NAPOLEONIC TOTAL WAR IN SPAIN AND RUSSIA

1810–1812

CHRONOLOGY

| Nov 19, 1809 | Marshal Soult destroyed Spain’s largest organized army at Ocana. |

| Jan–Feb 1810 | Soult conquered Spanish province of Andalusia. |

| Apr 17 | Napoleon appointed Marshal Masséna as commander of the Army of Portugal. |

| Jun 10 | Masséna captured Spanish fortress of Ciudad Rodrigo |

| Aug 27 | Masséna captured Portuguese fortress of Almeida |

| Sep 27 | Wellington defeated Masséna at Bussaco and fell back into Lines of Torres Vedras |

| Dec | Russia accepted British goods into its ports and secretly prepared for war with France. |

| Mar 1811 | Masséna’s army, famished for lack of supplies, retreated from Portugal. |

| Mar 10 | Soult captured Spanish fortress of Badajoz. |

| May 3–5 | Wellington defeated Masséna at Fuentes de Oñoro. |

| May 11 | Wellington captured Almeida. |

| May 16 | Beresford defeated Soult at Albuera near Badajoz. |

| Jan 19, 1812 | Wellington captured Ciudad Rodrigo. |

| Apr 6–7 | Wellington captured Badajoz |

| Jun 23–25 | Napoleon crossed the Niemen River and invaded Russia. |

| Size of French main army group became approximately 380,000. | |

| Jul 22 | Battle of Salamanca, Wellington defeated Marmont and Soult withdrew from southern Spain. |

| Jul 28 | Napoleon was at Vitebsk. |

| Size of French main army group became approximately 200,000. | |

| Aug 12 | Wellington liberated Madrid. |

| Aug 15–19 | Battles near Smolensk, Russian armies united to defend Moscow. |

| Size of French main army group became approximately 150,000. | |

| Sep 7 | Battle of Borodino, Russians under Kutusov withdrew and abandoned Moscow. |

| Sep 14 | French entered Moscow. |

| Size of French main army group became 95,000. | |

| Oct 18 | Napoleon’s Grande Armée began retreat from Moscow. |

| Nov 25–29 | Napoleon crossed the Beresina. |

| Size of French main army group (including stragglers) became approximately 40,000. | |

| Dec 15 | Size of the remnant of French main army group, including stragglers and reinforcements became approximately 12,500. |

Nations in arms, army groups, combined arms organization, tactics at all echelons, and massive fire power—by the end of 1809 all these things were in place on “both sides of the aisle” during the Napoleonic Wars. However, this study contends that, despite 17 years of nonstop conflict, Napoleonic warfare only became “total war” in 1810. Certainly, total war in the sense we use it today includes all the factors mentioned in the first sentence.1 Allied strategists and generals unknowingly applied Hans Delbrück’s strategies of attrition, using protracted conflict to wear their enemies down—in this case Napoleon and his French-led armies. Wellington had already outlined such a strategy before returning to Spain. In 1810, with a massive invasion of Portugal looming, he put into place the operational framework for protracted attritional warfare, policies, and actions, which may be termed absolute or total, by his troops in concert with irregular forces. Consistent with Delbrück, and reflecting the wisdom of Clausewitz that weaker powers must take advantage of the defense as the stronger form of war, Wellington showed the way in his 1810–1811 campaign in Portugal by using combat power, not for the offensive, but for the strategic and operational defensive as a means to sap the strength of an army of potentially 100,000 men invading Portugal.

Similarly, when Napoleon made his disastrous decision to invade Russia and solve the problem to his east once and for all, the Russians, less deliberately, stumbled into the power of the strategic defense as a means of exhausting the enemy. In both of these hellish campaigns—Portugal and Russia—geography played an immense role in the operational framework. But they shared these commonalties of defense, protracted resistance and retreat with a goal of “erosion,” as Wellington named it, of the adversaries’ larger forces. In both campaigns, the key for the operational artists involved—Wellington, Marshal Kutusov, and the less-known Tsarist generals Barclay de Tolly and Peter Bagration—centered on the Clausewitzian concept of the “culminating point of victory” that “turning point at which attack becomes defense.” In On War, Clausewitz went further, undoubtedly using his personal observations of the 1812 Russian campaign to declare: “It is the defense itself that weakens the attack. Far from this being idle sophistry, we consider it to be the greatest disadvantage of the attack that one is eventually left in a most awkward defensive position.”2 Using operational art, Wellington and the Russians managed to engineer precisely this “awkward defensive position” in front of the lines of Torres Vedras in Portugal in 1810–1811 and Russia at Moscow in 1812.

Although they were not total war, in the modern sense that sees the phenomenon inherently related to technology, these campaigns emphasize the bedrock of human, political, strategic, and geographical components of total war. They constitute a reflection of the concept as all-out war, on the largest possible scale, and to the bitter end of exhaustion and defeat, for one side or the other. Such was World War I, whose 100th anniversary is now upon us. So also were these campaigns over 200 years ago.

* * *

Napoleon seemingly triumphed in 1809—both in Spain and against Austria. Yet, Great Britain remained at war while the Napoleonic system in Europe and a cruel compound war in Spain and Portugal simmered on. The Napoleonic system still had some triumphs left to it in Spain, but not against Lord Wellington. Wellington grimly committed himself to a strategic defensive, ignoring the pleas of his Spanish allies to join them in yet another round of fruitless offensives against the French forces occupying the key central position in Spain. His experiences in the unsatisfactory Talavera campaign and the defeat of the Austrians at Wagram convinced him of this necessity and he advised his Allies to remain on the defensive and husband their strength. He withdrew to Abrantes in Portugal to prepare for an invasion army that might have Napoleon at its head. The British polity also influenced Wellington’s decision for the defense, as opposition politicians proposed in 1809 and again in 1810 to withdraw Britain’s one field army from the Peninsula given the threat posed to it and the apparent French victory in Spain. By not risking his army in any further offensive adventures, Wellington managed to maintain its presence in Portugal for the time being.3

The Spanish pressed on without him and pushed an army of 50,000 men north from Andalusia in an attempt to retake Madrid. This army initially advanced rapidly, catching the French dispersed, but then balked along the Tagus River. Marshal Soult, in overall command, concentrated his forces and destroyed the Spanish army at Ocana on November 19. Napoleon, who had planned to come south of the Pyrenees, now became distracted by his divorce from Empress Josephine and subsequent marriage to Austrian Princess Marie Louise. These distractions provide further evidence of the decline in his political and military judgment. He left Spain to his subordinates as he pursued his dream of having a legitimate heir to his throne. King Joseph and Marshal Soult decided to take advantage of their victory at Ocana and press ahead during the winter of 1810 by conquering Andalusia, scene of the disaster at Baylen two years earlier (see map 21). In January–March, Soult moved south with over 70,000 troops in three corps. With the only effective Spanish army destroyed, he had little trouble taking Seville, causing the ruling Spanish Junta to flee to Cadiz. Soult followed and put this place under siege, but he, Joseph, and Napoleon—oblivious to the strategic mistakes being made in Spain—had now tied down 70,000 more troops to occupying a vast area of Spain without any positive result. The guerilla resistance continued. As a consolation of sorts, Soult captured the key fortress of Badajoz that dominated the southern invasion route into Portugal on March 10, 1811.4

By April, Napoleon had a new empress and had decided to leave the most important job in Spain, dealing with Wellington’s dangerous Anglo-Portuguese forces, to his most illustrious marshal. The emperor had recently named Andre Masséna Prince of Essling for his superb combat leadership at Aspern-Essling, leadership that probably saved the French army from disaster. Masséna was certainly the right man for the job in Spain; if anyone could defeat Wellington it was him. However, Soult was now tied down occupying and garrisoning vast areas of Estremadura (Badajoz) and Andalusia, and would be no help in the upcoming campaign. Nonetheless, Masséna had over 65,000 troops in three corps commanded by Ney, Junot, and the Swiss mercenary general Jean-Louise-Ebenezer Reynier. Masséna assumed command of his force in May at Vallodolid before moving up in June to oversee the reduction of the fortress of Ciudad Rodrigo. The siege of this place, along with the Portuguese fortress of Almeida, gobbled up much of the summer. Masséna’s forces had already been campaigning for two months before they pushed on toward Lisbon in earnest in early September. Napoleon’s attitude toward the challenge that Masséna faced was completely unrealistic, observing “It was absurd his armies should be held in check by 25,000 or 30,000 British troops.”5

