COALITION OPERATIONAL ART IN 1799

Suvorov and Masséna in Italy and Switzerland

CHRONOLOGY

| October 1797 | France and Austria signed Treaty of Campo Formio |

| Jul 1798 | Napoleon led an army to capture Egypt |

| Aug 1–2, 1798 | Admiral Nelson destroyed French Fleet at the battle of the Nile |

| 1799–1801 | The War of the Second Coalition |

| March 1, 1799 | French attacked Austrians in Germany and Switzerland |

| March 7 | Masséna won battle at Chur |

| March 25 | Archduke Charles defeated French at Stockach |

| March 26 | Masséna captured Martinsbruck in Austrian Tyrol |

| April 5 | Austrians won Battle of Magnano near Verona |

| April 14 | Marshal A. V. Suvorov took command of the Allied army in Italy |

| April 26–28 | Suvorov’s army forced Adda River line |

| April 29 | Allies “liberated” Milan |

| June 3–4 | Masséna repulsed Archduke Charles at the First Battle of Zurich |

| June 17–19 | Battle on the Trebbia River, Suvorov defeated Macdonald |

| July 27 | French garrison of Mantua surrendered to Allies |

| August 15 | Allied army under Suvorov smashed French at Novi |

| August 17 | Archduke Charles began marching north to Germany |

| August 25 | Suvorov and Russian army ordered to Switzerland |

| September 25–26 | Masséna won the Second Battle of Zurich |

| October 5 | Suvorov retreated over the Alps |

| November | Bonaparte returned to Paris a hero after abandoning his army in Egypt and established himself as First Consul |

| October 22 | Tsar Paul withdrew Russia from the Second Coalition |

Operational art executed on behalf of a single political entity, whatever its many goals, is simpler than in an alliance or coalition construct. In chapter 2 concerning 1796–1797, the operational artist Napoleon Bonaparte had only one constituency to satisfy with his “work”—the government of France. In coalition warfare, the situation is much more demanding and complex for the operational artist—he or she must satisfy more than one political master, although certainly the priority goes to the state from which the general originates or to whom he has sworn service (not always the same in that era of cosmopolitan 18th-century generals). For example, Dwight D. Eisenhower served U.S. interests in World War II while at the same time trying to also satisfy the political interests and agendas of his sometimes troublesome allies, the French and the British. The point to be made here is that when campaigns are designed to accomplish military objectives that lead to political results, this is often more difficult in a coalition construct than without it. Napoleon’s foreign minister, Charles-Maurice de Talleyrand, derided coalition warfare during the period (referencing Prussia and Austria): “We [French] have given up fearing coalitions: there is a principle of hatred, jealousy and distrust between the Cabinets of Berlin and Vienna which will guide them above all else.”1

Into this difficult mix arrived the towering personality of Marshal A. V. Suvorov in command of an Austro-Russian coalition army. Suvorov had fought the Prussians in the Seven Years’ War and had been one of Catherine the Great’s most successful generals against the Turks and the Poles.2 At this time his reputation as a great general was well established, being on par with Napoleon Bonaparte, Saxe-Coburg (whom Suvorov had asked be appointed to command in Germany), and Archduke Charles. Suvorov was charged with nothing less than reconquering Bonaparte’s Italian gains for Austria while that general remained cut off with the French expedition to Egypt.3 Suvorov is of particular interest because later Soviet historiography and military writing identified him as a sort of prototype for the ideal Russian operational artist—especially his very advanced ideas on the importance of training troops.4

Secondarily, the operations of Général de Division Andre Masséna in Switzerland will also be examined. Masséna’s operations are critical to understanding the flow of operations in Italy, but ultimately Massena’s successful campaign in Switzerland, along with a disastrous Anglo-Russian campaign in Holland, were major causes of Russia leaving the coalition and the war. Finally, Masséna’s operations provide further evidence of an operational artist hard at work against a superior foe, mixing offense and defense in the right amounts to overcome difficult challenges and in no small measure prevent the invasion of France by victorious Austrian and Russian armies.

THE CAUSES OF THE WAR OF THE SECOND COALITION

As mentioned in chapter 2, the events that led to the outbreak of war had their roots in the incomplete peace agreed to by the French and Austrians at Campo Formio in 1797. However, French actions and provocations played an equally important role. Also, to understand the operational-level interactions, it is necessary to grasp the political context for the fighting, especially in the Italian theater of operations. The Second Coalition has been much criticized—yet, as we will see, it came very close to success. Of all the anti-French coalitions formed before 1813, it superficially resembled the successful coalition that emerged 14 years later in 1813. The coalition armies in both contests outnumbered the thinly stretched French forces at the beginning of the respective campaigns. As in 1813, a significant reason for the lack of veteran cadres for a continental contest would be Napoleon Bonaparte, cut off in Egypt with the cream of the French army in 1799 and by his own disastrous retreat from Russia in 1812 (see chapter 7). General war weariness and disillusionment with the French “liberators” in the European territories they now “defended” was also a common trait for both 1799 and 1813. Similarly, rebellions in Naples and Switzerland foreshadowed the mix of conventional and guerilla warfare later in Spain, Russia in 1812, and Germany in 1809 and 1813.

Austria signed the Treaty of Campo Formio in 1797 but Great Britain continued to fight because of French domination of the Low Countries and the resultant closure of these ports to British trade. Also, the specter of a unified Franco-Dutch fleet posed an even greater nightmare for the politicians in London than the economic predicament (see chapter 4). Great Britain redoubled her efforts to find continental allies, but for all intents and purposes she remained alone against France. The Franco-Austrian peace followed a common pattern for treaties during the entire Napoleonic era: it included both open and “secret” provisions. The secret provisions allowed the French and Austrians to get around other obligations that they had incurred in previous treaties, making for realpolitik diplomacy in this period as cynical as any in the modern era. The secret clauses in Campo Formio included recognition of the Rhine as a “natural boundary” for France, yet the details of this boundary remained unresolved. These continuing issues along the Rhine and Austria’s foothold in Italy presaged a likely conflict in the future. French revolutionary leader Abbé Sieyès summed it up best, “This treaty is not peace: it is a call to new war.”5

Great Britain regarded these treaties as outright betrayal. To make matters worse, Austria defaulted on her loan convention with Great Britain. This one issue was to poison the atmosphere between the two countries that needed to cooperate most in their war against France. Austria was under no illusions about a future conflict with France. As a result, the two most inveterate foes of revolutionary France barely communicated with each other while their respective leaders negotiated for the creation of a new coalition. The dispute came to a head in May 1797 when the Austrian Foreign Minister Baron Thugut refused to ratify a convention for the repayment of Austria’s war loans from Great Britain. Later, when Austria approached Britain in April 1798 with an alliance proposal, it foundered on the rocks of the unratified loan convention. Britain would coordinate, rather than cooperate, with Austria in the war against the French.6

Against this backdrop the French continued their territorial aggrandizement under the guise of peace. French aggression not only provoked an outraged Europe into forming a second coalition but also had the additional effect of further weakening France by overextending her military. The first act of military overextension was Bonaparte’s expedition against Egypt. His purpose was to strike at the British lines of communication with India. One very significant action incidental to this expedition was Bonaparte’s seizure of Malta from the Knights of St. John. Unfortunately for the French, Russian Tsar Paul I was the self-proclaimed protector of this order and aspired to the title of grand master. The Tsar had already been in serious negotiation to field an army against the French. The French conquest of Malta convinced the Tsar to join the ranks of France’s enemies. The other key aspect of the French aggression in the east was the addition of Turkey to the ranks of France’s foes. On September 5, 1798, the Turks allowed a Russian fleet “for one time only” to pass through the Bosporus.7

