The nematodes, or roundworms, that are of medical significance can be broadly classified as either tissue or intestinal parasites.

With the exception of trichinellosis, these infections are due to invasive larval stages that do not reach maturity in humans.

Trichinellosis

Microbiology and Epidemiology Eight species of Trichinella cause human infection; two—T. spiralis and T. pseudospiralis—are found worldwide.

• Infection results when humans ingest meat (usually pork) that contains encysted Trichinella larvae.

– The larvae invade the small-bowel mucosa.

– After 1 week, female worms release new larvae that migrate to striated muscle via the circulation and encyst.

• The host immune response has little effect on muscle-dwelling larvae.

• About 12 cases of trichinellosis are reported annually in the United States.

Clinical Manifestations Most light infections (<10 larvae per gram of muscle) are asymptomatic. A burden of >50 larvae per gram can cause fatal disease.

• In the first week of infection, large numbers of parasites invading the gut usually cause diarrhea, abdominal pain, constipation, nausea, and/or vomiting.

• In the second week of infection, pts develop symptoms related to larval migration and muscle invasion: hypersensitivity reactions with fever and hypereosinophilia; periorbital and facial edema; and hemorrhages in conjunctivae, retina, and nail beds. Deaths are usually due to myocarditis with arrhythmias or heart failure.

• 2–3 weeks after infection, larval encystment in muscle causes myositis, myalgias, muscle edema, and weakness (especially in extraocular muscles; the biceps; and muscles of the jaw, neck, lower back, and diaphragm).

• Symptoms peak at 3 weeks; convalescence is prolonged.

Diagnosis Eosinophilia develops in >90% of pts, peaking at a level of >50% at 2–4 weeks after infection.

• An increase in parasite-specific antibody titers after the third week of infection confirms the diagnosis.

• Detection of larvae by microscopic examination of ≥1 g of fresh muscle tissue (i.e., not routine histopathologic sections) also confirms the diagnosis. Yields are highest near tendon insertions.

TREATMENT Trichinellosis

• Mebendazole (200–400 mg tid for 3 days; then 400 mg tid for 8–14 days) or albendazole (400 mg bid for 8–14 days) is active against enteric-stage parasites; the efficacy of these drugs against encysted larvae is inconclusive.

• Glucocorticoids (e.g., prednisone at 1 mg/kg daily for 5 days) may reduce severe myositis and myocarditis.

Prevention Cooking pork until it is no longer pink or freezing it at –15°C for 3 weeks kills larvae and prevents infection by most Trichinella species.

Visceral and Ocular Larva Migrans

Microbiology and Epidemiology Humans are an incidental host for nematodes that cause visceral larva migrans. Most cases are caused by the canine ascarid Toxocara canis. Infection results when humans—most often preschool children—ingest soil contaminated by puppy feces that contain infective T. canis eggs. Larvae penetrate the intestinal mucosa and disseminate hematogenously to a wide variety of organs (e.g., liver, lungs, CNS), provoking intense eosinophilic granulomatous responses.

Clinical Manifestations Symptomatic infections result in fever, malaise, anorexia, weight loss, cough, wheezing, rashes, hepatosplenomegaly, and profound eosinophilia (up to 90%). Ocular disease usually develops in older children or young adults and includes an eosinophilic mass that mimics retinoblastoma, endophthalmitis, uveitis, and/or chorioretinitis.

Diagnosis The clinical diagnosis can be confirmed by an ELISA for toxocaral antibodies. Stool examination for eggs is ineffective because larvae do not develop into adult worms in humans.

TREATMENT Visceral and Ocular Larva Migrans

• The vast majority of Toxocara infections are self-limited and resolve without specific therapy.

• For pts with severe disease, glucocorticoids can reduce inflammatory complications.

• Antihelminthic drugs, including mebendazole and albendazole, have not been shown to alter the course of larva migrans.

• Ocular disease can be treated with albendazole (800 mg bid) and glucocorticoids for 5–20 days.

Cutaneous Larva Migrans This disease is caused by larvae of animal hookworms, usually the dog and cat hookworm Ancylostoma braziliense. Larvae in contaminated soil penetrate human skin; intensely pruritic, erythematous lesions form along the tracks of larval migration and advance several centimeters each day. Ivermectin (a single dose of 200 μg/kg) or albendazole (200 mg bid for 3 days) can relieve the symptoms of this self-limited infestation.

