![]()

Beyond the fleets of the major belligerents, others navies had the potential to significantly contribute to war operations but for one reason or the other did not.

As a result of South America’s regional arms race, Brazil initiated a major building program in 1904 and ordered two dreadnoughts from British yards. While this gave the appearance of a burgeoning naval power, Brazil then suffered a remarkable reversal of economic fortune. A third battleship ordered from Britain had to be sold while building, and the completed ships suffered utter neglect. An advisor dispatched by the United States learned that battleships Minas Gerais and São Paulo had not fired their guns at all since their delivery in 1910, nor had their boiler tubes ever been cleaned.1 Boiler problems associated with disuse hamstrung nearly the entire surface fleet. Not surprisingly, when Brazil declared war against Germany in 1917 in response to U-boat attacks, the navy had little to contribute. A cruiser-destroyer detachment operated out of Dakar for the final three months of the war.

Greece too had some naval potential, having just bested the Ottoman fleet in the First Balkan War and displaying enough ambition to buy two used battleships from the United States. However, the country found itself caught between its king’s pro-German inclinations and pressure from the allies. The French effectively settled the matter by seizing the Greek navy in October 1916. The largest Greeks units were demilitarized, while the French took over the most important light units. Thus it was Greece’s ports that made the nation’s largest contribution to the naval war.

There were two countries, however, that warrant attention: one whose vast fleet was little utilized and one whose outnumbered navy could only hope to manage the challenges it faced. These were the navies of Japan and the Ottoman Empire.

JAPAN

By the start of the First World War, Japan had completed a fifty-year transformation from a preindustrial hermit kingdom to an international power. The fleet had played a major role in this process, scoring key victories in the successful wars against Japan’s two principal and theoretically stronger regional foes, China (1894–95) and Russia (1904–1905). In contrast, the Japanese Imperial Navy saw limited participation in the Great War but nevertheless obtained valuable operational experience and impressed its allies with the quality of its ships and men.

Pre-1914 History

The Japanese Imperial Navy was formed in the 1870s as the threat of European imperialism forced Japan’s leaders to modernize the nation’s industry and military and make self-defense the immediate priority. The incipient navy took its cues from France’s Jeune École doctrine, which focused on trade war and coast defense with cruisers supported by swarms of expendable torpedo boats. The Japanese ordered one armored and six protected cruisers from British and French shipyards during the 1880s. By 1885, plans called for forty-six torpedo boats, and though finances restricted construction to only twenty-five, Japanese yards themselves completed a handful of these boats.

The 1890s brought dramatic change. Tension with China and concern over Russia’s expansionist policies prompted the navy to develop a fleet capable of intervening overseas. This process coincided with the publication of The Influence of Sea Power upon History, Alfred Mahan’s treatise on naval philosophy that influenced planning in all major navies. Mahan stressed the primacy of the battleship fleet and taught that this fleet should defeat its enemy counterpart to establish command of the sea. The Japanese found much here that applied to their situation as an island nation dependent upon overseas commerce, and they became convinced that the “aim of a naval engagement was the total annihilation of the enemy fleet in a decisive battle.”2 The decisive-battle concept crystallized as a permanent fixture in Japan’s naval planning and dictated construction plans for decades to come.

Japan’s first battleships, of the Fuji class, were laid down in British yards in 1894. That same year war erupted with China. A force of Japanese cruisers and gunboats trounced the Qing fleet at the battle of the Yalu River on 17 September 1894. This and the subsequent naval blockade of China’s main harbor at Weihai guaranteed victory. However, after the war, Germany, Russia, and France prevented Japan from retaining Port Arthur and the Liaotung Peninsula, the principal reward Tokyo had expected from its triumph. This humiliating intervention accelerated Japan’s naval expansion. Russia’s subsequent lease of Port Arthur and its muscle-flexing in Korea confirmed Japan’s perception that it needed to control the seas of East Asia for its own security.

In 1902 Japan negotiated a treaty with the world’s premier power, the United Kingdom. The two signatories agreed to respect each other’s special interests in China and Korea, to remain neutral if either signatory went to war with one enemy and to support the other if either became involved in war with multiple enemies. This treaty certified Japan’s status as a great naval power and guaranteed that no coalition of European powers would steal the fruits of its next victory.