Bonaparte was not alone among the French in his ability to add enemies to the field against the Republic. Before he departed for Egypt he was already cognizant of the Directory’s plans for new aggression against the Papal States, the United Provinces (Holland), and the Swiss federation. One historian articulates this policy as the “Napoleonic practice of using peace as an extension of war.”8 Two events now occurred in Italy as a prelude to the coming war. Each, in its own way was to affect the Second Coalition’s conduct of operations. The first occurred in the Bourbon Kingdom of Naples. Egged on by the British admiral Horatio Nelson, the hero of the Battle of the Nile, the Bourbons sent their army to “liberate” Rome in December 1798. The French dispersed the Neapolitan forces and then proceeded south and displaced the Bourbon King, conquering his country and establishing the satellite Parthenopian Republic. In a second action, the French convinced the King of Piedmont, Austria’s erstwhile ally, to abdicate to Sardinia. Upon his departure, the Piedmontese army, with his consent, was incorporated into the French forces in Italy. The issue of Piedmont was to cause serious problems for the Second Coalition during Suvorov’s campaigns in 1799.9

In summary, the French had to maintain armies of occupation in Holland, Italy, and Switzerland, to say nothing of Egypt. The situation in Naples was particularly onerous. The French occupation had resulted in a wave of patriotism and resistance by the lazzaroni (beggars) in the cities and the sandfesiti (peasants) in the countryside.10 General (later Marshal) Etienne-Jacques Macdonald, the commander in this sector, commented that “no sooner was insurrection crushed at one point than it broke out in another.”11 British sea power, too, demanded garrison troops along a lengthy, vulnerable coastline that now included Belgium and Italy. Additionally, the threat of a renewed Austro-Russian onslaught in Italy or along the Rhine (including Switzerland) caused the French to maintain substantial armies in response. The Directory prepared to face the armies of the Second Coalition under these considerable constraints. Instead of contracting or withdrawing its forces, the French government adhered to the “principle of keeping everything, and not yielding a foot of ground,” as Macdonald bitterly observed.12

The end of the eventful summer of 1799 saw the Second Coalition poised to achieve the strategic success denied the previous anti-French coalition.13 Indeed, the initial campaigns resulted in both tactical and (by modern standards) operational victory. British sea power had cut off and stalemated General Bonaparte in Egypt while the Archduke Charles defeated or neutralized the French, under Generals Jourdan and Masséna, in southern Germany and Switzerland, respectively. Finally, the Russian field marshal Alexander Suvorov had conquered Italy at the head of a combined Austro-Russian army. Suvorov’s campaign was in many ways as brilliant, and certainly shorter, when compared to Napoleon’s more celebrated 1796–1797 Italian campaign. Suvorov and his Austro-Russian army effectively destroyed one French army (Scherer and Moreau), severely defeated another (Macdonald), and crippled a third (Joubert). Suvorov “liberated” almost the whole of Italy, placing France territorially farther back than the starting point of Napoleon’s 1796 campaign.

Yet, before the year’s end this promising situation had imploded. The Second Coalition collapsed as the Russians withdrew in disgust and became hostile neutrals.14 The final victory that had seemed a certainty in September was doubtful by December. What caused this dramatic and rapid turnabout? In order to understand what happened, and how the brilliant operations of Suvorov in Italy came to naught, we must go back again to the start of the campaign in early 1799.

One must first examine the raw material of Suvorov’s armies—the Russian and Austrian soldiers. Understanding the Russian soldier of this period is the key to understanding the corresponding operations that Suvorov developed on his own initiative. Sir Robert Wilson, the British liaison officer who served extensively in Russia, observed that the Russian soldier “is fearless, disdains the protection of ground, is not intimidated by casualties [italics mine].”15 Archduke Charles thought the “officers and men were poorly trained in tactics and deployments.” Against European armies the Russians normally employed the 18th-century linear formations and against the wilder Turks and Poles they employed columns and squares.16 As for skirmishing, Russian light infantry (jaeger) formations did exist, but skirmishing and independent actions by them were only in the regulations and still in their infancy in terms of actual practice.17 This, then, was the Russian army in 1799: stolid, imperturbable infantry, numerous artillery indifferently served, and clouds of Cossacks. Combined arms action was virtually nonexistent, except, as we shall see, when Suvorov was in command.18 The émigré Frenchman Count Langeron—who was one of the Tsar’s many foreign officers—captures this essence best: “All their principles of war come down to their bayonets and their Cossacks…and all their enterprises have been crowned with success.”19

Their leader in this campaign was truly a “soldier’s general.” Hard on his officers, Suvorov was paternal with his men, caring for their well-being, eating their fare, and sleeping on hay or the ground as they did. He shared their hardships and they idolized him in return. One historian goes so far as to say that only Suvorov, of all the Russian generals before and since, really understood the “potential for…innovation that the Russian peasant soldier afforded” his leaders.20

Another key to understanding Suvorov’s success is to understand his revolutionary methods of training. In simplest terms, Suvorov trained for both the tactical and operational environments. His motto was “train hard, fight easy.” He wrote: “Training is light, the lack of training is darkness…the trained soldier is worth three soldiers who are untrained. No! it’s more than that, say six, still not enough—ten is more like it.”21 He took the basic tactics of the Russian army, modified them to his purposes, and then ruthlessly practiced them with the troops under his command. At the operational level he routinely had his troops make forced marches in peacetime of 26 miles or more to build up their endurance. His soldiers often marched as fast, or even faster, than the average French Revolutionary armies. Perhaps one key to this sort of performance was simply that the other Russian generals did not possess Suvorov’s drive, energy, and impetuousness—character traits necessary for the true operational artist. His practice of combined arms maneuvers prior to engagements is justly famous. He had infantry charge infantry with bayonets leveled and cavalry charge full tilt against infantry who passed them in prearranged corridors only at the last possible second. He also had his cavalry in formation near his cannon when they fired to condition the horses not to panic from this source. Suvorov had his men conduct mock attacks on monasteries to simulate the stone fortresses of Europe.22

Suvorov also practiced what Jomini later called grand tactics, which is the art of arranging and deploying troops on a grand scale for battle prior to actual combat. However, he differed from Jomini by having his troops practice the key transition period between the approach march (operational maneuver) and the actual conduct of the engagement—always tailoring his tactics to suit whichever enemy he faced, whether a formal European army or the more irregular forces of the Poles and Turks (and French). He was particularly adamant that his troops be able to deploy directly from the march into formations based on the terrain. He did this because he was the master of a type of engagement most generals avoided; the meeting engagement or “accidental” battle between two armies on the move and not formally deployed for battle. For Suvorov, though, because of his method, these engagements were almost always deliberate. Bonaparte would later employ the same method with his corpsd’armée. The French had become the reigning masters of this sort of battle with divisions that deployed rapidly into skirmishers, lines, and columns, but they were to meet their match in Suvorov. He practiced a kind of Russian version of John Boyd’s “OODA” cycle (see chapter 1), using surprise, assessment, and speed—what one historian calls his “triad”—to turn the operational and tactical into one dynamic, violent continuum. He trained his soldiers accordingly, making them understand that surprise was normal by introducing it into his training exercises.23

Suvorov explained this method during the 1799 campaign to the Austrian general Bellegarde: “speed and surprise substituted for numbers [while] hitting power and blows decided combat.” He got his striking power from his constant focus on training. Like his counterpart at sea, Lord Nelson, he sought rather than eschewed battle in order to apply that power directly to his surprised enemies. On land he materialized much as Bonaparte had done from unexpected directions and then ruthlessly kept his enemy fixed as other echelons arrived to contribute to his combat power. What is most fascinating about this campaign, his last, is that he obtained a nearly similar result with his Austrian troops that he had not trained. This was a testimony to his methods of leadership but also to the inherent untapped potential of the veteran Austrian troops he employed as part of his army.24

After its numerous defeats during the War of the First Coalition (1792–1797), the Austrian army had attempted to implement new reforms. This effort was first placed in the hands of Archduke Charles, who counseled only minor changes because of the imminent outbreak of another war with France. Charles wrote, “before such changes have been completed for some time, the army will be in disarray and there will be disaster.” Charles was removed and a more pliable military commission replaced him, headed by the same General Alvintzy defeated so handily by Bonaparte at Arcola and Rivoli.25 In the end, the only “reforms” implemented were a new musket, new uniforms, and a superficial reorganization of the army. A good feel for the doctrine is captured in the following excerpt from the book Generals-Reglement of 1769:

