![]()

BACKSTORY

Pre-1914 History

The creation of the French navy dates back to Cardinal Richelieu, minister of King Louis XIII (1624–42), and its organization to Jean-Baptiste Colbert, minister of Louis XIV (1665–83). From its foundation the French navy alternated between periods of relative splendor when supported by the royal powers and lean periods when the same powers neglected it. In general, however, the crown gave priority to the protection of the northern and eastern borders, the traditional invasion routes into France, not to the navy.

The French navy distinguished itself in the American War of Independence (1778–83), especially in the battle of the Virginia Capes, but was weakened by the revolution that began in 1789, and it was then misused by Napoleon I (1804–15). The defeat at Trafalgar on 21 October 1805 condemned the navy to secondary roles, such as warfare against commerce. The navy, partially restored during the reconstruction period (1815–30), was able to land 35,000 men near Algiers on 14 June 1830, in the prelude to the conquest of Algeria. From that time, the French considered the link between the French mainland and North Africa to be vital.

The imperial navy of Napoleon III (1852–70) was the world’s second largest. Its ships were often technologically advanced, in some case even envied by the British. The French and British navies operated together during the 1853–56 Crimean War. The war with Prussia began in August 1870; France was defeated in the land campaign too swiftly for the navy’s blockade of the German coast to be effective. The navy’s contributions, such as the pinning down of 100,000 German soldiers to oppose a potential landing and the uninterrupted movement of supplies by sea, remain largely ignored. French sailors stood out, however, during the siege of Paris (18 September 1870–26 January 1871).

The Third Republic replaced the Second Empire. The German annexation of Alsace and part of Lorraine under the Treaty of Frankfurt on 10 May 1871 traumatized France. The nation focused on the “blue Vosges,” which marked the new frontier with the German Empire created at Versailles on 18 January 1871, and assigned priority to the army’s reconstitution.

In the late nineteenth century, France wanted a war of revenge with Germany and approached Russia with a proposal that it take the Germans from behind. Overseas expansion, blocked several times by the British, was reprised in 1830 but without any real popular support at home, and it was often frustrated by British superiority. The major European powers divided Africa at Berlin in June 1878. This did not prevent crises, however. The Fashoda situation with Great Britain between July and November 1898 had to be resolved by diplomacy because the French were aware that their navy could not oppose the British. The Franco-German Moroccan crises of 1905 and 1911 also ended with diplomatic compromises. Despite these setbacks, France controlled by 1914 a vast colonial empire that included northern and western Africa and Indochina and was the second largest in the world, after only Britain.

By this time, both the French and British—beginning to feel threatened by the development of Germany, including that of its fleet—reconciled and established the Entente Cordiale on 8 April 1904. In 1914, Europe was divided into two blocs: the Triple Entente (France, England, and Russia) and the Triple Alliance (Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy, which joined in 1915).

Mission/Function

The French navy’s primary mission had long been to oppose Britain’s Royal Navy and to prevent any foreign incursions against or “insults” to the French coast (hence the proliferation of torpedo-boat squadrons to cover ports). Coastal defense was the navy’s top priority in the 1872 program, which set the fleet’s force level and emphasized overseas deployment. As the German navy remained negligible, the main enemy for the French navy was still Great Britain, but there was also a need to account for the Italian threat.

The navy’s expansion was required to oppose the British and ensure links with the empire. Normally, the budget voted on annually by the parliamentary assembly provided for the construction of warships according to the navy’s demands. But political instability (forty-four navy ministers served between 1871 and August 1914) did not facilitate a coherent policy. Also, technology was changing rapidly between 1870 and 1914, and construction times were excessive due to a disorganized industry. This led to warships that were virtually obsolete by the time they were commissioned.

A new philosophy, that of the Jeune École, or Young School, which disrupted the nation’s entire shipbuilding policy, appeared in 1882. Arising from the ideas of Admiral Hyacinthe L. T. Aube (1826–90), this philosophy advocated the construction of many small vessels armed with torpedoes and the near abandonment of large warships, such as battleships, which could be easily sunk by one torpedo. No battleships were ordered between 1882 and 1889. By contrast, 370 torpedo boats were built between 1875 and 1908, including nearly three hundred from 1885. They were distributed among the numerous ports of France and North Africa, ready to repel a British attack and give each port a “mobile defense.” The desire to tackle British trade during a guerre de course led to the construction of raiding cruisers, many with limited military characteristics, that could operate independently.

In 1890 a new naval statute established a battle-line fleet (twenty-four battleships), a coastal-defense fleet (seventeen coastal battleships, 220 torpedo boats), and an overseas fleet (thirty-four cruisers). Ten battleships were built between 1890 and 1907, forming “the specimen fleet,” only three of them identical enough to constitute a homogeneous formation. The navy also constructed coastal-defense battleships, which lacked true nautical qualities, and outmoded armored cruisers. In 1900, however, the submersible torpedo boat Narval, designed by the engineer Maxime Laubeuf, was commissioned. Narval incorporated many advances, including a periscope and improved surface steam propulsion, and helped pave the way to operational submarines with increased endurance (generally two days).

The 1900 program called for a 1908 fleet of twenty-eight battleships, twenty-four armored cruisers, fifty-two destroyers, 263 torpedo boats, and thirty-eight submarines. The Entente Cordiale eliminated the principal risk of naval war with France’s cross-Channel neighbor, but the development of the Italian and Austrian navies increased the danger in the Mediterranean. During 1905, flaws in the Jeune École theory were demonstrated by the battle of Tsushima. The 1900 statute was revised in 1906 to provide for thirty-four battleships, thirty-six armored cruisers, six scout cruisers, 109 destroyers, 131 submarines, and 179 torpedo boats. The emergence of Dreadnought did not immediately disrupt the building program, since the French laid down in 1907 and 1908 the six 18,000-ton battleships of the Danton class. By this time the French, with no battle cruisers or dreadnoughts, had been surpassed by the Germans as a naval power.

The first French dreadnoughts, the four ships of the Courbet class, were not laid down until late 1910, becoming operational in 1914. These were followed by three superdreadnoughts of the Bretagne type. The navy was stigmatized by several accidents, notably powder detonations that sank two battleships in Toulon, the Iéna on 12 March 1907 and Liberté on 25 September 1911.

The French naval law promulgated on 30 March 1912 set a 1920 goal for a fleet of twenty-eight battleships, ten scout and ten overseas cruisers, fifty-two destroyers, and ninety-four submarines (twenty-five oceanic and sixty-nine coastal). The twenty cruisers were not specifically defined. The French had commissioned twenty-five armored cruisers between 1895 and 1911 but, despite some studies in 1913, never ordered a battle cruiser. In fact, naval officials attempted to sneak battle cruisers into the authorized program by manipulating the definition of “scout” and “overseas” cruiser, but the onset of war negated such efforts.

The British and French began discussions in 1911 for cooperation in case of war. Three conventions were established in January and February 1913. The British would take responsibility for the Pas de Calais, assisted by French destroyers and submarines operating from Dunkirk, Calais, and Boulogne. The western end of the English Channel would be defended by a French cruiser squadron supplemented by four British cruisers. The North Sea would be the responsibility of the British, who reserved the right to strip the Mediterranean of their warships, leaving the western basin under the care of the French but retaining responsibility for the eastern basin. On 27 January 1913 the two powers also established a cooperation agreement to cover the Far East.

Germany declared war on France on 3 August 1914. The Franco-British Convention of 6 August 1914 provided for a new distribution of naval forces. The general direction of operations was left to the British Admiralty, except for the Channel (set in 1913) and in the Mediterranean, where the direction belonged to France, which was to protect traffic in the Mediterranean and Adriatic and monitor the Gibraltar and Suez choke points. Cooperation with British forces was planned, but each nation retained its autonomy when national interests were at stake.

Command Structure

Administration

In 1914 the minister of marine, who was often an admiral and until 1893 was colonial secretary as well, was the navy’s political head and the commander in chief. Housed in the Hôtel de la Marine, on the Place de la Concorde, he was responsible for war preparations. A subsecretary of state supervised finances and administration. On 3 August 1914 Armand Gauthier was as minister replaced by Victor Augagneur. The latter’s successors were Admiral Marie-Jean-Lucien Lacaze on 29 October 1915, Charles Chaumet on 10 August 1917, and Georges Leygues between 16 November 1917 and January 1920. However, it was Admiral Augustin Boué de Lapeyrère, minister between 1909 and 1911, who directed much of the navy’s reorganization. The central administration was formed by a 18 December 1909 decree and consisted of:

• The Central Military Department, with the General Staff and the Fleet Personnel Bureau

• The central directorates of Naval Construction and Naval Artillery and the Central Bureau of Hydrographic Engineering

• The Central Bureau of Maritime Administration

• The Central Bureau of Health

• The Central Directorate of Navigation and Maritime Justice

• Administration of the Establishment for the Disabled

• Administrative Supervision

• The Central Bureau of Maritime Aviation, established on 10 July 1914.

