Chapter 8

Neurotransmitter Receptors

Chemical synaptic transmission plays a fundamental role in neuron-to-neuron and neuron-to-muscle communication and is mediated by receptors embedded in the plasma membrane. The cellular response is determined by which specific receptor(s) the transmitter binds, and the response can be either excitatory or inhibitory. This important feature of chemical synaptic transmission is termed sign inversion because excitation of one neuron in the circuit can cause inhibition of the follower neuron. The response magnitude is ultimately determined by receptor number, the “state” of the receptors, and the amount of transmitter released. Finally, the temporal and spatial summation of information conveyed by the activation of multiple receptors is the determinant of whether that neuron will fire an action potential or the muscle will contract. As one can see, there is remarkable flexibility and diversity in molding the response to neurotransmitter by constructing a synapse with the desired receptor types.

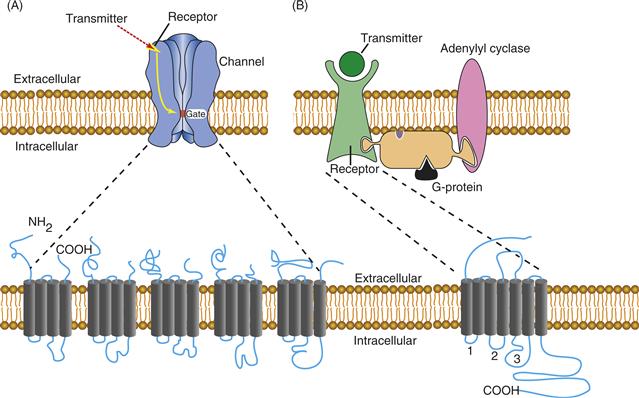

Two broad classifications exist for receptors: ionotropic and G-protein coupled (GPCR). An ionotropic receptor is a relatively large, multisubunit complex typically composed of four or five individual proteins that combine to form an ion channel through the membrane (Fig. 8.1A). In the absence of neurotransmitter, these ion channels exist in a closed state and are largely impermeable to ions. Neurotransmitter binding induces rapid conformational changes that open the channel, permitting ions to flow down their electrochemical gradients. Changes in membrane current resulting from ligand binding to ionotropic receptors generally are measured on a millisecond time scale. The ion flow ceases when the transmitter dissociates from the receptor or when the receptor becomes desensitized. In contrast, a GPCR is typically composed of a single polypeptide (Fig. 8.1B), although dimeric forms exist, and exerts its effects not through the direct opening of an ion channel but through binding to and activating GTP-binding proteins (G-proteins). Transmitters that activate GPCRs typically produce responses of slower onset and longer duration (from tenths of seconds to potentially hours) due to the series of enzymatic steps involved. However, faster responses can occur through actions of activated G-proteins, or their associated subunits, directly on ion channels.

Figure 8.1 A comparison of the general structural features of ionotropic and G-protein couples receptors. (A) Ionotropic receptors bind transmitter, and this binding translates directly into the opening of the ion channel through a series of conformational changes. Ionotropic receptors are composed of multiple subunits. The five subunits that together form the functional nAChR are shown. Note that each of the nAChR subunits wraps back and forth through the membrane four times and that the mature receptor is composed of five subunits. (B) G-protein coupled receptors bind transmitter and, through a series of conformational changes, bind to G-proteins and activate them. G-proteins then activate enzymes such as adenylyl cyclase to produce cAMP. Through the activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase, ion channels become phosphorylated, which affects their gating properties. GPCRs are single subunits or dimers. They contain seven transmembrane-spanning segments, with the cytoplasmic loops formed between the segments providing the points of interactions for coupling to G-proteins.

Ionotropic Receptors

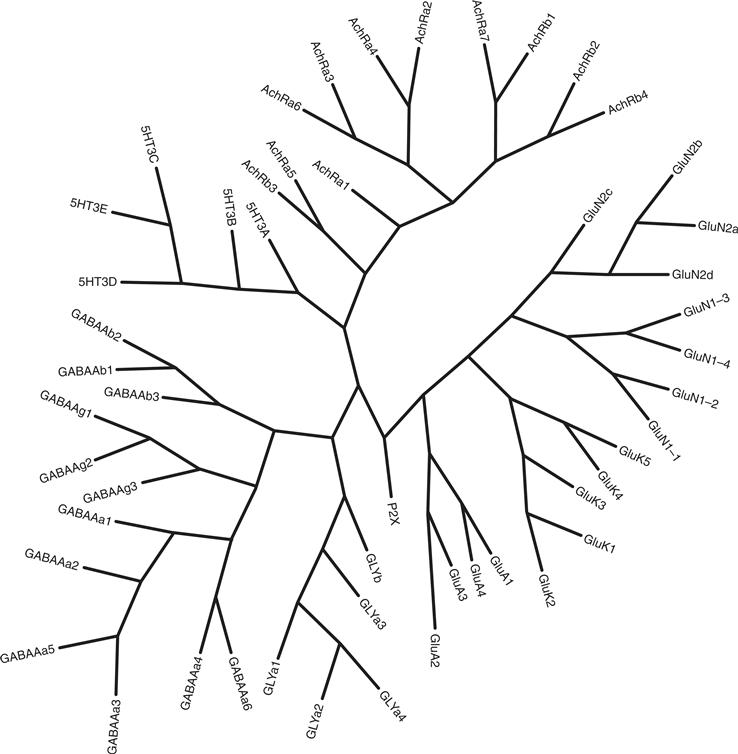

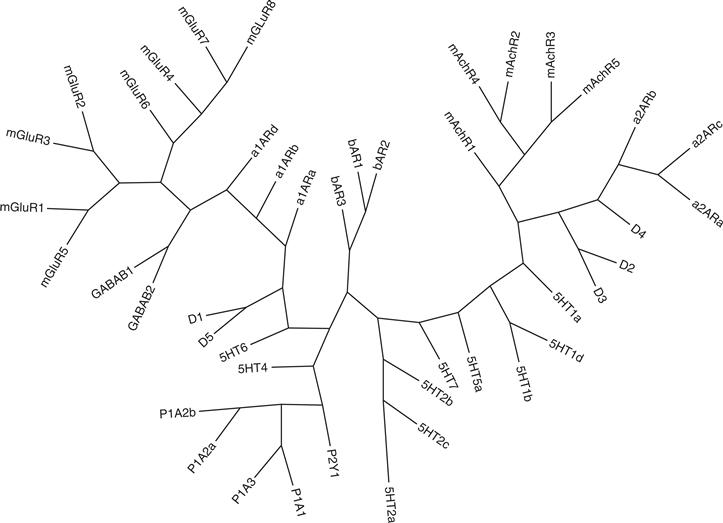

All ionotropic receptors are membrane-bound protein complexes that form an ion-permeable pore in the membrane. By comparing the amino acid sequence of cloned ionotropic receptors, one can deduce that they are similar in overall structure, although two independent ancestral genes gave rise to two distinct families (Fig. 8.2). One family includes the nicotinic acetylcholine (Ach) receptor (nAChR), the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor (GABAA), the glycine receptor, and one subclass of serotonin (5-HT) receptor, the 5HT3 receptor. The other family comprises the set of ionotropic glutamate receptors (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994; Traynelis et al., 2010).

Figure 8.2 Evolutionary relationships of the ionotropic receptor family. The tree was constructed by aligning the protein sequences from each receptor family with the ClustalW program. Based on the alignment, the phylogenetic relationship was inferred with the maximum parsimony method and the tree was constructed using the Phylogeny Inference Package v 3.6 (distributed by J. Felsenstein, Department of Genome Sciences, University of Washington, Seattle, WA). Dr. Yin Liu (Department of Neurobiology and Anatomy, University of Texas Health Science Center-Houston, Houston, TX) kindly provided the phylogenetic tree and figure.

The nAChR is a Heteromeric Protein Complex with Distinct Architecture

The nAChR is so named because the plant alkaloid nicotine can bind to the ACh-binding site and activate the receptor. The nAChR purified from the electric organ of Torpedo ray is composed of five subunits (Fig. 8.1A) and has a native molecular mass of approximately 290 kDa. The subunits are designated α, β, γ, and δ, and each receptor complex contains two copies of the α subunit. The subunits are homologous membrane-bound proteins that assemble in the bilayer to form a ring enclosing a central pore. The extracellular domain of each subunit together forms a funnel-shaped opening that extends approximately 100 Å outward from the outer leaflet of the plasma membrane. The funnel at the outer portion of the receptor has an inside diameter of 20–25 Å. The funnel shape is thought to concentrate and force ions to interact with amino acids in the limited space of the pore without producing a major barrier to diffusion. This funnel narrows near the center of the lipid bilayer to form the domain of the receptor that determines the opened or closed state of the ion pore (Fig. 8.1). The intracellular domain of the receptor forms short exits for ions traveling into the cell and an entrance for ions traveling out of the cell. The intracellular domain also establishes the association of the receptor with other intracellular proteins that determine the subcellular localization of the nAChR.

