‘I don’t stop eating when I’m full. The meal isn’t over when I’m full. It’s over when I hate myself.’

Louis C.K., comedian1

THE COLD, GREY, November afternoon had done nothing to dampen the excitement of the Bath and Exeter rugby supporters as their teams competed in what turned out to be a fiercely contested end-of-season match. At the final whistle, Bath had trounced Exeter by 37 points to 15, leaving Bath fans jubilant and Exeter supporters downcast.

Just the sort of powerful emotions we had been hoping for!

We were about to carry out an experiment into the link between emotional arousal and overeating.2 In this experiment, groups of fans from each team were invited to attend a post-match analysis, hosted by well-known rugby pundits, in a nearby hotel. On arrival they were taken to separate meeting rooms and offered a buffet of pizzas, crisps, sausages and chicken nuggets, as well as bowls of salad and fruit. They could eat as much as they wanted and return to the buffet as often as they wished.

The discussions they had while eating were lively, informed and, at times, heated. What the fans did not know was that we were more interested in what went into their mouths than what came out of them. Previous research had shown that sports fans in America and France ate significantly more high fat and high sugar foods when their teams lost.3 The question we wanted to answer was, would English fans do the same?

They certainly did. Between them, supporters of the victorious Bath team consumed 8,000 calories, while defeated Exeter team fans ate almost 60% more at 13,412 calories.

But why?

What is the link between one’s emotional state and a desire to binge on highly palatable, energy-dense but nutrient-poor food? ‘It’s a form of self-medication’, according to George Koob of The Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California. ‘You’re modulating your arousal. People take the food to calm themselves down . . . In other words they relieve the itch.’4

In order to understand how this works, we need to look at the two very different reasons why we eat.

We’ve already touched on the ideas of homeostatic and hedonic eating in Chapter 7. The former, as the name suggests, is when we eat in order to maintain ‘homeostasis’, the essential internal balance on which survival depends. Homeostatic eating is when we eat in order to reach a genetically determined metabolic ‘set point’ and, as discussed earlier, it is primarily guided by the hypothalamus.

Hedonic eating, on the other hand, involves feeding not our physical appetite and the needs of our body, but rather our desires – the word ‘hedonic’ is derived from the ancient Greek hedone, meaning ‘pleasure’. A lot of hedonic eating takes place when we are trying to cope with either negative or positive emotions. We may, for example, use chocolates, cakes, biscuits or doughnuts as comfort foods when feeling bored, rejected, frustrated or depressed. Researchers have found, for example, that obese people consume significantly more chocolate when watching a sad film than a neutral one.5 However, we also eat hedonically when excited or as an aid to relaxation – take the super-sized bucket of popcorn that adds to our enjoyment of a trip to the cinema.

The foods we prefer when eating hedonically are almost invariably highly palatable and energy dense. And if we are eating for emotional reasons as opposed to physiological ones, we are rendering ourselves vulnerable to the excessive amounts of food available to us in the modern world; we are being tempted with the offer of the fix we crave almost constantly by advertising and displays of tasty treats. Further, the more prone a person is to emotional eating, the more sensitive they are to these food-related cues. Hypersensitivity to food cues, paired with an environment of plenty, creates the perfect storm, where weight gain is an obvious and – without appropriate behaviour modification tools – inevitable outcome.

In an ideal scenario, once we have eaten enough to satisfy our homeostatic needs, signals from the stomach will alert the brain to the fact that sufficient food has been eaten and those signals are attended to. Most people know when they have eaten enough and stop before feeling uncomfortably full. Furthermore, since the food is satisfying a physical need, the individual has no reason to feel regretful or ashamed.

This is not necessarily the case with hedonic eating; since food consumed for emotional reasons is usually hugely energy dense, our stomachs do not react to the energy content appropriately.6 If we compare 50 g of vegetables to 50 g of chocolate, we’ll notice the chocolate takes up significantly less space. Chocolate is immensely energy dense, which makes it difficult for the body to know when ‘enough’ has been ingested. This is typically the case with most junk foods; they are amazingly efficient vehicles of energy delivery, which means it can be easy to eat too much and thus gain weight.