The central offices were in Paris, and each district had local offices.

The Bureau of Naval Construction, organized by a decree of 11 November 1909 included:

• The Central Directorate of Naval Construction, notably including the Technical Service that designed warships and the arsenals responsible for the maintenance and, in some cases, the construction of the fleet

• The Central Directorate of naval artillery

• The Central Bureau of Hydraulic Engineering and Civil Shipping.

The Chief of the General Staff in Paris was essentially the head of the minister’s military cabinet. He ensured the organization of naval forces, their mobilization, and fleet movement, but he did not control operations. This position was occupied by Vice Admirals Louis Pivet (from 20 May 1914), Charles Aubert (7 December 1914), Marie de Fauques de Jonquières (2 May 1915), and Ferdinand De Bon (10 March 1916 to May 1919). The general staff was organized into four sections:

• Section 1: intelligence, foreign navies

• Section 2: bases and support, mobilization, requisition, transportation, and supply

• Section 3: communications

• Section 4: naval forces, operations.

A fifth section, coastal defense, was added on 21 September 1917, and the fourth section absorbed the third in 1916.

Advisory bodies consisted of mainly the Supreme Council of the Navy, supplemented by technical commissions or committees, or administrative commissions, such the commission for new-warship trials, the committee for naval weapon doctrine, the machinery control committee, and the Board of Health. The Supreme Council, which included the admirals at the top of the hierarchy, determined new ship types and the characteristics desired by the navy. The Naval College, which became in 1922 the Naval Graduate College, annually matriculated fifteen to twenty officers who were destined to become general officers, and it constituted a think tank.

The navy’s budgets increased with the threat of war. It was 333 million francs in 1909, 375 million in 1910, 415 million in 1911, 457 million in 1912, 567 million in 1913 (including 222 million for new warships), and more than 600 million francs in 1914 (including 268 million for new construction), in an overall budget of 8.9 billion. Warships under construction at the beginning of the war totaled 257,000 tons.

Command and Fleet Organization

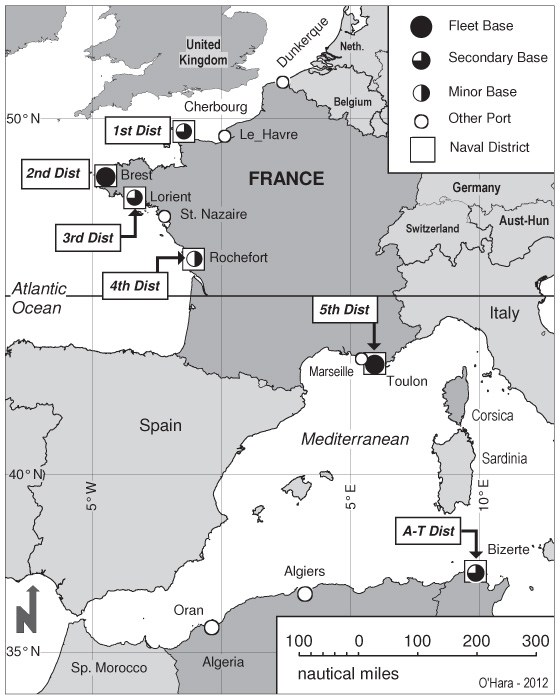

The home fleets (Mediterranean and Atlantic) were each under the orders of a supreme commander, but in reality the main position in the navy was that of the commander of the Toulon battle squadron, in which was concentrated the core of the Mediterranean units. A vice admiral/maritime prefect commanded each maritime district defense and the area’s defense. The maritime prefects and their wartime commanders were:

• Cherbourg (1st District), Vice Admirals Le Pord (1912), Pivet (1914), Favereau (1914), Tracou (1916), Jaurès (1917), and Rouyer (1918)

• Brest (2nd District), Vice Admirals Chocheprat (1911), Berryer (1914), Moreau (1915), Pivet (1915), Le Bris (1917), Moreau (1917), and Salaün (1919)

• Lorient (3rd District), Vice Admirals Perrin (1913), de Gueydon (1916), La Porte (1917), Favereau (1917), and Aubry (1918)

• Rochefort-sur-Mer (4th District), Vice Admirals Amelot (1914), Nicol (1916), and Charlier (1917)

• Toulon (5th District), Vice Admirals Chocheprat (1913), De Marolles (1914), Rouyer (1916), and Lacaze (1917)

• Bizerte (Algerian-Tunisian Maritime District), Vice Admirals Dartige du Fournet (from 1913), Nicol (1915), Auvert (1915), Guépratte (1915), and Darrieus (1918).

Local commands were also located overseas.

The war led to some reorganization, the most notable instance being the creation of the Directorate General for Submarine Warfare (MSB) on 18 June 1917. The order of battle, as of 3 August 1914, comprised elements at Toulon, Brest, and Dunkirk.

In Toulon was the Armée navale (Main Fleet), under Vice Admiral Boué de Lapeyrère, comprising:

• Section hors rang (Independent Section) (Vice Admiral Boué de Lapeyrère): Courbet, one cruiser (Jean Bart after 6 August)

• 1re escadre de ligne (1st Line Squadron) (Vice Admiral Chocheprat): six Danton-class battleships

• 2e escadre de ligne (Vice Admiral Le Bris): five Patrie-class battleships

• Division de complément (supplemental division) (Rear Admiral Guépratte): four old battleships

• 1re division légère (1st Light Division) (Rear Admiral de Ramey de Sugny): four armored cruisers

• 2e division légère (Rear Admiral Sénès): three armored cruisers

• Division spéciale (special division) (Rear Admiral Darrieus): two old cruisers, seven cruisers, one seaplane carrier, three minelayers, three transports

• Flottille de contre-torpilleurs (destroyer flotilla) (Captain Lejay): 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 5th, and 6th escadrilles de contre-torpilleurs (destroyer squadrons); thirty-seven large torpedo boats

• Flottille de sous-marins (submarine flotilla) (Captain Moullé): 1st and 2nd escadrilles de sous-marins (submarine squadrons); six torpedo boats, fifteen submarines.

At Brest was the 2e escadre légère (2nd Light Squadron), under Rear Admiral Rouyer:

• 1re division de croiseurs cuirassés (1st Armored Cruiser Division) (Rear Admiral Rouyer): three armored cruisers

• 2e division de croiseurs cuirassés (Captain La Cannelier): three armored cruisers, one training cruiser

• Division des flottilles (Captain Lavenir): three torpedo boats

• 1st, 2nd, and 3rd escadrilles de torpilleurs d’escadre (fleet torpedo-boat squadrons), groupe de réserve des torpilleurs d’escadre (torpedo-boat squadron reserve): twenty-two torpedo boats, two minelayers

• 1st, 2nd, and 3rd escadrilles de sous-marins: seven torpedo boats, twenty-one submarines.

Finally, there was the Dunkerque Mobile Defenses (Commander Saillard): twenty-two torpedo boats, four fleet minesweepers, and four trawlers. In total, there were 690,000 tons of warships in service at the beginning of the war. The naval forces had been reorganized on 31 October 1911, when three battleships squadrons were formed in the fleet. Beginning in August 1914, the domestic forces were divided into the Main Battle Fleet (l’Armée navale) and the 2nd Light Squadron (2e escadre légère).

The movement to a war footing was gradual. On 26 July 1914 staff was recalled, the operation of schools was suspended, and supplying completed. On 27 July the training divisions were armed. The arming of auxiliary ships began on the 29th. The navy was reinforced by the division de complément (supplemental division) of Admiral Guépratte, which included the battleships Suffren, Saint Louis, Bouvet, and Gaulois; the divisions of Morocco and the Levant; and the training division. The oceanic training division, of six armored cruisers (Marseillaise, Amiral Aube, Jeanne d’Arc, Gloire, Gueydon, and Dupetit Thouars), reinforced the 2nd Light Squadron. The general mobilization order was issued on 1 August.