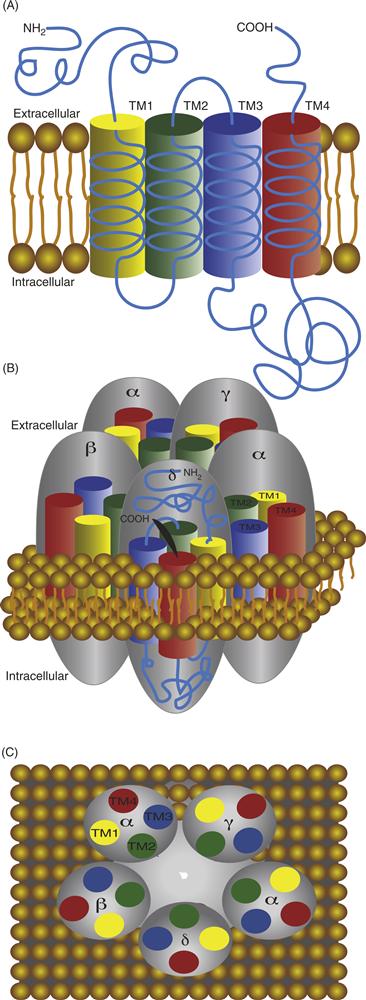

Each nAChR Subunit Has Multiple Membrane-Spanning Segments

The primary structure of each nAChR subunit was obtained by the efforts of Shosaka Numa and colleagues. The deduced amino acid sequence from cloned mRNAs indicates that nAChR subunits range in size from 40 to 65 kDa. Each subunit consists of four transmembrane (TM)-spanning segments referred to as TM1–TM4 (Fig. 8.3A). Each segment is composed mainly of hydrophobic amino acids that stabilize the domain within the hydrophobic environment of the lipid membrane. The four TM domains are arranged in an antiparallel fashion, wrapping back and forth through the membrane. The N terminus of each subunit extends into the extracellular space, as does the loop connecting TM2 and TM3, as well as the C terminus (Fig. 8.3A). Amino acids linking TM1 and TM2 and those linking TM3 and TM4 form short loops that extend into the cytoplasm.

Figure 8.3 (A) Diagram highlighting the orientation of membrane-spanning segments of one subunit of the nAChR. The amino and carboxy termini extend in the extracellular space. The four membrane-spanning segments are designated TM1–TM4. Each forms an α helix as it traverses the membrane. (B) Side view of the five subunits in their approximate positions within the receptor complex. There are two α subunits present in each nAChR. (C) Top view of all five subunits highlighting the relative positions of their membrane-spanning segments, TM1–TM4, and the position of TM2 that lines the channel pore.

Structure of the Channel Pore Determines Ion Selectivity and Current Flow

In the model shown in Figure 8.3B and 8.3C, each subunit of the nAChR can be seen to contribute one cylindrical component (representing a membrane-spanning segment) that presents itself to a central cavity that forms the ion channel through the center of the complex. The membrane-spanning segments that line the pore are the five TM2 regions, one contributed by each subunit. The amino acids that compose the TM2 segment are arranged in such a way that three rings of negatively charged amino acids are oriented toward the central pore of the channel (Fig. 8.3A). These rings of negative charge appear to contribute to the selectivity filter of the channel, increasing the probability that only cations can pass through the pore. The nAChR is permeable to most cations, such as Na+, K+, and Ca2+, although monovalent cations are preferred. The restricted physical dimensions of the pore—9–10 Å in the open state—contribute greatly to the selectivity for particular ions (Unwin, 1995, 2005). A coarse filtering that also influences selectivity appears to be a shielding effect produced by other negatively charged amino acids surrounding the outer channel region of the receptor. Collectively, these physical characteristics of the pore—together with the electrochemical gradient across the plasma membrane—determine the possibility and rate of ion movements. Thus, when the pore of the nAChR opens, anions are restricted from movement across the membrane, while positively charged cations move down their respective electrochemical gradients, resulting in an influx of Na+ and Ca2+ and a small efflux of K+.

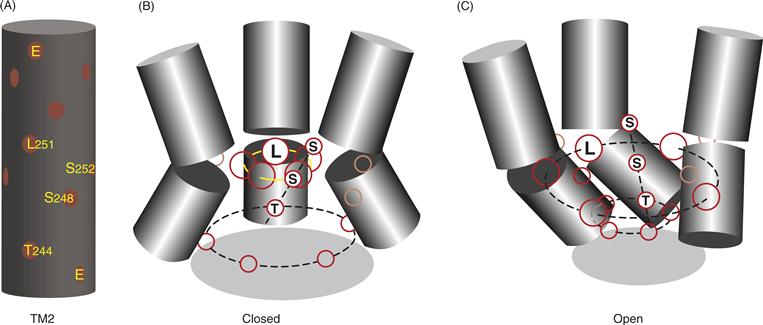

Opening of the nAChR Occurs through Concerted Conformational Changes Induced by Binding of Two ACh Molecules

Each receptor complex has two ACh-binding sites that reside in the extracellular domain and are formed for the most part by six amino acids in α subunits; however, amino acids in both γ and δ subunits also contribute to binding. The two binding sites are not equivalent because of the asymmetry of the receptor produced by the different neighboring subunits (either γ or δ) adjacent to the α subunits. Significant cooperativity also exists within the receptor molecule, and so binding of the first molecule of ACh enhances binding of the second. When nAChR binds two molecules of ACh, the channel opens almost instantaneously (time constants for opening are approximately 20 μs), thus permitting the passage of ions. A model developed from electron micrographic reconstructions of the nicotine-bound form of the nAChR indicates that the closed-to-open transition is associated with a rotation of the TM2 segments (Fig. 8.4; Unwin, 1995, 2005). The TM2 segments are helical and exhibit a kink in their structure that forces a Leu residue from each segment into a tight ring that effectively blocks the flow of ions through the central pore of the receptor. When the TM2 segments rotate because of ACh binding, the kinks also rotate, relaxing the constriction formed by the Leu ring, and ions can then permeate through the pore. The rotation also orients a series of Ser and Thr residues (amino acids with a polar character) into the central area of the pore (compare Figs. 8.4B to 8.4C), which facilitates the permeation of water-solvated cations.

Figure 8.4 (A) Relative positions of amino acids in the TM2 segment of one of the nAChR a subunits modeled as an a helix. Glutamate residues (E) that form parts of the negatively charged rings for ion selectivity are shown at the top and bottom of the helix. (B) Arrangement of three of the five TM2 segments of the nAChR modeled with the receptor in the closed (ACh-free) configuration. In the closed configuration, leucine (L) residues form a right ring in the center of the pore that blocks ion permeation. (C) Arrangement of the three TM2 segments after ACh binds to the receptor. In the open configuration, construction formed by the ring of leucine (L) residues opens as the helices twist about their axes. Note that polar serine (S) and threonine (T) residues align when ACh binds, which apparently help the water-solvated ions travel though the pore.

Adapted from Unwin (1995).

The Muscle Form of the nAChR is Very Similar to the nAChR from Torpedo

nAChRs at the neuromuscular junction are a concentrated collection of homogeneous receptors having a structure similar to that of the Torpedo electric organ. This similarity is not surprising because the electric organ is a specialized form of muscle tissue. The adult form of the muscle receptor has the pentameric structure α2βεδ and is highly similar in structure to the nAChR from Torpedo. An embryonic form of the muscle receptor has an analogous structure, except that the ε subunit is replaced by a unique γ subunit. The embryonic and adult subunits of both mouse and bovine muscle receptors have been cloned and expressed and the receptors differ in both channel kinetics and channel conductance. These differences in channel properties that occur due to subunit swapping appear to be necessary for the proper function of the nAChRs during the transition from developing to mature neuromuscular junction synapses.

The nAChR Has Well-Ordered Assembly, is Post-translationally Modified, and is Concentrated and Anchored in the Postsynaptic Membrane

The pathway of nAChR assembly in muscle is a tightly regulated process. The five subunits of the nAChR have the potential to assemble randomly into 208 different combinations. Nevertheless, in vertebrate muscle, only one of these configurations (α2βεδ) is typically found in mature tissue, indicating a very high degree of coordinated assembly and, ultimately, little structural variability. The well-ordered assembly takes place within the endoplasmic reticulum, and during intracellular maturation, each subunit is glycosylated. Two highly conserved disulfide bonds in the N-terminal extracellular domain are essential for efficient assembly of the mature receptor. The first is between two adjacent Cys residues that reside very close to the ACh-binding site on the receptor. The second bond is between two Cys residues 15 amino acids apart, forming a loop that is spatially adjacent to the TM domains of the native receptor. This “Cys loop” is a structural signature of this family of receptors and is also found in the GABAA receptor, the glycine receptor, the 5HT3 receptor, and two members of the purinergic receptors.

Many ionotropic receptors, such as the nAChR, are phosphorylated, although the functional significance of the phosphorylation is not always evident. The nAChR is phosphorylated by at least three protein kinases. cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) phosphorylates the γ and δ subunits, Ca2+/phospholipid-dependent protein kinase (PKC) phosphorylates the δ subunit, and an unidentified tyrosine kinase phosphorylates the β, γ, and δ subunits. The phosphorylation sites are all found in the intracellular loop between TM3 and TM4 membrane-spanning segments. Phosphorylation by these three protein kinases increases the rate of desensitization of the receptor. Desensitization of receptors is common, and this process limits the amount of ion flux through a receptor by producing transitions into a closed state (one that does not permit ion flow) in the continued presence of neurotransmitter. For the nAChR, the rate of desensitization has a time constant of approximately 50–100 ms.

