![]()

BACKSTORY

Pre-1914 History

On the eve of the First World War the Russian Imperial Navy was certainly among the world’s most ridiculed armed forces. Its performance in the Russo-Japanese War—particularly the humiliating defeat at Tsushima—and the widely publicized revolt on board the Black Sea Fleet battleship Kniaz Potëmkin Tavricheskii had led both its allies and its potential enemies to assume that the Russian navy would be a negligible factor in a maritime war. Yet despite occasional blunders, its performance in two and a half years of war was on the whole competent and effective. How had this change come about in the nine years between Tsushima and Sarajevo?

From its founding by Peter the Great in 1696 until the Crimean War (1853–56) the Russian navy had performed creditably, if not always brilliantly, and had been an essential factor in Russia’s expansion in both the Baltic and Black Sea regions. By the mid-nineteenth century Russia’s structural weaknesses—underdeveloped industry, a backward social system, and a cumbersome government—were undermining the navy’s ability to defend the empire, but in the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78 the Black Sea Fleet had still managed to gain ascendancy over a nominally stronger enemy thanks to improvisation and boldness.

But between 1878 and 1904 a series of events sapped those qualities out of the navy. Starting in the 1880s the officer corps was subjected to a rigid promotion scheme, the tsenz, that focused the attention of officers on obtaining the right billets for promotion rather than on professional competence. The effects of this system were exacerbated by the navy’s dramatic expansion between 1895 and 1904, during which time the number of enlisted men rose from 26,000 to 64,400 without a corresponding increase in the number of officers. The rapid expansion of the navy under Emperor Nicholas II (r. 1894–1917) was the result of his belief that Russia’s future lay in Asia and the Pacific; by 1904 most of the navy’s battleships and cruisers were based in Port Arthur and Vladivostok, where facilities were lacking and logistical support was dependent upon the single-track Trans-Siberian Railway.

All of these factors played roles in the disastrous war with Japan. When revolutionary disturbances wracked the nation in 1905–1907, these same factors contributed to numerous naval mutinies, of which the Potëmkin’s was only the most protracted and embarrassing. The government was eventually able to muster enough loyal troops to crush the rebellions, but the situation remained tense in both society and the armed forces.

In the wake of war and revolution the navy began to address the worst of its problems. Incompetent officers were weeded out, promotions were freed from the restrictions of the tsenz, conditions on the lower deck were improved, and the creaky administrative machinery of the Naval Ministry was subjected to a number of changes. The most important of these was the founding in April 1906 of the Naval General Staff (NGS), which was intended to prevent the sort of mismatch between national policy, building programs, and base facilities that had hampered the conduct of the war with Japan.

At sea, a rigorous training program was inaugurated in the Baltic Fleet under Admiral N. O. Essen, a hero of the Russo-Japanese War; improvements in the Black Sea Fleet came more slowly, but there were advances nonetheless. The biggest problem confronting the seagoing forces was the lack of modern ships; war and revolution had undermined the empire’s economy, and recovery began only around 1910, so for several years the navy had to watch anxiously as other powers laid down dreadnought after dreadnought. The first Russian all-big-gun battleships, the Baltic Fleet’s four Sevastopol-class ships, were started only in 1909, and even then work was slow due to a lack of funds.

Reform efforts really began to pick up speed with the appointment of Admiral Ivan Konstantinovich Grigorovich to the post of naval minister in April 1911. Grigorovich was a man of great talent and energy, with clear ideas on what needed to be done to reinvigorate the navy. He was also willing to deal honestly with the new legislature, the State Duma, and soon turned its negative attitude toward the navy into a positive one. As a result, the Duma voted money for a series of warship programs: in 1911, after almost two years of uncertainty, the construction of the Sevastopol-class battleships was finally put on a firm financial basis; a program for the Black Sea (three dreadnoughts of the Imperatritsa Mariia class) was approved; in 1912 funding was granted for four huge Izmail battle cruisers for the Baltic; and in early 1914 a fourth Black Sea dreadnought (Imperator Nikolai I) was approved. These programs also included light cruisers, powerful destroyers, and submarines.

By August 1914 the Russian Imperial Navy was in the midst of a renaissance. Although most of its ships were obsolete, the shipyards were humming with new construction. The quality of its officers corps was still uneven, but the service possessed many competent—and a few brilliant—men. The technical training of crews was generally at a high level, equipment was up to date, and procedures were carefully thought out. Only two things stood in the way of Russia’s aspiration to become a great sea power: the uncertain loyalty of the navy’s enlisted men and—the most important factor of all—time.

Mission/Function

Geography compelled the Russian navy to maintain several separate forces—the Baltic and Black Sea Fleets and the Siberian, Caspian, and Amur River Flotillas. The two fleets were by far the largest and most important formations, but both were isolated in enclosed seas. Moreover, the only access to the Black Sea, the Turkish Straits—the Dardanelles and the Bosporus—were closed in peacetime by international treaty to all warships except those of Turkey; thus the Baltic and Black Sea fleets could never operate together. Although naval officers trained together and were transferred from one sea to the other, the two fleets faced completely different conditions and developed independent traditions and a certain degree of rivalry.

In terms of Russian naval war planning, there were two basic assumptions: first, that the war on land would be the dominant factor in determining victory or defeat; second, that a future war would be short. These assumptions were especially important in the Baltic, where the navy’s main task was to prevent the Germans from launching maritime attacks on St. Petersburg (renamed Petrograd in September 1914). The navy was also charged with preventing German landings that could outflank the army’s land defenses. The Russian territory of Finland was seen as especially vulnerable, since a German landing there might trigger a revolt among a population unhappy with Russian rule.

The Baltic Fleet’s 1912 war plan, which was put into effect in August 1914, had been developed by the NGS in cooperation with the Baltic Fleet staff. Its central feature was a dense minefield, dubbed the “Central Position,” barring entrance to the Gulf of Finland. A cruiser patrol line to its west would warn of the approaching enemy. When that warning came, destroyer flotillas based on the flanks of the central position would come out to launch massed torpedo attacks; their primary targets would be troop transports (if the enemy planned a landing) and capital ships. Once these attacks had been carried out, the destroyers and cruisers would fall back to the east of the central position, where all forces would concentrate for the defense of that position. At best, this system would prevent an incursion by the far stronger German fleet into the Gulf of Finland; at worst, it would hold off the enemy for at least fourteen days, which would give the army time to mobilize to defend against a German amphibious assault.

In the Black Sea, developing a war plan proved more difficult—the NGS was in favor of an aggressive campaign to blockade the Bosporus, while the fleet staff was more cautious and tended to focus on defending Russia’s coasts. The upshot was that when the Turco-German fleet attacked on 29 October 1914 the fleet went to war without a plan, which led to some confusion in the initial operations.

In the Pacific, Russia had come to terms with Japan, whose naval power she could no longer hope to match. A 1907 treaty sorted out spheres of influence in Manchuria, trade, fishing rights, and the other desiderata left over from the war. Russia’s naval force in the Far East, the Siberian Flotilla, could therefore be limited to a pair of cruisers and a few obsolete destroyers and submarines. Many of these vessels would be recalled to European waters after the war began. The Caspian and Amur River Flotillas were minor forces, intended primarily for police and border-protection functions. As for the north, it was completely ignored in naval plans—a corollary to the short-war assumption, which did not envision the massive imports of arms and material that a long war would require.

ORGANIZATION

Command Structure

Administration

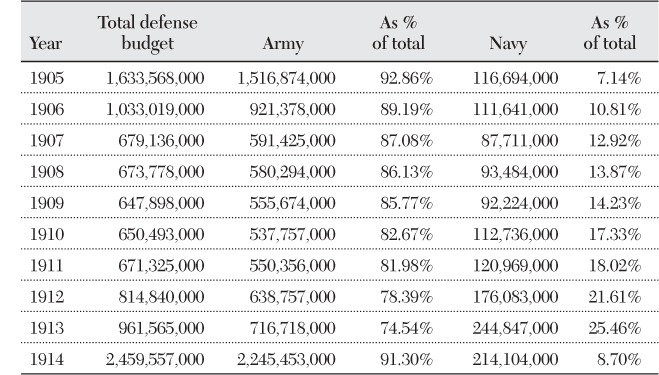

The Naval Ministry was housed in the Admiralty (Admiralteistvo) in St. Petersburg. The naval minister was always a serving admiral; he, like all other ministers, was appointed by, and responsible solely to, the emperor. By far the most outstanding of the naval ministers in this era was I. K. Grigorovich, who held the post from April 1911 to February 1917. During his period in office the naval administration was streamlined, with overlapping departmental functions eliminated by regulations that clearly spelled out the authority of the various branches. Grigorovich also managed to repair the navy’s frayed relations with the State Duma while simultaneously retaining the emperor’s trust—not an easy tightrope to walk. As a result of his efforts the naval budget increased dramatically in the last few years before the war, as shown in table 6.1.

Table 6.1 Russian Army and Navy Expenditures, 1905–14 (in rubles)

Notes: The exchange rate at the time was $1.00 = 1.94 rubles, or £1 = 9.46 rubles.

The navy’s expenditures for 1910 included 16,851,000 rubles for paying down the ministry’s outstanding debts.

Source: L. G. Beskrovnyi, Armiia i flot Rossii v nachale XX v.: Ocherki voennoekonomicheskogo potentsiala (Moscow: Nauka, 1986), 226, 227, 229.

Although the minister had broad powers over the naval administration in peacetime, a number of key appointments in the navy were made directly by the emperor and so were outside the minister’s control. This opened the door to court politics and intrigue. Among the officers appointed by the emperor were the fleet commanders and some of the major department heads. One of these imperial appointees was the head of the Naval General Staff, which was charged with defining Russia’s naval requirements in the various theaters, determining strategies to meet those needs, and formulating the programs to make those strategies work, in terms of both shipbuilding policy and shore facilities. Initially the NGS was small—fifteen officers—and it received little support from the naval ministers. This placed it in a weak position within the ministry’s bureaucracy, but under Grigorovich it gained considerable power.

