5.2 The field of intermediary organizations for school years abroad

As we saw in Chapter 3, school years abroad can take two different forms – either as part of a student exchange program or in the form of a boarding school stay abroad. Both types of school years abroad are organized by different types of organizations that we simply refer to as “student exchange organizations” and as “boarding school agencies” and that make up the field of suppliers of long-term school-related stays abroad. Student exchange organizations come in different sizes and different organizational forms: some are nonprofit while others are for-profit. Some operate only in Germany, while others operate internationally, as part of a global company or as part of an international network (Weichbrodt, 2014b). As we have already stated, in the programs offered by these organizations, students enroll in a school abroad for a period of time, regularly attend classes there, meet students from one or more other countries, and then usually return to their school in their home country.

One can distinguish this type of organization from the boarding school agencies – that is, organizations that organize boarding school stays only in non-German speaking countries and facilitate the acquisition of transnational human capital in this manner.1 The duration of a boarding school stay abroad is between one and three terms, but it may extend to a two-year stay, including a school-leaving qualification – for example, the International Baccalaureate or the relevant national school-leaving certificate (“A Levels” in the UK) – which then entitles the holder to enter higher education.

Both types of organizations have a monopoly in the transmission of transnational human capital in the form of a school year abroad. Since organizing a school year abroad requires a lot of organization and time, and because parents often lack foreign contacts, the vast majority do not organize a stay abroad themselves. Michael Weichbrodt (2014b, p. 83) estimates that in Germany about 95 percent of student exchanges are handled by specialist organizations (there is no data for boarding school agencies).

In the first step, we will briefly describe the historical development of the field of exchange organizations in Germany, and will then focus in the second step on its current structure and internal differentiation. We understand the field of exchange organizations as a subfield within a broader educational field. The basis for our discussion is – in addition to the relevant research literature, and in particular the study by Michael Weichbrodt (2014a; 2014b) – our own two primary research inquiries. First, we have created a dataset containing specific information on all the organizations in existence at the end of 2014. These data include, for example, the founding year, the size of the organization, the legal form, the types of programs offered by the organization, the number of students placed per year, the cost of studying abroad, and the number of destination countries. Second, we carried out expert interviews with employees of 13 organizations in order to gain information about the organization in question and its perception of the field as well as to reconstruct the application and selection processes used by organizations (for more details see the appendix).

The historical development of the provider field

The development of the field of provider organizations can be divided into two phases: the first phase covers the period from 1945 until the early 1980s, in which the field emerged in Germany owing to the particular historical context. The second phase runs from the early 1980s to the present day and is characterized by a substantial expansion of the field as well as increasing diversification.

Contextual conditions and structural features of the developing field after 1945

Although the beginnings of international youth exchange in Germany can be traced back to the beginning of the twentieth century and some organizations that still exist today were founded in the interwar period (Krüger-Potratz, 1996; Weichbrodt, 2014b), the actual development of this field started only after World War II and was shaped by the new international political order. This was the period in which the stage was set for the emergence of a bipolar world order and the so-called Cold War, which eventually resulted in two different social systems confronting each other in Europe until 1989: the democratic, capitalist market economies led by the United States on one side and the socialist party systems with a planned economy under the leadership of the USSR on the other side. In this process, the Federal Republic of Germany, which emerged from the American, British, and French occupation zones in 1949, was increasingly integrated in the political, economic, and military alliances of the West after the war. The Marshall Plan launched by the US government for the reconstruction of war-torn Europe did cover all Western European societies, but it was mainly Germany that benefited from it, which strengthened its ties to the United States. The introduction of English as a second language in German schools at that time, which was not least due to the fact that about two-thirds of the German population lived in the American and British zones (Garcia, 2015, p. 48), is likely to have contributed to the integration of the Federal Republic of Germany in the West. In 1951, the Federal Republic of Germany was one of the founding members of the European Coal and Steel Community, the forerunner of today’s European Union, and in 1955 it became a member of the Western defense alliance NATO.

This policy of integrating the Federal Republic of Germany in the West under the supremacy of the United States included the Allies’ programs for a “reeducation” or “reorientation” of the German population (Kellermann, 1981; Füssl, 1994; Latzin, 2005). Educational measures such as these had the goal of transmitting democratic attitudes and values to postwar German society. It was in this context that exchange programs that allowed students to go on a stay abroad for a period of six months to one year were established. These exchange programs – in line with the general educational objectives of the Allies – intended to provide the participants with an insight into a democratic culture and society, to teach them the associated values, and hence to bring these values to bear on postwar German society. In this way, exchange programs were intended to generally contribute to tolerance, understanding, and peace.

Given that the West German educational system was largely state-organized, one might have expected that this task would also have been taken over by the public educational institutions. But this did not occur and it still has not occurred. Instead, a subfield of non-state organizations emerged, which took on this task. Up to 1970, there were four such organizations: the American Field Service (AFS, today: AFS Interkulturelle Begegnungen e.V.), Experiment e.V., the Rotary Jugenddienst Deutschland e.V., and the Deutsche Youth For Understanding Komitee e.V. (YFU) (Weichbrodt, 2014b, pp. 80–81). During this phase, the provider field was thus shaped by organizations that mainly sent students to the United States, which were pursuing sociopolitical aims with their exchanges, and which operated on a nonprofit basis.

This course-setting period for the emerging field of exchange organizations subsequently led to a path dependency and continues to influence the structure of the field up to the present day:

(1) Stays abroad come at considerable cost for students and parents, a feature which (due to the almost complete elimination of previous tuition fees) is rather atypical for the German education system, and which substantially limits access opportunities for young people from families that do not have sufficient incomes or assets (see Chapter 3).

