lover only steps behind, depth-of-field adding yet another mode of organizing the division between them. She tries to reclaim the authority of her enunciating subject-function by reinforcing the causality between her voice-over and the visual representation. “He will walk towards me … take me by the shoulders. He will kiss me,” her voice-over says as they walk. However, he remains distant (fig. 3.6).

Her voice-over is not supported by the visual world of action; she is revealed to be powerless in the present, and her control over the narrative is revealed as a coded representation. This fully rejects any illusion that the image is essentially or naturally connected to the words being spoken. Her interior is made exterior, and the representation is caught between aural subjectivity and visual objectivity, a site for the dialogic overlapping of reference points.

In a textually circular fashion, however, evoking this nominative process marks the film’s return to its original speech-image code, the reconciliation of speech, image, and body found in the opening. In the final scene, after having passed the entire film anonymously, the two characters name each other: she names him “Hiroshima,” and he names her “Nevers.” This act of naming reconciles the film’s speech-image irregularities in a way that supports the conventional subject-function challenged in certain sequences: in the end the human subjects are defined by a nominal logic of differentiation and returned to the objective system of reference held in the apparatus. Just as we saw with Nana’s death in the final scene of Vivre sa vie, Hiroshima, mon amour ends by nullifying its experimental philosophy and returning to an order of meaning founded on traditional rules of thinking.

Last Year at Marienbad and the Dialogic Subject of Collective Memory

Last Year at Marienbad is quite different from Hiroshima, mon amour in that it is not simply divided between the present and the past but between all possible pasts and their contingent presents; moreover, its embrace of an unconventional order of meaning, which does away with the hierarchy between real and imaginary, certainty and confusion, owes the realization of its philosophy to the complex system of reference set up in the film’s immanent field, a transforming flow between the apparatus and two diegetic subjects. This terminology admittedly owes much to Deleuze’s conceptualization of cinematic time, which uses Bergson’s principles of temporal overlapping to understand the temporal fragmentation of a diegetic subject. Indeed, just as Hiroshima, mon amour serves for Mitry as the model for a new type of cinema, Last Year at Marienbad holds for Deleuze a special place: it is “an important moment” in the deconstruction of classical codes and a constant point of reference in Cinema 2: The Time-Image’s exploration of a new film-philosophical outlook that rejects classical paradigms of logic, representation, and the subject-object binary.50

A film about the struggle between two people over a memory of something that may or may not have happened, Last Year at Marienbad, Ronald Bogue points out, can be said to represent a “malleable, non-personal virtual past” composed from the slightly varied repetitions of “memory suggestions.”51 By “non-personal” we can understand Deleuze’s concept of nonspecific film subjectivity, what I have reconstructed as a fluctuation between positions, which is illustrated by this film’s combination of image-types in an overall network of collective memory that includes both the apparatus and multiple characters. Bogue extends Deleuze’s analysis to posit the images as “coexisting strata of time,” a flux that I would describe as the coexistence, in the present, of multiple possible memories.52 This fluid movement between past and present would be impossible without keeping one foot in the present while stopping the other in the past. To do this, a code must be ruptured and divided between the two elements that compose it.

This rupture is accomplished by splicing the speech-image code. We have seen how in Hiroshima, mon amour the splice in this code can permit a sort of time travel, as long as the subject-function driving this time machine is coherent, stable. I will look now at what happens when this time machine loads up on turbo fuel, loses its GPS device, and gets hijacked by another driver. Last Year at Marienbad is built from a system of montage in which the conventional narrative organization of shots is replaced by an interweaving of temporal moments, using certain formal relations to connote the permeable nature of temporal continuity, as well as the crystalline or multilateral nature of film enunciation. This crystal, like that constructed in Two or Three Things I Know About Her, reveals the dialogic capabilities of film’s immanent field. Nowhere is this more apparent than in the synapses between speech act and mental image, a relationship that we could isolate as the central basis for Last Year at Marienbad’s philosophical experiments. The film’s screenwriter and champion of the nouveau roman, Alain Robbe-Grillet, himself wrote in the published version of Last Year at Marienbad: “The entire film … consists of a reality that the hero creates from his own vision, his own speech.”53

