The photoplay tells us the human story by overcoming the forms of the outer world, namely, space, time, and causality, and by adjusting the events to the forms of the inner world, namely, attention, memory, imagination, and emotion.

—Hugo Münsterberg, Hugo Münsterberg on Film

AS I HOPE HAS BECOME APPARENT IN MY READING OF DELEUZE, this book is not an indictment of subjectivity or filmic subjectivity. As Martin Schwab points out in discussing Deleuze’s film writing: “the subject is not an anomaly—it is cosmic normality, no matter how unlikely its emergence.”1 But between the theories of Bazin and Eisenstein, Metz and Deleuze, and between the cinemas of the classical era and those of Godard and Resnais, there exists a striking difference among arguments of how film subjectivity should be constructed, what it should resemble, how it should be organized and how the process of its constitution engenders the text’s fundamental relationship to meaning, message, and logic. In the last chapter I extended this study of film connotation and subject-object relations to the construction of a diegetic subject-function, which I hope to expound upon here through an analysis of what I call the code of subjectivity, to be complemented in the next chapter with a study of Godard and the code of objectivity.

Schwab continues: “the subject is the place where a certain differentiatedness achieves the status of self-feeling and projects a world picture.”2 The connection here between differentiation and a world picture is important, as it indicates how central the classical subject-object binary is to the manufacturing of philosophy, morality, and ideology. The process of organization through which the individual subject-position is differentiated from—and reconciled to—the objective pole of representation has been considered a basic premise of film representation, as is firmly indicated by Münsterberg’s quote at the head of this chapter. Arguing alongside suture theorists, yet not going so far as to place my inquiry in a specific ideological context, I am interested here in the connotative structure through which human subjectivity is simulated and how this renders cinema capable of performing a philosophical function. One way to analyze this, as I have done thus far, is to look at examples where it is decodified. In the opening chapters of this book I looked at the transcendental subject, or subjectivity in the position of the apparatus itself, to which I will return in chapter 5. And, in the previous chapter, I attempted to extend this to the diegetic subject, which led me to assess modes of film in which characters themselves are linked to the distribution of the sensible in the moving sound-image; these modes, such as the flashback, are what I call subjective modes of representation or elements of the code of subjectivity.

With Hiroshima, mon amour and Last Year at Marienbad we found that the construction of diegetic subjectivity is often dependent on the audiovisual coding of the relationship between past and present. This brings time, temporality, and narrative chronology—all of which, I will argue more fully here, are problems of the form of denotation—into the framework of subject-object relations. Stephen Heath asks rhetorically: “What is a film, in fact, but an elaborate time-machine, a tangle of memories and times successfully rewound in the narrative as the order of the continuous time of the film?”3 Heath’s question provokes me once again to wonder what film is, essentially, other than a temporal organization of events, narration. In response to Heath’s question I would say: everything. This ordering, or reordering, of time is only a problem of narrative structure and sequencing and is not always “successful,” nor does such an understanding consider the fluctuations between different image-types from which such a juxtaposition of moments (or “tangle”) might be built. Heath’s question is particularly interesting at this point in my study because it could summarize the general consensus concerning the work of Alain Resnais. Indeed, I can locate here the root of a problem that has led most critics to view Resnais’s work primarily as a reflection, through montage, on the nature of time. But aren’t Resnais’s systematic experiments with sound and image, and his unconventional structuring of temporality, only parts of a larger connotative project? Is Resnais interested in the nature of time or our relationship to it, to each other, and to ourselves?

Let me clarify, rekindling my reading of Deleuze from chapter 2: editing, or the assemblage of images and shots, is not essentially narrative. It is, first and foremost, formal, a means for organizing the immanent field, a relationality of different compositions of subject-object relations. In certain types of representation this juxtaposition produces a harmonious alignment of subject-functions; in others, as with Last Year at Marienbad, it produces a constant conflict or feedback of agencies, a contradiction of points of view. Because of the centrality of editing to Resnais’s works, critics from Raymond Bellour to Emma Wilson have drawn comparisons between him and Eisenstein.4 No two filmmakers, however, could have more dissimilar philosophical functions for editing. Whereas Eisenstein uses montage as a means for guaranteeing the spectator’s interpretation of a film, for producing specific meaning through the signification of a monolithic transcendental subject, Resnais’s use of montage offers a completely different connotative meaning. Contrary to Eisenstein’s precise and certain worldview, Resnais’s films aim for uncertainty, a polyvalent signified produced through a dialogic system of reference, leaving the image in a state of ambiguity and the spectator in a position of critical awareness.

And, while Resnais’s films are clearly concerned with problems of temporality and memory, these are secondary functions, much like the problem of time is secondary for Bergson’s Matter and Memory—secondary to, and instrumental in, reformulating the problem of the division between interior and exterior and the notion of subjectivity on which this division is based. Many theorists have reduced these interweaving interests of time and subjectivity to a representation of thought itself. I would argue, however, against the reduction of Resnais’s work to a metaphor that in most cases does not include thorough explanation, much as we saw in chapter 1, with allegories of perception concerning the works of Godard. Instead, I will reformulate this metaphor as a question of subject-object relations, and of the codification of subjectivity in cinema. To this end Wilson writes: “Resnais is fascinated by mental or subjective images, the virtual reality which makes up individual consciousness and is itself composed of both what we have known and what we have imagined. This interest in the finest workings of the mind … calls for an extraordinary reshaping of cinema and rethinking of the capacity of film to show us reality as it is imagined, as well as lived.”5

The crucial phrase here: “as it is imagined, as well as lived.” In other words Resnais is concerned with the connection between our subjective experience and our coexistence as an object, our being in the world. This dualistic nature of human subjectivity, phrased here in very Merleau-Pontian phenomenological terms, also reflects Deleuze’s understanding of the image both as the representative of something and as something in and of itself. While Wilson uses this aspect of Resnais’s work to address the visceral in his films, I will focus more on how this problem may permit us to investigate the cinematic construction of new circuits of thinking in which subjective and objective poles are displaced, confused, exchanged. In previous chapters we saw that image-types are conventionally combined not only to provide a sense of narrative logic or temporal cohesion but, more fundamentally, to construct a stable system of reference for the overall text. Be it in the relationship between depth and framing, between a shot and editing, or in the speech-image codification known as the voice-over flashback, the sound-image’s meaning varies according to the alignment of its significations with the source of enunciation.