Regular, trained, and solid infantry, if it advances in closed ranks with rapid steps, courageously, supported by its artillery, cannot be held up by scattered skirmishers. It should therefore refuse to lose time either by skirmishing or by the fire of small groups…. It should close with the enemy as rapidly and orderly as possible, so as to drive him back and decide the action quickly. This is the method that saves lives; firing and skirmishing costs casualties and decides nothing.26 [emphasis mine]

Tactical instructions issued to General Zach in 1800 echoed this sentiment, indicating that nothing really changed from 1796 to 1799.27

Higher command levels of the Austrian army were still organized along the 18th-century lines and strategic direction provided by the Hofkriegsrat, which was dominated by Baron Thugut. The Hofkriegsrat often caused more disunity in the direction of military affairs than its intended purpose of unification of strategy. Orders sent from Vienna were often irrelevant by the time they reached the commander in the field.28 But this problem was not unique to the Austrians; Napoleon as emperor would have the same problem with his directions to his generals in Spain. The rather large (for that period) Austrian army was extremely expensive to maintain—45 percent of all the Imperial revenue went to its upkeep.29 Austria’s expensive army was essential to her existence as a dynastic state, and therefore was a more intrinsically valuable army from the standpoint of its rulers. This was one of two fundamental differences between the Russian and Austrian armies. High casualties were anathema to Thugut and the Holy Roman emperor. The Russian army, on the other hand, was a tool to expand Russia’s influence in Europe and Tsar Paul’s legacy of glory.30 In the Russian army, casualties were often not a consideration, although Suvorov was more careful of his men’s lives than most of his Russian contemporaries—but ruthless when he sensed victory.

The second fundamental difference between the two armies is related to the first. Russian operations and tactics took advantage of the ability of its soldiers to endure circumstances that the soldiers of other armies could not—in a word, the Russians, and especially Suvorov, molded their maneuvers around the operational durability of the troops. The Russian soldier often executed orders that no other troops of Europe could or would.31 Russian units could endure terrific casualties and still remain cohesive. When one considers these attributes of the Russian army and of their leader, one finds that the French army’s normally asymmetric advantage as a national and durable force composed of highly maneuverable units would count for little in the campaign of 1799 in Italy. Also, Schneider’s requirement for real operational art requires this sort of symmetry—the “distributed” opponents operating in a similar fashion.

The overall Allied strategic plan was to attack France on all fronts, including opening an additional front in Holland by a combined Anglo-Russian force. Initially, the Russians were to have been employed as a component in all theater armies (except Egypt)—Holland, Italy, Switzerland, and Germany. As the various Russian columns made their way through Poland and then into central Europe, however, the French Directory decided to go on the offensive in all theaters. These offensives had the purpose of overall defense, not conquest, essentially as spoiling attacks against the gathering forces of Austria, Russia, and Great Britain. The Directory, despite being spread thin on all fronts, instructed its main field commanders to take the offensive against the superior forces facing them in Italy, Switzerland, and Germany. This strategy was in part meant to hit and throw the Austrians back before the many Russian contingents arrived to reinforce them.32

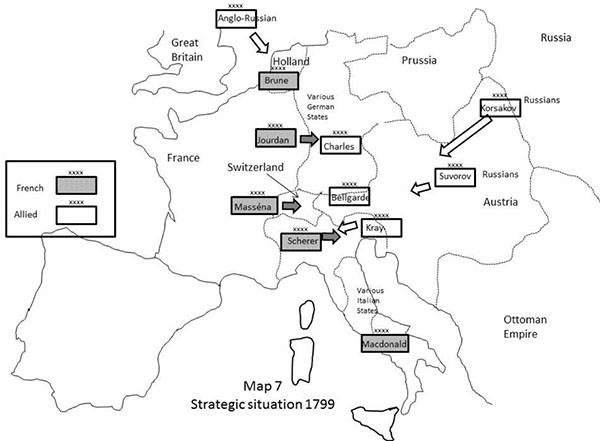

The key area for all the belligerents, as it turned out, would be Switzerland (see map 7), whose terrain controlled the communications for both sides between the major theaters of operation in Italy and Germany. Additionally, whoever held Switzerland could threaten the flanks of their opponent or guard their own flanks for advances in adjacent theaters. The French placed arguably their best available general in command of the Helvetian (Swiss) army, Bonaparte’s most reliable subordinate from his first campaign, General André Masséna. General Scherer, leaving his job as war minister for the Directory, was to have the effort in Italy once again with instructions to go on the offensive against the Austrian forces in northeastern Italy where the Adige served as the frontier between their forces and the French. Because events in Italy would be greatly influenced by Masséna’s fortunes in Switzerland, it is to there we must first go before examining the campaign in Italy.33

Map 7 Strategic situation 1799

PHASE I: SUCCESS IN SWITZERLAND AND DEFEAT IN ITALY

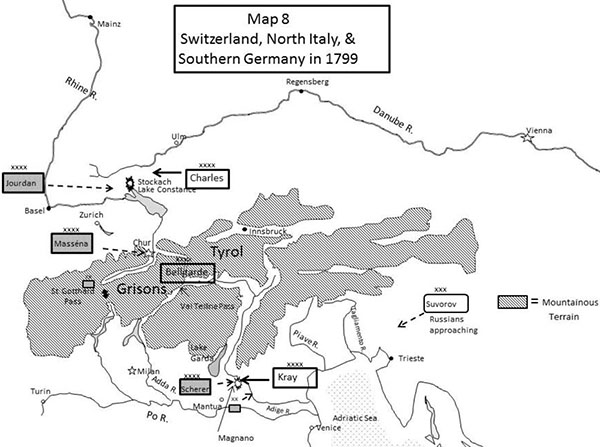

During the brief “interwar” period, the French had done at least one thing right in establishing a Swiss Helvetian Republic and thus gaining many of the hardy Swiss as allies as well as the right to station French troops at most of the key passes in western and central Switzerland. Masséna, the expert at alpine warfare, instinctively knew that his best course of action was to strike where the Austrians were most vulnerable, toward the passes in the southeastern portion of Switzerland known as the Grisons, here he could threaten or even invade the Tyrol, and thus threaten Austria’s communications with both Italy and Germany via the Valtelline Pass (see map 8). Masséna opened his campaign in Switzerland in early March, commanding a force of around 50,000 troops (with 10,000 detached to guard the key St. Gotthard Pass). After additional deductions for key garrisons, passes, and communication, he had approximately 26,000 troops available for field operations. He initiated his offensive a week after the French armies in Germany had opened their campaigns and Masséna clearly caught the Austrians in the Grisons unprepared, achieving tactical and operational surprise.34

Masséna achieved success immediately, driving on Chur, the provincial capital, where he captured 3,000 prisoners on March 7. By March 26, he had entered the Tyrol; however, at this point the failure of Jourdan’s army in Germany undermined Masséna’s astonishing successes. Archduke Charles defeated the badly outnumbered Jourdan at Stockach on March 25 in southern Germany and then drove him back over the Rhine.35 Now Masséna faced the might of Archduke Charles to his north plus the Austrian reserves in the Tyrol under General Bellegarde to his east and south.