During the war some administrative changes were introduced. The most important came in 1915 with the creation of two assistant ministers, one for combatant affairs and the other for technical and financial matters. The first assistant, who was in charge of the ministry in Grigorovich’s absence, was Vice Admiral A. I. Rusin, who was simultaneously the chief of the Naval General Staff; the technical/financial assistant minister was Vice Admiral P. P. Muravev.

After the February Revolution of 1917 the administration of the navy was subjected to numerous changes, and lines of responsibility became blurred. In the event, none of these changes had much influence on the conduct of the war, since after the February Revolution the power of the central authorities was increasingly tenuous.

Organization

Command Organization

The emperor was the commander in chief of the armed forces, although in 1914 he appointed his soldierly uncle, the Grand Duke Nikolai Nikolaevich, as supreme commander. The high command—Stavka, in Russian—was established at Baranovichi in Poland. Following the army’s great defeats in the summer of 1915, Stavka was relocated eastward to Mogilev, and Nicholas II assumed the title of supreme commander. The actual running of the war was entrusted to the emperor’s chief of staff, General M. V. Alekseev.

Once war began, the Naval Ministry became a purely administrative organ—as Naval Minister Grigorovich often remarked, “The fleet requires—we fulfill.”1 Belying its name, the Naval General Staff did not assume direct command functions over the major fleets, a task for which it was neither intended nor equipped. Instead, the Black Sea Operations Section of the NGS, headed by Rear Admiral D. V. Neniukov, was transferred to Stavka, to which the Black Sea Fleet was directly subordinated. The Baltic Fleet, on the other hand, was subordinated to the VI Army, charged with the defense of St. Petersburg, and the Baltic Operations Section of the NGS was incorporated into VI Army headquarters.

The naval administrations at Stavka and VI Army headquarters were small organizations that could do little more than pass reports upward and directives downward, while the higher authorities were generally too preoccupied with the land fronts to interfere with the operations of the fleets. This somewhat vague framework gave the fleet commanders a considerable, perhaps excessive, degree of independence. For example, Stavka’s naval administration was constantly frustrated by the Black Sea Fleet’s failure to respond to its directives. On the other hand, the Baltic Fleet bridled under the cautious policies of VI Army command, although it obeyed them nonetheless.

Admiral Grigorovich considered these arrangements unsatisfactory, and after the emperor assumed command at Stavka he began pressing for a reorganization. The eventual result of this pressure was the establishment in January 1916 of an Imperial Naval Field Staff within Stavka; the chief of the Naval General Staff, Vice Admiral A. I. Rusin, became chief of the Naval Staff. In practice, however, these changes had little effect on the conduct of the war.

Fleet Organization and Order of Battle

The Russian navy’s major combatant formations were the Baltic and Black Sea Fleets, commanded in August 1914 by Admirals N. O. Essen and A. A. Ebergard, respectively. Upon the outbreak of war, the fleet commanders automatically assumed authority over the ports and other naval facilities in their theaters.

For battleships and cruisers, the fundamental unit was the brigade (brigada) of four ships, while for destroyers it was the flotilla (divizion) of nine ships; two flotillas formed a brigade, two brigades a division (diviziia). For submarines the basic unit was the section (otdelenie), consisting of two large or three small boats; two to four sections would make a flotilla, and two flotillas would make up a brigade. A detachment (otriad) was a separate formation of ships; these might be temporary, as for a special purpose, or more permanent, such as the Artillery Training and Torpedo Training detachments.

Although the division-brigade-flotilla structure remained in place throughout the war, in 1915 new tactical formations were introduced. The fleets were divided into a number of “maneuvering groups.” In the Baltic, each of these consisted of two battleships, a cruiser, and a number of destroyers; if the Germans attempted to penetrate the defensive mine barrier at the entrance to the Gulf of Finland, the groups would maneuver independently in protecting the minefields. In the Black Sea, the maneuvering groups consisted either of a single dreadnought or several predreadnoughts, the idea being that each group should by itself be more powerful than the Turco-German battle cruiser Goeben, so that each could operate independently without fear of being overwhelmed by the faster German ship.

Communications

Tactical

Like other navies, the Russian navy used flag signals and signal lamps for maneuvering at sea; maneuvers could also be conducted by low-power radio. Before the war a great deal of attention was devoted to circumventing enemy jamming by coordinated frequency changes; this was considered especially important given the defensive system of the Baltic war plans, in which scouting forces would have to alert the fleet to the enemy’s approach by radio in time to effect a concentration.

As for codes and ciphers, until 1916 Russian communications used, in the words of one officer, “naïve” ciphers; he went on to say that “the entire difference between the Germans and ourselves was the fact that we transmitted little, while they were garrulous.”2 New ciphers, employing super-encryption, were finally issued in the summer of 1916. As for codes, there were different ones for large ships, light forces, submarines, and auxiliary vessels. Thus if a submarine was lost, only that code had to be replaced. Messages were not to be repeated in different codes; instead, large surface ships had copies of all the other codes, so that they could both send and receive messages from the smaller units operating with them without having the same messages broadcast in different codes, which would have provided any German code breakers with a point of entry into the codes.

Strategic

Most strategic communication was conducted via cables running over Russian territory or under waters controlled by Russia. This provided a secure means of communication between Stavka, the Naval Ministry in St. Petersburg, the Baltic Fleet base in Helsingfors (modern Helsinki), and the Black Sea Fleet command in Sevastopol, as well as the various outlying forces. The Hughes Teletype system was much used; although somewhat slow, it provided for secure strategic communications throughout the war. For communicating with ships at sea, the main fleet bases at Helsingfors and Sevastopol were equipped with powerful (thirty-five-kilowatt) radio stations.

Intelligence

The Third Branch of the Naval General Staff was responsible for intelligence; naval attachés, who reported directly to it, were encouraged to develop espionage networks. They obtained some successes. In the Baltic a number of agents were infiltrated into German territory and observation posts were set up in the eastern Danish islands to report on the movements of German warships in the vicinity of Kiel. Matters proved to be more difficult in Turkey; although the Russian navy established espionage rings in Constantinople, they were often short-lived, and the timely transmission of information remained problematic.

But the Russian navy’s main source of intelligence was the decryption of German naval radio messages, thanks to the codebook and other materials captured after the cruiser Magdeburg ran aground in Russian territory on 26 August 1914. The Russians initially did not establish a centralized code-breaking office to exploit the material; instead, decryption was carried out by both the Intelligence Section of the Baltic Fleet’s staff and the Service of Observation and Communications (Sluzhba nabliudeniia i sviazi, or SNIS), under Captain 1st Rank A. I. Nepenin. Eventually, however, the SNIS took over most of the decryption work, which was carried out by a specially assembled staff at the Shpitgamn radio station, in Estonia. SNIS prepared daily summaries of the situation, based on radio decrypts and radio direction finding (by 1915 the SNIS was operating a network of D/F stations). The fleet staff, in turn, prepared weekly summaries based on the SNIS materials, as well as agent reports and other sources. During the war it was standard practice for ships going out on missions—including the British submarines operating in the Baltic—to get briefings on the current situation at SNIS headquarters in Revel (modern Tallinn, Estonia).

Little information is available regarding code breaking in the Black Sea; however, as the Naval General Staff reported to the British Room 40, “We know all ciphers in Black Sea except for the 3-letter-groups W/T [wireless] messages.”3 Overall, however, the published literature suggests that the Black Sea Fleet’s radio intelligence was not as well organized as that of the Baltic Fleet.

Infrastructure, Logistics, and Commerce

Bases

Kronshtadt, located about fifteen nautical miles west of St. Petersburg on Kotlin Island, had long served as the Baltic Fleet’s main base. The fleet’s major schools and depots were located there, as were ship-repair facilities. Its greatest disadvantage was that it was usually icebound from around the end of December until April, so any ships based there were immobilized for about four months. In 1912 the NGS decided that Revel would make a better base, since icebreakers could keep it open year-round, and a vast program of harbor expansion and improvement was undertaken. This work was far from complete in August 1914, and therefore Revel was used only by destroyers and submarines, while the big ships were based at Helsingfors, which was generally frozen from late January to mid-April. During the war, forward bases were established in the Åland Islands and in the Gulf of Riga.

In the Black Sea the main base was Sevastopol, a deep inlet on the western coast of the Crimean Peninsula. During the war Batumi was used as a support base for units operating in the Caucasus and along the northern coast of Anatolia, but facilities there were minimal.

In the Russian north the few facilities available originally belonged to the Ministry of Trade and Industry but were transferred to the navy after the outbreak of war. The main bases were the ancient port of Arkhangelsk on the White Sea and the ice-free port of Romanov-na-Murmane (now Murmansk), which was developed during the war. (See map 6.1.)