In the previous chapter I introduced Resnais’s work as a deconstruction of the division between these objective and subjective poles, showing that in the immanent field the human subject is never fully isolated from its objective and intersubjective context. Keeping these problems in the forefront of this study, and drawing on a broader analysis of Resnais’s work during this period, I will now extend my conclusions from the previous chapter to what I call the code of subjectivity, part of a study of metacodes in which this and the next chapter function as a complementary pair. The code of subjectivity is a network of formal codes and signifying practices that merges processes of identification with those of subjective imagery to create a bond between the spectator, apparatus, and a character. The character and immanent field are linked both externally (we watch the diegesis as a function of the character’s actions) and internally (we watch the diegesis through the character’s eyes), bridging the emotional gap, as Alex Neill might put it, between sympathy and empathy.6

This code, however, has also been deformed in certain modernist cinemas as a means for subverting its connotations of certainty, such as one finds in Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) or Akira Kurosawa’s Rashomon (1950), films that provide multiple viewpoints of the same action or story and act as prototypes for recent developments in Hollywood genre cinema (see Pete Travis’s 2008 action thriller, Vantage Point, for example). This subversive tendency is particularly resonant in the work of Resnais, who was influenced by—and collaborated with—writers from the nouveau roman or “New Novel” movement, who were engaged with codifying a new type of psychological realism in literature.7 In reference to the relationship between Resnais’s stylistic innovations and the problem of cinematic realism, René Prédal describes Resnais’s work in terms that combine my philosophical argument with more conventional terminology of representational analysis, claiming that “through the will to present all facts on a level field,” Resnais produces “a total realism that situates itself beyond the tradition of cinematic realism.”8 To the extent that I will engage with the problem of realism, suffice it to say that Resnais’s films subvert the connotative foundations of conventional cinematic realism, shattering the denotative consistency necessary for a traditional model of verisimilitude. This rejection of stable denotation manifests itself in terms of two definitive extensions: the system of reference through which it is realized, as well the narrative clarity it helps to guarantee.

Resnais deconstructs the code of subjectivity to represent a mental world in which there is no dominant subject-function and, consequently, no clear causal narrative logic. In more Bergsonian philosophical terms Resnais’s code of subjectivity produces a subject that does not adhere to the division between interior and exterior. This deconstruction is based heavily on the recurrence of certain formal interactions, including alterations to the speech-image code, camera movement, and the constant interruption of denotation by varying types of insert sequence. Revealing the code of subjectivity to be based on conventionalized forms, it could be argued that Resnais liberates the image from the anchor of denotation. He draws our attention to the immanent field, wherein a multiplicity of subject-functions meet. His films therefore permit the spectator to assess the text critically and even to learn from it new paths of thinking—or in Jean-Albert Bron’s words, “to validate or eventually to modify her consciousness of the real, and through a ricochet effect to validate or invalidate the film in terms of its representation of the real.”9 Through this reflexivity Resnais provokes the spectator into a position outside of the typical comfort zone provided by the secreted transparency of mainstream cinema; as he himself once stated, in very Barthesian terms, Resnais wants to address the spectator in a critical state: “for that, I must make films that are not natural.”10

As I have pointed out, this formal challenge to cinematic convention can be seen quite clearly to reverberate on the level of denotation. Resnais (and Godard, as I will explore in the next chapter) produces a two-tier frustration of what David Bordwell describes as classical cinema, wherein “cause-effect logic and narrative parallelism generate a narrative which projects its action through psychologically-defined, goal oriented characters.”11 Beyond the mere breakdown of narrative causality and clear character motivation, however, one finds with Resnais a systematic rejection of the myth of the absolute subject and its foundation in the sensory monism provided by conventional formal relations. Resnais’s films are particularly telling in this regard because they focus on the problem of representation: spoken representation as communication between two people and, also, cultural representation as a discourse on history and the present. Resnais’s texts thus pose a diegetic problem for his characters, as well as an extratextual problem for the image, and the two are frequently merged as mental images to cast the characters’ internal projection onto the screen.

THE CODE OF SUBJECTIVITY

The code of subjectivity, as I have mentioned, is a set of signifying practices that provides for the structuring of subjective images that can be transposed from a character to the image and, thus, to the spectator. I will outline this metacode as playing two roles: (1) using formal tools specific to film signification, it molds its objective images to imply a privileged identification between the apparatus and a particular character; and (2) it provides for the transfer of this character’s experience to the spectator by aligning the film with that subject. In short, the code of subjectivity binds the spectator to the diegetic character by implying an affinity between the immanent field and that particular person. Furthermore, the code of subjectivity acts to transfer the character’s signifying processes onto that of the formal apparatus itself.

This code operates in numerous ways and has many possible contributing elements. For example, most conventional cinema has embraced this code on the purely quantitative level of narrative focus, considering a story through its influence on—and reaction to—a particular character, the hero or protagonist. Through the concentration of screen time placed on this character, and the character’s centrality in the causal logic of the events, he or she becomes the primary source for spectatorial identification.12 This mode of identification is reinforced by formal links organized between the diegetic subject and the form, such as with a following shot in which the camera follows a character as he or she walks, thus implying a direct link between the change in the image and that character’s trajectory. Kaja Silverman explains this as being an indexical signifier, in which the form itself seems to be attached by extension to its object.13 The character carries a privileged position in the immanent field, both in terms of physical presence and importance. Mitry refers to this as a semisubjective image, or “associated image,” an image in which the visual elements are constructed in order to give one character a bias in the representation.14 The objective pole of the recording machine is affected, we might say, by the subjective pole of the diegetic character. In addition to the moving camera, this code includes conventions of framing, in which one character is spatially dominant, bigger, or in a position of prominence in the composition, as if the character is given a place in the spatial organization that indicates his or her uniqueness from the rest of the space, that indicates his or her differentiatedness.

Sometimes the subjective interior of a character spills over into the objective markers of the image, such as when the plastic attributes are altered to represent the psychological state of the character or diegetic world. This is the case in Bazin’s aforementioned analysis of bourgeois mediocrity in Voyage to Italy and is also the governing principle of neorealism’s stylistic opposite, German expressionism. In the 1920s German cinema of Lang, Murnau, and Weine, the visual world of extreme plastic exaggeration helps to produce an overall mood that, in turn, connotes a motivated relationship between the immanent formal field and the characters within it. Taking this one step further, formal functions such as framing and movement often act to ease the transition from the objective image into a subjective image, in which the image-type aligns the apparatus with the character’s subject-position. An exemplary case would be the point-of-view tracking shot, in which the camera assumes the position of a moving character. As I have argued is the case in Vivre sa vie and Hiroshima, mon amour, the diegetic subjectivity of the shot is enhanced by using a moving camera that is looked directly into by the people it passes. The camera is signified to be the character, and the viewer is in turn signified to be the camera, thus allowing for a clean and unfettered passage of meanings and worldviews.