Napoleon’s assessment of Masséna’s challenge must be examined against Wellington’s intricate plans for the defense of Portugal and an anticipated invasion by as many as 100,000 French troops. Thanks to Soult and King Joseph he would deal with considerably fewer than that. Also, thanks to these other Spanish adventures and Napoleon’s odd attention deficit when it came to the Anglo-British forces on his flank, Wellington had been given almost a year to prepare for the invasion. Wellington’s plan had four major components: creation of a suitable Portuguese regular army to augment the British; construction of a line of defenses from the broad Tagus to the Atlantic; training and equipping of the ancient Portuguese militia—the Ordenanza—for use against French communications to Spain; and, finally, the complete devastation and depopulation of the Portuguese countryside. This last served as a means to deny the French any ability to use their logistical practice of foraging their troops on the countryside and sequestering village stores.6

The first component, as we have already seen, was given over to Marshal Beresford, who by the time of Masséna’s invasion had trained over 30,000 Portuguese regulars, some with him in the south observing the southern invasion route, but most in the north integrated into Wellington’s field army of 50,000 facing Masséna. Wellington had already noted the defensive value of the terrain north of Lisbon, centering on the town of Torres Vedras. In October 1809, nine months before Masséna entered Portugal, the British commander had begun fortifying this ground, 30 miles in length from the ocean to the impassible (due to the Royal Navy) estuary of the Tagus River on a roughly northwest-southeast line. He judged that he could move much of the Portuguese population into this strategic redoubt, which reminds one of the defenses seen later on the Western Front in World War I. The line reflected a defense in-depth of three “belts” of fortifications with dozens of forts and many more redoubts, all covering various fields of fire with lateral roads along which Wellington could rush his mobile reserves to shore up the front. Eventually, these lines contained over 447 pieces of artillery.7

The last two components of Wellington’s defensive scheme were equally important, but aided by both the geography of Portugal and Masséna’s choices. First, Masséna and Napoleon had not made arrangements to secure the line of communication back into Spain, believing the countryside empty when in fact the Ordenanza could and did interdict these lines effectively. Any French formation smaller than a battalion or a squadron found it difficult to support itself against the well-armed, mobile irregular forces that Wellington and Beresford put into the field. Finally, Wellington’s chore in devastating the Portuguese countryside was made easy by the arid and unforgiving region through which Masséna invaded. Instead of advancing on the south bank of the Mondego River, where the roads were better and closer to more fertile regions, Masséna invaded along the north bank of the river valley, some of the most forbidding and inhospitable terrain in the country. Masséna described Wellington’s “scorched-earth” policy in a report to Berthier on his advance, “Sir, all our marches are across a desert. Not a soul to be seen anywhere; everything is abandoned.”8

Masséna had sidestepped Wellington’s plans for a prepared defense on the main road from Almeida to the interior of the country, but the Englishman reacted quickly, moving his forces opposite the French and conducting a delaying retreat until reaching a strong position at a ridge near Busaco (see map 21). Here, on September 27, Wellington fought another of his signature defensive battles—52,000 Anglo-Portuguese defeating 60,000 French and inflicting 5,000 losses on them for 1,500 Anglo-Portuguese lost.9 The steadiness of the new Portuguese troops proved a rude shock to Masséna; however, despite this defeat he outflanked Wellington’s position. Wellington, instead of risking another tactical action, simply retreated toward his elaborate defenses at Torres Vedras. On October 10, he had over 77,000 men manning these lines, including 8,000 Spanish regular troops from the Army of Estremadura and 11,000 armed and trained militia. Wellington reinforced the lines with about 20,000 men, keeping his main field army concentrated as an operational reserve behind the lines to react to any major attack that Masséna might attempt.10

Masséna followed Wellington, again through an almost entirely deserted landscape with little food. Then, in a scene that foretold similar disasters to come in Russia, Junot’s ill-disciplined corps arrived at Coimbra, the only major city until Lisbon on his route of march, and sacked it, reputedly destroying enough food and stores to have revictualed the entire French army and sustained it for weeks. Instead, the remainder of the French army continued on meager rations. Masséna did not yet know of the Lines of Torres Vedras and made the decision to try to catch Wellington’s army in its retreat to Lisbon and force a battle on better terms than at Busaco. Perhaps he could even hustle the British aboard their ships for a hasty evacuation of all of Lisbon as Soult had done at Coruna. Accordingly, he left 3,500 of his wounded and sick in Coimbra with only two companies to guard them. On October 7, a Portuguese militia division swept down and recaptured Coimbra with all of the wounded and sick as well as French supplies being gathered there. Shortly after Masséna learned his communications through Coimbra were cut, he discovered the nasty surprise of Wellington’s fortified defensive belt. His cavalry arrived before these positions on October 11 amidst the cold autumn rains and reported the fortifications. Masséna himself reached them on October 14. The old Marshal’s practiced eye informed him of the absolute strength of the position, all along its front, with the victors of Busaco waiting to administer another rebuff to his tired, hungry, and now cold troops. With the Royal Navy protecting its flanks, there was no way to outflank this position.11

Masséna had reached the culminating point of victory before Busaco—at Torres Vedras he was clearly beyond it. His troops were cut off, they could not go forward; but Masséna, whose strength of will had been severely tested in the past, was not inclined to retreat. The French had little in the way of supplies and were slowly starving while the Royal Navy supplied their adversaries by sea. In no other campaign did the British advantage in sea power and the French approach to logistics play as large an operational role. Masséna decided to encamp in front of the lines, hoping the British might attack him and give him a cheap victory. Wellington made no such error, relying on irregular forces, the strength of his works, and starvation to win him the victory. Now, with every day that passed, Masséna grew weaker. This lasted for almost a month before Masséna, to avoid the complete starvation of his army, pulled back up the Tagus to Santarem, where his army could forage and await reinforcements from Napoleon. It is a testimony to Masséna’s will that he made it through most of the winter encamped in Portugal, but his army was ruined. There was some hope that Soult, who had begun besieging Badajoz in January 1811, might advance on the southern front and link up with Masséna south of the Tagus. But Soult’s siege dragged on and by March 5 the Prince of Essling began his retreat back the way he had come toward the supplies and fortresses of Almeida and Ciudad Rodrigo. Five days later (March 10), Soult captured Badajoz.12

Foreshadowing his later performance in Russia, Marshal Ney commanded Masséna’s rearguard during the retreat, allowing the remnants of the once mighty army of Portugal to withdraw with some sort of order into Spain. Wellington followed close on his heels but failed to achieve any major victories given Ney’s tenacity and skill. Wellington was able to place Almeida under siege in April. The cost to French arms had been over 30,000 troops with the result that the British position was immeasurably stronger than it had been the year before. The French situation got no better. Napoleon’s relationship with Tsar Alexander had deteriorated to a point that he had already begun to withdraw his best soldiers from Spain, which at its peak contained 370,000 troops of the French and their allies. Wellington’s campaign had broken the back of the ability of the French to take the strategic offensive against the Anglo-Portuguese armies along the rugged Portuguese-Spanish frontier, as became clear in May 1811. That month saw both Masséna and Soult attempt limited counteroffensives to relieve sieges of Badajoz (by Beresford) and Almeida (by Wellington).13

Wellington again underestimated the operational durability of a French army. Masséna had restored some semblance of discipline after feeding and resting his tired troops (and gaining some replacements) at Ciudad Rodrigo. Early in May he advanced against the outnumbered Anglo-Portuguese army at Fuentes de Onoro with 48,000 men to Wellington’s 36,000, achieving both tactical and operational surprise. Although Masséna managed to flank his enemy’s position, Wellington again won on the defensive by “refusing” his right flank with some very skillful maneuvering. The victory was somewhat diminished when the garrison of Almeida escaped back to French lines on May 11. Despite this, Fuentes was Masséna’s swan song; he lost some 2,800 casualties to about 1,800 for Wellington. As his master was to learn in Russia, the old fox no longer had the youthful vigor for harsh campaigning that the war in the Peninsula required. Napoleon replaced him with the younger Marshal Auguste Marmont.14

In the south the Beresford attempted to recapture the critical fortress of Badajoz, which was absolutely necessary before even limited offensive operations could be conducted inside Spain. Here the result was less fortuitous. Soult marched rapidly to relieve Badajoz and almost defeated Beresford’s Anglo-Spanish-Portuguese army by again employing a flanking attack. The Spaniards, ably commanded by General Javier Castanos, held their own and a timely counterattack by the British Fusilier Brigade retrieved the situation, but losses on both sides were extremely heavy—8,000 (approximately 33%) for the French and 6,000 (approximately 18%) for the Allies, especially among the British (nearly 50%)—one of the heaviest loss rates of the Napoleonic wars. Badajoz, however, was resupplied and the British siege collapsed. Wellington never let Beresford command independently in combat again after this Pyrrhic victory.15