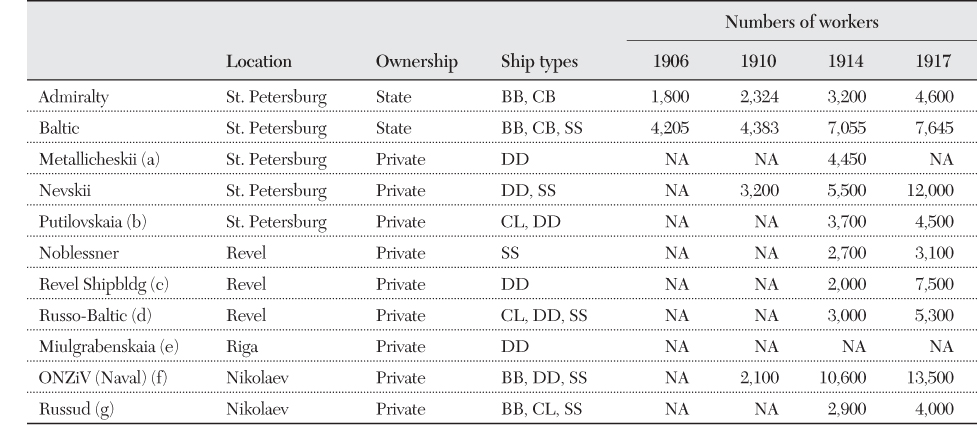

Industry

Russia’s state shipyards were known for their slow pace of construction and their corruption. These faults became all too obvious after the Russo-Japanese War, when it was revealed that naval shipbuilding was in essence a gigantic Ponzi scheme, under which the cost overruns of incomplete ships were being paid for by credits allocated to new ships. Thus in the wake of the war, when new shipbuilding funds dried up, all work, even on ships well advanced, slowed to a crawl due to lack of money. This situation persisted until 1911, when the Duma granted 16.85 million rubles to pay off the Naval Ministry’s debts. Once he was appointed naval minister, Admiral Grigorovich was able to replace ineffective managers and reorganize several of the institutions involved in shipbuilding. As a result, the state facilities were soon operating at a much increased tempo.

Grigorovich also sought to encourage private industries, recognizing that thanks to a massive influx of foreign investment eager to win profits from Russia’s naval reconstruction, these firms had enormous capital to work with. Foreign concerns either partnered with existing Russian firms or founded completely new shipyards. In addition to financial backing, the foreign firms provided sorely needed technical expertise; although Russia had a cadre of excellent naval constructors and engineers, there were too few of them to support the navy’s burgeoning needs.

Table 6.2 Ships Added to the Baltic Fleet, 1914–18

* Includes six submarines authorized for the Siberian Flotilla; these were still under construction in the Baltic when war broke out and were therefore added to the Baltic Fleet. Also included are twelve boats of the 1915 program that were never begun and five boats ordered from the United States in 1915 and delivered in sections by railway from Vladivostok.

Table 6.3 Ships Added to the Black Sea Fleet, 1914–18

* Includes 8 boats of the 1915 program that were never started, as well as six Holland boats ordered from the United States in 1916–17 and delivered in sections by railway from Vladivostok.

Nevertheless, the industrial underpinnings of Russia’s shipbuilding industry remained weak, and enormous quantities of machinery and equipment had to be ordered from foreign firms—many of them German. Ultimately, the problem was that Russia lacked the means to create new industries; machine tools, hydraulic presses, fine instruments—all had to be ordered abroad. Thus Russian wartime submarine construction was severely constrained by the lack of domestically produced diesel engines (engines for some boats had to be taken from the gunboats of the Amur River Flotilla); turbines had to be ordered in Britain for the Black Sea dreadnoughts; and the spherical bearings used to support the 14-inch turrets of the Izmail-class battle cruisers, ordered in Germany, were never delivered, and replacements proved impossible to find. (See tables 6.2, 6.3, and 6.4.)

Shipping

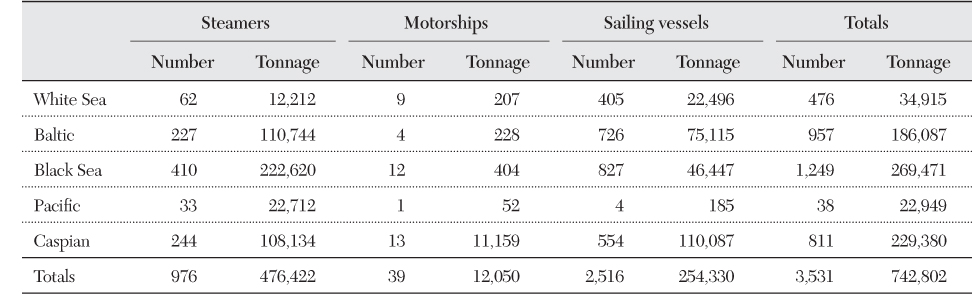

Russia’s merchant marine was miniscule—less than 6 percent that of Great Britain. However, this does not mean that Russia’s volume of trade was small, just that it was carried in foreign bottoms. In fact, Russia’s trade was growing as the empire rapidly industrialized, and the imports of manufactured goods that flowed into the empire through the Baltic were paid for by the export of Black Sea grain. This explains the interest of both the Naval Ministry and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in keeping the Turkish Straits open to Russian trade, as well as the fact that one of Russia’s most important wartime political goals was control over these straits.

During the war the navy commandeered many merchant ships, both Russian and foreign, trapped in the Baltic and Black Sea. Hundreds of vessels, from fishing trawlers to large steamers, were pressed into naval service and made vital contributions to Russia’s naval war. (See table 6.5.)

Personnel

Demographics

The Russo-Japanese War had a profound effect on the naval officer corps. The most useless officers were weeded out, and the number of admirals was reduced through retirement. Nevertheless, there remained too many officers of indifferent quality. Although reforms opened the officer corps to “Persons of all classes, of the Christian religion” possessing a higher education, it remained a largely aristocratic body—93 percent of entrants to the Naval Corps between 1910 and 1915 were from gentry families.

Russia was a multinational empire, and the officer corps reflected this fact. Although the majority of officers were Russians (a term also used for Ukrainians—“Little Russians”—and White Russians), there were also ethnic Swedes from Finland, Poles, and many others. The largest non-Russian group—about 20 percent—were ethnic Germans (ostzeiskie) from the southern Baltic coast, often referred to as the “Baltic barons.” There seems to have been little if any discrimination against non-Russian officers; for example, there were navy-sponsored churches for Catholics and Lutherans at Kronshtadt, and at the outbreak of war the Baltic Fleet was commanded by an ethnic German and the Black Sea Fleet by an ethnic Swede. In 1914 there were 4,123 officers serving in all branches; by early 1917 this number had grown to 6,089, including 173 admirals and generals. (See table 6.6.)

Table 6.4 Major Shipyards Engaged in Warship Construction, 1906–17

a. Supported by A.G. Vulcan (Hamburg).

b. Supported by Blohm & Voss.

c. Supported by Normand and Schichau.

d. Supported by Schneider-Creusot.

e. Supported by Schichau.

f. French financial backing, technical support from Vickers.

g. Technical assistance from John Brown.

Sources: Beskrovnyi, Armiia i flot Rossii v nachale XX V., 198–99; Istoriia otechestvennogo sudostroeniia, vol. 3, 175–215.

Table 6.5 The Russian Mercantile Marine as of 1 January 1914

Source: Stateman’s Year-Book, 1915, 1299.

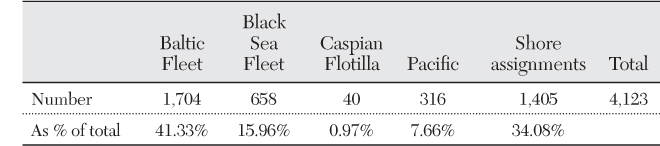

Table 6.6 Number of Officers, by Assignments, 1914

There was less ethnic diversity among the enlisted personnel; this was in part a result of the conscription laws, which exempted not only individuals for various reasons but also entire regions of the empire—for example, Finland was excluded from conscription, thus depriving the navy of a potential source of seafaring men. But the navy also sought to ensure a majority of Russians (again including Ukrainians and White Russians) in every ship or unit; Jews and national minorities from the empire’s borderlands were deliberately excluded. The Baltic Fleet generally received conscripts from northwestern Russia and the provinces bordering on the Baltic, whereas the Black Sea Fleet’s crews generally came from the nine provinces bordering that sea. As a result, the majority of the men of the Baltic Fleet (75–80 percent) were Russians, while in the Black Sea Ukrainians predominated (circa 65 percent).

For obvious reasons, the navy wanted conscripts with some experience of the sea or boat handling, or men who were familiar with machinery. The latter tended to be workers from the urban areas, who were generally better educated than the rural peasants, who still made up the bulk of the army (the literacy rate in the navy was better than 80 percent, while in the infantry it hovered around 50 percent). This conscription policy had a major drawback—urban workers usually had been exposed to some form of socialist propaganda or had even participated in revolutionary activities.

The navy was unpopular with conscripts, primarily because the peacetime term of service was five years, compared to only three years in the army. The draftees were inducted in October and trained ashore until March. At this point the bulk of the men would be distributed to their posts, on board ship or ashore, while the brighter men would be selected for additional training as petty officers. The reenlistment rate of petty officers was very low, which meant that they usually had less shipboard experience than the men they led. As a result, petty officers identified with the enlisted men, not with the service. Warrant officers—konduktory—were specialist enlisted men who had decided to remain in the navy. Their small numbers (about 1.6 percent of the crews) and the fact that they were much disliked by the enlisted men meant that they could hardly form a bridge between the officers and the lower deck. After the February Revolution in 1917 there were proposals to eliminate them altogether, and this had in fact been done by December 1917.

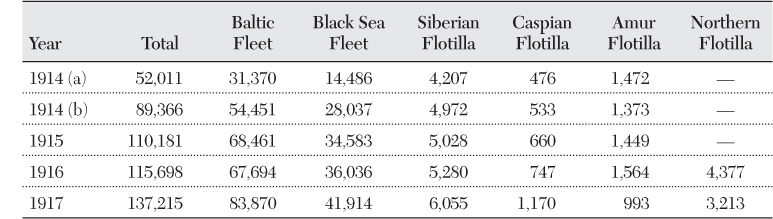

The navy’s personnel strength peaked in early 1917, when there were more than 137,000 enlisted men on the books. After the February Revolution it declined sharply, and by 1 June 1918 the number had plummeted to 48,216, due to a combination of desertions and the siphoning off of sailors to the land fronts of the accelerating civil war. (See table 6.7.)