L’Armée navale was based at Toulon until it was ultimately disbanded in March 1920. The successive commanders, who at the time of mobilization was also the commanders in chief in the Mediterranean, were Admirals Boué de Lapeyrère (beginning on 5 August 1911, on board Courbet from 5 January 1914), Dartige du Fournet (19 October 1915, on board France, then Provence from 23 May 1916), and Gauchet (15 December 1916, on Provence). The 3rd Squadron, or Syrian Division, was created on 5 February 1915 with three old battleships and a cruiser.

Italy’s entry into the war on 24 May 1915 led to the basing of a French Adriatic Division being at Brindisi to reinforce the Italian navy. It had two destroyer flotillas of six units each and a squadron of six submarines. On 20 September 1915 a mixed antisubmarine flotilla was created with six destroyers and ten trawlers. On 1 July 1918 the fleet consisted of the 1st and 2nd Squadrons, one light division, four torpedo boat flotillas, a flotilla of submarines, the Salonika, Syria, and Aegean Sea divisions, and the Provence, Algeria, and Tunisia patrols.

The 2nd Light Squadron was based in Brest. Commanded by Admirals Rouyer and then Favereau, from 27 October 1914, it was dissolved on 15 November 1915. It was partly replaced by the Eastern Channel and North Sea Fleets. The Atlantic Division of Rear Admiral Grout was created on 28 May 1918 to escort American convoys.

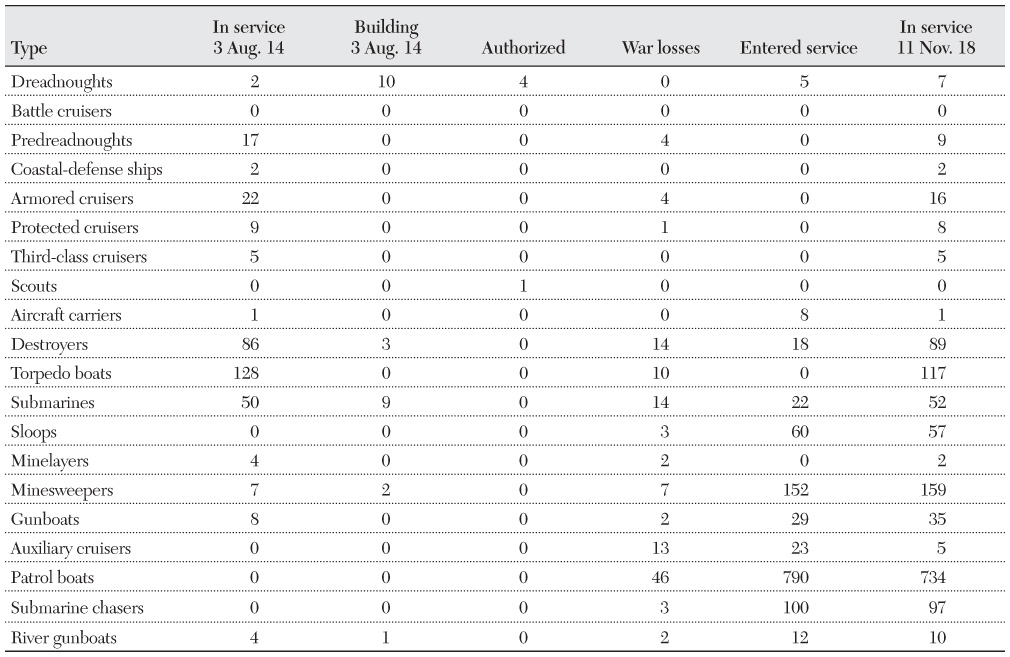

In October 1918 divisions consisting of destroyers and patrol boats operated in the eastern English Channel and North Sea. Naval commands were established in Dunkirk, Calais, Boulogne, Dieppe, and the sea frontiers at Nieuport, Dunkirk, and Calais. (See table 2.1. Some figures are questionable depending on how certain ships are classified, especially third-class cruisers, sloops, and gunboats, whose classification varies according to time and from document to document, even in official papers. Multirole vessels, such as gunboats, minesweepers, and patrol boats, were classified in either category, and figures may be arbitrary, especially for the auxiliaries.)

Many old ships were decommissioned during the war. Thus the number of ships in service on 11 November 1918 does not equal the total of those in service in 3 August 1914 plus newly commissioned ones minus the losses. A portion of the auxiliary cruisers became armed troop transport ships or hospital ships. The Greek warships taken over in 1916 and 1917 are not included.

Communications, Tactical and Strategic

The first tests of radio transmissions (called TSF, for télégraphie sans fil) between warships were conducted in 1900 and onboard installations had became widespread by 1904. The devices were bulky and fragile. Communications were made in written form (Morse code), and transmission time was very long, given the time required for encoding and decoding. Ranges were short. The navy adopted the Marine type 1908 wireless and then a post-1916 model of six kilowatts. A network of listening posts was implemented in 1913 for the interception of foreign transmissions. Small, directional devices were available for shipboard use by late 1915.

Merchant ships were progressively fitted with wireless from 1917. The French went from 101 ships with wireless in early March to 359 by the end of the year and 462 in 1918. Seaplanes, especially those engaged in coastal antisubmarine patrols, were being fitted with transmitters by the end of 1916, but deliveries were very slow and the sets were not very reliable. Aircraft also carried pigeons, which allowed pilots at least to be able to call for help in case of ditching.

Table 2.1 French Warship Strengths and Types

In 1914, overseas connections were provided by cables and radio posts, occasionally by the ships themselves. Tahiti was the only colonial post without cable.

Intelligence

Information on foreign navies was provided by naval attachés stationed in major embassies and consuls in foreign ports. From 1915 the French intelligence services intercepted and decoded German radio transmissions. Lack of liaison between the services concerned (the ministries of War, the Navy, Interior, and Foreign Affairs) meant that the best use of decrypts was not always made. For example, the Ministry of War intercepted and decoded a message from the German army attaché in Turkey announcing that Turkey would join the Triple Alliance on 4 August 1914. The Minister of Marine and the fleet commander, however, were not informed, and the fleet commander proceeded to maneuver against the prospect of Italy’s entry, as he was unaware of its declaration of neutrality.

By 1917 the French were able to decipher submarine traffic with a twelve-hour delay. The presence of submarines was also disclosed by the obvious sinking of a ship by one of them, as well as by conventional optical means (watchers in coastal stations, seaplanes, or balloons), but exploitation was often limited by the small areas patrolled by warships and the modest performance of the weapons available.

Infrastructure, Logistics, and Commerce

Bases

The navy’s main bases were all located in metropolitan France, where industrial support was centered. Toulon, on the Mediterranean, was the main fleet base. Its arsenal, in addition to performing maintenance, constructed small vessels, including submarines. Ten dry docks were in use. La Seyne, which constructed battleships, was across the roadstead from the arsenal. Bizerte was not fully completed in 1914, and the arsenal of Sidi Abdallah, at the base of Lake Bizerte, had only two dry docks. Oran and Algiers in Algeria could supply ships in transit. Torpedo boats were based at Oran.

On the Atlantic coast, Brest was the base of the 2nd Light Squadron, and its arsenal was the navy’s largest industrial establishment. It had eight dry docks. Lorient and Rochefort Harbor contained arsenals; each had two dry docks. Brest and Lorient could build large warships, and Rochefort could construct destroyers. Cherbourg, on the southern Channel, could construct submarines and had eight docks. Most docks were old and small in size, and the length and beam of French dreadnoughts were such that these ships could use only a few of them. A program to build larger docks was completed only after the war.

Naval industrial establishments were also located at Indret (propulsion), Ruelle (artillery), and Guérigny (anchors and chains). In Indochina, Saigon’s small arsenal had a dock. Facilities at distant stations, with limited supply (coal) and support capabilities, were located at Fort de France, Martinique; Casablanca, Morocco (under construction); Dakar, Senegal (with a dry dock); Diego Suarez, Madagascar (with a dry dock); and Papeete, Tahiti. (See map 2.1.)

In the early twentieth century French industry, which relied on the nation’s coal and iron resources, was well developed but still behind that of the Germans, British, and Americans. Industrial organization was convoluted, and there were many small businesses involved. French engineers, in the quest for perfection, conceived sophisticated and complex equipment that was often difficult to maintain. Poor communication between the arsenals and competition among private yards limited industry’s ability to produce units in series.