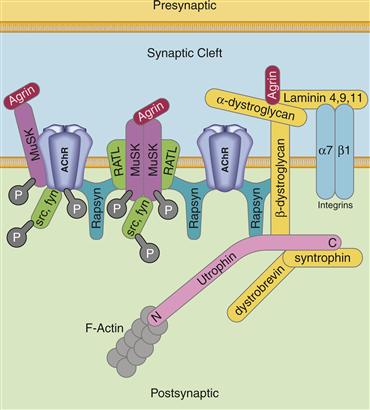

nAChRs are highly concentrated at the neuromuscular junction that ensures rapid and reliable communication between the presynaptic motor neuron and postsynaptic muscle cell to induce contraction (Fig. 8.5). The clustering of nAChRs begins during development, and is mediated in part by the release of agrin from the motor neuron that binds to a tyrosine kinase in the postsynaptic membrane called MuSK (Willmann & Fuhrer, 2002). MuSK activation recruits members of the Src family of kinases that phosphorylates the nAChR, leading to increased interactions with a multitude of postsynaptic signaling complexes ultimately leading to the recruitment of rapsyn. Rapsyn is a multidomain protein that binds directly to cytoplasmic tails of the nAChR subunits along with other proteins, including itself. Rapsyn thus forms the critical scaffolding function that clusters nAChRs at the NMJ. In addition to the nAChR, rapsyn binds to other important muscle proteins including MuSK and the dystrophin/utrophin glycoprotein complex (dystrophin is the molecule that when mutated leads to certain types of muscular dystrophy). Activity of the nAChR itself is also critical for its stabilization at the neuromuscular junction. For example, the lifetime of the nAChR at the junction decreases from 14 d to less than a day following block of the receptor with α-bungarotoxin. The interplay of signals coming from the presynaptic motor neuron is integrated by the postsynaptic receptors to concentrate and stabilize AChRs at the neuromuscular junction.

Figure 8.5 Diagram of nAChR clustering at the neuromuscular junction. Rapysn is a major anchoring protein at the neuromuscular junction that binds to itself and to the nAChR that concentrates and stabilizes nAChRs. The development and stabilization of the neuromuscular junction is mediated by a number of signaling cascades, only a few of which are shown. For example, agrin released from the presynaptic motor neuron binds to a number of proteins associated with the postsynaptic membrane including the tyrosine kinase MuSK (muscle specific kinase). MuSK activation by agrin recruits and activates the soluble tyrosine kinases src and fyn that further modify a number of proteins. RATL (rapsyn associated linker protein) is a membrane-bound protein that binds to both MuSK and to rapsyn to anchor MuSK at the neuromuscular junction. Agrin also interacts with the dystroglycans that make up the dystrophin complex important for the maintenance of the neuromuscular junction. Rapsyn also binds to the utrophin complex that anchors the overlying protein complex to the actin cytoskeleton.

Adapted from Willmann and Fuhrer (2002).

Neuronal nAChRs Contain Two Types of Subunits and Their Assembly Leads to Functional Diversity

Neuronal nAChRs are similar yet distinct in structure to the Torpedo isoform of the receptor. For example, the neuronal nAChR is composed of only two types of subunits, α and β, which combine to produce the functional receptor, and the majority of these receptors do not bind to α-bungarotoxin. At least ten different α subtypes (α1 being the muscle α subunit) have been identified (see Fig. 8.2 for comparisons), and some are species-specific (α8 is found only in chicken and α9 is found only in rat). Four different β subtypes (β1 being the muscle β subunit) have been identified. The neuronal β subunits are distantly related to the muscle β1 subunit and sometimes are referred to simply as non-α subunits. All the α and β genes encode proteins with four transmembrane-spanning segments, and although the physical structure of this receptor family has not been well characterized, it appears that each functional receptor is a pentameric assembly.

Neuronal nAChRs have diverse functions and are the receptors presumed to be responsible for the psychophysical effects of nicotine addiction. One major function of nAChRs in the brain is to modulate excitatory synaptic transmission through a presynaptic action. The diversity in function of nAChRs can be related to the heterogeneous structure contributed by the thousands of possible combinations between the different α and β subunits. Functional neuronal nAChRs can be assembled from a single subunit (e.g., α7, α8, or α9), or a single type of α subunit can be assembled with multiple types of β subunits (e.g., α3 with β2 or β4 or both) and vice versa. The mammalian high affinity nicotine-binding receptor appears to be formed by the α4 and β2 subunits. These subunit-mixing possibilities produce a staggering array of potential receptor molecules, each with distinct properties, including differences in single-channel kinetics and rates of desensitization. It is also now established that subunit composition plays important roles in targeting the receptors to different intracellular locations.

Neuronal nAChRs exhibit a range of single-channel conductance between 5 and 50 pS, depending on the tissue or the specific subunits expressed. All the neuronal nAChRs are cation-permeable channels that, in addition to permitting the influx of Na+ and the efflux of K+, permit an influx of Ca2+. The Ca2+ permeability for neuronal nAChR is greater than that for the muscle nAChR and is variable among the different neuronal receptor subtypes. Indeed, some receptors have very high Ca2+/Na+ permeability ratios; for example, α7 nAChRs exhibit a Ca2+/Na+ permeability ratio of nearly 20, whereas other neuronal isoforms exhibit Ca2+/Na+ permeability ratios of about 1.0–1.5. The Ca2+ permeability of the α7 nAChR can be eliminated by the mutation of a single amino acid residue in TM2 (Glu-237 for Ala) without significantly affecting other aspects of the receptor. This key Glu residue presumably lies at a critical position within the pore of the receptor and enhances the passage of Ca2+ ions through an interaction with its negatively charged side chain. Activation of α7 receptors through the binding of ACh therefore could produce a significant increase in the level of intracellular Ca2+ without the opening of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Subunits α7, α8, and α9 are also the α-bungarotoxin-binding subtypes of neuronal nAChRs.

For the nAChR from muscle, desensitization is minor and probably is not of physiological significance in determining the shape of the synaptic response at the neuromuscular junction. However, for some neuronal nAChRs, desensitization plays a major role in determining the effects of the actions of ACh. Receptors composed of α7, α8, and certain α/β combinations exhibit desensitization time constants of between 100 and 500 ms, whereas others exhibit desensitization constants between 2 and 20 s. Rapid desensitization eliminates that receptor from contributing to synaptic responses until the process is reversed. Given the diverse functions of neuronal nAChRs, the variable rates of desensitization likely play important roles whereby this inherent property of the receptor shapes the physiological response generated from binding ACh.

One Serotonin Receptor Subtype, 5-HT3, is Ionotropic and is a Close Relative of the nAChR

5-HT historically is thought to activate GPCRs (described in more detail later). The 5-HT3 subclass is an exception forming an ionotropic receptor activated by binding 5-HT. 5-HT3 receptors are distributed sparsely on primary sensory nerve endings in the periphery and are also distributed widely in the mammalian CNS. The 5-HT3 receptor is clinically significant because antagonists of 5-HT3 receptors have important applications as antiemetics, anxiolytics, and antipsychotics.

The 5-HT3 receptor is permeable to Na+ and K+ ions and is similar in many ways to the nAChR (see evolutionary tree; Fig 8.2) in that both desensitize rapidly and are blocked by tubocurarine. The 5-HT3 receptor is a homomeric complex composed of five copies of the same subunit. Each protein subunit is 487 amino acids long (56 kDa) and has a structure most analogous to the α7 subtype of neuronal nAChRs, which also forms a homooligomeric receptor. The 5-HT3 receptor is mostly impermeable to divalent cations. For example, Ca2+ is largely excluded from permeation and in fact effectively blocks current flow through the pore, even though the pore size of the channel (7.6 Å) is approximately the same as that for the nAChR (8.4 Å). Apparently, other physical or electrochemical barriers limit the capacity of divalent ions to permeate the 5-HT3 pore. Dose–response studies indicate that at least two ligand-binding sites must be occupied for the channel to open; however, the binding of agonist and/or opening of the channel appears to be approximately 10 times slower than for most other ligand-gated ion channels. The functional significance or physical explanation of this slow opening is not known. The native 5-HT3 receptor also exhibits desensitization (time constant 1–5 s), although the reported desensitization rate varies widely, depending on the methodology used for analysis and the source of receptor. Interestingly, this desensitization can be significantly slowed or enhanced by single amino acid substitutions at a Leu residue in the TM2 segment of the subunit.

GABAA Receptors Are Related in Structure to nAChRs but Exhibit an Inhibitory Function

Synaptic inhibition in the mammalian brain is mediated principally by GABA receptors. The most widespread ionotropic receptor activated by GABA is designated GABAA. The subunits composing the GABAA receptor have sequence homology with the nAChR subunit family, and the two families have presumably diverged from a common ancestral gene. The evolutionary relationship of these two receptor families can be appreciated in Fig. 8.2. The GABAA receptor is composed of multiple subunits, forming a heteropentameric complex of approximately 275 kDa. Seven different types of subunits are associated with GABAA receptors and are designated α, β, γ, δ, ε, π and θ. An additional subunit, ρ, is found predominantly in the retina, whereas the other subunits are distributed widely in the brain. Each subunit group also has different subtypes (see Fig 8.2); for example, six different α, three β, three γ, and two other ρ subunits have also been identified. The predicted amino acid sequences indicate that each of these subunits has a molecular mass ranging between 48 and 64 kDa. Like neuronal nAChR, these subunits mix in a heterogeneous fashion to produce a wide array of GABAA receptors with different pharmacological and electrophysiological properties. The predominant GABAA receptor in brain and spinal cord is α1, β2, and γ2, with a stoichiometry of two α1s, two β2s, and one γ2. Expression of subunit cDNAs in oocytes indicates that the α subunit is essential for producing a functional channel. The α subunit also appears to contain the high-affinity binding site for GABA.

The ion channel associated with the GABAA receptor is selective for the anion Cl-, and the selectivity is provided by amino acid residues strategically positioned in the TM2 near the ends of the pore. When GABA binds to and activates this receptor, Cl- flows into the cell, producing a hyperpolarization by moving the membrane potential away from the threshold for firing an action potential. The neuronal GABAA receptor exhibits multiple conductance levels, with the predominant conductance being 27–30 pS.