Intestinal nematodes infect >1 billion persons worldwide, most commonly in regions with poor sanitation and particularly in developing countries in the tropics or subtropics. Because most helminthic parasites do not self-replicate, clinical disease (as opposed to asymptomatic infection) generally develops only with prolonged residence in an endemic area and is typically related to infection intensity.

Ascariasis

Microbiology Ascariasis is caused by Ascaris lumbricoides, the largest intestinal nematode, which reaches lengths up to 40 cm.

• Humans—primarily younger children—are infected by ingestion of fecally contaminated soil that contains ascarid eggs.

• Larvae hatch in the intestine, invade the mucosa, migrate to the lungs, break into the alveoli, ascend the bronchial tree, are swallowed, mature in the small intestine, and produce up to 240,000 eggs per day that pass in the feces.

Clinical Manifestations Most infections have a low worm burden and are asymptomatic. During lung migration of the parasite (~9–12 days after egg ingestion), pts may develop a cough and substernal discomfort, occasionally with dyspnea or blood-tinged sputum, fever, and eosinophilia.

• Eosinophilic pneumonitis (Löffler’s syndrome) may be evident.

• Heavy infections with numerous entangled worms can occasionally cause pain, small-bowel obstruction, perforation, volvulus, biliary obstruction and colic, or pancreatitis.

Laboratory Findings Ascaris eggs (65 by 45 μm) can be found in fecal samples. Adult worms can pass in the stool or through the mouth.

TREATMENT Ascariasis

A single dose of albendazole (400 mg), mebendazole (500 mg), or ivermectin (150–200 μg/kg) is effective. Pyrantel pamoate (a single dose of 11 mg/kg; maximal dose, 1 g) is safe in pregnancy.

Hookworm

Microbiology Two hookworm species, Ancylostoma duodenale and Necator americanus, cause human infections. Infectious larvae present in soil penetrate the skin, reach the lungs via the bloodstream, invade the alveoli, ascend the airways, are swallowed, reach the small intestine, mature into adult worms, attach to the mucosa, and suck blood (0.2 mL/d per Ancylostoma adult) and interstitial fluid.

Clinical Manifestations Most infections are asymptomatic. Chronic infection causes iron deficiency and—in marginally nourished persons—progressive anemia and hypoproteinemia, weakness, and shortness of breath. Larvae may cause pruritic rash (“ground itch”) at the site of skin penetration as well as serpiginous tracks of subcutaneous migration (similar to those of cutaneous larva migrans).

Laboratory Findings Hookworm eggs (40 by 60 μm) can be found in the feces. Stool concentration may be needed for the diagnosis of light infections.

TREATMENT Hookworm

• Albendazole (400 mg once), mebendazole (500 mg once), or pyrantel pamoate (11 mg/kg daily for 3 days) is effective. Nutritional support, iron replacement, and deworming are undertaken as needed.

Strongyloidiasis

Microbiology and Epidemiology Unlike other helminths, Strongyloides stercoralis can replicate in the human host, permitting ongoing cycles of autoinfection from endogenously produced larvae.

• Infection results when filariform larvae in fecally contaminated soil penetrate the skin or mucous membranes.

– Larvae travel through the bloodstream to the lungs, break through into alveolar spaces, ascend the bronchial tree, are swallowed, reach the small intestine, mature into adult worms, and penetrate the mucosa of the proximal small bowel; eggs hatch in the intestinal mucosa.

– Rhabditiform larvae can pass with the feces into the soil or can develop into filariform larvae that penetrate the colonic wall or peri-anal skin and enter the circulation to establish ongoing autoinfection.

• Autoinfection is constrained by unknown factors of the host immune system, disruption of which (e.g., by glucocorticoid therapy) can lead to hyperinfection.

Clinical Features Uncomplicated disease is associated with mild cutaneous and/or abdominal manifestations such as recurrent urticaria, larva currens (a pathognomonic serpiginous, pruritic, erythematous eruption along the course of larval migration that may advance up to 10 cm/h), abdominal pain, nausea, diarrhea, bleeding, and weight loss.

• Disseminated disease involves tissues outside the GI tract and lungs, including the CNS, peritoneum, liver, and kidney.