Other elements of the code of subjectivity are editing based, such as examples of suture wherein codes of editing create a subject-function that binds the image to a filmic position. This can include a speaking subject, as I analyzed in the last chapter, or a looking subject. The eye-line match, for example, cuts from a character in the act of looking. This cut sutures the point of reference into the perceptual act of the person looking and signifies the next image as the subjective gaze of that person. This is what François Jost calls “internal ocularization”: the camera has made the character’s gaze its own and, consequently, our own.15 Another term for this, though with only a slight alteration (the addition of a third shot, returning to the viewing character), is the point-of-view shot; the point-of-view shot is an example of what Mitry calls the “analytic image,” in which the camera views things from the diegetic character’s place, “identifies itself with her gaze.”16 The immanent field’s organization is justified, in this case, as the visual operation of the character. This transfer from the camera to the diegetic character produces an alignment between what is happening and how it is being shown, as is explained in Heath’s slightly more complex description: “The look, that is, joins form of expression—the composition of the images and their disposition in relation to one another—and form of content—the definition of the action of the film in the movement of looks, exchanges, objects seen, and so on. Point of view develops on the basis of this joining operation of the look, the camera taking the position of a character in order to show the spectator what he or she sees.”17

Because of this dualistic nature or purpose of its operational function, the point-of-view shot has been analyzed in many ways. For Dayan and Baudry, whose approach is concerned primarily with the ideological role of connotation, it is the extension of a bourgeois value system and artistic tradition. William Rothman and other Anglo-American writers, as I mentioned in chapter 2, see this convention rather as a rhetorical filmic device, narrative in its nature but incapable of being fully classified as ideological.18 Supporting Rothman’s position with a detailed textual investigation, Edward Branigan’s “The Point-of-View Shot” offers a thorough analysis of this practice as a strictly functional narrative device.19

Similarly, Heath points out that the point-of-view shot is only subjective to the point that it assumes the spatial position of a character. For Heath there is no great difference between subjective point-of-view shots and objective non-point-of-view shots, merely an “overlaying of first and third person modes.”20 Such a code does not for Heath necessarily assume anything beyond that, such as the character’s psychological experience. This observation provides me with an interesting point regarding the code of subjectivity as it is used classically: it does not necessarily change the image qualitatively. Mitry reiterates this: “A completely subjective cinema (on the visual level) is nothing other than that which ‘objectively’ relates the vision of someone who is effaced behind that which she presents to us.”21

Mitry points out, in terms that conjure the analyses of Baudry and Dayan, that this perpetuation of the subjective representation’s objective characteristics effaces the character at its source—at least this is the implication, an implication nearly always reinforced in mainstream practices. This effacement, frustrated on numerous levels in the works of Resnais and Godard, is itself an effect of the organization of the immanent field. While there may be no noticeable difference between the two types of representation, there is a subtle difference in their systems of reference, which is of utmost interest to this book. Though Heath may have a point, the film is still being systematically altered, as Deleuze might say, according to the image’s origin. Moreover, I have found that the qualitative similarity is not maintained, for example, when the shot is taken out of a linear context or when stripped of conventional codifications of sound and image.

In other words, I would argue that, though Heath is accurate that the point-of-view shot does not always indicate an aspect of the character’s subjective transformation of what is being viewed, this effect does play a role in affirming or challenging a text’s connotations as a function of its system of reference. While the form of content may not be altered, the system of differentiation upon which the denotation is based assumes a particular dynamic. Nick Browne attempts, in “The Spectator-in-the-Text: The Rhetoric of Stagecoach,” to understand another possible effect of this alignment, which is the identification with a character through the eyes of another character—that is, the unrolling of images through which our process of identification differs from the position in which we view, or how the point-of-view shot can provide contradictory systems of reference.22 This helps me to iterate a duality with which the code of subjectivity is infused: within the subjective there always remains the objective pole as well.

While the structuralist mode of analysis employed by Dayan and others may differ from the rhetorical narrative analysis proposed by Branigan and Browne, one can locate a fundamental similarity in their attempt to understand the point-of-view shot as an organization of images via a fluctuation in the images’ implied source. That is, the self-imposed polarity of their approaches can be reconciled through the framework of film as an organization of subject-object relations. But can the point-of-view shot be the only type of subjective image, the only level of diegetic subjectivity in cinema? Of course not: there are many degrees of the subjective image, as Mitry elaborates to great extent.23 There are also internalized subjective shots in which the image assumes the imaginary realm of the character—the dream sequence, for example. We see a character sleeping, followed by a sequence of shots; the transition between an objective representation of the sleeping character and a subjective representation of that character’s imaginary is usually indicated by some sort of audiovisual effect, such as a wavering image or the plucked notes of a harp. This effect signifies that what follows is a dream sequence. These formal tools serve a connotative role: the immanent field shifts its origin of meaning onto the subject-position of the diegetic character. Such editing-based conventions of the code of subjectivity become more complicated when another sensory plane of expression is added, as seen in the previous chapter. The voice-over flashback merges the narrated and the narrating: the subjective mode and the objective mode are linked by the bridge of a codification of speech. In most classical practices this subjective past slides seamlessly into the objective past by shifting the plane of verbal signification from the voice-over to that of diegetic conversation. This aligns the subjective with the objective by granting both the enunciating character and the transcendental subject a certain relationship with the image. They are interchangeable, linked through their inextricability from the immanent field, their relationship with the formal base.

In the films of Resnais, however, such constructs are wafer thin. Resnais’s work is particularly useful here because it incorporates a variety of devices that make up the code of subjectivity. For, whereas Godard attempts to describe a subject’s interior by contextualizing its objective exterior, Resnais tries to turn a character inside out: “he begins with the interior of the character and moves toward the exterior.”24

ALAIN RESNAIS AND THE CODE OF SUBJECTIVITY

It is through the use and deconstruction of the code of subjectivity that Resnais explores his most regular themes of the human condition: the relationship between the past, present, and future, and the inherent struggle between the real and the possible, between personal imagination and collective reality. Evoking an opinion common to all writing on Resnais, James Monaco describes these films as attempting to deal “with the way we comprehend the world.”25 But what does this mean, and how might we understand this in more concrete terms? Resnais’s work should be framed not according to the representation of consciousness, or some such metaphor, but according to its philosophical organization of subject-object relations in a cinematic deconstruction of the division between interior and exterior.

I agree with skeptics of formalism that Resnais’s stylistic endeavors would be of less interest if they were not used to engage historical problems and the social and moral issues that arise alongside them. But they do, and that is why so many people find his work moving, important—“philosophical” in a conventional use of the word, meaning how movies can make us think about deep stuff. Directing this reflection toward contemporary geopolitical problems, as well as questions of how culture constructs history out of such problems, Resnais’s films between 1959 and 1968 are uniquely engaged with history as a process of representation, combining international events with the problem of recording, representing, and preserving history between individuals (such as Nevers and Hiroshima, X and A). I say “uniquely engaged” because Resnais’s vigilant consideration of contemporary historical events (the Holocaust, nuclear warfare, the colonial war in Algeria, the Spanish Civil War) is unique to this period of his work, after which his cinema becomes more theatrical, less topical, and his dedication to films with a sincere conscience places him among a minority in film history generally.