The GABAA Receptor Binds Drugs That Affect Its Properties

The GABAA receptor is an allosteric protein and the binding of a number of compounds modulates its properties. Two well-studied examples are barbiturates and benzodiazepines, both of which bind to the GABAA receptor and potentiate GABA binding, although they do this by binding to distinct sites. Benzodiazepines produce effects by increasing the frequency of channel opening, while barbiturates prolong channel burst durations. The net result is that in the presence of barbiturates, benzodiazepines, or both, the same concentration of GABA will cause increased inhibition by increasing the amount of Cl- influx leading to increased hyperpolarization. Benzodiazepine binding is conferred on the receptor by the γ subunit, but the presence of α and β subunits is necessary for the qualitative and quantitative aspects of benzodiazepine binding. The benzodiazepine-binding site appears to lie along the interface between α and γ subunits and only certain subtypes are sensitive to benzodiazepines. Benzodiazepine binding to GABAA receptors requires α2 or α5 and γ2 or γ3; other subunit combinations are insensitive to benzodiazepines.

Picrotoxin, a potent convulsant compound, binds within the channel pore of the GABAA receptor and prevents ion flow. Single-channel experiments indicate that picrotoxin either slowly blocks an open channel or prevents the GABA receptor from undergoing a transition into a long-duration open state. Apparently, barbiturates produce similar changes in channel properties, but they potentiate rather than inhibit GABAA receptor function. Bicuculline, another potent convulsant, appears to inhibit GABAA receptor channel activity by decreasing the binding of GABA to the receptor. Steroid metabolites of progesterone, corticosterone, and testosterone also have potentiating effects on GABA currents that are similar in many ways to the action of barbiturates; however, the binding sites for steroids and barbiturates are distinct. Finally, penicillin directly inhibits GABA receptor function, apparently by binding within the pore.

The physiological effects of compounds such as picrotoxin, bicuculline, and penicillin are striking. Each of these compounds at a sufficiently high concentration can produce widespread and sustained seizure activity. Conversely, many, but not all, of the sedative properties associated with barbiturates and benzodiazepines can be attributed to their ability to augment inhibition in the brain through enhancing the inhibitory potency of GABA.

Interestingly, ρ-subunit-containing GABA receptors, found in abundance in the retina, are pharmacologically unique. They are resistant to the inhibitory action of bicuculline, although they remain sensitive to blockage by picrotoxin. In addition, these retinal receptors are not sensitive to modulation by barbiturates or benzodiazepines. Thus, ρ-containing receptors are distinct from GABAA receptors and are similar to receptors earlier designated GABAC.

The Glycine Receptor is Closely Related to the GABAA Receptor

Glycine receptors are the major inhibitory receptors in the spinal cord and the brain stem. Glycine receptors are similar to GABAA receptors in that both are ion channels selectively permeable to the anion Cl-. As one would anticipate, they both lie on the same main branch of the evolutionary tree of ionotropic receptors (Fig. 8.2) Interestingly, only three amino acid replacements in the TM1-TM2 loop and the TM2 segment can change the selectivity of the glycine receptor from anionic to cationic, pointing again to the critical nature of residues in the TM2 segment in determining a receptor’s ion selectivity. The overall structure of the glycine receptor is indicative of this similarity in properties. The native complex is approximately 250 kDa and is composed of two main subunits: α (48 kDa) and β (58 kDa). The receptor appears to be pentameric, most likely composed of three α and two β subunits. The glycine receptor has an open channel conductance of approximately 35–50 pS, similar to that of the GABAA receptor. The rat poison strychnine is a potent antagonist of the glycine receptor.

Four distinct α subunits and one β subunit of the glycine receptor have been cloned and are highly related (Fig. 8.2). Each exhibits the typical predicted four TMs and is approximately 50% identical to the others at the amino acid level. Expression of a single α subunit in oocytes is sufficient to produce functional glycine receptors, indicating that the α subunit is the pore-forming unit of the native receptor. β subunits play exclusively modulatory roles, affecting, for example, sensitivity to the inhibitory actions of picrotoxin. They are widespread in the brain but not always found in neurons expressing α subunits, suggesting β subunits may serve other functions independent of their association with glycine receptors.

The GABAA and Glycine Receptor Cluster at Synapses

During maturation of inhibitory synapses, gephyrin is found beneath the postsynaptic membrane and recruits and localizes GABAA or glycine receptors. Gephyrin appears to serve an analogous function for the stabilization of inhibitory receptors that rapsyn plays for nAChRs (Fig 8.5). Gephyrin is a multidomain protein that interacts with the cytoplasmic domains of the GABAA or glycine receptor subunits. Like rapsyn, gephyrin interacts with itself and other proteins in addition to the inhibitory receptors and these interactions serve to restrict the lateral mobility of GABAA and glycine receptors in the plasma membrane. Ultimately these interactions promote the formation of postsynaptic inhibitory specializations.

Certain Purinergic Receptors Are Also Ionotropic

Purinergic chemical transmission is distributed throughout the body and is considered in greater detail in a later section on GPCRs. Purinergic receptors bind to ATP (or other nucleotide analogs) or its breakdown product adenosine (Junger, 2011). ATP is released from certain synaptic terminals in a quantal manner and often is packaged within synaptic vesicles containing another neurotransmitter, the best described being ACh and catecholamines.

One class of ATP-binding purinergic receptors (P2X) has been discovered to be ionotropic, and there are at least seven members of this class (P2X1–P2X7). Note that the P2X receptors reside between the GABA/glycine and the glutamate family of ionotropic receptors on the evolutionary tree (Fig. 8.2). P2X receptors most often mediate a fast depolarizing response in neurons and muscle cells in response to ATP or other nucleotides by the direct opening of relatively nonselective cation channels. cDNAs encoding the P2X receptor indicate that its structure comprises only two transmembrane domains, with some homology in its pore-forming region with K+ channels and the functional receptors seemed to be composed of three subunits in contrast to five for the nAChR. The P2X7 receptor is also a ligand-gated channel that permits permeation of either anions or cations and even molecules as large as 900 Da in the presence of high (millimolar) nucleotide levels.

Glutamate Receptors Are Derived from a Different Ancestral Gene and Are Structurally Distinct from Other Ionotropic Receptors

Glutamate receptors are widespread in the nervous system, where they are responsible for mediating the vast majority of excitatory synaptic transmission in the brain and spinal cord. Four agonists serve to distinguish different types of glutamate receptors; N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA), amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazoleproprionic acid (AMPA), kainate, and quisqualate (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994; Watkins, Krogsgaard-Larsen, & Honore, 1990). A convenient distinction for describing ionotropic glutamate receptors has been to classify them as either NMDA or non-NMDA subtypes, depending on whether they bind the agonist NMDA. Non-NMDA receptors also bind the agonist kainite or AMPA. Both NMDA and non-NMDA receptors are ionotropic. Quisqualate is unique within this group of agonists in having the capacity to activate both ionotropic and GPCR glutamate receptor subtypes (mGluRs; Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994). The nomenclature describing members of the glutamate receptor family has undergone transitions over the years but appears to have converged; receptors binding AMPA are termed GluA1–GluA4; those binding kainate are GluK1–GluK5 and those binding NMDA are GluN1, GluN2A–GluN2D, and GluN3A–GluN3B; and those that activate G-proteins are designated mGluR1–mGluR8 (Traynelis et al., 2010). A family tree highlighting the evolutionary relationship of the glutamate receptors between themselves and other members of the ionotropic receptor family is shown in Figure 8.2.

Non-NMDA Receptors Are a Diverse Family

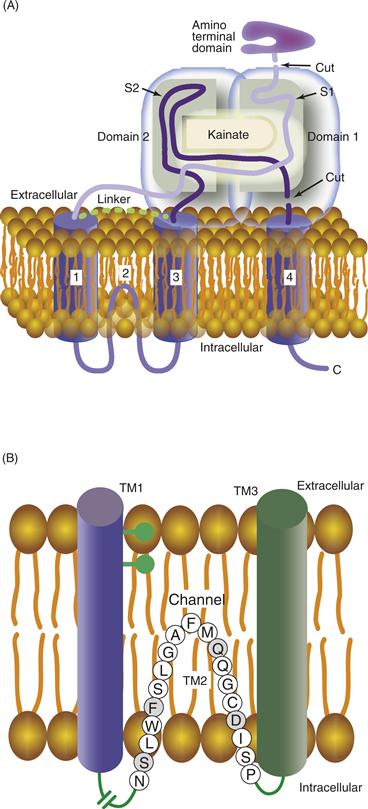

The initial glutamate receptor clone was termed GluR-K1, and the cDNA encoded a protein with an estimated molecular mass of 99.8 kDa (Hollmann, O’Shea-Greenfield, Rogers, & Heinemann, 1989). Not long after this original report, several groups (Boulter et al., 1990; Keinanen et al., 1990; Nakanishi, Shneider, & Axel, 1990) independently reported the isolation of families of glutamate receptor subunits, now termed GluA1–GluA4, GluK1–GluK5, and GluD1 and GluD2. Each GluR subunit consists of approximately 900 amino acids and has four predicted membrane-spanning segments (TM1–TM4); however, there is an important distinction in the TM2 domain, making the GluRs distinct from the nAChR family (Figs. 8.6A and 8.6B). Native GluRs are tetrameric, as opposed to the pentameric nAChR family of receptors, and have approximate molecular mass of 600 kDa making them almost twice the size of the nAChR, mostly because of the large extracellular domain where glutamate binds.

Figure 8.6 (A) Model of one of the subunits of the ionotropic glutamate receptor. Ionotropic glutamate receptors have four membrane-associated segments; however, unlike nAChR, only three of them completely traverse the lipid bilayer. TM2 forms a loop and exits back into the cytoplasm. This leaves the large N-terminal region extending into the extracellular space, whereas the C terminus extends into the cytoplasm. Two domains in the extracellular segments associate with each other to form the binding site for transmitter, in this example kainate, a naturally occurring agonist of glutamate. (B) Enlarged area of the predicted structure and amino acid sequence of the TM2 region of the glutamate receptor, GluR3. TM1 and TM3 are drawn as cylinders in the membrane flanking TM2. The residue that determines Ca2+ permeability of the non-NMDA receptor is the glutamine residue (Q) highlighted in gray. In NMDA receptors, an asparagine residue at this same position is the proposed site of interaction with Mg2+ ions that produce the voltage-dependent channel block. Serine (S) and phenylalanine (F), also shaded in gray, are highly conserved in the non-NMDA receptor family. The aspartate (D) residue is also conserved and is thought to form part of the internal cation-binding site. The break in the loop between TM1 and TM2 indicates a domain that varies in length among ionotropic glutamate receptors.