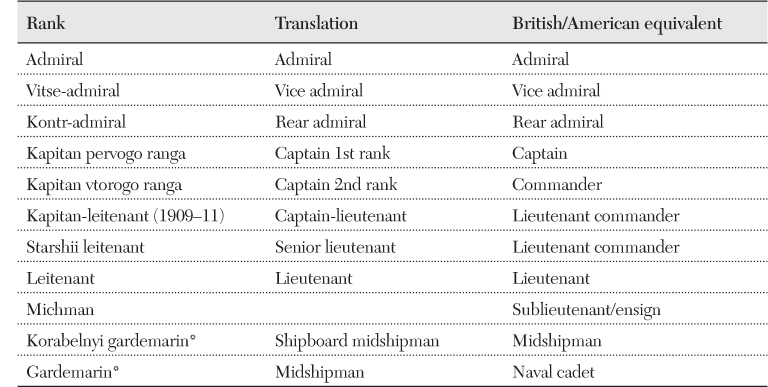

Training

Most line officers entered the navy through the Naval Cadet Corps (renamed the Naval Corps in 1906). After the war with Japan the educational emphasis shifted from general and theoretical subjects to naval professional topics (especially naval strategy and tactics). Another postwar change was an increase in the total number of cadets, from 600 to 750, in an effort to replace wartime losses.

The Naval Corps accepted applicants between the ages of fourteen to sixteen; for the first three years of its six-year program a cadet was rated as a gardemarin (midshipman) and in addition to classroom studies would go on summer cruises. After passing an examination, he would be promoted to korabelnyi gardemarin (shipboard midshipman) and embark on a long cruise, usually to the Mediterranean; upon completion of this and passing another examination, he would be promoted to michman (ensign, or sublieutenant).

The Nicholas Naval Academy was the equivalent of a war college, offering a two-year program in the study of naval strategy, tactics, and other advanced topics. The top graduates would be selected for a third year of study, intended to train officers for the Naval General Staff.

Compared to the army, wartime attrition of naval personnel was low, but the numerous auxiliary vessels taken over from commercial service dramatically increased the number of officers and men required. After the outbreak of war the senior classes of midshipmen were given early promotions to michmany, which provided an additional 259 officers. In 1916 a special three-month class was established for volunteers, who were intended strictly for duties ashore, thereby liberating other officers for service afloat. The classes were organized at Oranienbaum, near Petrograd. Candidates had to have high school educations and be less than twenty years old. The first group of 150 men was graduated in the late summer of 1916. (See table 6.8.)

Table 6.7 Sailors in Service, All Fleets and Flotillas (not including officers)

a. Premobilization figure.

b. Postmobilization figure.

Note: The figures for 1914 do not include konduktory.

Source: Beskrovnyi, Armiia i flot Rossii v nachale XX v., 211.

Rank |

Translation |

British/American equivalent |

Admiral |

Admiral |

Admiral |

Vitse-admiral |

Vice admiral |

Vice admiral |

Kontr-admiral |

Rear admiral |

Rear admiral |

Kapitan pervogo ranga |

Captain 1st rank |

Captain |

Kapitan vtorogo ranga |

Captain 2nd rank |

Commander |

Kapitan-leitenant (1909–11) |

Captain-lieutenant |

Lieutenant commander |

Starshii leitenant |

Senior lieutenant |

Lieutenant commander |

Leitenant |

Lieutenant |

Lieutenant |

Michman |

|

Sublieutenant/ensign |

Korabelnyi gardemarin* |

Shipboard midshipman |

Midshipman |

Gardemarin* |

Midshipman |

Naval cadet |

* From the French term garde de marine.

Relations between officers and enlisted men were notoriously poor; discipline was frequently harsh, and although striking subordinates was illegal, it was not unknown. Enlisted men were not allowed in certain parks; they could not smoke in the street or ride on the inside of trolleys. They had to address junior officers as Vashe Blagorodie (Your Honor) and senior officers as Vashe Vysokoblagorodie (Your High Honor), while officers used the familiar “thou” (ty) in addressing enlisted men—the same form of address used for children.

But these grievances should not be overemphasized. Relations between Russia’s social elites on the one hand and the rural peasantry and urban proletariat on the other were poor to start with; naval service and wartime conditions merely exacerbated this schism. Against this background, the inactivity of much of the fleet, combined with the growing influence of revolutionary propaganda, made for an explosive situation. Also, paradoxically, strict discipline was often combined with lax oversight, which made it easier for revolutionary parties to infiltrate naval bases and, on occasion, to organize large gatherings. One result of this became evident in 1912 when a plot for a fleetwide revolt in the Black Sea was exposed and several sailors were executed.

The lax supervision exercised by officers probably owed a good deal to a phenomenon noted by one volunteer officer, Konstantin Benkendorf. Having served in the Russo-Japanese War, he was recalled to duty in August 1914 and noted that a change had come over officer-enlisted relations between the wars: “I felt that both sides, officers and men, had withdrawn from each other and, what is more, this fact was not only accepted, especially by the younger officers, but even fostered among them.”4 Perhaps Benkendorf’s lapse in service allowed him to see something missed by others—that the officers were as estranged from the men as much as the men were from their officers. It was perhaps something that was easier to ignore than address, and many officers probably felt more comfortable immersing themselves in professional matters than trying to grapple with issues fraught with enormous social implications for both the navy and the empire. Whatever its root causes, the rift between officers and men would have terrible consequences when revolution broke out in early 1917.

Surface Warfare

Doctrine

In a fleet action, the Russian navy intended to fight at long ranges—in 1912 the Baltic Fleet was conducting gunnery practice at an average range of 12,400 yards for big guns, and by 1914 the Black Sea Fleet staff expected to engage at ranges of 16,000–20,000 yards. A form of divisional tactics would be employed, in which the individual brigades would maneuver independently while adhering to an overall battle plan; this would allow each brigade to make full use of its advantages in action, without being hindered by slower or weaker ships. The primary function of destroyers, in either a fleet action or defense of a mine barrier, would be to launch salvos of torpedoes at the enemy—hence the extraordinarily heavy torpedo batteries of the Novik-type destroyers.

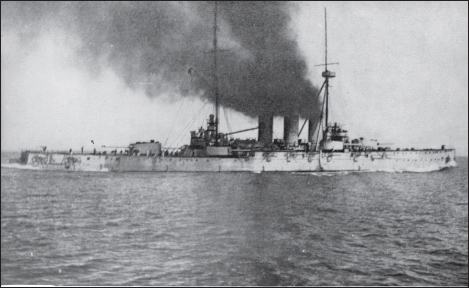

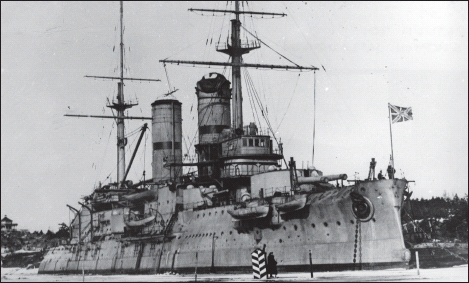

Ships/Weapons

In August 1914 the only modern surface combatant in the Russian navy was the destroyer Novik, and for the war’s first year it was the older ships, the survivors of the Russo-Japanese War and the ones built in its immediate aftermath, that would bear the brunt of the fighting at sea. Predreadnought battleships formed the core of the Baltic and Black Sea Fleets. In the Baltic, the most powerful units were the Andrei Pervozvannyi and Imperator Pavel I, which had entered service in 1911 after eight years under construction. Their design had been much altered as a result of the experience of the Russo-Japanese War; their hulls had been armored overall against high-explosive shells, 120-mm guns had replaced the 75-mm antidestroyer guns of the original design, their superstructures had been much reduced, and cage masts had been fitted. They were effective, if outdated, units.

The other predreadnoughts in both the Baltic (two ships) and Black Sea (five ships) had been refitted to one degree or another before the war. Their superstructures had been cut down, turret machinery improved to increase the rate of fire, gun elevations increased, and modern range finders and sights fitted. None were of outstanding design, but they would give good service during the war.

The four Baltic dreadnoughts of the Sevastopol class were rushed into service in late 1914, although they were not ready for combat until the summer of 1915. They featured a powerful armament of twelve 12-inch guns and could make twenty-four knots, but they were relatively weakly protected with a 9-inch belt. Their Black Sea cousins of the Imperatritsa Mariia class featured the same armament but a slower (twenty-one-knot) speed and 10.3-inch belts; three of these ships entered service during the war. A fourth ship, Imperator Nikolai I, was larger and more stoutly protected, but she was never completed. All Russian dreadnoughts shared a dangerously weak underwater protection scheme that lacked a protective bulkhead; this was a deliberate choice made in order to devote the maximum possible weight to offensive features. The Baltic dreadnoughts saw little action, but the Black Sea ships had several brief encounters with the enemy.

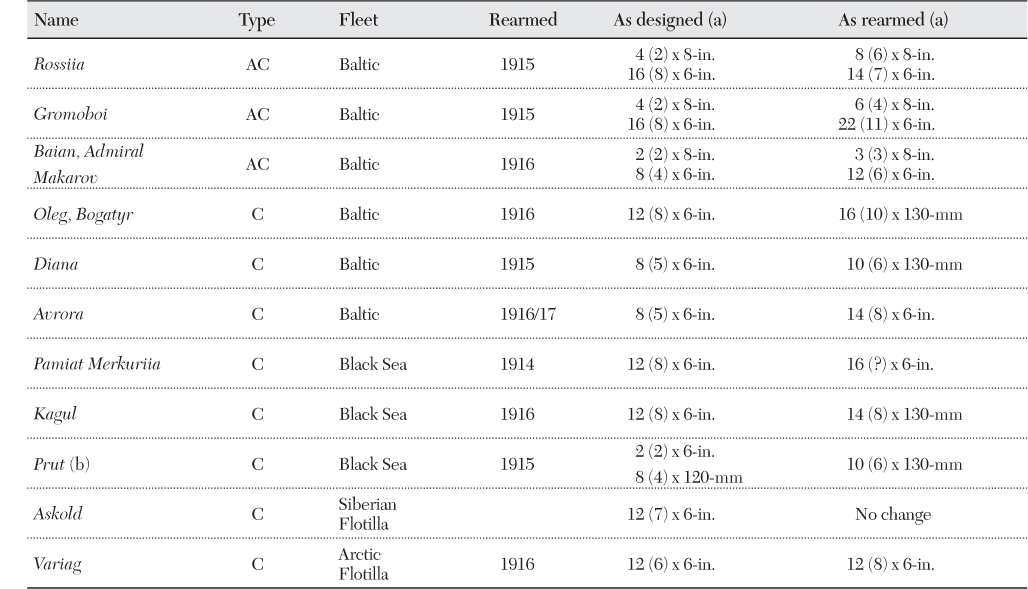

As for cruisers, none of the turbine-driven ships laid down in 1913–14 were destined to be completed by the imperial navy. Of the older ships, by far the most impressive was the Vickers-built Riurik, a handsome ship that to all intents and purposes was the equivalent of a predreadnought battle cruiser. She frequently served as Admiral Essen’s flagship. All the other cruisers were of pre-1905 design, and all of them underwent extensive rearming either shortly before or during the First World War, as shown in table 6.9.