Resnais’s films from this period manifest a recurring conception of history and memory as being interrelated in some form of linguistically paralyzed sublime, in which the ability to name or to conjure images through words is constantly frustrated. As such, there is an overriding uncertainty in his signifying systems, an ambiguity and a polyvalence that refuses the straightforward production of denotation (which often frustrates viewers seeking an easily decipherable storyline). But, again, let us demand: how is this achieved? It may help to begin with Resnais’s arrangements of speech and image, as introduced in the previous chapter. In most cases Resnais uses the voice-over flashback to construct a subject-function through the representation of memory, in which the coexistence between past and present provides a coherence of representation that is posited as an enunciation from a position of subjective unity. This ranges from the unilateral narrating subject to the Bakhtinian communication process in which a subject constructs itself in constant reference to an implied other, a range of possibilities introduced in my analysis of Hiroshima, mon amour and that I will extend in this chapter’s analysis of The War Is Over.

Resnais’s work does not always focus on the voice-over; however, it does rely to a large degree on other experiments with editing. Alternative examples I touched on in chapter 3 include the coexistence of two parallel stories, such as one finds in Muriel. This film uses the juxtaposition of images to show the remnants of the past in the present of a particular character, not in terms of an allegory but in terms of the juxtaposition of image-types. A similar premise is provided via the narrative foil of a time machine in I Love You, I Love You, which revolves around a man’s attempt to come to terms with his wife’s untimely death. The last film Resnais made before his five-year absence from commercial filmmaking, I Love You, I Love You is often considered his text par excellence because of its frenetic experiments in montage and temporal order, which could be analyzed as a constant deformation of the conventional organization of subject-object relations.26 Robert Benayoun calls I Love You, I Love You “an editor’s sinecure: a film where montage becomes a philosophical tool, a dialectical manipulation of the most fundamental degree.”27 The focus herein on the importance of editing belies the influence, discussed by Resnais himself, of Marcel Carné’s innovations with narrative editing. In films such as Daybreak (1939), Carné alters the conventional temporalization of the story in order to produce what Resnais calls “moments of uncertainty,”28 a rejection of denotative stability that would be infused throughout Resnais’s organization of subject-object relations.

Carné’s model of what is better known as “poetic realism” offered one of the first systematic attempts to reorder classical narration according to a particular character’s point of view. Resnais takes this tradition of narrative editing one step further. Beyond merely frustrating the narrative, he uses editing to challenge the unilateral and absolute vision of any one individual, a tendency that aligns him with other modernist filmmakers such as Luis Buñuel.29 Resnais, however, must first encode a subject in order to deconstruct it, which he does through traditional means of the code of subjectivity. Aside from such experiments in temporal narration, Resnais’s thematic visual style is perhaps best known for its epic use of the tracking shot, so prominently placed in Resnais’s connotative order that it inspired Godard, in talking about Hiroshima, mon amour, to comment: “tracking shots are a moral issue.”30 This formal tool is central to Resnais’s earlier documentary work, such as Night and Fog (1955) and All the Memory in the World (1956), and continues into his early fiction films. Resnais’s tracking shots, almost always moving forward, provide a physical sensation of pressing through the world. The tracking shot, as we saw in Hiroshima, mon amour, is a marker for the subjective nature of memory; only, Resnais uses it to construct a subject-function that he can subsequently divide.

As in Last Year at Marienbad, the tracking shot does not imply an unlimited movement or transcendental omnipresence, as Baudry argues in his theorization of the transcendental subject,31 but quite the opposite: through its relation to framing, montage, and sound, the tracking shot reveals the limiting aspect of the frame—it insists on the partiality of the image, the lack of a specific subject-position to associate with the visual. Moreover, Resnais’s tracking shot usually follows no narrative motivation: as Alain Fleischer puts it, “The camera seems to displace itself for nothing, dispossessed of drama.”32 Somewhat similar to the Vertovian system of montage that I argued for in my analysis of Two or Three Things I Know About Her, Resnais’s tracking shot removes the camera’s perspective from a fixed spot and transfers subjectivity into a public space: it is a “subjective tracking shot without [a] gazing subject.”33

It is not, however, fully objective either. Roy Armes tends toward familiar rhetoric when he describes Resnais’s tracking shot as “an attempt, still very crude and primitive, to approach the complexity of thought, its mechanism.”34 Again, I believe it would help to convert such metaphors to a formulation regarding the immanent field as a space for the organization of subject-object relations. One could argue that, at the very least, the tracking shot attempts to represent thought as a function of the subject’s differentiation from or relationality to the visual content: “the possessing of space by an organ of viewing.”35 In a way, then, it is an extension of the transcendental subject, implicating the camera as a mobile viewing subject, passing through a world of objects. Prédal takes this further to suggest that the forward tracking shot of Last Year at Marienbad is, in fact, a type of violation of the object, or what he calls “cinematic rape by forward-tracking.”36 Yet there is never any specific clarity in Resnais’s films to whom the image belongs, for whom it is an extension. The tracking shot adds an element of ambiguity to the position of enunciation: the frame is stable yet fluid, consistently proportionate yet always moving.

Moreover, the moving camera posits the impression of omniscience, but this is nullified by a form of editing that decenters any single system of reference. Though his editing techniques have often been categorized as primarily concerned with memory, Resnais has argued against this, making a decisive division between the notion of memory and one that he finds more fitting: the notion of the imaginary.37 While “the imaginary” has served as the grounds for many psychoanalytic studies of film, I prefer to consider it more as a mechanism that permits us to consider not the Lacanian process of human subject-formation but the construction of filmic subject-functions. As we saw with Mitry’s categories of subjective imagery, there is no representation more fully subjective than the mental image. The mental image is no longer, like the point-of-view shot, an objective image seen from the standpoint of a character. The mental image is an entirely different regime of representation. An experiment at the center of Resnais’s films during this period, the mental image sequence is frequently intertemporal, either a flashback or flash-forward—a structure of the imaginary in which the referential system of a diegetic subject-position allows for a shift in diegetic time. “Is this not the foundation of a unified subject?” one might ask. But—as with the tracking shot—what would otherwise be a conventionally coded adjustment of temporal context becomes, for Resnais, a realm of incertitude, doubt, and ambiguity.38 The sequences do not isolate a subject-function from the surrounding world, as with traditional forms of the code of subjectivity, but, instead, illustrate how the individual attempts to build a bridge between the inside and the outside.

What is shown in these sequences cannot necessarily be considered “memory” or “foreshadowing,” since its denotative certainty is often nullified. The classical construction of the mental image—that is, implying that what we are seeing is, in fact, the character’s representation of an experience—necessitates, as I demonstrated in the last chapter, certain configurations of speech and image, certain organizations of subject-object relations. With the voice-over flashback, such as in the opening sequences of Hiroshima, mon amour, speech often rests momentarily objective, in the present, thus permitting the visual image to deviate. The representation of memory as a structure of the immanent field, therefore, rests on a division between elements that can become highly problematic. In such subversive forms, Monaco argues, “Resnais is doing nothing less than asking us to give up preconceptions of causality and the flow of time”39—causality and time, I would argue, as forms of denotation, the structure of which is justified by a specific system of reference. Resnais is asking us, ultimately, to abandon our conventional understanding of causality and time as they are organized through subject-object relations. Deconstructing the monistic unity of the subject of memory, Resnais connotes that history and memory are not purely internalized phenomena, are not phenomena impervious to intertemporal and intersubjective influences.