Someone feeding their feelings might easily finish off an entire jumbo-sized bag of crisps because their appetite is not guided by physical sensations of satiety so much as a gnawing psychological need. Moreover, hedonically motivated eating can elicit feelings of guilt and shame; people aren’t sure why they have engaged in a binge, but do it in spite of their best intentions.

In her book Counting Calories, author Jane Olson discusses her own struggles with hedonic eating: ‘Comfort foods they may have been, but helpful foods they most definitely were not. By merging my identity with certain foods and thinking of them as old friends, I found myself in the food equivalent of a co-dependent, destructive relationship. If I was going to insist on relating to food as a friend, then clearly I needed new friends.’7

In a 2003 survey conducted by the American food magazine Bon Appétit, respondents ranked their favourite foods in order of preference as: ice cream, chocolate, cake, cheesecake, and potato chips.8 If a similar survey were conducted today in the UK or mainland Europe, our guess is that a similar order would be reported. In order to understand what makes these foods so special and so pleasurable when it comes to hedonic eating, we need to count up the number of ‘taste triggers’ (a term used in the food industry) that each possesses. There are six main taste triggers and it will probably come as little surprise to you when we say that food companies carefully design these into certain products in order to create what they call ‘bliss’ points – combinations of taste triggers that can make the foods so delicious they are arguably addictive.

Trigger One – Flavour: For maximum hedonic pleasure, food should contain salt, sugar, monosodium glutamate (MSG), and flavour-active compounds. Surprisingly, taste only accounts for 10% of the overall sensation of food. The optimal level for salt is between 1.0 and 1.5%; for MSG 0.15% and for flavour-active compounds 0.02%.9

Trigger Two – Dynamic Contrast: Many top-selling hedonic treats have high texture and flavour contrasts. Chocolate and ice cream, for example, start as a solid then melt into a liquid in the mouth; jam doughnuts combine fluffy dough with the satisfying wetness of the jam at the centre. The greater the contrast, the more pleasurable and rewarding the food will prove.10

Trigger Three – Evoked Qualities: The ideal food should evoke agreeable memories about where it was first enjoyed and our physiological and psychological state at that time. For example, the Valentine’s Day chocolates given by an admirer, the ice cream enjoyed on holiday, the scent of birthday cake candles blown out as a child. Even when no such actual memories exist, they can often be created through advertising and marketing.

Trigger Four – Food Pleasure Equation: The food pleasure equation is a calculation made in the food industry involving the relationship between the sensation of a food and the macronutrient stimulation it causes, the latter being to do with the combination of carbohydrate, fat and protein. The nicest foods maximize both elements, and if one is reduced in some way it will have to be compensated for in order for the food to remain as tasty – so if manufacturers reduce the fat in a product they have to enhance its palatability in some other way to ensure the same level of hedonic appeal. Typically this is achieved by increasing amounts of sugar and/or artificial sweeteners.

Trigger Five – Caloric Density (CD): Is a measure of how many calories there are in a food relative to its weight. On a scale in which water scores 0 and pure fat 9, food with a CD of between 4 and 5 is the most palatable.11 As we explained in Chapter 7, our gut has a variety of receptors, and foods with this ideal CD stimulate these to generate feelings of intense pleasure in the brain.

Trigger Six – Emulsions: The word, which comes from the Latin ‘to milk’, is used to describe a mixture of two or more normally immiscible (i.e. non-mixable or unblendable) liquids, such as the water and fat in milk itself. Examples of emulsions in food include ice cream, chocolate, butter, vinaigrettes, mayonnaise, and brewed coffee. Emulsions raise the pleasurable sensation of high fat/high sweet foods to a new level. For example, while butter contains about 2.5% salt in the solid state, the actual salt content experienced by the taste buds jumps to about 10% in the mouth.

