11

Sacroiliac Joint Screening

Before I set about guiding you through a comprehensive assessment protocol for the pelvis, I believe that it makes sense to look first at the standard testing procedures for screening the SIJ. In this way we might be able to determine if the actual SIJ is responsible (or partly responsible) for a patient’s presenting symptoms; the screening process, on the other hand, may lead us to conclude that the SIJ is not involved.

Let me give you an example of why I might do the screening tests for the SIJ first. When patients present to my clinic with pain in the area of, let’s say, the lower lumbar spine and/or pelvis, I will naturally always screen the hip joints for any underlying pathology (as I demonstrated in Chapter 7 on the hip joint), because I personally consider this area of the body (hip joint) to potentially be responsible in part for their presenting symptoms of back or pelvic pain. In this case I can at least then decide if I need to investigate the hip pathology/dysfunction a little further. These clinical findings would probably make me reconsider and alter my treatment strategy to now focus on the area of the hip joint complex rather than specifically on the area of the lumbar spine or pelvis, especially if I wanted my treatment to have a longer-lasting effect of reducing my patient’s ongoing painful symptoms in their lower back and pelvis.

Schamberger (2013) talks about the concept of malalignment syndrome and considers that 80–90% of all adults present with their pelvis out of alignment. Rotational malalignment is by far the most frequently seen, with an anterior rotation to the right innominate bone and a compensatory posterior rotation to the left innominate bone by far the most common (in approximately 80% of patients). This type of rotational malalignment can occur either on its own or in combination with other presentations (upslip/out-flare/in-flare; see “Pelvic Girdle Dysfunctions” section in Chapter 12). An upslip presents on its own in around 10% of patients, and in combination with the other types (rotational/out-flare/in-flare) in another 5–10% of patients. Out-flares and/or in-flares are present in approximately 40–45%, either in isolation or in combination with one or both of the other types.

Klein (1973) also shows that malalignment of the pelvis is present in 80–90% of high-school graduates. Of these, around one-third are asymptomatic and two-thirds are symptomatic, where they present with, for example, lower back or groin pain. Klein talks about three common presentations that account for 90–95% of those subjects found to be out of alignment:

1. Rotational malalignment—either an anterior or a posterior innominate rotation, or a combination of both (approximately 80–85%).

2. Out-flare/in-flare (40–50%).

3. Upslip (15–20%).

Remember, the history taking for your patient is one of the most important components when trying to decide on what you consider to be the actual condition/dysfunction that the patient is presenting with. It is very common for an examiner during a consultation to ask a patient where their pain is. Suppose, in the particular case of assessing the pelvis, the patient points to the area inferior and medial to the PSIS (Figure 11.1(a)), and is able to do this consistently twice and also within a radius of 0.4” (1cm) each time; according to Fortin and Falco (1997), this is a positive sign of SIJ dysfunction.

Figure 11.1. (a) The Fortin finger test, as demonstrated by the patient pointing to the area of pain.

The above is an example of what is commonly called the Fortin finger test; I consider this test to be of value, but only in combination with the provocation tests described below, especially the FABER (Patrick’s) test.

Schamberger (2013) mentions that localized pain may arise from one or both SIJs: those with hypomobility or “locking” of one SIJ not infrequently complain of pain from the region of the other, supposedly “normal,” SIJ. One explanation for this pain is the increased stress placed on this “normal” joint and its capsule and ligaments as it tries to compensate for the lack of mobility of the impaired SIJ.

In the 1997 study, the Fortin finger test was used as a means of identifying patients with lower back pain and SIJ dysfunction. Provocation-positive SIJ injections were used to confirm or discount the applicability of this clinical sign for the identification of patients with SIJ dysfunction. A total of 16 subjects were chosen from 54 consecutive patients by using the Fortin finger test. All 16 patients subsequently had provocation-positive joint injections, validating SIJ abnormalities. These results indicate that a positive finding of the Fortin finger test, a simple diagnostic measure, successfully identifies patients with SIJ dysfunction.

Fortin et al. (1994) carried out an earlier study on pain pattern mapping for the SIJ and injected the contrast material Xylocaine into the actual SIJ in 10 volunteers. These authors reported that their sensory examination immediately after the injection revealed an area of buttock hypoesthesia extending approximately 4” (10cm) caudally (inferiorly) and 1.2” (3cm) laterally to the PSIS, as shown in Figure 11.1(b). This area of hypoesthesia corresponded to the area of maximal pain noted upon administration of the injection.

Figure 11.1. (b) The referral pattern of the SIJ from Fortin et al.’s 1994 study.