– Gram-negative sepsis, pneumonia, or meningitis can complicate or dominate the clinical course.

– Disease can be fatal in pts given glucocorticoids; disseminated infection is uncommon among pts with HIV-1 infection.

• Fluctuating eosinophilia is common in uncomplicated disease but is uncommon in disseminated disease.

Diagnosis A single stool examination detects rhabditiform larvae (~250 μm long) in about one-third of uncomplicated infections. Duodenojejunal contents can be sampled if stool examinations are repeatedly negative.

• Antibodies can be detected by ELISA.

• In disseminated infection, filariform larvae can be found in stool or at sites of larval migration (e.g., sputum, bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, surgical drainage fluid).

TREATMENT Strongyloidiasis

• Ivermectin (200 μg/kg daily for 2 days) is more effective than albendazole (400 mg daily for 3 days). Asymptomatic pts should be treated, given the potential for later fatal hyperinfection.

• Disseminated disease should be treated with ivermectin for ≥5–7 days (or until the parasites are eradicated).

Enterobiasis

Microbiology and Epidemiology Enterobiasis (pinworm) is caused by Enterobius vermicularis and affects ~40 million people in the U.S. (primarily children).

• Gravid female worms migrate nocturnally from the cecum to the peri-anal region, each releasing up to 10,000 immature eggs that become infective within hours.

• Autoinfection and person-to-person transmission result from perianal scratching and transport of infective eggs to the mouth.

Clinical Manifestations Perianal pruritus is the cardinal symptom and is often worst at night. Eosinophilia is uncommon.

Diagnosis Eggs (55 by 25 μm and flattened on one side) are detected by microscopic examination of cellulose acetate tape applied to the perianal region in the morning.

TREATMENT Enterobiasis

• One dose of mebendazole (100 mg), albendazole (400 mg), or pyrantel pamoate (11 mg/kg; maximum, 1 g) is given, with the same treatment repeated after 2 weeks. Household members should also be treated to avoid reservoirs of potential reinfection.

Filarial worms, which infect more than 170 million people worldwide, are nematodes that dwell in the SC tissue and lymphatics. Usually, infection is established only with repeated and prolonged exposures to infective larvae; however, filarial disease is characteristically more intense and acute in newly exposed individuals than in natives of endemic areas.

• Filarial parasites have a complex life cycle, including infective larval stages carried by insects and adult worms that reside in humans.

– The offspring of adults are microfilariae (200–250 μm long, 5–7 μm wide) that either circulate in the blood or migrate through the skin.

– Microfilariae are ingested by the arthropod vector and develop over 1–2 weeks into new infective larvae.

• A Rickettsia-like endosymbiont, Wolbachia, is found in all stages of Brugia, Wuchereria, Mansonella, and Onchocerca and has become a target for antifilarial chemotherapy.

Lymphatic Filariasis

Microbiology Lymphatic filariasis is caused by Wuchereria bancrofti (most commonly), Brugia malayi, or B. timori, which can reside in and cause inflammatory damage to lymphatic channels or lymph nodes.

Clinical Manifestations Subclinical microfilaremia, hydrocele, acute adenolymphangitis (ADL), and chronic lymphatic disease are the main clinical presentations.

• ADL is associated with high fever, lymphatic inflammation, and transient local edema. Both the upper and lower extremities can be involved in both bancroftian and brugian filariasis, but W. bancrofti almost exclusively affects genital lymphatics.

• ADL may progress to more chronic lymphatic obstruction and elephantiasis with brawny edema, thickening of the SC tissues, and hyperkeratosis. Superinfection is a problem.

Diagnosis Detection of the parasite is difficult, but microfilariae can be found in peripheral blood, hydrocele fluid, and occasionally other body fluids.

• Timing of blood collection is critical and should be based on the periodicity of the microfilariae in the endemic region involved (primarily nocturnal in many regions).

• Two assays are available to detect W. bancrofti circulating antigens, and a PCR has been developed to detect DNA of both W. bancrofti and B. malayi in the blood.

• High-frequency ultrasound (with Doppler techniques) of the scrotum or the female breast can identify motile adult worms.

• The presence of antifilarial antibody supports the diagnosis, but cross-reactivity with other helminthic infections makes interpretation of this finding difficult.