Adapted from Wo and Oswald (1995).

Unique Properties of Non-NMDA Receptors Are Determined by Assembly of Different Subunits

When cDNAs encoding these receptors were expressed in either oocytes or HeK-293 cells, application of the non-NMDA receptor agonist AMPA produced substantial inward currents. A striking observation from these expression studies was that when the GluA2 subunit was expressed alone, little stimulated current was obtained, unlike the large currents found when either GluA1 or GluA3 was expressed (Nakanishi et al., 1990; Verdoorn et al., 1991). GluA2 subunits by themselves appear to form poorly conducting receptors. However, when GluA2 is expressed with either GluA1 or GluA3, the behavior of the heteromeric receptor is distinctly different. When GluA1 and GluA3 are expressed alone or together, they produce channels with strong inward rectification. Coexpression of GluA2 with either GluA1 or GluA3 produces a channel with little rectification. Further analyses indicated that GluA1 and GluA3 expressed channels were permeable to Ca2+ (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994). In contrast, any combination of receptor that included the GluA2 subunit produced channels impermeable to Ca2+. The replacement of a single amino acid (Arg for Gln) in TM2 of the GluA2 subunit (see Fig. 8.6B for identification of this amino acid) was shown to control Ca2+-permeability (Burnashev et al., 1992). Apparently, an Arg at this position blocks Ca2+ from traversing the pore formed in the center of the GluR channel.

Functional Diversity in GluRs is Produced by mRNA Splicing and RNA Editing

Analysis of mRNAs encoding GluR subunits indicated that each could be expressed in one of two splice variants, termed flip and flop. These flip and flop modules are small segments (38 amino acids) just preceding the TM4 domain in all four GluA subunits. The receptor channel expressed from these splice variants has distinct properties, depending on which of the two modules is present. Specifically, flop-containing receptors desensitize more during glutamate application. Therefore, GluAs with flop modules express smaller steady-state currents than GluAs with flip modules. Both flip- and flop-containing GluAs are widely expressed in the brain with a few exceptions.

Typically, one finds that there is fidelity in the process of transcribing DNA into mRNA and then into protein—that is, that nucleotides present in the DNA are accurate predictors of the amino acid sequence of the translated protein. However, a novel mechanism in the neuronal nucleus was discovered that edits mRNAs post-transcriptionally, and at least three of the four GluA subunits are subjected to this process (Sommer, Kohler, Sprengel, & Seeburg, 1991). In fact, one of the sites edited is the critical Arg residue regulating Ca2+ permeability in the GluA2 subunit. At another edited site, Gly replaces Arg-764 in the GluA2 subunit, and this editing also takes place in GluA3 and GluA4. The Arg-to-Gly conversion at amino acid 764 produces receptors that exhibit significantly faster rates of recovery from the desensitized state. The extent to which other receptors or other protein molecules undergo this form of editing is an area rich for investigation. At a minimum, this editing mechanism produces dramatic differences in the function of GluRs.

Glutamate Receptors Do Not Conform to the Typical Four Transmembrane-Spanning Segment Structure Described for nAChRs

The field of glutamate receptor structure/function is advancing at a rapid pace fostered by the crystallization of the GluA2 receptor (Sobolevsky, Rosconi, & Gouaux, 2009) and report of the 3D structure of the native GluR determined by electron microscopy reconstructions (Nakagawa, Cheng, Ramm, Sheng, & Walz, 2005). These studies reveal the overall architecture of the tetrameric GluR complex and provide some global insights into how glutamate binding leads to channel opening. These models can be additionally refined by the significant amount of work analyzing crystal structures of the isolated GluR ligand-binding domain with and without the presence of bound agonists and antagonists (see Traynelis et al., 2010, for review).

The GluR has a large extracellular domain composed of the amino-terminal domain (ATD) important for receptor assembly and trafficking and the ligand-binding domain (LBD) that serves as the binding site for glutamate (Fig. 8.6A). These domains form a structurally unique dimer arrangement in the extracellular domain that transitions into a fourfold symmetry of the pore-forming region of the TM domains. Unlike the four TM segments of the nAChR that each completely traverses the membrane, the TM2 segment of GluRs forms a reentrant loop within the membrane (Fig. 8.6A) and enters back into the cytoplasm, similar in some ways to the pore-forming domain (P segment) of voltage-activated K+ channels. An enlargement of this TM2 segment (Fig. 8.6B) highlights the amino acids conserved in the GluRs and further shows the positions of the critical Gln residue responsible for Ca2+ permeability of the receptor. Thus, it appears that glutamate receptors are highly divergent from the nAChR receptor family.

Other Non-NMDA GluRs Have Less Well-Characterized Functions

GluK1-GluK5 forms a second non-NMDA receptor subfamily (Fig. 8.2) that is activated by the agonist kainate but whose contribution to producing functionally distinct receptors is less well understood (Traynelis et al., 2010). Their overall structure is similar to that of GluA1–4, and they exhibit about 40% sequence homology; however, their agonist-binding profile and their electrophysiological properties are distinct. GluK1–GluK2 can form either homo- or heterotetramers, but GluK4 and GluK5 require coexpression with one of the GluK1–Gluk3 family members. They are generally expressed at lower levels in the brain than the GluA1–4 subtypes (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994). GluK4 is expressed at significant concentrations in only two cell types: hippocampal CA3 and dentate granule cells. GluK5 exhibits distinct properties when combined with other GluR subunits. For example, coexpression of GluK2 and GluK5 produces functional receptors that respond to AMPA, although neither subunit itself responds to this agonist.

GluD1 and GluD2 receptors can form homotetrameric receptors, but do not seem to form heteromers with other GluRs. They are also resistant to activation by all known agonists capable of activating other members of the GluR family (Traynelis et al., 2010). Their physiological role remains poorly characterized.

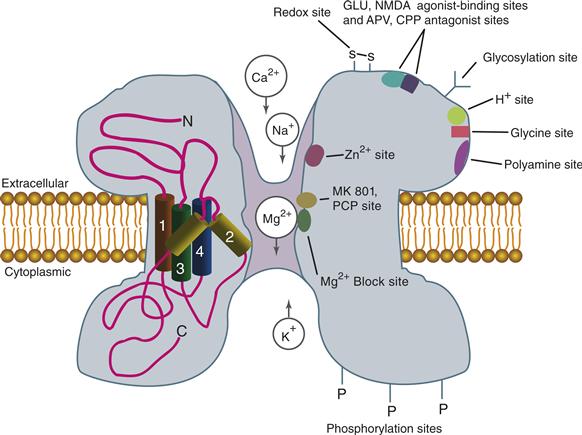

NMDA Receptors Are a Family of Ligand-Gated Ion Channels That Are Also Voltage Dependent

NMDA receptors are involved in aspects of development, learning and memory, and neuronal damage due to brain injury. The particular significance of this receptor to neuronal function comes from two of its unique properties. First, the receptor exhibits associativity. For the channel to be open, the receptor must bind glutamate and the membrane in which it resides must be depolarized. This behavior is due to an Mg2+-dependent block of the receptor at normal membrane resting potentials. Second, the receptor permits a significant influx of Ca2+, and increases in levels of the second messenger Ca2+ can activate a variety of processes that alter the properties of the neuron. Excess Ca2+ is also toxic, and the hyperactivation of NMDA receptors is thought to contribute to a variety of neurodegenerative disorders.

The NMDA receptor binds a large number of distinct pharmacological compounds. For example, certain hallucinogenic compounds, such as phencyclidine (PCP) and dizocilpine (MK-801), are effective blockers of the ion channel associated with the NMDA receptor (Fig. 8.7). These potent antagonists require the channel to be open to gain access to their binding sites and therefore are referred to as open-channel blockers. They also become trapped when the channel closes and are difficult to wash out once bound. Antagonists for the glutamate-binding site also have been developed, and some of the most well known are AP-5 and AP-7. These and other glutamate-binding site antagonists also produce hallucinogenic effects in humans. NMDA remains a specific agonist for this receptor; however, it is about one order of magnitude less potent than L-glutamate for receptor activation. L-Glutamate is the predominant endogenous neurotransmitter that activates the NMDA receptor; however, L-aspartate can also activate the receptor, as can an endogenous dipeptide in the brain, N-acetylaspartylglutamate (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994).

Figure 8.7 Diagram of an NMDA receptor highlighting binding sites for numerous agonists, antagonists, and other regulatory molecules. The location of these sites is a crude approximation for the purpose of discussion.

Adapted from Hollmann and Heinemann (1994).

NMDA Receptor Subunits Show Similarity to Non-NMDA Receptor Subunits

The first cloned NMDA subunit was named NMDAR1 (now termed GluN1), and the deduced amino acid sequence indicated a protein of approximately 97 kDa, similar to other members of the GluR family. Four potential transmembrane domains were identified, and four individual subunits are thought to compose the macromolecular NMDA receptor complex. However, recall that the transmembrane organization of GluR subunits indicates that TM2 forms a reentrant loop in the membrane (Fig. 8.6), and it is assumed that NMDA receptor subunits will also follow this structural topology (Fig. 8.7). The TM2 segment of each subunit clearly lines the pore of the NMDA receptor channel. In fact, a single Asn residue in TM2, analogous to that in the GluA2 subunit, regulates the Ca2+ permeability of the NMDA receptor.