With these two battles, Wellington’s war in Spain gave way to a stalemate that centered on the two French-held fortresses of Badajoz and Ciudad Rodrigo. Whenever Wellington tried to invest these places, the French—Marmont and Soult—combined and confronted his forces, usually using the great bridge across the Tagus at Almaraz for lateral movement. Wellington resorted to a lengthy cat and mouse game for the rest of 1811, hoping for a French error. In the meantime, Napoleon continued to pull troops from Spain, weakening his forces further. By early 1812, as Napoleon was finalizing his invasion of Russia, Wellington struck. He first feinted toward Badajoz and then headed north and besieged Ciudad Rodrigo, assaulting and capturing it on 19 January. Then, moving swiftly against Badajoz, he placed it under siege for the third time since its capture by the French, famously assaulting it on the night of April 6–7, although his victory was sullied when his troops sacked the Spanish fortress in an orgy of looting, rape, and murder of the hapless Spanish inhabitants. These two coups put the lie to claims that Wellington was not capable of decisive, even rash, operational maneuvers.16

With his flanks thus secured, Wellington moved to ensure that Soult and Marmont could not come to each other’s aid once he advanced against one or the other in Spain. To accomplish this he sent his most trusted subordinate, General Rowland Hill, against the great bridge at Almaraz across the Tagus that connected Soult’s area of operations with that of Marmont. Hill put the garrison to flight and destroyed the bridge on May 19. Wellington now commenced offensive operations deep into Spain for the first time since 1809—just prior to Napoleon’s invasion of Russia. As usual he employed operational deception, tricking Soult into believing he intended to liberate Andalusia. Wellington reasoned that if he could defeat Marmont in central Spain, Andalusia must fall of its own accord. He advanced on interior lines to the north and attempted to lure Marmont’s army into a battle around Salamanca. However, Marmont proved almost as cautious as Wellington. The two spent most of the summer maneuvering against each other’s lines of communications in something of a throwback to 18th-century warfare (neither organized his army in corps, but rather left them in divisions for the duration of the campaign). Finally, on July 22 near the start point of the campaign at Salamanca, Marmont allowed the lead division of his army to become separated from his main body and Wellington pounced, destroying that division and scattered the next one behind it. He then repelled a vigorous French counterattack. Marmont was badly wounded and his army thrown into a disorganized retreat after losing almost 14,000 killed, wounded, and prisoners.17

This victory changed the landscape of the war in Spain. Soult was forced to evacuate southern Spain when Wellington liberated Madrid on August 12. Wellington overreached himself by attempting a lightning advance to seize Burgos in October. Unable to capture the city’s citadel and threatened by the superior French forces under Soult moving on his rear, Wellington conducted a strategic retreat back to his starting point at Ciudad Rodrigo. The French reentered Madrid, but they had traded the entirety of Southern Spain to regain it. By now December 1812 had arrived and Napoleon’s disaster in Russia made manifest, although its full import was not completely understood in Spain.18

From 1809 to 1812, Wellington had employed attrition warfare against the French, at one time dealing with the entire might of Napoleon’s empire. French errors notwithstanding, Wellington’s elegant mix of fortified compound warfare and protracted operations in the Peninsula exhausted French resources. French reinforcements seemed to arrive as worn and depleted as the troops they were supposed to support. This same phenomenon was now about to occur on a far larger scale in Russia. In contrast, Wellington’s creation of a viable Portuguese army gave him military echelons that the French ignored or underestimated as at Busaco. No longer was Spain an object to be conquered; it had become the base for an offensive threat to be defended against—and at the worst possible moment for the Emperor of the French.

NAPOLEONIC TOTAL WAR IN RUSSIA

The causes for the breakdown of the seemingly amicable relationship forged between Russia and the Napoleonic Empire at Tilsit are beyond the scope of this study. However, certainly Napoleon’s ruinous Continental System (see chapters 5 and 6) had done much to prepare the ground. By 1810, Russia was already preparing for war with Napoleon after Napoleon had offended the Tsar by occupying the Duchy of Oldenburg, which belonged to his sister’s husband. Napoleon’s policies vis-à-vis the Duchy of Warsaw and the potential political resurrection of Poland as a strong French ally further exacerbated relations between the two powers. Alexander even contemplated preemptively attacking the Duchy of Warsaw in the hope that the Prussians and Austrians might throw off the Napoleonic yoke and join him. Fortunately for Russia this did not happen. Instead, the Tsar’s emissaries signed the less than favorable Treaty of Bucharest in the long-running war with the Turks, thus freeing up distant armies for use against Napoleon prior to the French invasion in the summer of 1812.19

As the Napoleonic-Russian imperial relationship went from alliance, to neutrality, to hostility, Wellington’s campaign and use of the Lines of Torres Vedras gave thoughtful observers a recipe for the antidote to Napoleonic offensive power. Tsar Alexander watched these events unfold and commented to Napoleon’s ambassador Armand de Caulaincourt in 1811:

If the Emperor Napoleon makes war on me…it is possible, even probable, that we shall be defeated, assuming that we fight. But that will not mean that he can dictate a peace. The Spaniards have often been defeated; and they are not beaten, nor have they submitted. But they are not so far away from Paris as we are, and have neither our climate nor our resources to help them. We shall take no risks. We have plenty of room; and our standing army is well organized.20

If one equates the frozen forests and steppes of Russia to the British-dominated seas surrounding the Iberian Peninsula, the analogy is even closer to the example provided by Wellington and the Spanish. The solution to the Napoleonic method of the one-season, decisive campaign offered itself to both the Tsar and his minister of war General Michael Baron Barclay de Tolly—scorched-earth, mobilization on the largest possible scale, guerilla warfare, fighting retreats, inconclusive bloody battles, and no surrender. However, all of the elements of this strategy were not immediately adopted, even though the top leaders understood them as potential, even probable, courses of action.21

Throughout all of 1811 and the first part of 1812, the two sides built up their forces and prepared diplomatically for the expected “clash of the titans.” Napoleon’s preparations were on a gargantuan scale and by the spring of 1812 he had deployed over 449,000 troops in cantonments along the Vistula River in Poland.22 His alliance included the military forces of just about every dominion under his direct and indirect influence, including sizable contingents from both Austria and Prussia. Neither of these contingents can be categorized as “willing” and it is to Napoleon’s great discredit as a strategist and general that he had the bad judgment to place them on his northern and southern flanks to guard the advance of his central army group. The final break came effectively in April, when the Tsar presented Napoleon with an ultimatum to evacuate Prussia and return the Duchy of Oldenburg. This was tantamount to a declaration of war since it meant that Napoleon must also abandon the Grand Duchy of Warsaw. Adding injury to insult, the Tsar signed a treaty with Sweden, which freed further troops for use against Napoleon. Once Napoleon invaded, the Tsar’s representatives in Great Britain also signed a treaty of alliance with that nation, although British goods were already flowing into Russian ports. However, Russia would not lack for funds to help pay for the war.23

The plans and deployments of the French and Russians for this campaign reflect best, perhaps, the style of mobilization and operational components envisioned by the Soviet operational theorists like Isserson and Tukhachevsky 120 years later in the Soviet Union.24 Russia’s vast size seems to bring this sort of gigantic military effort out, no matter the age and the technological sophistication. We will turn first to Napoleon’s plans and deployments prior to the invasion. Napoleon cannot be faulted for failing to mobilize his vast resources. He even tried to broker a peace in Spain with Great Britain in order to simplify the task at hand, although this too-little, too-late initiative failed.25 Napoleon’s arrangements envisioned three strategic echelons in order to maintain the momentum of his offensive should he be drawn deeply into Russia, despite his hope that he could fix and defeat the Russian armies in Russian Poland and Lithuania. Napoleon’s first strategic echelon consisted of the bulk of the reconstituted Grande Armée, with the enlarged Imperial Guard (nearly 50,000) under his personal command. In addition were two armies commanded by his relatives, one under his step-son Prince Eugene Beauharnais, the Viceroy of Italy, and the other under his brother Jerome, King of Westphalia. These three armies constituted the central army group, also under Napoleon’s operational command, and might be considered the first army group of the modern era. This army group numbered 383,000 troops and 1,022 artillery pieces. Nearly half of this force was composed of nonnative French troops: Dutch, Swiss, Poles, Italians, Spanish, Portuguese, Croatians, and Germans from the Confederation of the Rhine. As mentioned, on Napoleon’s north and south flanks, respectively, were Marshal MacDonald’s X Corps (32,000 Prussians, Germans, and Poles with 84 guns) and Prince Karl zu Schwarzenberg’s Austrian corps (34,000 men with 60 guns).26