In a particularly unique twist, Resnais also extends the intertemporality of the diegetic subject through the use of the flash-forward, which seems to have gone neglected in the majority of analyses of his oeuvre.40 Whereas the flashback offers a character’s representation of what has happened, the flash-forward presents us with a character’s projection of future possibilities, a person’s anticipation of the exterior realization of feelings or judgments that are, as yet, only interior, thus further decentering the present as a stable praxis for denotation. This second-take effect—be it in flashback or in flash-forward—provides a sort of repetition and transfiguration on repetition that is central to Resnais’s deconstruction of the code of subjectivity. I would be inclined to disagree here with Wilson’s suggestion that Resnais’s films “move in repeating circles”41—after all, even the constant return to the past in Muriel, the familiar hypnotic wanderings of Last Year at Marienbad, and the multiple recurrences of the same memory in I Love You, I Love You spiral out of their own bases of repetition. There is always a slight difference, a slight alteration added to the organization of subject-object relations.

Other permutations of this experiment with repetition and difference include the representation of a character’s imagination. In The War Is Over, for example, Resnais presents us with Diego’s (the hero, played by Yves Montand) mental image of a young woman he does not know. Diego’s imaginary unfolds in the form of a visual sequence that begins with a young woman, walking down the sidewalk in front of the moving camera, which follows her (fig. 4.1); this cuts to another shot, constructed with the same scale, composition, and camera movement, in the same setting and blocking, but of another woman (fig. 4.2); in subsequent shots she is replaced by another young woman, multiple times, the collective group of which follow through with the motion of walking down the sidewalk and entering a bar.

These different women are manifestations of Diego’s imaginary version of Nadine Sallanches (who turns out to be played by Geneviève Bujold). In this case the rapid succession of images represents how the unknown object, in its multiplicity of possibilities, can nonetheless be conjectured in the imaginary, even mastered to a degree by the coherence provided through continuities within the images’ organization of subject-object relations. As Bordwell points out, “Similarity balances difference: graphically matched compositions and figure/camera movements play against the fact that each young woman is unique.”42 The formal continuity manages to contain the shifts in content, a continuity that extends further than just the visual design.

Bordwell also points out that we understand this to be Diego’s subjective imaginary and not some objective image because of the continuity of the soundtrack. The soundtrack continues with the conversation that led into this insert sequence. Much as in Hiroshima, mon amour, the fracture between two formal elements provides for an overlapping between the objective (Diego’s ongoing conversation, Nevers’s verbal recollection) and the subjective (Diego’s mental images of women, Nevers’s mental images of France). And so we are lured into the illusion of a codified subject-function, prompting Youssef Ishaghpour to write: “Resnais conceives of the cinema not as an instrument of representation of reality, but as the best means for approaching the psychic function.”43 But are such constructions of subject-object relations connoting the “thought” process of an enclosed and unified subject, or the open collectivity of memory as a cinematic convention—that is to say, is Resnais attempting to simulate thought as we have conventionalized it, rationalized it, or is he using film form to conduct experiments in cinematic thinking?

Another example of an operation based on repetition and difference is the repetition of verbal descriptions, but accompanied by different images, such as we saw in Last Year at Marienbad. This represents the exchange of a thought or mental image from one mind to another, or perhaps more precisely the mutual construction of representation, much like Bakhtin’s notion of the dialogic, but extended further than in Pasolini’s example of free indirect discourse. With Resnais we have something akin to Kurosawa’s Rashomon or Welles’s Citizen Kane, which offer constant variations on the same referential content, in which the subjective and objective lose their conventional boundaries.

By fracturing the system of reference beyond the alignment of the objective and subjective, such films pull into the spotlight the very mode by which the artificial unity of an enunciating subject-function is required for narrative clarity. Like these other films, Resnais’s work unravels the coded unity of a single subject-function in order to represent memory as something shared, collective, built from multiple perspectives. To expand a citation from Deleuze noted in the previous chapter’s analysis of Last Year at Marienbad: “He discovers the paradox of memory as shared by two, by several … characters as completely different non-communicant sites that compose one global memory.”44 This “global memory”—which is articulated in a different cinematic way in Godard’s Contempt—does not belong to a character only but binds characters through an immanent field constructed to include multiple subject-functions. This is the very premise of the mental image. Jean-Marie Schaeffer writes: “The manner in which beings relate themselves to reality: we gather knowledge about reality through ‘mental representations,’ induced by perceptual experiences but also by the internalization of innumerable social understandings already elaborated in the form of symbolic representations that are accessible to the public.”45 Schaeffer makes a crucial link here between perception, the mental image, and how each of these is conditioned by sociocultural codes of representation. The cinematic code of subjectivity is itself a “publicly accessible form of representation,” a code that has been forged through a century of cinema’s presence in our imaginary.

The subject, as Schwab points out, may very well be a cosmic normality, a natural condition of organizing the world, and it is inevitably signified through any process of representation. But the cinematic production of this differentiation, this book holds, is a codification based on certain organizations of the immanent field of formal relations, which operate to provide a rigidity that anchors this differentiation within a larger order of meaning that can, if desired, be unhinged, overturned. Resnais’s films illustrate this argument through a constant subversion of conventional subjective forms, caused by slight alterations to the alignment of elements that make up these codes. I hope now to illustrate this further through an analysis of an often underappreciated jewel of Resnais’s early period, The War Is Over.

THE WAR IS OVER AND THE CINEMATIC (DE)CONSTRUCTION OF THE CARTESIAN SUBJECT

Released in 1966, The War Is Over looks at a topic particularly tied to a person’s being in the world: political action. Here, Resnais’s dominant themes—uncertainty, temporal instability, history and the individual—resurface in a specific context: leftist activism in Western Europe in the 1960s. Of all of Resnais’s films during this period, The War Is Over contains the most expansive variety of formal experimentations with filmic subjectivity, anchoring these experiments to a specific sociopolitical problem that was being debated widely among French intellectuals and artists of the 1960s, who had become firmly entrenched in the workers’ and student movement. As such, the film was seen as a major step for Resnais, integrating his experimental formalism into a concrete and topical story that, for all intents and purposes, actually has a legible plot—prompting Cahiers du cinéma reviewer Michel Caen to write in his review: “Things have changed with Alain Resnais.”46

Widely considered upon its release to be Resnais’s most well-rounded film,47 The War Is Over has, perhaps for this very reason, escaped the type of in-depth analysis afforded to many of his films from this era. Despite a number of intertemporal fluctuations, Ronald Bogue points out that with this film “one might suppose (as many critics do) that Resnais creates a present tense narrative.”48 Like Last Year at Marienbad, however, this film takes place in the present only inasmuch as the present is a meeting point for past and future trajectories of representation, a universal present. In this analysis I will focus on the unfolding of these temporal trajectories in conjunction with the construction and deconstruction of cinematic subject-functions. In Narration in the Fiction Film Bordwell offers a thorough analysis of the film’s narrative devices in a section titled “The Game of Form.”49 Bordwell points out continuously that this film, a prototype for what he calls “art-cinema narration,” produces ambiguous image-types while at the same time “defining the range of permissible constructions.”50 Though Bordwell claims in the same passage that this film “appeals to conventional structures and cues while at the same time introducing significant innovations,” he goes on to situate these innovations as a function of denotative encoding. For Bordwell, that the narrative devices and formal experiments are justified through an alternate code of subjectivity makes the film explicable along classical narrative lines. I will argue, however, that this take on the film ignores the connotative significance of how the narration is built in relation to the organization of subject-object relations.

