Unexpected cardiovascular collapse and death most often result from ventricular fibrillation in pts with acute or chronic atherosclerotic coronary artery disease. Other common etiologies are listed in Table 11-1. Arrhythmic causes may be provoked by electrolyte disorders (primarily hypokalemia), hypoxemia, acidosis, or massive sympathetic discharge, as may occur in CNS injury. Immediate institution of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) followed by advanced life support measures (see below) is mandatory. Ventricular fibrillation, or asystole, without institution of CPR within 4–6 min is usually fatal.

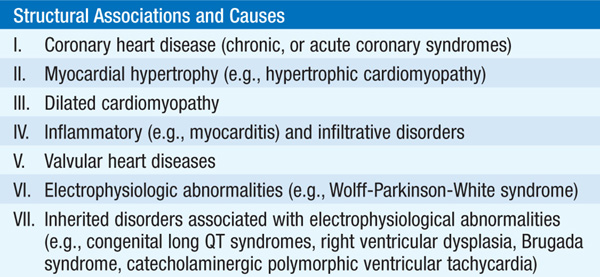

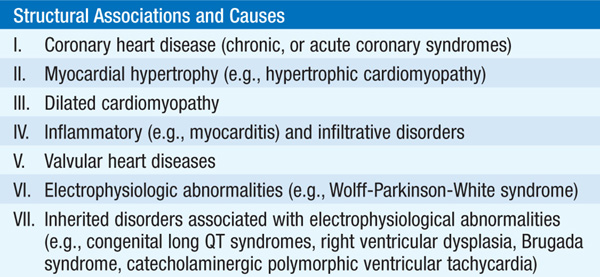

TABLE 11-1 CARDIAC ARREST AND SUDDEN CARDIAC DEATH

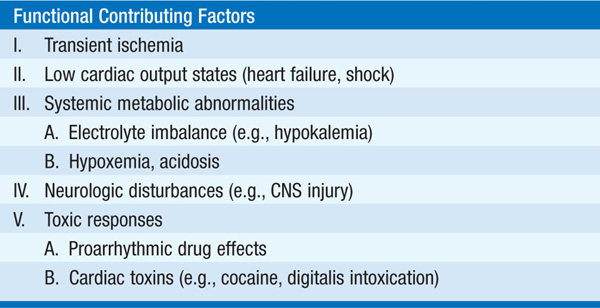

Basic life support (BLS) must commence immediately (Fig. 11-1):

FIGURE 11-1 Major steps in cardiopulmonary resuscitation. A. Begin cardiac compressions at 100 compressions/min. B. Confirm that victim has an open airway. C. Trained rescuers begin mouth-to-mouth resuscitation if advanced life support equipment is not available. (Modified from J Henderson, Emergency Medical Guide, 4th ed, New York, McGraw-Hill, 1978.)

1. Phone emergency line (e.g., 911); retrieve automated external defibrillator (AED) if quickly available.

2. If respiratory stridor is present, assess for aspiration of a foreign body and perform Heimlich maneuver.

3. Perform chest compressions (depressing sternum 4–5 cm) at rate of 100 per min without interruption. A second rescuer should attach and utilize AED if available.

4. If second trained rescuer available, tilt pt’s head backward, lift chin, and begin mouth-to-mouth respiration (pocket mask is preferable to prevent transmission of infection), while chest compressions continue. The lungs should be inflated twice in rapid succession for every 30 chest compressions. For untrained lay rescuers, chest compression only, without ventilation, is recommended until advanced life support capability arrives.

5. As soon as resuscitation equipment is available, begin advanced life support with continued chest compressions and ventilation. Although performed as simultaneously as possible, defibrillation (≥300 J monophasic, or 120–150 J biphasic) takes highest priority (Fig. 11-2), followed by placement of IV access and intubation. 100% O2 should be administered by endotracheal tube or, if rapid intubation cannot be accomplished, by bag-valve-mask device; respirations should not be interrupted for more than 30 s while attempting to intubate.

FIGURE 11-2 Management of cardiac arrest. The algorithm of ventricular fibrillation or hypotensive ventricular tachycardia begins with defibrillation attempts. If that fails, it is followed by epinephrine or vasopressin and then antiarrhythmic drugs. CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation. [Modified from Myerburg R. and Castellanos A. Chap. 23, HPIM-18.]

6. Initial IV access should be through the antecubital vein, but if drug administration is ineffective, a central line (internal jugular or subclavian) should be placed. IV NaHCO3 should be administered only if there is persistent severe acidosis (pH <7.15) despite adequate ventilation. Calcium is not routinely administered but should be given to pts with known hypocalcemia, those who have received toxic doses of calcium channel antagonists, or if acute hyperkalemia is thought to be the triggering event for resistant ventricular fibrillation.

7. The approach to cardiovascular collapse caused by bradyarrhythmias, asystole, or pulseless electrical activity is shown in Fig. 11-3.

FIGURE 11-3 The algorithms for bradyarrhythmia/asystole (left) or pulseless electrical activity (right) are dominated first by continued life support and a search for reversible causes. CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; MI, myocardial infarction. [Modified from Myerburg R. and Castellanos A. Chap. 23, HPIM-18.]

8. Therapeutic hypothermia (cooling to 32–34°C for 12–24 h) should be considered for unconscious survivors of cardiac arrest.

If cardiac arrest resulted from ventricular fibrillation in initial hours of an acute MI, follow-up is standard post-MI care (Chap. 128). For other survivors of a ventricular fibrillation arrest, further assessment, including evaluation of coronary anatomy, and left ventricular function, is typically recommended. In absence of a transient or reversible cause, placement of an implantable cardioverter defibrillator is usually indicated.

For a more detailed discussion, see Myerburg RJ, Castellanos A: Cardiovascular Collapse, Cardiac Arrest, and Sudden Cardiac Death, Chap. 273, p. 2238, in HPIM-18.