One food which possesses all these pleasure triggers is chocolate.12

It was Christopher Columbus who, in the early years of the sixteenth century, brought cocoa beans to Europe from the New World. But it was the Spanish conquistador Don Hernán Cortés who first realised their huge commercial value. When initially introduced to Europeans, chocolate was marketed as an enjoyable drink with medicinal properties; it was said to cure a variety of health problems ranging from stomach ache to depression. Today, although they may not realise it, many of those who comfort-eat chocolate are using it for the same reasons.

Chocolate manufacture and sales is a multibillion-dollar business, the value of which exceeds the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) of more than 130 nations. Americans consume over $13.1 billion in sales annually, amounting to three billion pounds of chocolate.13 The annual per capita consumption of chocolate in the States is 13 lb (6 kg) and more than half (52%) of adults prefer the flavour of chocolate to both vanilla and fruit.14 Europe loves chocolate even more, with an annual per capita consumption a shocking 22 lb (10 kg). At the other end of the scale, India and China’s chocolate consumption rates are among the lowest; the Chinese eat less than 6 ounces a year and the Indians just 3.5 ounces. These low numbers are, however, likely to rise sharply in coming years as the economies of these countries continue to grow, and their populations’ taste for indulgent treats along with them.15 So let’s take a look beneath the wrapper to see what it is about chocolate’s chemistry that makes it both powerfully appealing and seriously addictive to men and women alike.

Few of the millions of chocoholics around the world appreciate the potent effect their favourite treat has on their brain. Chocolate has a psychoactive effect so powerful some researchers believe it should be considered not confectionary but a drug. Among other compounds, a piece of chocolate contains:

In 2006, Gordon Parker and Joanna Crawford from the Prince of Wales Hospital in Sydney, Australia, reviewed all the possible theories as to why people develop chocolate cravings.18 After analysing the responses of almost 3,000 adults with clinical depression, they concluded that the fat and sugar activate both dopamine and opioids (the latter being the term for any chemical which has similar effects to morphine and its derivatives) in a strong but dysfunctional manner and that this results in overconsumption.19 Which is to say that people who do suffer with depression may be vulnerable to overeating chocolate because it enhances mood. This dopamine-opioid rush, in combination with calories in the form of fat and sugar, also has effects on receptors in the gut. This is why, like any addictive drug, eating chocolate even once increases the likelihood of it being eaten again and again.

Research into addictive behaviour indicates that dopamine receptors in the striatum (in a part of the brain called the basal ganglia, see Chapter 7) work in tandem with frontal regions in the brain, where decisions about whether or not to eat are made. Obese individuals show an enhanced response in this region of the brain when anticipating food, which increases their risk of overeating.20

Furthermore, dopamine receptors will eventually shut down if they are overstimulated. As with drug addiction, repeated overconsumption of highly palatable foods can result in long-term neuroadaptations in the brain’s reward and stress pathways. The brain seeks to maintain homeostasis, normal balanced operations, by removing or blunting the sensitivity of dopamine receptors. This means that larger and larger quantities of the rewarding substance are required to produce the same pleasurable effect. This is why a junkie has to constantly increase doses of heroin or cocaine to experience the same high. In the same way, a person who is gaining weight from bingeing on chocolate or other HED foods will find that they too must increase the amounts they consume in order to get the same satisfaction. This, inevitably, diminishes their ability to control the amount they eat and significantly increases their risk of substantially overeating.21

In a study of sugar bingeing, Nicole Avena, Professor of Psychology at Columbia University, placed rats on a daily schedule of 12 hours without food, followed by 12 hours unlimited access to a sugar-rich diet consisting of standard rodent chow plus a solution of 25% glucose or 10% sucrose.22 After only a few hours, they started to binge on the super-sweet solution, their desire for sugar having apparently surged. They also showed an increased desire to obtain sucrose, pressing the lever which delivered the treat more vigorously after being deprived of the extra sugar for a couple of weeks.23 The rats’ daily feeding patterns also shifted as they started to consume more and more sugar meals.