Three of the best-characterized facets of the NMDA receptor were found when the GluN1 subunit was initially expressed in oocytes, although currents were unusually small. These characteristics are (1) a Mg2+-dependent, voltage-sensitive ion channel block, (2) a glycine requirement for effective channel opening, and (3) Ca2+ permeability. However, these initial expression studies were complicated by the apparent endogenous expression of other GluN-like subunits. No glutamate-stimulated current is found when GluN1 is expressed in mammalian cells and the NMDAR is now recognized to exist in the nervous system as obligate heteromers of GluN1 mixed with other subunits (Traynelis et al., 2010).

Several other members of the NMDA receptor family have been cloned (GluN2A–2D and GluN3A and GluN3B), and their deduced primary structures are highly related to each other and to other GluRs (see Fig. 8.2). These GluN receptor subunits do not form channels when expressed singly or in combination unless they are coexpressed with GluN1. Apparently, GluN1 serves an essential role for the formation of a functional pore by which activation of NMDA receptors permits the flow of ions. The native NMDA receptor is thought to be composed of two GluN1 subunits and either two GluN2 subunits or a combination of GluN2 and GluN3 subunits. The GluN1 or GluN3 subunits provide the glycine-binding site for the receptor, while the GluN2 subunits contain the glutamate binding sites (Traynelis et al., 2010). The C-terminal domains of GluN2A–GluN2D are quite large relative to the GluN1 C-terminus and appear to play roles in altering channel properties and in determining the subcellular localization of the receptors. All the NMDAR subunits have an Asn residue at the critical point in the TM2 domain essential for producing Ca2+ permeability. This Asn residue also appears to form at least part of the binding site for Mg2+, indicating that the sites for Mg2+ binding and Ca2+ permeation overlap.

The distribution of GluN2 subunits generally is more restricted than the homogeneous distribution of GluN1, with the exception of GluN2A, which is expressed throughout the nervous system. GluN2C is restricted mostly to cerebellar granule cells, whereas 2B and 2D exhibit broader distributions. As noted, the large size of the C terminus of the GluN2 subunit suggests a potential role in association with other proteins, possibly to target or restrict specific NMDA receptor types to areas of the neuron (see below). Mechanisms related to receptor targeting now are becoming understood and will clearly play major roles in determining the efficacy of synaptic transmission.

Additional NMDA Receptor Diversity Occurs through RNA Splicing

At least eight splice variants now have been identified for the GluRN1 subunit and these variants produce differences, ranging from subtle to significant, in the properties of the expressed receptor (Hollmann & Heinemann, 1994; Traynelis et al., 2010). For example, GluN1 receptors lacking a particular N-terminal insert due to alternative splicing exhibit enhanced blockade by protons and exhibit responses that are potentiated by Zn2+ in micromolar concentrations. Zn2+ classically has been described as an NMDA receptor antagonist that significantly blocks its activation. Clearly, the particular splice variant incorporated into the receptor complex affects the types of physiological response generated. Spermine, a polyamine found in neurons and in the extracellular space, also slightly increases the amplitude of NMDA responses, and this modulatory effect also appears to be associated with a particular splice variant. The physiologic role of spermine in regulating NMDA receptors remains unclear.

NMDA Receptors Exhibit Complex Channel Properties

The biophysical properties of the NMDA receptor are complex. Single-channel conductance has a main level of 50 pS; however, subconductances are evident, and different subunit combinations and splice variants produce channels with distinct single-channel properties. A binding site for the Ca2+-binding protein calmodulin also has been identified on the GluN1 subunit. Binding of Ca2+–calmodulin to NMDA receptors produces a fourfold decrease in open-channel probability. Ca2+ influx through the NMDA receptor could induce calmodulin binding and lead to an immediate short-term feedback inhibition, decreasing ion flow through the receptor.

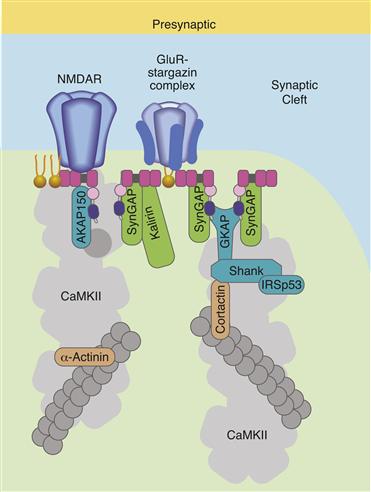

Glutamate Receptors Cluster at Synapses

Glutamate receptors are concentrated at excitatory synapses through interactions with underlying scaffolding molecules (Fig. 8.8). These scaffolding molecules and a host of other structural and signalling proteins form an electron dense structure at excitatory synapses called the postsynaptic density (PSD). One of the best known of these scaffolds is PSD95, a multidomain protein enriched at excitatory synapses that helps organize receptors and signalling molecules. Through one of its multiple PDZ domains, PSD95 binds directly to the cytoplasmic domain of GluN2 subunits and anchors them tightly to the PSD (Sheng & Hoogenraad, 2007). In fact, biochemically isolated PSDs stripped of the overlying membrane retain GluNs indicating the interaction is mediated by tight binding. A number of other PSD enriched proteins have been identified to bind to the C-terminal domain of GluN receptor subunits, including the Ca2+/calmodulin-activated protein kinase CaMKII (Fig. 8.8).

Figure 8.8 Diagram of glutamate receptor clustering at an excitatory synapse. The NMDA receptor interacts directly with PSD-95 through binding to one of PSD-95’s three PDZ domains (the PDZ domains of PSD-95 are shown as pink squares). The AMPAR is associated with a protein called stargazin and stargazin interacts with one of the PDZ domains of PSD-95. Only a few of the many other signaling and scaffolding proteins at excitatory synapses are shown. AKAP150 is A-kinase anchoring protein of 150 kDa that binds to protein kinase A and other proteins, SynGAP is an abundant synaptic associated Ras GTP-ase activating protein that interacts with PSD-95, GKAP is a guanylate kinase associated protein that interacts with PSD-95, CaMKII is an abundant Ca2+/calmodulin-activated protein kinase that interacts directly with the NMDAR. CaMKII also interacts with itself and with α-actinin, which is an actin-binding protein. This web of protein-protein interactions forms the electron dense structures called the postsynaptic densities visible in electon micrographs of excitatory synapses.

Adapted from Sheng and Hoogenraad (2007).

GluA receptors do not interact directly with PSD-95, and their relative concentration in the PSD is dynamic. The up- and down-regulation of GluA receptor number in the postsynaptic membrane alters the efficiency of synaptic transmission and provides a mechanism for the expression of plasticity at excitatory synapses. One accessory protein factor important for receptor trafficking is the protein stargazin that was recently discovered as a structural component of isolated GluA receptors. Stargazin is one member of a family of proteins called TARPs for transmembrane AMPA receptor regulatory proteins that are important for the maturation and targeting of GluA receptors to excitatory synapses (Fig. 8.8). TARPs bind tightly to GluA receptors and they can be identified as additional protein density in electron microscopic reconstructions of isolated GluA receptors (Nakagawa et al., 2005). This situation is analogous in most respects to that described for rapsyn binding to the nAChR (Fig. 8.5). However, TARPs are themselves membrane-spanning proteins, having four predicted TM domains. TARPs also have a domain that interacts with PSD-95 (or other PDZ containing proteins), and it is this interaction that leads to the association of GluA receptors with PSDs. TARPs also affect the maturation and channel properties of GluA receptors in addition to their role in synaptic targeting. Interestingly, TARP binding decreases when glutamate binds to the receptor suggesting interplay exists between receptor use and TARP mediated localization. There are other well-documented proteins that interact with the C-terminal domain of GluA receptor subunits, some in a subtype specific manner. This list includes GRIP/ABP, PICK-1, NSF, and SAP-97, and these proteins have likewise been implicated in the maturation and trafficking of GluA receptors. It is also well documented that specific residues in the C-terminal domain of GluA receptors are phosphorylated and phosphorylation regulates channel properties and surface expression (Traynelis et al., 2010). These post-translational modifications and interactions with other proteins must work in concert for the proper localization and stability of non-NMDA receptors at synapses.

Summary

A general model for ionotropic receptors has emerged mainly from analyses of the nAChR. Ionotropic receptors are large membrane-bound complexes generally composed of five subunits. The subunits each have four transmembrane domains, and the amino acids in TM2 form the lining of the pore. Transmitter binding induces rapid conformational changes that are translated into an increase in the diameter of the pore, permitting ion influx. Cation or anion selectivity is obtained through the coordination of specific negatively or positively charged amino acids at strategic locations in the receptor pore. Glutamate receptors are structurally distinct from the nAChR family of receptors and a major advancement in defining these differences came from the successful crystallization of the GluR2 receptor. This and previous results showed that the TM2 domain of glutamate receptors forms a hairpin instead of traversing the membrane completely, causing the remainder of the receptor to adopt a different subunit topology than that described for the nAChR family. Glutamate receptors are also composed of four, not five, subunits. These differences are perhaps not surprising given that the nAChR family and the glutamate receptor family have arisen from two different ancestral genes.

G-Protein Coupled Receptors

The number of members in the G-protein coupled receptor family is enormous, with over 800 identified from sequencing of the human genome. Historically, the term metabotropic was used to describe the fact that intracellular metabolites are produced when these receptors bind ligand. However, there are now clearly documented cases where the activation of “metabotropic” receptors does not produce alterations in metabolites but instead produces their effects by interacting with G-proteins that directly alter the behavior of ion channels. Thus, these receptors are now referred to as G-protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs). Currently, the GPCR family can be divided into three subfamilies on the basis of their structures: (1) the rhodopsin-adrenergic receptor subfamily (class A), (2) the secretin-vasoactive intestinal peptide receptor subfamily (class B), and (3) the metabotropic glutamate receptor subfamily (class C).

