Throughout human history, we have constantly clashed with large carnivores. People kill predators because predators kill livestock (and sometimes us) or simply because they represent the greatest challenge for human hunters wishing to prove themselves; historically, anyone who could kill a lion was an important person, regardless of the actual threat the lion represented. As a fairly inoffensive cat which generally shuns humans and their livestock, cheetahs have probably suffered less at the hand of man than many predatory species until fairly recent times. Indeed, for much of the last 2000 years, trained cheetahs were revered as hunting companions from North Africa to India.

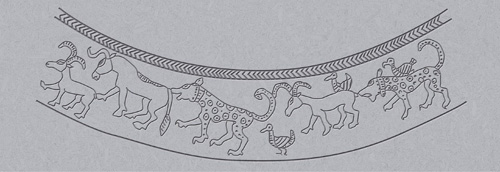

Illustration of a detail on an engraved vase from the Maikop burials, Caucasian Russia. The collared animals are widely assumed to be trained cheetahs (after Vereshchagin, 1967, The Mammals of the Caucasus).

(David du Plessis)

Modern science knows the cheetah as Acinonyx jubatus. Refined and standardised by the Swedish biologist Carolus Linnaeus in the 1750s, the system of labelling every species with its own two-pronged name is far more than scientific vanity. The Linnaean name is unvarying in every country of the world, no matter the language spoken or the local name by which an animal is known. This means, for example, that if an Iranian biologist needs to communicate with a veterinarian in Kenya, neither needs to know the common name of the cheetah in Arabic, Kiswahili, or for that matter in any language at all.

Additionally, the name contains information about the species’ evolutionary relationships. In the case of the cheetah, the genus name Acinonyx is shared by no other living animal. Compared to the genus Panthera, which contains the closely related lion, tiger, leopard and jaguar, it indicates that the cheetah has no near relatives alive today. (See Chapter 2, pages 26–41, for a detailed discussion of the evolution of cheetahs.)

This uniqueness is reflected in the origin of the name. Its exact provenance is debatable, but is clearly inspired by some of the cheetah’s most characteristic features, traits it shares with no other cats. Acinonyx is thought to derive from two Ancient Greek words, akantha, meaning thorn, and onux, a claw, which is a reference to the cheetah’s dog-like claws. An alternative derivation occasionally offered is more specific: a and kino, Greek for ‘not’ and ‘move’, perhaps in recognition of the cheetah’s poorly developed ability to retract its claws. The species name jubatus derives from the Latin iubatus, meaning ‘maned’, referring to the distinctive cape of light fur with which cheetah cubs are born (though as the earliest scientific descriptions of the species were made from a grown animal, probably in the mane’s less obvious adult form).

The cheetah’s common name is thought to stem from the Sanskrit chitraka, meaning speckled or spotted. The Sanskrit gave rise to the Hindi word chita (and the variants cita and citah), also referring to the cheetah’s spotted coat, and it is the Hindi term that was ultimately anglicised into the name used today.

It may seem incongruous that an ancient Asian word has named a species that is essentially African. However, the cheetah once had a distribution that far exceeded its present range. Until at least the late 19th century, the cheetah was found in most of Africa, throughout the Middle East and Central Asia, northwards as far as modern-day Kazakhstan and east into India, where its range petered out just shy of the border with Bangladesh (see the map on pages 22–23). Indeed, it was throughout the cheetah’s former Asiatic range where they once enjoyed man’s unparalleled esteem, arising mostly from the extraordinary practice of using them as hunting companions. The name that has endured derives from a time and place when cheetahs were revered.

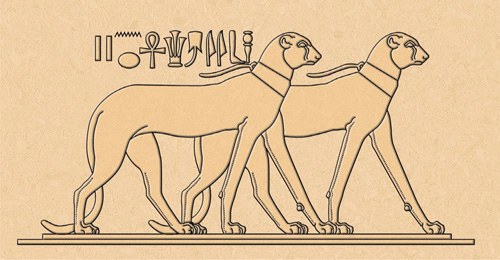

A pair of collared cheetahs with leashes, depicted in a bas-relief from Thebes, c 1700 BC (illustration after Prisse D’Avennes, Histoire de l’Art egyptien T. II, pl. 13).