Masséna gained command of what was left of Jourdan’s army and now controlled over 70,000 troops, but he was defending from Mainz (Mayence) on the Rhine all the way to Scherer’s area of responsibility in northern Italy. He withdrew from the trap that the western Tyrol had now become, although he retained control over most of the Grisons. On the Rhine he directed his subordinates to conduct an active defense along the Rhine (he remained with the Helvetian army in Switzerland). Austrian pressure eventually forced him to abandon most of the upper Rhine Valley and pull back his main force in Switzerland to the vicinity of Zurich by May 20. Throughout he fought numerous delaying actions as well as battling against Swiss Catholic peasants whom the Austrians had stirred up against his lines of communications. It is at this point we must return to the activities of General Scherer, upon whom the Hungarian general Paul Kray visited a series of defeats without Suvorov or his Russians present. These events forced Masséna to send precious reserves south to shore up the southern front and resulted in his eventual abandonment of Zurich (see map 8).36

The campaign began prior to Suvorov’s assumption of command with French offensives along the upper Rhine in Germany and along the Adige in Italy. The opposing forces in the Italian theater consisted of approximately 120,000 French versus 60,000 Austrians, but a large Russian column under General Rosenberg was rapidly approaching. The French were divided into numerous garrisons (due to simmering rebellion throughout Italy) and two field armies: the Army of Italy under General Barthelmy Scherer in the north (the same general whom Bonaparte had replaced in 1796) and the Army of Naples under General Macdonald in the south. These forces were spread across the length of Italy from the Alps to Naples, resulting in a local superiority for the Austrians along the line of the Adige River.37 The Army of Italy was not the same fearsome force it had been under Bonaparte, however. Upon arriving in Italy on March 21 Scherer found it “indisciplined and disgruntled.” Nevertheless, in accordance with the Directory’s overall strategy, Scherer took the offensive in late March against the Austrian lines. Kray conducted a skillful defense à la Bonaparte along the river line, although he outnumbered Scherer. At first Scherer achieved some success when General Jean Victor Moreau, his second in command, led the left wing against the Austrians near the key terrain south of Rivoli and evicted them. This success did not last long. At the same time, Scherer fixed the Austrians in the fortress of Verona (their fortified bridgehead over the Adige) with the main effort under his personal command while sending a division on a wide flanking movement south of the old Arcola battlefield at Legnano as a diversion. His intent was evidently to pull the Austrians away from Verona and then assault or bypass it and win a battle on Kray’s flank while he was busy to the south. The plan succeeded too well and Kray’s Austrians savaged the division at Legnano, which included the Polish Legion composed of Austrian Polish deserters from Galicia (sometimes known as the Legion of the North). The Austrians attacked with particular fury against the Poles, whom they regarded as traitors, and drove this division back with great loss. The Poles, always good fighters, would be ill-used in this campaign as they fought against their hereditary foes who had partitioned their homeland—the Austrians and Russians.38

Map 8 Switzerland, North Italy & Southern Germany in 1799

Scherer’s column, meanwhile, made great efforts against the Austrians around Verona as Kray’s attention was absorbed in the south, battling for over 18 hours against the local Austrian force of two divisions. Kray, once he realized the deception, moved rapidly through Arcola by a night march in a manner worthy of Bonaparte, and on March 27 he arrived just in time to turn the tables on the French. After two days of confused combat around Verona, the French asked for, and the Austrians granted, a one day truce—Kray well knew that a truce would only work in his favor since the Russians and Suvorov were marching hard to join him. The Austrians had almost 7,000 casualties and the French over 5,000, not including their losses at Legnano. On March 30, Scherer threw Serurier’s division against Kray with disastrous results. The assault failed with over 1,500 French lost to that of barely 400 Austrians. Scherer’s offensive only demoralized his army and cost him casualties he could ill afford.39

Moreau was called in to help Scherer, and predictably the rearguard forces at Rivoli were thrown back. On April 5, Scherer advanced again from his main camp at Magnano against Kray’s forces just west and south of Verona for one more try to break the Hungarian general’s resolve. Even with Moreau and extra reserves brought down from Rivoli, the Austrians had the slight edge in numbers (44,000 compared to the French 40,000) and were buoyed by their recent victories. This was one of the largest battles, both in geographic expanse and numbers of troops, to occur in Italy to this point in the wars and it was a severe French defeat. Kray, an expert in light infantry tactics, used a Suvorov-like tactic in his counterattack that decided the battle, an all-out grenadier attack on Scherer’s right “with fixed bayonets” according to one observer. Kray’s men inflicted over 8,000 casualties on the French, shattering the morale and confidence of Scherer’s troops and their generals. The French fell back to the line of the Mincio River, anchored by the fortresses of Peschiera in the north and Mantua in the south (see chapter 2, map 4).40

The results of Magnano had serious consequences for the French. In addition to pulling back to the Mincio, Scherer recommended Macdonald and the Army of Naples come north, completely abandoning central and southern Italy; he also offered his resignation. At the same time, Scherer learned that General Heinrich Bellegarde, the commander of the Tyrolean army who now had troops to spare with Masséna in retreat, was sending strong flanking forces into his rear on the western side of Lake Garda, as Würmser had tried three years before against Bonaparte. Neither the army nor the general had the nerve for a Castiglione-type maneuver to retrieve the situation and the French were forced back to the Adda River by April 14, while the fortresses of Mantua and Peschiera were placed under siege. These garrisons subtracted another 7,500 troops from the French army, leaving it with less than 26,000 available troops. The Directory accepted Scherer’s resignation and replaced him with General Moreau. The Austrians had good reason to be pleased. These victories, achieved without the assistance of the Russians and Suvorov, had given them a well-deserved pride in their own methods and abilities.41

On April 17, 1799, Suvorov assumed command of the Austrian force, arriving ahead of his own troops, who were at this point marching up to 30 miles a day. A point worth remembering was that the Austrians requested that Suvorov assume the overall command in Italy, even though the Austrians had the preponderance of force. Modern doctrine would have given an Austrian the command.42 Actually, the first choice had not been Suvorov, but a variety of factors, including the untimely death of Frederick of Orange (a Dutch prince originally slated for the overall command) conspired to give the command to Suvorov. He was chosen by default due to his stellar reputation from the Turkish and Polish wars. Suvorov had already done two things to offend his Austrian partners. While in Vienna the old Marshal had refused to discuss his strategic plans with the members of Hofkriegsrat, including Thugut. Suvorov remained uncommunicative on his way to the front with his Austrian chief of staff, General Jaques Gabriel Chasteler, who also attempted to discuss operations with him.43 Even so, when Chasteler arrived ahead of Suvorov at Kray’s Headquarters, he was still bubbling with enthusiasm about his new chief. Chasteler was a figure not unlike Berthier, a professional staff officer of considerable talent, and Suvorov gave him carte blanche in reorganizing all of the Russian and Austrian units “along the most modern lines, transforming [the army] from a collection of individual regiments into permanent multi-regimental all-arms divisions.” Chasteler gave each Austro-Russian division its own staff, composed of trained Austrian staff officers, with one battery each of horse artillery (which was still a recent innovation) and medium artillery, the latter composed of the excellent Austrian 12-pound guns plus one howitzer.44

Suvorov’s second tactless act was to issue a series of instructions to the Austrian officers delineating which tactics to employ and under what specific circumstances. One of Suvorov’s directives detailed that the infantry was to form into “two lines” from the column at one thousand yards from the enemy and then advance slowly to

three hundred yards, this being the maximum range of the excellent French musketry. Then, when the order to advance was given, the troops should proceed at the usual rate, but after a hundred paces they must double their speed, and a hundred yards short of the French line they must rush at it…with bayonets leveled. The second line was to follow through while the first, having delivered their charge, halted and reformed.45 [emphasis mine]

Here was the idea of the echeloned attack (albeit at the tactical level) where the momentum of the offensive could be maintained by a fresh second echelon while the first reconstituted, presumably to be passed through the second echelon at some later point if need be. Suvorov announced to his army that, “We have come to beat the godless, windbag Frenchies. They fight in columns and we will beat them in columns!”46 There is an apparent contradiction here between the use of columns or lines that is easily explained. Suvorov used both. This again goes back to his transition between operational maneuver and grand tactical employment for battle, usually a meeting engagement. His purpose was to maintain the impetus of his attack on a broad front while maintaining the advantage in movement and cohesion provided by the column. As we shall see, this operational method was to work quite well with the Austrians, in fact they may have executed it more skillfully than their Russian comrades who often did not form line but remained in column for the duration of an attack.47