The second strategic echelon consisted of troops still forming up to be used as replacements for those in the first echelon. They consisted of about 165,000 soldiers, many of them in Marshal Victor’s IX Corps and included many Polish and German troops. The third strategic echelon amounted to about 60,000 troops and included the corps of Marshal Augereau, two of whose divisions were in the second echelon with Victor, as well as various garrisons in Poland. We might consider that a fourth strategic echelon existed in the remainder of the empire encompassing the National Guard, fortress garrisons and posts along the Atlantic coast (not including the Peninsula), the Danish Army and a virtual levée en masse for any French males not already serving between the ages of 20 and 26. These constituted something less than 275,000 men, but Napoleon was relying on further exactions from his allies—especially the Germans—and new troops to be raised in “liberated” areas of Russian Poland and Lithuania should he need troops for an unexpected crisis. Napoleon’s mobilization of these numbers could not be maintained for a protracted war, feeding and billeting them soon proved so daunting that they must either advance or demobilize—by May 1812 Napoleon had decided they would advance.27

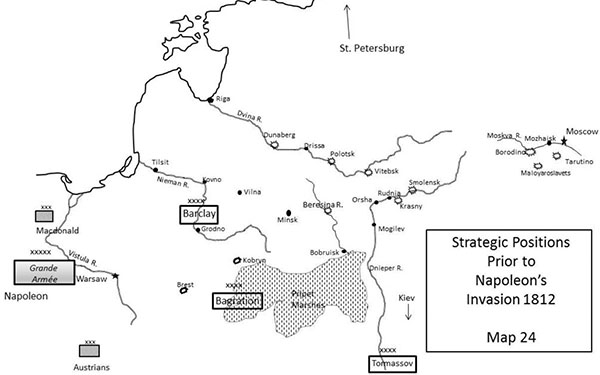

Napoleon’s plan was characteristically simple and based on reasonably good intelligence about the size and disposition of the two main Russian armies (discussed in the following). His goal was nothing less than the destruction of the bulk of Russian military power in Lithuania or at the very least west of Smolensk using his main army group. The larger Russian army (under Barclay de Tolly) numbered, according to his intelligence, around 125,000 troops as compared to a smaller army of 50,000 troops to its south (under Prince Bagration). The Emperor’s plan was to advance directly on the larger army, fix it, and destroy it. Despite having identified the location of the larger Russian field army prior to hostilities, successful execution of his plan required good intelligence about its position and movements once the campaign started. Napoleon simply decided to aim at the center of Barclay’s concentration of forces by marching on Vilna, the capital of Lithuania. A second assumption involved his being able to outmarch the main Russian army with at least enough of his troops to get it to stop and fight. Napoleon intended to improvise operationally as the situation dictated, hoping to conduct a massive maneuver against the flank and rear of Barclay’s army with either reserves from the main army or those under Eugene, the army on his immediate right. Finally, since the other two armies were positioned in echelon on his right flank, the Emperor planned for them to at least keep the more southerly Russian field force from joining with the main northern one. Once the destruction of the main Russian army was accomplished, Napoleon could turn to destroy the southern army, especially if Eugene or Jerome managed to find and fix it or slow it down, and then send out peace feelers to the Tsar. If these were rejected he could then bring up the second echelon and advance toward either St. Petersburg or Moscow. If all went well the campaign would be over in six weeks, somewhere in the vicinity of Vilna in Lithuania. If not, he could continue the campaign as necessary to a successful conclusion by the end of the summer or in early autumn before the first snows. Surely the Tsar would surrender if his armies were destroyed and one of his two capitals had been occupied? The willingness of the Tsar to surrender constituted Napoleon’s final assumption even though Caulaincourt had reported differently.28

Napoleon’s logistical preparations to support this plan made sense had the campaign turned out as he planned. Although his troops would be required to forage in some cases, he had large amounts of biscuit, grain, and mobile ovens created to support his armies. Also, his line of advance, and indeed his initial penetration into Russia at Kovno at the juncture of the Nieman and Vilia Rivers, was intended to take advantage of those two streams to support the main line of his advance to Vilna (see map 24). The weak link in the entire system of logistics, especially if the campaign did not develop along the nice, neat lines he hoped for, involved distributing the food to the immense army from river debarkation points and supply convoys. The means to do this involved using draught animals and these animals in turn needed as to be maintained and fed. Thus, a key problem might arise if the Russian army managed to escape to the east of Vilna without an engagement. Napoleon would be forced to choose between two options. The first required spending the precious weeks of good campaigning weather establishing a new line of logistical support using rivers and the Baltic toward St. Petersburg or, more likely, along the Dvina and Dnieper (Dnepr) rivers toward Smolensk. The second option would be to outstrip his logistical support by rapid marching of his troops on either line of Russian retreat in the hopes of catching them, while foraging as a stopgap measure. This last choice was risky, and Napoleon knew of it based on his previous experience in 1806–1807. Finally, the assumption of good weather during the Russian summer did not account for an extremely dry, hot continental summer. As we shall see, the extreme summer weather was to do more damage to Napoleon than either of the two Russian armies until the Emperor arrived before Borodino in August. Also, these circumstances applied somewhat to the Russian armies with the exception that they could forage far more effectively in their own territory than Napoleon and would be retreating onto their lines of magazines and depots, which permitted them to destroy what they did not eat or carry. Things would be immeasurably worse for Napoleon if the Russians employed a scorched-earth campaign along the route of their retreat as Wellington had in Portugal.29

Map 24 Strategic Positions Prior to Napoleon’s Invasion 1812

The Russians had a strong hand to play despite the nearly half million-man field army Napoleon had deployed for his campaign. They initially matched it with over 200,000 men in their first strategic echelon. As we have seen, they had two main field armies under Barclay de Tolly (hereafter Barclay: 127,000 men, 558 guns) and Prince Peter Bagration (48,000 men, 217 guns). There was a third army under General A. P. Tormassov (42,000 men, 164 guns) stationed south of the Pripet Marshes to protect Kiev and the southern invasion route of Russia.30 Alexander, based on his experiences in 1805–1807, had appointed Barclay minister of war in 1810 and adopted his scheme for mobilization that verged on the French idea of the levée en masse. These measures resulted in almost 800,000 men having been mobilized prior to Napoleon’s invasion, but, as seen, only 200,000 of these were trained and immediately to hand in June 1812. The rest were in the additional echelons available over the long term to the Tsar or stationed along Russia’s vast imperial borders. First, the Tsar’s diplomacy had freed up substantial forces from the Turkish and Swedish fronts: the Finnish Corps of General Steinheil (18,000 men, 72 guns) and the Army of the Danube under Admiral Tshitshagov (53,000 men, 240 guns). When added to other second echelon formations the total came to nearly 137,000 men, but most of these would not come into play for operational use until the late summer. Garrisons, depot battalions, and squadrons, Cossacks not yet called up, and some militia forces constituted a third strategic echelon of about 161,000 men, of which 133,000 eventually came into action against the French. Napoleon’s plan of mobilization theoretically could match (and overmatch) the arrival of these additional troops, but it is worth keeping in mind that almost 70,000 of these troops were veterans from Finland and the Danube and not second-class troops in any sense. Worse, Napoleon only learned of their availability after he had crossed the Nieman on June 24–25, 1812.31

From the beginning the Russians favored a Fabian strategy, avoiding direct engagement with Napoleon’s main army.32 To understand how the final plan came about, one must first understand the Imperial Russian army of that era. The shadow cast by Suvorov proved long and self-appointed candidates to succeed him were many. Also, Russian army leaders had played a key role in the assassination of the Tsar’s father Paul I, and this explains why the Tsar was unable to support Barclay as strongly as he might have once the campaign began. Barclay developed his plan principally from ideas that a Prussian named Ludwig Wolzogen advocated in 1810—demonstrating how early Russia had begun seriously considering war. Wolzogen’s plan involved a spoiling attack into Poland to devastate that area prior to Napoleon’s expected arrival and as a way to implement a “forward defense.” Wolzogen anticipated a fierce Napoleonic reaction and that Russian forces would then withdraw, bleeding off the strength of the French army with scorched-earth, guerillas, and a protracted fighting retreat as the Russian army withdrew into the vastness of Russia.33