(2) The embedding of this emerging field in the larger context of the US-led Western integration of the Federal Republic of Germany meant that student exchanges took place primarily in the United States. Hence, from the outset, the United States was by far the most important destination for school exchanges. This prominent position is also reflected in the establishment of the “Congress Bundestag Youth Exchange” program by the US Congress and the German Bundestag in 1983, one of the few public scholarship programs in the field of student exchanges (in German: “Parlamentarisches Patenschafts-Programm”).

(3) At the same time, in connection with the “reeducation” programs, we see an institutionalization of a specific form of illusio on the part of organizations, which motivates and legitimizes their actions: student exchange programs aim to promote intercultural exchange, contribute to international understanding, and thus help to prevent conflicts between nations in the long term. Even today, these objectives are evident in the self-presentation of the nonprofit organizations that have been active in Germany since the postwar period. So, for example, YFU presents itself on its website as follows:

Together with YFU organizations in our 50 partner countries, our association stands for intercultural awareness, education in democratic citizenship, and social responsibility by offering young people the opportunity to experience a different culture as a member of a host family and to gain new perspectives.

(Deutsches Youth For Understanding Komitee, 2015, own translation from the original German-language website)

And the Rotary Jugenddienst says about itself,

With our exchange programs, the Rotarians want to contribute to cultural exchange and thus to understanding between peoples and peace. The objectives are to learn about other ways of living and gain deeper experience of another culture, as well as more generally extending the individual’s own perspective and developing one’s personality.

(Rotary Jugenddienst Deutschland, 2015, own translation from the original German-language website)

However, this illusio makes it easy to overlook the fact that even if these organizations are nonprofit, they are always also pursuing a market-based interest because they finance themselves by placing students abroad. Although profit maximization is not an organizational goal for nonprofit providers, they can fund their work only if their services are in demand among paying customers. Because this field of providers is organized in the form of a market, the interactions that take place in it are also economically motivated. As we will show in the following, a tension emerges within all organizations in this field between their market orientations on the one hand and on the other hand the objectives of the programs and orientations of the employees, which are shaped by the illusio.

Expansion, marketization, and diversification of the field since the 1980s

In the 1980s and 1990s, the outlined field structure began to change. A decisive factor influencing this was certainly the significant growth in demand for stays abroad, as we have described in detail in Chapter 2. Between 1950 and 1980, there was only a very slight increase in the number of students who had gone abroad with a student exchange program. In the period from 1980 to 2010, the number of these exchanges increased from an estimated 1,300 to 19,000, which represents a fifteen-fold increase in a relatively short period of time (Weichbrodt, 2014a, p. 29). In addition, there are German students who do not go abroad via an exchange program, but who attend a boarding school abroad. As explained in Chapter 3, the number of boarding school students has also increased over time.

In Chapter 2, we explained this exponential growth in the number of students who go abroad for a year with reference to changes in three contextual factors: the growth in the value of transnational human capital due to an increased demand for these skills in the labor market (triggered by processes of globalization), the increase in the symbolic value of transnational human capital due to a redefinition of what a good education and good professional qualifications involve, and finally, the increasing need of the middle and upper classes for distinction in response to the devaluation of educational qualifications due to educational expansion. The exchange organizations are themselves involved in the creation of this demand as they belong to the field of organizations that define transnational competences as important and have hence contributed significantly to the social redefinition of educational and professional qualifications. As a result of these three changes and the exponential increase in demand for the year abroad that this has triggered, we can observe an expansion and change in the provider field in the following dimensions since the 1980s:

(1) From the outset, the provider field was especially shaped by non-state organizations. Little has changed in this respect over the course of subsequent developments; although state educational institutions do offer their students the opportunity to go abroad temporarily in the context of school partnerships or specific exchange programs, this is usually limited to more short-term stays abroad. But these state-run organizations are still not required to provide the same kinds of services as the non-state organizations.

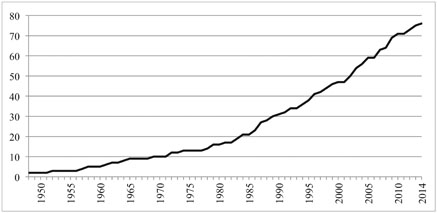

(2) The expansion of the demand for a stay abroad did not prompt an expansion in the few existing organizations that were there to cater to this demand; instead, it led to the founding of new organizations, mainly in the private sector, which saw a new market opportunity for themselves (see Figure 5.1). Often these are spin-offs founded by employees from existing organizations that use their contacts to start their own businesses. The number of student exchange organizations in Germany rose over time to about 78 organizations in 2014.2

Figure 5.1 Number of exchange organizations: 1948–2014

Source: Own research and presentation; without providers of only private schools.

(3) While until about 1980, nonprofit organizations determined the market of exchange organizations alone, private, for-profit companies increasingly entered the field in this second phase of development; today, they are even in the majority (Weichbrodt, 2014b, p. 81). This shift is also evident when looking at the four largest providers of student exchange programs then and now (based on the number of students who went abroad): while until the 1970s, the field was dominated by the four nonprofit organizations that had started student exchanges in Germany in the postwar period (i.e., AFS, Experiment, the Rotary Jugenddienst, and YFU), there are now two nonprofit organizations – namely, AFS and YFU – and two private-sector organizations, EF Education (Germany) GmbH (EF) and iSt Internationale Sprach- und Studienreisen GmbH (iSt) (Weichbrodt, 2014b, pp. 81–83).3 At present, 17 of the 78 student exchange organizations are currently nonprofit, a share of 22 percent, while the remaining 78 percent are privately organized.