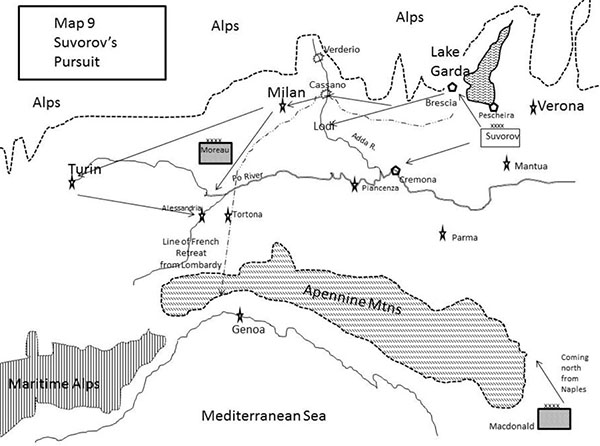

Map 9 Suvorov’s Pursuit

Suvorov conducted training courses to ensure the Austrians digested his instructions properly. This action could not help but have some negative consequences. The future Field Marshal Joseph Radetzky wrote of these instructions: “the order…was dictated to a victorious and confident army…The consequence was an extraordinary division between the allied forces—a division which extended all the way up to headquarters.” Not all of the Austrian officers were so alienated and Radetzky, chief of staff to General Michael Frederich Melas, Suvorov’s second in command and commander of the Austrian component of Suvorov’s force, may have simply been reflecting the views of his chief.48 Chasteler, in particular, made heroic efforts to work with Suvorov. He and the Cossack leader Denisov established a “joint” intelligence cell that combined Austrians, Cossacks, and Italians together to interpret the crude maps that the Cossacks made to describe their reconnaissance efforts.49

These affronts were initially mitigated by Suvorov’s victorious advance across Italy (see map 9). Suvorov maintained generally good relations with his Austrian staff and wore an Austrian rather than a Russian uniform to emphasize his spirit of cooperation.50 Suvorov’s intent was to give the French no time to recover and to liberate Lombardy while preventing Macdonald from joining up with Scherer (still in command for a few more days). Leaving Kray to prosecute the sieges of Peschiera and Mantua, he advanced northwestward and along the right bank of the Po with about 50,000 Austrians and Russians. First to fall, with its entire garrison (1,130), was Brescia on April 21 after a brisk bombardment and a threat to put the entire garrison to the sword if they did not surrender. To the south, an Austrian detachment advanced on Cremona, which was seized on April 22.51

It was during this hectic time that Moreau replaced in command of the shrinking French army. At Lecco, General Serurier repulsed the northern arm of Suvorov’s assault on the Adda; however, Moreau was defeated in a series of engagements around Cassano on April 26–27 as Suvorov forced the Adda River line, including, ironically, a barely contested crossing at Lodi, even though the French had destroyed the bridge there. Suvorov then turned his forces north against Serurier, who had not fallen back after the defeats around Cassano. At a bend in the Adda River near Verderio he was surrounded and had to surrender himself and most of his division (now down to about 3,000 troops). Suvorov’s energy and use of multiple lines of advance for his divisions had accomplished the first goal Emperor Francis had set for him—the arrival of the joint army on the western side of the Adda.52

Suvorov then set out, in disobedience of his orders, to capture Milan, capital of Lombardy. During this advance the Austrians seem to have executed Suvorov’s guidance faithfully. At St. Juliano a joint Austro-Russian division executed the double-line echelon tactic in an attack that blunted a counterattack by Moreau.53 Milan fell on April 29 and Suvorov forced Moreau into defensive positions in the mountains around Genoa, almost precisely the same location that Bonaparte had started from three years earlier. Suvorov’s offensive equaled that of the Corsican in energy, brilliance, and execution. Northern Italy now lay uncovered and the Allies settled into a consolidation of their gains by placing all of the major fortresses with French garrisons under siege. Suvorov additionally invaded Piedmont, reaching Turin on May 27 and putting that place, Tortona, and Alessandria all under siege.54 As usual, the French left too much of their combat power cut off and besieged. However, Suvorov would soon find his operations challenged as a new French army composed of undefeated veterans under a determined general rushed north to confront him.

OPERATIONS AROUND ZURICH AND THE TREBBIA

Suvorov’s operations had a profound effect on those of Masséna. Until this time Masséna had been holding his own, but the collapse of the French forces guarding his southern flank meant that he had to pull back. Initially, he had hoped to stabilize his front from Zurich to the left bank of the Rhine to account for the defeat of the French Forces in Germany. Because of the collapse of Scherer’s forces and the subsequent loss of Lombardy, Masséna received orders to send over 15,000 reinforcements south to help stabilize the situation on May 6. Nonetheless, he attempted to hold his position around Zurich.55

Archduke Charles gave Masséna no chance to rest. Advancing from the east he assaulted the French positions in front of Zurich on June 3 and was bloodily repulsed. When he returned on June 4 for another round of assaults, Masséna again skillfully drove the Austrians back, but his own Helvetian army had also suffered grievously. Rather than lose his entire army to a third Austrian assault, Masséna conducted a skillful retreat to a more defensible terrain to his west along the Limmat River and the Albis Mountains (see map 10). Masséna’s defensive victory at Zurich in June 1799 reminds one of the Duke of Wellington’s victory in Portugal at Busaco in 1810 against Masséna himself (see chapter 7). In both cases, a fine defensive victory was followed by an operational retreat to a more advantageous terrain—a superb example of defensive, attritional warfare in the hopes of one’s enemy making a mistake and creating the opportunity for a counterstroke. Masséna’s new position also provided better protection for his southern flank, which had been uncovered by the conquest of Lombardy and the threat now posed by Suvorov to Piedmont. At the same time, Masséna’s army was renamed the Army of the Danube and his command limited to Switzerland as a new Army of the Rhine was formed from the forces holding along that river north of Basel. Masséna also received reinforcements directly from France equating to a division of infantry and a brigade of cavalry.56

The Directory, hoping to retrieve the situation in Italy and relieve the besieged fortresses, recalled General Macdonald and his Army of Naples from southern Italy in order to unite with the remnants of Moreau’s army. Suvorov had, to a degree, anticipated this move and his requests for reinforcements brought 11,000 more Russians detached from Rimsky-Korsakov’s corps (on its way to Switzerland) and another 10,000 Austrians under Bellegarde from Charles’s army in Switzerland. Suvorov also suspended the siege of Mantua and detached Kray, the victor of Magnano, to the south to delay and develop Macdonald’s force as it advanced rapidly through Tuscany. Despite these Russian precautions, Macdonald and Moreau almost succeeded in uniting. Macdonald’s unexpectedly rapid advance to the Trebbia River took even Suvorov by surprise. Suvorov was not used to his enemies advancing as rapidly as he! Moreau’s job was to bring his now reinforced army into a position on Suvorov’s right flank where he could either threaten Suvorov or unite with Macdonald, or both.

Map 10 Masséna and Suvorov in Switzerland

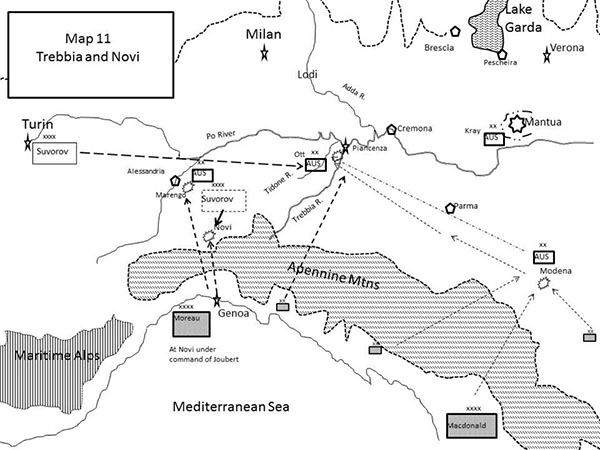

While Suvorov rushed with all available troops toward Tuscany (marching almost as far and certainly as fast as the French), Macdonald resumed his advance with an army of approximately 33,000 veteran troops. On the June 11, 1799, Macdonald collided with the advanced units of Austrians (General Ott’s division) at Modena (see map 11). The Austrians again used Suvorov’s tactics to good effect, this time bayonets against cavalry, and repulsed the French, although they lost part of their rearguard as prisoners to the French.57 As one reads these accounts of Russian tactics and bayonet charges one almost forgets that the troops doing the executing were Austrian. Macdonald advanced again on June 12 with more success and forced the Austrians in the center to retire on Mantua. Macdonald now turned to the northwest and the expected union with Moreau. The only force standing between the two French generals were the 6,000 Austrians under General Ott—but Suvorov, with 22,000 troops, was rushing to Ott’s aid. Additional Austrian forces under Melas were following in Suvorov’s wake. Macdonald had already pushed the retreating Ott over the Trebbia and halted between that river and the smaller Tidone River. The Trebbia was to be an engagement that exactly conformed to Suvorov’s style, a meeting engagement that grew over a number of days as new echelons arrived in the hope of shattering the French army and driving it away from Moreau.