Table 6.9 Rearming of Cruisers, 1914–17

Note: Pallada of the Baltic Fleet and Zhemchug of the Siberian Flotilla were sunk before they could be rearmed.

(a) Figures in parentheses indicate the number of guns that could train on one broadside.

(b) Ex-Turkish Mecidiye; struck a mine and sank in shallow water off Odessa on 3 April 1915 and subsequently raised by the Russians.

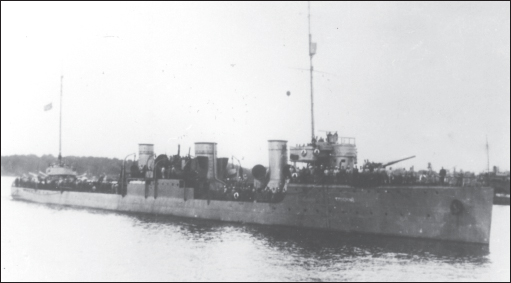

In terms of destroyers, the Baltic Fleet was much indebted to the “Special Commission for Strengthening the Fleet by Voluntary Contributions,” which funded the construction of eighteen destroyers in 1904–1906. Built by both foreign and Russian shipyards, all these ships were essentially similar: 570–640 tons, twenty-five to twenty-six knots, armed with a pair of 75-mm guns and two or three 18-inch torpedo tubes (prior to the war, the 75-mm guns were replaced by 4-inch guns). Destroyers of similar armament but of smaller size were built by government funds, with the result that by 1914 the Baltic Fleet had a relatively uniform force of thirty-nine. The Black Sea Fleet had thirteen similar ships, and in both fleets there were considerable numbers of older and smaller units.

The prototype of the new generation of destroyers was the German-designed Novik; she formed the basis for seven subsequent classes, built to varying designs by different shipyards. Thirty of these fine ships were completed during the war, seventeen for the Baltic and thirteen for the Black Sea. Fast and well armed, these ships were among the best destroyers in the world; their worst fault noted in service was that some of the Black Sea hulls suffered from poor stability, which meant that they had to retain a certain amount of oil fuel as ballast, reducing their range.

A considerable number of older torpedo boats remained in service; some were used as dispatch vessels, some were converted to minesweepers. Also deserving mention were the gunboats, a type much favored by the Russian navy (seven in the Baltic, three in the Black Sea). Most were of older construction, but all gave good service by giving fire support to troops ashore. Numerous auxiliaries were acquired or built during the war, ranging from large vessels used as seaplane carriers to small motor minesweepers and antisubmarine launches.

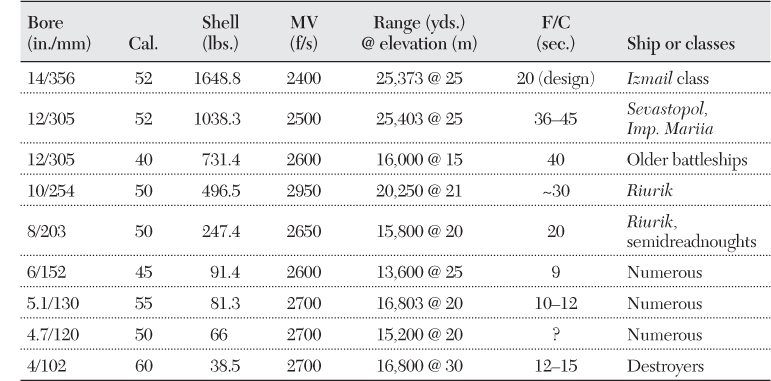

As for the guns arming Russia’s surface ships, they generally proved very effective, thanks to a thorough overhaul of shipboard gunnery carried out after the war with Japan. Rate of fire was increased, and shells were much improved; heavy shells with TNT as the bursting charge were introduced in 1908, and by 1914 Russian armor-piercing shells may have been the best in the world. Postwar British tests showed that in terms of penetrative power at oblique angles (twenty degrees) Russian 12-inch shells were only slightly inferior to the British post-Jutland Greenboy shells.

Fire control was explored in experiments conducted by the Black Sea Fleet after the war with Japan. Gunnery doctrine called for frequent and dense salvos—hence the demand for exceptionally high rates of fire in new gunnery systems and the twelve-gun broadsides of all dreadnought designs. The 1911 Geisler fire-control system included a range clock and a device to correct for the effects of bore erosion. Immediately before the war five of Arthur Pollen’s Argo clocks were purchased; four of these, delivered after the start of the war, were installed on the Sevastopol-class dreadnoughts. Ships were equipped with a variety of range finders, all of long baseline—five-meter Zeiss instruments were in the dreadnoughts as completed.

Table 6.10 Major Russian Guns, 1914–17

Note: Russian practice measured caliber length from the muzzle to the rear face of the breech end (excluding the breech block and its fixtures).

Source: Aleksandr Shirokad, Entsiklopediia otechestvennoi artillerii (Minsk: Kharvest, 2000).

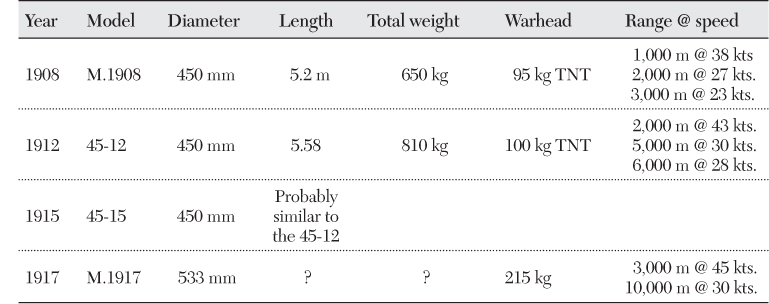

Source: Iu.L. Korshunov and G.V. Uspenskii, Torpedy rossiiskogo flota (Morskoe oruzhie 1; St. Petersburg: Gangut/Neptun, 1993), 26–27.

A unique feature of Russian gunnery was a highly developed system for concentration of fire. Three ships would be linked by special shortwave radio sets; the middle ship would take on the role of the “master” ship, relaying fire-control data to her consorts, who would make corrections based on their positions relative to the master. Although in action the Russian system seems to have been overly complex and subject to error, it foreshadowed methods adopted by the Royal Navy after Jutland. (See table 6.10.)

Russian guns were of excellent quality, but Russian torpedoes displayed a number of persistent problems, including erratic running, failure to detonate, and most disturbing of all, circling. Such problems were by no means unique to Russia, however. By 1914 the principle suppliers of torpedoes were the Obukhovskii and Lessner Works, although Whitehead’s Fiume Works continued to provide limited numbers as well as designs. The Model 1908 torpedo introduced both a TNT warhead (instead of wet guncotton) and dry-heater propulsion. The Model 45-12 torpedo was the first to employ wet-heater propulsion; just before the war 250 of these were ordered from Fiume, but only twenty-four had been delivered by August 1914. As a result, the Model 45-15, a Russian-made variant of the 45-12, was designed.

All these torpedoes were 450-mm (nominally 18-inch) in diameter. The Russian navy began development of a 533-mm (21-inch) torpedo only in 1917. Prototypes were ordered from the Lessner Works, but none were ever delivered.

In addition to conventional torpedo tubes, the Russian navy developed the Dzhevetskii gear, a trainable, externally mounted launcher for submarines (also adopted in French submarines). Also unusual were the M.1913 triple tube mountings of the post-Novik destroyers. These were designed by the Putilovskii Works and allowed the two outer tubes to be trained up to seven degrees separately from the central tube, thus facilitating the launching of spreads. (See table 6.11.)

Submarine Warfare

Offensive

Doctrine

Initially, submarines were regarded as a harbor defense weapon, but after the Russo-Japanese War the need was seen for larger boats that could attack the enemy at sea. As in most other navies, however, no thought was given to using submarines as commerce raiders. There was also some interest in “fleet” submarines, capable of operating tactically with the surface fleet, but the large boats ordered under the 1915 program to meet this requirement were never laid down.

Boats/Weapons

By 1914 the Russian navy had collected a submarine force that was impressive in numerical terms but possessed little combat value. Many of the boats had been hurriedly acquired during or after the Russo-Japanese War; most were small, and all were obsolete by 1914. Nevertheless, early in the war several of these craft were brought by railroad from Vladivostok in the Far East to serve in the European theaters.

For the first year of the war, all the effective boats in service were in the Baltic Fleet—four Kaiman-class (1905–11, 409 tons on the surface, 482 tons submerged), based on the designs of the American inventor Simon Lake, and the Akula (1906–11, 370/475 tons), designed by the Russian naval constructor I. G. Bubnov. The Black Sea Fleet did not have a single useful submarine. However, there were no less than eighteen boats under construction in Baltic shipyards, and another six were building for the Black Sea Fleet in August 1914. Despite the fact that these submarines had been laid down under the programs of 1911 and 1912, not one of them would be ready for service before 1915.