(David du Plessis)

CHEETAHS AND HUMANS IN HISTORY

The first recorded appearance of cheetahs in human history dates from before the time that permanently settled cultures arose in our species, but not by a great deal. Although humans have been depicting animals for at least 50 000 years, cheetahs are curiously absent until relatively recently. Cheetahs have not been found among the superb Eurasian cave art depictions of Paleaolithic fauna, perhaps because carnivores were not particularly valued as food or because cheetahs were not considered dangerous; formidable carnivores such as lions and bears feature prominently. The earliest indisputable image of a cheetah is a life-sized rock engraving from Niger’s Aïr Mountains, made at least 7 000 years ago. Later human cultures occasionally included them in their art: a painting in Chad’s Ennedi Mountains is between 2 000 to 3 000 years old, and cheetah representations left by ancient civilisations in India are dated between 2500 and 300 BC. By that time, however, more sophisticated records of cheetahs had begun to appear elsewhere. At least as early as 1650 BC, the ancient Egyptians tamed cheetahs. Numerous beautifully rendered depictions of cheetahs on the tombs of royalty show them wearing collars and being led on leashes, often to be given as highly prized tribute to the pharaohs.

Cheetahs, lions and leopards were all depicted by the ancient Egyptians in their art. This unusual head, combining the features of a lion with the cheetah’s unique tear streaks, is from one of Tutankhamun’s funerary beds, discovered in his tomb in the Valley of the Kings in 1922 and now in the Egyptian Museum in Cairo. It is made from gilded wood with the details picked out in blue glass. It dates to the New Kingdom and the reign of Tutankhamun around 1330 BC.

(© Ancient Egypt Picture Library)

Scene from a wall painting on plaster from the New Kingdom Tomb of Sennedjem at the Workman’s village of Deir el Medina on the west bank of the Nile at Luxor. Sennedjem was an architect/artist in the Royal Necropolis. The scene shows Sennedjem’s eldest son dressed as a priest, making an offering to his deceased father and mother. As a priest, he wears a cheetah skin draped over his shoulders. The tomb dates to around 1200 BC.

(© Ancient Egypt Picture Library)

The ancient Egyptians are credited as the first to keep cheetahs, but whether or not they used them for hunting is contentious. Indeed, the origin of hunting with cheetahs is very often reported as early as 4 500 to 5 000 years ago, among either the ancient Egyptians or the earlier Sumerians who established the world’s first city between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers in modern-day Iraq. There is also a silver vase from the Maikop burials in Caucasian Russia, dated to the middle of the third millennium BC, which appears to show collared cheetahs chasing various ungulates (antelopes and their relatives). However, none of these sources clearly demonstrates coursing with cheetahs (as opposed to simply keeping them) and their use in hunting among such early cultures has been assumed, but not demonstrated. Given that many early depictions show cheetahs wearing some of the distinctive hardware of trained animals – leashes, collars and harnesses – it is not unreasonable to suppose that they were used as hunting companions by these civilisations, but unequivocal evidence is still lacking.

It is not until the time of Christ that hunting with cheetahs was unambiguously present. During the first millennium AD (and later), it was practised in north Africa, on the Arabian peninsula, throughout the modern-day Middle East, Iran, Iraq, Pakistan, India, Mongolia, and possibly into China. Hunting with cheetahs in the fifth century was known from the southern provinces of the former Soviet Union, and in the same period, trained cheetahs were imported into Constantinople by the Byzantine emperor, Anastasius. Russian nobility continued to hunt with cheetahs during the Middle Ages, while nobles in Italy and France embraced the sport from about the 10th century. It flourished in continental Europe especially between the 13th and early 16th centuries. Keeping cheetahs had always been the domain of nobility but particularly so in Europe, where owning the land on which to hunt with them required considerable resources. The sport fell out of favour with European royalty during the 16th century, and despite a failed attempt by Leopold I, Emperor of Austria, to revive the hunting of hares with cheetahs around 1700, had vanished from western Europe by the early 18th century.

