Portal hypertension is defined as elevation of the hepatic venous pressure gradient to >5 mmHg, which occurs as a consequence of cirrhosis (Chap. 165). It is caused by increased intrahepatic resistance to the passage of blood flow through the liver due to cirrhosis together with increased splanchnic blood flow due to vasodilatation within the splanchnic vascular bed.

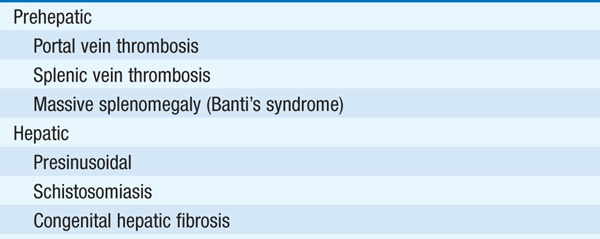

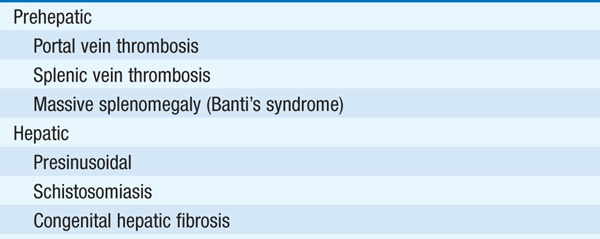

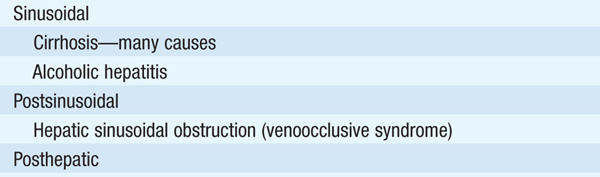

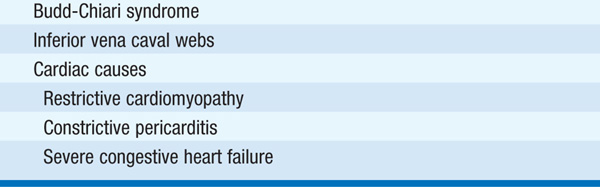

TABLE 166-1 CLASSIFICATION OF PORTAL HYPERTENSION

The primary complications of portal hypertension are gastroesophageal varices with hemorrhage, ascites (Chap. 49), hypersplenism, hepatic encephalopathy, spontaneous bacterial peritonitis (Chap. 49), hepatorenal syndrome (Chap. 49), hepatocellular carcinoma (Chap. 78).

About one-third of pts with cirrhosis have varices, and one-third of pts with varices will develop bleeding. Bleeding is a life-threatening complication; risk of bleeding correlates with variceal size and location, the degree of portal hypertension (portal venous pressure >12 mmHg), and the severity of cirrhosis, e.g., Child-Pugh classification (see Table 165-3).

Esophagogastroscopy: procedure of choice for evaluation of upper GI hemorrhage in pts with known or suspected portal hypertension. Celiac and mesenteric arteriography are alternatives when massive bleeding prevents endoscopy and to evaluate portal vein patency (portal vein may also be studied by ultrasound with Doppler and MRI).

TREATMENT Esophagogastric Varices

See Chap. 47 for general measures to treat GI bleeding.

CONTROL OF ACUTE BLEEDING

Choice of approach depends on clinical setting and availability.

1. Endoscopic intervention is employed as first-line treatment to control bleeding acutely. Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) is used to control acute bleeding in >90% of cases. EVL is less successful when varices extend into proximal stomach. Some endoscopists will use variceal injection (sclerotherapy) as initial therapy, particularly when bleeding is vigorous.

2. Vasoconstricting agents: somatostatin or octreotide (50–100 μg/h by continuous infusion).

3. Balloon tamponade (Blakemore-Sengstaken or Minnesota tube). Can be used when endoscopic therapy is not immediately available or in pts who need stabilization prior to endoscopic therapy. Complications—obstruction of pharynx, asphyxiation, aspiration, esophageal ulceration. Generally reserved for massive bleeding, failure of vasopressin and/or endoscopic therapy.

4. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS)—portacaval shunt placed by interventional radiologic technique, reserved for failure of other approaches; risk of hepatic encephalopathy (20–30%), shunt stenosis or occlusion (30–60%), infection.

PREVENTION OF RECURRENT BLEEDING

1. EVL should be repeated until obliteration of all varices is accomplished.

2. Propranolol or nadolol—nonselective beta blockers that act as portal venous antihypertensives; may decrease the risk of variceal hemorrhage and mortality due to hemorrhage.

3. TIPS—regarded as useful “bridge” to liver transplantation in pt who has failed pharmacologic therapy and is awaiting a donor liver.

4. Portosystemic shunt surgery used less commonly with the advent of TIPS; could be considered for pts with good hepatic synthetic function.

PREVENTION OF INITIAL BLEED

For pts at high risk of variceal bleeding, consider prophylaxis with EVL and/or nonselective beta blockers.

An alteration in mental status and cognitive function occurring in the presence of liver failure; may be acute and reversible or chronic and progressive.

Confusion, slurred speech, change in personality that can include being violent and hard to manage, being sleepy and difficult to arouse, asterixis (flapping tremor). Can progress to coma; initially responsive to noxious stimuli, later unresponsive.

Gut-derived neurotoxins that are not removed by the liver because of vascular shunting and decreased hepatic mass reach the brain and cause the symptoms of hepatic encephalopathy. Ammonia levels are typically elevated in encephalopathy, but the correlation between the severity of liver disease and height of ammonia levels is often poor. Other compounds that may contribute include false neurotransmitters and mercaptans.

GI bleeding, azotemia, constipation, high-protein meal, hypokalemic alkalosis, CNS depressant drugs (e.g., benzodiazepines and barbiturates), hypoxia, hypercarbia, sepsis.

TREATMENT Hepatic Encephalopathy

Remove precipitants; correct electrolyte imbalances. Lactulose (nonabsorbable disaccharide) results in colonic acidification and diarrhea and is the mainstay of treatment; goal is to produce 2–3 soft stools per day. Poorly absorbed antibiotics are often used in pts who do not tolerate lactulose, with alternating administration of neomycin and metronidazole being used to reduce the individual side effects of each. Rifaximin has recently also been used; zinc supplementation is sometimes helpful. Liver transplantation when otherwise indicated.