‘After a month of binge eating sugar,’ Avena reported, ‘rats show a series of behaviours similar to the effects of drugs of abuse, including the escalation of daily sugar intake and increase in sugar intake during the first hour of daily access.’24

The similarities with drug addiction was further demonstrated when the researchers injected rats that had been binge eating sugar with naloxone. This opioid-receptor antagonist is used on humans to counter the effects of heroin or morphine. After receiving the drug, the rats showed withdrawal symptoms, such as teeth chattering, forepaw tremor, and head shakes.25 As with any other addicts, the animals had become so hooked on sugar they had to have more and more of it in order to achieve the same level of reward and satisfaction. So sugar is not only a source of energy, but a potentially addictive source of chemically based pleasure.

One of the most important factors in the development of binge eating is a prior history of food restriction or energy deprivation. Energy deprivation can serve to enhance the sensory qualities of food even further, meaning that by going on a diet a person can inadvertently make themselves more likely to indulge in binge eating if their self-control snaps. Moreover, the depression or negative mood experienced when food intake is limited lifts immediately when we eat foods that are high in sugar and fat. This improvement is likely due in part to a surge in dopamine production.26

This supports the notion that, during a binge, emotion-driven eaters are especially powerfully attracted to what they regard as ‘forbidden foods’.27 The accompanying surge in dopamine, which is the result of the higher sugar and energy content as well as the result of caloric restriction, makes these foods much more rewarding to individuals in a state of energy depletion. This means that for anyone on a diet the temptations and the rewards offered by such ‘forbidden foods’ can prove almost impossible to resist.

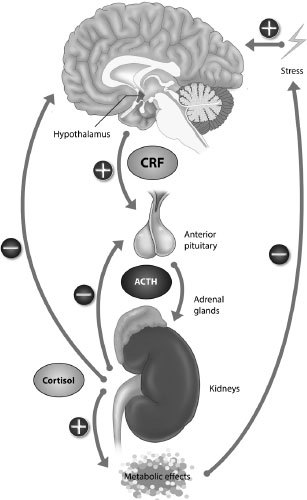

It’s also important to understand the part that stress can play in overeating. Prolonged stress upsets the regulation of a vitally important pathway between brain and body known as the Hypothalamic Pituitary Adrenal (HPA) Axis – see Figure 9.1 – which affects both how much we eat and how that food is metabolised.

Stress causes the hypothalamus, described in Chapter 7, to excrete a substance called Corticotropin-Releasing Factor (CRF). This is transported through the bloodstream to the pea-sized pituitary gland, which is attached to the hypothalamus by a short stalk. There it stimulates the release of a particular hormone, the adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), and then travels, again in the blood, to adrenal glands located above each kidney. It stimulates them to secrete a group of hormones known as glucocorticoids. The most potent of these, cortisol, increases blood glucose levels and breaks down proteins and fats to help make energy available.

When a person is severely stressed, their cortisol levels may increase as much as tenfold. Continuous activation of the HPA axis contributes to insulin resistance, which forces the body to store sugar as fat, as well as affecting a number of hunger hormones such as leptin and ghrelin, which stimulate appetite and contribute to overeating. It can also heighten cravings for desserts and snacks, especially among those who are already overweight.28

The HPA axis overlaps with the limbic and emotional regions in the brain (i.e. the amygdala, hippocampus and insula), all of which play a critical role in the experience of reward, and rewarding behaviour. This helps explain why, when stressed or depressed, many people comfort-eat HED foods.

What it does not explain is why this results in some people doing so to excess under stress, while others, although just as stressed, are able to restrain themselves. It is a paradox which, in 2013, Gudrun Sproesser and her colleagues from the University of Konstanz set out to solve.29

When stressed, four out of ten people (43%) seek relief by increasing their hedonic consumption of energy dense foods. These people are termed ‘hyperphagics’ or, in Sproesser’s terminology, ‘Munchers’. However, almost as many (36%) eat less when stressed – they are hypophagics or ‘Skippers’.

While accepting that Munchers did indeed eat more when experiencing negative emotions, Sproesser and her team wondered whether they might eat less than normal when in a regular, happy or otherwise more positive mood.