TREATMENT Lymphatic Filariasis

• Pts with active lymphatic filariasis (defined by microfilaremia, antigen positivity, or adult worms on ultrasound) should be treated with diethylcarbamazine (DEC; 6 mg/kg daily for 12 days). Albendazole (400 mg bid for 21 days), albendazole and DEC both given daily for 7 days, and doxycycline (100 mg bid for 4–6 weeks) are alternative regimens with macrofilaricidal efficacy.

• A single dose of albendazole (400 mg) combined with DEC (6 mg/kg) or ivermectin (200 μg/kg) has sustained microfilaricidal activity and is used in lymphatic filariasis eradication campaigns.

• For pts with chronic lymphatic filariasis, treatment regimens should focus on hygiene, prevention of secondary bacterial infections, and physiotherapy. Drug treatment should be reserved for individuals with evidence of active infection.

Onchocerciasis

Microbiology and Epidemiology Onchocerciasis (“river blindness”) is caused by Onchocerca volvulus, which infects 37 million people worldwide and is transmitted by the bite of an infected blackfly near free-flowing rivers and streams.

• Larvae deposited by the blackfly develop into adult worms (females and males are ~40–60 cm and ~3–6 cm in length, respectively) that are found in SC nodules (onchocercomata). About 7 months to 3 years after infection, the gravid female releases microfilariae that migrate out of the nodules and concentrate in the dermis.

• In contrast to lymphatic filariasis, onchocerciasis is characterized by microfilarial induction of inflammation.

Clinical Manifestations Onchocerciasis most commonly presents as dermatologic manifestations (an intensely pruritic papular rash or firm nontender onchocercomata), but visual impairment is the most serious complication in pts with moderate or heavy infections.

• Conjunctivitis with photophobia is an early ocular finding.

• Sclerosing keratitis (the leading cause of onchocercal blindness in Africa, affecting 1–5% of pts), anterior uveitis, iridocyclitis, and secondary glaucoma due to pupillary deformities are more serious ocular complications.

Diagnosis A definitive diagnosis is based on the finding of an adult worm in an excised nodule or of microfilariae in a skin snip.

• Specific antibody assays and PCR to detect onchocercal DNA are available in reference laboratories.

• Eosinophilia and elevated serum IgE levels are common but nonspecific.

TREATMENT Onchocerciasis

• Ivermectin (a single dose of 150 μg/kg), given yearly or semiannually, is microfilaricidal and is the mainstay of treatment.

– In African regions where O. volvulus is co-endemic with Loa loa, ivermectin is contraindicated because of the risk of severe post-treatment encephalopathy.

– Doxycycline therapy for 6 weeks is macrofilaristatic, rendering adult female worms sterile for long periods, and also targets the Wolbachia endosymbiont.

• Nodules on the head should be excised to avoid ocular infection.

• The trematodes, or flatworms, may be classified according to the tissues invaded by the adult flukes: blood, biliary tree, intestines, and lungs.

• The life cycle involves a definitive mammalian host (e.g., humans), in which adult worms produce eggs through sexual reproduction, and an intermediate host (e.g., snails), in which miracidial forms undergo asexual reproduction to form cercariae. Worms do not multiply within the definitive host.

• Human infection results from either direct penetration of intact skin or ingestion.

• Infections with trematodes that migrate through or reside in host tissues are associated with a moderate to high degree of peripheral-blood eosinophilia.

Schistosomiasis

Microbiology and Epidemiology Five species cause human schistosomiasis: the intestinal species Schistosoma mansoni, S. japonicum, S. mekongi, and S. intercalatum and the urinary species S. haematobium.

• After infective cercariae penetrate intact skin, they mature into schistosomula and migrate through venous or lymphatic vessels to the lungs and ultimately the liver parenchyma. Sexually mature worms migrate to the veins of the bladder and ureters (S. haematobium) or the mesentery (S. mansoni, S. japonicum, S. mekongi, S. intercalatum) and deposit eggs.

– Some mature ova are extruded into the intestinal or urinary lumina, from which they may be voided and ultimately may reach water and perpetuate the life cycle.

– The persistence of ova in tissues leads to a granulomatous host response and fibrosis.

• These blood flukes infect 200–300 million persons in South America, the Caribbean, Africa, the Middle East, and Southeast Asia.