Large engineering industries, which the arsenals depended upon to equip ships, were concentrated in the northeast and the Paris regions, far from the ships themselves. Industry could not sustain the fleet’s planned expansion, and orders had to be placed abroad. For example, propeller shafts for the battleship Gascogne were subcontracted to Skoda in Austria-Hungary. Ships in service during the war were built in the arsenals and private yards. The warships were constructed in classic fashion—riveted and laid down on traditional slipways. General plans were normally prepared by the Technical Department, but the details were usually left to the shipyard, which led to many differences between ships in the same class. Coal was still the fleet’s main source of energy; oil (38,195 tons consumed in 1914) was only used by submarines and a few destroyers. The total number of men working in the arsenals was 22,000 to 23,000.

The general mobilization of 1 August 1914 disrupted the arsenals with the departure of mobilized workers, since many were registered sailors. At that time, the war was expected to be short. However, as the war continued, it was necessary to reorganize work in factories and arsenals. Industrial facilities were reduced with the German occupation of northern France, and part of the navy’s coal had to be imported from Wales to replace the production of occupied areas. Warship construction stopped during the mobilization, except on those ships whose construction was well under way, such as the three Bretagnes, two destroyers, and submarines. In fact, the arsenals were mainly engaged in helping offset the army’s lack of heavy artillery; they would ultimately provide 8,500 guns, including 1,500 new large-caliber weapons, complete with ammunition. The navy also sold all its heavy guns available to the army.

Construction of surface combatants resumed in 1916, totaling 80,000 tons of patrol vessels. It remained for foreign builders to take up more demanding projects, and a dozen 685-ton ships were ordered from Japan in 1917. The Americans supplied a hundred submarine chasers, while the British provided some sloops. The French navy, which began the war with 690,000 tons of warships in service, came to 11 November 1918 reduced to 652,000 tons, though with 129,600 tons under construction.

Shipping (Sea Routes and Traffic)

In August 1914 French shipping totaled 2,556,000 tons, including 1,745,000 tons of steamships (about a thousand ships) and 701,530 tons of sailing vessels, including 150 “tall ships” (as known today, the “Cape Horners”) and 500 transports. At the end of 1913 there were 29,296 fishing vessels, totaling 271,000 tons, of which 356 were steam powered, 43 were motor, and 27,507 under sail. The construction of a fleet of sailing trawlers was funded and bonuses awarded after 1906 to expedite the construction of domestic warships with steam power. Private companies, often state supported, conducted most of the commercial maritime traffic between the métropole and the colonies. Three of these, the Compagnie Générale Transatlantique, the Messageries Maritimes, and Chargeurs Réunies, together owned more than 800,000 tons of shipping.

In addition to the shipping lines to North and South America and the West Indies, most of the traffic from metropolitan France was concentrated in three major shipping routes to North Africa, to West and Equatorial Africa, and through the Suez Canal to Indochina and the Far East.

During the war, requisitioned ships supported the army and naval forces engaged in the eastern Mediterranean. These vessels were fitted out as hospital ships or troop carriers, sometimes switching from one function to another. Initial requisitions included four auxiliary cruisers, over fifty tugs, and two hundred trawlers.

The Maritime Transport Committee was created on 29 February 1916. Shipping was transferred from the Department of the Navy to the Department of Public Works, Transport, and Supply in December 1916, after the creation of a Directorate General for Transportation and Imports on 18 November 1916. A decree of 22 December 1917 brought all French commercial vessels under the orders of the state, and an order of general requisition was finally issued on 15 February 1918.

During the war, the merchant navy lost 3,200 men and 1,128,000 tons of shipping, including 921,000 to enemy action. Losses consisted of 280 steamers (712,000 tons) and 431 sailing vessels.

Demographics

On the eve of the war, the navy had 2,850 officers and 62,600 enlisted men. The proportion of officers was 4.4 percent of total personnel. Reservists were called up during mobilization. Crews of the active fleet were brought to wartime levels, and requisitioned ships were manned; some, in fact, were requisitioned complete with crews. Only 30,000 of the 121,500 men initially drafted were enlisted into the navy; the others were retained at their posts or were considered unfit for service for various reasons, such as illiteracy. Draftees were brought into service slowly, to avoid congestion, and mobilization was not completed until 1 March 1915. Surplus personnel were ultimately transferred to the army. At the armistice the navy had 155,000 men in service.

Training

Naval officers were trained at the Naval Academy (École Navale) in Brest after passing a competitive entrance examination. Studies, which were often considered too theoretical, ran two years on Borda, an old ship anchored in Brest Harbor, followed by almost ten months on a training ship, which in 1914 was the armored cruiser Jeanne d’Arc. These officers might serve within a chain of command or as commanders of smaller warships. Then, after attendance at the Naval War College (l’École supérieure de marine), and toward the ends of their careers, they became the captains of major warships. Other officer graduates of the special schools were distinguished by their specialties, such as engineering, health, supply, naval construction, hydrographics, navigation, and naval artillery. The technicians in maritime engineering were responsible for the construction of warships. They were assisted by officers in that course of study (future engineers).

There were so many officers that progress up the ranks was slow. Lieutenants remained long in their grade, and some were assigned to land positions often held by civilians in other major navies. The proportion of junior officers was higher than in other navies, while the proportion of senior officers was lower. The latter were usually older than their foreign equivalents; a battleship commander was at least fifty-four years of age, ten years older than his British or German counterpart. The rank of lieutenant commander (capitaine de corvette), suppressed since 1848, was restored on 1 July 1917.

Officer training was shortened during the war. An applied school (École des chefs de quart) was opened at Lorient for Naval College candidates and students from the merchant marine who had enlisted or been mobilized. They underwent a course of several months’ training in essential practical manners. After the war Lorient returned to being a training school for officers. Many reserve officers, usually from the merchant marine, took positions with the Fleet Auxiliary, including patrol duty, with ships still manned by their premobilization crews.

Petty officers (NCOs), quartermasters, and sailors were groups within the body of the crews of the fleet. There were six main specialties: helmsmen-seamen, gunners, torpedoes, marines, mechanics and stokers, and electricians. This list was supplemented by specialties less “naval” in character, such as steward. Petty officers were usually recruited from the ranks and trained in schools of specialization. Grades ranged from first master to second master.

Sailors were either enlisted (a youth could enter the École des Mousses from age fourteen) or conscripts from the naval draft, a feature dating back to Colbert that mobilized young merchant seamen, fishermen, and arsenal workers for the navy. The time of compulsory military service was three years in 1914. In 1906 half of the navy’s needs were covered by the naval draft, the rest by enlisted volunteers—more than 80 percent from the coastal departments. Many enlisted men were from Brittany.

Schools were closed during mobilization, but as the war continued the French needed to reopen the School of Apprentice Mechanics in Lorient, which was done on 2 March 1915. The courses were accelerated, and practice then usually became “on the job.”

Culture

A large proportion of officers came from the upper classes of society. Often described as conservative, they had a reputation for resistance to change. Outside of headquarters assignments and service in Paris, they lived in the five major metropolitan ports, somewhat isolated on board ship or together in naval housing. The weight of tradition was strong, an acculturation partly acquired during training at the Naval Academy.

On-board accommodations, lifestyle, food, and education all formed barriers between officers and crew. A comparable barrier also existed, despite often a common origin, between the petty officers and sailors. Symbolic of social organization on board was the organization of the wardrooms (officers) and mess halls (petty officers and crew); on large ships there were no less than six messes: admiral, senior officers, junior officers, petty officers, junior petty officers and medical staff, and crew. Outside of coastal areas, the navy was often ignored and at best poorly understood by the French, the majority of whom were farmers.

Surface Warfare

Doctrine

After many metamorphoses, especially because of the Jeune École, a surface warfare doctrine supported by the Naval Graduate College eventually won the approval of the minister and Parliament. Alfred Thayer Mahan’s influence was obvious when the French finally abandoned the doctrine of the guerre de course (war against commerce) in favor of a guerre d’escadre (squadron warfare) strategy based on the main fleet, although the obsession with coastal defense remained. The goal of the new naval strategy was a decisive clash between battle fleets, clearly along the lines of fleet actions like Trafalgar (ideally with better results, from the French point of view) and Tsushima. The result was a unique main-battle force, l’Armée navale, most of the strength of which was under the command of an amiralissime, a commander in chief equivalent to the army’s general of the army. The political situation (and the power of the new German navy, with which a direct confrontation was impossible without British support) led, after an agreement with the British, to the concentration of naval forces in the western Mediterranean.