The film is about the attempt to denote a visual reality through the use of spoken words; however, the film does not unfold neatly. Last Year at Marienbad is composed of a wide variety of speech-image relations, rarely maintaining a conventional code of present-speech/present-image or even a clearly defined code between present-speech/past-image. But let me start out more simply, with an overview of the film and its critical reception. Though there is admittedly little “story” to go on, there is a general theme of seduction, refusal, and persuasion—what Jean V. Alter aptly calls “a conflict of wills.”54 This conflict of wills manifests itself through opposing mental acts, an audiovisual phantasmagoria that unsettles most conventions of film storytelling, leaving viewers to ask: “What happened?”

As a result of its unique stylistic extravagance and its cryptic order of meaning, Last Year at Marienbad has inspired no shortage of commentary and interpretation. Wilson, for example, views the general unreality of the film as being “about the role of fantasy in supporting desire.”55 Working from Slavoj Žižek’s reading of the film, Wilson interprets the experimental narrative as manifesting the characters’ desire and fantasy: the struggle for volition, according to Wilson, could be seen from this angle as a rape fantasy. Although I will not take a similar psychoanalytic approach, Wilson’s interpretation could be viewed as a variant on my notion of the immanent field, in which we find an interaction between image-types built according to different subject-object relations, struggling to guide the philosophical logic of the film’s metadiscourse. While metaphors of fantasy and dream dominate most readings of Last Year at Marienbad, my model would systematize these alongside more narrative approaches, such as Neal Oxenhandler’s analysis of the text as a symbolic representation of emotion.56

For those familiar with the film, it is without question complex and fecund for interpretation. And, while Last Year at Marienbad’s system of meaning is so vastly open that a multitude of allegorical, psychoanalytic, and symbolic interpretations could be applied to it,57 I will defer to the filmmakers’ insistence that the text is, fundamentally, a reflexive experiment in film form.58 Regardless of whether the unfolding scenes are memories or fantasies, dreams or alternate dimensions, critics such as Jacques Brunius and Haim Callev point out that this debate is made possible by the fact that the film perpetuates no clear system of reference.59 Last Year at Marienbad is constantly unsettled by a fluctuation between the subjective and objective poles, and we are never given a clear structure of subject-object relations; the film dismantles the coded divisions between subject-functions, constructing a reflexive parallelism that implicates in the immanent field the signifying processes between person and person, between character and text, and between text and spectator. As Merleau-Ponty might say, it shows how we show—to others, and to ourselves.

The opening sequence in Last Year at Marienbad introduces the connotative principles that will prevail throughout the film, including audiovisual motifs as well as the thematic instability of the code that binds the audio and the visual. On the visual level the film opens with long tracking shots that capture the luxurious frescoes and gilded trellises of the chateau where it is set, an ornate visual design accentuated by Vierny’s black-and-white photography and a vast array of mirrors and reflections (Lacan, incidentally, first presented his mirror-stage theory at a conference held in the town of Marienbad in 1936). The tracking shot, usually attributable to a specific source, is not attached to an identified subject of vision, so we turn to the audio for such an anchor. But the images flow by hypnotically, apparently without any motivated connection to a soundtrack that is saturated with conflict, an ebb and flow between two aural elements: an organ and a male voice-over that describes the labyrinthine grandeur of the locale. Taking turns fading each other in and out, the aural elements constantly exchange places in the forefront of the sound mix. This produces what David Bordwell calls “the cocktail-party effect,”60 referring to the difficulty of following two aural discourses at once. Though Bordwell relegates this effect to “spoken discourses,” it could be applied here to the disparate sources of enunciation, as these overlapping soundtracks vie for the production of different systems of reference: one that is narrated by a character and another, accentuated by organ music, projected from the apparatus.