The majority of submarines under construction were designed by Bubnov, who had the support of the Naval Technical Committee. Taking his Akula as a prototype, he designed the three Nerpa boats for the Black Sea Fleet (1911–15, 630/773 tons) and the eighteen of the Bars class (1913–17, 650/780 tons) for the Baltic Fleet. Their long building times probably played a role in the persistent flaws that plagued his designs. Their hull forms were poor, which reduced their speed; diving times were slow, on the order of three minutes, although at the time this was by no means unique to Bubnov’s boats. They also tended to produce thirty-foot “fountains” while diving as the main ballast tanks flooded, often revealing their presence just as they were getting ready to attack.

Other problems were not Bubnov’s fault. Among these was the weakness of Russia’s diesel-engine industry. This led to many engines being ordered from German firms, leaving most of the Nerpa- and Bars-class boats without engines once war began. Some engines were taken from the new gunboats of the Amur River Flotilla, and others were ordered from the New London Ship & Engine Company of Groton, Connecticut, but these were far less powerful than the intended units, greatly reducing the surface speed of the boats and increasing the time required to recharge batteries.

Bubnov’s main competition came from an American firm, the Holland Torpedo Boat Company, whose designs were preferred by the Naval General Staff. In 1911 three Narval-class boats (1911–16, 621/994 tons) were laid down for the Black Sea Fleet using a Holland design; they are frequently described by Russian sources as the best submarines in the fleet. During the war, AG (Amerikanskii Golland, i.e., American Holland) boats were ordered; this design was an international favorite, and no fewer than seventy-one boats of this general type served in the Russian, British, American, Italian, and Chilean navies. Although of an American design, the Russian boats were prefabricated in Canada to circumvent neutrality laws; they were delivered in railway-transportable sections to Vladivostok and assembled in shipyards in Petrograd and Nikolaev. The Russians ordered seventeen boats, although six were subsequently canceled; of the eleven delivered, six entered service with the imperial navy, five in the Baltic and one in the Black Sea. After 1918 the Soviet regime completed five more of the class.

One boat was neither a Bubnov nor a Holland design—the submarine minelayer Krab, built for the Black Sea Fleet to a design of the railroad engineer M. P. Naletov. During her long construction period she was subjected to many alterations, and the resulting boat was so plagued with problems that her crew nicknamed her the “box of surprises.”5 Nevertheless, her ability to lay up to sixty mines unseen by the enemy made her so useful that two of the Bars-class boats under construction for the Baltic Fleet, the Ersh and Forel, were redesigned to carry forty-two mines; only the Ersh entered service, but only in December 1917, and consequently took little part in wartime operations.

Antisubmarine

On 11 October 1914 cruiser Pallada was lost with all hands after being torpedoed by U 26; this tragedy led to a desperate search for effective antisubmarine weapons. As in other navies, consideration was given to a wide, and sometimes bizarre, assortment of expedients, few of which proved to be effective. A great deal of time and money was expended on various types of indicator nets, mine nets, and antisubmarine sweeps, but none seem to have scored any successes (although there is a slim chance that UC.15 was lost in the Black Sea by fouling a mine net). Diving shells, with flat or hollow noses to prevent ricochets, were used against both submarines and torpedoes, and some successes against the latter were claimed; in October 1916 the battleship Panteleimon (ex–Kniaz Potëmkin Tavricheskii) apparently destroyed a torpedo launched at her by UB 7.

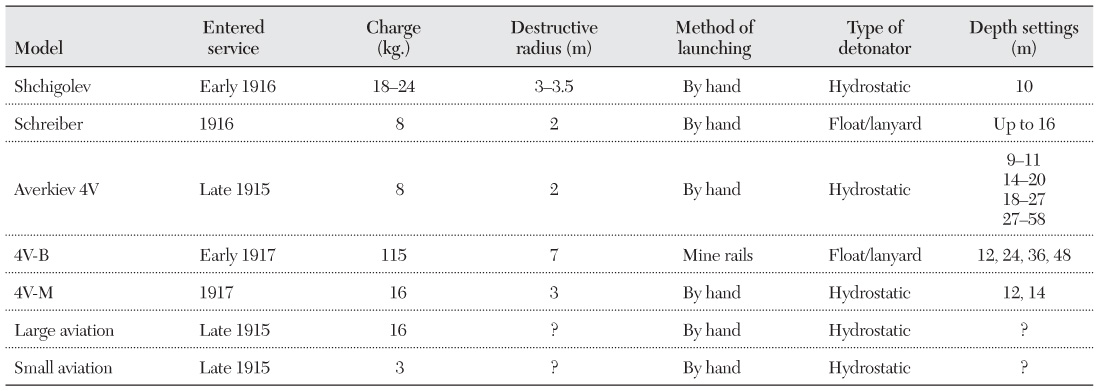

A variety of depth charges were developed using two types of detonators—hydrostatic and float/lanyard. Both types proved problematic, the first because the explosion of one charge tended to set off any others in the water, the second because the charges had a tendency to explode before reaching their preset depths.

Ultimately, Russia’s most successful antisubmarine weapon was the mine. Of the nine U-boats probably destroyed by Russian actions, the losses of six are attributed to mines. After his appointment as commander of the Black Sea Fleet in July 1916, Vice Admiral A. V. Kolchak engaged in a particularly aggressive antisubmarine minelaying campaign, which seems to have paid off: mines destroyed three U-boats in November–December 1916. (See table 6.12.)

Mine Warfare

Doctrine

The Russians were early practitioners of mine warfare and by 1914 were acknowledged masters of its techniques. Mining obviously played a key role in Russian defensive strategy, but it was recognized from the start that an unprotected minefield would soon be swept by the enemy. Therefore mines were usually integrated with coast batteries into “mine-artillery positions.” As for offensive minelaying operations off an enemy’s coasts, stealth was the chief objective. The Baltic Sea’s long winter nights were ideal for such operations, and Russian ships would do everything possible to keep their presence secret, even to the point of refusing to open fire on enemy vessels encountered as long as they themselves were unobserved. The results justified the efforts expended: more enemy vessels were lost to mines than to any other weapon in both the Baltic and Black Sea theaters. The most spectacular success was the virtual destruction of the German X Destroyer Flotilla when it attempted to penetrate the “Forward Position” (see below) on the night of 10–11 November 1916. Seven of its eleven modern destroyers—V 25, S 57, V 72, G 90, S 58, S 59, and V 76—were sunk on Russian mines at the entrance to the Gulf of Finland.

Ships/Weapons

Extensive minefields were used in defense of the Gulf of Finland, for which purpose the Ladoga, Narova, and Onega were converted from old armor-belted cruisers; between them they could carry more than two thousand mines. Most cruisers and destroyers were equipped for offensive minelaying missions.

Table 6.12 Russian Depth Charges

Note: The large charge of the 4V-B could damage a slow vessel before it could get far enough away, so it was used only from fast ships.

Source: D. Iu. Kozlov, “Pervye otechestvennye glubinnye bomby,” Gangut, no. 20 [1999], 68–77.

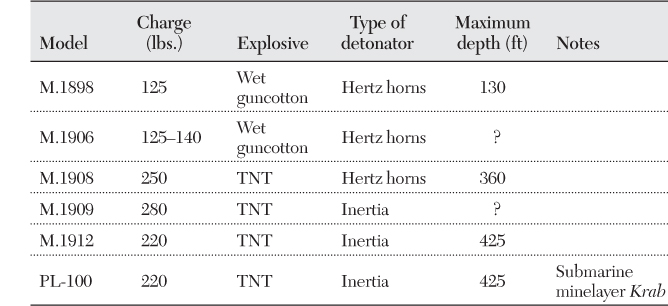

The most numerous type of mine available at the outbreak of war was the M.1908; substantial numbers of the M.1898 were still in service, as well as some M.1906 mines. The M.1909 introduced an inertial detonator in place of Hertz horns, making the mines safer to handle on deck, while the M.1912 had a timing mechanism that delayed the mine’s rise from the bottom. During the war antisubmarine mines were also developed, in which a single mine cable supported three or four mines at different depths. (See table 6.13.)

Source: Iu. L. Korshunov, Iu. L. D’iakonov, and Iu. P. D’iakonov, Miny rossiiskogo flota, Morskoe oruzhie 5 (St. Petersburg: Gangut/Neptun, 1995), 23; Beskrovnyi, Armiia i flot Rossii v nachale XX v., 204.

Amphibious Warfare

Doctrine/Capabilities

In the late nineteenth century the Russian army and navy worked out elaborate plans to seize the Bosporus. These schemes fell into abeyance after the Russo-Japanese War, but during the First World War the Black Sea Fleet did carry out a number of highly successful amphibious operations on a smaller scale. Between February and June 1916, a series of landings along the northern Anatolian coast succeeded in dislodging the Turks from one strong position after another at little cost. These operations were supported by the Black Sea Fleet’s Batumi group, usually consisting of the battleship Rostislav plus gunboats and torpedo boats, sometimes assisted by the battleship Panteleimon. Techniques were developed for controlling naval gunfire from observation posts ashore.

Two special types of craft were used in these landings. One, the Elpidifors, was a group of small cargo vessels (circa one thousand tons) widely used in the Sea of Azov; a number of them were taken over by the navy, and their shallow drafts and large holds made them ideal for use as landing ships. The type proved so successful that the navy ordered thirty of them in early 1917. Also employed in the landings from May 1916 onward were 255-ton landing barges; these were based on the British X Lighters used in the Dardanelles but were somewhat larger. Like their prototypes, they featured bow ramps, lowered by means of booms. Nicknamed “bolinders,” after the Swedish firm that supplied most of the diesel engines that propelled them, fifty of the craft were ordered in December 1915 from the Russud yard in Nikolaev. The first of these became available in March 1916; due to shortages, thirty of them were delivered without engines and were used as barges.