When a GPCR is activated, it couples to a G-protein initiating the exchange of GDP for GTP, activating the G-protein (Fig. 8.1B). Activated G-proteins then couple to downstream effectors to alter the activity of other intracellular enzymes or ion channels. Many of the G-protein target enzymes produce diffusible second messengers that stimulate further downstream biochemical processes, including the activation of protein kinases (see Chapter 9). Time is required for each of these coupling events, and the effects of GPCR activation are typically slower in onset than those observed following the activation of ionotropic receptors. Because there is a lifetime associated with each intermediate, the effects produced by GPCR activation are also longer in duration than those produced by the activation of ionotropic receptors. Most small neurotransmitters, such as ACh, glutamate, 5-HT, and GABA, can bind to and activate both ionotropic and GPCRs. Thus, each of these transmitters can induce both fast responses (milliseconds), such as typical excitatory or inhibitory postsynaptic potentials, and slow-onset and longer duration responses (from tenths of seconds to, potentially, hours). These effects span a broad range of time domains providing the nervous system with a rich source for temporal information processing that is subject to constant modification.

GPCR Structure Conforms to a General Model

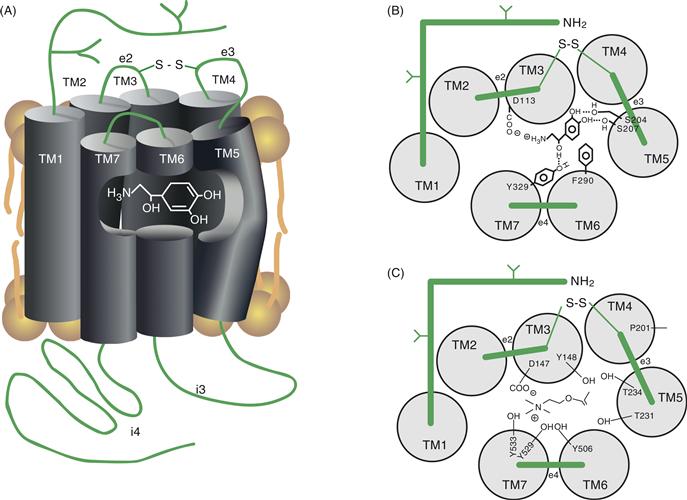

A GPCR typically consists of a single polypeptide with a generally conserved structure; however, there are now clear examples where functional GPCRs are composed of dimers. The receptor subunits contain seven helical segments that wrap back and forth through the membrane (Fig. 8.9). GPCRs are homologous to rhodopsin, and detailed structural information on rhodopsin was originally used to provide a framework for describing other GPCR structures. However, there are now crystal structures available for the human adenosine (A2a) receptor, the human D3 receptor, the human β2 adrenoreceptor, and the avian β1 adrenoreceptor that provide important comparisons to describe the unique and conserved features of GPCR structure.

Figure 8.9 (A) Diagram showing the approximate position of the catecholamine-binding site in the βAR. The transmitter-binding site is formed by amino acids whose side chains extend into the center of the ring produced by the seven transmembrane domains (TM1–TM7). Note that the binding site exists at a position that places it within the plane of the lipid bilayer. (B) A view looking down on a model of the βAR identifying residues important for ligand binding. The seven transmembrane domains are represented as gray circles labeled TM1 though TM7. Amino acids composing the extracellular domains are represented as green bars labeled e1 through e4. The disulfide bond (–S–S–) that links e2 to e3 is also shown. Each of the specific residues indicated makes stabilizing contact with the transmitter. (C) A view looking down on a model of the mAChR identifying residues important for ligand binding. Stabilizing contacts, mainly through hydroxyl groups (-OH), are made with the transmitter on four of the seven transmembrane domains. The chemical nature of the transmitter (i.e., epinephrine versus Ach) determines the type of amino acids necessary to produce stable interactions in the receptor-binding site (compare B and C).

Adapted from Strosberg (1990).

The most conserved feature of GPCRs is the seven membrane-spanning segments; however, other generalities can be made about their structure. The N terminus of the receptor extends into the extracellular space, whereas the C terminus resides within the cytoplasm (Fig. 8.9A). Each of the seven TM domains between N and C termini consists of approximately 24 mostly hydrophobic amino acids. These seven domains associate together to form an oblong ring within the plasma membrane (Fig. 8.9B). Between each transmembrane domain is a loop of amino acids of various sizes. The loops connecting TM1 and TM2, TM3 and TM4, and TM5 and TM6 are intracellular and are labeled i1, i2, and i3, respectively, whereas those between TM2 and TM3, TM4 and TM5, and TM6 and TM7 are extracellular and are labeled e1, e2, and e3, respectively (see Fig. 8.9A).

The Neurotransmitter-Binding Site is Buried in the Core of the Receptor

The neurotransmitter-binding site for class A GPCRs resides within a pocket formed in the center of the seven membrane-spanning segments (Fig. 8.9). In the βAR, this pocket resides approximately 11 Å into the hydrophobic core of the receptor, placing the ligand-binding site within the plasma membrane lipid bilayer (Kobilka, 1992; Rosenbaum, Rasmuseen & Kobilka, 2009). Strategically positioned charged and polar residues in the membrane-spanning segments point inward into a central pocket that forms the binding site for the ligand. For example, Asn residues in the second and third segments, two Ser residues in the fifth segment, and a Phe residue in the sixth segment provide major contact points in the βAR-binding site for the transmitter (Fig. 8.9B; Kobilka, 1992). Replacing the Asp in TM3 with a Glu reduced transmitter binding by more than 100-fold, and replacement with a less conserved amino acid, such as Ser, reduces binding by more than 10,000-fold. Two Ser residues in TM5 are also essential for efficient transmitter binding and receptor activation, as is an Asp residue in TM2 and a Phe residue in TM6. In total, the two Asp, the two Ser, and the Phe residues are highly conserved in all receptors that bind catecholamines. Variations in the amino acids at these five positions appear to provide specificity between the binding of different transmitters to the individual GPCRs.

The neurotransmitter-binding site of mAChRs, like that of the β2AR, has been investigated in great detail (Fig. 8.9C). The Asp residue in TM3 is also critical for ACh binding to mAChRs. Mutagenesis studies indicate important roles for Tyr and Thr residues in TM3, TM5, TM6, and TM7 in contributing to the ligand-binding site for ACh. Interestingly, many of these mutations do not affect antagonist binding, indicating that distinct sets of amino acids participate in binding agonists and antagonists. When the transmembrane domains are examined from a side view (Fig. 8.9A), the key amino acids implicated in agonist binding lie at about the same level within the core of the receptor structure, buried approximately 10–15 Å from the surface of the plasma membrane. An additional amino acid identified as essential for agonist binding of the mAChR is a Pro residue in TM4 (P201 in Fig. 8.9C). This residue is also highly conserved among GPCRs, and structural predictions suggest that it affects ligand binding not by interacting with agonist directly but by stabilizing a conformation essential for high-affinity binding. Structural predictions also place this Pro residue in the same plane as the Asp, Tyr, and Thr residues that form the ligand-binding site of the mAChR.

Transmitter Binding Causes a Conformational Change in the Receptor and Activation of G-Proteins

Proposed models for GPCR activation assume that the receptor can isomerize spontaneously between inactive and active states although there is significant evidence of additional intermediate states along this pathway. Agonist binding stabilizes the active conformation and shifts the equilibrium toward the active form, and G-protein activation ensues. In the absence of agonist, the inactive state of GPCRs is favored, and little G-protein activation occurs. This kinetic model indicates that agonist binding is not necessary for the receptor to undergo transition into the active state; instead, it stabilizes the activated state of the receptor. This model is supported by observations of both spontaneously arising and engineered mutants of the βAR and αAR that can express constitutive activity in the absence of agonist. The mutants stabilize the active conformation of the molecule in a state more similar to the agonist-bound form of the receptor, leading to productive interactions with G proteins. Stabilization of intermediate states by pharmacological agents can explain how certain drugs produce full agonist, partial agonist, neutral antagonist or inverse agonist behavior (Rosenbaum et al., 2009).

The Third Intracellular Loop Forms a Major Determinant for G-Protein Coupling

Extensive studies using site-directed mutagenesis and the production of chimeric molecules have revealed the domains and amino acids essential for G-protein coupling to GPCRs. Receptor domains within the second (i2) and third (i3) intracellular loops (Fig. 8.9) appear largely responsible for determining the specificity and efficiency of coupling for adrenergic and muscarinic cholinergic receptors and are the likely sites for G-protein coupling of the entire GPCR family. In particular, the 12 amino acids of the N-terminal region of the third intracellular loop significantly affect the specificity of G-protein coupling. Other regions in the C terminus of the third intracellular loop and the N-terminal region of the C-terminal tail appear to be more important for determining the efficiency of G-protein coupling than for determining its specificity (Kobilka, 1992). The third intracellular loop varies enormously in size among the different G-protein-coupled receptors, ranging from 29 amino acids in the substance P receptor to 242 amino acids in the mAChR (Strader, Fong, Tota, Underwood, & Dixon, 1994). The intracellular loop connecting TM5 and TM6 is the main point of receptor coupling to G-proteins, and ligand binding to amino acids in TM5 and TM6 may be responsible for triggering the G-protein–receptor interaction by transmitting a conformational change to the third intracellular loop.