The navy was in disagreement with the army and its policies, which obviously were mainly concerned with the land front in the event of conflict with Germany. The army’s plans required that the navy’s first duty, upon the outbreak of war, was to cover the passage from North Africa to France of the 19th Corps (38,000 men, 6,800 horses—the divisions of Algiers, Oran, and Constantine—in forty-six ships) and troops from Morocco (11,000 men and 5,000 horses in forty-three ships). The presence of these troops was deemed essential to the Northeastern front for the anticipated great battle with the German army.

Ships/Weapons

The priority given to the battle fleet led to development of the divisions of battleships. In thus passing from one developmental extreme to the other, the French navy came late to the dreadnought race and neglected its light scouting forces.

Battleships

The five 15,000-ton battleships of the Patrie class (the sixth, Liberté, blew up in 1911) were classic predreadnoughts, with four 305-mm main guns and a secondary battery of eighteen 164-mm (Patrie, République) or ten 194-mm (Démocratie, Vérité, Liberté, Justice) guns. They were completed between 1906 and 1908.

The six 18,000-ton battleships of the Danton class (Danton, Mirabeau, Diderot, Condorcet, Vergniaud, Voltaire), described as “semidreadnoughts,” were laid down between 1907 and 1908. They carried four 305-mm and twelve 240-mm guns and had turbine propulsion. The dual caliber was upheld by the Supreme Council of the Navy because it could deliver the same amount of a metal per single barrel a minute as the larger caliber, thanks to its higher rate of fire. This would permit a veritable blasting of the enemy’s superstructure at the then-current combat ranges of only six thousand meters.

The first French dreadnoughts were the four Courbets, which became operational in 1914. They displaced 23,500 tons and carried twelve 305-mm guns. Upon mobilization the dreadnoughts Courbet and Jean Bart were operational, followed by Paris on 9 September, then France on 18 October. These ships suffered from teething troubles, particularly jamming of the main gunnery breeches after just a few shots. The class was followed by three Bretagne-class superdreadnoughts (Bretagne, Provence, and Lorraine), a simple adaptation of Courbet with ten 340-mm guns. Though laid down in 1912 and their construction well advanced in 1914, they would not be completed until 1916. Five battleships of the Normandy class were laid down in 1913, but construction stopped at the beginning of the war. Their twelve 340-mm guns were installed in three quadruple turrets of the same model as before. This same turret would also have fitted out the four units of the Lyon class (four turrets) that should have been started in 1915. The other battleships in service were obsolete predreadnoughts, even though the last six, and Danton, were in service for three years.

Cruisers

The fleet lacked modern light scout cruisers to guard the flanks of the battleship divisions. A design for an escort (scout) of 4,500 tons was planned for 1915, but the war forced the project’s abandonment. Battle cruisers were studied in 1913, but none were ordered before the war.

The twenty-five armored cruisers in service in 1914 had all been built after 1888. The newest was Waldeck Rousseau, laid down in 1906 and completed in 1910. All these ships were too big, too poorly armed (194-mm batteries), and too slow (twenty-three knots) to perform the role of scout. The remaining fifteen protected and unprotected cruisers were too old (about fifteen years) and too limited in performance for fleet use. In 1914 the navy did not possess the right type of cruiser for a fleet squadron. Its armored cruisers were outdated but at least had the advantage of an imposing appearance, with their four or six funnels, as well as significant mission performance capability.1

Torpedo Boats

In 1914 the navy still had more than a hundred numbered coastal torpedo boats, as a consequence of its past adherence to the doctrine of Jeune École. They served as escorts and patrol boats until the specialized ships that were being hastily put into construction arrived. In some cases propulsion plants were stripped from disarmed torpedo boats to equip Ardent-class gunboats built from 1916.

French destroyers comparable to their British counterparts appeared in 1899, with the commissioning of the first three-hundred-ton vessels of the Durandal class. In 1914 there were three torpedo gunboats of the d’Iberville class, of about nine hundred tons and dating from the 1890s, which were sometimes classified as contre-torpilleurs (destroyers). French contre-torpilleurs were reclassified as torpilleurs de haute mer (oceanic torpedo boats) on 14 March 1913. The term contre-torpilleur did not reappear for ships until the Jaguar program in 1922 but was still used in the designation of formations.

In 1914 the majority of French destroyers were three-hundred-ton types, of which fifty-five units were constructed between 1900 and 1908. They were obsolete by 1914 and unsuitable as escorts. In August 1914 twenty-nine were in the Atlantic, twenty-one in the Mediterranean, and three in Indochina. Thirteen 450-ton torpedo boats were completed between 1909 and 1912. The construction of eight-hundred-ton torpedo boats started in 1910; sixteen were in service when the war started; two followed shortly thereafter and two more of 850 tons in 1916. A design for a 1,500-ton destroyer was adopted in January 1914 but was not realized until 1922.

On 9 August 1914, the French requisitioned four 990-ton ships under construction for export to Argentina, commissioning them by year’s end, but this did not give the navy enough large destroyers to screen the fleet even in good conditions, a problem aggravated by the need to counter the submarine threat. The seizure of twenty Greek destroyers and torpedo boats in December 1916 also gave only partial relief. Given the limits on wartime shipbuilding, the French found the situation so serious that they resorted to ordering a dozen 685-ton ships from Japan in 1917. The rest of the fleet, in addition to submarines, consisted of a collection of old ships, some of them posted overseas (gunboats, transports, auxiliaries).

Weapons

Gunnery had been improved since 1906. A corps of naval artillery engineers succeeded the colonial artillery engineers in 1909. A controlling department for powder was set up after the explosions of Iéna and Liberté.

In 1914 the gun calibers in use were 305-mm (in six models), 274-mm (the old battleships), 240-mm (Danton’s secondary battery), 194-mm (gunnery school, old battleships, and armored cruisers’ main batteries), 164.7-mm, 138.6-mm (at the time referred to as “14 centimeters”), and 100-, 75-, 65-, and 47-mm. The best of these was the 240-mm cannon. Guns of 75-, 90-, and-120-mm were supplied by the War Department to equip a portion of the auxiliary fleet.

Sailors and engineers considered that a battle could not be fought at ranges greater than twelve or thirteen thousand meters. The ranges of guns were thus intentionally limited, with low elevation angles for the heavy guns and a plethora of secondary batteries. Range finders and fire control were poor; English Barr & Stroud range finders were purchased at the beginning of the war. The navy did not increase elevations until 1916, after it learned that the 305-mm guns of the Austro-Hungarian fleet could range to 20,000 meters. The superdreadnought Provence was commissioned with one of her five 340-mm turrets capable of shooting 21,000 meters instead of 14,500. Torpedoes were originally purchased from Whitehead, Fiume, and were constructed in part at Toulon from 1894. A factory was still incomplete in Saint-Tropez in 1914. Weapons in service were of 356-, 381-, and 450-mm calibers. The first two sizes armed torpedo boats and the first contre-torpilleurs. The 450-mm caliber dated from 1892, and five models were in use on the latest destroyers. The 450-mm Model 1906 weighed 648 pounds and had an 86.8-kg warhead. It ranged to 600 meters at 36.5 knots, 1,000 meters at 32.5 knots, 1,500 meters at 27 knots, or 2,000 meters at 24.5 knots.

Offensive

Doctrine

The mission of French submarines was initially to protect harbor approaches, acting defensively toward friendly vessels and offensively against enemies. In 1912 it was planned to have them participate in the guerre d’escadre. A division of three submarines, led by a three-hundred-ton torpedo boat, would scout ahead of the fleet and then deploy in front of enemy warships. Submarine squadrons would screen the flanks of the battle fleet, but the low speed of the boats, around twelve knots, made the practice of such tactics very difficult, and they were never applied. During the war, submarines were initially used in a static role to monitor enemy ports in the Adriatic and to form patrol lines in the Channel blockade. This changed when they were assigned an antisubmarine-warfare role and began hunting for enemy submarines.

Boats/Weapons

Overall, French boats were relatively inefficient and fragile. Engineers had created systems that were too complex, difficult to maintain, and ill suited to war service. The systems were too precise for the techniques of the time. The admirals were generally skeptical about the capabilities of the submarine arm, there was no central office or research bureau, private industry was not interested, and there was no coordination. The training of personnel, selected from volunteers, could not make up for the poor design of their craft. Industry could barely make reliable diesel engines, for which the market was so small; therefore, part of the fleet needed to be equipped with a steam engine for surface propulsion, with a diving time (for over ten minutes) incompatible with military necessity.