War with Russia came two years later. Instead of a mélange of cruisers and gunboats, the Japanese navy deployed an elite battle line: six battleships and eight armored cruisers supported by ten modern protected and unprotected cruisers, sixteen older cruisers, six gunboats, twenty destroyers, and fifty-seven torpedo boats. On 27–28 May 1905 this fleet defeated the Russian navy in the landmark battle of the Tsushima Straits, one of the most decisive naval victories in modern history.

Victory over the two greatest foreign threats did nothing to forestall another war from taking place at home. Japan’s national constitution granted cabinet posts to the army and navy, each having the power to bring down a government; the savagery of their political and budgetary rivalry ensured that each service would endlessly seek pretexts to trumpet its own importance. Remarkably, the 1907 Imperial National Defense Policy, rather than correcting this duality, formalized it by designating two different countries as the primary threat to Japan: Russia (according to the army) and the United States (according to the navy).

The oceanic expanse separating Japan from the United States represented not a buffer but the only direction for Japanese expansion that granted the navy top billing. Hostility with America had simmered since the Hawaiian crisis of 1893, and American policy toward Japanese emigrants caused considerable offense. Both countries jealously guarded their interests in China. Even Mahan, so instrumental in the formation of Japanese naval policy, presented a problem; the popularity of his views in America gave a menacing hint of naval aspirations there. Japanese planners calculated that a proper defense necessitated a fleet equaling 70 percent of U.S. strength, and this gave birth to an “Eight-Eight-Eight Fleet” policy—eight new battleships and eight new battle cruisers built every eight years.

The 1911 renewal of the Anglo-Japanese alliance came with a hitch, as London insisted on a new clause removing any obligation for either country to fight the United States. The treaty thus lost much of its value for the Japanese, though it ensured continued Japanese access to some British technology. The Royal Navy had, in fact, already classified Japan as a future threat and stopped sharing secret information, like advanced fire-control methods and mechanisms, since 1909.3

Of course, the ultimate goal was freedom from reliance on any other fleet, and the Mahan-inspired “big ships, big guns” policy took hold in domestic warship construction, within the limits of that industry’s capabilities. Two units of the Satsuma class (19,372 tons normal displacement; four 12-inch/45-caliber guns; twelve 10-inch/45; 18.25 knots) began construction in 1905 and were sources of great national pride, as the largest battleships in the world—at least until the British rushed their battleship Dreadnought into service, with its firepower concentrated in a battery of ten 12-inch guns, which became the pattern for all modern battleships. In fact, an early draft of the Satsuma design featured a uniform main battery like Dreadnought’s, but the technical challenge proved too intimidating for the Japanese. Likewise, Japan laid down a mighty foursome of armored cruisers, the Tsukuba and Kurama classes, armed with the same four 12-inch guns that a battleship would carry, only to see Britain commission Invincible with eight 12-inch guns. This was such a revolutionary step in cruiser development that Invincible and her sisters received a new rating as “battle cruisers,” a label the Japanese quickly pinned onto the Tsukubas and Kuramas despite their obvious inferiority to Invincible.

Japan finally commissioned its first dreadnoughts in 1912—more than five years after Dreadnought herself—completing Kawachi and Settsu (21,443 tons; twelve 12-inch guns; twenty knots) with 12-inch guns at a time when the British already had ships with 13.5-inch and the Americans 14-inch guns. The larger calibers completely derailed Japan’s battle-cruiser program, and Tokyo accepted the humbling but pragmatic solution of importing from Britain not only a new ship but also shipbuilding expertise. Kongo, the last Japanese capital ship built overseas, reached completion in 1913—the largest warship in the world, mounting the largest guns. Thereafter the Japanese were able to complete her three sister ships in domestic yards. This acquisition advanced Japanese naval technology in other ways: domestically constructed fire-control directors and range clocks of Vickers design appeared in 1915. Nonetheless, the Japanese remained well behind British standards of fire control throughout this period.