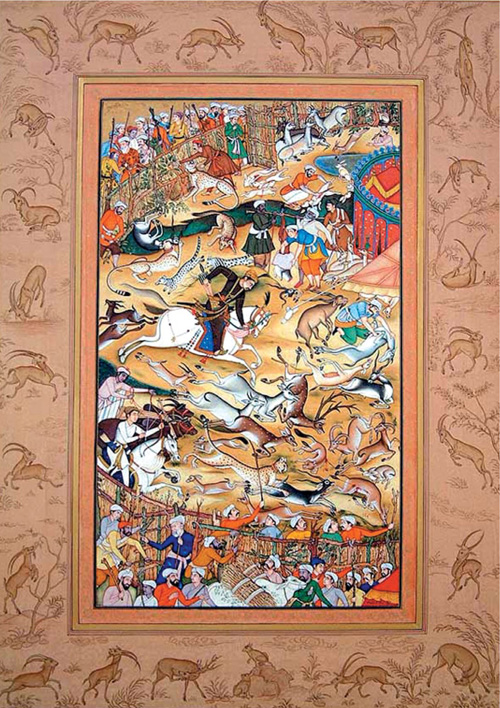

Depiction of a shakhbandh hunting scene at Akbar’s court. The very accurate portrayals of species provides valuable information on which animals were hunted with cheetahs. Here, as well as the favoured Indian blackbuck, the cheetah’s quarry includes chinkara, chital, markhor, nilgai, urial and hares.

(Miniature Painting on Paper by Kailash Raj. By kind permission of Exotic India, www.exoticindia.com)

It had, however, endured in Asia. Hunting with cheetahs reached its zenith in India, and it is from there that we have the most detailed accounts of the practice. It is unclear when cheetahs were first trained to hunt in India but by the time of the great Mughal emperors in the 16th to 18th centuries, it was practised on a scale that no culture has equalled. Probably the greatest practitioner the world has seen was Akbar the Great, who ruled from 1556 to 1605. His son, Jahangir (himself a devoted hunter who once caught 426 antelopes with cheetahs in a hunt that spanned 12 days) reported that at one time Akbar had 1 000 cheetahs in his hunting stables. Over his 50-year reign, Akbar is recorded as having owned 9 000 cheetahs.

CHEETAH ATTACKS ON HUMANS

The Mughals and others subdued wild cheetahs using nets, ropes and their bare hands, yet there are no records of a cheetah ever killing a captor in self-defence. In fact, there is no record of wild cheetahs ever killing a human at all. Tame individuals occasionally maul people, particularly children – a toddler attacked by a pet cheetah in Namibia was clinically dead for some minutes before a family member revived him – yet there are no verifiable accounts of even children being taken by a wild cheetah.

Given that cheetahs can kill prey considerably larger than people, there is little doubt that they could overpower a human if so inclined. That they do not is probably due to a combination of factors, particularly the cheetah’s reluctance to confront large predators and its preference for gazelle-type prey (see Chapter 5, pages 88–115, for details on diet). As upright, group-living, large-bodied hunters, humans are both too dangerous and too different to be on the cheetah’s menu.

Like those earlier cultures that had practised hunting with cheetahs, the Mughals captured them as adults. They recognised that cubs were not equipped with the skills to hunt, and except for a single litter of three born during Jahangir’s reign, never succeeded in breeding them. Cheetahs were caught by means of deep pitfall traps dug in game trails they were known to use – a method that occasionally resulted in the cheetah breaking its tail or leg. Akbar, whose personal interest in the cheetah was peerless, refined the technique by digging shallower pits and devising a sophisticated trapdoor that closed after the cheetah was caught. His method eliminated the problem of injuries and ensured that the cats could not escape. The Mughals also caught cheetahs by running them to exhaustion on horseback, or by laying snares of deer-sinew around ‘favourite trees’. Intriguingly, the latter method is echoed in the modern practice of setting cage traps around play-trees, the most widely used technique to trap cheetahs in Namibia today (see Chapter 6, page 124).

Because it was always adult cheetahs that were procured, they were already skilled hunters, yet all newly caught cheetahs underwent a period of training. The training served primarily to tame the wild animal and habituate it to the process of hunting with people rather than actually teach it to capture prey. Even so, cheetahs in training were commonly loosed on antelopes that had been deliberately injured, as though they required practice. In any case, most cheetahs were ready to be taken hunting within three to six months, though it sometimes took up to a year and Akbar is credited with refining the training period to just 18 days.

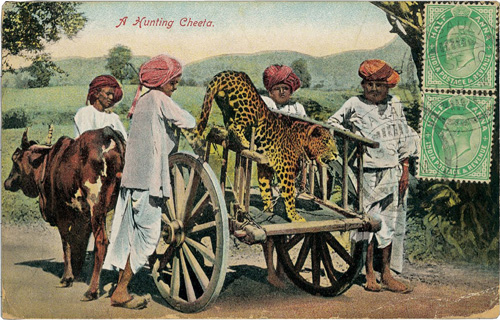

A unique photograph from around 1900 showing a tame adult male leopard being transported in the manner normally reserved for trained cheetahs (and wrongly labelled as such). Leopards are not nearly as amenable to human contact as cheetahs and it is likely that they were kept like this on very rare occasions.