By 1811 Wellington’s success in Portugal was well known, but the adoption of a purely defensive strategy posed dangers to the Tsar that could result in his own deposition or even assassination in favor of one of the many Grand Dukes. Alexander had to tread carefully. Nonetheless, most of his advisors favored a defensive posture, assuming the time for a preemptive offensive against Poland had passed. The Tsar was also greatly influenced by his personal military advisor Ernst von Phull, another Prussian general. Phull, who had served with Scharnhorst on the pre-1806 Prussian Quartermaster General Staff, envisioned creating a fortified camp à la Frederick the Great at Drissa (100 miles east of Vilna) that Barclay’s army might fall back on. From here the Russians might accept battle in a position of strength with a defensive line along the Dvina River and control access to the line of march to the south over the Beresina River to the Dnieper River. None of the Russian planners—Phull, Barclay, or Wolzogen—anticipated retreating any further east than this “three rivers” line.34 Additionally, Bagration’s southern army, reinforced to 80,000 troops, could operate per the Wolzogen-Barclay plan against the French flank and rear—or if Napoleon turned on Bagration, Barclay could do the same. In short, the Russians intended to open up the campaign with a shallow strategic withdrawal and a great defensive battle, or even a flank attack against an isolated Napoleonic force. Recall that this last component had been Bennigsen’s modus operandi during the Eylau-Friedland campaigns (see chapter 5), but now the Russians planned to use two armies instead of one to whittle down the French forces using attritional warfare. This optimistic plan fell apart once Bagration and Barclay realized the immense size of the forces facing them. Additionally, although Barclay was now 51 years old, he was younger than many more senior generals who resented his elevation over them. Worse, Barclay was not even Russian, but rather Livonian with some Scottish blood and a Baltic accent that was often regarded as “German”—the Russian euphemism for foreign officers. Bagration, too, was not Russian, but as a Georgian-Armenian regarded as more Russian than Barclay. Bagration also harbored an intense jealousy that Barclay had obtained the supreme command instead of him, one of Suvorov’s protégés. Finally, in the wings waited the disgraced recipients of former Napoleonic drubbings, Prince Mikhail Kutusov and Count Bennigsen, ready to take command if Barclay (still the minister of war) faltered.35

The size and geographic scope of the upcoming campaign presented a difficult command-and-control challenge for both sides. As we have seen, Napoleon created a new echelon, the army group, with himself in command, to help solve this problem. This would have been fine had Napoleon trusted his subordinates and allowed them more decision-making initiative at the operational level, what is called mission command in the U.S. Army (see chapter 4). However, other than Eugene (and not all historians agree on this point), Napoleon had done little to develop the habit of independent command in his subordinates. Some had demonstrated this talent earlier in their careers (Masséna) or as a result of accident and moral courage (Davout).36 Thus, although Napoleon created a de facto army group to help solve this situation, he had to command the army under his personal command, too (which was initially 222,000 men strong). Additionally, he treated Jerome, Eugene, Macdonald, and Schwarzenberg as he did the corps commanders under his direct control instead of trusting them (although perhaps he trusted Macdonald too much). Thus, he overburdened himself and his staff in trying to command and control at so many levels. Often his orders, if they arrived at all through the Cossack-infested country, arrived well after the situation had changed and only contributed to hesitation and confusion by his subordinates rather than adding value. The size of war had grown beyond the Emperor’s means to effectively control all its many parts, despite his computer-like brain and astonishing work ethic. He was older now and his capacity for work had atrophied as had his physical condition since 1809. Napoleon’s endurance had declined just as he began a campaign that would test him mentally and physically more than any other he had conducted.37

On the Russian side the problems tended toward the reverse—no one was in charge. This was largely Barclay’s doing due to his publication, as minister of war, of a new regulation governing the command of armies that gave Russian generals virtual autonomy.38 Alexander was nominally in command of everything at every level. Yet, instead of accompanying the army at all times, three weeks after the campaign started he departed the headquarters and generally remained behind the front lines, commanding at what might be called the political-military level, much as a U.S. president does today. However, he never appointed Barclay supreme commander and that officer had to use his position as war minister to try to direct Bagration. Although nominally under Barclay’s orders, Bagration often ignored them. Tormassov, Tshitshagov, and Steinheil took their marching orders directly from the Tsar. When the Tsar made recommendations, they were often just that. His commanders were more ready than most of Napoleon’s to make decisions based on the actual situation on the ground or in their sector and politely ignore operational guidance from the Tsar. Ironically, this loyal insubordination led to a far more effective system of command on the Russian side of the hill that more closely matches mission command than did Napoleon’s system.39

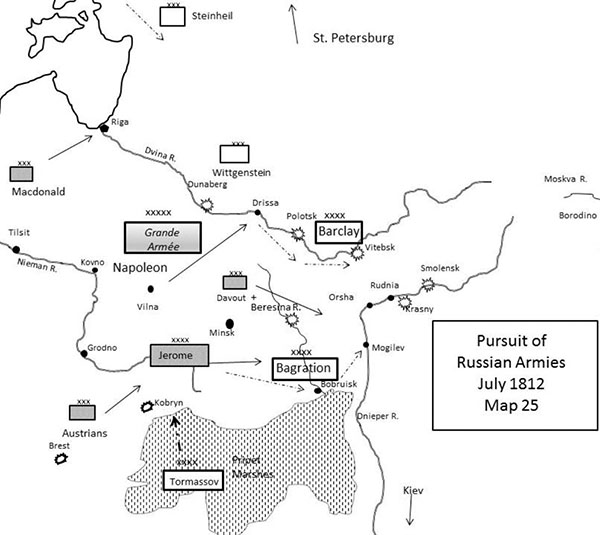

The first problem for Barclay and Bagration turned out to be one of timing. Napoleon thrust across the Niemen on June 24–25, getting over 120,000 troops across that river in two days, and advancing rapidly toward Vilna. The other units of his army crossed the river at other points, although both Jerome and Eugene were delayed by poor roads and lack of orders, respectively. Also, Bagration’s army was well short of the 80,000 troops envisaged by Phull’s plan and, worse, dangerously separated from Barclay. This separation exposed the Russian armies to defeat in detail. Because of the Drissa axis of retreat, they fell back on axes that diverged from each other with Davout’s extremely large I Corps (70,000 men) advancing between them. Murmuring soon arose among the native Russian generals as Barclay retreated without a major engagement toward Drissa. It soon became apparent that Drissa and several supporting fortifications (e.g., Dunaberg) were far from ready. No less an authority than Carl von Clausewitz, who had resigned his commission in the Prussian army and now served in the headquarters of Barclay’s army, assessed Drissa as follows: “if the Russians had not voluntarily abandoned this position, they would have been attacked…driven into the semi-circle of trenches and forced to capitulate.”40 Arriving at Drissa on July 8 ahead of the army, Barclay realized the position’s unsuitability. Accordingly, he made several excellent operational decisions. First, he detached the large corps of General Count Ludwig Wittgenstein (25,000) to operate independently northeast of the Dvina river line, protecting St. Petersburg and threatening the French flank. Secondly, he retreated to the southeast toward Vitebsk (July 18), correcting the error of the divergent axis with Bagration by moving toward that general’s line of retreat (see map 25).41

Map 25 Pursuit of Russian Armies July 1812

The retreat from Vilna by the First Army toward Drissa meant that Napoleon’s first blows hit relatively empty terrain, made emptier by the Russian scorched-earth policy and inhospitable due to roving Cossacks belonging to the Hetman Platov. Platov’s Cossack Corps had the job of both covering the retreat and linking the armies of Barclay and Bagration. In the upcoming weeks, these nimble Cossacks, sometimes supported by regular Russian cavalry, usually bested their French counterparts in the numerous cavalry skirmishes of the campaign. Unable to catch Barclay at Vilna, Napoleon adopted the second course of action mentioned before; he decided to risk outstripping his plodding supply trains (and boats) and press on.42

The vulnerability of Bagration’s Second Army now attracted the Emperor’s primary attention as he sent Davout south to cooperate with Jerome in trying to destroy it. However, Jerome moved slowly and assumed Davout was under his command in this ad hoc army group, not Napoleon’s. Further, Davout had almost as far to march to reach Bagration as the Russian did to escape him. Finally, the confusion of command and ignorance about Bagration’s anticipated line of retreat resulted in Davout failing to trap Bagration, although this maneuver temporarily prevented Bagration’s juncture with Barclay. Napoleon exploded in wrath against his younger brother, sending a letter so insulting that when Jerome received it on July 14 he turned over his command to his chief of staff and promptly returned to Westphalia three days later, taking his Westphalian Royal Guard with him. Ironically this was the same day that Barclay began his southeastward movement away from Drissa toward Bagration.43