At this point, however, neither the voice nor the organ has a diegetic source in the film: we see no organ, we see no body. One could argue that the voice-over, in fact, belongs to the male protagonist (who, following Robbe-Grillet’s script, I will call “X” [Giorgio Albertazzi]), but this is unclear at this stage, as the audience has not seen him. Continuing her argument of the tactile in Resnais’s work, Wilson claims, “Words precede images here, as if the extraordinarily tactile, sentient world of Marienbad … is called up, imagined as a result of the words we hear narrated.”61 However, the scene does not necessarily unfold in this nominative manner: the words follow a cyclical, not linear—or explicative—trajectory and are constantly faded in and out by the music. What I termed cinema’s nominative practice earlier in this chapter, in which the visual image is conjured or described directly by spoken words, is frustrated further by the constant, interruptive return of the organ. Neither of these aural elements exerts a causal agency over the flow of images. The voice-over speaks of being thrust back through rooms and halls, yet the visual pictures are not necessarily connected to the words. For example, the organ softens slightly as the voice-over fades in at a random point in its cycle: “... the lengths of these corridors …” As his voice continues, the shot cuts to a different tracking shot. The new tracking shot moves fluidly as the voice then fades out and the organ fades in: the shift between the two aural tracks has no connection to the cutting between tracking shots. Voice-over narration, nondiegetic music, and the tracking shot are all normally characterized by their fluid formal continuity. But here one continues as the other breaks, shifts, or restarts, thus accentuating the rift between them, belying their own respective lacks of totality. This introduces what Leutrat views as the film’s central theme of repetition and difference.62

This theme escorts us into the scene that follows. The guests at the villa are paired off into couples or trios, and the camera slowly moves through the rooms while the sound records fragments of often unattributed conversation. Following the theme of repetition and difference, a collective discourse is interwoven among the different groups, basic themes of conversation that continue unimpeded from one group to the next. Each group engages in a variation on the incertitude that will come to dominate the interactions between X and the female protagonist, “A” (Delphine Seyrig). “We met …,” “ … when … ?,” “ … where … ?” Watching this clarifies Wilson’s observation that the guests “function as part-animate props” to provide molds for how the film will use speech-image codifications to represent the phenomenon of collective memory and the role of verbal narration therein. A certain process of collective interaction permeates the immanent field: the signifying system from which this film builds its articulations consists of what Wilson refers to as “the social codes which construct identities and social interchange” through repetition and circulation.63 Fleeting claims about “when we met … [and] where … ” are confirmed not by images or even firsthand description but by the narrative assertion that “I heard … ” As I will show, however, in this film, being recounted, being narrated, does not make something factual, does not always lend it certainty. These conversations weave in and out of the voice-over of X, who has now been given a visible body (at least, a body we assume to be his, as he is the only person we recognize in numerous images). His voice-over, too, extends its own permutations on this collective discourse.

This scene introduces A, the female protagonist about whom these hushed voices may or may not be talking, via a conflict between speech and image. Wearing a black dress, A stands in a doorway. Presumably speaking of her, and also to her, we hear X’s voice-over utter the words: ‘Always the same.” The image cuts to A, in the same position, only now wearing a white dress, thus ironically following the speech-act with the visual contradiction of its meaning (i.e., in the second image she is not “the same” as in the first). In Last Year at Marienbad’s dance of repetition and difference, the film tells us up front, we will have to get used to our expectations being dashed. This signals a split that I will argue in chapter 4 is characteristic of Resnais’s oeuvre in general and, in chapter 5, is manifested in different ways in Godard’s Contempt. This split occurs between the sensory aspects of the sound-image, keeping both visual and aural elements present in the immanent field but detaching them from a solitary system of reference. This split signifies a struggle for subjective agency, a multiplicity in the film’s origin of meaning and therefore an experiment in the classical model of logical thought and the totality of meaning. This sensory split, like the aural discourses of Two or Three Things I Know About Her, reveals the text itself as a field for the interaction of possible subjective positions. But in Last Year at Marienbad the sequence of images is not only a site for this interaction: it is a battleground for the war of speech-image agency. This struggle for a closed audiovisual image, for a singular subjective position, takes the narrative form of persuasion: X’s attempt to convince A of their mutual experience by conjuring up an imagistic past with his verbal discourse in the present. But the present is not stable in the midst of forking pasts, possible memories, and conflicting temporal discourses.