(4) The entry of private-sector organizations into the provider field has also been accompanied by a shift in the goals linked to a stay abroad. Although all providers share the overall illusio that a stay abroad has positive effects, two poles have emerged within the field regarding what kind of effect is more important: the already established nonprofit student exchange organizations, with their emphasis on the added societal value of their work and the idea of intercultural exchange, international understanding, and peace represent the orthodox pole of the field here. In contrast, the private companies that have established themselves in the market have challenged this view by focusing on the individual benefits of their programs for the students who participate. They point in particular to the language skills needed in a globalized world, stress the importance of studying abroad for personal development, and refer to the fun that this experience can provide. They thus represent the heterodox pole in the field. In line with this, the private-sector organization Stepin advertises its student exchange programs on its website as follows:

If you are open and can get excited by new ideas, a stay abroad is a time full of opportunities. You won’t just learn another language perfectly, but also experience another country with its people and cultural characteristics in all its facets. The experiences you have at a school abroad will stay with you for the rest of your life. And in addition to the fun, there is also the advantage that you will have in your working life later on due to the time spent at a high school abroad. That’s because foreign languages and so-called intercultural skills are high up on the list of things companies expect from their future employees today. And playing American football or being a cheerleader also has its own charm, right?

(Stepin, 2015, own translation from the original German-language website)

The emphasis on the individual benefits, particularly aspects such as the personal development and the “fun factor,” in connection with stays abroad can thereby also be interpreted as a response to the clearly discernable change in values since the 1970s, through which self-realization values and hedonistic attitudes have gained more importance (Inglehart, 1990). By referring to these changing value systems, the private-sector organizations are creating a space for themselves to adopt a positioning that is in opposition to the established organizations and to challenge the hitherto dominant definition of what is at stake in the game within the field, as Bourdieu would call it.

In line with the two different manifestations of the field-specific illusio and the emergence of the opposite ideological poles in the field, the two types of organizations differ (up to the present) in how they perceive and describe the area in which they operate. While private organizations describe the field as a market in which one can compete with other providers in a much more self-evident way, the nonprofits tend to reject the idea of a market and also do not see themselves as mere service providers to the families.

(5) As the number of providers increased in total, and especially as the number of private providers increased, there was a simultaneous diversification of their programs. Thus, the number of potential host countries from which young people and families could choose increased, although this expansion mainly pertained to other English-speaking countries (Great Britain, Canada, Australia, New Zealand), but also to individual Western European and Latin American countries. After 1990, some providers also added Eastern European and Asian countries as destination countries (Weichbrodt, 2014b, p. 81). Despite this diversification of countries offered, the United States remains by far the most important destination, even if the proportion of German exchange students going to other countries has increased in recent years (Weltweiser, 2014). This reveals a certain path dependence of the development, which is due to the early focus on the United States as a destination and which has persisted in the expansion phase of the field. In addition to an expansion of the countries that can be selected, parents or young people are also increasingly offered a variety of options in other program areas. In this vein, shorter-term programs were introduced (with a duration of three to six months); parents also have greater leeway now to choose the region within the destination country or, in the case of the United States or Canada, the state. Or there is the option to choose the school the child will attend; this also includes the choice between a private and a public school.

(6) This diversification of supply is directly connected to another feature that is important both for the development of the field and for inequality: the differentiation of prices for a stay abroad. Customers who do not want the default “standard menu” of an organization, but who want to have more say on the specific form the arrangement would take, have to dig deeper into their pockets. The different options are thus associated with significantly higher costs. The diversification of the range of available services is therefore linked to a widening of the range of prices for a stay abroad. For a student exchange program, these range from about €5,500 to €24,000 (Terbeck, 2012); a one-year stay at a boarding school abroad could cost €30,000 or more. It is clear that the generally more expensive choice programs can be afforded only by families with a good economic capital endowment. This reveals a homology between the social space and the social structural, especially economic, positioning of the families and the structure of this provider field. We will get back to this point in more detail in the following.

(7) There is another development related to the diversification of supply and the associated differentiation of prices: in addition to the student exchange organizations, a separate segment of organizations has emerged within the field, which exclusively specializes in arranging boarding school stays in non-German-speaking countries. The first such organization was founded in Germany in 1979, but the real development began only in the 1990s, when additional providers joined the field. The majority of the 18 or so boarding school agencies currently active in Germany were even founded after the turn of the millennium. Unlike the student exchange organizations, boarding school agencies are all purely private organizations; in addition, they are characterized by their specialization in a certain clientele, which has a high income and/or assets. We will present this segment in more detail ahead.

(8) These changes in the field of providers of student stays abroad, which are mainly due to the increase of private-sector organizations, have simultaneously changed competition in the field itself. The nonprofit organizations in particular are progressively being exposed to marketization pressures. For example, the organizations are increasingly faced with the question of whether to pay host families. This practice was actually rejected by the nonprofits because of their beliefs about the purpose of student exchanges. But other providers do offer such payments, which means it is a problem to find host families who are willing to take children for free. In addition, a diversification of services can be observed among the nonprofits, which can be interpreted as a consequence of the changing competitive situation. In line with this, stay abroad programs of a shorter duration or programs with optional extras have been introduced. The new market situation has also led some nonprofit organizations to change their application process so that they can approve candidates more quickly. As students or families are increasingly applying to several organizations simultaneously and are looking for a quick response, the speed of approval is now an important factor in the competition among organizations.

It is therefore hardly surprising that employees of the nonprofits we interviewed often described changes in the field as being “forced” or “pressured.” An employee (O6, 150) even stated that for many years, people did not want to speak of a “market” and that the organization did not want to be part of one; such an attitude would no longer be possible due to competition, in particular with “commercial” competitors. As a consequence of this development, the distinction between nonprofit and for-profit organizations, which has structured the field for a long time, is being blurred and is losing its potency.

The current structure of the provider field – the premium, choice, and basic segments

The dynamics of the development of the field that can be observed since the 1990s have led to the earlier described adaptation processes among student exchange organizations, and especially to a stronger assertion of a market logic in the field, which the formerly dominant nonprofit organizations cannot escape. In this respect, the opposition between the orthodox and heterodox pole that previously existed has been resolved to some extent, as the latter has gained dominance in the field. Despite this development, however, the differences between the various organizations continue to exist, at least in part. Having described the development of the field of organizations in Germany since 1945 in the last section, we now focus on describing the current internal structure of the field.