Napoleon’s huge army found itself spread across almost 300 miles of frontage from Riga to the northern edge of the Pripet Marshes. His lumbering juggernaut also suffered immensely from straggling and the heat of the Russian summer. Poorly cared-for soldiers and animals littered the crude roads of Lithuania, Poland, and White Russia (Byelorussia). Cossacks and peasants alike (once in Russia) murdered or took them prisoner, usually the former. Water, food, and rest were all in short supply. The wastage of draught animals and horses in the first two weeks of the campaign was beyond anything anticipated by Napoleon and was made worse by the failure of the French cavalry to maintain a good picture of Russian movements. His cavalry included many new horsemen who had very little training on the care and feeding of horses, further decimating the mounts of the cavalry.44 Additionally, unseasonable heavy rains now began to alternate with the heat and combined to make more men, horses, and oxen sick and further slowed movement by turning the roads to mud. Horses foraged not on prepared fodder (oats and barley) but on the unripe crops of this season, which added digestive ailments to the other causes of death. Around 10,000 dead horses alone littered the roads to Vilna, causing Napoleon to leave 80 guns there for lack of transport. The Russian summer of 1812 is not given its due in many histories of this campaign, but its impact in the opening months was as significant as the effects of the more famous winter later that year.45

Bagration, in the meantime, regarded himself as sorely used by his “non-Russian” nominal superior in command. As Barclay withdrew toward Drissa, the Tsar had dispatched orders for Bagration to come north to unite with First Army. This Bagration had done, running into the advancing French and then turning south again; deciding he could not break through the entire French army, which he believed was at Minsk. He blamed all his misfortunes on Barclay, believing that Napoleon himself had come south with his entire army to destroy him personally (Napoleon had remained in Vilna). Despite his bravado and accusations of treason against Barclay, he wisely decided to retreat due east through Bobruisk, turning north to join Barclay at Vitebsk by way of Mogilev.46

Barclay, now in sole command of the First Army after the Tsar’s departure, hoped to unite with Bagration near Vitebsk and there fight the battle the Russian generals and the Tsar clamored for. Responding to his understanding of the situation, Napoleon left Davout in charge of the pursuit of Bagration and concentrated the bulk of the Grande Armée under himself. However, in doing so he made another significant detachment from his forces. The Saxon Corps (VII) under General Reynier moved south to protect his strategic rear in Poland from Tormassov’s army. Napoleon now tried to correct the mistake he had made in putting Schwarzenberg’s Austrians on the far right flank, ordering them to come north and join the army group in the center.47 On the northern flank Napoleon had committed himself to a grand operational maneuver that has become known to history as “the maneuver on Vitebsk.”48 His goal was to use the forces on his left (northern) flank to engage Barclay on the right bank of the Dvina while he took the main army to Vitebsk and cut off the Russians from both Smolensk and Bagration. The problem with this plan was that it was implemented without accurate knowledge of where Barclay actually was and relied heavily on Murat’s cavalry reserve to cause the First Army to slow down and fight rearguard actions. The only actions being fought were between the two cavalry forces, with Murat often bested and the Russian guns and infantry reaching Vitebsk before Napoleon. After arriving at Vitebsk, Barclay came close to making an error in bowing to the will of the Russian hotheads the Tsar had left behind and fighting a battle. However, circumstances conspired to allow the Russians to escape as Barclay waited for Doctorov’s Corps and Pahlen’s cavalry to rejoin the First Army for the battle. To cover these troops’ arrival, Barclay ordered his rearguard to fight delaying actions all day (July 25) in advance of his position with other detached troops. After Doctorov and Pahlen arrived, Barclay received Bagration’s message that he had been blocked by Davout from coming north near Mogilev on July 23. Bagration was much criticized for not plowing through Davout, which he outnumbered 2–1, but his decision proved fortuitous. This news convinced Barclay to withdraw and this decision in turn denied Napoleon his best opportunity to destroy one of the Russian armies before they united. By July 27, Napoleon had gathered more than 135,000 troops versus Barclay’s 75,000—a French victory was almost certain had Barclay stayed put.49

Nonetheless, on July 26–27, Barclay’s rearguard again fought aggressive rearguard actions to trick Napoleon about his intentions and then made good his escape to Smolensk, arriving there on August 2. Bagration arrived the following day, having countermarched down the Dnieper and crossed that river before pushing northeast to Smolensk. Napoleon’s attempt to keep the Russian armies separated had failed, although some historians claim he let them unite in order to destroy them at one blow, giving him a prescience he did not have. At any rate, after his army group’s three exhausting maneuvers on Vilna, Drissa, and now Vitebsk, Napoleon called a halt to the pursuit and gave his troops a rare week-long operational pause. He even considered, briefly, ending the campaign for that year.50 Napoleon, despite his first campaign in Italy and the experience of Spain, did not believe in protracted war. As he told his marshals, “Nothing is more dangerous to us than a prolonged war.”51 Historian Richard Riehn captured a reasonable operational explanation for why Napoleon continued a campaign that had already seen one-fourth of his first echelon army group melt away to desertion, disease, and exhaustion:

Despite the cost of the campaign so far, it still had not occurred to him that his method of campaigning was out of place in this theater of war and that it was…the most important source of his losses. Yet given the…expanses of Russia…[and] the means of communication, success, if it was to be had at all, could come only through a systematic conduct of the war. Just as the exploitation of [Russia’s] resources would require much time…so would the securing of these require a step-by-step advance, establishing new operations bases because no territory could be left behind with its resources not secured. This kind of warfare…was totally alien to Napoleon’s style.52 [emphasis added]

Napoleon the operational artist did not adjust to the imperatives of a protracted campaign as he had done earlier in his career in both Italy and Poland, relying instead on an Austerlitz or Wagram masterstroke to solve all his strategic problems. When that stroke did not materialize he seems to have simply “doubled down” to try and press on for another roll of the dice and a decisive battle. He no longer took risks, rather he began to gamble with the very success of the entire war.

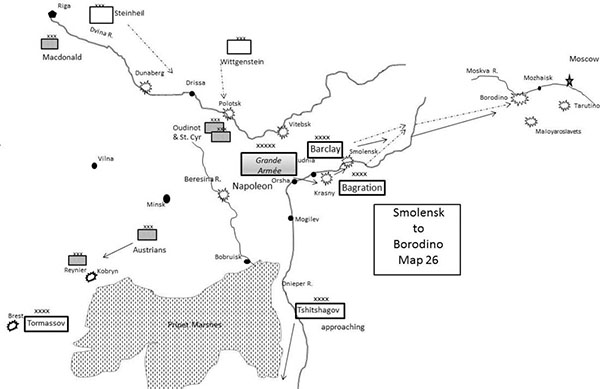

Worse, as Napoleon rested his troops at Vitebsk, trouble developed on his flanks. In the south his attempt to have Reynier’s small corps of 17,000 Saxons protect Poland from Tormassov’s army of over 40,000 received a rude shock when Tormassov seized Brest and then destroyed one of Reynier’s brigades at Kobryn on July 27 (see map 26). If Tormassov had acted more aggressively he might have bagged Reynier’s entire corps; as it was, Reynier retreated and sent out a message for help to Prince Schwarzenberg, who turned around with his strong Austrian corps of 30,000 to support him. Napoleon now directed Schwarzenberg to take command of both corps. In the north Marshal Oudinot crossed the Dvina to attack Wittgenstein north of Polotsk. Wittgenstein performed his role as an operational economy of force to perfection. He first reinforced his corps with the garrison of Dunaberg, abandoning that fortress, and then bested Oudinot in a series of actions in late July and early August. By August 2 Oudinot was back in Polotsk, requesting that Napoleon send him reinforcements to keep Wittgenstein at bay. Napoleon sent the weakened Bavarian Corps (13,000 men) to help. It was commanded by General Gouvion St. Cyr, one of the few generals in Napoleon’s army capable of independent command, but St. Cyr, for the moment, remained subordinate to the hapless Oudinot.53

Map 26 Smolensk to Borodino

These actions now allow us to compare the use and efficacy of both sides’ operational reserves for the first five weeks of the campaign. In Napoleon’s case his secondary operational echelon had been whittled down by three entire corps to deal with Russian flanking forces. Barclay detached one corps but Napoleon had to eventually detach two to account for it (not including Macdonald). Worse, Wittgenstein won several actions, further increasing Russian morale and momentum and demoralizing the French. On the southern flank, Napoleon had attempted to bring up Schwarzenberg’s strong and relatively healthy Austrian corps for use as a fresh operational echelon. Instead, because he left too weak a force (Reynier) to cover his lines of communication in Poland, Napoleon was forced to send this corps back.