This instability results from the fact that, while these temporal fluctuations are linked through the transformation of speech codes, these links do not provide a stable subject of discourse. There is never a definite logical order of meaning infused into the relationship between speech and image: the mode of discourse is constantly changing and, thus, never stabilizing a single subjective agent, nor even a single sensory agent. As Christian Metz writes: “In Last Year at Marienbad, the image and the text wrestle. … The battle is even: the script creates images, the images provide a text: it is this game of contexts that provides the contours of the film.”64 These contexts consist of a constant overlapping between speech functions and visual functions. Contrary to Metz’s assertion, though, I view the film rather as a failure of words to make images and vice versa. The subject-functions of visuality and speech are kept from conjoining, thus denying each other any corroborative certainty or confirmation. For the majority of the film X struggles to convince A of their previous meeting by garnishing visual support for his words, but this agency constantly finds itself at the crossroads of overlapping subjective and objective poles.

We find A, for example, wandering through an open hallway as X’s voice-over speaks of her clothes and gestures. At this point the image seems to be a mental image constructed by his verbal description. That impression is soon shifted, however; the camera zooms in and pans slightly to reveal X himself in the image, his voice-over suddenly becoming an onscreen voice (fig. 3.7). This formal alteration to the immanent field abruptly shifts the system of reference from subjective (though it is unclear according to whose subjectivity) to objective.

Yet this is not the code he wants, for it does not assume an alignment between his speech and her imaginary. It does not align the immanent field to signify him as its unique system of reference. So, again, X returns to conjuring images according to his voice-over. When he gets this wish, however, it is not without its consequences. We see A outside, awkwardly trying to position herself according to X’s description. His voice-over describes how she was standing, and in the image we can see her attempt to accommodate his description. That is: A, in an image that is coded to be set in the past, responds directly to the speech act that is attributed to the present, fully breaking the illusion necessary for a stable denotation either between the characters or between the film and spectator.

This sequence provides the first truly self-conscious rupture in the conventionalization of temporal divisions, self-conscious in that the text acknowledges that it is supposed to work a certain way, that there is a conventional way of structuring film meaning through the order between speech and image that this film is currently violating—it is consciously experimenting with cinematic thought, performing philosophy not through written words but through the tools and codes of cinematic form. The code is brought to the surface; the myth that X is attempting to create is revealed as exactly that, a myth; and the frustration of a closed denotation directs attention toward the film’s connotative base. This myth is then naturalized in the form of an objective image of the two characters, and objectivity is thrown into question by the fact that their conversation continues in voice-over. Again, when one sensory element follows X’s attempt to organize a system of reference, the other sensory element deconstructs it. He tries to keep A at the mercy of his aural agency, the power of his voice-over narration, which exists only through the ability of his words to conjure images. The film returns to the diegetic “present,” in which X’s description of the statue by which they were standing is interrupted by Frank (presumably A’s husband [Sacha Pitoëff]), who explains the historical basis for the statue and, thus, offers yet another subject or source of meaning in the film, another system of reference intersecting in the immanent field.