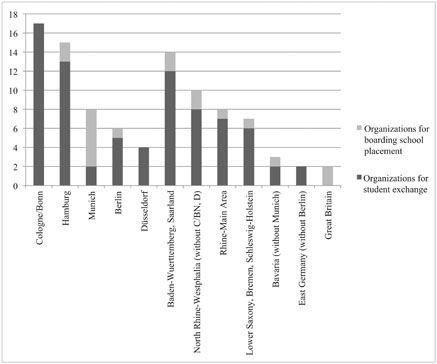

As mentioned earlier, the provider field currently consists of a total of about 78 student exchange organizations, of which nearly four-fifths are for-profit organizations and the rest are nonprofits, as well as 18 boarding school agencies. In regional terms, these organizations are very differentially distributed across Germany. While the boarding school agencies can be mainly found in affluent cities, such as Munich or Hamburg, or around such cities, one-half of the student exchange organizations are located in four metropolitan areas (Cologne/Bonn, Hamburg, Berlin, and Dusseldorf) and almost the entire other half are in the rest of the former West Germany; on the other hand, student exchange organizations are hardly present in East Germany (see Figure 5.2). Even if many organizations also have regional representatives, this reveals significant differences in the opportunity structure for a school year abroad (see Chapter 3).

Figure 5.2 Location of headquarters of exchange organizations operating in Germany (2014)

Source: Own research and presentation.

Here, we will discuss the internal structure of the provider field in more detail, distinguishing between three different segments. Table 5.1 summarizes the

Table 5.1 The social field of exchange organizations and its inner differentiation

| Premium segment | Choice segment | Basic segment | |

|

|

|||

| Product offered | Boarding school stays, optional diploma abroad | Student exchange | Student exchange |

| Legal form | Private | Mainly private (share of nonprofit: 16%) | Nonprofit or private (share of nonprofit: 50%) |

| Historical development | Since the mid-1990s, average founding year: 2001 | Expansion since the early 1980s, average founding year: 1994 | Since postwar period, average founding year: 1975 |

| Size of organization | Varying | Varying | Small |

| Range of programs | Highly individualized offers (within the spectrum of boarding schools) | Basic program and additional options | Basic program only |

| Price level of offered products | High | Varying (relatively low to medium) | Relatively low |

| Social class and economic capital of customers | Wealthy, high amount of economic capital | Varying (upper to lower middle class) | Limited (mostly lower middle class) |

| Acquisition of participants/customers | Relatively exclusive, mainly through personal recommendation and individual counseling | Less exclusive, a wider range of “recruiting channels” is used | |

| Selection and placing procedures | Highly flexible and customer-oriented procedures | Largely standardized procedures, medium flexibility, and less individualized approach | Largely standardized procedures, low flexibility, and less individualized approach |

| Requirements for participation | None (if payment is guaranteed) | Similar to the basic segment, but less strict (at extra charge) | School grades, no health or behavioral problems, for nonprofits: students should not exhibit an attitude of consumerism towards their stay abroad |

| Illusio (program’s main ideological goal) | Solely emphasizing individual educational and capital development | Individual educational development and special leisure experiences are emphasized over cultural exchange/getting to know other cultures | Cultural exchange/getting to know other cultures is prioritized over individual educational development |

descriptions of the segments according to various dimensions. We will see that the internal differentiation of the field can be interpreted as a homology between the social structural positioning of the families in the social space on the one hand (especially with regard to their economic capital) and the various segments of the provider field on the other hand. First, there is a premium segment, which focuses on placing students in expensive boarding schools; the clientele of these organizations is mainly families with very high incomes and/or assets, which means that when comparing the three segments, we should find the highest levels of social selectivity here. The second field segment, the so-called choice segment, is characterized by the fact that both programs with and without additional options are offered. This results in a spread in the prices for these programs, which in turn allows customers with different economic capital positions to request particular services from these providers. The third and last segment is called the basic segment, which offers students the opportunity to participate in exchange programs at comparatively low prices (i.e., relative to the prices in the other two segments). With respect to the class position of the customers, this means that the families whose economic capital is comparatively low are likely to be found in this segment.

The premium segment

In the field of providers of stays abroad, the boarding school agencies constitute a separate market segment, which we call the premium segment. In Germany, this segment consists of about 18 organizations, all of which are run as private, forprofit organizations. As we already explained in the previous section, the majority of boarding school agencies have come into being only since the 1990s – the average founding year is 2001; hence, this was at a time when the demand for educational stays abroad and thus the distinction needs of the middle and upper classes had risen sharply. All the organizations active in this segment are relatively small companies with about 15 or fewer employees.

The specialization of these organizations on boarding schools means that there is no direct competition with the providers of student exchange programs. Even within the segment, despite the underlying competition for customers, there seems to be a certain division of the market. This reveals itself, on the one hand, with regard to the clientele – one organization appears to have particularly specialized in placing members of the aristocracy in boarding schools – and on the other hand, with regard to the host countries offered. Some agencies deal primarily with the UK, while others specialize in Australia, Canada, and the United States.

The delimitation of the premium segment from the other two segments is manifested not only in the specialization in boarding school placement but also in the price that parents have to pay for a stay abroad. And that price in turn structures the specific clientele and their class position, the form of client acquisition, the procedures that are used when placing students, and the demands that are placed on the students. This reveals a significant homology between the class position of the families in the social space that use the services of a boarding school agency and the orientation and positioning of these organizations within the provider field.

As mentioned earlier, a one-year stay abroad at a boarding school usually costs at least €30,000 and from there on there is almost no upper limit. There are also additional costs that arise because the school year in many boarding schools is divided into trimesters – especially in the UK. Between these trimesters, boarding schools are closed and the students have to travel back to their parents in Germany. For this reason, the families who use boarding school agencies usually have a high income or assets – that is, high economic capital. Given the product these organizations offer and the relatively high price associated with it, it is also fitting that the 18 boarding school agencies are typically located, as we have seen, in very wealthy German metropolitan areas and thus nearby a wealthy clientele.