Clinical Manifestations Schistosomiasis occurs in three stages that vary by species, intensity of infection, and host factors.

• Cercarial invasion, most often with S. mansoni and S. japonicum infections, causes a pruritic maculopapular rash (“swimmers’ itch”) 2–3 days later.

• Acute schistosomiasis (Katayama fever) presents 4–8 weeks after skin invasion as a serum sickness–like illness characterized by fever, generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, and significant eosinophilia.

• Chronic schistosomiasis causes manifestations that depend primarily on the schistosome species.

– Intestinal species cause colicky abdominal pain, bloody diarrhea, anemia, hepatosplenomegaly, portal hypertension, and esophageal varices with bleeding.

– Urinary species cause dysuria, frequency, hematuria, obstruction with hydroureter and hydronephrosis, fibrosis of bladder granulomas, and late development of squamous cell carcinoma of the bladder.

– Pulmonary disease (e.g., endarteritis obliterans, pulmonary hypertension, cor pulmonale) and CNS disease (e.g., Jacksonian epilepsy, transverse myelitis) can occur and are due to granulomas and fibrosis.

Diagnosis Diagnosis is based on geographic history, clinical presentation, and presence of schistosome ova in excreta.

• Serologic assays for schistosomal antibodies (available through the CDC in the U.S.) may yield positive results before eggs are seen in excreta.

• Infection may also be diagnosed by examination of tissue samples, typically from rectal biopsies.

TREATMENT Schistosomiasis

• Because antischistosomal therapy has no significant impact on maturing worms, supportive measures and the consideration of glucocorticoid treatment constitute initial management for acute schistosomiasis.

– After the acute critical phase has resolved, a single day of treatment with praziquantel (20 mg/kg bid for S. mansoni, S. intercalatum, and S. haematobium infections; 20 mg/kg tid for S. japonicum and S. mekongi infections) results in parasitologic cure in ~85% of cases and reduces egg counts by >90%.

– Late established manifestations, such as fibrosis, do not improve with treatment.

Prevention Travelers to endemic regions should avoid contact with all freshwater bodies.

Liver (Biliary) Flukes

• Clonorchiasis (due to Clonorchis sinensis) and opisthorchiasis (due to Opisthorchis viverrini and O. felineus) occur in Southeast Asia and Eastern Europe.

– Infection is acquired by ingestion of contaminated raw freshwater fish; larvae travel through the ampulla of Vater and mature in biliary canaliculi.

– Most infected individuals are asymptomatic; chronic or repeated infection causes cholangitis, cholangiohepatitis, and biliary obstruction and is associated with cholangiocarcinoma.

– Therapy for acute infection consists of praziquantel administration (25 mg/kg tid for 1 day).

• Fascioliasis (due to Fasciola hepatica and F. gigantica) is endemic in sheep-raising countries and has a worldwide prevalence of 17 million cases.

– Infection is acquired by ingestion of contaminated aquatic plants (e.g., watercress).

– Acute disease develops 1–2 weeks after infection and causes fever, right-upper-quadrant pain, hepatomegaly, and eosinophilia. Chronic infection is infrequently associated with bile duct obstruction and biliary cirrhosis.

– For treatment, triclabendazole is given as a single dose of 10 mg/kg.

• Stool ova and parasite (O & P) examination diagnoses infection with liver flukes.

Lung Flukes Infection with Paragonimus spp. is acquired by ingestion of contaminated crayfish and freshwater crabs.

• Acute infection causes lung hemorrhage, necrosis with cyst formation, and parenchymal eosinophilic infiltrates. A productive cough with brownish or bloody sputum, in association with peripheral-blood eosinophilia, is the usual presentation in pts with heavy infection.

– In chronic cases, bronchitis or bronchiectasis may predominate.

– CNS disease can also occur and can result in seizures.

• The diagnosis is made by O & P examination of sputum or stool; serology can be helpful.

• Praziquantel (25 mg/kg tid for 2 days) is the recommended therapy.

The cestodes, or tapeworms, are segmented worms that can be classified into two groups according to whether humans are the definitive or the intermediate hosts. The tapeworm attaches to intestinal mucosa via sucking cups or hooks located on the scolex. Proglottids (segments) form behind the scolex and constitute the bulk of the tapeworm.