From 1916 onward plans were revived for an assault on the Bosporus, and in July 1916 the emperor personally ordered the new fleet commander, Vice Admiral Kolchak, to make preparations for such a landing. However, in August 1916 Romania joined the allies and promptly collapsed, forcing the Russian command to use the troops intended for the landing to shore up its new ally. In March 1917 the idea of a Bosporus assault was revived, the Turkish defenses having been considerably weakened by the dispatch of troops to other fronts, leaving only two divisions to guard the strait. The new proposal called for a surprise assault using only three divisions, but this was aborted by the turmoil that followed the February Revolution of 1917.

There was far less interest in amphibious operations in the Baltic. Only one small operation was carried out, when 536 men were landed on 22 October 1915 at Petragge, in the Gulf of Riga; this was little more than a diversionary raid behind German lines, and the troops were reembarked later the same day. In July 1916 the navy proposed a much larger landing at Domesnäs, well behind German lines. If successful, the operation might have forced the Germans to withdraw from a large segment of the Baltic coast, but the army rejected the plan.

Coastal Defense

The maritime approaches to St. Petersburg had long been guarded by the fortress of Kronshtadt, which throughout the nineteenth century was regarded as one of the strongest fortified places in the world. But by 1905 Kronshtadt’s forts were obsolete, and when work was begun in 1909 on modernizing the capital’s defenses, a new position was established about forty miles west of Petersburg, where the Gulf of Finland suddenly narrows like the neck of a wine bottle to a width of about twelve miles. On the northern coast was Fort Ino, on the southern side Krasnaia Gorka; their armament was virtually identical, each with eight 10-inch long guns and eight high-angle 11-inch howitzers, plus a variety of smaller weapons. In 1911 it was decided to add 12-inch/52-caliber guns to their armament. Initially, four guns were installed at each fort in open batteries; another four guns, in two twin turrets, were mounted during the war.

At the same time work was begun on the fortifications farther to the west, at the entrance to the Gulf of Finland. Initially under army control, this complex was turned over to the navy in 1912 and named the Maritime Fortress of the Emperor Peter the Great. This was to be the main line of defense, with powerful coastal batteries flanking deep minefields that would span the thirty-mile-wide reach between the Finnish Porkkala Peninsula and Revel on the Estonian side. The complex would thus protect not only the Gulf of Finland itself but the navy’s new main base at Revel.

The start of the war found the Peter the Great fortress far from completion, and during the war the defenses were gradually strengthened using whatever artillery was available. By 1917 guns ranging in caliber from 12-inch to 57-mm had been installed in numerous batteries, creating a formidable defensive position.

The war also led to the extension of the defenses to include the Gulf of Riga, in particular its southern entrance, the Irben Strait. Although after the spring of 1915 the southern coast of the strait was in German hands, on the southern tip of Ösel Island’s Tserel (Zerel) Peninsula four 12-inch/52 guns were installed on open mountings, with numerous smaller batteries at other sites throughout the Moonsund Islands.

Coast defenses in the Black Sea were on a considerably smaller scale. The most important fortifications, which included 280-mm and 243-mm guns, guarded Sevastopol. Odessa and other ports had more modest defenses. During the war, 10-inch guns were installed at Batumi, to defend this forward base and the ships sheltering there against any sudden attack by the Goeben. A few coastal batteries were also established in north Russia during the war to fend off any raids by German auxiliary cruisers.

Aviation

Although the Russian navy had began experimenting with balloons and man-lifting kites well before the Russo-Japanese War, interest in heavier-than-air craft seems to have been slow in developing. A naval air service was established in the Black Sea Fleet only in the autumn of 1911, with the Baltic Fleet following suit in March 1912. Since aircraft were seen primarily as reconnaissance tools, naval aviation was subordinated to the Service of Observation and Communications in both seas. In November 1916, however, aviation was reorganized and transferred to the direct control of the fleet commanders.

Russian naval aviation fought two very different wars. In the Baltic, the task was to support the fixed defenses of the Gulfs of Finland and Riga; reconnaissance was the primary focus. Major naval air stations were established at Kilkond (on Ösel Island) and Abo, in Finland; smaller stations were set up to act as forward operating bases. When she joined the fleet in February 1915, the Baltic Fleet’s sole aviation vessel, the Orlitsa, acted as a mobile base, operating her aircraft from harbors and bays.

In the Black Sea, on the other hand, aviation was used offensively, in raids against Turkish and Bulgarian ports—especially the coal port of Zonguldak and the U-boat base at Varna. The aviation vessels went to sea with the fleet, bombing the enemy and spotting gunfire. The Black Sea fleet had formed what amounted to the world’s first “carrier-battleship task force.”6 It was a force used with a considerable degree of imagination and aggressiveness.

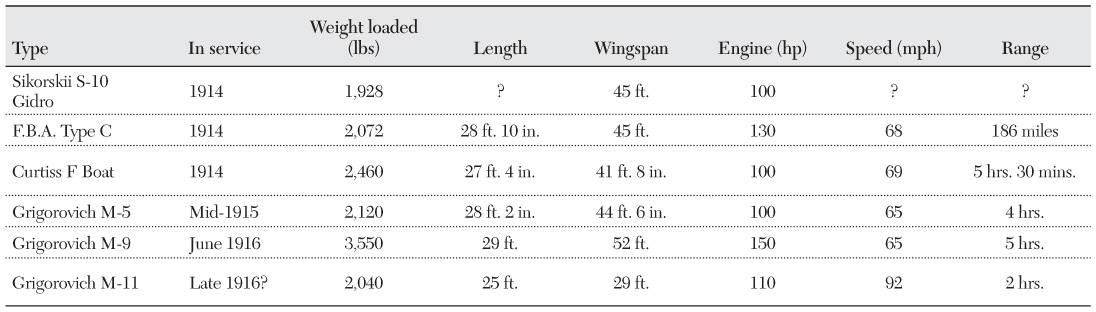

Seaplanes—either floatplanes or flying boats—were seen as the best type for naval service. In the first year of the war the Baltic Fleet used Sikorskii S-10 floatplanes and French-designed F.B.A. Type C flying boats (thirty acquired from France, with a further thirty-four manufactured under license by the Lebedev Works). The Black Sea Fleet used the generally similar American Curtiss Type F; the subsequent Curtiss K-type flying boats proved to be a failure due to flawed design and manufacture. By mid-1915 the M.5, designed by D. P. Grigorovich and manufactured by the Shchetinin Works in Petrograd, was entering service with the Black Sea Fleet. The M.5 was not used by the Baltic Fleet, but its successor, the M.9, which appeared in mid-1916, became the most widely used aircraft in both fleets. By November 1916 there were no less than 121 Shchetinin (Grigorovich) machines of all types serving in naval aviation. Most of these aircraft were powered by foreign-made engines, since Russian industry could manufacture only small numbers of aero engines.

As the war continued fighters became necessary, and in response Grigorovich developed the M.11, an attempt at a flying-boat fighter, but it was outclassed by increasing numbers of German high-performance land planes, especially in the Baltic. This led the navy to acquire small numbers of land-plane fighters for the defense of its bases; in 1917 there were eight naval fighters in the Baltic and two in the Black Sea. By this time the total number of aircraft in service was 269, with eighty-eight in the Baltic Fleet, 152 in the Black Sea Fleet, and twenty-nine in the Naval Aviation School. The revolutions of 1917 and the outbreak of civil war in 1918 led to a rapid deterioration, and by October 1918 the Bolshevik naval air service could muster only sixty-one aircraft.

Mention should also be made of the biggest seaplane of the day—a four-engine aircraft, Ilia Muromets, designed by Igor Sikorskii and fitted with floats. Unfortunately, this machine was destroyed by accident in the first days of the war. Had it survived it might have proved its value in long-range reconnaissance, but for reasons that are unclear the navy ordered no more of these advanced machines, although the wheeled version saw extensive service with the army’s air force.

There was also a short-lived experiment with lighter-than-air aviation: four British Coastal-type nonrigid airships, intended for antisubmarine patrolling, arrived in disassembled form at Sevastopol in late 1916. However, a series of accidents, due both to mishandling and weather, led to the abandonment of this type of aircraft after a short time. (See table 6.14.)

Table 6.14 Principle Aircraft Types of the Russian Navy, 1914–18

Wartime Evolution

The Baltic

In essence, the war in the Baltic was a question of position. Thanks to geography, Germany was able to block maritime communications between the Baltic and the North Sea, except for the passage of a few British submarines. Although the Germans regarded the Baltic as a secondary theater, they could still bring overwhelming force to bear by shuttling ships from the North Sea via the Kaiser Wilhelm (Kiel) Canal. On the other hand, and again thanks to geography, the Russians were able to establish strong defensive positions at the entrances to the Gulf of Finland and the Gulf of Riga. The latter in particular became an object of at least intermittent German interest.

Positional warfare meant minefields, and over the course of the war the Baltic Fleet would lay about 35,000 mines in defensive barriers. The process began on 31 July 1914—the day before Germany declared war—when 2,129 mines were laid to block the entrance to the Gulf of Finland. This was the first installment of the “Central Position,” where any German thrust into the gulf would be met. The German plan, on the other hand, was basically a bluff—active use would be made of second-rank vessels to hold the Russians at bay. However, the bluff was revealed when the light cruiser Magdeburg ran aground on Odensholm Island on 26 August 1914 and documents captured on board the ship revealed the weakness of the German forces in the Baltic. This gave Admiral N. O. Essen, the Baltic Fleet commander, the ammunition he needed to gain approval for a more active policy. From late October 1914 to mid-January 1915 (when ice conditions forced a halt) the Baltic Fleet undertook thirteen offensive minelaying operations, laying a total of 1,538 mines off Germany’s Baltic ports. One of these mines sank the armored cruiser Friedrich Carl on 17 November 1914.