Unlike the student exchange organizations, which will be addressed in more detail in the following two sections, the boarding school agencies are paid for their work not primarily by the parents but by the foreign boarding schools: when the child has been accepted by the school and the parents have paid the school fees, the organization receives a commission from the school. The boarding school agencies thus act as a broker between the foreign schools and families in the home country. The organizations receive only a relatively low fee of €200 to €300 from the families for their consulting and placement services, regardless of whether the child is accepted by the school.

The form of customer acquisition also clearly marks out the boarding school agencies from the other organizations. This includes, first, the fact that these organizations prefer to locate their operations in wealthy cities or regions. Second, this pertains to their specific web presences; their websites typically include pictures of a venerable boarding school and of students in their school uniforms or pursuing artistic or sporting activities. These representations symbolize prosperity, historical connection, solidity, and dependability. Likewise, the photographs of employees found on some boarding school websites exude a certain poise and trustworthiness. These websites sometimes also mention the noble titles or prestigious educational qualifications held by the organization’s key staff members, which lends the organization additional symbolic grace. Prospective clients who look at these sites know with a single click whether they have found the right organization for them. In a sense, the symbolic self-representations of these providers document the social class position of the clientele the organization seeks to address.

Third, for boarding school agencies the form of client acquisition they rely on typically involves parents contacting the organization “by themselves” and on the basis of personal recommendations. According to the organizations we interviewed, 50 percent to 60 percent of the parents say that they chose the organization based on a personal recommendation. It can be assumed that the clients from the affluent social classes are well connected among themselves, that they exchange experiences with each other, and that they use this social capital to get into contact with a boarding school agency. The high importance of personal recommendations in client acquisition also allows boarding school agencies (unlike the student exchange organizations) to skip major events such as education fairs. Their chances of meeting the clientele they seek to attract at such events are rather small. Working with schools (to distribute information or hold awareness-raising events) also does not play a role in attracting customers. What are more signifi-cant, however, are advisory days in different cities – typically held in cities where their wealthy clientele lives, such as Munich, Dusseldorf, Hamburg, or Berlin – in which the organizations set up individual meetings of up to one hour with families about the possibility of a boarding school stay abroad. This represents a significantly more individual form of customer acquisition than is the case for the other two segments in the field.

Furthermore, the boarding school agency segment differs from the other two segments due to the particular nature of the placement process. This is characterized by an individualization of the service offered and a very high degree of flexibility in the process, and it involves an “à la carte” approach tailored to the individual needs of the customers. This becomes clear when the placement process is looked at in detail. After receiving a short application, in which the families or the child provide the most important information about themselves, there is a consultation with the parents and the student. Bearing in mind the family’s ideas and preferences, the child’s academic performance, and his or her athletic abilities, artistic skills, or other interests on the one hand, and on the basis of knowledge about the various boarding schools on the other hand, the organization will compile a list of “suitable” boarding schools.

A special feature of these consultations is that the question of the intrinsic motivation of the child to go abroad plays a relatively minor role. As we will see, this distinguishes providers in the premium segment significantly from those of the other two segments. Here, motivation is not a precondition for a stay abroad but something that can be awakened or amplified by the parents, and by the staff of the boarding school agency.4 In this respect, the motivation of the child is less an exclusion criterion, but is merely something that is of interest to the boarding school agency when seeking to create a “match” between the boarding school and the child. The question of the price of a boarding school stay also does not seem to play a particularly significant role in these advisory sessions. It is assumed at this point of the placement process that families can pay the price. If requested, the length of the stay abroad can be limited to one or two terms to reduce the costs, but given the price range of the services in this segment, the essential selection of potential customers can be expected to have occurred in advance. This also fits with the fact that boarding school agencies do not themselves offer (partial) scholarships or provide much information about external funding opportunities in these advisory sessions.

After the consultation, the organization generally recommends three to eight boarding schools, which the family then usually narrows down to two to four. If the stay abroad is intended to take place in the UK, parents and students usually travel there to gather impressions, so that they can then decide on a particular school, at which the child must once again apply. The families thus have a relatively high degree of freedom in decision-making and plenty of opportunities to make their own requests, which is not the case with the programs offered by the student exchange organizations.

The particular character of the placement process, which differentiates boarding school agencies from other organizations, is also reflected in its temporal flexibility. Unlike with student exchange organizations, there are no rigid time limits by which an application has to be sent to the organization. Even if, as stated by our interviewees, most families come to the organization approximately one year in advance, there is usually still a not-insignificant number of families who contact the organization only a half a year or even a few months before the school year abroad starts. It might not be possible to send the child to all the boarding schools the organization is in contact with, but according to our interviewees, the supply of boarding schools is always large enough to still find a place.

But that is not the only reason boarding school agencies seem to be able to place almost every student. Even the candidates’ school grades and other personal characteristics play only a minor role as selection criteria. This may seem surprising at first glance, because it is precisely the British boarding schools that enjoy an elitist aura with high selectivity. But this public image is only the tip of the iceberg. With regard to the level of academic achievement, the British boarding school sector also has a high level of internal differentiation. Hence, according to the organizations we interviewed, it is always possible to find an appropriate school for all applicants, even if the boarding school agencies offer no official guarantee to the families. The service of the organization is merely the placement of the student at one of the listed boarding schools: whether the child is actually accepted is up to the school itself. But because the boarding school agencies select the possible schools based on the child’s interests and academic abilities and their knowledge of the internal differentiation of the overseas boarding school sector, acceptance at one of the schools listed is at least very likely. Access to boarding schools abroad therefore seems not to be so dependent on the institutionalized educational capital of the students, but on the material capital of the parents, which constitutes the decisive door opener for the children.