The War Is Over revolves around the character of Diego, a Spanish exile orchestrating Spain’s communist movement from Paris. Having fought in the civil war during the 1930s, he fled and continued the fight in France, where he is now reaching a moment of existential crisis: he has dedicated his life to a cause that seems to be mired in the past and, at the same time, to have outgrown him. After decades of devotion to the cause, he finds that his comrades no longer view him as ideologically sound, while the new generation of activists is too radical for him. The setting is one of political party operations, but this is not a film about politics; it is about one individual’s attempt to reconcile his internal perspective with his external context. In Wilson’s words: “Rather than offer lessons on militancy, Resnais offers insight into the doubts, hesitation and commitment of an individual.”51

As a collection of image-types, The War Is Over revolves around Diego’s attempt to transform his own beliefs into an external reality. It is thus apt that Prédal titles his Positif review of The War Is Over “From Reflection to Action,”52 for the film is just that: a ninety-minute movement from reflection to action, a text through which the barrier between interior and exterior is torn down. As such, this film is about much more than one man’s struggle within the communist movement: it is about every person’s quotidian struggle to exist in society, hovering between thoughts and beliefs on the inside and actions and events on the outside. In many ways I am tempted to call this film Two or Three Things I Know About Diego! Just as in the Godard film from the same year, Diego’s plight is removed from the epic grandiosity of history books and modes of heroism and is grounded in the banality of everyday life. And, with it, so is the mental image grounded in a less fantastical context. “Imagination is not always fantastical,” said Resnais in an interview just after the film’s release: “most often, mental representations are rigorously banal, quotidian.”53

It is thus emblematic of Resnais’s films from this period, which bypass narrative action and historical explication, setting these mainstays of conventional cinema in the background of ordinary existence. This filmmaker’s most “radical” deviation from classical mainstream fiction cinema may actually be his desire to treat what he called “the imaginary side of the quotidian, the banal part of the imagination.”54 The banal aspect of subjectivity permits Resnais to redirect the film’s focus away from denotative content and toward the form itself. The film’s construction of subjectivity seems simple on the surface, but I will explore here how The War Is Over allows a vast web of intertemporal and intersubjective fractures in order to assert the main character’s dialogic relationship with the world around him.

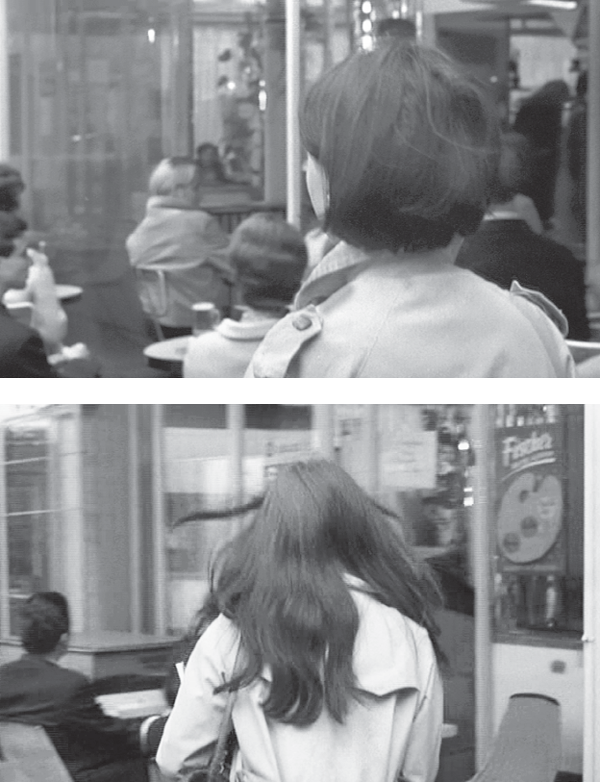

The conventional code of subjectivity is utilized in this film on numerous levels. First, identification with Diego is signified by the film’s narrative logic. The film’s action revolves around him, and his physical and mental representation occupies the majority of screen time. More important, though, the film’s formal devices are composed according to his motion and perspective, thus positing his agency not only on a narrative level but also through the suturing of formal codes. The use of framing and camera movement in this film is conventional, classical, respectful of the code of subjectivity. Diego is always placed either in the prominence of the frame (foreground and/or center) or filmed from behind. This latter detail constantly places the camera both facing in Diego’s spatial direction and, also, “behind him,” as if in a position of support, encoding the image with both identification and empathy (fig. 4.3).55

The dynamic between shot and montage is integral to this identification as well. In conversations, for example, the use of crosscutting juxtaposes close-up images of him with medium shots of the people he talks to, implying them as objects of his gaze, at a further distance both from him and from the viewer. Similarly, camera movement in this film is relatively moderate for Resnais’s oeuvre and, as Armes aptly notes, the moving camera is nearly always shot from Diego’s perspective.56 Even when it is not from his perspective, the camera’s movement is guided by Diego’s motion. This tracking shot, or following shot as I discussed earlier, is a conventional part of the code of subjectivity, a sign indexically (to use Silverman’s term) signifying the apparatus’s alignment with Diego’s character, often going so far as to then assume his point of view. This occurs numerous times when Diego is walking, for example: the camera will move with him, following, as if the apparatus itself were linked to his physical agency. It is then extended through an eye-line match: he looks in a certain direction, and the camera cuts to the object of his gaze. This is complemented by the direct address of other characters’ gaze into the camera, as if the camera, and through it the image itself, were organized from Diego’s perspective. Unlike in Two or Three Things I Know About Her, direct address is meant in this film to align the camera with a diegetic character, with Diego, not to reveal the transcendental subject as a construction.

Ultimately, there is nothing particularly radical about the mise-en-scène of this film; it lacks the ornate luster and mocking mirrors of most of Resnais’s visual extravaganzas. But the conventional illusion of narrative totality and the unilateral production of meaning are central to the film’s philosophical experiment. Diego’s is the subjective position signified by the text, yet his agency does not exist unilaterally. Quite the contrary, Resnais subverts the isolation and autonomous totality of the classical subject through the contextualization of Diego’s mental images, which capture particular moments and project possible others, breaking down temporal barriers and conflating the real and imaginary. They are his subjective representations, but his interior does not exist in a vacuum. The immanent field opens his subjectivity up to a range of other voices, other subjects and possibilities. As Prédal notes concerning this film: “imagination is not vagabond but attaches itself to concrete problems.”57 Even when Diego’s brain triggers fantasies, his skull resides in the physical world.