As for the Russians, they had suffered grievously too, but not as badly as the French, losing 30,000 troops to all causes as compared with over 100,000 for Napoleon. While Napoleon’s reserves struggled to catch up or were detached to deal with crises on the flanks, the Russians collapsed on their own lines of communication, integrating 20,000 reserve troops as they retreated. While the Russians fell back on fresh reserves waiting at well-stocked depots, the French replacements and reserves made exhausting marches in the hot sun to catch up with the leading elements of Napoleon’s always-advancing army group. Finally, the Russians proved, as they had in Italy in 1799, that they could keep pace with, and even outmarch, the French infantry. Because their forces were smaller and more disciplined they lost fewer stragglers and often marched at night to avoid the heat of the day. Further, Alexander had ordered the mobilization of militia after returning to Moscow and then directed another round of conscription in mid-August. Fresh, albeit raw and untrained, troops would join the Russian army in growing numbers the longer the campaign proceeded.54 Napoleon’s margin of superiority grew more slender with each kilometer that he advanced, despite the immense resources and care he had taken to ensure that on the day of battle his superiority would be decisive.

Bagration, after a cordial meeting with Barclay, had agreed to subordinate himself to Barclay, but he had also animated the latter with his bellicose spirit. Barclay yielded and decided to attempt an offensive—a spoiling attack much like Wittgenstein’s—against Napoleon’s forces advancing lethargically (according to Russian intelligence) from Vitebsk. This idea was founded on the notion that Napoleon was far weaker than he actually was and had been buttressed by the news of the successes on the French flanks.55 In reality, Napoleon’s main army group approached 190,000 men while Barclay and Bagration had a little over 120,000. The Russians were about to offer Napoleon what he most craved—a large battle.56 Napoleon’s plan remained the same, to hold on his left and attempt to march around the Russian left flank and rear at Smolensk. To do this he would have to march farther than if he advanced directly toward Smolensk from Vitebsk. Clausewitz wrote of this decision, “It is inconceivable how Bonaparte omitted to throw forward his right wing, so as to cut off the Russians from [the direct road through Rudnia].” In hindsight, Clausewitz was right; had Napoleon gone straight at his objective, the united Russian army, he would almost certainly have engaged it in a significant meeting engagement north and west of the Dnieper, although whether he would have destroyed it is open to debate.57 Both forces hit relatively empty terrain, like two blind boxers, although Barclay’s advance guard surprised and defeated a French cavalry division near Inkovo on August 8. This action caused Napoleon to move aggressively against Smolensk. As the Russians advanced north of the Dnieper west of Smolensk, Napoleon’s main body swung around near Orsha and crossed the great west to south bend in the Dnieper River. However, Barclay’s stop-and-start offensive halted for good on August 12, when, in Clausewitz’s quaint phrase, “he became anxious about his retreat.”58

Napoleon’s advance guard under Murat—three cavalry corps numbering almost 15,000 troopers—arrived at Krasny on August 14, where the dilatory Bagration, operating on Barclay’s left, had placed a division under General Neverovsky. The Russians were hustled out of Krasny, fighting desperately against Murat as they withdrew in a divisional square toward Smolensk. Fortunately, the slow speed of Bagration’s advance, in part due to his concern over the open left flank at Smolensk, allowed him to throw General Raievsky’s nearby corps (17,000) into Smolensk, preventing Murat and his supporting infantry from capturing it outright on the following day. The result was a confusing series of battles around Smolensk. Neverovsky notified the “anxious” Barclay of his misfortune on August 15 and that was all that was needed for Barclay to make his decision to continue the retreat. Thus it was that the two character flaws in the main Russian generals, irresolution for Barclay and insubordination for Bagration, combined serendipitously to save the Russian army, although much bloody fighting had to be done to do it. Napoleon fought an indecisive series of battles from August 15–19 around Smolensk. Pummeled in the early days of these engagements, Bagration’s army escaped to the east on August 17, Barclay, fighting several stiff rearguard actions under very trying circumstances, followed on August 19. Clausewitz dryly noted that each side lost around “20,000 men” although he includes the number from Krasny in his totals. Smolensk, proud city of Old Russia, lay in smoldering ruins.59

Barclay’s actions from August 3–20, through luck, occasional resolve, and “anxiety,” saved the Russian army, but it doomed his position as the de facto commander of the Russian army group. Russian generals and favorites of the Tsar, who felt he had denied them a wonderful victory, convinced Alexander to dismiss Barclay from command. As the battles around Smolensk raged, the Tsar reluctantly convened a committee to pick a replacement for Barclay as supreme commander on August 17. Prince Kutusov got the nod as commander with the scheming regicide Count Bennigsen as his chief of staff. Barclay, instead of being drummed from the army, was demoted back into his original operational billet as commander of the First Army. Kutusov joined the army as Barclay continued to withdraw toward Moscow on August 29. Kutusov faced a tricky situation since, like Barclay, his inclination was to continue to withdraw. However, the Tsar and most of the Russian army expected him to halt and fight Napoleon. Kutusov knew that if he did not fight the back-stabbing Bennigsen might take his place.60

As the Russian army had withdrawn, it absorbed another corps of replacements under General Mikhail Miloradovitch, nearly making up the army’s losses at Smolensk. Napoleon was not so fortunate, although on his flanks both Schwarzenberg and St. Cyr (who took command on August 17 from the wounded Oudinot) had won victories that removed, for the time being, the threats to his rear. These victories, as it turned out, gave Napoleon a false sense of security about his strategic flanks. Napoleon’s main army group was now down by 20,000 and by the time he reached Borodino his margin of superiority over the Russians had dropped to approximately 134,000 troops versus 120,000 Russians. However, 10,000 of the Russians were the recently mobilized militia, many armed only with pikes. Napoleon’s greatest fear was that the Russian army would deny him a battle and again retreat, but Kutusov did not disappoint him.61

The first elements of the French advance guard arrived near the little town of Borodino just west of the confluence of the Kalatsha and Moskva (Moscow) Rivers on September 5, fighting a stiff battle against Bagration’s rearguard. All this did was to subtract another 4,000 troops from each side. Napoleon then brought up the rest of his army on September 6 and on the following day the holocaust of Borodino occurred. Only the sea battle of Lepanto (1571) exceeded this bloodletting in terms of a single day’s slaughter until the disastrous first day of the Somme in 1916. Some accounts list a combined casualty count of over 100,000 with as many as 40,000 killed, although a total of 80,000 casualties for the two armies is probably closest, with the Russians losing almost twice as many as the French. Most were lost to mass artillery fire, with 587 guns on the French side and 624 on the Russian, spitting canister and round shot nonstop for most of the day.62 It was the first battle where two army groups organized as such fought head to head.

Ironically, Kutusov had left the actual conduct of the battle to Barclay, Bagration, and Platov, his principal subordinate commanders. Its final phases were almost entirely under Barclay’s tactical control after Bagration was mortally wounded. By the time the fighting ended at 4:00 p.m. it was Barclay who stabilized the front, keeping the mauled Russian army on the field. After the battle, Barclay was cheered by the troops wherever he went. Kutusov, meanwhile, sent a message to the Tsar declaring victory and went to bed. He was roused in the middle of the night by reports of the loss of almost half the army and he gave orders to pull back several miles to Mozhaisk. The French army, also badly damaged, withdrew in some places for the night, convinced of a victory, and then apparently confirmed as much the next morning when it found the Russians retreating in three columns. Murat asked Napoleon to release the Imperial Guard cavalry for a pursuit but he was denied permission. Napoleon has been much criticized (although, oddly, not by Clausewitz) for his failure to release his last tactical and operational reserves both on the day of battle and afterward to seal his victory.63

Borodino solved little for either side. Kutusov had fought the battle everyone had clamored for, lost half the army, and now his goal was to save the other half. He continued his retreat, abandoning 10,000 wounded in Mozhaisk, while boldly proclaiming his plan to fight another battle before Moscow, but this was designed to obscure his real intent. When a council of war (including Bennigsen) recommended another battle, he ignored them, making his most important command decision of the campaign and leaving Moscow to the Grande Armée. Clausewitz implied that this was the most important Russian operational decision of the war. Credit for the eventual victory, which was not so clear at the time, goes to both Barclay and Kutusov: the former preserved the army at Borodino and the latter preserved it afterward.64