The battle of the Trebbia began on June 17 as a skirmish by one of Macdonald’s divisions (Rusca’s) as it pushed across the Tidone. Ott’s Austrians were slowly withdrawing under this pressure when Suvorov and his advance guard, mostly Cossacks, arrived and counterattacked. The French, who had not expected a battle, were thrown back in disorder to the Trebbia with some units remaining on the western side. Macdonald claimed he had specifically ordered an avoidance of a battle until Moreau was in communication.58 The battle of the Trebbia, which started out as a meeting engagement between an advance guard and a rearguard, turned into a three-day battle of wills between Suvorov and Macdonald. In this it reminds one greatly of the Battle of Gettysburg during the American Civil War.

Map 11 Trebbia and Novi

Macdonald resolved to remain on the defensive to await the arrival of the rest of his forces. Suvorov, on the other hand, formed his army for the attack during the night as his tired troops marched up to the battlefield. Suvorov was not able to organize his forces and bring them up until the next afternoon. In doing so, he achieved a certain amount of surprise against the French on the left bank of the river. Macdonald withdrew Salm’s French division in haste and with loss to the right bank. The battle then raged into the night, the cannon only ceasing their racket at about 11 o’clock. Macdonald described the Austro-Russian attack as a “vigorous onslaught…their strength was great, and their cries and howls would have sufficed to terrify any troops except French ones.”59

Suvorov’s approach on the second day had been to advance in five large columns, which he again directed to “form line immediately in an orderly fashion…without pedantry or…excessive…exactitude [emphasis mine].” Macdonald counterattacked each of these columns in turn and nearly succeeded in forcing the Russians back. The Russian soldiers’ refusal to break after these punishing blows sustained Suvorov’s position on the west bank of the Trebbia as night and exhaustion brought the second day’s battle to a close. Suvorov’s decision to attack with his outnumbered and exhausted army had paid off—for the moment.60

The next day, both commanders decided to attack. Macdonald temporarily had the advantage in numbers and concentrated 12,000 of his troops for a decisive flank attack against the Russians under Peter Bagration on Suvorov’s extreme right. Macdonald supported the main effort by another turning movement on the left. These troops included the Polish Legion under Dombrowski, which had fought furiously against Suvorov the previous day. A Russian counterattack practically annihilated the Poles, but this attack in turn opened a gap around Suvorov’s central division under Schveikovsky. In turn, this gap permitted an opportune counterstroke by Generals Victor and Rusca that almost broke the back of the Russian position. The crisis of that day’s battle had arrived. Both Bagration and Rosenberg requested to withdraw. At this point, Suvorov became personally involved in animating his troops. Macdonald heard that Suvorov went so far as to threaten to kill himself if his troops withdrew another step. Melas, the senior Austrian general present, exacerbated the crisis by bringing only part of the reserve into the bloody melee in the center. However, the Russians held and the third day’s battle died down with both sides still separated by the river. Macdonald and his surviving subordinates had had enough. After a council of war they withdrew under the cover of darkness with their campfires still burning and retreated through the mountains to the west, toward Genoa. When Macdonald arrived there, he and Victor were summoned to Paris to explain themselves.61

When the Cossacks advanced early the next morning they found the French gone and Suvorov ordered an immediate pursuit. What little pursuit he was able to mount managed to capture the bulk of Macdonald’s rearguard, thus demonstrating how even the most meager pursuit by reserves can deliver great rewards. Macdonald acknowledged that he had received “disastrous…losses” and estimated the Allied casualties as equally “enormous.” The butcher’s bill was sobering: including the rearguard actions, Macdonald had lost half his army, some 16,000 killed, wounded, and prisoners. The Allied losses, for the size of their army were nearly as bad, 6,000 killed and wounded Russians and approximately 4,000 to 5,000 Austrians. Meanwhile, Moreau’s advance near Marengo had cost the Austro-Russians another 2,000 casualties due to an abortive counterattack by General Bellegarde. It is clear that Moreau’s sluggishness in coming to MacDonald’s aid, despite his success near Marengo, probably cost the French the battle.62

Operationally, the Battle of the Trebbia highlighted for both sides the importance of rapid maneuver over long distance and then fixing one’s enemy by feeding reserves into the battle as they arrived. Suvorov’s goal was always to prevent a juncture of the two French armies and his skill in doing so reminds one of Bonaparte’s actions at Castiglione and around Mantua. The French lost at least twice as many casualties (not including their rearguard) as the Austro-Russian army, a clear testament to the training and combat power of both the Russians and Austrians against a veteran, well-led French army.

A final note on the battle of the Trebbia concerns the actions of General Melas. The Austrians had already been campaigning longer and, to a certain extent, were fatigued. But the Russians were also spent after their numerous forced marches. One historian has noted that it was “curious” how slow and ineffective Melas was in supporting Suvorov on both June 18 and 19. All accounts of the battle agree that Melas responded slowly. Even Macdonald admits that had he been hard-pressed on the second day (June 18) he did not know what he should have done.

Rather than improve the unity of effort of the coalition, the conduct and results of this bloody battle combined with other negative trends to undermine the unity of the coalition in this theater. In May, prior to the Trebbia battle, some of the Austrian generals “complained about Suvorov’s crude tactics and unnecessary losses and risks (emphasis mine).”63 Suvorov had already lost his excellent chief of staff Chasteler due to Austrians who schemed against that officer simply because of his devotion to Suvorov. Colonel Weyrother, Chasteler’s replacement, became just as devoted to Suvorov, but this move indicates trouble in the coalition ranks was starting to have a negative influence.64 Was Melas in fact one of the officers that had been complaining about casualty rates and did he rectify the situation locally during the battle by dragging his feet? No solid proof exists, but the “curious” nature of his actions argues that he may have.65 Up to this point, Thugut had generally backed Suvorov against complaints by Austrian generals, despite the fact that Suvorov’s high casualties, particularly among his Austrians, ran counter to the “first priority” of the Habsburg dynasty—the preservation of its army. Suvorov had already alarmed Thugut by calling on the Piedmontese to rise up and support their exiled king, which was contrary to current Austrian policy of absorbing Piedmont in some fashion after the successful conclusion of the campaign. Immediately after the battle Suvorov received word that Turin (Piedmont’s capital) had surrendered. Suvorov, following the Tsar’s orders, used this event as an opportunity to summon the Piedmontese king from Sardinia to resume the throne. Thugut immediately disavowed Suvorov’s actions and subordinated him to his personal control.

Suvorov’s Austrian subordinates now began to speak openly against him. Thugut no longer discouraged their bypassing Suvorov to communicate directly with him. Additionally, Suvorov was now required to report to Vienna prior to engaging in battle. Prior to leaving for Italy Suvorov had written the Tsar a confidential note stating his intention not to “waste time in sieges.” The simmering debate over strategy and the operational means to inform it—sieges versus field engagements—was now resolved in Austria’s favor. The Austrian strategy involved a reduction of the remaining fortresses in Italy before resuming field operations against the French. The losses during the Trebbia fight had gutted Suvorov’s Russian contingent and he was now very dependent on the Austrians to conduct the sieges and for replacements. In this manner, not out of deference to Thugut but because his control of resources was limited to his Russians, Suvorov had to submit or resign. Paul rejected any suggestion that Suvorov be replaced. These internecine squabbles, as already discussed, became a major factor in all parties desiring to move Suvorov to another theater.66

The course of the campaign during July now assumed a slower pace as Suvorov bowed to the will of Thugut and the Hofkriegsrat. General Moreau was masked in Genoa while the sieges of Mantua, Tortona, and Alessandria continued. The French had other plans. They now sent General Joubert, one of the stars of Napoleon’s first Italian campaign, to take command from Moreau, who was to move north to command the Army of the Rhine. Joubert’s mission was a component of a broad scheme of French counteroffensives running from southern Germany to Italy. Joubert was reinforced to a total of approximately 40,000 troops, which gave him a field force of approximately 35,000 troops.67 His goal was the relief of the beleaguered French garrison of Mantua. Joubert wisely retained Moreau for the time being as an adviser for the upcoming offensive.