This tension between interior and exterior manifests itself in different ways. The opening scene of the film, for example, unfolds according to a dialectic flow between two voice-overs: one is Diego’s voice, and another belongs to an anonymous narrator who turns out to be the man sitting next to Diego during this scene. The images show the world from Diego’s perspective, introduced to us through what Bordwell calls visual “cues of subjectivity,” which include aforementioned codes such as the juxtaposition of a viewing subject with the object of his vision and the direct address of an interlocutor.58 The visual point of view established is connected through framing and editing to Diego’s perspective. This implies, through the basic assumption of sensory harmonization, that the voice-over is his as well; however, the voice-over addresses a particular “you” as it ruminates on Diego’s story. As Diego watches the scenery pass by, for example, the voice-over says: “You watch the scenery pass by.” This is a marked contrast to the more conventional, sensory-total subjective enunciation of “I watch the scenery pass by,” playing with language and agency much the way Last Year at Marienbad does and in direct conflict with the conventional “I saw” subjective enunciation in the opening scene of Hiroshima, mon amour. The sound-image is composed of two subject-functions, coexistent within the immanent field: Diego as visual and viewing subject, and someone else as aural subject.

Subjective twice over (not even counting the implicated subjectivities of the filmmakers, apparatus, and spectator), the film can still immediately become objective: the voice-over is revealed to be part of a dialogue between Diego and his driver. The voice-over becomes a diegetic conversation, which then leads into Diego’s own voice-over, maintained in the second person. For Wilson this use of “you” suggests a distance between Diego and his experience, a “self-consciousness” or “objectivity” as she calls it.59 In a way this speech-image composition renders him once-removed from his own experience. Narration becomes dialogue, and dialogue becomes a sort of internal exchange that connects the character to his past and future selves, thus entangling the system of reference within the polyvalent fracture of an intertemporalized “I.” In this momentary experiment in cinematic thinking, provided by Resnais’s dislodging of conventional sound-image codes and assaulting the very foundation of classical Cartesian subjectivity, we are led to the revelation that a Bergsonian world is also a Bakhtinian one. Roman Jakobson refers to this as the “intrapersonal” aspect of inner speech: “Inner speech … is a cardinal factor in the network of language and serves as one’s connection with the self’s past and future.”60

Even this is not fully the case, however, because this voice-over itself is never stable. That is to say, since each image consists of a struggle between objective and subjective poles, no one element can be considered fully “internal.” Bordwell rewords this as “the ‘subjectively objective’ voice in Diego’s own mind, a kind of internalized Other that ponders his actions in an impersonal way.”61 Indeed, this adds an aspect of reflexivity, in which Diego—or the viewing subject-function—is set apart from the aural source of signification. With this simple pronoun the code of subjectivity is reformulated. Moreover, as Bordwell points out, the voice-over is not wholly subjective, for it is often not even in Diego’s voice. “Is it then the voice of some ‘authorial’ narrator?” Bordwell demands. Or, in words that conjure both Münsterberg and Bakhtin, “is it a ‘subjective other,’ an impersonal objectification of his thoughts?”62 Bordwell remarks on the ambiguity of the spoken discourse, which constantly wavers between the narration of events and the uncertainty of whether those events took place, and concludes with seeming discomfort: “Self-conscious narrator, or unselfconscious character? The uncertainty is never dispelled.”63

Bordwell’s interrogation illuminates the Diego-as-subject construct on numerous levels. Not only is there an external world for him, full of people and causes and actions, but there is also a lack of unity to his interior experience, which includes both an intertemporal fragmentation and a polyphony of voices. This deconstruction of the division between subject and object is not limited to experiments in sound-image codification and narration but is part of the greater network by which the film uses, reveals, and transforms the code of subjectivity. This network consists mainly of different types of insert sequences that constantly alter the system of reference. These sequences vary from the psychologically abstract (an objective image altered to connote the psychology of the character) to the intertemporally subjective (a future image projected by the character). An example of the syntagmatic progression from the first type to the second is provided in duplicate: two scenes of lovemaking, one between Diego and Nadine (the daughter of one of his collaborators, and herself a member of the radical student group) and the other between Diego and his longtime partner, Marianne (Ingrid Thulin). These two scenes are stylistically coded to connote the effect of each respective experience on Diego—these are subjective in the way that expressionism and neorealism can be seen as subjective, extensions of the characters’ psyche to the totality of plastic representation.

The first scene is a surreal, ethereal fantasy: Nadine’s body parts are filmed in close-up against a white backdrop, like a naked angel floating in a beam of light (fig. 4.4). These images are strongly similar to the images of isolated female body parts found in numerous of Godard’s films (notably A Married Woman), though not in a self-conscious manner such as we find in Godard. While his films often grant agency to female characters, Resnais is not concerned with sexual politics. Much to the contrary, we see in these images a differentiation between the subject-function touching (Diego) and the object-function being touched (Nadine). In his review of the film Michel Caen evokes the stylistic sensuality of this scene, implicitly glorifying its classical objectification of the woman’s body: “Nadine offers herself to him. Nude, the light radiating from her sides, forcing us to rediscover black-and-white cinema … her thighs open and the screen quite simply delivers the image of physical love to us.”64

While the structuring of sexual difference in this sequence (and its analysis) merits criticism, it is of interest to this study for what Bordwell describes as a dichotomy of code, in which the representation “is both ‘reality’ (the couple did make love) and ‘fantasy’ (connotations of impossibly pure pleasure),” what I would argue to be overlapping objective and subjective image-types.65 Despite Nadine’s spatial dominance of the screen, there is a clear differentiation between subject and object. While they may share pleasure, their experience is not intersubjective; there is a differentiation constructed between them.

This scene is followed by a shot that is at first incomprehensible: a banister in an unidentified apartment building. We find soon thereafter, upon Diego’s arrival in this building, that this is the railing leading to Marianne’s apartment. But before discussing this editing technique, let me compare the previous scene (with Nadine) to the second such scene (with Marianne). The latter scene is different; the immanent field of formal relations manifests a different organization: intersubjective and carnal, framed in ways so that there is no sense of differentiation between the people involved. This no longer seems fully like Diego’s subjective expression but something more mutual, intersubjective. Whereas the scene with Nadine is an “essentially loveless, cerebral affair,” Armes notes, the one with Marianne is infused with “warmth and passion” of two “sensual bodies seeking each other.”66 Following the scene with Marianne is also a flash-forward, this one to the political meeting that Diego will attend the next day (fig. 4.5).