THE RETREAT

Napoleon now made his final disastrous error of the campaign. Instead of making the Russian army his objective, as he had so often in his career, he settled for the occupation of Moscow, holding it hostage in anticipation of a negotiated peace. Kutusov retreated to the southwest of Moscow, just out of reach of the French in unforaged countryside undamaged by war. This location allowed him, in Clausewitz’s phrase, to “play hide-and-seek” in the vast expanses of Russia should Napoleon come after him.65 It was also nearer to the armies of Tshitshagov and Tormassov. Napoleon had passed the “culminating point of victory,” but it took five weeks of intolerable indecision as Moscow burned around him to recognize this fact. It was at this point that Napoleon’s decisions no longer influenced the issue of retreat; it was foreordained when the Tsar refused all emissary attempts in St. Petersburg. The issue now to be decided was the scale of the disaster and Napoleon’s long halt in Moscow during the last good weather of the year ensured it would be catastrophic.66

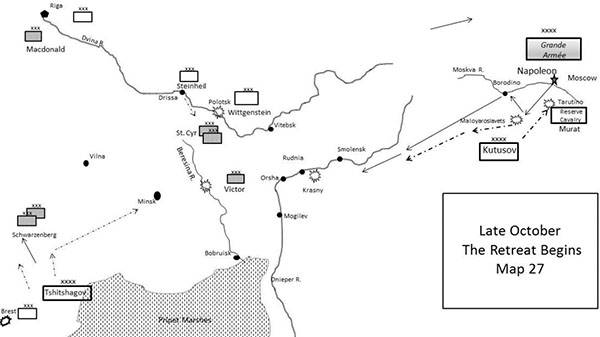

The remainder of the campaign has often been identified as the cause of Napoleon’s defeat: a long retreat through the bitter winter that destroyed the Grande Armée. In contrast, the evidence presented suggests that army was already defeated when it marched into Moscow and doomed as it marched out. Kutuzov’s army slowly increased in size until it outnumbered Napoleon’s—by October it numbered approximately 100,000 troops. Napoleon’s operational reserves were strung out on his flanks and lines of communication and his army got no stronger as it sat idly in Moscow. Napoleon received nothing but bad news from his flanks, and despite making St. Cyr a marshal after that general’s victory at Polotsk (August 18) against Wittgenstein, the arrival of Steinheil’s Finnish Corps in combination with Wittgenstein caused the wounded St. Cyr to retreat. In the south, Tshitshagov, now in overall command, sidestepped Schwarzenberg and began advancing north against Napoleon’s lines of communication. Kutusov contented himself with bringing Tormassov up from the south to replace Bagration (who had died of his wounds) and waited on events. Sensing the time was right, he surprised Murat’s covering force south of Moscow at Tarutino on October 18 (see map 27). Murat lost nearly 4,000 men and 36 guns. This defeat convinced Napoleon to retreat and Moscow was evacuated on October 19 in relatively good weather. The Grande Armée numbered no more than 95,000 troops.67

Map 27 Late October The Retreat Begins

Napoleon’s intent was to do what the Russians had done and incorporate his reserves as he retreated and then to winter in Smolensk if circumstances permitted it. His route of march to the southwest through relatively unravaged Russian countryside had much to recommend it and might get him to Smolensk, if all went well, by early November. Autumn rains slowed him down and on October 24 at Maloyaroslavets the advance guard of his army under Eugene collided with Kutuzov’s main army, giving both forces a rude shock. Napoleon, not realizing that Kutusov had pulled back and opened the escape route west, countermarched, losing another week of reasonably good weather, and retreated to the more northerly Moscow-Smolensk road, scene of so much death and misery that summer. Winter arrived as the first snows fell on October 31. Kutusov marched parallel to the French line of retreat, harrying their every step with Cossacks. Without the glue of promised victory, Napoleon’s army began to dissolve. His army was in such bad condition by the time it arrived in Smolensk (November 9) that it had fewer than 30,000 effectives and another 20,000 stragglers. Worse, Kutusov cut his line of retreat at Krasny and Napoleon was forced to use his Imperial Guard on November 16 to cut his way through. Marshal Ney’s corps, bringing up the rear was cut off. Ney, retreating north and then south again, managed to bring a pitiful 900 men back into the army, but Krasny was a major disaster. In addition to 6,000 casualties, some 26,000 French stragglers were captured.68

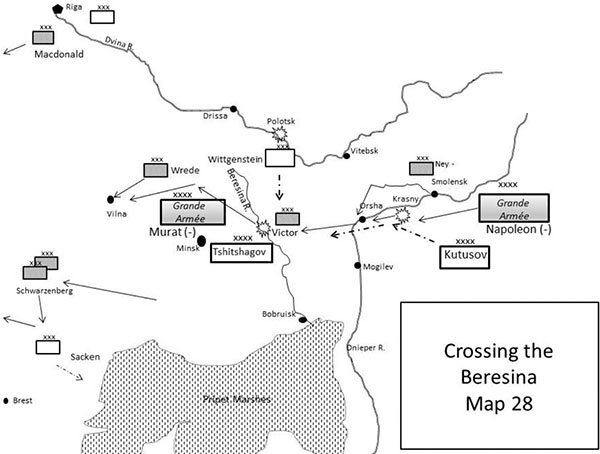

Where were Napoleon’s operational reserves, including the supposedly fresh corps of Victor? These forces were fighting for their lives and also retreating. Wittgenstein and Tshitshagov advanced from the north and south, respectively, toward the Beresina River to cut off Napoleon’s retreat (see map 28). Here a brief flash of Napoleonic brilliance occurred as he defeated Tshitshagov and bluffed Wittgenstein from 25 to 29 November. Kutusov, now seriously ill (he would die in the spring of 1813), hung back with the main army, satisfied to let Napoleon leave Russia without risking a defeat. Victor’s still-intact corps and Oudinot’s bloodied one united with the main army and did most of the fighting. However, as at Krasny, once the disciplined core of what was left of Napoleon’s “army group” crossed the Beresina, tens of thousands of stragglers were cut off and fell into enemy hands. According to Clausewitz: “Chance certainly somewhat favored Bonaparte…but it was his reputation which chiefly saved him, and he traded in this instance on a capital amassed long before.”69 Some accounts list as many as 30,000 stragglers—no longer fighting but struggling to avoid dying of starvation, exposure, or both—falling into Russian hands. David Chandler estimated the losses as coming to perhaps 50,000 to 60,000, including many who drowned or froze in the frigid river. Napoleon stayed with the army until December 5 and then departed at Smorgoni for Paris to quell conspiracies, propagate the myth that the Russian winter had defeated him, and prepare for the worst, turning over what was left to Murat.70

Map 28 Crossing the Beresina

* * *

Napoleon’s army, including replacements near Vilna, lost another 40,000 to 50,000 troops as it withdrew from Russia—many of them second and third echelon replacements who succumbed to the bitter cold and died or were captured. Of the 66,000 troops that remained in Poland by mid-December, nearly 43,000 were Austrians and Prussians who soon deserted Napoleon (see chapter 8). He now fell back on what might be metaphorically termed his strategic seed corn. The cadre of surviving French soldiers, probably no more than 2,000 of them officers, formed the nucleus for Napoleon’s armies of 1813, but he had sacrificed his strategic reserves in Russia and the rest remained tied down in Spain in a war they had already lost. His cavalry would never recover from its Russian losses and he lost more artillery in this campaign than any general in history. The campaign had also seriously damaged the Russians, Kutusov would soon die and the army fell into the hands of Wittgenstein. While Napoleon probably lost over half a million men in Russia, the Tsar’s legions suffered nearly a quarter million losses. Alexander’s protracted war of attrition had ejected the conqueror from his nation and circumstances soon made it possible for him to continue hostilities into Germany.71 We leave the last word to Clausewitz, who spent the majority of the campaign in the headquarters of the main Russian army:

Bonaparte determined to conduct and terminate the war in Russia as he had so many others. To begin with decisive battles, and to profit by their advantages…to go on playing double or quits till he broke the bank…In Spain it had failed…. It is extraordinary, and perhaps the greatest error he ever committed, that he did not visit the Peninsula in person…. He reached Moscow with 90,000 men, he should have reached it with 200,000. This would have been possible if he had handled his army with more care and forbearance.72