The Mughals transported cheetahs to the hunt on small carts drawn by bullocks, a practice that had been adopted by numerous cultures before them and persisted after. The method exploited the indifference of many ungulate species to bullock carts, which were ubiquitous among peasants throughout Asia and represented no threat (unless, of course, they carried a cheetah!). In parts of India, Iran, Syria, Mongolia, Kazakhstan and Europe, cheetahs were also carried to the hunt on horseback, having been trained to sit behind the saddle, sometimes on a flat seat or a small rug specially designed for them. In the dying stages of the sport in the early 20th century, motorcars were used to ferry cheetahs to the hunt. Whatever the transportation, cheetahs were routinely blindfolded until they reached the quarry. The practice was adapted from falconry in which the hood serves to keep the bird calm, though whether it made a difference to cheetahs (which, once tamed, are less highly strung than raptors) is not recorded. Some cultures kept their cheetahs blindfolded constantly, except when they were hunting or being exercised.

On sighting a herd of antelopes, the hunters adopted a number of different tactics. The most common and straightforward method entailed a careful approach to within a reasonable distance from the quarry (usually recorded as the equivalent of 100 to 300 metres), whereupon the blindfold was removed and the cheetah set free to begin the chase. However, the Mughals employed a number of variations, knowing each by specific terminology. They positioned the cheetah downwind of the herd and then moved the cart in the opposite direction, drawing the attention of the prey while the cheetah stalked. They also lay in wait with many cheetahs while beaters drove prey towards them and then loosed the cats as the herd was upon them, often making many kills. Finally, cheetahs were also used in shakhbandh, great stockades created of branches and trees that hemmed in the prey.

When the cheetah captured its target, handlers rushed to slaughter the prey according to halal, and rewarded the cheetah with a small bowl of blood or some of the internal organs. Non-Muslim cultures also typically removed the cheetah from its catch, perhaps so that it could be hunted again or possibly to retrieve the trophy’s skin before it was damaged. The main quarry was the blackbuck, a member of the gazelle tribe endemic to the Indian subcontinent. Male blackbucks were more sought-after trophies than females. Indeed, the Maharajas who continued with the sport after the downfall of the Mughal Empire apparently trained cheetahs to select only males by withholding their reward for a kill if they took a female. Supposedly, cheetahs learned to kill only male blackbucks within six months. Other species that were hunted included the chinkara (a small Asiatic gazelle) and, less often, the large Indian nilgai, as well as wild goats and sheep such as ibex, markhor and urial. Paintings of the shakhbandh hunts show many small carnivores such as civets and foxes caught up in the drive, but these were probably not intended as targets for the cheetahs. In the Central Asian republics of the former Soviet Union, goitered gazelles, foxes and hares were hunted with cheetahs.

Hunting with cheetahs declined with the demise of the Mughal Empire in the early 1700s, though it remained popular with Indian nobility until very recent times. With the occupation of the region by the British, both the sport and the cheetahs were consigned to oblivion. The British were largely uninterested in coursing with cheetahs – somewhat ironic given the fact that they called the cheetah the ‘hunting leopard,’ a name derived from the sport. Instead, wildlife was fair game to the British and they hunted wild cheetahs assiduously, usually by rifle but sometimes by spearing them from horseback or setting dogs on them. British India also imposed bounties on cheetahs from 1871 (and possibly earlier), when the cheetah was already scarce and declining. Indian royalty continued to hunt with cheetahs well into the 20th century but by 1914, the species was so rare in India that animals were being imported from Africa, particularly Kenya. The last records of coursing with Indian cheetahs are thought to be from around 1930; later records as recent as 1960 used African cheetahs. Coursing was still known from modern-day Turkmenistan until 1949, most likely with Asiatic cheetahs which persisted in the region until the early 1980s. Today, wealthy Arab men in Saudi Arabia, Oman and the United Arab Emirates illegally import cheetahs from Somalia, apparently with a view to resurrecting the practice of hunting gazelles on the Arabian peninsula. The widespread decline of suitable prey there makes such a revival unlikely.