Taeniasis Saginata and Taeniasis Asiatica

Microbiology Humans are the definitive host for Taenia saginata, the beef tapeworm, and T. asiatica, the swine tapeworm, which inhabit the upper jejunum. Eggs are excreted in feces and ingested by cattle or other herbivores (T. saginata) or pigs (T. asiatica); larvae encyst (cysticerci) in the striated muscles of these animals. When humans ingest raw or undercooked meat, the cysticerci mature into adult worms in ~2 months.

Clinical Manifestations Pts become aware of the infection by noting passage of motile proglottids in their feces. They may experience perianal discomfort, mild abdominal pain, nausea, change in appetite, weakness, and weight loss.

Diagnosis The diagnosis is made by detection of eggs or proglottids in the stool; eggs may be detected in the perianal area by the cellophane-tape test (as in pinworm infection). Eosinophilia and elevated IgE levels may occur.

Praziquantel is given in a single dose of 10 mg/kg.

Taeniasis Solium and Cysticercosis

Microbiology and Pathogenesis Humans are the definitive host and pigs the usual intermediate host for T. solium, the pork tapeworm.

• The disease has two forms, which depend on the form of parasite ingested.

– By ingesting undercooked pork containing cysticerci, humans develop intestinal tapeworms and a disease similar to taeniasis saginata.

– If humans ingest T. solium eggs (e.g., as a result of close contact with a tapeworm carrier or via autoinfection), they develop cysticercosis due to larvae penetrating the intestinal wall and migrating to many tissues.

Clinical Manifestations Intestinal infections are generally asymptomatic except for fecal passage of proglottids. The presentation of cysticercosis depends on the number and location of cysticerci as well as the extent of associated inflammatory responses or scarring.

• Cysticerci can be found anywhere in the body but most often are detected in the brain, skeletal muscle, SC tissue, or eye.

• Neurologic manifestations are most common and include seizures (due to inflammation surrounding cysticerci in the brain), hydrocephalus (from obstruction of CSF flow by cysticerci and accompanying inflammation or by arachnoiditis), and signs of increased intracranial pressure (e.g., headache, nausea, vomiting, changes in vision).

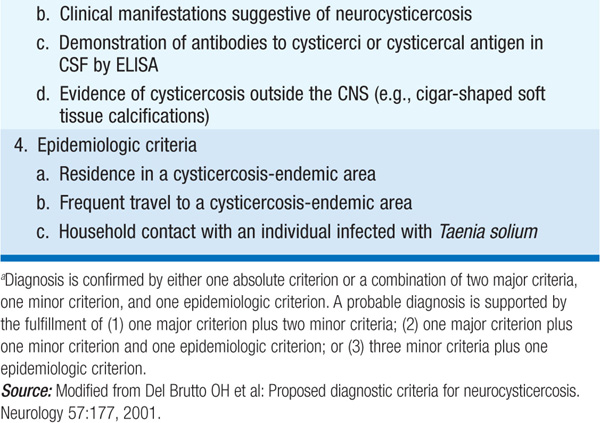

Diagnosis Intestinal infection is diagnosed by detection of eggs or proglottids in stool. A consensus conference has delineated criteria for the diagnosis of cysticercosis (Table 118-1). Findings on neuroimaging include cystic lesions with or without enhancement, one or more nodular calcifications, or focal enhancing lesions.

TABLE 118-1 DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR HUMAN CYSTICERCOSISa

TREATMENT Taeniasis Solium and Cysticercosis

• Intestinal infections respond to a single dose of praziquantel (10 mg/kg), but this treatment may evoke an inflammatory response in the CNS if there is cryptic cysticercosis.

• Neurocysticercosis can be treated with albendazole (15 mg/kg per day for 8–28 days) or praziquantel (50–100 mg/kg daily in 3 divided doses for 15–30 days).

– Given the potential for an inflammatory response to treatment, pts should be carefully monitored and high-dose glucocorticoids should be used during treatment.

– Since glucocorticoids induce praziquantel metabolism, cimetidine should be given with praziquantel to inhibit this effect.

– Supportive measures include antiepileptic administration and treatment of hydrocephalus as indicated.

Microbiology and Epidemiology Humans are an intermediate host for Echinococcus larvae and acquire echinococcal disease by ingesting eggs spread by canine feces (for E. granulosus).