In terms of SIJ referral patterns, however, there has been a lot of debate about the exact location to which the SIJ refers: Fortin said 4” (10cm) caudally by 1.2” (3cm) laterally to the PSIS. In contrast, a study conducted by Slipman et al. (2000) called “Sacroiliac joint pain referral zones” recorded significant differences from Fortin’s findings. Using fifty consecutive patients who satisfied clinical criteria and demonstrated a positive diagnostic response to a fluoroscopically guided SIJ injection, Slipman’s study yielded the following results. Forty-seven patients (94.0%) described buttock pain, and thirty-six (72.0%) described lower lumbar pain. Twenty-five patients (50.0%) described associated lower-extremity pain. Fourteen patients (28.0%) described leg pain distal to the knee, groin pain was described in seven patients (14.0%), and six patients (12.0%) reported foot pain. Eighteen patterns of pain referral were observed. A statistically significant relationship was identified between pain location and age, with younger patients more likely to describe pain distal to the knee. It was concluded that pain referral from the SIJ does not appear to be limited to the lumbar region and buttock.

SIJ Provocative/Screening Tests

Based on very rigorously reviewed research, there are numerous ways of screening the SIJ. I, however, currently utilize only five of these provocation tests—those which I consider to be of real value to the clinician and which are used on a day-to-day basis throughout the UK (and the rest of the world) to commonly diagnose SIJ disorders. These SIJ provocation tests, when used in combination rather than in isolation, can be very accurate, as the feedback response from the SIJ can be very sensitive and specific, especially when giving information about the potential effectiveness of an SIJ dysfunction. These tests are not all specific in their application to the SIJ, because they also stress the hip joint and the lumbosacral region. Compressive types of testing motion are more likely to ascertain pain directly from within the joint, whereas distraction types of testing will provoke pain from the corresponding ligaments and joint capsule.

The presence of an SIJ dysfunction can be assumed if one achieves three out of five positive results with the following tests:

1. FABER

2. Compression

3. Thigh thrust

4. Distraction

5. Gaenslen

1. FABER Test

You may recall that I discussed the FABER (flexion, abduction, external rotation) test in Chapter 7, as it is commonly used to screen for any underlying hip pathology; however, it is also a very effective test for ascertaining SIJ dysfunction. The main reason why this test can help the therapist identify the presence of an SIJ dysfunction is the fact that the test induces a motion of the innominate bone in a posterior and external direction relative to the sacrum; this innominate motion encourages sacral nutation and subsequently stresses the associated ligaments (sacrotuberous, sacrospinous, and interosseous). The posteriorly rotated innominate position also becomes a lever that can be used to compress the SIJ posteriorly and open the joint anteriorly, which will then stretch the anterior capsule and associated ligaments.

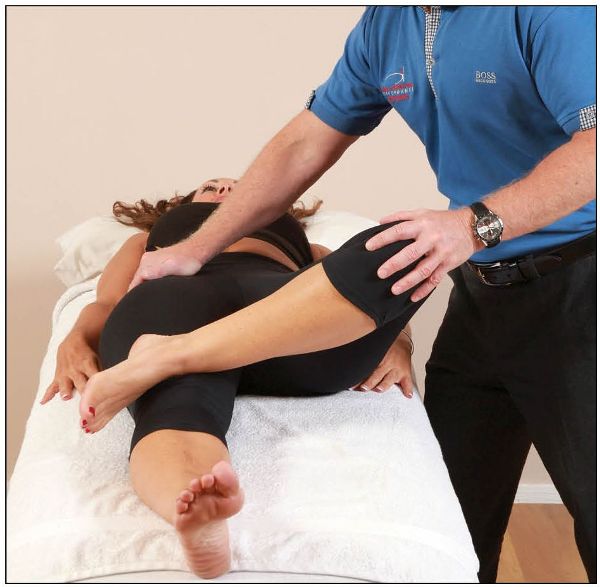

The therapist places the patient’s hip into a position of flexion, abduction, and external rotation. The opposite side of the pelvis (at the ASIS) is stabilized, and a gentle, steadily increasing pressure is applied to the same-side knee of the patient, exaggerating the motion of hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation, as shown in Figure 11.2. If there is a restriction (in the hip joint mainly) or pain posteriorly in the area of the SIJ, a pathological change/dysfunction within the SIJ might be indicated.

Figure 11.2. FABER test to screen for SIJ dysfunction.