Each of these erotic insert sequences ends with a flash-forward, a new weapon in Resnais’s mental-image arsenal. As Bordwell points out, The War Is Over “creates a unique intrinsic norm” for the representation of diegetic subjectivity: instead of memory or fantasy, we are “to share the character’s anticipation of events.”67 The intertemporal instability of the mental image grows more extreme as the film goes on, as the forms of representation enfold more possible times, more possible agencies, more possible subject-object compositions into the dialogic structure of the immanent field. As the film progresses, Diego finds himself stuck between his duty and his conscience: he must alert his colleague, Juan, of an ambush waiting in Madrid, without compromising the larger cause. This mission becomes all the more complicated as other colleagues are arrested and even, possibly, killed; as his veteran peers denounce him for not having enough perspective on the greater cause of the movement; and, as the younger radicals rebuke him for the inefficiency of the traditional, strike-oriented and systematic—as opposed to violent—left.

Let me consider the multiple inserts involving Juan, who is allegedly being detained and tortured by the Spanish police. These inserts recur numerous times: once before the torture theoretically could have been going to happen, once as it is being considered a possibility because of the realization of a breach of confidence, and once when it has been determined as actual fact. It was once premonition, then speculation, and then what Bordwell calls “speculative flashback.”68 Another recurring insert-sequence is of the meeting with Diego’s peers in the Communist Party, at which Diego is suspended from activity for having a “subjective view of the situation.” This scene is represented multiple times as well: once while the anonymous voice-over prepares Diego for the near future, once after he has made love to Marianne, once as it actually happens in real time, and once while Diego is trying to decide what to do afterward. In both recurring insert-sequences the same scene is viewed as numerous types of mental image, each one accompanying a different mode of Diego’s internalization of events and each one possible to situate along a temporal plane. There is the hypothetical past, the certain virtual past, the hypothetical present, and the hypothetical future. The same basic sequence is interchangeable as fear, regret, concern, and anticipation.

Each of these could be understood essentially as a structure of subject-object relations. As Deleuze notes concerning these dynamic editing patterns, “the function with Resnais is not the simple usage of the object, it is the mental function or the level of thought that corresponds to it.”69 Deleuze offers here a variation on the typical analysis of Resnais’s films as representing the thought process: instead, as I have argued, we could see the film as a series of experiments in cinematic thinking, modes of relating the self to the world, organizations between subject and object. Resnais’s image-type is not necessarily an expression of thought, which would be impossible to qualify or to corroborate; it is, however, a particular construction of subject-object relations, and thus the condition for the representation of thought—what Deleuze might refer to as the “enunciable.” And, as these representations are laid out before the spectator, we are made privy to Diego’s attempt to digest the world external to him and to transform this digestion into a decision and, then, action. Bordwell claims that the result of such a “highly restricted and deeply subjective narration” is that, “as we learn the narration’s devices, we are inclined to trust Diego’s judgment.”70 It seems to me quite the opposite, however: as the forms of representation dissolve what we know as conventional narration, subjectivity as a concept is itself deconstructed, revealed as incomplete, fragmented, and prone to error. We are relieved of the implications of having to trust or believe a particular filmic subject, and our focus is directed, instead, toward the immanent field through which this subject is constructed, through which this “judgment” is manifested.

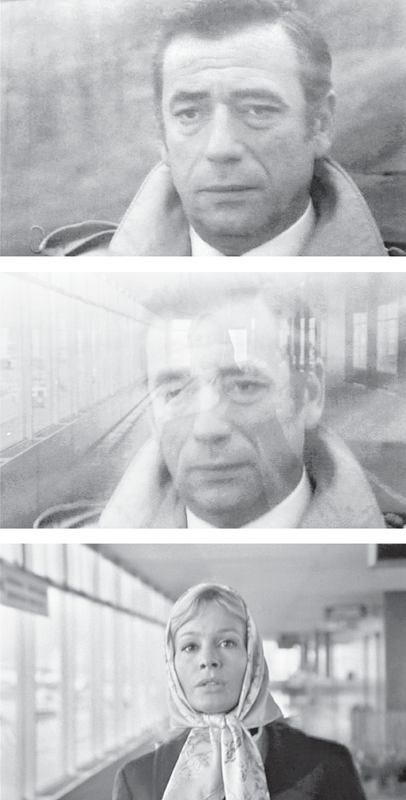

I would thus posit a causal relationship between the structure of the image, as an organization of subject-object relations, and the denotative stability of narration. This becomes all the more clear in the final scene of the film: the lack of closure with which the film concludes offers a finale to this rejection of narrative logic and the conventional divisions between subject and object on which it is predicated. Instead of proposing an image as an illusory act of natural perception, the film is structured to illustrate the nonlinear and a-chronological process by which the character posits himself as a subject in relation to the external world. It is not a unilateral act of perception but is instead the dialogical interaction with the world around him, offered to us as a function of the relations organized within the immanent field. Such a dialogical interaction is often highlighted through the use of dissolves between images of Diego and other characters, what could be viewed as a merging of two separate subject-functions. This is perhaps best illustrated by the final images of the film, which consist of a dissolve from a shot of Diego, who has left for Spain, to one of Marianne, who rushes through the airport on a mission to save him (figs. 4.6–4.8).

This formal overlapping of images accentuates the permeability of the individuals and reveals the illusionary premise on which the purely isolated subject-function is constructed. As Bordwell points out: “The very last shots identify Marianne and Diego, making her our new (and limited) protagonist; she now obtains, perhaps, a depth of subjectivity commensurate with that earlier assigned to Diego.”71 Here is a perfect example of how Resnais refuses to use the code of subjectivity to isolate a particular character. What is both unique and radical about Resnais is that the code of subjectivity is always used, instead, to subvert the notion of a fully independent subject, to show the subject as only one of many overlapping and interacting agents that meet within the immanent field.

I now must venture to say, along with Merleau-Ponty and Deleuze but in filmic terms, that the isolated, unified, Cartesian subject is a myth. Resnais helps us to look at how this myth is constructed, what its cinematic formal units are, how it is signified through film connotation. Just as in Godard’s Two or Three Things I Know About Her, Resnais presents a connotative system that can help us to clarify the reconcilability between phenomenology and a semiotics of cinema, for it illuminates the fundamental organizing process used in the secretion of film codes and deconstructs them in order to reveal a subject-position’s implication in the world. Such challenges to conventional film expression reveal to us the immanent field, providing us with a reflection on the filmic construction of the dualism between subject and object. This reflexivity has a particular aim, which many have understandably used to link filmmakers such as Resnais and Godard to the theater of Brecht. Discussing the rather unconventional montage of this film, Resnais himself stated: “This is cinema. We present you with real elements, sure, but we do not try to tempt you to believe that it is anything other than cinema. This is a type of honesty.”72 This “honesty” is the definitive value of a formalist approach to film-philosophy, for it permits us to understand how our larger systems of belief are formulated through the composition of subject-object relations laid bare in these texts. In the past two chapters I have progressively attempted to show this relationship as a function of the diegetic subject-function. But what if we take away this position? What of objective representation in cinema? To answer this question, I will return to the works of Jean-Luc Godard, whose deconstruction of the code of objectivity functions according to a reflexive principle summarized so well here by Resnais: “this is cinema.”