• After ingestion, embryos escape from the eggs, penetrate the intestinal mucosa, enter the portal circulation, and are carried to many organs but particularly the liver and lungs. Larvae develop into fluid-filled unilocular hydatid cysts within which daughter cysts develop, as do germinating cystic structures (brood capsules). Cysts expand over years.

• Disease is prevalent on all continents, particularly in areas where livestock is raised in association with dogs.

• E. multilocularis, found in arctic or subarctic regions, is similar, but wild canines (e.g., foxes) are the definitive hosts and rodents are the intermediate hosts. The parasite is multilocular, and vesicles progressively invade host tissue.

Clinical Manifestations Expanding cysts exert the effects of space-occupying lesions, causing symptoms in the affected organ (usually liver and lung); the liver is involved in two-thirds of E. granulosus infections and ~100% of E. multilocularis infections.

• Pts with hepatic disease most commonly present with abdominal pain or a palpable mass in the right upper quadrant. Compression of a bile duct may mimic biliary disease, and rupture or leakage from a hydatid cyst may cause fever, pruritus, urticaria, eosinophilia, or anaphylaxis.

• Pulmonary cysts may rupture into the bronchial tree or the peritoneal cavity and cause cough, salty phlegm, chest pain, or hemoptysis.

• Rupture of cysts may result in multifocal dissemination.

• E. multilocularis disease may present as a hepatic tumor, with destruction of the liver and extension into adjoining (e.g., lungs, kidneys) or distant (e.g., brain, spleen) organs.

Diagnosis Radiographic imaging is important in detecting and evaluating echinococcal cysts.

• Daughter cysts within a larger cyst are pathognomonic of E. granulosus. Eggshell or mural calcification on CT is also indicative of E. granulosus infections.

• Serologic testing yields positive results in ~90% of pts with hepatic disease, but results can be negative in up to half of pts with lung cysts.

• Aspiration of cysts usually is not attempted because leakage of cyst fluid can cause dissemination or anaphylactic reactions.

TREATMENT Echinococcosis

• Therapy is based on considerations of the size, location, and manifestations of cysts and the overall health of the pt. Ultrasound staging is recommended for E. granulosus infection.

• For some uncomplicated lesions, PAIR [percutaneous aspiration, infusion of scolicidal agents (95% ethanol or hypertonic saline), and reaspiration] is recommended.

– Albendazole (7.5 mg/kg bid for 4 days before the procedure and for at least 4 weeks afterward) is given for prophylaxis of secondary peritoneal echinococcosis due to inadvertent spillage of fluid during this treatment.

– PAIR is contraindicated for superficial cysts, for cysts with multiple thick internal septal divisions, and for cysts communicating with the biliary tree.

• Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for complicated E. granulosus cysts.

– Albendazole should also be given prophylactically, as just described. Praziquantel (50 mg/kg daily for 2 weeks) may hasten the death of protoscolices.

– Medical therapy alone with albendazole for 12 weeks to 6 months results in cure in ~30% of cases and in clinical improvement in another 50%.

• E. multilocularis infection is treated surgically, and albendazole is given for at least 2 years after presumptively curative surgery. If surgery is not curative, albendazole should be continued indefinitely.

Diphyllobothriasis Diphyllobothrium latum, the longest tapeworm (up to 25 m), attaches to the ileal and occasionally the jejunal mucosa. Humans are infected by consumption of infected raw or smoked fish. Symptoms are rare and usually mild, but infection, particularly in Scandinavia, can cause vitamin B12 deficiency because the tapeworm absorbs large amounts of vitamin B12 and interferes with ileal B12 absorption. Up to 2% of infected pts, especially the elderly, have megaloblastic anemia resembling pernicious anemia and can suffer neurologic sequelae due to B12 deficiency. The diagnosis is made by detection of eggs in the stool. Praziquantel (5–10 mg/kg once) is highly effective.

Ectoparasites are arthropods or helminths that infest the skin of other animals, from which they derive sustenance and shelter. These organisms can inflict direct injury, elicit hypersensitivity, or inoculate toxins or pathogens.

Scabies

Etiology and Epidemiology Scabies is caused by the human itch mite Sarcoptes scabiei and infests ~300 million people worldwide.