Japan went on to launch two Fuso-class battleships, even larger than Kongo, in 1914–15 and then two Ise-class ships in 1916–17. By 1917, when the Japanese laid down Nagato, which would become the first dreadnought with 16-inch guns (actually 410-mm), they were completely independent of British tutelage

Japan at War

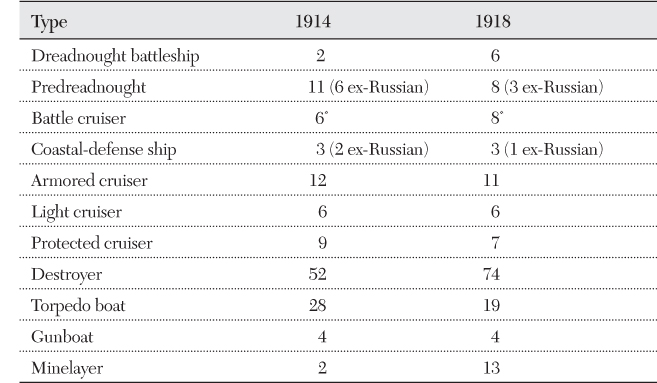

Geography dictated that Japan’s participation in the Great War at sea would not be commensurate with the size of its navy, even admitting the artificial inflation of its fleet list with old Russian vessels. (See table 8.1.)

Table 8.1 Japanese Navy, August 1914 and August 1918

Type |

1914 |

1918 |

Dreadnought battleship |

2 |

6 |

Predreadnought |

11 (6 ex-Russian) |

8 (3 ex-Russian) |

Battle cruiser |

6* |

8* |

Coastal-defense ship |

3 (2 ex-Russian) |

3 (1 ex-Russian) |

Armored cruiser |

12 |

11 |

Light cruiser |

6 |

6 |

Protected cruiser |

9 |

7 |

Destroyer |

52 |

74 |

Torpedo boat |

28 |

19 |

Gunboat |

4 |

4 |

Minelayer |

2 |

13 |

* Including the Tsukubas and Kuramas.

After declaring war on the Hohenzollern and Habsburg empires, the United Kingdom called upon Japan to honor the 1911 naval agreement. Japan saw a golden opportunity to advance its position in East Asia and on 15 August 1914 demanded that Germany surrender its holdings on China’s Shandong Peninsula and in the Caroline, Mariana, and Marshall Islands, and also order all warships to evacuate the Pacific. Germany predictably failed to comply, and Japan declared war on 23 August.

Supported by a small British contingent, the Japanese navy landed 30,000 men on the Shandong Peninsula, besieged the Germans at Qingdao, and ultimately captured the city on 7 November 1914. Three naval squadrons—the 1st, Southern, and American Expeditionary—were formed ostensibly to hunt for Admiral Maximilian Spee’s German force. The first two squadrons also occupied Germany’s island possessions north of the equator. The latter formation patrolled the Pacific coast of South America until March 1915, when a British squadron sank the light cruiser Dresden off Chile.

When the German light cruiser Emden appeared in the Indian Ocean, the cruiser Chikuma sailed there. The battle cruiser Ibuki escorted the thirty-eight transport “Anzac Convoy” across the Indian Ocean to Aden. The Japanese 3rd Squadron, consisting of several cruisers, operated from Singapore; at the request of the Royal Navy, it patrolled the waters of Australia and New Zealand in late 1914 and again between March 1916 and December 1917. Its biggest action came in February 1915, when a landing party assisted in suppressing a mutiny of Indian troops at Singapore. After December 1917 the 1st Special Squadron assumed responsibility for Indian Ocean shipping lanes.

Though the Japanese sent personnel to serve with the Royal Navy (some of them dying at Jutland), they firmly resisted requests for ships in European waters. The desperate British then tried to buy two of the Kongos, even sweetening the offer with two Royal Navy battleships in exchange. The Japanese were unmoved. Only when the British pledged postwar support for Japan’s claims on its captured German territories was an agreement reached. In April 1917, two cruisers transferred to Cape Town and the 2nd Special Squadron deployed to Malta. The Mediterranean formation (one cruiser and eight new destroyers, eventually growing to two cruisers and fourteen destroyers, including two transferred British H-class units) escorted 788 allied ships in 348 missions. Its ships worked closely with the British and earned an excellent reputation.

