Rules of thumb should hardly ever be relied on as a primary appraisal method. Having said that, if there are valuation rules of thumb for an industry, especially if they are widely recognized, they can be useful in a number of ways: as a “sanity check” on a valuation arrived at through other methods; as a means to estimate a ballpark range of value; and within certain industries and in certain litigation contexts, as supporting evidence in court.

Rules of thumb are often classified within the market approach to business valuation because they are thought to have their origins in transactions in the industry. However, their actual origins can vary from pure folklore to (rarely) actual transaction studies.

Speaking to the relationship between rules of thumb and valuations, long-time appraiser Glenn Desmond cautions that valuations change over time in response to changing economic and industry conditions. Furthermore, at any given time, valuations may vary considerably from one locale to another.1

Rules of thumb are usually expressed as multipliers. The most common is a multiple of revenues, such as “Many accounting practices sell for 0.75 to 1.25 times annual revenues.” The other popular multiple for rules of thumb is a multiple of discretionary earnings, also called the seller’s discretionary cash flow (SDCF), or owner’s cash flow (OCF), earnings that may be defined, in certain applications, to reflect earnings of a business enterprise prior to the following items: income taxes, nonoperating income and expenses, nonrecurring income and expenses, depreciation and amortization, interest expense or income, and the owner’s total compensation for those services which could be provided by a sole owner-manager.2

Occasionally, one finds rules of thumb relating to some measure of physical volume. For example, a rule of thumb for taverns might be so many dollars for each keg of beer sold per month. Both the cable and cellular phone industries have been valued at X dollars per actual and/or potential subscriber.

To the extent that rules of thumb are used, they usually apply to small businesses and professional practices. They generally assume that the sale of the business would be on an asset basis rather than on a stock basis. It is generally assumed that the rule represents the transfer of the operating tangible and intangible assets but not the real estate or the current assets or liabilities (for example, cash, accounts receivable, inventory, or accounts payable). Often a covenant not to compete is included, and sometimes an employment agreement. A major problem with rules of thumb is that they are not clear as to exactly what business assets they purport to represent. Furthermore, they do nothing to deal with the essential valuation factors of relative risk and growth prospects.

The rule of thumb values are intended to indicate face values of transactions, not necessarily (or even usually) cash equivalent values. That is, most of the businesses are sold on terms and not for cash. Normally, the seller receives a note for the balance, usually at a rate of interest below market rates for comparable credits and sometimes including contingencies. Thus, if such rules or transactions are used to develop fair market value (which assumes cash equivalency, as discussed in Chapter 13), adjustments need to be made accordingly.

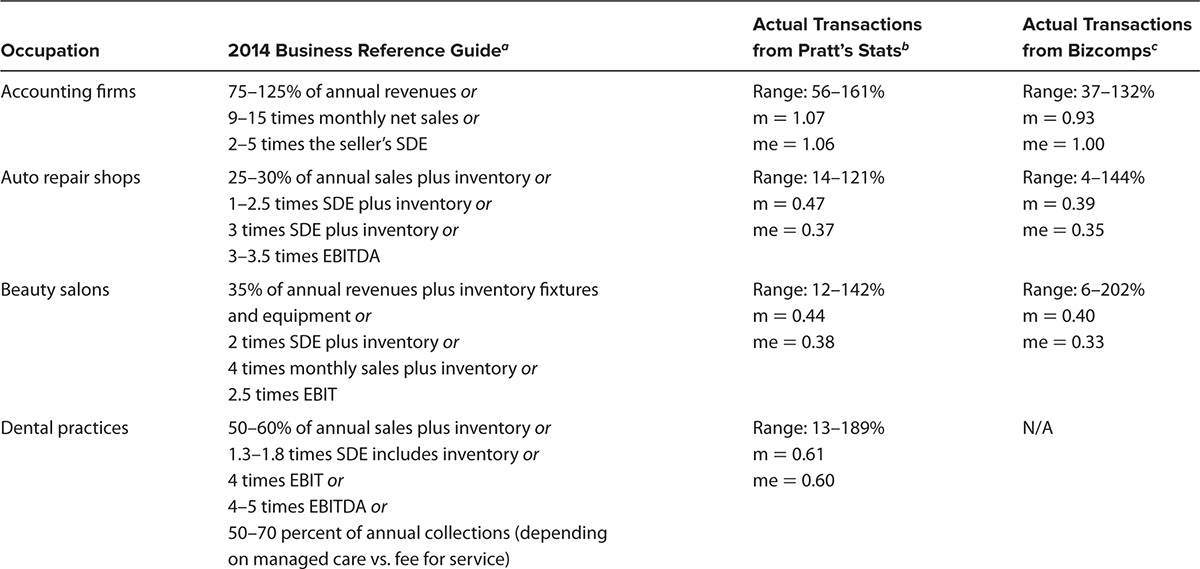

Tom West’s The Business Reference Guide includes an entire section on rules of thumb. Some of these rules of thumb, which are stated in terms of multiples of revenue, are shown in Exhibit 18.1. However, West also includes rules based on other parameters, particularly multiples of discretionary earnings (see Chapter 16 on the market approach).