A final aspect that is constitutive of the boarding school agencies relates to the specific form the illusio takes in this segment compared to the other two. In this regard, we have seen that the various organizations move between two poles in the field. The boarding school agencies can be clearly assigned to the heterodox pole: the idea of intercultural exchange, international understanding, and the promotion of peace does not matter much in the premium segment. Instead, the boarding school agencies emphasize the individual benefits that attending a boarding school abroad may bring. They see themselves as “consultants” in the development of the individual’s educational biography. In the advisory sessions, they consider the child’s educational career to date, take the further school career and possible university intentions on board, and work out a proposal on the basis of their knowledge of the boarding school landscape that precisely meets the further development needs of the child.

The choice segment

While the premium segment relatively clearly differs from the other two segments due to its specialization in boarding schools and the high price connected to a boarding school, the differences between the choice and the basic segments are much lower. The main difference between these two segments is expressed in the name we have chosen: the organizations in the choice segment offer families more opportunities to select what they want, while the basic segment providers rather offer a standardized and unalterable “total package.” This difference also goes hand in hand with other features that make both segments distinct (see Table 5.1).

Sixty-four of the 78 student exchange organizations that specialize in arranging exchange years can be assigned to the choice segment, corresponding to a share of 82 percent. While all the suppliers in the premium segment are private organizations, we see a mixed structure in the choice segment, although the proportion of the commercial organizations is clearly higher: 84 percent are commercial and 16 percent are nonprofit. In terms of organization size, in the choice segment we see both larger organizations that place over 1,000 students per year (e.g., EF and iSt), as well as smaller organizations that place less than 100 students per year. Similar to the suppliers in the premium segment, the majority of providers in the choice segment started during the period of expansion when demand for stays abroad increased – 1994 is the average founding year.

A constitutive feature of the organizations in the choice segment that clearly distinguishes them from those of the basic segment is the options that they offer to families. These primarily consist of the following options: (a) the possibility to choose within a country – for example, in the United States – a specific state, (b) the option to define the region within a country where the child should attend school, and (c) the option to select a private rather than a public school, or to select a particular school for the child. Some of the organizations provide only one of these options, while others provide two or even all three. If families do not select any of these options, they effectively get the standard program, which is why the programs in the choice segment partially overlap with those in the basic segment.

The options offered are, however, not free of charge. When families select one of these options, the total cost of the stay abroad of the child also increases. The price range lies – depending on the country and specific program and without considering pocket money – between approximately €5,500 and €24,000 (Terbeck, 2012). By selecting one or more program options, the price increases significantly compared to the basic program. An example from the United States program offered by Intrax: a one-year program at a US school beginning in the summer of a year usually costs €7,590 without any select options (as of December 1, 2014); if, on the other hand, a family wants to decide which region or city to select and which public or private school the child should attend, the program price increases to at least €17,790 (Intrax, 2015a; 2015b).

Given the different rates of the programs offered, it is to be expected that this will also affect the clientele attracted by the select programs. These clients must be endowed with sufficient economic capital to allow their children to participate in the select program. Since the providers in the choice segment also offer the cheaper standard programs, this segment should have a more heterogeneous client composition compared to the basic segment, ranging from the upper to the lower middle classes; at the same time, it should differ from the premium segment. In this vein, an employee of an exchange organization (O5, 57) in the choice segment said during the interview that the “elite” would rather go abroad with other, more exclusive organizations. Hence, similar to the premium segment, a certain homology is evident in the choice segment between the class positions of the clients and the supply structure.

The specific clientele of the choice segment in turn has an impact on how the organizations try to attract clients. Because this clientele is broader in its social structural composition, providers use multiple and less exclusive ways of acquiring customers than the organizations in the premium segment. While personal recommendations also play an important role in the choice and basic segment, they are only one way among others – in sharp contrast to the situation in the premium segment. In line with this, the organizations in these two segments are usually present at various youth or educational fairs, which take place several times a year in various German cities, to showcase their study abroad programs. In addition, providers try to distribute information materials at schools or to conduct information sessions or to recruit former program participants or parents as multipliers who will provide information about their organization’s programs at their schools. Finally, the broader and less exclusive form of customer recruitment in the choice and the basic segment is also evident in the wider geographical distribution of these providers. As shown before, this is – in contrast to the boarding school agencies – not as strongly focused on particularly prosperous cities or regions.

There are also clear differences between the premium segment and the choice and basic segments in how the application and placement processes are structured. As we have seen, the selection process has a very flexible approach in the premium segment and is tailored to the individual needs of customers. In the choice segment – and even more so in the basic segment – the procedure, however, is much more standardized and is characterized by a significantly higher rigidity. This is related to the predefined program structures, which provide only very limited design options beyond the aforementioned select options. The selection and placement processes usually operate such that the organizations initially get a short application, including initial information on the desired stay abroad (destination country, duration, etc.), on the participants themselves (name, gender, contact details, information on health – e.g., allergies), on his or her academic performance, and on the parents. Unlike the boarding school agencies, which can also organize a stay at a school abroad at relatively short notice if necessary, the student exchange organizations impose very strict deadlines for some target countries, which have to be complied with (mostly the organizations therefore recommend that the application process starts about a year in advance). For families, these deadlines mean they have less flexibility and have to make long-term plans if the child is to go abroad at a certain time in the course of his or her school career.

After the short application, the student exchange organizations usually invite the student and the family for an interview or seminar. The structure of these discussions ranges from structured group discussions to the use of scoring systems. Entirely standardized procedures do not seem to exist. Instead, despite all the standardized criteria, a central role in determining whether a student is accepted is also played by the intuitive assessment of the student by the organization’s employees and volunteers. Hence, in the interviews we conducted, the interviewees often referred to “common sense” or “gut feeling” in this context.