Operationally, the submarines were divided between offensive units (the more efficient) and defensive (the older submarines), which were placed in ambush positions along the coastal zone. The best submarines were the seventeen steam-driven units of the Pluviôse class completed between 1908 and 1911 and the thirteen diesel boats of the Brumaire class completed between 1911 and 1912.

The navy had fifty submarines readily operational in August 1914 (the figures vary between thirty-four and sixty-two, depending on how one defines availability). In early August 1914 submarines were deployed as follows:

• The English Channel, with:

– The 1st Squadron at Cherbourg with eleven boats.

– The 2nd Squadron at Calais with eleven diesel-powered boats.

– The 1st Squadron at Toulon with seven stream-powered submarines.

– The 2nd Squadron at Bizerte with eight diesel submarines.

Nine relatively old boats were assigned to the defense of Cherbourg (four) Toulon (two), and Bizerte (three).

Antisubmarine

In 1914 the concept of antisubmarine warfare was still unclear. The possibilities of submarines had been poorly understood. When on the surface, submarines could be attacked from above or hit by gunfire, but underwater they were virtually undetectable unless revealed by a their own torpedo or periscope.

The first antisubmarine depth charges, which the navy began developing in 1914, were released by a surface vessel, which needed to pass just above the submarine. These first depth charges contained thirty kilograms of gun cotton. Five hundred were constructed, followed in 1915 by depth charges of the Guiraud design, weighing forty-five kilograms with a charge of twenty-five kilograms. A first order was for four thousand, and in 1916 each patrol boat carried six. Depth charges of the naval artillery type with 40-, 45-, and 75-kg of explosives were also ordered in 1916 and 1917. Four thousand CM-type depth charges were delivered in late 1917. They had warheads with thirty-five kilograms of melinite. It was not until 1918 that launching equipment, such as depth charge throwers and mortars, were being shipped in sufficient numbers. By 1916 a towed antisubmarine sweep, the Marseillaise device, was also in service.

Seaplanes engaged in antisubmarine warfare did not have effective weapons. They typically used a twenty-two-kilogram bomb, type D, containing eleven kilograms of melinite. It was dropped from an altitude of one or two hundred meters and exploded at a depth of eight meters. A 47-mm gun fitted to a hundred seaplanes was in service by early 1918.

Submarines were noisy while underwater, and detection was possible by listening for them using a device derived from a stethoscope, but the hunting vessel needed to be stopped. Lieutenant Walser developed a device with acoustic resonators contained in two spherical caps. It could be used at speeds of up to six knots and could give an approximate bearing. It was tried in March 1918 and then mounted on board a hundred warships. Active detection by ultrasound echoes, tested from late 1917 by Professor Langevin, arrived too late for the war. The most common listening device was the Perrin microphone, a simple underwater microphone that required the listening vessel to be at a standstill in order to detect a submarine. This equipped all antisubmarine vessels too small to carry a Walser apparatus.

Mine Warfare

Doctrine

The navy had no real mine-warfare policy. Mines were mostly intended for defensive barriers off ports. Minefields were supplemented by fixed torpedo tubes, including the defense of the Brest Narrows. Despite this, France laid fields within certain anchorages in the English Channel and North Sea, off the Turkish coast, and on the Atlantic side in areas where submarines could operate. France participated in the construction of the Otranto barrier in 1918 with nets and mines. Throughout the war the French navy did not lay more than 4,700 mines.

Ships/Weapons

The Ronarc’h drag method of sweeping—a sweep of two cables in the form of a large V held out by underwater kites—was tested in 1910, then adopted and widely used during the war. The number of sweepers increased with the requisition of new craft, growing from about thirty sweepers upon mobilization to seventy-six in November 1915 and 228 by the end of 1916, then dropping to 110 in July 1918. The number of sweepers rose again to 248 after the armistice to clear mined areas.

Minelaying was carried out by two old torpedo cruisers, Casabianca and Cassini; by two small specialized ships launched in 1913, Cerberus and Pluton; and by destroyers equipped with rails. For sweeping, the navy used four minesweepers built in 1913, but most sweepers used during the war were tugs and requisitioned auxiliaries. Torpedo boats, gunboats, and sloops built during the war were also equipped for sweeping.

In 1911 the stock consisted of 2,800 mines, of which only the 1,500 of the model 1906 were not totally obsolete. All mines were contact types. The principal mines were, in addition to the model 1906, Breguet, Sauter-Harle, and the Schneider, for two submarine minelayers completed in 1918.

Amphibious Warfare

Doctrine/Capabilities

Marines represented a specialty within the regular navy, such as engineering or torpedoes, not a separate force as in the U.S. and British navies. Each ship had a team of sailors led by regular officers trained to form a landing company in case intervention ashore was required. Landings were usually accomplished using the ship’s boats.

A doctrine for amphibious operations had not yet been codified, and the concept was limited to the notion of a coup de main by the companies landed. There were no specialized ships for landing operations; in the event of need, amphibious transports would consist of commandeered ships, especially already-armed auxiliary cruisers.

Coastal Defense

The coastal-defense system was the legacy of the British threat against the French coasts. Controversy between the ministries of the Navy and War (which included the army) led to a shared responsibility for coastal defense, with the navy in charge of Cherbourg, Brest, Toulon, and Bizerte, the Ministry of War of all other coastal zones.

From late August 1914 the Ministry of War began to disarm some of its coastal batteries to recover the guns for use on the land front, due to a lack of heavy artillery. The growing threat of submarines led to a meeting on 12 February 1917 and the decision to strengthen coastal defense with medium-caliber rapid-fire guns, and a decree of 21 September 1917 assigned coastal-defense responsibility to the navy. The mission was entrusted to the Fifth Section (EMG 5) of the navy’s General Staff. By the end of 1917, fifty-five defense posts had been installed by the army and armed with the help of the navy, each with two 90-, 95-, or 100-mm guns.

Naval Forces Ashore

From 12 August 1914, as in 1870, surplus sailors available after mobilization were gathered into battalions designed to ensure the safety of Paris. They were finally sent to reinforce the front; two regiments forming the Brigade of Marines were committed from 16 October to 10 November 1914 in Dixmude, Flanders, where they stopped the German advance. The brigade was disbanded 22 November 1915 and replaced by the Bataillon de marche des fusiliers marins, which fought until the armistice.

Spare 37-mm guns armed twenty-six armored-car sections from late September 1914, and eleven sections of light cars were allocated to the army, but the sailors who manned them were recovered by the navy beginning in 1916. The navy was also required to send to the land front gunners to man heavy artillery batteries (305-, 194-, and especially 164-mm), the number of which reached eighteen by 1918, and also, from 1916, to man on the river system a dozen barges armed with a 138- or 100-mm weapons.

The navy developed its first aircraft at the end of 1910. The Department of Naval Aviation was created by decree on 20 March 1912, and the Central Bureau of Naval Aviation was organized by a decree of 10 July 1914. A former torpedo cruiser (another legacy of the Jeune École), the Foudre, was refurbished in 1911 and used for tests and maneuvers with seaplanes on board. The first flight of an aircraft was made from a forward platform on 8 May 1914, but the war interrupted the development of this technique. At the beginning of the war the navy had seventeen aircraft with fourteen pilots, the seaplane carrier Foudre, and a shore base in St. Raphael.

WAR EXPERIENCE AND EVOLUTION

Wartime Evolution

Surface Warfare

Upon the outbreak of war the navy’s first priority was providing complete coverage for the transports bringing troops from North Africa to the mainland. The original plan called for the transports to operate separately in order to avoid losing time, with distant cover provided by a special division allocated to the task, while l’Armée navale was ordered to stop the two German ships in the Mediterranean, the battle cruiser Goeben and light cruiser Breslau. The fleet sailed from Toulon on 3 August 3 at 0400 hours. However, it had only one dreadnought, the Courbet. The announcement of the bombardment of Philippeville by Goeben and of Bône by Breslau early on 4 August disrupted these plans, and the troop transports were then collected into three escorted convoys. Three battleships were detached to search for the Germans before escorting the two dreadnoughts Jean Bart and France from Brest to Toulon, as the second was still undergoing trials and had no ammunition. Courbet was at least 250 miles from the enemy, the French ships were too slow to catch up with the Germans, and no cruisers were fast enough to maintain contact. L’Armée navale covered the transports until 7 August, when the ships left Toulon, this time with Courbet and Jean Bart, and headed to a rallying point at Malta.