‘Focusing on eating responses to negative situations might lead to the conclusion that stress hyperphagics are prone to overconsumption,’ Sproesser comments, ‘whereas a more comprehensive view, including responses to positive situations, might show adaptive eating behavior.’30

In the final mix of volunteers for Sproesser’s experiment, one third (32%) were Munchers and the rest (68%) were Skippers. At the start of the experiment, each person watched a video featuring an agreeable individual of the same sex as the subject themselves, who described his or her interests, likes and dislikes. They were told that he or she might want to meet the participant – it all depended on how well they came across in a video they would make about themselves in return. After making this video and supposedly having had it viewed by the other student, they were randomly assigned to one of three groups, each of which was given different feedback as to how their video had been received.

Those in the ‘social acceptance’ group were informed the other student was looking forward to meeting them. Those allocated to the ‘social rejection’ group were told the other student did not want to meet up. The third, ‘control’ group was told that, unfortunately, no meeting could take place because the student had dropped out of the study.

Next all three groups were asked to taste three different ice creams. They had to report how much they liked them and whether or not they would buy them. Once the tasting session was completed, they were invited to eat as much ice cream as they wanted. As expected, the Munchers who had experienced ‘social rejection’ ate significantly more ice cream, while rejected Skippers ate significantly less in response to the same negative emotions.

Less expected and more interesting was the discovery that with ‘social acceptance’ and its accompanying positive emotions, this pattern of consumption was reversed. Now Munchers ate less ice cream and Skippers more.

The ‘take home’ message from this research is that emotional stimulation, whether positive and pleasurable (such as social excitement) or negative and painful (such as rejection), contributes to hedonic eating. It’s understandable why this should be the case. The pleasure which the food provides is a form of escapism from a situation that is pushing us towards emotional extremes. Furthermore, eating in this way provides extra glucose to the brain to help it cope with a demanding situation. The unwelcome consequence is that the body is left to metabolise these excess calories. Moreover, if this strategy becomes habitual, the individual runs the risk of exhausting their insulin receptors, which will contribute to insulin resistance and increase the risk of developing diabetes.

So far in this chapter we have considered food consumption, especially hedonic eating, as a way of controlling emotions. But in some situations, food becomes not an answer – admittedly an unhelpful one – to emotional upsets, but their cause.

Imagine someone who starts their day at 7 a.m. by breakfasting on the following: coffee with full cream milk and two heaped teaspoonfuls of sugar; toasted white bread with strawberry jam, and a bowl of cornflakes. This satisfies their hunger at the time, but around 11 a.m. they start to feel not just peckish but also lacking in energy and a bit down. They have caught a dose of the hypoglycaemic blues. While the symptoms vary from one person to the next, these mid-morning blues typically include: anxiety, depression, lethargy, shakiness, irritability, dizziness, impaired concentration and daydreaming.

Looking back at the list of foods eaten at breakfast, it’s pretty easy to work out the cause of these symptoms. All were medium to high on the Glycaemic Index (GI), which is a system for measuring how rapidly blood glucose levels are likely to rise after eating a particular food. Foods with a GI of less than 55 are rated as low; between 56–70 as medium and from 71 plus as high.

Since the speed at which blood glucose rises is influenced by the amount of carbohydrate in the food, it is also useful to consider a second factor, the Glycaemic Load (GL), which takes into account the amount of carbohydrate in the food and how much each gram raises blood glucose levels. In layman’s terms, GI is how fast a food raises blood sugar, and GL is how much it raises it in total.

A GL of less than 10 is rated low, 11–19 as medium and greater than 20 as high.31 Foods with a low GL will nearly always also have a low GI. Those with a medium-high GL can vary in their GI from very low to extremely high – watermelon, for example, has a high GI (up to 83) but, since a typical serving contains only a small amount of carbohydrate, has a low GL of around 4. Fructose (fruit sugar) has a low GI (11 per 25 g) and GL of only 1.

That said, foods with a low GI and GL can still cause a significant increase in blood glucose levels if they are consumed in large quantities. One lady interviewed during one of Margaret’s investigations at the Kissileff Eating Lab at the University of Liverpool, for example, was putting on weight despite claiming that she ate only oranges. This seemed unlikely, until she admitted to eating more than thirty a day! While the amount of fructose in a single orange poses no problem, multiplied by 30 a day – 210 a week – it most certainly does!