The treasure trove of documents captured on board the Magdeburg included her codebooks; sending one copy to the British, the Russians retained a second copy and made arrangements to exploit it. The resulting decryption of German radio messages allowed the Russians to avoid losses that might otherwise have been crippling. Thus when patrols to the west of the Central Position were halted after the armored cruiser Pallada was sunk by U 26 on 11 October 1914, the fleet relied entirely on radio intelligence for warning of a German approach. By 1916 aircraft were also playing an important role in reconnaissance.

The connection between the war on land and the war at sea was clearly shown in the summer of 1915, when the Central Powers overran most of Russian Poland. By July the Germans were at the gates of Riga; if the hastily constructed front there collapsed, Russian control of the Gulf of Riga would be lost, opening the back door to the Gulf of Finland. Russian naval intelligence learned of German plans to seize control of the gulf, and the local defenses were strengthened: minefields were laid in the Irben Strait (the southern entrance to the Gulf of Riga), and the predreadnought Slava was sent there to assist in protecting the fields. Thus when the German assault came in August 1915, the Russians could offer strong resistance. Although the Germans did briefly penetrate into the gulf, they were eventually forced to withdraw. Henceforth the navy would render strong support to the army’s Riga front, which may well have been the decisive factor in keeping that area stable for more than two years.

By the time of the Riga offensive Admiral Essen was dead of pneumonia, and Vice Admiral V. A. Kanin commanded the Baltic Fleet. He intensified the war against Germany’s trade with Sweden, both by submarines and surface ships, although these efforts never posed a serious threat to that trade. Another development during his tenure was the Forward Position, a new mine-artillery position to the west of the Central Position that deepened the Russian defensive system.

In September 1916 Kanin had been replaced by Vice Admiral A. I. Nepenin, who had previously commanded the SNIS. Nepenin planned a more active role for the fleet in the 1917 campaign; in the meantime, he tried to restore discipline, which had lapsed during Kanin’s tenure. Unfortunately, the crews saw his efforts as persecution, and this added to the resentment building on the lower deck. Throughout the war there had been minor incidents of indiscipline, most notably on board the dreadnought Gangut on 1 November 1915, when the crew rioted after being denied its expected meal of meat and macaroni after coaling ship. By the winter of 1916/17 the situation, not only in the fleet but throughout Russia, was moving toward a crisis. Under the influence of the mystic Grigory Efimovich Rasputin, Empress Alexandra urged her husband to replace one minister after another. Nicholas, at Stavka, usually agreed; the disorganization in government spread to the transportation system, which began to break down under the stress of war. In early March 1917 (late February, by the Russian calendar) riots over a lack of bread in Petrograd turned into a revolution as troops joined the protests. Within days the monarchy collapsed, replaced by competing authorities—the liberal Provisional Government and the radical Petrograd Soviet of Workers’ and Soldiers’ Deputies.

News of the revolution ignited mutinies at most of the Baltic Fleet’s bases; at Helsingfors forty-five officers were murdered, among them Admiral Nepenin; at Kronshtadt twenty-four officers perished; at Revel, where the more active destroyers and submarines were based, only five were killed. Many more officers were forced off their ships. Almost overnight sailor committees took charge of running the ships, and although the remaining officers were theoretically in charge of military activities, their authority was continually undermined. By the autumn of 1917 the fleet had lost much of its combat effectiveness. It did, however, manage to fight one last battle. On 11 October 1917 the Germans launched Operation Albion, the invasion of the Moonsund Islands, which guarded the Gulf of Riga. Within hours the army units ashore had started to collapse, but the navy continued to resist until forced to abandon the gulf on 19 October.

The Bolsheviks seized power in November 1917 (the October Revolution, again according to the Russian calendar), and on 15 December 1917 they signed an armistice with the Central Powers at Brest-Litovsk. However, the ensuing peace negotiations soon deadlocked in the face of Germany’s severe demands; therefore, on 18 February, the Central Powers launched an offensive that compelled the Bolsheviks to submit to the German terms. The Treaty of Brest-Litovsk (3 March 1918) was harsh; its naval terms obligated Russia either to keep its ships in Russian ports until the end of the war or, if this was impossible, disarm them immediately. This placed the bulk of the Baltic Fleet, locked in the ice at Helsingfors, under an immediate threat, since the “White” Finns, supported by the Germans, were fast approaching. This led to the famous “Ice Passage,” a series of evacuations assisted by icebreakers, that brought all the big ships and most of the smaller ones to Kronshtadt between 12 March and 11 April 1918. The Baltic Fleet’s ships thereafter did nothing of note, aside from laying defensive minefields to the west of Kronshtadt in August 1918; these were meant to deter the Germans, if they were tempted by Russian weakness to seize the ships or Petrograd itself. With that, the naval war in the Baltic came to an end—at least until the arrival of British forces in 1919.

The Black Sea

When the First World War erupted, Turkey initially remained neutral, despite the arrival of the German battle cruiser Goeben, which, along with her consort, the light cruiser Breslau, entered the Dardanelles on 10 August 1914 to escape their British pursuers. Tension in the Black Sea mounted over the next several months, and on 29 October 1914, without a prior declaration of war, Turco-German naval forces launched a series of attacks on Russian ports—Odessa, Novorossiisk, Feodosiia, and Sevastopol, where Goeben briefly bombarded the harbor before being driven off by the accurate fire of the coast-defense batteries.

Although the Russians had been caught napping, their loses were small. If the war in the Baltic was one of positions, the Black Sea offered scope for the classic concept of command of the sea, and the outbreak of war placed the Germans and their Turkish allies in a very exposed position. Although the Goeben was the most powerful ship in the Black Sea and faster than any Russian ship, these were only temporary advantages, for the Russian dreadnoughts building in Nikolaev would outgun her, and the new Novik-type destroyers could outrun her. Moreover, the Ottoman Empire had few railways or paved roads, so Constantinople was dependent to a considerable degree on seaborne supplies, especially coal, most of which came from Zunguldak, about 150 miles east of the Bosporus on the northern Anatolian coast. Moreover, Enver Pasha, the Turkish minister of war, had launched an ill-advised offensive into the Caucasus, which could be supplied only by sea. These maritime lines of communication were open to attack by the Black Sea Fleet.

Until the Black Sea Fleet’s new ships entered service, however, the Goeben was more powerful than any of its ships and faster than all save for the new destroyers that were just entering service. Only the united force of the predreadnoughts could survive an encounter with the German battle cruiser. This was shown clearly when the Goeben intercepted the main force of the Black Sea Fleet off the southern Crimea on 18 November 1914. Although the German ship scored four hits on the Russian flagship, she was forced to retire when a Russian shell hit her secondary battery, starting a fire that nearly spread to a magazine. The battle cruiser would in future avoid confrontations with the united Russian squadron.

Immediately after the outbreak of war, the Black Sea Fleet started laying defensive minefields. As for offensive minelaying, the first operation off the Bosporus was badly botched, but subsequent efforts proved more successful; on 25 December 1914 the Goeben fouled two mines and had to limp back to Constantinople, where she was under repair for several months. The Russians meanwhile undertook a series of raids, on the coal facilities at Zunguldak and at the Bosporus itself. The big new Russian destroyers began making sweeps along the Anatolian coast, sinking or capturing any Turkish vessels they encountered, leading one German officer to complain that the “Russian destroyers with their artillery and speed are the real masters of the sea and need fear no one.”7 In April a Turco-German bombardment of Odessa went seriously awry when the cruiser Mecidiye sank in shallow water after straying into a Russian minefield; she was later raised and incorporated into the Russian fleet under the name Prut. In July the Breslau was damaged on a Russian mine, putting her out of action for several months.

The year 1915 also saw the start of submarine warfare in the Black Sea. The Russians received their first effective submarine in March 1915, when the Nerpa entered service; she was soon joined by others. The boats were for the most part employed off the Bosporus, but they proved less effective than the destroyers in blockade duty—their range of vision was too small, and their speed was too low. On the Turco-German side, the first U-boat, UB 7, arrived in July from the Mediterranean, and more followed. The threat of the U-boats had a marked impact on Russian operations, the big ships being used more cautiously.

On 6 October 1915 Bulgaria joined the Central Powers. Although its navy was insignificant, the port of Varna soon became an important U-boat base, which provoked the Russian fleet to bombard it several times. In these and other operations the Russians made use of their seaplane carriers, with the aircraft carrying out bombing attacks as well as spotting naval gunfire.

By this time the first of the Black Sea dreadnoughts, Imperatritsa Mariia, had joined the fleet. Her sister Imperatritsa Ekaterina Velikaia entered service in December and on 8 January 1916 had a brief encounter with the Goeben, which managed to escape the more powerful Russian ship thanks to superior speed. But the Russians could now field three maneuvering groups each more powerful than Goeben—one built around Mariia, another centered on Ekaterina, and a third with the fleet’s three most modern predreadnoughts, Evstafii, Ioann Zlatoust, and Panteleimon. Moreover, the Russian blockade of the Bosporus was increasingly effective, and coal was in short supply in Constantinople; the Goeben’s sorties into the Black Sea became less frequent.

Throughout the spring and summer of 1916 the Russian army advanced into Anatolia, supported along the coast by a series of amphibious landings. These repeatedly turned the Turks’ flank, forcing them to abandon otherwise strong positions. The Russians were also able to reinforce and supply their army by sea, a luxury denied the Turks.

But Goeben was by no means out of the war, and in early July 1916 she managed to evade a Russian trap, thanks again to her speed. For the Russian high command this was the last straw; Admiral Ebergard, who was increasingly at odds with the naval staff at Stavka, was replaced by the energetic Vice Admiral Kolchak. The new commander initiated an aggressive offensive minelaying campaign, which by the end of the year had crippled U-boat operations in the Black Sea; he also undertook preparations for a landing at the Bosporus.