Austria Hungary entered the war against France on 11 August. The battle fleet no longer needed to account for the Italian fleet, as Rome had declared its neutrality, and instead the French sought to bring the Austrian fleet to battle. On 16 August the battle fleet was concentrated when it intercepted just off Antivari the small Austrian cruiser Zenta and the destroyer Ulan. The latter managed to escape and took refuge in Cattaro, but Zenta was shot up by the guns of the French battleships. The incident revealed a certain lack of coordination between the French warships.

The Austrian fleet remained out of reach in the upper Adriatic. Now based in Malta, l’Armée navale, ready for the expected battle, implemented a close naval blockade of the Austro-Hungarian navy by maintaining a cruiser in the Strait of Otranto. While the government asked him to act against ships and Austrian ports, Admiral Lapeyrère had always hoped for a face to face confrontation with the enemy fleet. However, the fine workings of guerre d’escadre and squadron warfare was now thrown off by the appearance of the submarine. The torpedoing of Jean Bart, damaged on 21 December 1914, and of the armored cruiser Leon Gambetta, sunk on 27 April 1915, led the fleet to retreat to Malta, and the blockade was then carried out by light vessels. The entry of Italy into the war on 24 May 1915 placed the navy in the second line behind the Italians.

Malta served as the advanced base, while Toulon remained the base for major maintenance. The navy was quickly reinforced by the dreadnoughts Paris and France and in 1916 by the three superdreadnoughts of the Bretagne class: on 7 May Provence, Bretagne on 18 May, and Lorraine on 9 August. This force stood ready to strengthen the Italians should the Austrians attempt to sortie. That fleet, however, generally remained at anchor, successively based at Navarino until the end of 1914, at Corfu from January 1916, and Corfu and Argostoli from April 1916. Its outings were limited to forays into the lower Adriatic.

The main fleet lost some of its forces to peripheral operations. The most important was that of the Dardanelles. The British monitored the outlet of the straits from which the Goeben could appear at any time. Two battleships, Suffren and Vérité, were detached to Tenedos and put under British orders on 27 September 1914. On 29 October Turkey attacked Russia in the Black Sea. On 3 November Suffren and Vérité, along with the British battle cruisers Indefatigable and Indomitable, conducted the first bombardment of the Turkish forts at the entrance of the straits. War was declared on 5 November. A second operation was conducted on 19 February 1915. The allied fleet assembled a battle cruiser and eighteen battleships, including five French ships of the division commanded by Rear Admiral Guépratte (Suffren, Bouvet, Gaulois, Charlemagne, and Saint Louis). A new bombardment was conducted on 25 February.

A purely naval attempt to force the Dardanelles began on 18 March 1915 but failed, with the loss of the French battleship Bouvet and the British Ocean and Irresistible. Battleships Suffren and Gaulois were badly damaged, and the latter was only just saved. Bouvet struck a mine, capsized, and sank in less than a minute. This failure affected the navy, which would thereafter refuse nearly all efforts against coastal defenses until the Second World War. On 25 April the allies landed at the entrance of the Dardanelles, a French brigade being put ashore at Kum-Kaleh, on the Asian side. In the face of Turkish resistance, the allies were finally reembarked on 9 January 1916. The Dardanelles French squadron was renamed the Fourth Squadron on 1 January 1916 and was disbanded in March 1916 with its ships joining the Naval Division of the East in June 1916.

The navy was involved in the defense of the Suez Canal during the Turkish attack on the night of 2 February 1915. The bombardments by the coastal battleship Requin and the cruiser D’Entrecasteaux were decisive. Operating out of Port Said, French ships blockaded the Turkish coast in the eastern Mediterranean. The French occupied Ruad Island on 1 September 1915 and Castelorizo on 28 December. On 12 September 1915 French vessels embarked three thousand Armenian refugees being hounded by the Turks near the northern tip of Ras Al Mina. Two armored cruisers participated in Red Sea patrols in 1915.

In the Far East, the armored cruiser Dupleix was involved in hunting Admiral Spee’s East Asian squadron. The torpedo boat Mousquet was sunk by Emden at Penang on 28 October 1914. The armored cruiser Montcalm acted as an escort in the Indian Ocean. French ships also engaged in the initial operations against Cameroon in September 1914.

In the Mediterranean, the navy supported the Serbian army. Naval 14-cm guns participated in the defense of Belgrade in November 1914. French warships evacuated the Serbian army to Corfu in January 1916 and in April and May 1916 transferred it to Salonika, which the allies had occupied on 5 October 1915.

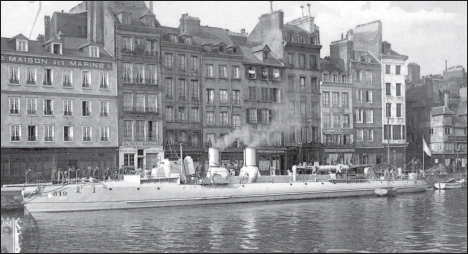

Photo 2.4. Torpilleur 319 (Jean Moulin collection)

War with Bulgaria and, especially, a complicated relationship with Greece led to the creation of the 1st Franco-British Special Squadron between 25 November and 22 December 1915. Later, in late August 1916, a second squadron was activated. On 1 December the landing of 2,900 men at Athens led to gunfire and fifty-four French deaths. Fire from the battleship Mirabeau stopped the Greeks. Eventually, after some complications, and like it or not, Athens joined the allies on 21 June 1917. Meanwhile, the navy seized many Greek ships, including seventeen destroyers.

Armored and auxiliary cruisers of the 2nd Light Squadron maintained a blockade line at the western entrance of the English Channel until April 1915 before being replaced by light warships and auxiliaries. Pas de Calais was guarded by destroyers and submarines until December 1914.

A naval command under Vice Admiral Ronarc’h was established on 1 May 1916 to support the Dover Patrol. This command had a dozen destroyers, a squadron of submarines, and a naval aviation center. Part of its mission was to block the Straits of Dover to German submarines operating from Flanders. There were a few skirmishes with German forces off Flanders, and the torpedo boat Bouclier sank the German torpedo boat A 7 on 21 March 1918.

The French armored cruisers operating from Brest were relatively underutilized and in early 1916 formed two new divisions, one in Dakar and the other in the Caribbean, to address the threat of German surface raiders. In fact, from 1915 the threat of submarines was what guided the deployment of these warships.

Although the fleet was supported by four dreadnoughts in late 1914 and three superdreadnoughts by 1916, no new cruisers were constructed. Four large destroyers of 990 tons being built for Argentina were requisitioned on 9 August 1914 and commissioned in October and November 1914, and twelve 685-ton destroyers were constructed in Japan in 1917. Two eight-hundred-ton torpedo boats (Enseigne Roux and Mécanicien Principal Lestin) were completed in 1916. Twenty-four submarines were completed, including three boats being built for export, along with one more captured from Germany (UB 26 became Roland Morillot).

The most spectacular development was in the patrol and escort fleet, which in November 1918 totaled 111 torpedo boats and destroyers, 63 sloops, 153 patrol boats and submarine chasers, and 734 armed trawlers. The navy lost four battleships (Bouvet mined on 18 March, 1915, Gaulois torpedoed 27 October 1916, Suffren torpedoed 26 November 1916, Danton torpedoed 19 March 1917); five cruisers (Léon Gambetta torpedoed 27 April 1915, Amiral Charner torpedoed 8 February 1916, Kléber mined on 27 June 1917, Châteaurenault torpedoed 14 December 1917, and Dupetit Thouars torpedoed 7 August 1918); twenty-three destroyers, thirteen submarines, three sloops, eight-six patrol boats, requisitioned trawlers and submarines chasers, and eight auxiliary cruisers.

Submarines

The submarine division based at Calais was initially to oppose any attempt by the German fleet to force the Pas de Calais. Two mine barrages were located at Pas de Calais and between Le Havre and Portsmouth. After the appearance of enemy submarines in the English Channel, French submarines were kept in port to avoid confusion and were posted to Dunkirk in 1916 to defend the coast of Flanders and then in 1917 to Brest. Submarines were also towed underwater by sailing vessels as U-boat traps but, sadly, to no avail.

The submarines of l’Armée navale followed it to Malta and then later to the Greek anchorages. They operated in the Adriatic; however, to do so their range needed to be increased, so they were first towed to the Strait of Otranto by a cruiser. The French lost Curie in the Adriatic on 25 December 1914 while attempting to force Pola, Fresnel on 5 December 1915, Monge on 28 December 1915, Foucault on 15 September 1916 to aircraft bombs, Bernoulli mined on 15 February 1918, and Circe to a torpedo on 20 September 1918.