Mantua, however, had surrendered on July 27 and Alessandria even earlier on July 21. These surrenders released considerable Austrian reserves for operational use, especially Kray’s outsized division (almost a corps) from Mantua. Joubert was unaware of these facts as he advanced in four columns on August 11 toward the Po River valley from his bastions in the Maritime Alps. Suvorov, reinforced with 10,000 more Russians (diverted from Korsakov), now rushed to engage Joubert with over 51,000 troops in hand. He also issued orders for his screen troops not to impede the French advance so that he could “lure the French down from the mountains to the plain and crush them.”68 Again, Suvorov’s operational design was a meeting engagement with the unready French columns to be followed by echelon after echelon arriving over time until his enemy was overwhelmed. As usual his Russians and Cossacks would lead the way. On August 14, Joubert’s divisions united at Novi and halted. Suvorov’s army, with the exception of Melas’s column, had also arrived before Novi. Joubert, surprised by the size of Suvorov’s force, which was larger than his own, now contemplated retreat. While Joubert hesitated, Suvorov attacked.

Joubert’s defensive position had its left flank firmly anchored in the Maritime Alps at Pasturana with strong defensive positions in the center around Novi. Joubert’s right was weak and “in the air,” but it seemed safe because Melas was still distant and Joubert was unaware of his approach. Suvorov’s conduct of the battle was simple. He intended to fix the French with heavy attacks on their left, then their center. As these attacks proceeded, he would deliver a flanking blow using Melas against the French right. Finally, he used wider flanking movements, one composed of a cavalry force and another Russian contingent under Rosenberg, to maneuver on the French rear. The Austrian general Kray “begged” Suvorov for the honor of opening the attack on the French left with his corps. Of note, Suvorov was routinely organizing his army into multidivision corps, sometimes even combining Austrian forces with Russians—predating to some extent the formalization of the corps as an operational organization by the French under Napoleon.

The attack began at daybreak, the first of 10 attacks by Kray that day.69 It caught Joubert off-guard and he was killed as he reconnoitered forward of Pasturana with his skirmishers. Moreau, confirming Joubert’s wisdom in retaining him, took charge and another contest of wills began as Suvorov attempted to pry Moreau out of his defensive positions. Success depended on Melas, who had been so slow at the Trebbia. He did not disappoint his Russian commander on this day. The battle was nine hours old when Melas arrived and opened his attack on the French right, which Moreau had weakened to support the vicious attacks on his left and center. Melas’s actions, along with the deep penetration near the French rear by the other two columns, convinced Moreau that his position was untenable and he attempted to withdraw. Moreau’s artillery became entangled in the narrow village streets and mountain roads, blocking and disordering the retreat. Many of his troops were taken prisoner.70

The price paid for this success was severe losses incurred by Kray’s Austrians and Bagration’s Russians. The final result was nearly 12,000 French casualties (4,000 of them prisoners) as opposed to almost 8,000 for the allies—the greater percentage of them Austrian. One historian has claimed that “Even at the Trebbia the fighting had not been so inhumanly bitter and obstinate as it was here.”71 The last French field force in Italy had been defeated and would soon be confined within Genoa for an epic siege. It was ironic that the battle of Novi, where cooperation between Russians and Austrians on the field of battle was never exceeded again in that generation, stood in stark contrast to the squabbling, distrust, and outright enmity that existed between the governments represented by Suvorov’s army. However, the cost in Austrian lives was enormous by 18th-century standards.

The fragile unity of effort that still existed in the field was soon to collapse at higher levels due to three factors: (1) the strategic shift of Suvorov to the north, (2) the dispute over the issue of sieges versus an annihilating pursuit and expulsion of the French from Italy, and (3) the cumulative heavy losses to the Austrian army in all theaters, but especially Italy. A week after Novi, Suvorov finally received official orders for his transfer, with his Russian troops, to Switzerland. He was opposed to this move because “with the loss of Italy, one cannot win Switzerland.” However, Suvorov’s disputes with the Hofkriegsrat, which had ordered him to cease his pursuit of Moreau, finally convinced him to observe, “I cannot continue to serve here.”72 Suvorov’s problems with his subordinates only worsened. Melas resumed his hostile attitude and refused to obey Suvorov’s orders if they did not correspond with the orders he now received from Vienna. Although Suvorov had won the decisive battle of the Italian campaign, the Austrians no longer felt the need for his services in Italy. Baron Thugut’s correspondence reveals the prevailing Austrian attitude toward Suvorov at this juncture:

The innumerable inconveniences caused in Italy by the conduct of this general [italics mine], acting according to foreign [Russian] orders and obviously opposed to the interest of His Majesty, are of such a grave nature that His Majesty could easily do without his commanding an army [in Italy] if having him sent to Switzerland is happily followed.73

The Austrian generals were no longer answerable to Suvorov, unless, like Kray and Chasteler, they risked their standing with Vienna by cooperating with him. This should have been no surprise to the old field marshal. Under Austrian officers the casualties would certainly have been less, although the results perhaps less decisive.74

MASSÉNA AND SUVOROV IN SWITZERLAND

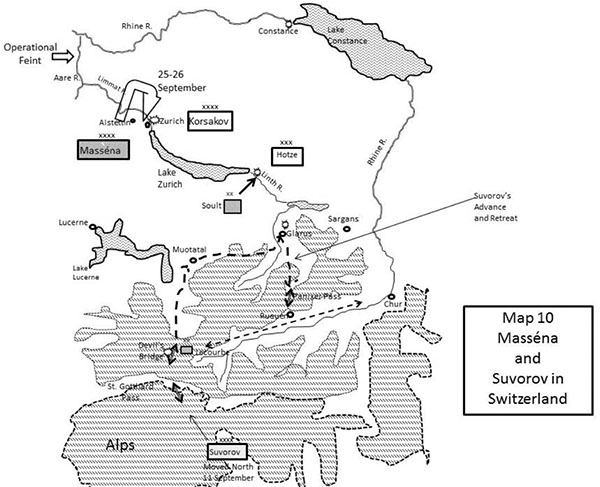

It is fitting that the closing chapter of the War of the Second Coalition in 1799 should bring into conflict the two operational artists we have been following: Masséna and Suvorov. Before bringing them together, though, we must return to the period prior to the Battle of Novi, as Masséna slowly improved his operational position in Switzerland and then created his own masterpiece around Zurich. Recall that by late June Masséna had stabilized his position east of Zurich along the Aare and Limmat Rivers. In the southern portion of his theater, an independent division of 12,000 troops under General Jacques Lecourbe operated east of Lucerne (see map 10). Masséna made successful probing attacks to the east at Alstettin and Lecourbe probed toward the critical St. Gotthard Pass by which Suvorov would have to come north with his Russians once he left Italy after the battle of Novi.75

By August, Masséna was ready for more than tentative measures and had Lecourbe move directly against the St. Gotthard Pass, guarded by one Austrian brigade. Lecourbe, as much an expert in mountain warfare as Masséna, seized the critical pass on August 18. Masséna had his forces, principally the divisions of Generals Soult and Lorges, demonstrate on the Limmat to distract Charles.76 Charles naturally assumed that offensives before Zurich and in the south must mean the French left was weak and he attempted to throw a bridge across the Aare River on August 17, but this attempt was handily defeated by light artillery and Swiss riflemen from Masséna’s reserves. Finally, other French forces further secured Masséna’s right flank against the Austrians by capturing the town of Glarus to his southeast on August 29.77

It was at this point—with Masséna reinforced to a strength of over 87,000 men, a field force of about 40,000 under his direct command west of Zurich, and much good ground in his possession for further offensive operations—that the Allies ordered Charles north for operations in Germany and Suvorov north to combine with General Rimsky-Korsakov’s newly arrived corps in Switzerland. Charles received his order to depart with the bulk of his Austrians the day after his repulse on the Aare River (August 17) and Suvorov received his own orders to depart Italy with his Russians a week after Novi. Charles had protested this plan but duly executed his orders due to his new focus for operations being much further north along the Rhine near Mannheim. Masséna was presented with a golden opportunity to retake Zurich and destroy Korsakov’s army before Suvorov or Charles could come to his aid.78