The stricter regulation and standardization of the selection and placement process in the choice segment and especially in the basic segment compared to the premium segment organizations are also reflected in the demands that are placed on the candidates (at least for the programs without select options). First, in both the choice and basic segments, a stronger focus is placed on the social behavior of candidates in the selection or placement discussions. Hence, by observing how they interact in the group of applicants or with their parents, the organization tries to assess how the candidates will behave abroad or in the host family. This criterion plays virtually no role for the providers in the premium segment. Second, in the discussions, attention is paid to whether the students show an intrinsic motivation and are not just following the insistence of the parents or copying their friends. If the students do not send the right signals in the interview, this is a possible reason for rejection. Third, to a much greater extent than is the case for the boarding school agencies, employees of student exchange programs point out to candidates and their families that they should have “realistic” expectations – as the expression frequently used in the interviews goes – for the school year abroad. So, for example, students and parents often have certain expectations regarding the specific destination, the opportunities to pursue certain hobbies and leisure activities, or the standard of living of the host family. These calls for “realistic” expectations show that in the selection process in these two segments it is less about establishing a fit between the family and the program (as is the case in the premium segment); instead, the focus is primarily on making applicants or families fit the existing program structures. However, this last point is less applicable to the choice segment than to the basic segment, since candidates in the choice segment have the option to select between different packages for an additional fee.

Within the selection process, the organizations in the basic and choice segment are in particular trying to avoid the inclusion of students who are perceived as “problematic.” Such an assessment occurs in cases with a combination of certain signals, which will make it more difficult for the child to be placed abroad or which will hinder the child in adapting to life abroad based on previous experience (allergies, poor academic performance, undesirable social behavior, signs of homesickness exceeding a “normal” level, parents who cannot “let go” of their child or are otherwise perceived as “difficult”). In practice, however, applicants are rarely refused. This may also be related to the fact that the organizations in those two segments (including the nonprofits) are financed by their customers and thus have a fundamental interest in concluding a contract. Based on our interviews, we also got the impression that this situation has become even more demanding over time, for the providers in both the basic and the choice segments. The competition between the student exchange organizations seems now to be so great that they can less afford to reject applicants. If there is the danger that prospects may “quit” for any reason whatsoever, the organizations try to retain them by making alternative offers (e.g., to attend a language school abroad, an au pair stay, “work and travel” programs, etc.).

Another point that distinguishes the basic and choice segments from the premium segment concerns the question of scholarships and advice on external funding opportunities to help families with the financing of a school year abroad where necessary. Unlike the boarding school agencies, this subject is of greater importance for the providers in the basic and choice segments, both in their external communications and in discussions with potential applicants. However, among the student exchange organizations there are great differences in terms of the range and the number of (partial) scholarships.5 In this regard, the choice and basic segments differ, since there appears to be hardly any scholarships for select programs.

With reference to the issue of scholarships, it is also noticeable that the award criteria for funding used by student exchange organizations (irrespective of their segmentation) appear to be rather inconsistent. Depending on the organization, the focus is sometimes on the financial need of the student or the family, sometimes on the social commitment, the impression the individual makes in person, or achievement in certain areas (sporting, artistic, or other “creative” areas) or it is a combination of these criteria. However, this also allows families who do not necessarily need a scholarship based on economic criteria to apply for a (partial) scholarship. Added to this is the fact that (partial) scholarships are sometimes available only for certain, less popular country programs in order to increase their attractiveness – that is, they are in place for marketing purposes or to regulate demand for particular countries within the organization.

The last point, which distinguishes the providers in the choice segment from those in the premium segment, but also from those in the basic segment, relates to the form of the illusio – that is, the question of what dominant ideological objectives they pursue with their programs. In this regard, we previously distinguished between two ideas that represent the poles of the field: on the one hand, the idea of intercultural exchange, understanding between peoples, and peace, which will be furthered by going abroad (orthodox pole), and on the other hand, the concept of promoting the individual advancement of the student (heterodox pole). The latter does not advance the collective good, but offers individual advantages for the student, be it a rather hedonistic version of having fun or an investment in the student’s educational and professional future.

While the premium segment emphasizes only the individual benefits of studying abroad for students, the organizations of the choice segment have a hybrid position regarding these two poles. Besides the individual benefits, some of these organizations also focus on aspects such as improving understanding between people of different origins and bringing tolerance, as the following example from the GIVE Gesellschaft für Internationale Verständigung mbH shows:

For many years, we have been committed to student exchanges in the context of international understanding. With us, you will gain a deep insight into the culture and lifestyle of the people in the United States, Canada, New Zealand, Australia, or England. Of course, our students acquire excellent language skills in high schools abroad and in the host families.

(GIVE, 2015, own translation from the original German-language website)

Other organizations in the choice segment more strongly emphasize the individual benefits that a stay abroad can bring for students. This is illustrated by a sample quote from Kaplan International, in which the investment aspect becomes clear:

For 20 years we have supported students in realizing their dreams of a student exchange. Attending a school abroad for an extended period of time will enrich you in many ways – you will have valuable experiences that you will never have again. A high-school stay offers you a unique opportunity to immerse yourself in the culture of another country and is a plus for your school career and your future life!

(Kaplan International, 2015, own translation from the original German-language website)

But fundamentally, regardless of whether they emphasize the societal or individual benefits of their programs, the organizations in the choice segment follow the general illusio of the field, which is expressed in the idea of using one’s work to do something positive. The fact that, in spite of the selection procedure, they manage to place almost every student, does not contradict this, but points to the effects of the different action orientations of the organizations – on the one hand, the pursuit of certain goals and, on the other hand, the market-based interest of the organizations as such.

The basic segment

The third and last of the segments we have identified within the provider field consists of organizations that do not offer applicants any “à la carte” menu for a boarding school, any “upgrades” and select options, but only a “basic package.” Our description of the third segment will be very brief, because, first, we have consistently referred to the basic segment in the descriptions of the other two segments and, second, there are substantial intersections between the basic and choice segments, especially because the latter organizations do offer the services also offered by the basic segment organizations.