Another source of rules of thumb is 101 + Practical Solutions for the Family Lawyer, in which Harriet Cohen presents rules of thumb for valuing several types of businesses and professional practices.3

If one wants to check an alleged rule of thumb against actual transactions, there are three databases that report ratios of price to discretionary earnings, as well as price to revenues, for actual completed sales of businesses. These are Bizcomps, the IBA Market Database, and Pratt’s Stats. The last named also indicates whether a covenant not to compete or an employment agreement was involved, and if so, how much value was allocated to it. These databases are listed in the references at the end of the chapter.

Exhibit 18.1 includes data on multiples of revenue derived from actual transactions from the Pratt’s Stats and Bizcomps databases. As can be seen from the exhibit, the actual multiples diverge quite a bit from the rules of thumb, proving that rules of thumb are not very reliable.

Rules of Thumb for Valuation

It is important to recognize that these rules of thumb and the transaction prices shown in both Pratt’s Stats and Bizcomps represent face values of transactions, not cash equivalent values. They usually include below-market seller financing and often include future payments that are contingent on future performance, such as retention of existing customers. Perhaps more important, the prices usually include values of noncompete covenants and employment agreements, that may or may not be considered part of the marital estate.

If the data are to be used for marital property settlements, we highly recommend that the parties’ experts go to the actual transaction data now widely available to derive multiples based on recent transactions and to recompute the ratios after eliminating noncompete and employment agreements in jurisdictions where those agreements would not be considered marital property.

Also, most rules of thumb reflect the assumption that the seller will stay with the business for some period of time to assist in the transaction. To this extent, they implicitly imply some personal goodwill. There is a trend among states to separate personal from enterprise goodwill and to exclude personal goodwill from the marital estate.

Courts generally have been inclined to reject valuation opinions based on rules of thumb. One opinion, for example, contained the following language:

[These] formulas … “are in reality the starting point of negotiation; and should not be confused with a valuation procedure.” … Formulas based on gross billings are usually converted to a time payout of the purchase price and, as such, can be misleading because they are often negotiated more over the terms of payment than over the actual value of the business being acquired. … While “rules of thumb may be helpful to accountants or business people to gauge the overall fairness of a particular transaction,” that is, whether it is “in the ballpark,” they are not at all helpful to the Court in fixing a specific value on a specific economic enterprise in an ancillary proceeding. … A rule of thumb by definition provides no theory. At best it is a guide or points out direction. At worst, it is nothing.4

However, rules of thumb have been accepted by courts in one form or another. In one case, the husband’s expert simply utilized a rule-of-thumb multiplier of three to five times the husband’s salary, then subtracted corporate debt to reach a final value. The trial court adopted this figure as opposed to the asset-based valuation presented by the wife’s expert. The decision was appealed and upheld.5

Cohen, Harriet N. 2003. “Using Rules of Thumb in Valuation.” In 101 + Practical Solutions for the Family Lawyer, 2nd ed., edited by Gregg Herman. Chicago: American Bar Association.

Desmond, Glenn M. 1993. Handbook of Small Business Valuation Formulas and Rules of Thumb, 3d ed., Valuation Press.

Feder, ed. 1997. “Courts’ Use of Rules of Thumb to Value Assets.” In Valuation Strategies in Divorce, 4th ed. pp. 450–453.

Fishman, Jay, et al. 2015. “Rules of Thumb” and “The Problem with Rules of Thumb in the Valuation of Closely-Held Entities.” In PPC’s Guide to Business Valuations. Practitioners Publishing, Fort Worth, TX pp. 7-40, 7-51 to 7-53.

Pratt, Shannon P., and Alina V. Niculita. 2007. “Formulas or Rules of Thumb.” In Valuing a Business, 5th ed. McGraw-Hill, New York, pp. 319–320.

West, Tom. “Rules of Thumb.” In The Business Reference Guide 2014, 24th ed. Business Brokerage Press, Westford, MA,

Note: The following databases can be accessed through BVResources.com.

Asset Business Appraisal

Post Office Box 97757

Las Vegas, NV 89193

(858) 457-0366

IBA Market Database

Institute of Business Appraisers

Post Office Box 17410

Plantation, FL 33318

(954) 584-1144

Pratt’s Stats

Business Valuation Resources

1000 SW Broadway, Suite 1200

Portland, OR 97205

(888) 287-8258