With this in mind, let’s take a look at the breakfast menu and note the GI and GL numbers of the food eaten.

In order to deal with all this sugar, the body produces increased amounts of insulin. The authors of The New Sugar Busters! Cut Sugar to Trim Fat liken insulin to a biological broom which: ‘. . . sweeps glucose, amino acids, and free fatty acids into cells where potential energy is stored as fat and glycogen to be used later.’32 As we explained in Chapter 4 insulin is manufactured and secreted by beta cells in the pancreas. A healthy pancreas will secrete between 25 and 30 units (a unit here being 35 micrograms) of insulin each day and store around 200. Insulin works together with another hormone, glucagon, to maintain blood glucose at a healthy level. The former prevents it from rising too high and the latter ensures it does not fall too low. For these reasons insulin has been described as the ‘feasting’ and glucagon as the ‘fasting’ hormone. After insulin has done its work, the level of sugar in the blood declines rapidly and may even end up below its normal level. This is known as a ‘sugar crash’ or, as a doctor would describe it, ‘hypoglycaemia’ (see Figure 9.2).fn2

If you have encountered these midday doldrums, you may have noticed that, as we described earlier, your first impulse is to eat HED snacks, in order to bring your blood glucose levels back up. Here are some of the treats which people typically consume for this purpose, together with their GI and GL figures:

Chocolate bars (per 50 g = GI 55:GL 14)

Bags of crisps (per 50 g = GI 58:GL 12)

Chocolate chip muffins (per 60 g = GI 58:GL 17)

Iced cup cakes (per 38 g = GI 85:GL 19).

Consuming these sorts of foods, high on the Glycaemic Index, results in another rapid rise in blood sugar levels, lifting the mood and restoring energy levels. Unfortunately this relief is short lived. The sugar spike is soon followed by a further crash when the body releases insulin to regulate itself once more. The result is that blood sugar and insulin levels fluctuate wildly and unhealthily.

For those with a weight problem, this roller-coaster ride of insulin spikes and sugar crashes is particularly bad news. High insulin levels increase the storage of sugar in liver and muscle as glycogen. Insulin also activates the enzyme lipoprotein lipase, which is responsible for removing triglycerides (a type of fat) from the bloodstream and storing in fat cells. It also inhibits lipase, another enzyme, whose job is to break down stored fats. The overall result is an increase in both fat storage and, inevitably, body mass, especially around the abdomen.

Unfortunately the bad news doesn’t end there. When insulin is overproduced, both liver and muscle cells can become increasingly insensitive to it, and therefore resistant to normal levels. As a result, ever more must be manufactured in order to restore blood sugar levels to normal. This can create a downward spiral, ending with a failing pancreas and Type II diabetes.

And not only does insulin play a vital role in physiological health, but increasing evidence suggests it is also important in maintaining psychological health. In the elderly, for example, insulin sensitivity has been shown to have a positive correlation with verbal fluency, brain size, and the volume of grey matter in regions responsible for speech.33 Insulin receptors are located in close proximity to the hippocampus, which is responsible for establishing long- and short-term memories, regulating mood, and also spatial orientation. For these reasons it has recently been proposed that insulin resistance (one of the hallmark signs of the development of diabetes) contributes to cognitive decline.34

With the biology and psychology of weight gain now described, we need to turn our attention to the world in which these systems function. A world which, as we have already explained, is very, very different from the one in which we evolved. It is a world beset with traps for the innocent, the unwary and the uninformed. A world in which the search for corporate profits is helping to make consumers fat.

fn1 Monoamine Oxidase inhibitors (MAOI) are a group of medicines used to treat depression. They include: isocarboxazid, phenelzine, moclobemide and tranylcypromine and appear under various different brand names.

fn2 This describes the condition in an adult whose blood sugar level is below 50 milligrams per decilitre (mg/dL), which is dangerously low and may lead to mental decline; dropping below 40 or 30 mg/dL can lead to seizures.