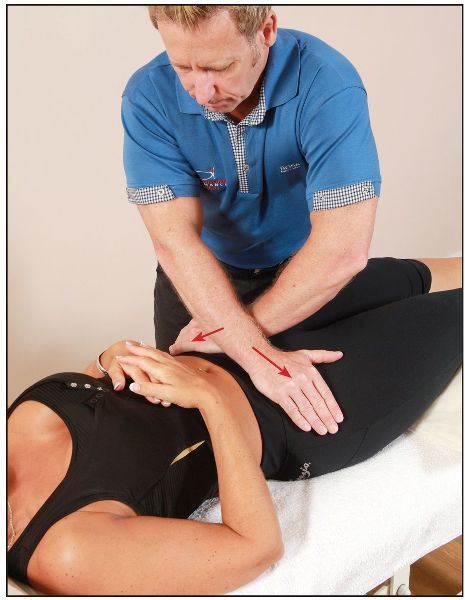

2. Compression Test

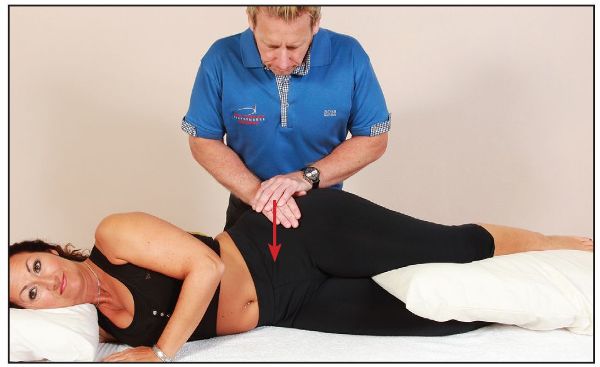

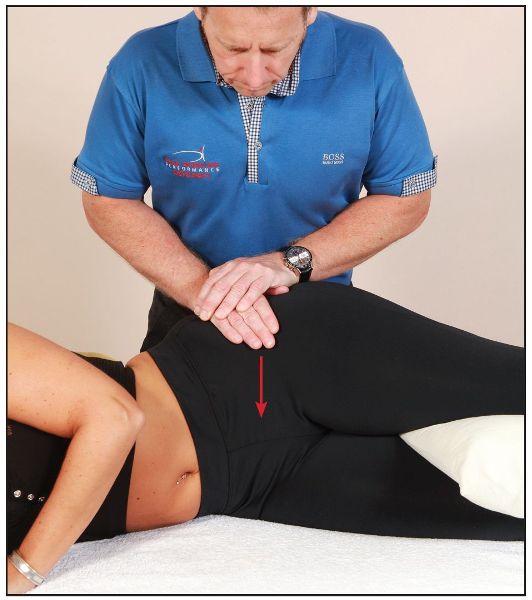

The patient is placed in a side-lying position, facing away from the therapist, with a pillow between the knees for comfort. The therapist applies a gradual downward pressure through the anterior aspect of the innominate, between the greater trochanter of the femur and the iliac crest, to check if pain in the corresponding SIJ is present, as shown in Figure 11.3(a–b).

Figure 11.3. (a) Compression test to screen for SIJ dysfunction.

Figure 11.3. (b) Close-up view of the compression test.