Other Japanese vessels served in Europe but under foreign command. Japanese yards exported a dozen 665-ton destroyers to France, and the Italians and French purchased for patrol duties forty-seven and thirty-four former fishing vessels, respectively.

Japan’s warship losses were insignificant. The Qingdao operation cost the torpedo boat Shirotae (grounded then shelled, 3 September) and the old protected cruiser Naniwa (torpedoed and sunk by German T 90, 17 October). The new destroyer Sakaki survived a torpedo hit from the Austro-Hungarian submarine U 27 on 11 June 1917 off Corfu but lost sixty-eight men, including her captain.

The war provided little experience in combat but much in long-range escort and overseas deployment. The 2nd Special Squadron practiced the most modern techniques of antisubmarine warfare—lessons largely overlooked by the high command, which persisted with its fixation on “big ships, big guns.” The June 1918 review of the Imperial National Defense Policy retained the United States as the navy’s chief hypothetical foe, despite the fact the two powers were allies, and the navy determined that only an Eight-Eight-Eight construction program would provide sufficient strength to deal with this potential foe.

Japan’s economy precluded the realization of such plans, but the 1922 Washington Conference transformed all strategic scenarios in any case. While it avoided another naval race like the one preceding World War I, the Washington Treaty galled many in the Japanese navy who saw national security only through unfettered growth in armament. This faction longed for an armed confrontation with the United States, and Japan’s planning for a naval war became a self-fulfilling prophecy.

THE OTTOMAN NAVY

Pre-1914 History

The nineteenth century saw the once-formidable Ottoman navy decline into irrelevance, reflecting not only the fading status of the empire itself but its rulers’ attitudes—the latter ranging from childlike extravagance to active hostility toward the maritime service. In 1890, after defeat in the Russo-Turkish War, Sultan Abdul Hamid II eased his distrust of the navy long enough to approve construction of an 8,100-ton battleship, larger than any previous domestic project; nineteen years later, the still-incomplete hull was cleared from the slip. Perhaps this was not surprising. In 1905 this same sultan explained to the British naval attaché that he preferred submarines over surface ships because they could not aim their guns at his palace.

The 1897 war with Greece revealed the fleet’s impotence, and humiliation prompted the leadership to undertake genuine reform. Momentum increased with rise of the Young Turks and restoration of the constitution in 1908, but stable leadership did not return—the post of navy minister changed hands nine times over the next three years—and other fundamental problems remained.

The national treasury was exhausted. Plans for new construction repeatedly failed because finances could not cover refits of existing units. One ironclad waited in a foreign yard for six years while the navy scrounged for funds. A flotilla of old warships heading for modernization in Germany found itself stuck in Genoa for months pending settlement of Ottoman debts in Italy. The government resorted to public subscription for the purchase of warships in Germany; when that sum proved inadequate, the deal went through only because the sellers noticed that the deposed sultan’s German bank account bridged the gap.

Even worse than the lack of modern ships was the lack of skilled personnel. Decades of naval decline had created shortages at all levels: commanders, enlisted men, strategic planners, and shipbuilders. Administrators often proved more attentive to self-interest than to duty. Crewmen who had brought a ship to Germany for reconstruction were abandoned on board a transport that sat at Kiel for over a year before anyone paid for their return trip. Officers’ commissions, handed out like candy, provided personal income but not necessarily personal responsibilities. A yacht serving as stationary guard ship at Vathi had a crew of thirty-five men, along with thirteen officers—most of whom had never been on board.

As it turned out, those no-show officers were especially fortunate. The yacht became the recipient of battleship gunfire during the 1911–12 war against Italy—only the first losing campaign entangling the Ottomans on the eve of World War I. The subsequent Balkan Wars offered a more winnable naval scenario, which in the end simply made defeat more embarrassing. The Greek victors relied heavily on a single armored cruiser that repeatedly outmaneuvered and frustrated the Turkish Battle Division and its three capital ships.