According to our survey, 14 (18 percent) of the 78 student exchange organizations operating in Germany belong to the basic segment. Fifty percent of the providers are nonprofit (a far higher proportion than in the other two segments). While the premium segment consists of only smaller providers, in the basic segment we find – similar to the choice segment – both large organizations (e.g., AFS and YFU) who place approximately 1,000 students per year (Terbeck, 2012), as well as smaller organizations with fewer than 100 students sent abroad per year.

In contrast to the premium and choice segments, the providers of the basic segment were established before the main phase of the expansion of the field in the 1990s; the average founding date is 1975. This segment includes AFS, the Rotary Jugenddienst, and YFU, three of the four providers who were the first student exchange organizations in Germany in the 1950s and who dominated the field until the 1970s; by contrast, the fourth organization, Experiment, is now a part of the choice segment.

Similar to the providers of the choice segment, the organizations of the basic segment focus on placing students in public schools abroad, where the students usually stay with host families. In contrast to the choice segment, however, the choices for students and families in the basic segment are very limited. They are almost exclusively restricted to choosing the country where the year abroad will take place. This limited scope for choice is mirrored in the price structure, since the differences in the fees paid by the families are almost exclusively determined by the choice of the country. At AFS, prices for a year abroad starting in summer range from €5,390 for various Central and Eastern European countries to over €10,390 for the United States to €15,690 for French-speaking Canada (as of June 2014; AFS, 2015). Hence, the total price range is considerably lower than that of the choice segment.

With regard to the various methods of customer acquisition, we cannot see any differences between the choice and the basic segment. In contrast to the premium segment, the organizations in these two segments use a variety of measures; they present themselves at education fairs, try to attract candidates in schools, use alumni as multipliers, and so forth. And in the design of the application and placement process, the procedures used in both segments also look very similar and contrast strongly with the premium segment. The method is, as described earlier in more detail, quite standardized and regulated for both segments, and the flexibility is correspondingly low. In addition, the basic segment lacks the aforementioned select options for families.

Even with regard to the criteria applied in the selection of students, there are only minor differences between the organizations of the basic and the choice segments. However, for the providers in the choice segment, the fact that they simultaneously offer a “standard package” and select programs for an additional price allows them to be a little more flexible and “generous” with regard to the selection criteria. This can be illustrated with the example of the United States programs from Intrax, which differentiate between a “classic,” a “flexible,” and a school select program: the “flexible” program accepts participants who are only 14 instead of 15 years of age; the grade requirements are relaxed and they can also place allergy sufferers and vegetarians (Intrax, 2015b; 2015c). The prices are staggered according to the program’s degree of flexibility: for a one-year school stay starting in the summer of the year (as of December 1, 2014), the “classic” program costs €7,590, the “flexible” program €12,190, and the school select program at least €17,790 (Intrax, 2015a).

This brings us to our last point, the question of how the providers in the basic segment have positioned themselves in the dispute over the illusio of the field – that is, what ideological goals they are pursuing with their exchange programs. Between the two poles of “promotion of intercultural exchange” and “promoting the individual development of the student,” the providers in the basic segment have taken a hybrid position – like the providers in the choice segment – and hence differ from the premium segment in this respect. But in contrast to the choice segment, the providers in the basic segment stress the idea of cultural exchange between peoples and the promotion of tolerance more, as becomes clear from the quotations from YFU and Rotary Jugenddienst introduced at the outset of this chapter. We have seen that the majority of providers in the basic segment are nonprofits and started out before the expansion phase, at a time when the idea of promoting international understanding still represented the hegemonic idea of the field. Accordingly, it is the providers in the basic segment who have struggled the most as a result of the marketization of the field since the 1990s, because the changes in the field have forced them to adopt a more market-oriented structure and ideology that partially contradicts their own self-understanding.

To conclude this chapter, let us sum up the results of our analysis of this social field, which specializes in the transmission of transnational human capital. Over the course of more than 60 years, a field of organizations specializing in placing German students at schools and boarding schools abroad has emerged in Germany, and this field has a specific structure and its own illusio. In the context of the expansion phase from the 1980s onwards, a process of diversification has also taken place within the field, meaning that we can currently distinguish between three different segments, which correspond to some extent with the different socio-structural groups that demand the services offered by each segment. In this relation, a homology is revealed between the social space and the social structural, in particular economic, positioning of the families who demand these services on the one hand and the structure of the field of providers on the other. Thus, we find a premium segment within the field, which focuses on placing students in (non-German-speaking) boarding schools. Since the costs of a one-year stay at a boarding school are considerable, the clientele of these intermediary organizations particularly consists of families with very high economic capital. In addition to this premium segment, two additional segments that specialize in traditional student exchanges have become institutionalized: a choice segment and a basic segment. These segments focus at least to some extent on a socio-structurally different clientele. The three segments also differ in their emphasis of a specific illusio – that is, what precisely the additional value of a school year abroad is.

Although many aspects of the historical development of the provider field are specific to the German context, it can be assumed that the structure identified by us should also be present in other countries. This is true mainly because the formation and expansion of the specific provider field have been driven by general developments in education that can be described using the keywords “internationalization” and “marketization,” and which should be typical not only for Germany but also for many other countries.

Related to the German case, we were able to show that the state educational institutions in Germany have responded to the increasing demand for transnational education capital by introducing language teaching in elementary schools, for example, and developing some other minor activities. But overall, efforts by state educational institutions to internationalize education have remained very limited. This has opened the door for the development and expansion of a privately organized education market in the form of bilingual daycare centers, elementary schools, and summer courses and it has also facilitated the growth of student exchange organizations. Most institutions specializing in transmitting transnational human capital are operated by private organizations and attending them is linked to paying fees, which would not apply when attending state institutions. In the process, the material capital of parents has become a significant resource for accessing the opportunity to acquire transnational human capital.