The centrality of the statue to the multicharacter discourse has led many, including René Prédal, Leutrat, and Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues, to make the argument that Last Year at Marienbad is, in fact, a film about the statue itself.65 In the context of my analysis, however, at most the statue can be seen as a microcosm for the film’s meditation on interpretation and relativity, and merely plays the role of an object of discussion around which the multiple voices can vie for subjective agency. My own argument can be posed as such: there is a problem of denotation, which can be traced to the instability or lack of specificity of a single system of reference, the interruptions and feedback of multiple discourses. The visual tracks begin to intersect here, and it becomes unclear within which system of reference the image is being signified. Does the image belong to A or to X? Even as it seems that she is beginning to remember, her memory is still not the same as his. In this way Last Year at Marienbad offers us a simulation of collective memory, two people trying to reconcile their mutual present to a nonmutual past. As Deleuze observes, Resnais “discovers the paradox of one memory shared by two people.”66 It is important to note that Deleuze uses the word mémoire, which means memory as a mental function, and not souvenir, which refers to one specific memory. These two people have different understandings of some time-space continuum that they may, in fact, have in common; it is just a question of how it is seen, what the logic may be through which they connect to the world—in other words, what their philosophy may be.

This paradox, formally realized through a juxtaposition of aural and visual elements, presents a struggle for authenticity on the level of the speech-image code: subjective agency rests with the character who can determine some sort of sensory causality or harmony, who can establish an affinity with the immanent field, align his or her imaginary with the film image. But in Last Year at Marienbad this codification never succeeds: what began as a singular attempt to persuade becomes a collective challenge to remember. To follow up on Deleuze’s “memory of two,” we slowly realize that the memory being debated, regardless of whether or not they both experienced it at some point together, is “a memory that is communal because it relates back to the same givens, affirmed by one and denied or rejected by the other.”67 This very opposition, manifested in the formal sharing of visual representations, reveals a bond between people. But who is telling the truth? Is there any such thing as absolute certainty, or truth, in the classical notion of subjectivity, which—according to Deleuze—by its very essence implies the divergence of consciousnesses and, between them, the impossibility of consensus?68

The suspense concerning their possible shared past builds toward a climactic confrontation over that pivotal night during which a tryst is claimed to have happened, and a sexual assault is implied as a possible alternative. Standing at the bar, X describes to A his entrance into her room. There is a quick crosscutting between the present moment of description and the past that is being described. In the present A looks at X, finally beginning to adopt his verbal descriptions as her own memory. He speaks of entering her room. In the bedroom A looks up, as if at someone who is entering, and laughs (fig. 3.8). The sound of her laughter resonates through the temporal division provided by the code of montage, continuing on the soundtrack as if escorting the image—and therefore her and us—back into the present, back to the bar, where a female bystander’s laughter replaces that of A (fig. 3.9). The two sounds merge into one experimental sound-bridge, blending two temporalities into one filmic utterance; the immanent field binds the temporalities through its inclusion of formal elements.

The aural element of laughter is continuous, providing an intertemporal unity or totality that breaks A out of the trance of X’s agency, as if from fear of being consumed by his claim to subjective power. The sound-bridge of laughter carries her from the collective imaginary back into the present, where she is terrified at the potential power of his verbal subjectivity. At this point it becomes wholly apparent that these temporal shards, or what Deleuze calls nappes, are not independent of each other: in their Bergsonian coexistence these temporally different sound-images create what Deleuze refers to as a sort of “feedback” similar to that produced by electricity interfering with itself.69 It is through this feedback of multiple utterances, each of which is composed of its own subject-object configurations, that the system of montage deconstructs the conventions of the classical subject and signifies what Resnais refers to poignantly as “a universal present” in which all temporalities collide.70

Terrified, A recoils, bumping into the bystander and knocking a glass to the floor. Her fear in the present is then transferred to her representation of the memory, in which she now expresses fear. In the bedroom A, recoiling in fear, knocks over a glass (fig. 3.10).

Shaking with the reverberations of this feedback, the speech-image code struggles with a transition created by the sentiment of terror being directed from the present backward. In this case, as Deleuze observes: “The characters exist in the present, but their feelings plunge into the past.”71 In fact, both the characters and their sentiments alternate between past and present, present and past, but one is never exclusive of the other. Both emanate through the immanent field. The past affects the present, and the present affects the past—it is all a matter of what, at a given moment, is the system of reference according to which the text is structured.