Despite the navy’s modern history of disorganization, indifference, and wartime disaster, the fleet did manage to acquire some respectable warships, due largely to eager businessmen who hoped that accommodations now might lead to lucrative deals later. Thanks to the efforts of banks in Britain and Turkey, as well as favorable terms from the Vickers yard, the Ottomans ordered a dreadnought, Reşadiye. Optimism rose so high that the fleet formulated a building program including six such ships—without specifics as to their financing or manning. The government duly rejected the plan. Other possibilities arose. A third party tried to procure Brazil’s two dreadnoughts for Turkey in exchange for oil rights in Mesopotamia. This proposal fell through, but Brazil’s antibattleship fervor made available a battleship under construction in Britain. Dealing with the builder Armstrong regarding port privileges in Turkey, the Ottomans managed to buy their second battleship, Sultan Osman-i Evvel. With the navy now enjoying great public support—Greek dreadnought ambitions were well known—policy solidified. The contract for a third dreadnought, Fatih, was signed with Vickers. Work on the ship began less than three weeks before Franz Ferdinand’s assassination.

Table 8.2 Ottoman Navy, August 1914 and August 1918

Type |

1914 |

1918 |

Dreadnought battleship |

0* |

0 |

Predreadnought |

2 |

1 |

Battle cruiser |

1 ** |

1 |

Coastal-defense ship |

2 |

2 |

Armored cruiser |

1 |

0 |

Light cruiser |

1 *** |

1 |

Torpedo cruiser |

2 |

2 |

Sloop/armed yacht |

6 |

4 |

Destroyer |

9 |

6 |

Torpedo boat |

9 |

5 |

Gunboat |

19 |

9 |

Minelayer |

2 |

2 |

* Sultan Osman I (ex-Rio de Janeiro) seized 2 August 1914, the day before being handed over to Turkish control.

** Ex-German Goeben.

*** Ex-German Breslau.

By July 1914 Turkey had numerous foreign orders in place—unfortunately, in countries soon to be enemies. These included six 1,040-ton destroyers and two submarines from France; four 700-ton destroyers from Italy; and from Britain, three battleships, two 3,550-ton protected cruisers, four 1,100-ton destroyers, and two submarines.

In the event, Britain delayed construction of Reşadiye and Sultan Osman-ı Evvel, formally seizing the ships before either country was a combatant. This understandably caused great offense. The British did offer some compensation, but this was hardly sufficient to undo the diplomatic damage. In fact, Constantinople’s lost fleet represented a force far stronger than the one the Ottomans actually operated during the war. Domestic yards had some capability but no longer met modern naval standards. As war nullified plans for British-led shipyard renovation, the Germans eagerly sought to take up the slack, but wartime efforts simply could not negate decades of neglect. In general, local shipyards sufficed only for basic maintenance, repairs, and conversion of merchant craft. Destiny, though, intervened to provide Turkey with a naval upgrade, and it was a game changer.

In 1910 the Ottomans opened discussions with Germany regarding used ships. The armored cruiser Blücher, just entering service with the Germans at the time, earned consideration before ambitions escalated. The new battle cruiser Von der Tann, the newer battle cruiser Moltke, and even a battle cruiser so new it was known only as “H” were all contemplated. But when finances had the final word, the deal settled at two antique battleships and a set of new destroyers. No one could have imagined at the time that “H” would indeed go to Turkey, under her commissioned name Goeben. Commanded by Admiral Wilhelm Souchon and accompanied by the light cruiser Breslau, Goeben reached the Dardanelles on 10 August 1914 ahead of a superior British squadron seeking to bring her to battle. The two ships became Yavuz Sultan Selim and Midilli, respectively, and Souchon became the commander of the Ottoman fleet on 3 September 1914.

The Ottoman Navy at War

Germans would head the navy almost through the end of the war. Hubert von Rebeur-Paschwitz relieved Souchon on 24 August 1917 and served until 3 November 1918, when Arif Ahmet Paşa assumed command. Given Germany’s experience with the complexities of fleet operations, the prominence of German personnel was reasonable, though they experienced some distaste at finding so many of the best-trained Turkish officers to be Anglophiles, a result of the British naval mission that had worked strenuously (though, for the most part, futilely) in Turkey from 1907 to 1910. German officers commanded many Ottoman ships, often with mixed crews.