Six submarines were sent to the Dardanelles in October 1914. Only the Turquoise succeeded in operating (for ten days) in the Sea of Marmara; she ran aground and was captured by the Turks on 30 October 1915. The others did not manage to pass through the straits, and three were lost: Saphir 15 January 1915, Joule 2 May 1915, and Mariotte on 26 July 1915.

Six submarines were based at Brindisi in 1915, and a squadron was established in Morocco in 1917. Another squadron was created in Bizerte on 17 June 1917, with five submarines. In 1917 and 1918 submarines were deployed operating from the Atlantic coastal ports to confront their German counterparts and to cover American convoys, in cooperation with maritime aviation. The ability of French submarines to receive messages while submerged allowed greater control over their operations. Submarines were also based in Brest, Gibraltar, and Bizerte to monitor the Sicilian Channel. The results of their operations were small. Four submarines were lost outside the Adriatic Sea and the Dardanelles: the Ariane torpedoed off Bizerte on 19 June 1917, Diane disappeared in the Atlantic 11 February 1918, and Prairial and Floreal in collisions on 29 April and 2 August 1918.

French submarines had limited success. They sank four and damaged three Austrian warships. The torpedo boat Bisson sank the Austrian submarine U 3 on 13 July 1915, and the submarine Circe sank the German UC 24 on 24 May 1917. Statistics kept between 2 August 1914 and 1 January 1918 established that the percentage of nonavailability was 31 percent for steam submarines and 42 percent for the diesel boats. The average proportion of time spent on war cruises was only 9 percent. French submarines conducted nearly four thousand patrols, but these were all short-range. The navy had sixty-four submarines by the armistice, but twenty-two had reduced crews. French submarines were excluded from the battle line, contrary to prewar intentions.

The fight against German and Austro-Hungarian submarines became increasingly important. Weapons and detection equipment, however, were developed relatively slowly. Antisubmarine defense was initially restricted to the direct escort of valuable ships only. Then, in June 1915, two patrol flotillas were established on the ocean and in the Mediterranean.

In late 1915 the allies established a system of patrol routes, first in the Mediterranean, which was divided into eighteen zones—four British, four French, and ten Italian—and then in the English Channel. The navy began arming the merchant fleet in 1915, typically with 90-mm guns provided by the Ministry of War. Ships armed with guns also had special gun crews and were called AMBC ships (armement militaire des bâtiments de commerce, military-armed merchant vessels). By 16 December 1916, 418 ships were thus armed, a number that rose to 591 steamships and 137 sailing vessels by 31 December 1917, and finally to 1,140 by the end of 1918.

The French navy requisitioned 280 patrol vessels, and the fleet was expanded through purchases and orders, especially abroad. The French purchased trawlers from Belgium, Brazil, Greece, Iceland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, Sweden, Spain, and the United States. Thirty-seven antisubmarine vessels were commissioned from French shipyards, and a hundred were constructed in the United States, but only eight of the latter were in service by the armistice.

Patrolled routes were widespread in the Mediterranean in 1916 but proved to be a failure. In March 1917 the number of patrol squadrons was increased from nineteen to twenty-five, including twelve in the Mediterranean. The real solution was the escorted convoy, which was finally implemented in early 1917 for slow cargo ships bringing coal from Wales to France, in May 1917 in the Mediterranean, and finally along the Atlantic coast in June 1917.

By October 1917 nine patrol divisions were in place in the North Sea, eastern Channel, western Channel, Brittany, Gascony, Algeria, Tunisia, eastern Mediterranean, and off Provence. These divisions came under the orders of the maritime prefects on 30 December 1917.

Aviation

The development of aviation and maritime airships was linked to submarine warfare. Several maritime aviation development programs were approved in January 1916. Aviation detachments were located from mid-1916 on all coasts, organized into Centers of Maritime Aviation (centre d’aviation maritime, or CAM) with eight to twelve aircraft, and combat stations (poste de combat, or PC) with a maximum of six units. At the end of 1916, ten centers were located from Dunkirk to Salonika. Development accelerated in 1918, and by the armistice the navy operated thirty-seven CAMs and twenty-four PCs, of which three centers were transferred to the Americans. The Maritime Air Station (L’Aérostation maritime, or balloon division) began arming airships from December 1915. Ten centers were equipped in metropolitan France, three in North Africa, and one on Corfu.

At the armistice the naval air section had 1,264 aircraft (650 were active), 37 airships, and 200 balloons, with 580 pilots and 550 observers. Naval air mobilized 11,000 men, with 4,300 for airships. The naval air section conducted 155 air attacks, 124 by aircraft and 31 by airships.

French seaplanes played a decisive role, thanks to their reconnaissance of Turkish forces advancing toward the Suez Canal. The main fleet too used seaplanes, mostly for reconnaissance. They operated in the Mediterranean in March 1916 from the converted freighter Campinas, which could operate in areas not covered by maritime aviation centers.

The Dunkirk CAM, shared with the British, operated against the Germans based in Belgium, had seaplanes for surveillance and patrol, and also operated against land-based fighters. Overseas, CAMs were located on the coast of North Africa and in early 1918 at Dakar. A center was set up in Venice by the end of May 1915. A CAM was also based at Corfu and Mytikas, Greece, in August 1917. The navy deployed a number of seaplane carriers, including Foudre in August 1914, Campinas from 1916 to 1919, Nord, Pas de Calais, and Rouen in 1916, and Dorade and Normandie in 1917.

Navy seaplanes participated in the neutralization of two German submarines, UC 38 on 14 December 1917, sunk by Lansquenet, and on 18 May 1918 U 39, obliged to seek internment in Cartagena, Spain. Maritime aviation and airships played a decisive role in antisubmarine warfare, forcing submarines to remain submerged (hence costing them their ability to observe and, especially, their mobility) and driving them away from the coast.

Summary and Assessment

By the time of the armistice of 11 November 1918, France had mobilized about 8.4 million people and suffered 1.4 million dead or missing. The navy was exhausted. It had lost 19,495 men: 11,388 dead, 607 wounded, and 7,500 prisoners.

Apart from building antisubmarine forces in the shipyards, equipment had not been renewed and was worn out by the demands of war service. Ships and men also often served far from the industrial support of metropolitan France. Prepared for a classic war fleet, sailors who completed training for work in submarines and battleships often found themselves allocated to sloops and patrol vessels. For the French sailors the war effectively continued until late 1920, due to operations against the Bolsheviks in Russia, especially within the Black Sea. The delayed demobilization led to on-board mutinies, which were quickly controlled.

In early 1922, after the return of requisitioned ships, the disposal of the oldest and most worn-out units, and the incorporation of former enemy warships (including five light cruisers), the fleet’s total tonnage in service stood at 485,000 tons, with 25,400 tons under construction and 81,600 projected. The reconstruction of the fleet began with the 1922 program.

Liaison was not always good between the different levels of responsibility. On 3 August 1914 Paris did not advise Admiral Lapeyrère that Italy had declared neutrality, which he needed to know in order to operate appropriately. The capabilities of submarines were underestimated, but fortunately the time taken by the Germans to decide on unrestricted submarine warfare in the Atlantic worked to the advantage of the allies.

The cooperation with the British, good comrades in battle, was more labored at higher levels. Responsibility in the Mediterranean, in theory left to France, was actually shared between the French, British, and Italians, each wishing to benefit from reinforcements provided by others but not wishing to lose any of their own authority within their areas or when they considered that their interests were at stake. The Mediterranean was finally divided into areas assigned to the respective navies of the three countries at a conference at Malta on 2 March 1916. The convoy system, in a case of forgetting history, was implemented much later.

If French sailors proved their courage and their capabilities, they were frequently disappointed by their often fragile, unreliable, and difficult-to-maintain equipment. It has been written that the French sailors had more problems with their equipment than they did with the enemy.

For the French overall, World War I was symbolized by trench warfare. The battles of the Marne, Verdun, and the Chemin des Dames marked every family. The evasion of the Austro-Hungarian fleet and then the entry of Italy into the war did not allow the navy its great battle in the image of Jutland. Submarine warfare, the major threat until 1917, remained virtually unknown outside of the coastal populations, as did the ultimately successful effort to oppose it.

The navy benefited from the war’s lessons, and its reconstruction starting in 1922 was difficult but successful. Unfortunately, this new navy would be virtually eliminated in difficult and unpredictable conditions during the Second World War.