Specific Amino Acids Are Involved in Transducing Transmitter Binding into G-Protein Coupling

Residues associated with transmitting the conformational change induced by ligand binding to the activation of G-proteins have been investigated with the use of mAChRs. These studies revealed that an Asp residue in TM2 is important for the receptor activation of G-proteins, and altering the Asp by site-directed mutagenesis has a major negative effect on G-protein–receptor activation. A Thr residue in TM5 (T231 in Fig. 8.9C) and a Tyr residue in TM6 (Y506 in Fig. 8.9C) are also essential. Because these residues are connected by i3, they are assumed to play fundamental roles in transmitting the conformational change induced by ligand binding to the area of i3 essential for G-protein coupling and activation. When mutated, a Pro residue on TM7 (part of a conserved AsnProXXTyr motif) produces a major impairment in the ability of the TM3 segment to induce G-protein coupling. The specifics of these earlier mutagenesis studies have largely been confirmed by comparison of different crystallized forms of the GPCRs and the term “rotamer toggle switch” is used to capture the conformational transition from the inactive to active conformations. There is also a highly conserved sequence AspGluArgTyr in TM3 and a Glu reside in TM6 that forms a series of interactions termed the “ionic lock” that help stabilize the inactive conformation (Rosenbaum et al., 2009). Disruption of this interaction is thought to be an important step in inducing the active conformation capable of productive G-protein interactions.

As mentioned earlier, GPCRs are often single polypeptides; however, they are clearly separable into distinct functional domains. For example, β2AR can be physically split, with the use of molecular techniques, into two fragments: one fragment containing TM1–TM5 and the other containing TM6 and TM7. In isolation, neither of these fragments can produce a functional receptor; however, when coexpressed in the same cell, functional β2ARs that can bind ligand and activate G-proteins are produced. This remarkable experiment indicates that physical connection in the primary sequence is not essential for producing functional β2ARs and also emphasizes the contribution of domains in the separate fragments (TM1–TM5 and TM6 and TM7) to both ligand binding and G-protein coupling.

GPCRs Also Exist as Homo- or Hetero-oligomers

The observation that GPCRs can be physically split through genetic engineering, but produced functional channels when recombined, provided the first hint that full-length GPCRs might also oligomerize with each other into functional molecules. A test of this hypothesis was accomplished by making chimeric receptors composed of TM1–5 of the α2-AR and TM6 and 7 of the m3 muscarinic receptors and vice versa. When either of these chimeric molecules was expressed in isolation, neither formed a functional receptor. However, when coexpressed, receptors were formed that bind both muscarinic and adrenergic ligands and ligand binding led to functional activation of downstream effectors. Through domain swapping, the ligand-binding sites for both receptor ligands were reconstituted by oligomerization of the two chimeric receptors into one bifunctional chimeric dimer. It is now clear that oligomerization of GPCRs into homo- or hetero dimers is adding a new layer of complexity and diversity to the study of these receptors. Important functional consequences could relate to alterations in (1) ligand binding, (2) efficiency and specificity of coupling to downstream effectors, (3) subcellular localization, and (4) receptor desensitization. The evolving and apparently widespread nature of direct receptor–receptor interactions leads one to believe that our current understanding of GPCRs and their biological impact will be undergoing continual modifications for many years to come.

G-Protein Coupling Increases Affinity of the Receptor for Neurotransmitter

The affinity of a GPCR for agonist increases when the receptor is coupled to the G-protein. This positive feedback effectively increases the lifetime of the agonist-bound form of the receptor by decreasing the dissociation rate of the agonist. An excellent demonstration of this effect comes from studies using engineered βAR receptors that are constitutively active in their ability to couple to G-proteins. These mutant receptors show a significantly increased affinity for agonists. When the G-protein dissociates, the agonist-binding affinity of the receptor returns to its original state. Changes induced by ligand binding apparently stabilize the receptor in a conformation with both higher affinity for ligand and higher affinity for coupling to G-proteins.

Specificity and Potency of G-Protein Activation Are Determined by Several Factors

GPCRs associate with G-proteins to transduce ligand binding into intracellular effects. This coupling step can lead to diverse responses, depending on the type of G-protein and the type of effector enzyme present. Ligand binding to a single subtype of GPCR can activate multiple G-protein-coupled pathways. For example, activated α2ARs have been shown to couple to as many as four different G-proteins in the same cell (Strader et al., 1994). Some of the specificity for G-protein activation can be determined by the specific conformations assumed by the receptor, and a single receptor can assume multiple conformations. For example, α2ARs can isomerize into at least two states. One state interacts with a G-protein that couples to phospholipase C, and a second state interacts with G-proteins that couple to both phospholipase C and phospholipase A2. Thus, a single GPCR can produce a diversity of responses, making it difficult to assign specific biological effects to individual receptor subtypes in all settings.

Activated GPCRs are free to couple to many G-protein molecules, permitting a significant amplification of the initial transmitter-binding event. This catalytic mechanism is referred to as “collision coupling,” whereby a transient association between the activated receptor and the G-protein is sufficient to produce the exchange of GDP for GTP, activating the G-protein. For example, because adenylyl cyclase appears to be tightly coupled to the G-protein, the rate-limiting step in the production of cAMP is the number of successful collisions between the receptor and the G-protein. A constant GTPase activity hydrolyzes GTP, bringing the G-protein and therefore the adenylyl cyclase back to the basal state. The apparent maximal rate is achieved when all the G-protein–cyclase complexes have become activated or, more accurately, when the rate of formation is maximal with respect to the rate of GTP hydrolysis. Additionally, the important process of receptor desensitization can also regulate the number of receptors capable of productive G-protein interactions.

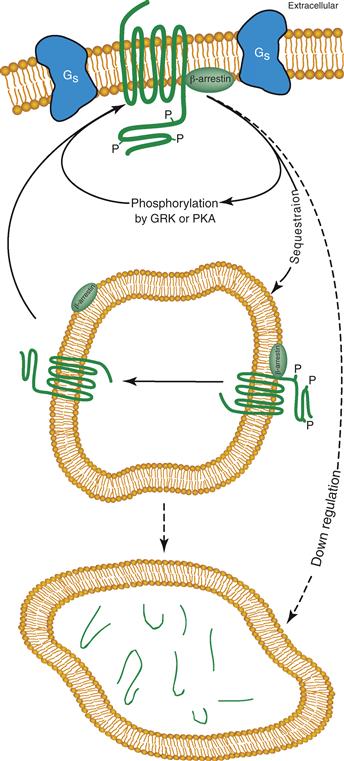

Receptor Desensitization is a Built-in Mechanism for Decreasing the Cellular Response to Transmitter

Desensitization is an important process whereby cells can decrease their sensitivity to a particular stimulus to prevent saturation of the system (Kobilka, 1992; Rosenbaum et al., 2009). For GPCRs, desensitization is defined as an increase in the concentration of agonist required to produce half-maximal stimulation of, for example, adenylyl cyclase. In practical terms, desensitization of receptors produces less response for a constant amount of transmitter.

There are two known mechanisms for desensitization. One mechanism is a decrease in response brought about by the covalent modifications produced by receptor phosphorylation and is quite rapid (seconds to minutes). The other mechanism is the physical removal of receptors from the plasma membrane (through a mechanism of receptor-mediated endocytosis) and tends to require greater periods of time (minutes to hours). The latter process can be either reversible, where receptors are sequestered but are recycled to the plasma membrane or irreversible, where the receptors are removed from the cell through degradation (Fig. 8.10).

Figure 8.10 Intracellular pathways associated with desensitization of GPCRs. GPCRs are phosphorylated (noted with P) on their intracellular domains by PKA, GRK, and other protein kinases. The phosphorylated form of the receptor can be removed from the cell surface by a process called sequestration with the help of the adapter protein β-arrestin; thus fewer binding sites remain on the cell surface for transmitter interactions. In intracellular compartments, the receptor can be dephosphorylated and returned to the plasma membrane in its basal state. Alternatively, phosphorylated receptors can be degraded (down regulated) by targeting to a lysosomal organelle. Degradation requires replenishment of the receptor pool through new protein synthesis.

Adapted from Kobilka (1992).

The Rapid Phase of GPCR Desensitization is Mediated by Receptor Phosphorylation

Desensitization of the βAR appears to involve at least three protein kinases: PKA, PKC, and a G-protein receptor kinase (GRK). Phosphorylation of ARs by PKA does not require that the agonist be bound to the receptor and appears to be a general mechanism by which the cell can reduce the effectiveness of all receptors, independent of whether they are in the agonist-bound or unbound state. This process is also referred to as heterologous desensitization because the receptor does not require bound-agonist. PKA and PKC phosphorylate sites on the third intracellular loop and possibly the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain. Phosphorylation of these sites interferes with the ability of the receptor to couple to G-proteins, thus producing the desensitization.

GRKs can also phosphorylate GPCRs and lead to receptor desensitization. Six members of the GRK family of kinases have been identified: rhodopsin kinase (GRK1), βARK (GRK2), and GRK3 through GRK6 (Huang & Tesmer, 2011; Premont, Inglese, & Lefkowitz, 1995). GRK2 is a Ser and Thr specific protein kinase initially identified by its capacity to phosphorylate the βAR. GRK2 phosphorylates only the agonist-bound form of the receptor, usually when agonist concentrations reach the micromolar level, as typically found in the synaptic cleft. This process is referred to as homologous desensitization because the regulation is specific for those receptor molecules that are in the transmitter-bound state. Phosphorylation of βAR by GRK2 does not interfere with coupling to G-proteins directly. Instead, an additional protein, arrestin, binds the GRK2-phosphorylated form of the receptor, thus blocking receptor–G-protein coupling (Fig. 8.10). This process is analogous to the desensitization of the light-sensitive receptor molecule rhodopsin produced by GRK1 phosphorylation and the binding of arrestin. Phosphorylation sites on βAR for GRK2 reside on the C-terminal cytoplasmic domain and are distinct from those phosphorylated by PKA.