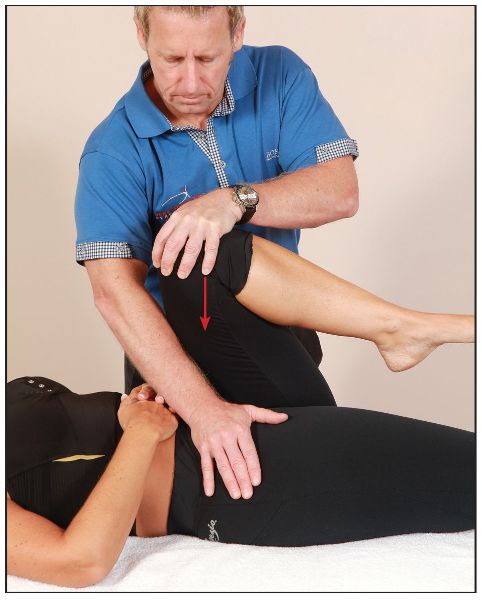

3. Thigh Thrust Test

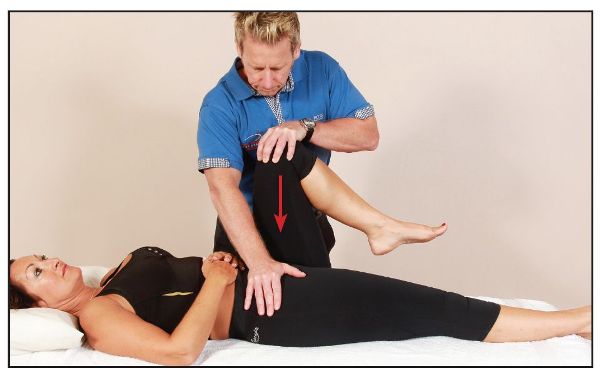

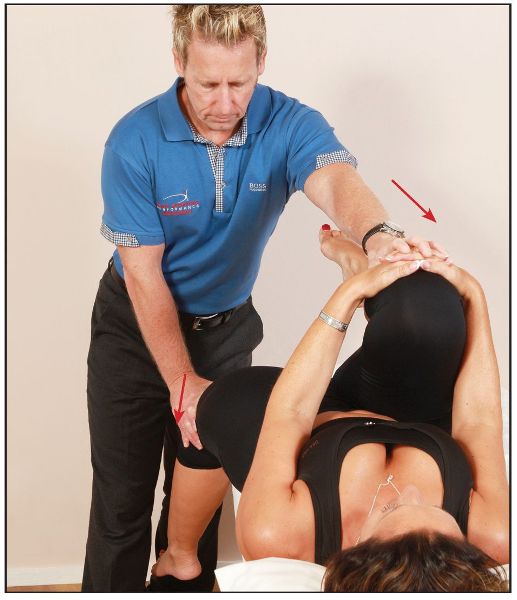

The patient lies in a supine position with one hip flexed to 90 degrees. The therapist stands on the same side as the flexed leg and stabilizes the patient’s pelvis by applying pressure to the opposite ASIS. Gradually increasing pressure is then applied through the axis of the femur, to determine if pain is present within the SIJ, as shown in Figure 11.4(a–b).

Figure 11.4. (a) Thigh thrust test to screen for SIJ dysfunction.

Figure 11.4. (b) Close-up view of the thigh thrust test.

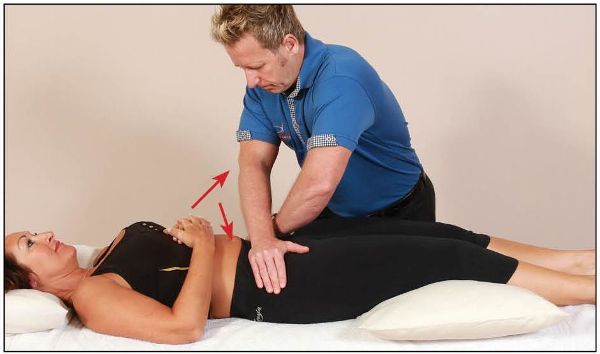

4. Distraction Test

The patient lies in a supine position with a pillow under their knees for support. With arms crossed and elbows relatively straight, the therapist places their hands on the anterior aspects of the patient’s left and right ASISs of the innominate bones. A gradual pressure is then applied laterally, to encourage a distraction of the SIJ, as shown in Figure 11.5(a–b). The presence of any pain is noted.

Figure 11.5. (a) Distraction test to screen for SIJ dysfunction.

Figure 11.5. (b) Close-up view of the distraction test.

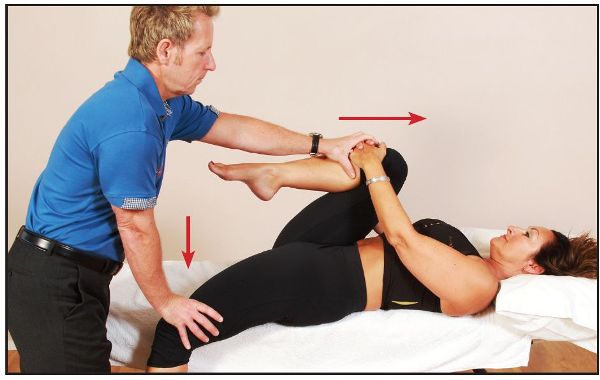

5. Gaenslen Test

The patient lies in a supine position near the left edge of the couch. They are asked to flex the right hip by pulling their right knee to their chest, a movement which rotates the right innominate posteriorly, while allowing the left innominate to rotate anteriorly; this particular action has the effect of locking the SIJ at the same time. The therapist slides the left lower leg off the couch and applies a gradual extension force to the already extended left leg, while simultaneously applying (through the patient’s hands) a flexion force through the right leg, as shown in Figure 11.6(a–b).

Figure 11.6. (a) Gaenslen test to screen for SIJ dysfunction.

Figure 11.6. (b) Close-up view of the Gaenslen test.