• Gravid female mites burrow beneath the stratum corneum, deposit eggs that mature in 2 weeks, and emerge as adults to reinvade the same or another host.

• Scabies transmission is facilitated by intimate contact with an infested person and by crowding, uncleanliness, or contact with multiple sexual partners.

Clinical Manifestations Itching, which is due to a sensitization reaction against excreta of the mite, is worst at night and after a hot shower. Burrows appear as dark wavy lines (≤15 mm in length), with most lesions located between the fingers or on the volar wrists, elbows, and penis. Norwegian or crusted scabies—hyperinfestation with thousands of mites—is associated with glucocorticoid use and immunodeficiency diseases.

Diagnosis Scrapings from unroofed burrows reveal the mite, its eggs, or fecal pellets.

TREATMENT Scabies

• Permethrin cream (5%) should be applied thinly behind the ears and from the neck down after bathing and removed 8 h later with soap and water. A dose of ivermectin (200 μg/kg) is also effective but has not yet been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for scabies treatment.

• For crusted scabies, first a keratolytic agent (e.g., 6% salicylic acid) and then scabicides are applied to the scalp, face, and ears in addition to the rest of the body. Two doses of ivermectin, separated by an interval of 1–2 weeks, may be required for pts with crusted scabies.

• Itching and hypersensitivity may persist for weeks or months in scabies and should be managed with symptom-based treatment. Bedding and clothing should be washed in hot water and dried in a heated dryer, and close contacts (regardless of symptoms) should be treated to prevent reinfestations.

Pediculiasis

Etiology and Epidemiology Nymphs and adults of human lice—Pediculus capitis (the head louse), P. humanus (the body louse), and Pthirus pubis (the pubic louse)—feed at least once a day and ingest human blood exclusively. The saliva of these lice produces an irritating rash in sensitized persons. Eggs are cemented firmly to hair or clothing, and empty eggs (nits) remain affixed for months after hatching. Lice are generally transmitted from person to person. Head lice are transmitted among schoolchildren and body lice among disaster victims and indigent people; pubic lice are usually transmitted sexually. The body louse is a vector for the transmission of diseases such as louse-borne typhus, relapsing fever, and trench fever.

Diagnosis The diagnosis can be suspected if nits are detected, but confirmatory measures should include the demonstration of a live louse.

TREATMENT Pediculiasis

• If live lice are found, treatment with 1% permethrin (two 10-min applications 10 days apart) is usually adequate. If this course fails, treatment for ≤12 h with 0.5% malathion may be indicated. Eyelid infestations should be treated with petrolatum applied for 3–4 days.

• Body lice usually are eliminated by bathing and by changing to laundered clothes.

– Pediculicides applied from head to foot may be needed in hirsute pts to remove body lice.

– Clothes and bedding should be deloused by placement in a hot dryer for 30 minutes or by heat pressing.

Myiasis In this infestation, maggots invade living or necrotic tissue or body cavities and produce clinical syndromes that vary with the species of fly. Certain flies are attracted to blood and pus, and newly hatched larvae enter wounds or diseased skin. Treatment consists of maggot removal and tissue debridement.

Leech Infestations Medicinal leeches can reduce venous congestion in surgical flaps or replanted body parts. Pts occasionally develop sepsis from Aeromonas hydrophila, which colonizes the gullets of commercially available leeches.

For a more detailed discussion, see Reed SL, Davis CE: Laboratory Diagnosis of Parasitic Infections, Chap. e25; Moore TA: Pharmacology of Agents Used to Treat Parasitic Infections, Chap. e26; and Moore TA: Agents Used to Treat Parasitic Infections, Chap. 208, p. 1675; Weller PF: Trichinellosis and Other Tissue Nematode Infections, Chap. 216, p. 1735; Weller PF, Nutman TB: Intestinal Nematode Infections, Chap. 217, p. 1739; Nutman TB, Weller PF: Filarial and Related Infections, Chap. 218, p. 1745; Mahmoud AAF: Schistosomiasis and Other Trematode Infections, Chap. 219, p. 1752; White AC Jr, Weller PF: Cestode Infections, Chap. 220, p. 1759; and Pollack RJ: Ectoparasite Infestations and Arthropod Bites and Stings, Chap. 397, p. 3576, in HPIM-18.