It was the Turkish government’s pro-German leanings prewar that facilitated wartime cooperation. Goeben had already visited Turkey in 1913, the same year that the Turks invited Germany to send a military mission to the straits. In August 1914, Admiral Guido von Usedom led a group of coast-defense personnel to serve in the Dardanelles and Bosporus installations. German technicians who came to inspect the fleet found the ships in shocking disrepair, even uninhabitable. Turks received technical training in Germany.

As organized in October 1914, the Ottoman navy concentrated its largest vessels in the I Squadron. In addition to Yavuz, this included the three capital ships bested by the Greeks—the armored vessel Mesudiye (9,190 tons) and the two ex-German battleships Torgud Reis and Barbaros Hayredin (10,013 tons). Yavuz completely outclassed her squadron mates, which the Germans considered unfit for sea, but the haste that had sent her to Turkey left her in need of boiler servicing. She lacked the latest fire-control equipment, shells, or propellant, which helps explain how Russian gunfire so easily outranged her. All these problems persisted into 1918 before correction. Active only intermittently and subject to neglect, Yavuz’s greatest importance lay in her merely existing and forcing the Russians to account for her in their plans.

The II Squadron comprised the fleet’s cruiser force. Midilli mostly shared in Yavuz’s fortunes, and like the battle cruiser she far excelled her squadron mates, which included a pair of German-built torpedo-cruisers (775 tons), soundly built but of no decisive merit. The British-built protected cruiser Hamidiye (3,904 tons) enjoyed a fine reputation based on her successful raiding operations in the Balkan War, when she had had only the Greeks to fight. The American-built Mecidiye (3,485 tons) resembled Hamidiye in specifications but suffered from faulty construction that severely compromised her seaworthiness. Coastal raids by the cruisers and Yavuz constituted the only appreciable naval offensive action by the Ottomans during the war.

The I Destroyer Squadron consisted of four new 765-ton German destroyers, the II Destroyer Squadron of four 284-ton French-built destroyers dating to 1907. Humbler still, the I and II Torpedo Boat Squadrons each had four vessels of 97–165 tons. All these units saw extensive service in escort and patrol duty, and the German-built destroyer Muavenet-i Milliye torpedoed and sank an old British battleship. On the other hand, one torpedo boat became a loss when its engines gave out during a pursuit by British destroyers.

The Mine Group included four disparate craft, including one that ranked second only to Yavuz in wartime impact, the 365-ton, German-built minelayer Nusret. On 8 March 1915 she laid some of Turkey’s last remaining mines in the Dardanelles. Ten days later allied battleships tried to force their way through, and the mines sank three predreadnoughts. By securing the Dardanelles and the Bosporus, minelayers achieved the Ottoman navy’s most important strategic success.

The fleet had no submarines operational when war began, though a pair of craft remained from the 1880s; not even the Germans found a way to make them useful. A damaged French submarine (ironically, the Turquoise), captured in 1915, took the name Müstecip Ombaşı but served only as a platform for propaganda and battery charging for German boats. The operation of German submarines from Turkish bases, however, combined with the threat of Yavuz, gave the Russians something more than a nuisance to manage.

For combat against submarines, the Turks eventually received depth charges, but at no time did their efforts accomplish much. Surface craft presented more deterrent than threat. Mines and nets had some value, but coastal guns were the most effective measure in the narrow waters.

Turkey’s miscellany of small craft and auxiliaries worked tirelessly and incurred heavy losses. A collection of vessels on the Tigris and Euphrates, headed by the 422-ton gunboat Marmaris, had little impact on developments there.

Thanks largely to French assistance starting in 1913, the Turkish fleet had an air arm and a seaplane station at the outbreak of the war. In time, both the training and the operational arm acquired German commanders. Though units often transferred to duty with the army, the naval arm maintained its independence. It operated jointly with army fliers in Palestine and performed useful reconnaissance over the straits and the Sea of Marmara, suffering operational losses but none in combat.

Prewar events had evicted the Ottoman navy from the Aegean and Mediterranean. Wartime developments eliminated it as a factor in the Black Sea. Attrition and a lack of maintenance reduced the merchant fleet to near extinction and left allied submarines with a paucity of worthwhile targets. Caught in the pincer of strong allied fleets, the navy could hope only to defend its coasts, and in this limited task it managed heavily qualified success.