HUNTING WITH CARACALS

The Mughals and other great Asian hunting cultures apparently tamed cats other than cheetahs, among them lions, tigers and leopards, but the terminology used is often ambiguous. For example, the names for cheetahs and leopards were often interchanged, so the extent to which these other species were kept is very vague. However, it is clear that the only felid (cat) other than cheetahs that was regularly trained for hunting was the caracal.

Caracals were used for hunting in India from at least the early 1300s and almost certainly earlier. The process of catching, training and hunting with them was very similar to the details we know for cheetahs, and some early photographs of hunting parties show the two species together. Caracals were sent after hares and foxes, and even up trees for arboreal squirrels, but game birds such as peafowl and partridges were the most popular quarry. One variation of the hunt entailed loosing the caracal on flocks of pigeons feeding on the ground to see how many it could kill as the birds took flight; up to a dozen is recorded, though this may be an exaggeration. Hunting with caracals persisted among Indian princes until about the same time as coursing with cheetahs.

THE CHANGING DISTRIBUTION OF THE CHEETAH

Ironically, the demand for live cheetahs over the centuries may have set the scene for its eventual extinction throughout most of Asia. The Mughals and Maharajas employed great networks of cheetah-catchers to secure adult animals from across their realm. Assuming the estimate of Akbar’s personal tally of cheetah is accurate, the numbers of cheetahs taken from the wild between his reign and the early 20th century must have been many tens of thousands at minimum. As a species that naturally occurs at low densities, this may have been enough to trigger a decline from which recovery was impossible once later cultures devoted themselves to outright persecution of the cheetah and its prey. Had Akbar or his descendents succeeded in breeding them instead of relentlessly removing them from the wild, the cheetah might still be part of the Indian fauna today.

The last known Indian cheetahs were shot in 1947 by the Maharaja of Korea, a former state in the northeast of the country (unrelated to the Asian country of the same name). He encountered three young males while driving at night and shot them in his headlights, taking only two bullets: one shot killed two animals, passing through the first cheetah to kill a second standing behind it. Even for the era – one when tiger hunts were still common – both the cheetah’s extreme scarcity and the wantonness of the act were recognised, and the editors of the Journal of the Bombay Natural History Society at the time published a scathing rebuke that accompanied a description of the specimens. Although the three males were probably not the last remaining Indian cheetahs – possible sightings continued sporadically until the 1960s – their deaths augured the extinction of the species in India.

Today, the Asiatic cheetah occurs only in Iran, where it is critically endangered. Estimates from 2002 put the numbers at fewer than 60, most of them in the vast arid steppes bordering the Kavir Desert in north-central Iran.

In Africa, the cheetah has fared better, but has also undergone an extreme reduction in numbers and range. Historically, cheetahs have been recorded from 38 nations in Africa (see the range map on pages 22–23). Although their presence has never been noted from a cluster of 10 countries on the West African coast, it is likely that cheetahs occurred in at least some of them prior to detailed verbal or written records. Cheetahs have probably extended their range periodically during cyclical periods of cooler, drier weather when the spread of rainforest contracted, allowing the invasion of woodland savannahs and their characteristic fauna.

Today, in addition to Iran, cheetahs occur in 29 African countries at most. Many of those have no current information on the species and it is probably extinct in some (see Chapter 6, pages 116–125 for more detail on status of the cheetah). The last great strongholds of the cheetah are in the tourism hotspots of East and southern Africa, where they are valued for their high visibility. Until quite recently, the cheetah was a widespread and relatively numerous species held in even greater esteem by people than it is today. Let us hope that future historians do not document its disappearance at our hand.

George Stubbs’ depiction of an attempt to course with an Indian cheetah in Windsor Great Park, Britain c 1765. Presented to the Duke of Cumberland for the royal menagerie at Windsor, the cheetah famously refused to run at a red deer stag despite its handlers’ best efforts at encouragment. The cheetah wears characteristic hunting gear; the kamarkach (waist harness), patta (collar) and tamancheki topi (hood).

(© Manchester City Galleries)

This detail shows Italian nobility hunting with cheetahs, and illustrates a popular European method of transporting cheetahs to the hunt – on horseback. From Benozzo Gozzoli’s (1420-1497) Procession of the Magi in the Palazzo Medici Riccardi in Florence.

(© Photo SCALA, Florence)