As August came to an end, Masséna found to his front approximately 48,000 Russians and Austrians with Korsakov covering the front from the Rhine to Zurich and about 24,000 Austrians under General Hotze covering the northern shore of Lake Zurich and the Linth River.79 It was against this extended front that Masséna now massed. To the south, Lecourbe was directed to continue his own offensive toward the Grisons against the strung out forces of Hotze, leaving only light forces covering the St. Gotthard Pass. Suvorov approached this pass with over 21,000 of his Russians and an Austrian brigade under Auffenberg assigned to join his command once he forced the St. Gotthard Pass.80

Masséna had all the advantages of interior operational lines during this delicate period, but he had to act before Suvorov erupted from the St. Gotthard Pass on his flank and into Lecourbe’s rear. General Bernadotte, the new war minister for the Directory, informed Masséna of this opportunity on September 5 after Masséna reported Charles’s departure. By September 20, Masséna had resolved to attack in three different places: with his main army against Korsakov at Zurich, using the division of Soult against Hotze on the Linth, and with Lecourbe, as already mentioned, toward the Grisons. His main effort at Zurich involved an operational deception against the widely deployed Russians on their right flank near the Rhine, to distract their attention, while he sent a column of 14,000 men over the Limmat toward Zurich. At Zurich he employed tactical deception by stealthily moving cannon and bridging elements directly opposite the city. The second Battle of Zurich began on September 25 with these cannon waking up Korsakov and his troops in the city, achieving both operational and tactical surprise. The crossing of the Limmat occurred without opposition as Korsakov focused on the forces immediately to his front. The key to the battle was the seizure of the Zurichberg high ground and this Masséna’s main column did at great cost while at the same time it seized the western suburbs. By the end of the day the French had trapped Korsakov inside the city, where Masséna offered the Russian the opportunity to evacuate the town without further bloodshed. Meanwhile, to the south, Soult had also achieved tactical surprise in crossing the Linth and eliminating any possibility of Hotze’s Austrians coming to Korsakov’s aid. The brave Hotze was killed at the beginning of this engagement.81

Korsakov, learning of Hotze’s death and Soult’s success, refused Masséna’s offer and resolved that night to retake both the suburbs and the Zurichberg while he broke out with the rest of his army to the north (probably to save his many cannon). These attacks were initially successful, gaining Korsakov some time, but ultimately they resulted in many more losses as the French counterattacked and slaughtered the packed Russians as they retreated through the streets of the city. Korsakov had lost over one-third of his army, 9,000 troops, including over 5,000 prisoners. The losses of the Austrians to the south were also heavy. On October 7, Korsakov lost another 3,700 men in an ill-advised attempt to regain some of the initiative when he attacked the far left of the French line along the Rhine. After that his force was no longer capable of offensive operations. At the other end of the wavering Allied line in the north, held by the émigré corps of the Prince of Condé at Lake Constance, Masséna continued his operations, taking Constance on October 8.82

In the south, Masséna gave the Austrians no rest, attacking with Soult who managed to link up with Lecourbe, inflicting over 5,000 casualties and causing the leaderless Austrians to retreat. But now it was the French turn to go on the defensive as Suvorov’s army entered the theater of operations, sweeping away the French forces at the St. Gotthard Pass and then driving hard for the next mountain defile at the famous “Devil’s Bridge.” Here, by sheer willpower and with much loss, Suvorov forced an almost impassable defensive position against Lecourbe’s troops and artillery. As Lecourbe fell back he was joined in the nick of time by Soult coming down to reinforce him. Together these two divisions repulsed Suvorov’s advance guard. It was at this time, on September 28 that Suvorov learned of Korsakov’s disaster and realized his army was probably Masséna’s next meal.83

Suvorov began to retreat toward Glarus to cross the Linth River. He did so knowing that he was essentially bottled up in an alpine pass with French and Swiss forces to his front and even larger French forces in his rear. Nonetheless, he battled his way through the forces between him and Glarus, arriving at that town early on October 1. For the rest of the day his advance guard fought a desperate action against superior French forces on the Linth north of Glarus, but the French repulsed a series of uncoordinated and furious Russian assaults across the river. The way north was seemingly barred by strong French forces. By October 4, his rear corps under Rosenberg had closed up after an exhausting march from Muotatal. For one of the few times in his career Suvorov made a poor decision. Influenced by the Tsar’s relative Prince Constantine, who accompanied the army, Suvorov accepted a majority decision of a council of war on October 2–3 to reject another try (proposed by Weyrother) along the northern line of retreat toward the Austrians at Sargans. This was what Archduke Charles hoped he might do and he pushed more troops in that direction to join with Suvorov once he punched through the French. However, Suvorov decided to retreat over the Alps through the almost impassable Panixer Pass, which meant he would have to abandon his artillery since only pack animals could make it through that route. It is hard to say what might have happened had Suvorov followed the advice of Weyrother and Archduke Charles. Condé’s defeat at Constance on October 8 might still have made the northern route untenable given the success of French arms. However, the Russian generals under his command no longer trusted the Austrians and the route to the south was chosen. Suvorov abandoned his cannon, wounded soldiers, and trains and set off.84

The southern route proved perilous enough. Suvorov was racing against time as Masséna had four French columns closing in on him: Gazan’s division to his north, Molitor’s division to his west, Loison’s division to his south, and another wide flanking column of one battalion to his east. The most dangerous column was that of Loison, which if it could reach the southern end of the Panixer Pass would have an overwhelming advantage in numbers and artillery that Suvorov probably could not overcome as two more French divisions closed on his rear. Suvorov won this race, but at great cost as his men collapsed in the deep snows and high altitude and were left to die or be taken prisoner. On October 8, when his men crawled into Rueuen on the Vorderrhein River, the force of over 21,000 Russians numbered no more than 11,000 effectives, the Cossacks, amazingly, having fared best.85

Masséna and Suvorov had not actually fought within eyesight of each other in this final operational match, but that is the way of operational art, one’s combinations are often unseen and frequently dependent on the initiative and leadership of operational subordinates. Masséna can be said to have defeated Suvorov at Zurich, even if he did not defeat him in person during the harrowing Russian operations in the heart of the Swiss Alps. Masséna went on to earn the sobriquet of “Dear Child of Victory” and the acclaim of the Republic while Suvorov received orders to return to Russia with his army and was dismissed in disgrace by an ungrateful Tsar. The old Russian died, heartbroken it is said, not long after in 1800.

In conclusion, the collapse of the Second Coalition was due to many factors, not the least of which were the divergent war aims of Austria, Russia, and Great Britain. Nonetheless, Suvorov’s handling of the Austro-Russian army in 1799 in Italy strained an already fragile unity of effort. Suvorov saw the fine instrument that he had in the Austrian infantry and used it to maximum advantage. The Austrians performed, in many respects as well or better than their Russian comrades, whose very nature dictated the tactics that Suvorov employed. In the process Suvorov damaged this instrument with excessive casualties. More importantly, it was never “his instrument” to begin with, it was only on loan. He may have better served his cause to have understood the constraints for its use before decimating it in two bloody battles. The wastage of Austrian troops since the war’s beginning in March, a scant five months earlier, now numbered more than 100,000. The Habsburg dynasty could ill afford to continue these bloody campaigns and hope to have an army to control their empire, much less fend off the Turks, Prussians, and even Russians.86 The Austrian decision to let the Russians assume the main offensive burden at the end of the summer of 1799—in the light of all this evidence—is not surprising. It was not so much the French who defeated Suvorov as it was the disunity and strategic combinations of the political leaders of the Second Coalition. In the final analysis, Suvorov practiced operational art to a high degree in Italy and Switzerland, but he did not practice it successfully within the framework of coalition warfare. Thomas Graham’s contemporary comment at the end of his narrative of this campaign sums it up: “[Suvorov] was the best possible General for the Russians [emphasis mine].”87